Home to Limuw

A 50-year odyssey.

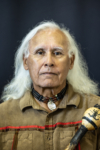

Words by Alan Salazar “Puchuk Ya’ia’c” as told to Jeff McElroy

After paddling for 10 hours, we were still over 2 miles from our landing spot on Santa Cruz Island, nearly 30 miles off the coast of California. The tomol was taking on lots of water. There was a 30-minute period of paddling where we did not move forward. Only when we dug deep and paddled against the current as hard as we could did we make progress. That’s when I realized what great seamen my ancestors were. It’s what we strive for today, to be strong, brave and knowledgeable, like my Chumash ancestors.

We are and have been a maritime culture for over 13,000 years. Our territory starts on California’s Central Coast, around Morro Bay, and stretches south to Malibu. Over 170 miles of prime ocean coastline, plus the Channel Islands—Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa and San Miguel—are Chumash territory. We have been master canoe builders for thousands of years, but it is our ocean plank tomols that we are famous for.

I was not raised on the water. I was born in 1951 in the city of San Fernando in Los Angeles County, and my journey home to the coast took almost a lifetime. My father, a US Marine with Tataviam and Chumash bloodlines, was adamant that my three siblings and I identify as Indians (the term used then) and that it would say “Indian” on our birth certificates. We moved farther inland to the Central Valley, where my parents were one of the few interracial couples, and by age 6, I knew when a person was staring or glaring at me because of the color of my skin.

During the summer of 1957, my older brother and I asked my dad if we could get mohawk haircuts because the Mohawks were the only Indians we saw on TV, fierce warriors, all. I still have the photo of us Salazar boys standing in front of the barbershop on Main Street with mohawk haircuts; Pop, too. He told us, “Don’t go looking for a fight, but don’t run from one, either. Stand up for what you believe.” That’s the way I was raised, and you could say that’s Native pride.

We settled in Bakersfield when I was a teenager, where I would stay for most of my adult life. It’s where I got married, raised a family and worked as a plasterer and juvenile institution officer. I grew up with folks straight out of The Grapes of Wrath, emigrants from Oklahoma who had come to California during the Dust Bowl, many of them settling in Bakersfield. This migration also included folks with Choctaw, Cherokee and Chickasaw ancestry. In my 30s, I started getting more actively involved with the Native population and several Native organizations, including the Indian Health Service.

For our family vacations, we escaped the heat of Bakersfield and stayed by the sea in Ventura. Every time we made the drive down the grade on Interstate 5 and bottomed out at State Highway 126, by Six Flags Magic Mountain, I felt something strange in the core of my stomach. I couldn’t explain it until, 20 years later, I began researching my family history with anthropologist Dr. John Johnson. He accessed records from mission San Fernando and pinpointed my ancestry to two villages: Tapu on the Chumash side (Tapo Canyon in Simi Valley) and Chaguayanga on the Tataviam side (Castaic, by the I-5/126 interchange). That tingle in my stomach, all along, had been the feeling of coming home.

The word Tšumaš (Chumash) is derived from the term ’ałtšum (shell bead money) and is a name for people inhabiting Mitšumaš (a previous name for Santa Cruz Island that means “place of the makers of shell bead money“). Today, Chumash call the island Limuw. The other islands are known as ʔanyapax (Anacapa), Wima (Santa Rosa) and Tuqan (San Miguel). Photo: Gary Kavanagh

At the end of the last Ice Age roughly 10,000 years ago, melting glaciers warmed the ocean and the sea level rose about 400 feet, moving the coastline miles farther back than it once was. There was one large island, Santarosae, that became the Channel Islands we see today from Ventura and Santa Barbara. Prior to the sea level rise, Santarosae Island was only about 4 miles off the coast in some places, a trip easily made in a small tule reed canoe, similar to a modern kayak. After the rise, the distance increased, and the currents became stronger. My theory, based on research from Chumash Elders, historians, anthropologists and canoe people, is that the Chumash started building larger plank tomols about 7,000 years ago. They needed larger, stronger vessels to transport people from mainland villages to island villages and support fishing for larger catch, like sharks and swordfish.

Our tomol builders (tomoleros, as the Spanish would later call them) were highly skilled craftsmen and respected tribal members. They collected large driftwood logs that washed up on shore after big storms; redwood trees from Northern California and Oregon were preferred for their strength. Then, they split the logs by shaping whale-bone ribs into wedges and hammering them into the logs with hammerstones. The splitting of the logs allowed them to make long boards, similar to modern 2-by-6 or 2-by-8 planks, which they sanded with shark skin and cut to lengths between 8 to 20 feet.

The bottom board was usually the longest and thickest; the shorter boards formed the walls. The tomol builders glued the boards together with a mixture called yop—hard tar or asphalt melted with pine pitch or pine sap. This tar is still found throughout Southern California today in natural seeps. After the tar set, they tied the boards together with twine made from plant fibers such as dogbane; it took a tremendous amount of twine to build one tomol.

Starting in 1769, Chumash people were enslaved and forced to labor in the Catholic missions. As young Chumash men and women became blacksmiths, ranch hands, cooks and maids, our traditional ecological knowledge, tomol knowledge included, was not being passed from generation to generation. After the 1850s, we had stopped building our plank tomols.

Left: Tsqap’ihew (pelican feather), xapšƏx (white sage) and qašƏ (red abalone) are sacred elements of Chumash prayers and blessings. Photo: Tim Davis

Right: “Saying prayers and making offerings is done at every tomol practice and crossing,” Alan Salazar says. “Blessing everything, even the paddles, is important.” Photo: Tim Davis

In 1995, a few years after my divorce, I decided to move to Ventura to find work and connect more with my Chumash community. A year later, members of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History and the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum approached me to lead a grant project to build three tomols. As one of the founding members of the newly formed Chumash Maritime Association, I raised the museums’s proposal during our first few meetings, and we decided to move forward with the project. Out of respect for my Chumash community members, many of whom grew up on their ancestral lands around the Santa Barbara area, I chose to join the project but not lead it.

In 1997, I joined a small group of Chumash people and supporters of the Chumash to build ‘Elye’wun, which means swordfish. I had the honor of being in the first crew when we put her in the water at Santa Barbara Harbor. For the next four years, our group practiced paddling on flat water and along the coast, learning how to row as a team with our 11-foot paddles and how many sandbags to place in the bottom of the boat to stabilize it. In September 2001, we believed we were ready to cross the channel from Channel Islands Harbor to Santa Cruz Island, the island the Chumash call Limuw.

We left at 3:45 a.m. on September 8, 2001. I was in the first spot of the tomol with three paddlers behind me and our captain. We’d never paddled in the dark, something my Chumash ancestors had experienced thousands of times. Paddling with the stars overhead was a spiritual awakening for many of us, and from that morning on, we started calling the first crew “dark water paddlers.”

It took us over 11 hours to cross the channel that day. The currents and headwind were stronger than we’d imagined, and the tomol took on 10 inches of water. We made the decision to move one of our paddlers and six sandbags to the support boat. It lightened ‘Elye’wun enough for us to make the last few miles safely. We were greeted by friends, family and supporters that evening on Limuw, our homeland, and celebrated the first Chumash-powered crossing in over 150 years.

Left: “For the last 12 years, I have paddled in the Santa Ynez Chumash tomol, Muptami (Ancient Dreams),” Salazar says. “We’ve always used abalone inlay on the ears of the tomols to honor the sun, meteor showers, star constellations and animal spirits.” Photo: Tim Davis

Right: “Our tomols are very deep, over 2 feet from the top board to the bottom,” Salazar says. “We paddle on our knees to be high enough to reach over the sides. Our paddles are double-bladed and over 11 feet long. It takes great strength, balance and endurance to paddle a tomol.” Photo: Tim Davis