Abstract

Brain computation is metabolically expensive and requires the supply of significant amounts of energy. Mitochondria are highly specialized organelles whose main function is to generate cellular energy. Due to their complex morphologies, neurons are especially dependent on a set of tools necessary to regulate mitochondrial function locally in order to match energy provision with local demands. By regulating mitochondrial transport, neurons control the local availability of mitochondrial mass in response to changes in synaptic activity. Neurons also modulate mitochondrial dynamics locally to adjust metabolic efficiency with energetic demand. Additionally, neurons remove inefficient mitochondria through mitophagy. Neurons coordinate these processes through signalling pathways that couple energetic expenditure with energy availability. When these mechanisms fail, neurons can no longer support brain function giving rise to neuropathological states like metabolic syndromes or neurodegeneration.

Introduction

Brain information processing requires the constant provision of high levels of energy [1], much of which is consumed to restore the ion movements that underlie neuronal communication and the re-uptake of neurotransmitters [2]. Indeed, organisms have evolved many aspects of their physiology to ensure a constant supply of energy to the brain, and in particular, to the neurons. Pericytes and astrocytes orchestrate a tightly regulated neurovascular coupling to adapt nutrient and oxygen provision in response to increased synaptic activity [3]. Glial provision of lactate or pyruvate to neurons reduces their requirement for metabolic pathways or nutrient stores, not directed at the rapid and efficient production of energy [4,5].

Besides these physiological adaptations [6], the complex architecture of neurons has led to the appearance of a set of cellular mechanisms to closely monitor the metabolic state and to respond to changes in regional/local energy levels to maintain metabolic homoeostasis [7,8].

Mitochondria are home of the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) machineries that couples ATP synthesis to oxidation of nutrients through the generation of a proton gradient by the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Mitochondrial energetic metabolism governs the pace of neuronal development, and dysfunction leads to neurodevelopmental disease [9]. In addition, mitochondria fulfil other functions like buffering intracellular calcium levels, regulating cell death pathways and hosting numerous biosynthetic pathways [10,11]. Neurons can also obtain their energy from glycolysis, which has a reduced capacity of generating ATP compared to OXPHOS, but is capable to rapidly react to immediate changes in ATP demand, providing a fast response during neuronal stimulation until oxidative metabolism acquire prevalence [6].

Here, we will discuss our current knowledge on the mechanisms that neurons have in place to meet local energetic demands at the mitochondrial level. We will focus on how local metabolic states in neurons control the transport and distribution of mitochondria, how mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy are controlled spatially, to tune the efficiency of energy generation or to dispose of inefficient mitochondria and what are the signalling pathways that coordinate these processes.

Transport and distribution of mitochondria to where they are needed

Due to their morphological complexity and large size, neurons have in place mechanisms to control the transport to and distribution of mitochondria at regions of high metabolic demands such as synapses [7,12]. To achieve this, mitochondria associate with KIF5 family kinesins and dynein motors for long range anterograde and retrograde transport along microtubules, respectively [13,14]. The TRAK family of motor adaptor proteins provide directional specificity to mitochondrial transport by preferentially interacting with kinesin (TRAK1) or dynein (TRAK2) [15, 16, 17]. TRAK proteins form complexes with the outer mitochondrial membrane proteins, Miro1 and Miro2, that contain EF hand calcium sensing and GTPase domains [18,19] and regulate the activity of the motor complexes [20,21] with Miro1 playing a more prominent role than Miro2 in this regulation [21,22].

In addition, neuronal mitochondria can regulate their transport and distribution using actin filaments [23] perhaps through mitochondrially localized Myosin19 (Myo19) motor [24,25], which couples to Miro proteins for its OMM recruitment and stabilization [21]. In addition to motor driven transport, a wave of actin polymerization and assembly onto the mitochondrial surface [26] can generate asymmetric comet tails that can drive short and fast mitochondrial movements that were shown to be important to shuffle mitochondrial positioning before mitosis although the relevance of this transport mechanism remains to be proved in neurons [27]. Finally, the actin cytoskeleton can be used as an anchorage for mitochondria thereby securing their position to certain locations like synapses and nodes of Ranvier [28,29] where their function might be needed.

Mitochondria can adapt their transport and distribution to match local energy requirements through various mechanisms. An activity-dependent rise in intracellular calcium (e.g. at pre- or post-synapses) can arrest motile mitochondria through Miro1 EF-hand-dependent calcium sensing and uncoupling from the transport pathway [30, 31, 32] to increase the presence of mitochondria in the area thus supporting, both energy provision and calcium buffering capacity to regulate synaptic Ca2+ homoeostasis [33, 34, 35]. However, synaptic activation-dependent calcium rises can still induce the arrest of motile mitochondria in the absence of Miro1 [22,36], suggesting compensation by Miro2 or the existence of other mechanisms of activity-dependent mitochondrial stopping. For example, syntaphilin (SNPH) allows the immobilization of mitochondria following synaptic activity by binding kinesin motors and microtubules [37] assisted at pre-synapses by Myosin VI (Myo6) and actin filaments [29]. Moreover, the phosphorylation of Myo6 by AMPK [29] implies that synaptic mitochondrial capture is governed by the cellular energetic state as AMPK is activated under energy stress conditions with high AMP/ATP ratios, to increase ATP production and restore energy homoeostasis [38,39] (Figure 1). It is still unclear whether a parallel anchoring mechanism is present in dendrites, where large mitochondria are stationary to support post-synaptic function [40]. Should it exist it might involve a similar Myo6 role, or that of other myosins known to regulate mitochondrial motility or anchorage like Myosin V (Myo5) [28] or Myo19, which in turn is known to respond to glucose starvation and to levels of ROS [41,42] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Synaptic immobilization of mitochondria, Maintaining synaptic activity is an energetically expensive task. ATP is needed to regenerate the ion gradients responsible for neuronal excitability. Neurons use different mechanisms to ensure the presence of mitochondria near presynaptic sites to ensure that energy provision matches energy expenditure. One mechanism senses the rise in intracellular Ca2+ due to synaptic activation to stop mitochondria via anchorage by Syntaphilin (SNPH). This mechanism is supported by Myosin 6 phosphorylation dependent anchorage of mitochondria to the actin cytoskeleton which is mediated by AMPK and thus, is regulated by the energetic status of the cell. Myosin 5a (Myo5a) and Myosin 19 (Myo19) are other candidates to mediate actin dependent immobilization of mitochondria in synapses, being Myo19 known to be regulated by both ROS production and glucose availability. Mitochondria can also be stopped at the synapse by a mechanisms that senses high glucose levels driven by the increased abundance of glucose transporters. Glucose is used as a substrate to synthetize UDP-GlcNAc by the Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway. OGT uses UDP-GlcNAc to catalyze the O-GlcNAcylation of TRAK1, which stops mitochondrial motility and is coupled with the FHL2-dependent anchoring of mitochondria to the actin cytoskeleton.

Nutrient levels can also influence CNS mitochondrial dynamics. Increased synaptic activity can induce a rise of intracellular glucose by stimulating the membrane accumulation of glucose transporters [43]. Glucose can influence the machinery of mitochondrial transport and regulate mitochondrial motility and distribution through O-linked N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (OGT), an integral component of the mitochondrial transport machinery [44]. OGT activity responds to local concentrations of UDP-GlcNAc, a high energy donor substrate produced by the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway and thus is a readout of free glucose availability [45]. OGT catalyzes the O-GlcNAcylation of TRAK1 stopping mitochondrial motility [46] through FHL2-dependent anchoring of mitochondria to the F-actin cytoskeleton [47] mediating the accumulation of synaptic mitochondria for an efficient glucose utilization (Figure 1).

Interestingly, enhancing mitochondrial trafficking can also overcome axonal energy crisis and protect against axonal degeneration [48,49]. One mechanism recently identified to enhance axonal motility and protect against injury induced damage involves the local activation of the AKT effector PAK5, which induces the remobilization of stationary damaged mitochondria in axons through phosphorylation of SNPH [50]. This remobilization may help to provide new mitochondria to nerve terminals requiring energy to restore axonal homoeostasis as well as to recycle damaged mitochondria by delivering them to the somatodendritic compartment where they can enter the autophagy pathway [51].

Mitochondrial remodelling in response to energetic balance

Mitochondrial morphology undergoes remodelling through the antagonistic processes of mitochondrial fusion and fission [52]. Mitochondrial fusion is mediated by the concerted action of three large GTPases, Mitofusin 1 and 2 (Mfn1 and Mfn2) located on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) and OPA1 located on the inner mitochondrial membranes (IMM). Mutations in Mfn2 and Opa1 lead to Charcot-Marie-Tooth 2A [53] and Dominant Optic Atrophy [54,55], respectively, highlighting the importance of fusion processes for neuronal function [53, 54, 55]. Mitochondrial fission depends on the activity of Drp1, another large GTPase critical for neuronal development [56,57]. Drp1 is recruited to the OMM from the cytoplasm by its mitochondrial receptors Fis1, MFF, MID49, or MID51, and assembles in a ring structure surrounding mitochondria, that constricts and induces the fission of both mitochondrial membranes assisted by an ER tubule and the local polymerization of actin [58, 59, 60].

Generally, longer and more interconnected (fused) mitochondria correlate with high respiration efficiency [61] and protection against mitophagy [62]. In contrast, mitochondrial fission helps cells to activate apoptotic programs and increases the mitophagic flow [63]. In neurons, a highly interconnected network is typically seen in the somas and dendritic compartment [64], which may facilitate responding to high energy demands and Ca2+ buffering requirements in regions with high density of synapses [40,65]. Mitochondria in axons are shorter, perhaps to facilitate extended transport distances to reach presynaptic sites [66]. Presynaptic capture in terminal boutons of these shorter mitochondria ensures enough local ATP generation and accurate Ca2+ buffering capacity required to support synaptic transmission on these presynaptic sites [33,34,67]. Axonal mitochondrial size, dictated in part by Drp1 and MFF, are critical factors in regulating the Ca2+ buffering capacity of the organelle and synaptic communication as bigger mitochondria with higher buffering capacity might keep local Ca2+ concentration below the threshold required to allow for neurotransmitter release [66].

Studies in non-neuronal cells established that under mild energetic stress like starvation conditions, the mitochondrial network elongates and gains complexity through the induction of mitochondrial fusion in response to activation of the AMPK or inhibition of the mTOR pathways, both protective pathways activated under mild metabolic stress conditions [62,68]. Such increase in mitochondrial fusion is important to sustain cell viability during starvation induced autophagy [69]. In neurons, the AMPK, the PKA/AKAP1 and Calcineurin signalling pathways, activated in response to increased levels of AMP and ADP, extracellular growth signals or synaptic activity, respectively, can also stimulate the elongation of the mitochondrial network by controlling the translocation of Drp1 to the mitochondrial membrane [70,71] (Figure 2). By inhibiting mitochondrial fission, PKA/AKAP1 favours the efficiency of mitochondrial respiration to support energy consumption during neuronal morphogenesis or to protect against ischaemia and cell death after neuronal injury or excitotoxicity [72,73].

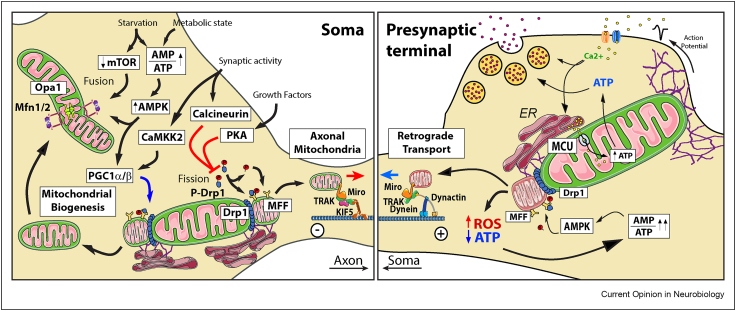

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial dynamics, biogenesis and mitophagy, Neurons regulate mitochondrial remodelling locally in response to the cellular context. Mild energetic stress favours mitochondrial fusion through the AMPK or mTOR pathways. Growth Factors and synaptic activity, through activation of PKA and Calcineurin respectively, may also stimulate mitochondrial elongation by inhibiting the translocation of Drp1 to the mitochondrial membrane and, thus, inhibiting fission. In contrast, Drp1 and MFF activity are critical to ensure that short mitochondria is produced to enter in the axon and populate presynaptic terminals. In addition, similar signalling pathways, like AMPK or CaMKK2, activated by the energetic state or synaptic communication respectively, can also stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis through activation of PCG1. Continuous synaptic activity giving rise to elevated levels of ROS and energy depletion in axons can activate the fission of defective mitochondria though the strong activation of AMPK, which mediates fission instead of fusion by phosphorylation of MFF and recruitment of Drp1 to the mitochondrial membrane. This process help removed dysfunctional mitochondria by coupling this fission to the retrograde mitochondrial transport machinery to deliver these defective mitochondria to the soma where it will fuse to lysosomes and be degraded.

Ca2+ and energy production

Activity-dependent cytoplasmic Ca2+ rises trigger Ca2+ release from the ER which can be taken up by local mitochondria though the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU), a Ca2+ selective ion channel that opens upon high concentrations of cytosolic Ca2+ [74,75]. This mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake generally requires the close apposition of ER and mitochondrial membranes at the ER-mitochondrial contact sites (ERMCS) where high concentrations of cytoplasmic Ca2+ are achieved [76]. However, recent work has challenged the view that in neurons the close apposition of the ER is required for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake [77]. Presynaptic mitochondria shows a low threshold for Ca2+ uptake conferred by the presence of MICU3, a neuronal specific regulator of the MCU complex, which sensitizes these mitochondria to the cytoplasmic Ca2+ fluctuations associated with synaptic activity [77].

The uptake of Ca2+ by the MCU acts as a feedforward mechanism that boosts mitochondrial metabolism by activating the TCA cycle and the respiratory chain, increasing ATP production in different systems [78, 79, 80]. It is worth noting that this point remains controversial in neurons, where recent studies have shown that activity dependent Ca2+ entry might boost synaptic energy homoeostasis by an MCU-independent mechanism [81,82], or that MCU itself, is not required to keep synaptic metabolic homoeostasis [83]. A possible explanation is that an intermembrane space elevation of Ca2+ can stimulate the malate-aspartate shuttle and increase pyruvate availability for the TCA cycle contributing to the increase in activity-dependent energy generation [81,82].

Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake can, reciprocally, shape the dynamics of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and thus regulate local Ca2+ signalling influencing synaptic transmission or excitotoxicity and metabolism [34,35,77,82,84, 85, 86]. Neurons might control the efficiency of energy generation and Ca2+ buffering and thus influence synaptic transmission [76] by controlling the expression levels of MCU, MICU3 or other MCU regulatory subunits [86], or by regulating the amount and functionality of the ERMCS. This can be done by modulating the expression levels and activity of Ca2+ regulatory proteins like IP3R/GRP75/VDAC1 [87,88], the ER-mitochondrial tether proteins like VAPB/PTPIP51 [89,90] or the ER localization of Mfn2 [91].

Mitochondrial biogenesis

The energetic balance of the cell is a strong driving force regulating the generation of de novo mitochondria [87]. Mitochondrial biogenesis is a self-renewing mechanism that requires pre-existing mitochondria [88] and can occur locally in any compartment of the cell [89,90]. This is extremely important in neurons as distal axonal mitochondria that need to be replaced would require many days in reaching their final position if they had to travel from the soma. There needs to be coordination between nuclear and mitochondrial processes to ensure the formation of new mitochondria [91]. First, there should be coordinated mtDNA replication as well as nuclear and mtDNA transcription and translation to produce the mitochondrial components required for the new mitochondrial mass [92]. In addition, the coordinated synthesis and import of mitochondrial components encoded by the nucleus is critical to ensure the stoichiometry and functionality of the mitochondrial components [93,94]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1alpha and -beta (PGC-1α and PGC-1β) are master regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis [95,96] regulating mitochondrial density in axons [97]. Both, PGC-1α and PGC-1β, mediate the activation of the mitochondrial transcription factor TFAM [98] and respond to several signalling pathways, like AMPK, LKB1 or CaMKK2, in turn activated by the energetic balance [99,100] or Ca2+ induced by NMDA receptor activation [101]. Under energy stress conditions, AMPK phosphorylates and activates PGC-1α [102] and Sirt1, which in turn deacetylates PGC-1α reinforcing its activation [103] (Figure 2). Activated PGC-1α stimulates nuclear transcription of TFAM through the upregulation of NRF1/2 which in turn activates the expression of mitochondrial genes [104]. Mitochondrial biogenesis driven by PGC-1α activation and the switch to OXPHOS metabolism has been shown to be critical during motor neuron development [105] and are associated with protection from motor neuron loss in ALS models [106,107]. PGC-1α deficiency was also associated with GABAergic interneuron function [108] and with loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra [109].

Mitophagy and energetic failure

Mitophagy is especially important in neurons, cells that do not divide and that would accumulate, during their lifetime, damaged and inefficient mitochondria [8]. The most common and better described mitophagy mechanism is the damage-induced mitophagy in which PINK1 and Parkin are central players responsible for the identification, isolation and degradation of defective mitochondria [110]. In addition to mitochondrial damage as a trigger, the cell's energetic balance is a key determinant that regulates mitochondrial quality and quantity through the regulation of the mitophagic flow. Inhibition of mTOR under starvation conditions removes the break on ULK1 activation, which leads to beclin1 phosphorylation and autophagosome formation and facilitates mitophagy [87,111]. Likewise, under severe metabolic stress, AMPK activation was shown to stimulate mitophagy [112] at least in part by a similar activation of ULK1 [113]. In this case, the strong activation of AMPK induces fission rather than fusion by phosphorylating MFF and stimulating the activation of Drp1 on the OMM, allowing for the controlled mitophagy of small fragments of defective mitochondria which can be engulfed by an autophagosome [114] (Figure 2). In an analogous mechanism, PINK1 phosphorylation also induces mitochondrial fission allowing the segregation of damaged mitochondria to undergo mitophagy [115]. Under repeated synaptic stimulation, a presynaptic mitochondria is subject of significant energetic pressure and have its OXPHOS system strained. The increased respiration rate is accompanied by an enhanced generation of radical oxygen species (ROS), which might themselves act as signals to locally induce the recycling of parts of the mitochondrial compartment by mitophagy [116] (Figure 2).

Regulation of mitochondria substructure

Mitochondrial internal architecture can vary enormously both within and between cell types and can reflect the metabolic state of that mitochondria and of the cell more broadly [117, 118, 119]. In neurons, synaptic mitochondria exhibit higher cristae density than those in other cellular regions [120], suggesting that cristae architecture is dynamic and can be remodelled to adapt to local energetic and Ca2+ buffering demands [119,121]. This gives rise to a complex synapse/mitochondrial crosstalk by which synaptic activity shapes mitochondrial ultrastructure [122] and thus the functionality of local mitochondria while, reciprocally, these mitochondria critically regulate synaptic performance and homoeostasis [7,33,65,123].

The components of the fusion and fission machineries control cristae structure by influencing inner membrane dynamics directly (via Opa1) or indirectly (Mfn1/2 and Drp1) by regulating the balance between fusion and fission [124]. In addition, Opa1 accomplishes a role in shaping cristae structure and in controlling the release of cytochrome C during apoptosis that is independent of mitochondrial fusion [125] and which may have additional consequences for synaptic transmission [126]. Opa1 function requires, at least in part, the presence of another cristae membrane remodelling player, the F1F0-ATP Synthase [127], which forms dimers that induce membrane curvature and are important for the stabilization of mitochondrial cristae [128,129] implying that metabolically active mitochondria ensures its own cristae stability.

The Mitochondrial Contact Site and Cristae Organising System (MICOS) is another critical regulator of the IMM substructure [130]. MICOS is a large hetero-oligomeric complex composed of two core subcomplexes, Mic60 and Mic10, which accomplishes important roles in the formation and stabilization of tubular or lamellar cristae, respectively [131,132]. MICOS binds the mitochondrial intermembrane space bridging complex (MIB) or Sam complex to form the MICOS-MIB, which attaches both mitochondrial membranes onto the same macromolecular complex [133] (Figure 3). A number of mutations in MICOS components have been identified in patients with different neurodegenerative diseases [134]. Mutations in Mic60 (mitofilin) has been identified in Alzheimers's disease [135] and Parkinson's disease [136], while mutations in Mic14 (CHCHD10) have also been reported in Alzheimers's disease [137] and Charcot-Marie-Tooth [138], highlighting the critical dependence of neurons of an appropriate IMM ultrastructure.

Figure 3.

Regulation of cristae structure by the transport machinery, Mitochondrial ultrastructure is linked to mitochondrial function. Opa1 and the MICOS complexes are two critical regulators of mitochondrial cristae morphology and thus can potentially control mitochondrial energy production. It has recently been identified a molecular bridge between the MICOS complex and the mitochondrial transport machinery that couples both mitochondrial membranes to the transport pathway. This bridge may act as a sensor of intramitochondrial oxidation and thus influence the transport of the organelle. Likewise, the signalling pathways governing mitochondrial trafficking might impact mitochondrial ultrastructure and ultimately energy production.

Super-resolution imaging has allowed the visualization and characterization of the dynamic nature of individual cristae [139] highlighting the idea that cristae are isolated and functionally independent structures that can display different membrane potentials [140]. This advocates for the existence of regulatory mechanisms of energy production involving the participation of a small proportion, or even only one cristae to boost a specific cellular process locally. This idea is supported by the fact that the mitochondrial cristae and the MICOS complexes controlling their structure follow particular, non-random distributions throughout the mitochondria [141]. Moreover, we have known for over a decade that cristae junctions are distributed asymmetrically in presynaptic mitochondria with the mitochondrial side displaying high density of cristae junctions facing the active region of the presynaptic membrane [120]. The recent identification of a molecular bridge between the mitochondrial transport machinery and the MICOS complex [142] that may additionally serve as a transducing machinery of intramitochondrial oxidation [143] and in which metaxins might be involved [144] suggests that the mechanism of cristae junction distribution at such small spatial scale might be regulated by similar cues and signalling pathways as the mitochondrial transport throughout the neuron (Figure 3). The fact that Myo19 controls cristae architecture and energy production [145] and ER-mitochondria association and mitochondrial fission [146] reinforces the vision of an integrated mitochondrial transport and dynamics with the efficiency in energy generation of mitochondrial cristae.

Conclusion

How neurons regulate the local supply of energy in the regions where it is needed is critical to sustain neuronal homoeostasis and function. We have discussed here how this entails the integration of numerous signalling pathways that control the molecular mechanisms governing mitochondrial trafficking and distribution, mitochondrial dynamics, as well as biogenesis and turnover. We argue that a more profound knowledge and understanding of the mechanisms underpinning the metabolic regulations of mitochondrial function, including those governing mitochondrial ultrastructure and bioenergetic function, will provide novel targets for therapeutic intervention to treat a vast range of pathologies in which mitochondrial function is compromised, from metabolic syndromes, neurodegenerative diseases, neurodevelopmental disorders or even pathologies associated with ageing and cancer.

Author contributions

GL-D and JTK wrote the paper.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (WT222519/Z/21/Z) and a Wellcome Trust Collaborative Award (WT223202/Z/21/Z) to Josef T. Kittler.

This review comes from a themed issue on Metabolic underpinnings of normal and diseased neural function 2023

Edited by Russell H. Swerdlow and Inna Slutsky

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Rolfe D.F., Brown G.C. Cellular energy utilization and molecular origin of standard metabolic rate in mammals. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:731–758. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attwell D., Laughlin S.B. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metabol. 2001;21:1133–1145. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attwell D., Buchan A.M., Charpak S., Lauritzen M., Macvicar B.A., Newman E.A. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature. 2010;468:232–243. doi: 10.1038/nature09613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nortley R., Attwell D. Control of brain energy supply by astrocytes. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2017;47:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magistretti P.J., Allaman I. Lactate in the brain: from metabolic end-product to signalling molecule. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:235–249. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2018.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz-Garcia C.M., Mongeon R., Lahmann C., Koveal D., Zucker H., Yellen G. Neuronal stimulation triggers neuronal glycolysis and not lactate uptake. Cell Metabol. 2017;26:361–374 e364. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devine M.J., Kittler J.T. Mitochondria at the neuronal presynapse in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:63–80. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misgeld T., Schwarz T.L. Mitostasis in neurons: maintaining mitochondria in an extended cellular architecture. Neuron. 2017;96:651–666. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata R., Casimir P., Erkol E., Boubakar L., Planque M., Gallego Lopez I.M., Ditkowska M., Gaspariunaite V., Beckers S., Remans D., et al. Mitochondria metabolism sets the species-specific tempo of neuronal development. Science. 2023 doi: 10.1126/science.abn4705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The rate of mitochondrial metabolism dictates the speed of neuronal development impacting dendritic complexity and synaptic function of mature neurons. There is species-specific timeline of mitochondrial dynamics and metabolism underpinning neuronal differences between species.

- 10.Spinelli J.B., Haigis M.C. The multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:745–754. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisner V., Picard M., Hajnoczky G. Mitochondrial dynamics in adaptive and maladaptive cellular stress responses. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:755–765. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0133-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz T.L. Mitochondrial trafficking in neurons. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2013;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirokawa N., Takemura R. Molecular motors and mechanisms of directional transport in neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:201–214. doi: 10.1038/nrn1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saxton W.M., Hollenbeck P.J. The axonal transport of mitochondria. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:2095–2104. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Spronsen M., Mikhaylova M., Lipka J., Schlager M.A., van den Heuvel D.J., Kuijpers M., Wulf P.S., Keijzer N., Demmers J., Kapitein L.C., et al. TRAK/Milton motor-adaptor proteins steer mitochondrial trafficking to axons and dendrites. Neuron. 2013;77:485–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stowers R.S., Megeath L.J., Gorska-Andrzejak J., Meinertzhagen I.A., Schwarz T.L. Axonal transport of mitochondria to synapses depends on milton, a novel Drosophila protein. Neuron. 2002;36:1063–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenton A.R., Jongens T.A., Holzbaur E.L.F. Mitochondrial adaptor TRAK2 activates and functionally links opposing kinesin and dynein motors. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4578. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24862-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birsa N., Norkett R., Higgs N., Lopez-Domenech G., Kittler J.T. Mitochondrial trafficking in neurons and the role of the Miro family of GTPase proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:1525–1531. doi: 10.1042/BST20130234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fransson S., Ruusala A., Aspenstrom P. The atypical Rho GTPases Miro-1 and Miro-2 have essential roles in mitochondrial trafficking. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:500–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo X., Macleod G.T., Wellington A., Hu F., Panchumarthi S., Schoenfield M., Marin L., Charlton M.P., Atwood H.L., Zinsmaier K.E. The GTPase dMiro is required for axonal transport of mitochondria to Drosophila synapses. Neuron. 2005;47:379–393. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez-Domenech G., Covill-Cooke C., Ivankovic D., Halff E.F., Sheehan D.F., Norkett R., Birsa N., Kittler J.T. Miro proteins coordinate microtubule- and actin-dependent mitochondrial transport and distribution. EMBO J. 2018;37:321–336. doi: 10.15252/embj.201696380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Domenech G., Higgs N.F., Vaccaro V., Ros H., Arancibia-Carcamo I.L., MacAskill A.F., Kittler J.T. Loss of dendritic complexity precedes neurodegeneration in a mouse model with disrupted mitochondrial distribution in mature dendrites. Cell Rep. 2016;17:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris R.L., Hollenbeck P.J. Axonal transport of mitochondria along microtubules and F-actin in living vertebrate neurons. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1315–1326. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quintero O.A., DiVito M.M., Adikes R.C., Kortan M.B., Case L.B., Lier A.J., Panaretos N.S., Slater S.Q., Rengarajan M., Feliu M., et al. Human Myo19 is a novel myosin that associates with mitochondria. Curr Biol. 2009;19:2008–2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato O., Sakai T., Choo Y.Y., Ikebe R., Watanabe T.M., Ikebe M. Mitochondria-associated myosin 19 processively transports mitochondria on actin tracks in living cells. J Biol Chem. 2022;298:101883. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this report the authors demonstrate that Myo19 is a processive myosin motor that moves along actin filaments and that can transport mitochondria in living cells. The authors propose that the processivity through actin filaments depends on the dimerization of two molecules of Myo19 by their tail domain.

- 26.Moore A.S., Wong Y.C., Simpson C.L., Holzbaur E.L. Dynamic actin cycling through mitochondrial subpopulations locally regulates the fission-fusion balance within mitochondrial networks. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12886. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A.S., Coscia S.M., Simpson C.L., Ortega F.E., Wait E.C., Heddleston J.M., Nirschl J.J., Obara C.J., Guedes-Dias P., Boecker C.A., et al. Actin cables and comet tails organize mitochondrial networks in mitosis. Nature. 2021;591:659–664. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03309-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This work shows how a wave of actin polymerization in the surface of the mitochondrial membrane can drive short and fast mitochondrial movements generating asymmetric comet tails that propels the mitochondrial unit.

- 28.Pathak D., Sepp K.J., Hollenbeck P.J. Evidence that myosin activity opposes microtubule-based axonal transport of mitochondria. J Neurosci. 2010;30:8984–8992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1621-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Xiong G.J., Huang N., Sheng Z.H. The cross-talk of energy sensing and mitochondrial anchoring sustains synaptic efficacy by maintaining presynaptic metabolism. Nat Metab. 2020;2:1077–1095. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-00289-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this paper the authors show how energy depletion by continued synaptic activity is sensed by the AMPK-PAK pathway which triggers the phosphorylation of myosin VI which mediates the recruitment and anchoring of mitochondria to the filamentous actin found in the pre-synapse.

- 30.Saotome M., Safiulina D., Szabadkai G., Das S., Fransson A., Aspenstrom P., Rizzuto R., Hajnoczky G. Bidirectional Ca2+-dependent control of mitochondrial dynamics by the Miro GTPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20728–20733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808953105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macaskill A.F., Rinholm J.E., Twelvetrees A.E., Arancibia-Carcamo I.L., Muir J., Fransson A., Aspenstrom P., Attwell D., Kittler J.T. Miro1 is a calcium sensor for glutamate receptor-dependent localization of mitochondria at synapses. Neuron. 2009;61:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X., Schwarz T.L. The mechanism of Ca2+ -dependent regulation of kinesin-mediated mitochondrial motility. Cell. 2009;136:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rangaraju V., Calloway N., Ryan T.A. Activity-driven local ATP synthesis is required for synaptic function. Cell. 2014;156:825–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaccaro V., Devine M.J., Higgs N.F., Kittler J.T. Miro1-dependent mitochondrial positioning drives the rescaling of presynaptic Ca2+ signals during homeostatic plasticity. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:231–240. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devine M.J., Szulc B.R., Howden J.H., Lopez-Domenech G., Ruiz A., Kittler J.T. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter haploinsufficiency enhances long-term potentiation at hippocampal mossy fibre synapses. J Cell Sci. 2022:135. doi: 10.1242/jcs.259823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen T.T., Oh S.S., Weaver D., Lewandowska A., Maxfield D., Schuler M.H., Smith N.K., Macfarlane J., Saunders G., Palmer C.A., et al. Loss of Miro1-directed mitochondrial movement results in a novel murine model for neuron disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E3631–E3640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402449111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y., Sheng Z.H. Kinesin-1-syntaphilin coupling mediates activity-dependent regulation of axonal mitochondrial transport. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:351–364. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201302040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia D., Shaw R.J. AMPK: mechanisms of cellular energy sensing and restoration of metabolic balance. Mol Cell. 2017;66:789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang J.S., Tian J.H., Pan P.Y., Zald P., Li C., Deng C., Sheng Z.H. Docking of axonal mitochondria by syntaphilin controls their mobility and affects short-term facilitation. Cell. 2008;132:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rangaraju V., Lauterbach M., Schuman E.M. Spatially stable mitochondrial compartments fuel local translation during plasticity. Cell. 2019;176:73–84 e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shneyer B.I., Usaj M., Wiesel-Motiuk N., Regev R., Henn A. ROS induced distribution of mitochondria to filopodia by Myo19 depends on a class specific tryptophan in the motor domain. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11577. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11002-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shneyer B.I., Usaj M., Henn A. Myo19 is an outer mitochondrial membrane motor and effector of starvation-induced filopodia. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:543–556. doi: 10.1242/jcs.175349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashrafi G., Ryan T.A. Glucose metabolism in nerve terminals. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2017;45:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brickley K., Stephenson F.A. Trafficking kinesin protein (TRAK)-mediated transport of mitochondria in axons of hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18079–18092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.236018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hart G.W., Slawson C., Ramirez-Correa G., Lagerlof O. Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:825–858. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060608-102511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pekkurnaz G., Trinidad J.C., Wang X., Kong D., Schwarz T.L. Glucose regulates mitochondrial motility via Milton modification by O-GlcNAc transferase. Cell. 2014;158:54–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu H., Pekkurnaz G., Falk J., Wei W., Chin M., Steen J., Schwarz T.L. FHL2 anchors mitochondria to actin and adapts mitochondrial dynamics to glucose supply. J Cell Biol. 2021:220. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201912077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This work describes another mechanisms of actin-dependent immobilization of synaptic mitochondria in response to glucose levels. They find that the actin associated protein, FHL2, is recruited to the mitochondria by the O-GlcNAcetylation state of TRAK1 which in turn depends on glucose levels.

- 48.Cartoni R., Norsworthy M.W., Bei F., Wang C., Li S., Zhang Y., Gabel C.V., Schwarz T.L., He Z. The mammalian-specific protein Armcx1 regulates mitochondrial transport during axon regeneration. Neuron. 2016;92:1294–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.10.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Avery M.A., Rooney T.M., Pandya J.D., Wishart T.M., Gillingwater T.H., Geddes J.W., Sullivan P.G., Freeman M.R. WldS prevents axon degeneration through increased mitochondrial flux and enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering. Curr Biol. 2012;22:596–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N., Li S., Xie Y., Han Q., Xu X.M., Sheng Z.H. Reprogramming an energetic AKT-PAK5 axis boosts axon energy supply and facilitates neuron survival and regeneration after injury and ischemia. Curr Biol. 2021;31:3098–3114 e3097. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.04.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Here it is shown how the activation of the AKT-PAK5 signalling pathway during axonal injury and ischaemia induces the remobilization of damaged mitochondria by phosphorylating and inhibiting syntaphilin, an axonal mitochondrial anchor, helping boost energy supply to support neuronal survival and regeneration.

- 51.Lin M.Y., Cheng X.T., Tammineni P., Xie Y., Zhou B., Cai Q., Sheng Z.H. Releasing syntaphilin removes stressed mitochondria from axons independent of mitophagy under pathophysiological conditions. Neuron. 2017;94:595–610 e596. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mishra P., Chan D.C. Mitochondrial dynamics and inheritance during cell division, development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:634–646. doi: 10.1038/nrm3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuchner S., Mersiyanova I.V., Muglia M., Bissar-Tadmouri N., Rochelle J., Dadali E.L., Zappia M., Nelis E., Patitucci A., Senderek J., et al. Mutations in the mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A. Nat Genet. 2004;36:449–451. doi: 10.1038/ng1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alexander C., Votruba M., Pesch U.E., Thiselton D.L., Mayer S., Moore A., Rodriguez M., Kellner U., Leo-Kottler B., Auburger G., et al. OPA1, encoding a dynamin-related GTPase, is mutated in autosomal dominant optic atrophy linked to chromosome 3q28. Nat Genet. 2000;26:211–215. doi: 10.1038/79944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Delettre C., Lenaers G., Griffoin J.M., Gigarel N., Lorenzo C., Belenguer P., Pelloquin L., Grosgeorge J., Turc-Carel C., Perret E., et al. Nuclear gene OPA1, encoding a mitochondrial dynamin-related protein, is mutated in dominant optic atrophy. Nat Genet. 2000;26:207–210. doi: 10.1038/79936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ishihara N., Nomura M., Jofuku A., Kato H., Suzuki S.O., Masuda K., Otera H., Nakanishi Y., Nonaka I., Goto Y., et al. Mitochondrial fission factor Drp1 is essential for embryonic development and synapse formation in mice. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:958–966. doi: 10.1038/ncb1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wakabayashi J., Zhang Z., Wakabayashi N., Tamura Y., Fukaya M., Kensler T.W., Iijima M., Sesaki H. The dynamin-related GTPase Drp1 is required for embryonic and brain development in mice. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:805–816. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friedman J.R., Lackner L.L., West M., DiBenedetto J.R., Nunnari J., Voeltz G.K. ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science. 2011;334:358–362. doi: 10.1126/science.1207385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hatch A.L., Gurel P.S., Higgs H.N. Novel roles for actin in mitochondrial fission. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:4549–4560. doi: 10.1242/jcs.153791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Korobova F., Ramabhadran V., Higgs H.N. An actin-dependent step in mitochondrial fission mediated by the ER-associated formin INF2. Science. 2013;339:464–467. doi: 10.1126/science.1228360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Westermann B. Bioenergetic role of mitochondrial fusion and fission. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:1833–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rambold A.S., Kostelecky B., Elia N., Lippincott-Schwartz J. Tubular network formation protects mitochondria from autophagosomal degradation during nutrient starvation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10190–10195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107402108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Twig G., Elorza A., Molina A.J., Mohamed H., Wikstrom J.D., Walzer G., Stiles L., Haigh S.E., Katz S., Las G., et al. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. 2008;27:433–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Popov V., Medvedev N.I., Davies H.A., Stewart M.G. Mitochondria form a filamentous reticular network in hippocampal dendrites but are present as discrete bodies in axons: a three-dimensional ultrastructural study. J Comp Neurol. 2005;492:50–65. doi: 10.1002/cne.20682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Z., Okamoto K., Hayashi Y., Sheng M. The importance of dendritic mitochondria in the morphogenesis and plasticity of spines and synapses. Cell. 2004;119:873–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lewis T.L., Jr., Kwon S.K., Lee A., Shaw R., Polleux F. MFF-dependent mitochondrial fission regulates presynaptic release and axon branching by limiting axonal mitochondria size. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5008. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07416-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Courchet J., Lewis T.L., Jr., Lee S., Courchet V., Liou D.Y., Aizawa S., Polleux F. Terminal axon branching is regulated by the LKB1-NUAK1 kinase pathway via presynaptic mitochondrial capture. Cell. 2013;153:1510–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morita M., Prudent J., Basu K., Goyon V., Katsumura S., Hulea L., Pearl D., Siddiqui N., Strack S., McGuirk S., et al. mTOR controls mitochondrial dynamics and cell survival via MTFP1. Mol Cell. 2017;67:922–935 e925. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gomes L.C., Di Benedetto G., Scorrano L. During autophagy mitochondria elongate, are spared from degradation and sustain cell viability. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:589–598. doi: 10.1038/ncb2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cereghetti G.M., Stangherlin A., Martins de Brito O., Chang C.R., Blackstone C., Bernardi P., Scorrano L. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15803–15808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808249105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cribbs J.T., Strack S. Reversible phosphorylation of Drp1 by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and calcineurin regulates mitochondrial fission and cell death. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:939–944. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Flippo K.H., Gnanasekaran A., Perkins G.A., Ajmal A., Merrill R.A., Dickey A.S., Taylor S.S., McKnight G.S., Chauhan A.K., Usachev Y.M., et al. AKAP1 protects from cerebral ischemic stroke by inhibiting drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission. J Neurosci. 2018;38:8233–8242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0649-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Merrill R.A., Dagda R.K., Dickey A.S., Cribbs J.T., Green S.H., Usachev Y.M., Strack S. Mechanism of neuroprotective mitochondrial remodeling by PKA/AKAP1. PLoS Biol. 2011;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.De Stefani D., Raffaello A., Teardo E., Szabo I., Rizzuto R. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baughman J.M., Perocchi F., Girgis H.S., Plovanich M., Belcher-Timme C.A., Sancak Y., Bao X.R., Strittmatter L., Goldberger O., Bogorad R.L., et al. Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nature10234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rizzuto R., Brini M., Murgia M., Pozzan T. Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighboring mitochondria. Science. 1993;262:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.8235595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi G., de Juan-Sanz J., Farrell R.J., Ryan T.A. Molecular tuning of the axonal mitochondrial Ca(2+) uniporter ensures metabolic flexibility of neurotransmission. Neuron. 2020;105:678–687 e675. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper shown how neuronal presynaptic mitochondria is sensitive to changes in intracellular calcium due to MICU3. This sensitivity allow mitochondria to uptake calcium during small changes in synaptic activity driven cytosolic calcium and modulate its own metabolism in response to this activity.

- 78.Diaz-Garcia C.M., Meyer D.J., Nathwani N., Rahman M., Martinez-Francois J.R., Yellen G. The distinct roles of calcium in rapid control of neuronal glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Elife. 2021:10. doi: 10.7554/eLife.64821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Duchen M.R. Ca(2+)-dependent changes in the mitochondrial energetics in single dissociated mouse sensory neurons. Biochem J. 1992;283(Pt 1):41–50. doi: 10.1042/bj2830041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kann O., Kovacs R., Heinemann U. Metabotropic receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling elevates mitochondrial Ca2+ and stimulates oxidative metabolism in hippocampal slice cultures. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:613–621. doi: 10.1152/jn.00042.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Liebana I., Juaristi I., Gonzalez-Sanchez P., Gonzalez-Moreno L., Rial E., Podunavac M., Zakarian A., Molgo J., Vallejo-Illarramendi A., Mosqueira-Martin L., et al. A Ca(2+)-dependent mechanism boosting glycolysis and OXPHOS by activating aralar-malate-aspartate shuttle, upon neuronal stimulation. J Neurosci. 2022;42:3879–3895. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1463-21.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this work the authors demonstrate that both glycolysis and neuronal respiration are increased during neuronal activation in a Ca2+-dependent way. The effect is mediated by Aralar, the mitochondrial aspartate-glutamate carrier component of the malate-aspartate shuttle while the mitochondrial calcium uniporter play no relevant effect.

- Zampese E., Wokosin D.L., Gonzalez-Rodriguez P., Guzman J.N., Tkatch T., Kondapalli J., Surmeier W.C., D'Alessandro K.B., De Stefani D., Rizzuto R., et al. Ca(2+) channels couple spiking to mitochondrial metabolism in substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. Sci Adv. 2022;8 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abp8701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study the authors demonstrate that Ca2+ entry after sustained synaptic activity stimulated mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in dopaminergic neurons by two parallel mechanisms, one involving the mitochondrial Calcium uniporter and intramitochondrial calcium entry and another one requiring the malate-aspartate shuttle to feed mitochondrial metabolism.

- 83.Nichols M., Pavlov E.V., Robertson G.S. Tamoxifen-induced knockdown of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter in Thy1-expressing neurons protects mice from hypoxic/ischemic brain injury. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:606. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0607-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Qiu J., Tan Y.W., Hagenston A.M., Martel M.A., Kneisel N., Skehel P.A., Wyllie D.J., Bading H., Hardingham G.E. Mitochondrial calcium uniporter Mcu controls excitotoxicity and is transcriptionally repressed by neuroprotective nuclear calcium signals. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2034. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Groten C.J., MacVicar B.A. Mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake by the MCU facilitates pyramidal neuron excitability and metabolism during action potential firing. Commun Biol. 2022;5:900. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03848-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kwon S.K., Sando R., 3rd, Lewis T.L., Hirabayashi Y., Maximov A., Polleux F. LKB1 regulates mitochondria-dependent presynaptic calcium clearance and neurotransmitter release properties at excitatory synapses along cortical axons. PLoS Biol. 2016;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nazio F., Strappazzon F., Antonioli M., Bielli P., Cianfanelli V., Bordi M., Gretzmeier C., Dengjel J., Piacentini M., Fimia G.M., et al. mTOR inhibits autophagy by controlling ULK1 ubiquitylation, self-association and function through AMBRA1 and TRAF6. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:406–416. doi: 10.1038/ncb2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jornayvaz F.R., Shulman G.I. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays Biochem. 2010;47:69–84. doi: 10.1042/bse0470069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Amiri M., Hollenbeck P.J. Mitochondrial biogenesis in the axons of vertebrate peripheral neurons. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:1348–1361. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Van Laar V.S., Arnold B., Howlett E.H., Calderon M.J., St Croix C.M., Greenamyre J.T., Sanders L.H., Berman S.B. Evidence for compartmentalized axonal mitochondrial biogenesis: mitochondrial DNA replication increases in distal axons as an early response to Parkinson's disease-relevant stress. J Neurosci. 2018;38:7505–7515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0541-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Woodson J.D., Chory J. Coordination of gene expression between organellar and nuclear genomes. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:383–395. doi: 10.1038/nrg2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Couvillion M.T., Soto I.C., Shipkovenska G., Churchman L.S. Synchronized mitochondrial and cytosolic translation programs. Nature. 2016;533:499–503. doi: 10.1038/nature18015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stoldt S., Wenzel D., Kehrein K., Riedel D., Ott M., Jakobs S. Spatial orchestration of mitochondrial translation and OXPHOS complex assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:528–534. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Needs H.I., Protasoni M., Henley J.M., Prudent J., Collinson I., Pereira G.C. Interplay between mitochondrial protein import and respiratory complexes assembly in neuronal health and degeneration. Life. 2021:11. doi: 10.3390/life11050432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Puigserver P., Wu Z., Park C.W., Graves R., Wright M., Spiegelman B.M. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 1998;92:829–839. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lehman J.J., Barger P.M., Kovacs A., Saffitz J.E., Medeiros D.M., Kelly D.P. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 promotes cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:847–856. doi: 10.1172/JCI10268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wareski P., Vaarmann A., Choubey V., Safiulina D., Liiv J., Kuum M., Kaasik A. PGC-1alpha and PGC-1beta regulate mitochondrial density in neurons. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21379–21385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Scarpulla R.C., Vega R.B., Kelly D.P. Transcriptional integration of mitochondrial biogenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 2012;23:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Woods A., Dickerson K., Heath R., Hong S.P., Momcilovic M., Johnstone S.R., Carlson M., Carling D. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta acts upstream of AMP-activated protein kinase in mammalian cells. Cell Metabol. 2005;2:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Woods A., Johnstone S.R., Dickerson K., Leiper F.C., Fryer L.G., Neumann D., Schlattner U., Wallimann T., Carlson M., Carling D. LKB1 is the upstream kinase in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2004–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mairet-Coello G., Courchet J., Pieraut S., Courchet V., Maximov A., Polleux F. The CAMKK2-AMPK kinase pathway mediates the synaptotoxic effects of Abeta oligomers through Tau phosphorylation. Neuron. 2013;78:94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jager S., Handschin C., St-Pierre J., Spiegelman B.M. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12017–12022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Canto C., Gerhart-Hines Z., Feige J.N., Lagouge M., Noriega L., Milne J.C., Elliott P.J., Puigserver P., Auwerx J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gureev A.P., Shaforostova E.A., Popov V.N. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis as a way for active longevity: interaction between the Nrf2 and PGC-1alpha signaling pathways. Front Genet. 2019;10:435. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.O'Brien L.C., Keeney P.M., Bennett J.P., Jr. Differentiation of human neural stem cells into motor neurons stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and decreases glycolytic flux. Stem Cell Dev. 2015;24:1984–1994. doi: 10.1089/scd.2015.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Liang H., Ward W.F., Jang Y.C., Bhattacharya A., Bokov A.F., Li Y., Jernigan A., Richardson A., Van Remmen H. PGC-1alpha protects neurons and alters disease progression in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44:947–956. doi: 10.1002/mus.22217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhao W., Varghese M., Yemul S., Pan Y., Cheng A., Marano P., Hassan S., Vempati P., Chen F., Qian X., et al. Peroxisome proliferator activator receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha) improves motor performance and survival in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:51. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bartley A.F., Lucas E.K., Brady L.J., Li Q., Hablitz J.J., Cowell R.M., Dobrunz L.E. Interneuron transcriptional dysregulation causes frequency-dependent alterations in the balance of inhibition and excitation in Hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2015;35:15276–15290. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1834-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jiang H., Kang S.U., Zhang S., Karuppagounder S., Xu J., Lee Y.K., Kang B.G., Lee Y., Zhang J., Pletnikova O., et al. Adult conditional knockout of PGC-1alpha leads to loss of dopamine neurons. eNeuro. 2016;3 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0183-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pickles S., Vigie P., Youle R.J. Mitophagy and quality control mechanisms in mitochondrial maintenance. Curr Biol. 2018;28:R170–R185. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Russell R.C., Tian Y., Yuan H., Park H.W., Chang Y.Y., Kim J., Kim H., Neufeld T.P., Dillin A., Guan K.L. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:741–750. doi: 10.1038/ncb2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Egan D.F., Shackelford D.B., Mihaylova M.M., Gelino S., Kohnz R.A., Mair W., Vasquez D.S., Joshi A., Gwinn D.M., Taylor R., et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331:456–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kim J., Kundu M., Viollet B., Guan K.L. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Toyama E.Q., Herzig S., Courchet J., Lewis T.L., Jr., Loson O.C., Hellberg K., Young N.P., Chen H., Polleux F., Chan D.C., et al. Metabolism. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates mitochondrial fission in response to energy stress. Science. 2016;351:275–281. doi: 10.1126/science.aab4138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pryde K.R., Smith H.L., Chau K.Y., Schapira A.H. PINK1 disables the anti-fission machinery to segregate damaged mitochondria for mitophagy. J Cell Biol. 2016;213:163–171. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201509003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mungai P.T., Waypa G.B., Jairaman A., Prakriya M., Dokic D., Ball M.K., Schumacker P.T. Hypoxia triggers AMPK activation through reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of calcium release-activated calcium channels. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:3531–3545. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05124-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Neupert W. SnapShot: mitochondrial architecture. Cell. 2012;149:722–722 e721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hackenbrock C.R. Ultrastructural bases for metabolically linked mechanical activity in mitochondria. I. Reversible ultrastructural changes with change in metabolic steady state in isolated liver mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 1966;30:269–297. doi: 10.1083/jcb.30.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cogliati S., Frezza C., Soriano M.E., Varanita T., Quintana-Cabrera R., Corrado M., Cipolat S., Costa V., Casarin A., Gomes L.C., et al. Mitochondrial cristae shape determines respiratory chain supercomplexes assembly and respiratory efficiency. Cell. 2013;155:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Perkins G.A., Tjong J., Brown J.M., Poquiz P.H., Scott R.T., Kolson D.R., Ellisman M.H., Spirou G.A. The micro-architecture of mitochondria at active zones: electron tomography reveals novel anchoring scaffolds and cristae structured for high-rate metabolism. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1015–1026. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1517-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Mannella C.A., Lederer W.J., Jafri M.S. The connection between inner membrane topology and mitochondrial function. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;62:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cserep C., Posfai B., Schwarcz A.D., Denes A. Mitochondrial ultrastructure is coupled to synaptic performance at axonal release sites. eNeuro. 2018;5 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0390-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rossi M.J., Pekkurnaz G. Powerhouse of the mind: mitochondrial plasticity at the synapse. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2019;57:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Liesa M., Shirihai O.S. Mitochondrial dynamics in the regulation of nutrient utilization and energy expenditure. Cell Metabol. 2013;17:491–506. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Frezza C., Cipolat S., Martins de Brito O., Micaroni M., Beznoussenko G.V., Rudka T., Bartoli D., Polishuck R.S., Danial N.N., De Strooper B., et al. OPA1 controls apoptotic cristae remodeling independently from mitochondrial fusion. Cell. 2006;126:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Li Z., Jo J., Jia J.M., Lo S.C., Whitcomb D.J., Jiao S., Cho K., Sheng M. Caspase-3 activation via mitochondria is required for long-term depression and AMPA receptor internalization. Cell. 2010;141:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Quintana-Cabrera R., Quirin C., Glytsou C., Corrado M., Urbani A., Pellattiero A., Calvo E., Vazquez J., Enriquez J.A., Gerle C., et al. The cristae modulator Optic atrophy 1 requires mitochondrial ATP synthase oligomers to safeguard mitochondrial function. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3399. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05655-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Blum T.B., Hahn A., Meier T., Davies K.M., Kuhlbrandt W. Dimers of mitochondrial ATP synthase induce membrane curvature and self-assemble into rows. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:4250–4255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816556116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Strauss M., Hofhaus G., Schroder R.R., Kuhlbrandt W. Dimer ribbons of ATP synthase shape the inner mitochondrial membrane. EMBO J. 2008;27:1154–1160. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pfanner N., van der Laan M., Amati P., Capaldi R.A., Caudy A.A., Chacinska A., Darshi M., Deckers M., Hoppins S., Icho T., et al. Uniform nomenclature for the mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:1083–1086. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201401006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan T., Bruser C., Deckers M., Steyer A.M., Balzarotti F., Barbot M., Behr T.S., Heim G., Hubner W., Ilgen P., et al. MICOS assembly controls mitochondrial inner membrane remodeling and crista junction redistribution to mediate cristae formation. EMBO J. 2020;39 doi: 10.15252/embj.2019104105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Using a combination of super-resolution light microscopy and electron microscopy the authors dissect the specific role of several cristae remodelling factors (the MICOS Mic60 and Mic10 subcomplexes, Opa1 and the F1F0-ATPase complexes) in the formation and stabilization of the mitochondrial cristae architecture.

- 132.Eramo M.J., Lisnyak V., Formosa L.E., Ryan M.T. The 'mitochondrial contact site and cristae organising system' (MICOS) in health and human disease. J Biochem. 2020;167:243–255. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvz111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Huynen M.A., Muhlmeister M., Gotthardt K., Guerrero-Castillo S., Brandt U. Evolution and structural organization of the mitochondrial contact site (MICOS) complex and the mitochondrial intermembrane space bridging (MIB) complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Khosravi S., Harner M.E. The MICOS complex, a structural element of mitochondria with versatile functions. Biol Chem. 2020;401:765–778. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2020-0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Di Domenico F., Sultana R., Barone E., Perluigi M., Cini C., Mancuso C., Cai J., Pierce W.M., Butterfield D.A. Quantitative proteomics analysis of phosphorylated proteins in the hippocampus of Alzheimer's disease subjects. J Proteonomics. 2011;74:1091–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Akabane S., Uno M., Tani N., Shimazaki S., Ebara N., Kato H., Kosako H., Oka T. PKA regulates PINK1 stability and Parkin recruitment to damaged mitochondria through phosphorylation of MIC60. Mol Cell. 2016;62:371–384. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Xiao T., Jiao B., Zhang W., Pan C., Wei J., Liu X., Zhou Y., Zhou L., Tang B., Shen L. Identification of CHCHD10 mutation in Chinese patients with alzheimer disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:5243–5247. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Auranen M., Ylikallio E., Shcherbii M., Paetau A., Kiuru-Enari S., Toppila J.P., Tyynismaa H. CHCHD10 variant p.(Gly66Val) causes axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neurol Genet. 2015;1:e1. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Stephan T., Roesch A., Riedel D., Jakobs S. Live-cell STED nanoscopy of mitochondrial cristae. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12419. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48838-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Wolf D.M., Segawa M., Kondadi A.K., Anand R., Bailey S.T., Reichert A.S., van der Bliek A.M., Shackelford D.B., Liesa M., Shirihai O.S. Individual cristae within the same mitochondrion display different membrane potentials and are functionally independent. EMBO J. 2019;38 doi: 10.15252/embj.2018101056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Stoldt S., Stephan T., Jans D.C., Bruser C., Lange F., Keller-Findeisen J., Riedel D., Hell S.W., Jakobs S. Mic60 exhibits a coordinated clustered distribution along and across yeast and mammalian mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:9853–9858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820364116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Modi S., Lopez-Domenech G., Halff E.F., Covill-Cooke C., Ivankovic D., Melandri D., Arancibia-Carcamo I.L., Burden J.J., Lowe A.R., Kittler J.T. Miro clusters regulate ER-mitochondria contact sites and link cristae organization to the mitochondrial transport machinery. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4399. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12382-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Conradson D.M., Bharat V., Kim M.J., Hsieh C.H., Minhas P.S., Papakyrikos A.M., Durairaj A.S., Ludlam A., Andreasson K.I., et al. A mitochondrial membrane-bridging machinery mediates signal transduction of intramitochondrial oxidation. Nat Metab. 2021;3:1242–1258. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00443-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This work describes the existence of a mechanism that transduces the oxidative state of the mitochondria to an external component, Miro. The oxidative structural changes in this complex will impact mitophagy, cellular metabolism and the redox state of the cell.

- Zhao Y., Song E., Wang W., Hsieh C.H., Wang X., Feng W., Wang X., Shen K. Metaxins are core components of mitochondrial transport adaptor complexes. Nat Commun. 2021;12:83. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study identifies the proteins metaxin1 (MTX1) and metaxin2 (MTX2) as core components of the mitochondrial transport machinery and suggests that metaxins might confer directionality of transport. It also suggests that the molecular motors for mitochondrial trafficking are closely associated with the molecular complexes responsible for protein import into the mitochondria.

- Shi P., Ren X., Meng J., Kang C., Wu Y., Rong Y., Zhao S., Jiang Z., Liang L., He W., et al. Mechanical instability generated by Myosin 19 contributes to mitochondria cristae architecture and OXPHOS. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2673. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30431-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study the authors show that the mitochondrially localized myosin motor, myosin XIX, is critical for maintaining mitochondrial cristae structure, and thus mitochondrial metabolism, by associating with the SAM/MICOS complex.

- Coscia S.M., Thompson C.P., Tang Q., Baltrusaitis E.E., Rhodenhiser J.A., Quintero-Carmona O.A., Ostap E.M., Lakadamyali M., Holzbaur E.L.F. Myo19 tethers mitochondria to endoplasmic reticulum-associated actin to promote mitochondrial fission. J Cell Sci. 2023 doi: 10.1242/jcs.260612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study an additional role of myosin XIX in promoting mitochondrial fission is described. Myosin XIX stabilizes mitochondrial/ER contacts by tethering mitochondria to the ER-associated actin cytoskeleton and thereby promoting mitochondrial fission.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.