Abstract

One of the main causes of failure of fluorescence in situ hybridization with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotides, besides low cellular ribosome content and impermeability of cell walls, is the inaccessibility of probe target sites due to higher-order structure of the ribosome. Analogous to a study on the 16S rRNA (B. M. Fuchs, G. Wallner, W. Beisker, I. Schwippl, W. Ludwig, and R. Amann, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4973–4982, 1998), the accessibility of the 23S rRNA of Escherichia coli DSM 30083T was studied in detail with a set of 184 CY3-labeled oligonucleotide probes. The probe-conferred fluorescence was quantified flow cytometrically. The brightest signal resulted from probe 23S-2018, complementary to positions 2018 to 2035. The distribution of probe-conferred cell fluorescence in six arbitrarily set brightness classes (classes I to VI, 100 to 81%, 80 to 61%, 60 to 41%, 40 to 21%, 20 to 6%, and 5 to 0% of the brightness of 23S-2018, respectively) was as follows: class I, 3%; class II, 21%; class III, 35%; class IV, 18%; class V, 16%; and class VI, 7%. A fine-resolution analysis of selected areas confirmed steep changes in accessibility on the 23S RNA to oligonucleotide probes. This is similar to the situation for the 16S rRNA. Indeed, no significant differences were found between the hybridization of oligonucleotide probes to 16S and 23S rRNA. Interestingly, indications were obtained of an effect of the type of fluorescent dye coupled to a probe on in situ accessibility. The results were translated into an accessibility map for the 23S rRNA of E. coli, which may be extrapolated to other bacteria. Thereby, it may contribute to a better exploitation of the high potential of the 23S rRNA for identification of bacteria in the future.

Probing with 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotides has become an important tool for the monitoring of microbial populations (3, 10). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) allows the identification of individual cells in complex environments (3). One of the main problems of FISH, besides low cellular ribosome content and impermeability of cell walls, is the inaccessibility of probe target sites due to the higher-order structure of the ribosome (6). Furthermore, despite its length of approximately 1,500 nucleotides, it is sometimes impossible to find suitable signature sites on the 16S rRNA for the identification of the organism(s) of interest. The 23S rRNA, with its length of approximately 3,000 nucleotides, would be the ideal alternative as a probe target molecule. Like the 16S rRNA, it is present in high copy number in all living cells. Its structure and function are highly conserved (13). A drawback is that there are currently only approximately 1,000 full-length 23S rRNA sequences in the databases, compared to more than 18,000 16S rRNA sequences (8). In the age of genome sequencing, it can safely be predicted that this gap will be closing. The availability of a sufficiently large database will allow researchers to exploit the high potential of the 23S rRNA for probe design, which is, considering only the average length of the 16S and the 23S rRNA, twice as large as that of the 16S rRNA. With a study on the in situ accessibility of the 23S rRNA of Escherichia coli to CY3-labeled oligonucleotides, we want to contribute to this development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultivation and sequencing.

Escherichia coli K-12 (DSM 30083T; DSMZ—Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) was grown according to the DSMZ catalogue of strains. Cells were harvested in logarithmic growth phase at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 by centrifugation for 5 min at 4,500 × g. Cells were washed once with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (130 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.2]) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde as described previously (2). The 23S rRNA gene of E. coli was amplified directly from freshly harvested cells by PCR as described previously (12). The 5′ half of the 23S rDNA was amplified with primer pair 23-1V (5′-TTGTGAGGTTAAGCGACT-3′) and 23S-1534R (5′-TAGTGCCTCGTCATCACG-3′), and the 3′ half was amplified with pair 23S-1517V (5′-CGTGATGACGAGGCACTA-3′) and 23S-2904R (5′-CGGCGTTGTAAGGTTAAG-3′). After subsequent purification with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), both strands of the PCR product were sequenced on a 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and on a Licor 4000 (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). The sequence was deposited at the EMBL database under the accession number AJ278710.

Probe design.

The standard probe set consisted of neighboring probes covering the full 23S rRNA of E. coli. For fine mapping, additional probes with overlapping target sites were designed. Self-complementarity of probes of more than three nucleotides was avoided. The standard probe length of 18 nucleotides was varied if the estimated dissociation temperature (Td), according to the 4+2 formula of Suggs (11) [Td = 4 · (G + C) + 2 · (A + T)], exceeded 60°C or was below 48°C (6). All probes used in this study are listed with their sequences and target positions in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sequences and relative fluorescence intensities of a set of oligonucleotide probes targeting the 23S ribosomal RNA of E. coli K-12

| Probe name | E. coli position (5′→3′)a | Probe sequence (5′→3′) | Relative probe fluorescence (%)b | Brightness class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23S-1 | 1–18 | ACGCTTAGTCGCTTAACC | 34 | IV |

| 23S-19 | 19–36 | CCAGGGCATCCACCGTGT | 55 | III |

| 23S-37 | 37–54 | CTTCATCGCCTCTGACTG | 61 | II |

| 23S-55 | 55–72 | ATCGCAGATTAGCACGTC | 51 | III |

| 23S-73 | 73–90 | ATCACCTCACCGACGCTT | 52 | III |

| 23S-91 | 91–108 | CCGGTTATAACGGTTCAT | 27 | IV |

| 23S-109 | 109–126 | TTCCCCATTCGGAAATCG | 38 | IV |

| 23S-127 | 127–144 | TGTCGAAACACACTGGGT | 46 | III |

| 23S-145 | 145–163 | GATTCAGTTAATGATAGTG | 3 | VI |

| 23S-164 | 164–181 | TCGCCTCATTAACCTATG | 58 | III |

| 23S-182 | 182–199 | TGTTTCAGTTCCCCCGGT | 69 | II |

| 23S-200 | 200–217 | TTCCTCGGGGTACTTAGA | 33 | IV |

| 23S-218 | 218–235 | AATCTCGGTTGATTTCTT | 81 | I |

| 23S-236 | 236–252 | CTCGCCGCTACTGGGGG | 72 | II |

| 23S-253 | 253–269 | GGGCTCCTCCCCGTTCG | 57 | III |

| 23S-270 | 270–287 | CACACTGATTCAGGCTCT | 48 | III |

| 23S-288 | 288–305 | GACGCTTCCACTAACACA | 14 | V |

| 23S-306 | 306–323 | GTATCGCGCGCCTTTCCA | 61 | II |

| 23S-324 | 324–341 | GTACGGGGCTGTCACCCT | 63 | II |

| 23S-342 | 342–360 | ACAATATGTGCATTTTTGT | 13 | V |

| 23S-361 | 361–378 | GCCCTACTCATCGAGCTC | 68 | II |

| 23S-369 | 369–386 | CGTGTCCCGCCCTACTCA | 72 | II |

| 23S-387 | 387–404 | TATTCAGACAGGATACCA | 22 | IV |

| 23S-397 | 397–414 | GGTCCCCCCATATTCAGA | 74 | II |

| 23S-415 | 415–432 | TATTTAGCCTTGGAGGAT | 69 | II |

| 23S-433 | 433–450 | CTATCGGTCAGTCAGGAG | 67 | II |

| 23S-451 | 451–468 | CCTCACGGTACTGGTTCA | 66 | II |

| 23S-469 | 469–486 | GGGTTCTTTTCGCCTTTC | 77 | II |

| 23S-487 | 487–504 | TTTTCACTCCCCTCGCCG | 58 | III |

| 23S-505 | 505–522 | TACACGGTTTCAGGTTCT | 32 | IV |

| 23S-523 | 523–540 | GCTCCCACTGCTTGTACG | 79 | II |

| 23S-529 | 529–546 | AAAGAGGCTCCCACTGCT | 66 | II |

| 23S-547 | 547–564 | GTACGCAGTCACCCCCAT | 45 | III |

| 23S-560 | 560–577 | CATTATACAAAAGGTACG | 31 | IV |

| 23S-578 | 578–595 | GAATATAAGTCGCTGACC | 11 | V |

| 23S-596 | 596–613 | TCGGTTAACCTTGCTACA | 29 | IV |

| 23S-614 | 614–631 | TCCCTTCGGCTCCCCTAT | 66 | II |

| 23S-632 | 632–649 | CCCAGTTAAGACTCGGTT | 36 | IV |

| 23S-650 | 650–667 | ATACCCTGCAACTTAACG | 23 | IV |

| 23S-668 | 668–685 | TCACCGGGTTTCGGGTCT | 53 | III |

| 23S-686 | 686–703 | AACCTGCCCATGGCTAGA | 32 | IV |

| 23S-704 | 704–721 | TAGTGTTACCCAACCTTC | 23 | IV |

| 23S-722 | 722–739 | TCGGTTCGGTCCTCCAGT | 54 | III |

| 23S-731 | 731–748 | CAACATTAGTCGGTTCGG | 3 | VI |

| 23S-749 | 749–766 | AGTCATCCGCTAATTTTT | 14 | V |

| 23S-759 | 759–776 | CCCAGCCACAAGTCATCC | 48 | III |

| 23S-777 | 777–794 | TTTGATTGGCCTTTCACC | 58 | III |

| 23S-795 | 795–812 | GAACCAGCTATCTCCCGG | 61 | II |

| 23S-813 | 813–830 | CTAAATAGCTTTCGGGGA | 43 | III |

| 23S-831 | 831–848 | GAATTCACGAGGCGCTAC | 38 | IV |

| 23S-849 | 849–866 | TGCTCTACCCCCGGAGAT | 37 | IV |

| 23S-867 | 867–884 | ACCCCCTTGCCGAAACAG | 39 | IV |

| 23S-885 | 885–902 | GGTTGGTAAGTCGGGATG | 6 | V |

| 23S-903 | 903–920 | TATTCGCAGTTTGCATCG | 10 | V |

| 23S-921 | 921–938 | CGTGATAACATTCTCCGG | 3 | VI |

| 23S-930 | 930–947 | TGTGTCTCCCGTGATAAC | 37 | IV |

| 23S-939 | 939–955 | ACCCGCCGTGTGTCTCC | 49 | III |

| 23S-948 | 948–964 | GACGTTAGCACCCGCCG | 14 | V |

| 23S-956 | 956–973 | TTCACGACGGACGTTAGC | 4 | VI |

| 23S-965 | 965–982 | GTTTCCCTCTTCACGACG | 51 | III |

| 23S-974 | 974–991 | GTCTGGGTTGTTTCCCTC | 94 | I |

| 23S-992 | 992–1009 | TTGGGACCTTAGCTGGCG | 62 | II |

| 23S-1010 | 1010–1027 | TCCCACTTAACCATGACT | 56 | III |

| 23S-1028 | 1028–1045 | GGGCCTTCCCACATCGTT | 62 | II |

| 23S-1046 | 1046–1063 | CCAACATCCTGGCTGTCT | 53 | III |

| 23S-1064 | 1064–1081 | ATGATGGCTGCTTCTAAG | 42 | III |

| 23S-1082 | 1082–1100 | GCTATTACGCTTTCTTTAA | 42 | III |

| 23S-1101 | 1118–1118 | GGCCGACTCGACCAGTGA | 65 | II |

| 23S-1137 | 1137–1154 | CGGTGCATGGTTTAGCCC | 59 | III |

| 23S-1155 | 1155–1172 | GTGTCGCTGCCGCAGCTT | 60 | III |

| 23S-1173 | 1173–1191 | CCTACCCAACAACACATA | 58 | III |

| 23S-1192 | 1192–1209 | AGGCTTACAGAACGCTCC | 49 | III |

| 23S-1210 | 1210–1227 | CTCACAGGCCACCTTCAC | 61 | II |

| 23S-1228 | 1228–1245 | CTGATACCTCCAGCAACC | 32 | IV |

| 23S-1246 | 1246–1263 | ATGTCAGCATTCGCACTT | 61 | II |

| 23S-1264 | 1264–1281 | CCCGCTTTATCGTTACTT | 66 | II |

| 23S-1282 | 1282–1299 | CGGCGAGCGGGCTTTTCA | 42 | III |

| 23S-1300 | 1300–1317 | CAGGAACCCTTGGTCTTC | 66 | II |

| 23S-1310 | 1310–1327 | TAACGTTGGACAGGAACC | 44 | III |

| 23S-1328 | 1328–1345 | GACTCACCCTGCCCCGAT | 68 | II |

| 23S-1336 | 1336–1353 | TAGGGGTCGACTCACCCT | 63 | II |

| 23S-1354 | 1354–1370 | GCCTTTCGGCCTCGCCT | 52 | III |

| 23S-1371 | 1371–1388 | CTGTTTCCCATCGACTAC | 59 | III |

| 23S-1389 | 1389–1407 | CAAGTACAGGAATATTAAC | 3 | VI |

| 23S-1408 | 1408–1425 | CCCCCTTCGCAGTAACAC | 64 | II |

| 23S-1426 | 1426–1443 | AACATAGCCTTCTCCGTC | 74 | II |

| 23S-1444 | 1444–1460 | ACAACCGTCGCCCGGCC | 31 | IV |

| 23S-1461 | 1461–1478 | CTACACGCTTAAACCGGG | 6 | V |

| 23S-1467 | 1467–1484 | ACCAGCCTACACGCTTAA | 7 | V |

| 23S-1479 | 1479–1496 | TTTGCCTGGAAAACCAGC | 1 | VI |

| 23S-1485 | 1485–1502 | TCCGGATTTGCCTGGAAA | 7 | V |

| 23S-1491 | 1491–1508 | TGGTTTTCCGGATTTGCC | 9 | V |

| 23S-1497 | 1497–1514 | CAGCCTTGGTTTTCCGGA | 83 | I |

| 23S-1509 | 1509–1526 | GTCATCACGCCTCAGCCT | 45 | III |

| 23S-1515 | 1515–1532 | TGCCTCGTCATCACGCCT | 56 | III |

| 23S-1524 | 1524–1541 | GCACCGTAGTGCCTCGTC | 6 | V |

| 23S-1533 | 1533–1551 | TGTCGCTTCAGCACCGTAG | 15 | V |

| 23S-1552 | 1552–1569 | TCCTGGAAGCAGGGCATT | 24 | IV |

| 23S-1570 | 1570–1587 | CTGATGCTTAGAGGCTTT | 10 | V |

| 23S-1588 | 1588–1605 | GGTACGATTTGATGTTAC | 6 | V |

| 23S-1606 | 1606–1623 | CCACCTGTGTCGGTTTGG | 64 | II |

| 23S-1615 | 1615–1632 | TCTACCTGACCACCTGTG | 58 | III |

| 23S-1633 | 1633–1650 | TCAAGCGCCTTGGTATTC | 65 | II |

| 23S-1642 | 1642–1659 | CGAGTTCTCTCAAGCGCC | 62 | II |

| 23S-1660 | 1660–1677 | TTGCCTAGTTCCTTCACC | 57 | III |

| 23S-1678 | 1678–1695 | CGAAGTTACGGCACCATT | 41 | III |

| 23S-1696 | 1696–1713 | TATCAGCGTGCCTTCTCC | 94 | I |

| 23S-1714 | 1714–1731 | CAAGTCGCTTCACCTACA | 26 | IV |

| 23S-1732 | 1732–1749 | TGATTTCAGCTCCACGAG | 17 | V |

| 23S-1750 | 1750–1767 | CCAGCTGGTATCTTCGAC | 59 | III |

| 23S-1768 | 1768–1786 | TTTTAATAAACAGTTGCAG | 36 | IV |

| 23S-1787 | 1787–1804 | GTTTGCACAGTGCTGTGT | 57 | III |

| 23S-1805 | 1805–1822 | GTATACGTCCACTTTCGT | 58 | III |

| 23S-1823 | 1823–1839 | CGGGCAGGCGTCACACC | 58 | III |

| 23S-1840 | 1840–1857 | CAATTAACCTTCCGGCAC | 53 | III |

| 23S-1858 | 1858–1875 | CGCTACCGCTAACCCCAT | 12 | V |

| 23S-1876 | 1876–1893 | GGCTTCGATCAAGAGCTT | 8 | V |

| 23S-1894 | 1894–1910 | CGGCCGCCGTTTACCGG | 35 | IV |

| 23S-1911 | 1911–1928 | TTAGGACCGTTATAGTTA | 8 | V |

| 23S-1929 | 1929–1946 | ACAAGGAATTTCGCTACC | 56 | III |

| 23S-1936 | 1936–1953 | TTACCCGACAAGGAATTT | 28 | IV |

| 23S-1954 | 1954–1971 | ATTCGTGCAGGTCGGAAC | 59 | III |

| 23S-1965 | 1965–1982 | ATCATTACGCCATTCGTG | 58 | III |

| 23S-1983 | 1983–1999 | GTGGAGACAGCCTGGCC | 34 | IV |

| 23S-2000 | 2000–2017 | AATTTCACTGAGTCTCGG | 41 | III |

| 23S-2018 | 2018–2035 | CATCTTCACAGCGAGTTC | 100 | I |

| 23S-2036 | 2036–2053 | CTTGCCGCGGGTACACTG | 45 | III |

| 23S-2054 | 2054–2071 | TTCACGGGGTCTTTCCGT | 50 | III |

| 23S-2072 | 2072–2089 | GTCAAGCTATAGTAAAGG | 3 | VI |

| 23S-2090 | 2090–2107 | CAAGGCTCAATGTTCAGT | 3 | VI |

| 23S-2099 | 2099–2116 | CCTACACATCAAGGCTCA | 41 | III |

| 23S-2108 | 2108–2125 | CCCACCTATCCTACACAT | 63 | II |

| 23S-2117 | 2117–2134 | TCAAAGCCTCCCACCTAT | 22 | IV |

| 23S-2126 | 2126–2143 | GTCCACACTTCAAAGCCT | 3 | VI |

| 23S-2144 | 2144–2161 | GGCTCCATGCAGACTGGC | 3 | VI |

| 23S-2162 | 2162–2179 | GGGTGGTATTTCAAGGTC | 7 | V |

| 23S-2180 | 2180–2199 | TTAGAACATCAAACATTAAA | 1 | VI |

| 23S-2200 | 2200–2217 | CCGGATTACGGGCCAACG | 9 | V |

| 23S-2218 | 2218–2235 | CCAGACACTGTCCGCAAC | 48 | III |

| 23S-2227 | 2227–2244 | AACTACCCACCAGACACT | 48 | III |

| 23S-2236 | 2236–2253 | CCCCAGTCAAACTACCCA | 81 | I |

| 23S-2245 | 2245–2262 | AGGAGACCGCCCCAGTCA | 59 | III |

| 23S-2254 | 2254–2271 | CTCTTTAGGAGGAGACCG | 10 | V |

| 23S-2263 | 2263–2280 | CCTCCGTTACTCTTTAGG | 47 | III |

| 23S-2272 | 2272–2289 | CTTCGTGCTCCTCCGTTA | 75 | II |

| 23S-2290 | 2290–2307 | CGACCAGGATTAGCCAAC | 24 | IV |

| 23S-2308 | 2308–2325 | CACTAACCTCCTGATGTC | 61 | II |

| 23S-2326 | 2326–2343 | AGCTGGCTTATGCCATTG | 50 | III |

| 23S-2344 | 2344–2361 | CCGTCACGCTCGCAGTCA | 71 | II |

| 23S-2362 | 2362–2379 | CTTTCGCACCTGCTCGCG | 64 | II |

| 23S-2380 | 2380–2397 | CCGGATCACTATGACCTG | 62 | II |

| 23S-2398 | 2398–2415 | CCCTTCCATTCAGAACCA | 63 | II |

| 23S-2416 | 2416–2433 | TTATCCGTTGAGCGATGG | 31 | IV |

| 23S-2434 | 2434–2451 | TTATCCCCGGAGTACCTT | 45 | III |

| 23S-2452 | 2452–2469 | TTGGGCGGTATCAGCCTG | 23 | IV |

| 23S-2470 | 2470–2487 | CGCCGTCGATATGAACTC | 10 | V |

| 23S-2488 | 2488–2505 | CATCGAGGTGCCAAACAC | 13 | V |

| 23S-2506 | 2506–2523 | CAGGATGTGATGAGCCGA | 16 | V |

| 23S-2514 | 2514–2531 | TTCAGCCCCAGGATGTGA | 14 | V |

| 23S-2532 | 2532–2549 | CATACCCTTGGGACCTAC | 19 | V |

| 23S-2542 | 2542–2559 | GGCGAACAGCCATACCCT | 19 | V |

| 23S-2560 | 2560–2577 | TCGCGTACCACTTTAAAT | 43 | III |

| 23S-2578 | 2578–2595 | CGACGTTCTAAACCCAGC | 45 | III |

| 23S-2596 | 2596–2613 | AGGGACCGAACTGTCTCA | 55 | III |

| 23S-2614 | 2614–2630 | CAGCGCCCACGGCAGAT | 23 | IV |

| 23S-2631 | 2631–2648 | CAGCCCCCCTCAGTTCTC | 67 | II |

| 23S-2649 | 2649–2666 | GTCCTCTCGTACTAGGAG | 51 | III |

| 23S-2667 | 2667–2684 | AGTGATGCGTCCACTCCG | 44 | III |

| 23S-2685 | 2685–2702 | CATGACAACCCGAACACC | 9 | V |

| 23S-2703 | 2703–2720 | ACCGGGCAGTGCCATTGG | 21 | IV |

| 23S-2721 | 2721–2738 | TCTCTTCCGCATTTAGCT | 59 | III |

| 23S-2739 | 2739–2756 | AGATGCTTTCAGCACTTA | 5 | VI |

| 23S-2757 | 2757–2774 | GGGGCAAGTTTCGTGCTT | 27 | IV |

| 23S-2775 | 2775–2792 | TCAGGGAGAACTCATCTC | 37 | IV |

| 23S-2781 | 2781–2798 | TAAGTCTCAGGGAGAACT | 12 | V |

| 23S-2799 | 2799–2816 | CGTTCCTTCAGGAGACTC | 51 | III |

| 23S-2811 | 2811–2828 | CGTCGTCTTCAACGTTCC | 60 | III |

| 23S-2829 | 2829–2846 | CACCCGGCCTATCAACGT | 60 | III |

| 23S-2840 | 2840–2857 | CTGCGCTTACACACCCGG | 58 | III |

| 23S-2858 | 2858–2875 | GGTTAGCTCAACGCATCG | 60 | III |

| 23S-2865 | 2865–2882 | TAGTACCGGTTAGCTCAA | 48 | III |

| 23S-2883 | 2883–2900 | TTAAGCCTCACGGTTCAT | 44 | III |

| 23S-2887 | 2887–2904 | AAGGTTAAGCCTCACGGT | 36 | IV |

E. coli position according to the numbering of Brosius et al. (5).

Fluorescence intensities expressed as a percentage of that of the brightest probe detected, 23S-2018.

Probe labeling and quality control.

Probes were synthesized monolabeled at the 5′ end with either CY3, carboxyfluorescein (FAM), or carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) by Interactiva GmbH (Ulm, Germany). Aliquots of each probe were analyzed in a spectrophotometer (UV-1202; Shimadzu, Duisburg, Germany). The peak ratios of the absorption of DNA at 260 nm and the absorption of the respective dye were determined in order to check the labeling quality of the oligonucleotides (6).

FISH.

As described previously (6), approximately 4 × 106 cells were hybridized in 80 μl of buffer containing 0.9 M sodium chloride, 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), and 1.5 ng of fluorescent probe μl−1 at 46°C for 2 h. Subsequently, cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 2 min at 4,000 × g, the supernatant was discharged, and the cells were resuspended in 100 μl of hybridization buffer containing no probe. After being washed for 20 min at 46°C, samples were mixed with 300 μl of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (pH 9.0 for FAM-labeled probes), immediately placed on ice, and analyzed within 3 h.

Flow cytometry.

Probe-conferred fluorescence of hybridized cells was quantified by a FACStar Plus flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). For CY3- and TAMRA-labeled probes, the argon ion laser was tuned to an output power of 750 mW at 514 nm. Forward-angle light scatter (FSC) was detected with a BP 530/30 (Becton Dickinson) band pass filter. Fluorescence (FL1) was detected with a 620 (±60)-nm band-pass filter (Gesellschaft für dünne Schichten mbH; Hugo Anders, Nabburg, Germany). FAM-labeled probes were excited with the 488-nm line of the argon ion laser at an output power of 500 mW. FSC was then detected through a BP 488/10 (Becton Dickinson) band-pass filter, and FL1 was detected through a BP 530/30 band-pass filter.

The system threshold was usually set on FSC. FAM-labeled probes were measured with 1× PBS (pH 9.0), and CY3- and TAMRA-labeled probes were measured with deionized water as sheath fluid. Polychromatic, 0.5-μm polystyrene beads (Polysciences, Warrington, Pa.) were used to check the stability of the optical alignment of the flow cytometer and to standardize the fluorescence intensities of cells hybridized with CY3-labeled probes. For quantification of cells hybridized with FAM-labeled probes, 0.5-μm yellow-green polystyrene beads were used.

Data acquisition and processing.

The parameters FSC and FL1 were recorded as pulse height signals (4 decades in logarithmic scale each), and for each measurement 10,000 events were stored in list mode files. Subsequent analysis was done with the CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Probe-conferred fluorescence was determined as the median of the FL1 values of single cells recorded in a gate that was defined in an FSC-versus-FL1 dot plot. Fluorescence of cells was corrected by subtraction of background fluorescence of negative controls and standardized to the fluorescence of reference beads. All values were finally expressed relative to the value for the brightest probe detected.

Probe-conferred fluorescence intensities were recorded for triplicate samples. Each replicate represents independent cell hybridization. Only triplicates with a coefficient of variation of less than 10% were accepted; otherwise, the quantification was repeated. The mean of triplicate measurements is given in Table 1.

Comparison of 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA.

A total of 13 probes were chosen to compare 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA accessibilities, with six probes targeting the 16S rRNA and seven targeting the 23S rRNA. The former were taken from the study of Fuchs and colleagues (6). Since the 16S rRNA was previously screened with FAM-labeled oligonucleotides and the 23S rRNA in this study was screened with CY3-labeled probes, probe batches labeled with FAM and CY3 and additionally with a third dye, TAMRA, were quantified. All probes were hybridized against the same E. coli batch, and all fluorescence intensities were standardized to the fluorescence of the brightest probe on the 16S rRNA, Eco1482.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

23S rRNA accessibility.

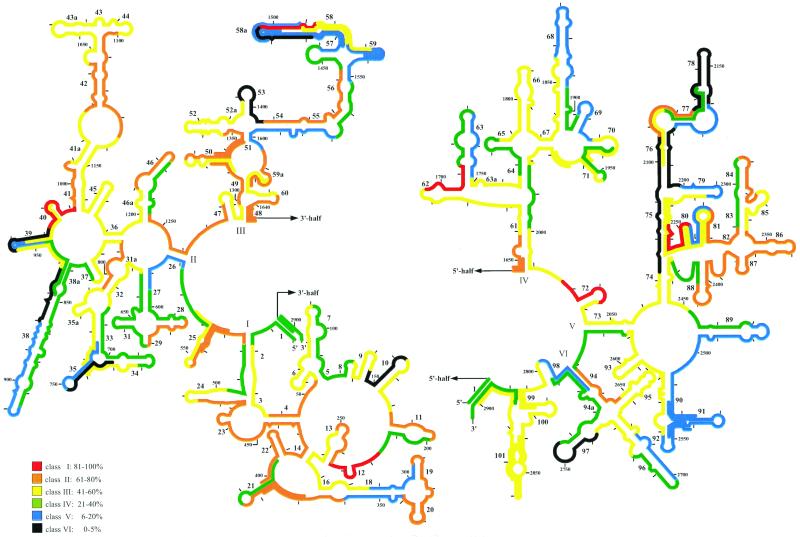

The brightest signal after hybridization to the 23S rRNA on E. coli was recorded for probe 23S-2018 binding to positions 2018 to 2035 (5). Consequently, fluorescence intensities from all probes were expressed as a percentage of that of 23S-2018 and grouped into six brightness classes (Table 1). Class I probes showed 100 to 81% of the 23S-2018 probe's fluorescence, class II showed 80 to 61%, class III showed 60 to 41%, class IV showed 40 to 21%, class V showed 20 to 6%, and class VI showed 5 to 0% (6). An additional five probes yielded signal intensities of class I: 23S-218 (81%), 23S-974 (94%), 23S-1497 (83%), 23S-1696 (94%), and 23S-2236 (81%) (Fig. 1). More than half of the probes tested fell in classes II and III. They targeted coherent areas, e.g., between helices 2 and 7, 13 and 16, 19 and 24, 31a and 32, 41 and 46, 47 and 52, 54 and 56, 59 and 62, 66 and 67, 72 and 74, 84 and 88, 92 and 93, 94 and 95, and 99 and 101 (Fig. 1). About a third of the probes quantified had medium (class IV) (33 probes) to low (class V) (30 probes) accessibility on the 23S ribosomal RNA. Most clustered, e.g., around helix 31, the long helix 38, between helices 54 and 59, at helices 63, 68, and 69, in the area encompassing helices 89 to 92, and at helix 96. The rest were spread over the 23S rRNA molecule (Fig. 1). Twelve probes yielded signals hardly above background levels (relative fluorescence, 0 to 5%). These highly inaccessible sites are at helices 10, 35, 38, 38, 53, 58, 75, 76, 78, and 97 (Fig. 1). Hybridization of these class VI probes at 37 and 41°C did not enhance the probe-conferred signals (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Fluorescence intensities of all oligonucleotide probes, standardized to that of the brightest probe, 23S-2018, shown in a 23S rRNA secondary structure model (7). The 5′ and the 3′ halves of the 23S rRNA are depicted on the left and right, respectively. The color coding indicates differences in the level of probe-conferred fluorescence. Additional probes for a detailed analysis of four regions with steep changes in accessibility are included in the graphs.

Fine mapping.

Four regions showing steep changes in accessibility were examined at a higher spatial resolution with additional probes (Fig. 1; Table 1). The class III probe 23S-939, with a relative fluorescence of 49%, is surrounded by the class VI probes 23S-921 (relative fluorescence, 3%) and 23S-956 (4%). The latter is directly adjacent to one of the brightest probes, 23S-974 (94%). Three additional probes that targeted intermediate sites showed fluorescence intensities between the extreme values: for 23S-930, 37%; for 23S-948, 14%; and for probe 23S-965, 51% relative fluorescence.

A similar situation is found between positions 2090 and 2143. There, the class II probe 23S-2108 (relative fluorescence, 63%) is flanked by two sites with low accessibility (23-2090 and 23S-2126, both at 3%). The fine mapping with probes 23S-2099 and 23S-2117 revealed intermediate accessibilities of 41 and 22%, respectively. In the third region examined, the bright probes 23S-2236 (81%) and 23S-2272 (75%) frame the dim probe 23S-2254 (10%). All three probes used for fine resolution of this area, 23S-2227 (48%), 23S-2245 (60%), and 23S-2263 (47%), are class III. Finally, a very steep increase in accessibility could be detected at helix 58a. The 5′ end of helix 58 and 58a is targeted by four probes (23S-1467, 23S-1479, 23S-1485, and 23S-1491) with a maximal relative fluorescence of 9% (23S-1491). The adjacent probe 23S-1497 showed high accessibility (83%). When the target site was moved further towards the 3′ end of the 23S rRNA, the signals dropped again to a class III (23S-1509, 45%, and 23S-1515, 56%) and finally to a class V (23S-1524, 6%, and 23S-1533, 15%) level at the 3′ end of helix 58.

Current structure models of the large subunit of the ribosome, such as the probably most elaborate model, the 2.4-Å-resolution crystal structure for Haloarcula marismortui (4) or the 7.5-Å cryo-electron microscopic reconstruction for E. coli (9), provide some possible explanations for sites with low accessibility. The helices 38, 39, and 89, all of which show class V accessibility, are apparently at least partly involved in tight bonds to the 5S ribosomal RNA (see reference 9 and references therein). Interactions with ribosomal proteins may be responsible for the low signals as well, e.g., the interaction of protein L1 with the distal part of helix 68, probes 23S-2117 and 23S-2162 (9). The ribosomal protein L6 presumably causes low levels of fluorescence at the distal part of helix 89. Other parts of the 23S rRNA, such as the helices 75 and 76, are located deeper within the 50S subunit. The respective probes may be hindered in penetrating to the target site. However, the accessibility data presented in our study were obtained on fixed E. coli cells, and therefore attempts to correlate probe accessibility with structural data should be done with great care.

Comparison of 16S and 23S rRNA accessibility.

At first glance, the 23S rRNA is more accessible to oligonucleotide probes than the 16S rRNA in the small subunit of the ribosome. Almost 60% of all probes quantified could be grouped in the brightness classes I to III, compared to only 39% on the 16S rRNA. Vice versa, only 23% of the 23S rRNA probes belonged to class V or VI, whereas 32% of probes targeting the 16S rRNA show relatively low binding. However, it must be considered that the study on the in situ accessibility of the 16S rRNA of E. coli was performed with a FAM-labeled oligonucleotide probe, whereas the present study used CY3-labeled probes. CY3 is currently the most-used label in FISH, since it has a high absorption coefficient and a high quantum yield, shows little bleaching and, in contrast to FAM, is pH insensitive. Even though CY3 is a stronger fluorophor than FAM, relative fluorescence values should not be influenced by the change of label.

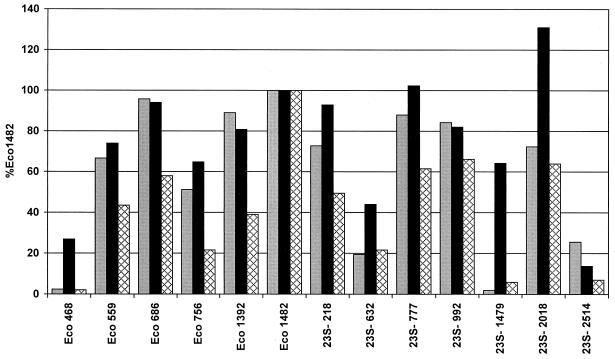

To nevertheless investigate a potential influence of the fluorescent marker on relative probe binding, a comparison of FAM, CY3, and additionally TAMRA was done with a set of oligonucleotides encompassing 16S and 23S rRNA-targeted probes of different brightness classes. Quantification of the FAM-labeled probes (Fig. 2) showed that Eco1482 was the brightest probe among all probes measured. The FAM-labeled 16S rRNA-targeted probes Eco686 (96%) and Eco1392 (89%) were still brighter than the brightest FAM-labeled probe targeting 23S rRNA, 23S-777 (88%). The lowest fluorescence intensities, with 2% relative fluorescence each, were found for probes Eco468 on the 16S rRNA and 23S-1479 on the 23S rRNA. For TAMRA-labeled probes the picture was similar. The brightest signals could be obtained from Eco1482, followed by 23S-992 (66%), 23S-2018 (64%), and 23S-777 (62%). Probes Eco468 (2%) and 23S-1479 (6%) once again were associated with low accessibility. The CY3-labeled probes, however, generally showed higher relative fluorescence than the FAM- and TAMRA-labeled oligonucleotides. With CY3 as the label, the brightest 23S rRNA-targeted probe, 23S-2018 (131%), showed a higher fluorescence intensity than Eco1482, the brightest probe with FAM and TAMRA, on which all fluorescence values were normalized. Furthermore, probes Eco486, 23S-1479, and 23S-632 showed considerably better relative binding when labeled with CY3 than with FAM and TAMRA (Fig. 2). Apparently there is a link between the type of label and accessibility. The explanation for this phenomenon may be the more linear chemical structure of the carbocyanine dye CY3 compared to those of the two-dimensional triphenylmethane dyes FAM and TAMRA. A one-dimensional dye molecule might penetrate better into the tight higher-order structure of the ribosome (4). Fluorophor-dependent quenching at the various target sites and differences in the charging or charge distributions of the different dye molecules may be alternative explanations. We have recently started a study on the in situ accessibility of the 16S rRNA of E. coli for CY3-labeled oligonucleotide probes to further investigate this phenomenon in comparison to the earlier data of Fuchs and colleagues (6).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of 16S and 23S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes, labeled with FAM (gray bars), CY3 (black bars), and TAMRA (cross-hatched bars). All fluorescence intensities are calibrated to that of the respectively labeled probe Eco1482.

We also investigated whether the accessibility of 23S rRNA target sites is linked to their mean phylogenetic conservation. The coefficient r2 was found to be 3.7%. Obviously, as previously shown for the 16S rRNA, there is no significant correlation between these two properties (6) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Correlation of the conservation value and relative fluorescence intensity of each probe measured in the study. Conservation values were calculated by averaging the conservation values of single nucleotide positions comprising the probe target position. The conservation values are based on the fraction of available bacterial sequences that share an identical nucleotide in a particular alignment position (ARB software; Department of Microbiology, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany [http://www.mikro.biologie.tu-muenchen.de]). They are expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.), in which low values indicate low evolutionary conservation.

Conclusions.

The 23S rRNA has twice as many potential probe target sites as the 16S rRNA, for which it is sometimes difficult to find diagnostic sequences unique to a chosen group of organisms. It has been pointed out (1) that even in cases where a 16S rRNA-targeted probe can still be designed, a 23S rRNA-targeted probe of similar or identical specificity is valuable in increasing the significance of in situ identification. Due to the high evolutionary conservation of this molecule, the 23S rRNA in situ accessibility map for E. coli can, within certain limits, as previously discussed for the 16S rRNA (6), be extrapolated to other microorganisms. We hope that this study supports a more intensive use of the 23S rRNA as a target for FISH in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Am 73/3-1 and the Max Planck Society.

We thank Nenad Ban and Pavel Baranov for helpful discussions on the structure of the 23S rRNA and Jörg Wulf and Daniela Lange for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R, Ludwig W. Typing in situ with probes. In: Priest F G, Ramos-Cormenzana A, Tindall B J, editors. Bacterial diversity and systematics. New York, N.Y: Plenum; 1994. pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Krumholz L, Stahl D A. Fluorescent-oligonucleotide probing of whole cells for determinative, phylogenetic, and environmental studies in microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:762–770. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.762-770.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ban N, Nissen P, Hansen J, Moore P B, Steitz T A. The complete atomic structure of the large ribosomal subunit at 2.4 angstrom resolution. Science. 2000;289:905–920. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brosius J, Dull T J, Sleeter D D, Noller H F. Gene organization and primary structure of a ribosomal RNA operon from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:107–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs B M, Wallner G, Beisker W, Schwippl I, Ludwig W, Amann R. Flow cytometric analysis of the in situ accessibility of Escherichia coli 16S rRNA for fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4973–4982. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4973-4982.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutell R R, Larsen N, Woese C R. Lessons from an evolving rRNA: 16S and 23S structures from a comparative perspective. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:10–26. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.10-26.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maidak B L, Cole J R, Lilburn T G, Parker C T J, Saxmann P R, Stredwick J M, Garrity G M, Olsen G J, Pramanik S, Schmidt T M, Tiedje J M. The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) continues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:173–174. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller F, Sommer I, Baranov P, Matadeen R, Stoldt M, Wohnert J, Gorlach M, van Heel M, Brimacombe R. The 3D arrangement of the 23 S and 5 S rRNA in the Escherichia coli 50 S ribosomal subunit based on a cryo-electron microscopic reconstruction at 7.5 angstrom resolution. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:35–59. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen G J, Lane D J, Giovannoni S J, Pace N R, Stahl D A. Microbial ecology and evolution: a ribosomal rRNA approach. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1986;40:337–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.40.100186.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suggs S V, Hirose T, Miyake T, Kawashima E H, Johnson M J, Itakura K, Wallace R B. Use of synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotides for the isolation of specific cloned DNA sequences. In: Brown D, Fox C F, editors. Developmental biology using purified genes. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1981. pp. 683–693. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallner G, Fuchs B, Spring S, Beisker W, Amann R. Flow sorting of microorganisms for molecular analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4223–4231. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4223-4231.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woese C R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]