Abstract

Paediatric surgeons are expected to counsel patients about the potential risk of cancer post-orchidopexy and the need to self-examine in adulthood. The study objectives were to examine if such advice is being given and identify the stage of cancer at presentation in adult patients with history of orchidopexy. This was a 5-year observational, retrospective collaborative study between a tertiary paediatric surgical unit and its regional adult testicular cancer service, examining the nature of counselling given by paediatric surgeons to orchidopexy patients and their carers and estimating the local incidence of testicular cancer in adults with previous orchidopexy during the same period. Orchidopexy was performed in 228 patients with a mean follow-up of 11.9 months. Twenty-two patients had documented advice to self-examine from puberty onwards. The advice was not influenced whether the surgery was staged or single (p = 0.39). During the 5 years, 133 adults were diagnosed with testicular cancer, 6 (4.5%) were cases of previous cryptorchidism, seminoma (n = 5) and non-seminoma germ cell tumour (n = 1). In our study, the incidence of cryptorchidism in testicular cancer was 4.5%, with all cancer patients presenting with early disease despite documented advice to self-examine being low (9.7%).

Keywords: Orchidopexy, Testicular cancer, Testicular surveillance, Self-assessment advice

Introduction

Undescended testis (UDT) is a commonly encountered condition in paediatric surgery and the most common disorder diagnosed at birth. Congenital UDT is one that has failed to reach a scrotal position at birth while acquired UDT is when a testis re-ascends from a scrotal position [1].

In full-term boys, the incidence of UDT accounts to 1–4.6%. Prematurity and low birth weight are considered strong risk factors. Spontaneous descent is presumed to occur up until the 6th month of life in 35–43% of all affected children [2]. If a testis has not concluded its descent at the age of 6 months (corrected for gestational age), the consensus is to perform the surgery between 6 and 12 months, although some reports can also occur within the first 3–6 months [3].

Boys who are treated for an undescended testis have an increased risk of developing testicular malignancy. Screening and self-examination both during and after puberty are therefore recommended [4].

We aimed to find out the nature of self-assessment advice given to patients, if any, at their final follow-up post-orchidopexy and correlate that with the stage of testicular cancer in patients with history of orchidopexy presenting to our adult testicular cancer service in the same period of time.

Methods

Records of all patients who underwent orchidopexy in a 5-year period from 2013 to 2017 in our tertiary centre were recorded and their discharge letter was checked for self-assessment advice. If advice was not documented it was assumed to have not been given to avoid any ambiguity. Patients who were still under follow-up and not discharged or followed up in a peripheral hospital were excluded. During the same period, we collaborated with our regional adult testicular cancer service to find out the local incidence of testicular cancer in adults and the stage of tumour at presentation and if any had history of cryptorchidism.

Results

We identified 228 patients that underwent orchidopexy for undescended testis in the 5-year period with a mean follow-up in our tertiary centre of 11.9 months (1–40). Two hundred six patients underwent single-stage orchidopexy while 22 patients had staged surgery for intra-abdominal testes. Table 1 shows the demographics of all identified cases.

Table 1.

Demographics of included cases that underwent orchidopexy from 2013 to 2017

| Number of patients | Proportion of total (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Unilateral orchidopexy | 199 | 87.2 |

| Bilateral orchidopexy | 29 | 12.8 |

| Single-stage surgery | 206 | 90.4 |

| Staged surgery | 22 | 9.6 |

| Self-assessment advice given | 22 | 9.6 |

Documented evidence of self-assessment advice was present in 9.6% of patients and was not influenced by the type of surgery performed. Moreover, it was determined to be surgeon independent and did not correlate to age at time of orchidopexy.

During these 5 years, 133 adults were diagnosed with testicular cancer, and 6 were cases of previous congenital undescended testis. Five cases presented with seminoma stage I and one patient was diagnosed with stage IIb non-seminoma germ cell tumour (NSGCT) (Table 2). It was difficult to ascertain whether these patients were performing regular testicular self-examination or whether they were given this advice at time of their orchidopexy.

Table 2.

Cases of testicular cancer with history of cryptorchidism

| Patient | Age of diagnosis | Histology | TNM Staging | Chemo | Age at orchidopexy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19 years | NSGCT | IIa | BEP | 16 years |

| 2 | 25 years | Mixed seminoma* | I | NO | 4 years |

| 3 | 37 years | Pure seminoma | I | NO | Unavailable |

| 4 | 44 years | Pure seminoma | I | Carbo | 9 years |

| 5 | 48 years | Pure seminoma | I | NO | 5 years |

| 6 | 50 years | Pure seminoma | I | Carbo | 12 years |

BEP, bleomycin, etoposide and platinum; Carbo, carboplatin

*Tumour occurred in contralateral side to orchidopexy

Discussion

Long-term prognosis and results following treatment of cryptorchidism follow three lines, cosmoses, fertility and malignancy. Regarding cosmetics, successful surgery for an undescended testis should achieve an adequate scrotal position without atrophy [5]. Poor development of the undescended testis—even after orchidopexy—compared with normal has been proven by many studies [6]. Apart from being smaller in size, operated unilateral cases were shown to be found commonly in a higher scrotal position than the normally descended contralateral testis in adult age [7].

A main objective of orchidopexy in cryptorchidism is to allow for surveillance of testis for early detection of testicular cancer. The relationship between cryptorchidism and testicular tumours was the subject of many studies. There is clinical evidence from long-term follow-up studies that cryptorchidism is associated with a 5- to 10-fold increase in testicular germ cell tumours (TGCT) [8]. According to a recent meta-analysis, the relative risk of developing testicular malignancy in cryptorchidism was 2.2 to 3.8 times more than the normal population [9]. TGCT generally affect 1% of young men with a peak incidence around the age of 25 [10]. It is thought to affect men with a history of cryptorchidism in 10% of cases [11, 12]. In our study, cryptorchidism incidence was 4.5% in the testicular cancer group.

The initial position of the undescended testis was found to be related to the risk of developing TGCT with a greater risk in intra-abdominal and bilateral cases [12, 13]. In UDT, seminoma and embryonal carcinoma are the two most common types [11].

Since the 1940s, multiple hypotheses were thought to be the reason behind the increased risk of testicular cancer in cryptorchidism. Evidence of precursor cells of testicular cancer has been identified in the histological pattern of intratubular germ cell neoplasm (ITGCN) in both adult and paediatric patients [14, 15]. It is currently thought that the exposure of the undescended testis to a higher temperature stimulates abnormal apoptosis transforming gonocytes to ITGCN which eventually can lead to malignancy later in life [16]. Further support to this theory was the detection of placental-like alkaline phosphatase (PLAB)-positive germ cells through childhood in cryptorchid testes. The known fact that PLAB is normally found in gonocytes points toward failure of gonocytes maturation into type A spermatogonia and hence delayed germ cell development [17, 18].

In Unilateral cases, some studies stated that the normally descended testis is at an increased risk of malignancy, although statistically less than the affected side [4] and others suggesting that a tumour in these otherwise normal testes is most probably circumstantial and not indicative of an increased predisposition toward malignancy in a man with a unilateral undescended testis [11].

Early orchidopexy has been shown to reduce the risk of developing testicular cancer. In Denmark, a study of testicular germ cell cancers including 514 patients showed that the odds ratio for testicular cancer is lower the younger the child was at operation. OR was 1.1 for boys aged 0 to 9 years, 2.9 for boys aged 10–14 years and 3.5 in boys more than 15 years [19].

In a recent study comprising of 16,983 men requiring surgical treatment for orchidopexy, it was found that in patients less than 6 years of age, 372 boys need to undergo orchiopexy to prevent a single case of testicular cancer, 1488 boys to prevent exposure to testicular cancer therapy beyond radical orchiectomy and 5315 boys to prevent a single testicular cancer-related death as compared with those with more delayed treatment [20].

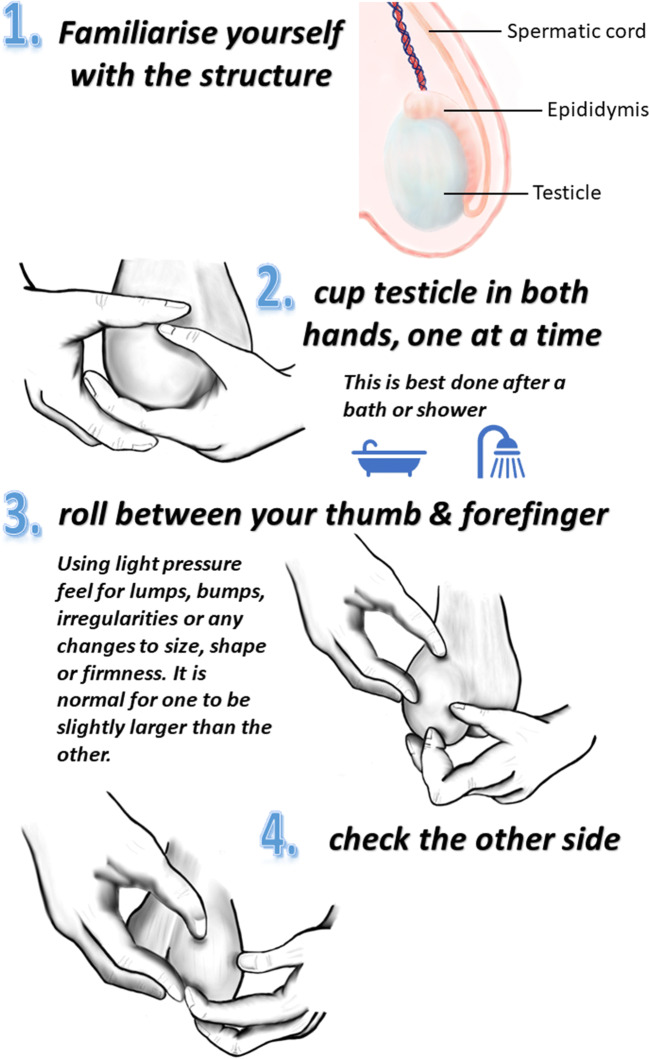

Most guidelines agree on the importance of testicular self-examination after puberty for patients with previous cryptorchidism [21, 22]. However, multiple studies have shown that public awareness of testicular self-examination or even testicular cancer in at risk adult men is scarce and that health care providers do not provide enough information on how to conduct a proper self-exam [23, 24]. In a study done on 300 male students aged 18–35 years, most participants were found generally uninformed on testicular cancer risk and screening procedures. However, they were willing to perform testicular self-examination with promotional pamphlets and one-on-one counselling sessions being their preferred method of health promotion [23]. The technique of testicular self-examination is illustrated in Fig. 1. This is consistent with our study as we found that even in the small number of patients that were given self-assessment advice, no details on the exact method or frequency was documented.

Fig. 1.

The technique of testicular self-examination

Whether giving self-assessment advice to patient’s carers as early as 1–2 years of age at time of discharge after the operation is worthwhile can be a subject of discussion especially that such a conversation can be a source of anxiety and stress to parents and carers. An alternative to that could be arranging for these patients to be followed up again at time of puberty to teach testicular self-examination.

Furthermore, despite the low documented evidence of self-examination, presentation of testicular cancer in these patients seems to be in early stage disease. Whether verbal advice was given at the time of discharge or whether these patients tend to self-examine voluntarily due to their operative history needs to be investigated. However, it is obvious that advice to self-examine given to these patients needs to be improved by being recapitulated around time of puberty along with more details regarding the technique and frequency required.

The authors recognise the limitations of this study. Due to the retrospective nature, there was limited access to data of patients who underwent orchidopexy more than 20 years ago and the nature of the advice given at that time. In addition, although our study included two different cohorts of patients, we believe that this data represents a native population that is being served by the aforementioned two linked tertiary centres. Therefore, we are able to postulate a possible relationship between testicular self-examination advice given to children and the incidence of testicular cancer in adults with previous orchidopexy. Finally, we recognise the change in practice related to management of UDT in particular—the use of minimally invasive surgery—and testicular surveillance advice in recent years.

Conclusion

In our study, the incidence of cryptorchidism in testicular cancer was 4.5%, with all cancer patients presenting with early disease despite low documented advice to self-examine (9.7%). In our opinion, better systems need to be implemented to allow for self-assessment advice to be given to these patients around the age of puberty with precise instructions on how to conduct a proper self-exam.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Ahmed Mohamed, Kevin Murtagh, Roger Kockelbergh and Khalid ElMalik. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Ahmed Mohamed and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

This research study was conducted retrospectively from data obtained for clinical purposes. It is registered with the audit department in the Leicester Royal Infirmary Hospital.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kolon TF, Herndon CD, Baker LA, et al. Evaluation and treatment of cryptorchidism: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2014;192:337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sijstermans K, Hack WW, Meijer RW, van der Voort-Doedens LM. The frequency of undescended testis from birth to adulthood: a review. Int J Androl. 2008;31(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy F (2011) The BAPU consensus statement on the management of undescended testis. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/files/rcs/standards-and-research/commissioning/commissioningguide-for-orchidopexy-published-july-15.pdf

- 4.Dieckmann KP, Pichlmeier U. Clinical epidemiology of testicular germ cell tumors. World J Urol. 2004;22(1):2–14. doi: 10.1007/s00345-004-0398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorup J, Haugen S, Kollin C, Lindahl S, Läckgren G, Nordenskjold A, Taskinen S. Surgical treatment of undescended testes. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(5):631–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadov S, Koskenniemi JJ, Virtanen HE, Perheentupa A, Petersen JH, Skakkebaek NE, Main KM, Toppari J. Testicular growth during puberty in boys with and without a history of congenital cryptorchidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(6):2570–2577. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortes D, Thorup JM, Lindenberg S. Fertility potential after unilateral orchiopexy: simultaneous testicular biopsy and orchiopexy in a cohort of 87 patients. J Urol. 1996;155(3):1061–1065. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66392-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guminska A, Oszukowska E, Kuzanski W, et al. Less advanced testicular dysgenesis is associated by a higher prevalence of germ cell neoplasia. Int J Androl. 2010;33(1):153–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lip SZ, Murchison LE, Cullis PS, et al. A metaanalysis of the risk of boys with isolated cryptorchidism developing testicular cancer in later life. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(1):20–26. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skakkebaek NE, Berthelsen JG, Müller J. Carcinoma-in-situ of the undescended testis. Urol Clin North Am. 1982;9(3):377–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood HM, Elder JS. Cryptorchidism and testicular cancer: separating fact from fiction. J Urol. 2009;181(2):452–461. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, Pike MC. Risk of testicular cancer in cohort of boys with cryptorchidism. BMJ. 1997;314:1507–1511. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7093.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmignani L, Morabito A, Gadda F, et al. Prognostic parameters in adult impalpable ultrasonographic lesions of the testicle. J Urol. 2005;174:1035–1038. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000170236.01129.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berney DM, Looijenga LHJ, Idrees M, Oosterhuis JW, Rajpert-de Meyts E, Ulbright TM, Skakkebaek NE. Germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS): evolution of the current nomenclature for testicular preinvasive germ cell malignancy. Histopathology. 2016;69(1):7–10. doi: 10.1111/his.12958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cortes D, Thorup JM, Visfeldt J. Cryptorchidism: aspects of fertility and neoplasms. A study including data of 1,335 consecutive boys who underwent testicular biopsy simultaneously with surgery for cryptorchidism. Horm Res. 2001;55(1):21–27. doi: 10.1159/000049959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutson JM. Journal of Pediatric Surgery-Sponsored Fred McLoed Lecture. Undescended testis: the underlying mechanism and the effects on germ cells that cause infertility and cancer. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(5):903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kvist K, Clasen-Linde E, Cortes D, et al. Adult immunohistochemical markers fail to detect intratubular germ cell neoplasia in prepubertal boys with cryptorchidism. J Urol. 2014;191(4):1084–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clasen-Linde E, Kvist K, Cortes D, Thorup J. The value of positive Oct3/4 and D2-40 immunohistochemical expression in prediction of germ cell neoplasia in prepubertal boys with cryptorchidism. Scand J Urol. 2016;50(1):74–79. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2015.1088061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moller H, Evans H. Epidemiology of gonadal germ cell cancer in males and females. APMIS. 2003;111(1):43–46. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2003.11101071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins M, Smith DE, Gao D, Wilcox D, Cost NG, Saltzman AF (2019) The impact of age at orchiopexy on testicular cancer outcomes. World J Urol 10 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Radmayr C, Dogan HS, Hoebeke P, Kocvara R, Nijman R, Silay S, Stein R, Undre S, Tekgul S. Management of undescended testes: European Association of Urology/European Society for Paediatric Urology Guidelines. J Pediatr Urol. 2016;12(6):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braga LH, Lorenzo AJ, Romao RLP. Canadian Urological Association-Pediatric Urologists of Canada (CUA-PUC) guideline for the diagnosis, management, and followup of cryptorchidism. Can Urol Assoc J. 2017;11(7):E251–E260. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rovito MJ, Gordon TF, Bass SB, Ducette J. Perceptions of testicular cancer and testicular self-examination among college men: a report on intention, vulnerability, and promotional material preferences. Am J Mens Health. 2011;5(6):500–507. doi: 10.1177/1557988311409023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuzgunbay B, OzgurYaycioglu BS, et al. Public awareness of testicular cancer and self-examination in Turkey: a multicenter study of Turkish Urooncology Society. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(3):386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]