Abstract

The inactive X chromosome (Xi) serves as a model to understand gene silencing on a global scale. Here, we perform “identification of direct RNA interacting proteins” (iDRiP) to isolate a comprehensive protein interactome for Xist, an RNA required for Xi silencing. We discover multiple classes of interactors, including cohesins, condensins, topoisomerases, RNA helicases, chromatin remodelers and modifiers, which synergistically repress Xi transcription. Inhibiting two or three interactors destabilizes silencing. While Xist attracts some interactors, it repels architectural factors. Xist evicts cohesins from the Xi and directs an Xi-specific chromosome conformation. Upon deleting Xist, the Xi acquires the cohesin-binding and chromosomal architecture of the active X. Our study unveils many layers of Xi repression and demonstrates a central role for RNA in the topological organization of mammalian chromosomes.

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian X chromosome is unique in its ability to undergo whole-chromosome silencing. In the early female embryo, X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) enables mammals to achieve gene dosage equivalence between the XX female and the XY male (1–3). XCI depends on Xist RNA, a 17-kb long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) expressed only from the inactive X-chromosome (Xi)(4) and that implements silencing by recruiting repressive complexes (5–8). While XCI initiates only once during development, the female mammal stably maintains the Xi through her lifetime. In mice, a germline deletion of Xist results in peri-implantation lethality due to a failure of Xi establishment (9), whereas a lineage-specific deletion of Xist causes a lethal blood cancer due to a failure of Xi maintenance (10). Thus, both the de novo establishment and proper maintenance of the Xi are crucial for viability and homeostasis. There are therefore two critical phases of XCI: (i) A one-time initiation phase in peri-implantation embryonic development that is recapitulated by differentiating embryonic stem [ES] cells in culture, and (ii) a lifelong maintenance phase that persists in all somatic lineages.

Once established, the Xi is extremely stable and difficult to disrupt genetically and pharmacologically (11–13). In mice, X-reactivation is programmed to occur only twice — once in the blastocyst to erase the imprinted XCI pattern and a second time in the germline prior to meiosis (14, 15). Although the Xi's epigenetic stability is a homeostatic asset, an ability to unlock this epigenetic state is of great current interest. The X-chromosome is home to nearly 1000 genes, at least 50 of which have been implicated in X-linked diseases, such as Rett syndrome and Fragile X syndrome. The Xi is therefore a reservoir of functional genes that could be tapped to replace expression of a disease allele on the active X (Xa). A better understanding of Xi repression would inform both basic biological mechanisms and treatment of X-linked diseases.

It is believed that Xist RNA silences the Xi through conjugate protein partners. A major gap in current understanding is the lack of a comprehensive Xist interactome. In spite of multiple attempts to define the complete interactome, only four directly interacting partners have been identified over the past two decades, including PRC2, ATRX, YY1, and HNRPU: Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) is targeted by Xist RNA to the Xi; the ATRX RNA helicase is required for the specific association between Xist and PRC2 (16, 17); YY1 tethers the Xist-PRC2 complex to the Xi nucleation center (18); and the nuclear matrix factor, HNRPU/SAF-A, enables stable association of Xist with the chromosomal territory (19). Many additional interacting partners are expected, given the large size of Xist RNA and its numerous conserved modular domains. Here, we develop a new RNA-based proteomic method and implement an unbiased screen for Xist's comprehensive interactome. We identify a large number of high-confidence candidates, demonstrate that it is possible to destabilize Xi repression by inhibiting multiple interacting components, and then delve into a focused set of interactors with the cohesins.

RESULTS

iDRiP identifies multiple classes of Xist-interacting proteins

A systematic identification of interacting factors has been challenging because of Xist's large size, the expected complexity of the interactome, and the persistent problem of high background with existing biochemical approaches (20). A high background could be particularly problematic for chemical crosslinkers that create extensive covalent networks of proteins, which could in turn mask specific and direct interactions. We therefore developed iDRiP (identification of direct RNA interacting proteins) using the zero-length crosslinker, UV light, to implement an unbiased screen of directly interacting proteins in female mouse fibroblasts expressing physiological levels of Xist RNA (Fig. 1A). We performed in vivo UV crosslinking, prepared nuclei, and solubilized chromatin by DNase I digestion. Xist-specific complexes were captured using 9 complementary oligonucleotide probes spaced across the 17-kb RNA, with each probe being 25-nt length to maximize RNA capture while reducing non-specific hybridization. The complexes were then washed under denaturing conditions to eliminate factors that were not covalently linked by UV to Xist RNA. To minimize background due to DNA-bound proteins, a key step was inclusion of DNase I treatment before elution of complexes (See Supplemental Discussion). We observed significant enrichment of Xist RNA over highly abundant cytoplasmic and nuclear RNAs (U6, Jpx, 18S rRNA) in eluates of female fibroblasts (Fig. 1B). Enrichment was not observed in male eluates or with luciferase capture probes. Eluted proteins were subjected to quantitative mass spectrometry (MS), with spectral counting (21) and multiplexed quantitative proteomics (22) yielding similar enrichment sets (Table S1).

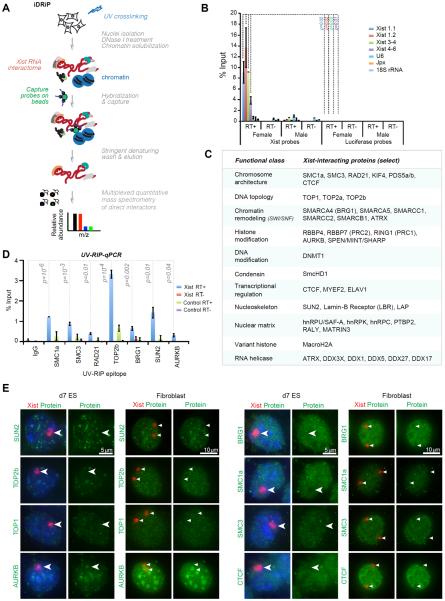

Figure 1. iDRiP-MS reveals a large Xist interactome.

(A) iDRiP schematic.

(B) RT-qPCR demonstrated the specificity of Xist pulldown by iDRiP. Xist and control luciferase probes were used for pulldown from UV-crosslinked female and control male fibroblasts. Efficiency of Xist pulldown was calculated by comparing to a standard curve generated using 10-fold dilutions of input. Mean ± standard error (SE) of three independent experiments shown. P values determined by the Student t-test.

(C) Select high-confidence candidates from three biological replicates are grouped into functional classes. Additional candidates shown in Table S1.

(D) UV-RIP-qPCR validation of candidate interactors. Enrichment calculated as % input, as in (B). Mean ± SE of three independent experiments shown. P values determined by the Student t-test.

(E) RNA immunoFISH to examine localization of candidate interactors (green) in relation to Xist RNA (red). Immortalized MEF cells are tetraploid and harbor two Xi.

From three independent replicates, iDRiP-MS revealed a large Xist protein interactome (Fig. 1C; Table S1). Recovery of known Xist interactors, PRC2, ATRX, and HNRPU, provided a first validation of the iDRiP technique. Also recovered were macrohistone H2A (mH2A), RING1 (PRC1), and the condensin component, SmcHD1 — proteins known to be enriched on the Xi (23, 24, 19), but not previously shown to interact directly. More than 80 proteins were found to be ≥3-fold enriched over background; more than 200 proteins were ≥2-fold enriched (Table S1). Called on the basis of enrichment values and follow-up validations, novel high-confidence interactors fell into several functional categories: (i) Cohesin complex proteins, SMC1a, SMC3, RAD21, KIF4, PDS5a/b, as well as CTCF (25), which are collectively implicated in chromosome looping (26–28); (ii) histone modifiers such as aurora kinase B (AURKB), a serine/threonine kinase that phosphorylates histone H3 (29); RING1, the catalytic subunit of Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) for H2A-K119 ubiquitylation (23); and MINT/SPEN/RBM15/SHARP, which associates with HDACs; (iii) SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling factors; (iv) topoisomerases, TOP2a, TOP2b, and TOP1, that relieve torsional stress during transcription and DNA replication; (v) miscellaneous transcriptional regulators, MYEF2 and ELAV1; (vi) nucleoskeletal proteins that anchor chromosomes to the nuclear envelope, SUN2, Lamin-B receptor (LBR), and LAP2; (vii) nuclear matrix proteins, hnRPU/SAF-A, hnRPK, and MATRIN3; and (viii) the DNA methyltransferase, DNMT1, known as a maintenance methylase for CpG dinucleotides (30). In many cases (e.g., cohesins, SWI/SNF), multiple subunits of the epigenetic complex were identified, boosting our confidence in them as interactors. Because of stringent denaturing washes, non-crosslinked subunits of identified complexes were also of interest. We verified the interactions by performing a test of reciprocity: By using candidate proteins as bait in a RIP-qPCR of UV-crosslinked cells, we similarly detected the RNA-protein interaction (Fig. 1D).

To study their function, we first performed RNA immunoFISH of female cells and observed several patterns of Xi coverage relative to the surrounding nucleoplasm (Fig. 1E). Like PRC2, RING1 (PRC1) has been shown to be enriched on the Xi (23) and is therefore not pursued further. TOP1 and TOP2a/b appeared neither enriched nor depleted on the Xi (100%, n>50 nuclei). AURKB showed two patterns of localization — peri-centric enrichment (20%, n>50) and a more diffuse localization pattern (80%, data now shown), consistent with its cell-cycle dependent chromosomal localization (29). On the other hand, while SUN2 was depleted on the Xi (100%, n=52), it often appeared as pinpoints around the Xi in both day 7 differentiating female ES cells (establishment phase; 44%, n=307) and in fibroblasts (maintenance phase; 38.5%, n=52), consistent with SUN2's function in tethering telomeres to the nuclear envelope. Finally, the cohesins and SWI/SNF remodelers showed an unexpected “hole” or depletion relative to the surrounding nucleoplasm (100%, n=50–100). These patterns suggest that the Xist interactors operate in different XCI pathways.

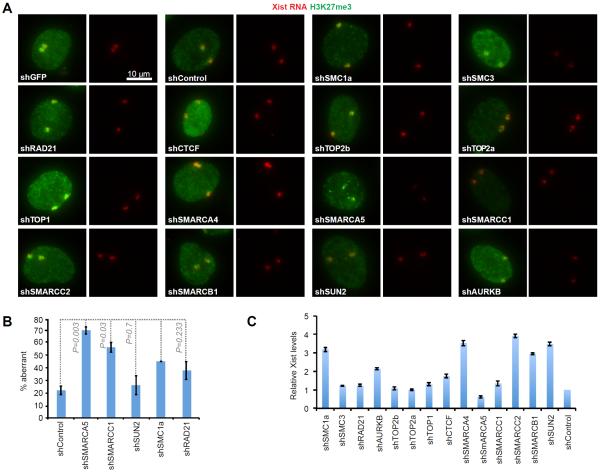

To ask if the factors intersect the PRC2 pathway, we stably knocked down (KD) top candidates using shRNAs (Table S2) and performed RNA immunoFISH to examine trimethylation of histone H3-lysine 27 (H3K27me3; Fig. 2A,B). No major changes to Xist localization or H3K27me3 were evident in d7 ES cells (Fig. S1). There were, however, long-term effects in fibroblasts: The decreased in H3K27me3 enrichment in shSMARCC1 and shSMARCA5 cells (Fig. 2A,B) indicated that SWI/SNF interaction with Xist is required for proper maintenance of PRC2 function on the Xi. Steady state Xist levels did not change by more than 2-fold (Fig. 2C) and were therefore unlikely to be the cause of the Polycomb defect. Knockdowns of other factors (cohesins, topoisomerases, SUN2, AURKB) had no obvious effects on Xist localization and H3K27me3. Thus, whereas the SWI/SNF factors intersect the PRC2 pathway, other interactors do not overtly impact PRC2.

Figure 2. Impact of depleting Xist interactors on H3K27me3.

(A) RNA immunoFISH of Xist (red) and H3K27me3 (green) after shRNA KD of interactors in fibroblasts (tetraploid; 2 Xist clouds). KD efficiencies (fraction remaining): SMC1a-0.48, SMC3-0.39, RAD21-0.15, AURKB-0.27, TOP2b-0.20, TOP2a-0.42, TOP1-0.34, CTCF-0.62, SMARCA4-0.52, SMARCA5-0.18, SMARCC1-0.25, SMARCC2-0.32, SMARCB1-0.52 and SUN2-0.72. Some factors are essential; therefore, high percentage KD may be inviable. All images presented at the same photographic exposure and contrast.

(B) Quantitation of RNA immunoFISH results. n, sample size. % aberrant Xist/H3K27me3 associations shown.

(C) RT-qPCR of Xist levels in KD fibroblasts, normalized to shControls. Mean± SD of two independent experiments shown.

Xi-reactivation via targeted inhibition of three interactors

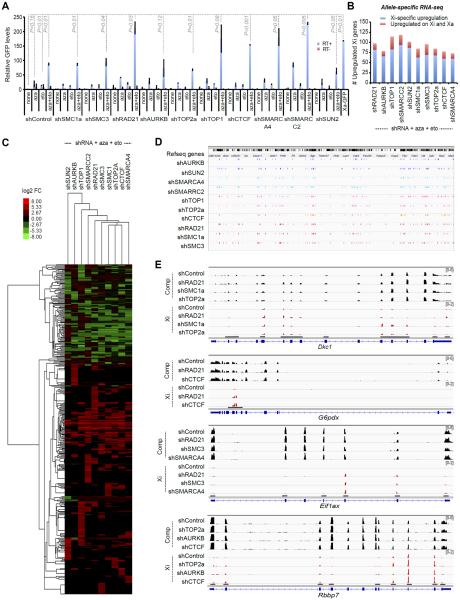

Given the large number of interactors, we created a screen to analyze effects on Xi gene expression. We derived clonal fibroblast lines harboring a transgenic GFP reporter on the Xi (Fig. S2) and shRNAs against Xist interactors. Knockdown of any one interactor did not reactivate GFP by more than 4-fold (Fig. 3A, shControl+none; Fig. S3A). Suspecting synergistic repression, we targeted multiple pathways using a combination drugs. To target DNMT1, we employed the small molecule, 5'-azacytidine (aza)(30) at a nontoxic concentration of 0.3 μM (≤IC50) which minimally reactivated GFP (Fig. 3A, shControl + aza). To target TOP2a/b (31), we employed etoposide (eto) at 0.3 μM (≤IC50), which also minimally reactivated GFP (Fig. 3A, shControl + eto). Combining 0.3 μM aza + eto led to an 80- to 90-fold reactivation — a level that was almost half of GFP levels on the Xa (Xa-GFP, Fig. 3A), suggesting strong synergy between DNMT1 and TOP2 inhibitors. Using aza + eto as priming agents, we designed triple-drug combinations inclusive of shRNAs for proteins that have no specific small molecule inhibitors. In various shRNA + aza + eto combinations, we achieved up to 230-fold GFP reactivation — levels that equaled or exceeded Xa-GFP levels (Fig. 3A). Greatest effects were observed for combinations using shSMARCC2 (227x), shSMARCA4 (180x), and shRAD21 (211x). shTOP1 and shCTCF were also effective (175x, 154x). Combinations involving remaining interactors yielded 63x to 94x reactivation.

Figure 3. De-repression of Xi genes by targeting Xist interactors.

(A) Relative GFP levels by RT-qPCR analysis in female fibroblasts stably knocked down for indicated interactors ± 0.3 μM 5'-azacytidine (aza) ± 0.3 μM etoposide (eto). Xa-GFP, control male fibroblasts with X-linked GFP. Mean ± SE of two independent experiments shown. P, determined by Student t-test.

(B) Allele-specific RNA-seq analysis: Number of upregulated Xi genes for each indicated triple-drug treatment (aza+eto+shRNA). Blue, genes specifically reactivated on Xi (fold-change, FC>2); red, genes also unregulated on Xa (FC>1.3).

(C) RNA-seq heat map indicating that a large number of genes on the Xi were reactivated. X-linked genes reactivated in at least one of the triple-drug treatment (aza+eto+shRNA) were shown in the heat map. Color key, Log2 fold-change (FC). Cluster analysis performed based on similarity of KD profiles (across) and on the sensitivity and selectivity of various genes to reactivation (down).

(D) Chromosomal locations of Xi reactivated genes (colored ticks) for various aza+eto+shRNA combinations.

(E) Read coverage of 4 reactivated Xi genes after triple-drug treatment. Xi, mus reads (scale: 0–2). Comp, total reads (scale: 0–6). Red tags appear only in exons with SNPs.

We then performed allele-specific RNA-seq to investigate native Xi genes. In an F1 hybrid fibroblast line in which the Xi is of Mus musculus (mus) origin and the Xa of Mus casteneus (cas) origin, >600,000 X-linked sequence polymorphisms enabled allele-specific calls (32). Two biological replicates of each of the most promising triple-drug treatments showed good correlation (Fig. S4–S6). RNA-seq analysis showed reactivation of 75–100 Xi-specific genes in one replicate (Fig. 3B) and up to 200 in a second replicate (Fig. S3B), representing a large fraction of expressed X-linked genes, considering that only ~210 X-linked genes have an FPKM≥1.0 in this hybrid fibroblast line. Heatmap analysis demonstrated that, for individual Xi genes, reactivation levels ranged from 2x–80x for various combinatorial treatments (Fig. 3C). There was a net increase in expression level (ΔFPKM) from the Xi in the triple-drug treated samples relative to the shControl+aza+eto, whereas the Xa and autosomes showed no obvious net increase, thereby suggesting direct effects on the Xi as a result of disrupting the Xist interactome. Reactivation was not specific to any one Xi region (Fig. 3D). Most effective were shRAD21, shSMC3, shSMC1a, shSMARCA4, shTOP2a, and shAURKB drug combinations. Genic examination confirmed increased representation of mus-specific tags (red) relative to the shControl (Fig. 3E). Such allelic effects were not observed at imprinted loci and other autosomal genes (Fig. S7), further suggesting Xi-specific allelic effects. The set of reactivated genes varied among drug treatments, though some genes (Rbbp7, G6pdx, Fmr1, etc.) appeared more prone to reactivation. Thus, the Xi is maintained by multiple synergistic pathways and Xi genes can be reactivated by targeted inhibition of three distinct Xist interactors.

Xist interaction leads to cohesin repulsion

To investigate mechanism, we focused on one group of interactors — the cohesins — because they are implicated in establishing chromosomal architecture and their knockdowns destabilized Xi repression (Fig. 3). To obtain Xa and Xi binding patterns, we performed allele-specific ChIP-seq for two cohesin subunits, SMC1a and RAD21, and for CTCF, which works together with cohesins (33, 34, 28, 35). In wildtype cells, CTCF binding was enriched on Xa (cas), but also showed a number of Xi (mus)-specific sites (Fig. 4A)(36, 25). Allelic ratios ranged from equal to nearly complete Xa or Xi skewing (Fig. 4A). For the cohesins, 1490 SMC1a and 871 RAD21 binding sites were mapped onto ChrX in total, of which allelic calls could be made on ~50% of sites (Fig. 4B,C). While the Xa and Xi each showed significant cohesin binding, Xa-specific greatly outnumbered Xi-specific sites. For SMC1a, 717 sites were called on Xa, of which 589 were Xa-specific; 203 sites were called on Xi, of which 20 were Xi-specific. For RAD21, 476 sites were called on Xa, of which 336 were Xa-specific; 162 sites were called on Xi, of which 18 were Xi-specific. Biological replicates showed similar trends (Fig. S8A,B).

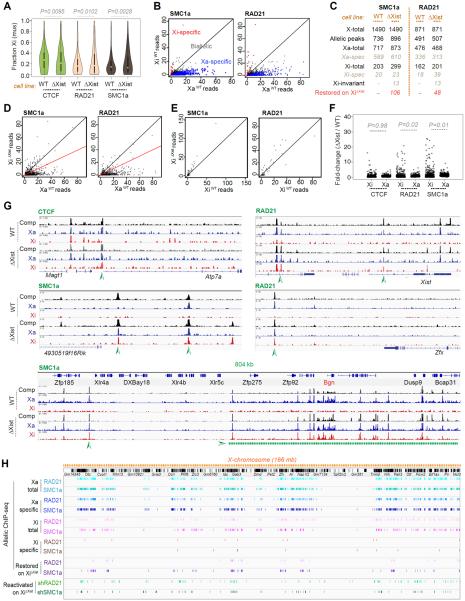

Figure 4. Ablating Xist in cis restores cohesin binding on the Xi.

(A) Allele-specific ChIP-seq results: Violin plots of allelic skew for CTCF, RAD21, SMC1a in wild-type (WT) and XiΔXist/XaWT (ΔXist) fibroblasts. Fraction of mus reads [mus/(mus+cas)] is plotted for every peak with ≥10 allelic reads. P values determined by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test.

(B) Differences between SMC1a or RAD21 peaks on the XiWT versus XaWT. Black diagonal, 1:1 ratio. Plotted are read counts for all SMC1a or RAD21 peaks. Allele-specific skewing is defined as ≥3-fold skew towards either Xa (cas, blue dots) or Xi (mus, red dots). Biallelic peaks, grey dots.

(C) Table of total, Xa-specific, and Xi-specific cohesin binding sites in WT versus ΔXist (XiΔXist/XaWT) cells. Significant SMC1a and RAD21 allelic peaks with ≥5 reads were analyzed. Allele-specific skewing is defined as ≥3-fold skew towards Xa or Xi. Sites were considered “restored” if XiΔXist's read counts were ≥50% of Xa's. X-total, all X-linked binding sites. Allelic peaks, sites with allelic information. Xa-total, all Xa sites. Xi-total, all sites. Xa-spec, Xa-specific. Xi-spec, Xi-specific. Xi-invariant, Xi-specific in both WT and XiΔXist/XaWT cells. Note: There is a net gain of 96 sites on the Xi in the mutant, a number different from the number of restored sites (106). This difference is due to defining restored peaks separately from calling ChIP peaks (macs2). Allele-specific skewing is defined as ≥3-fold skew towards either Xa or Xi.

(D) Partial restoration of SMC1a or RAD21 peaks on the XiΔXist to an Xa pattern. Plotted are peaks with read counts with ≥3-fold skew to XaWT (“Xa-specific”). x-axis, normalized XaWT read counts. y-axis, normalized XiΔXist read counts. Black diagonal, 1:1 XiΔXist/XaWT ratio; red diagonal, 1:2 ratio.

(E) Xi-specific SMC1a or RAD21 peaks remained on XiΔXist. Plotted are read counts for SMC1a or RAD21 peaks with ≥3-fold skew to XiWT (“Xi-specific”).

(F) Comparison of fold-changes for CTCF, RAD21, and SMC1 binding in XΔXist cells relative to WT cells. Shown are fold-changes for Xi versus Xa. The Xi showed significant gains in RAD21 and SMC1a binding, but not in CTCF binding. Method: XWT and XΔXist ChIP samples were normalized by scaling to equal read counts. Fold-changes for Xi were computed by dividing the normalized mus read count in XΔXist by the mus read count XWT; fold-changes for Xa were computed by dividing the normalized cas read count in XΔXist by the cas read count XWT. To eliminate noise, peaks with <10 allelic reads were eliminated from analysis. P values determined by a paired Wilcoxon signed rank test.

(G) The representative examples of cohesion restoration on XiΔXist. Arrowheads, restored peaks.

(H) Allelic-specific cohesin binding profiles of Xa, XiWT, and XiΔXist. Shown below restored sites are regions of Xi-reactivation following shSMC1a and shRAD21 triple-drug treatments, as defined in Figure 3.

Cohesin's Xa preference was unexpected in light of Xist's physical interaction with cohesins, which suggested that Xist might attract cohesins to the Xi. We therefore conditionally ablated Xist from the Xi (XiΔXist) and repeated ChIP-seq analysis in the XiΔXist/XaWT fibroblasts (37). Surprisingly, XiΔXist acquired 106 SMC1a and 48 RAD21 sites in cis, at positions that were previously Xa-specific (Fig. 4C,D). Biological replicates trended similarly (Fig. S8–S9). In nearly all cases, acquired sites represented a restoration of Xa sites, rather than binding to random positions. By contrast, sites that were previously Xi-specific remained intact (Fig. 4C,E, S8B), suggesting that they do not require Xist for either recruitment or maintenance. The changes in cohesin peak densities were Xi-specific and significant (Fig. 4F). Cohesin restoration occurred throughout XiΔXist, resulting in domains of biallelic binding (Fig. 4G,S10–S12), and often favored regions that harbor genes that escape XCI (e.g., Bgn)(38, 39). There were also shifts in CTCF binding, more noticeable at a locus-specific level than at a chromosomal level (Fig. 4A,G), suggesting that CTCF and cohesins do not necessarily track together on the Xi. The observed dynamics were ChrX-specific and were not observed on autosomes (Fig. S13). To determine whether there were restoration hotspots, we plotted restored SMC1a and RAD21 sites (Fig. 4H; purple) on XiΔXist and observed clustering within gene-rich regions. We conclude that Xist does not recruit cohesins to the Xi-specific sites. Instead, Xist actively repels cohesins in cis to prevent establishment of the Xa pattern.

Xist RNA directs an Xi-specific chromosome conformation

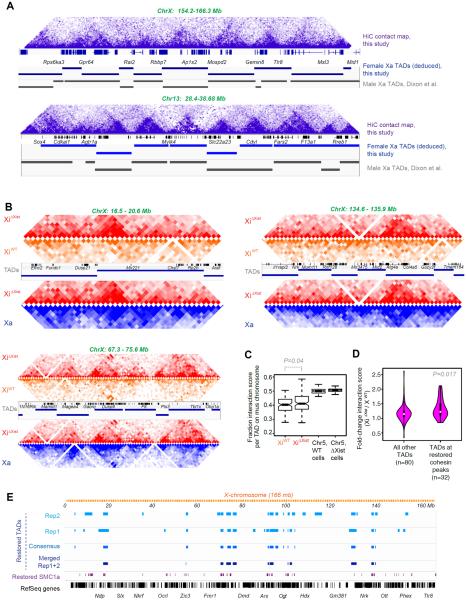

Cohesins and CTCF have been shown to facilitate formation of large chromosomal domains called TADs (topologically associated domains)(27, 40, 34, 28, 35, 41, 42). The function of TADs is currently not understood, as TADs are largely invariant across development. However, X-linked TADs are exceptions to this rule and are therefore compelling models to study their function (43–46). By carrying out allele-specific HiC-seq, we asked whether cohesin restoration altered the chromosomal architecture of XiΔXist. First, we observed that, in wildtype cells, our TADs called on autosomal contact maps at 40-kb resolution resembled published composite (non-allelic) maps (27)(Fig. 5A, bottom). Our ChrX contact maps were also consistent, with TADs being less distinct due to a summation of Xa and Xi reads in the non-allelic (composite) profiles (Fig. 5A, top). Using the 44% of reads with allelic information, our allelic analysis yielded high-quality contact maps at 100-kb resolution by combining replicates (Fig. 5B) or at 200-kb resolution with a single replicate (Fig. S14). In wildtype cells, we deduced 112 TADs at 40-kb resolution on ChrX using the method of Dixon et al.(27). We attempted TAD calling for the Xi on the 100 kb contact map, but were unable to obtain obvious TAD, suggesting the 112 TADs are present only on the Xa. Thus, while the Xa is topologically organized into structured domains, the Xi is devoid of such organization across its full length.

Figure 5. Ablating Xist results in Xi reversion to an Xa-like chromosome conformation.

(A) Chr13 and ChrX contact maps showing triangular domains representative of TADs. Purple shades correspond to varying interaction frequencies (dark, greater interactions). TADs called from our composite (non-allelic) HiC data at 40-kb resolution (blue bars) are highly similar to those (gray bars) called previously (27).

(B) Allele-specific HiC-seq analysis: Contact maps for three different ChrX regions at 100-kb resolution comparing XiΔXist (red) to XiWT (orange), and XiΔXist (red) versus Xa (blue) of the mutant cell line. Our Xa TAD calls are shown with RefSeq genes.

(C) Fraction of interaction frequency per TAD on the Xi (mus) chromosome. The positions of our Xa TAD borders were rounded to the nearest 100 kb and submatrices were generated from all pixels between the two endpoints of the TAD border for each TAD. We calculated the average interaction score for each TAD by summing the interaction scores for all pixels in the submatrix defined by a TAD and dividing by the total number of pixels in the TAD. We then averaged the normalized interaction scores across all bins in a TAD in the Xi (mus) and Xa (cas) contact maps, and computed the fraction of averaged interaction scores from mus chromosomes. ChrX and a representative autosome, Chr5, are shown for the WT cell line and the XistΔXist/+ cell line. P value determined by paired Wilcoxon signed rank test.

(D) Violin plots showing that TADs overlapping restored peaks have larger increases in interaction scores relative to all other TADs. We calculated the fold-change in average interaction scores on the Xi for all X-linked TADs and intersected the TADs with SMC1a sites (XiΔXist/ XiWT). 32 TADs occurred at restored cohesin sites; 80 TADs did not overlap restored cohesin sites. Violin plot shows distributions of fold-change average interaction scores between XiWT and XiΔXist. p-value deteremined by Wilcoxon ranked sum test.

(E) Restored TADs overlap regions with restored cohesins on across XiΔXist. Several datasets were used to call restored TADs, each producing similar results. Restored TADs were called in two separate replicates (Rep1, Rep2) where the average interaction score was signficantly higher on XiΔXist than on XiWT. We also called restored TADs based on merged Rep1+Rep2 datasets. Finally, a consensus between Rep1 and Rep2 was derived. Method: We calculated the fold-change in mus or cas for all TADs on ChrX and on a control, Chr5; then defined a threshold for significant changes based on either the autosomes or the Xa. We treated Chr5 as a null distribution (few changes expected on autosomes) and found the fraction of TADs that crossed the threshold for several thesholds. These fractions corresponded to a false discovery rate (FDR) for each given threshold. An FDR of 0.05 was used.

When Xist was ablated, however, TADs were restored in cis and the Xi reverted to an Xa-like conformation (Fig. 5B, S14). In mutant cells, ~30 TADs were gained on XiΔXist in each biological replicate. Where TADs were restored, XiΔXist patterns (red) became nearly identical to those of the Xa (blue), with similar interaction frequencies. These XiΔXist regions now bore little resemblance to the Xi of wildtype cells (XiWT, orange). Overall, the difference in the average interaction scores between XiWT and XiΔXist was highly significant (Fig. 5C, S15A). Intersecting TADs with SMC1a sites on XiΔXist revealed that 61 restored cohesin sites overlapped restored TADs (61 did not overlap). TADs overlapping restored peaks had larger increases in interaction scores relative to all other TADs (Fig. 5D,S15B) and we observed an excellent correlation between the restored cohesin sites and the restored TADs (Fig. 5E,S15C), consistent with a role of cohesins in re-establishing TADs following Xist deletion. Taken together, these data uncover a role for RNA in establishing topological domains of mammalian chromosomes and demonstrate that Xist must actively and continually repulse cohesins from the Xi, even during the maintenance phase, to prevent formation of an Xa chromosomal architecture.

DISCUSSION

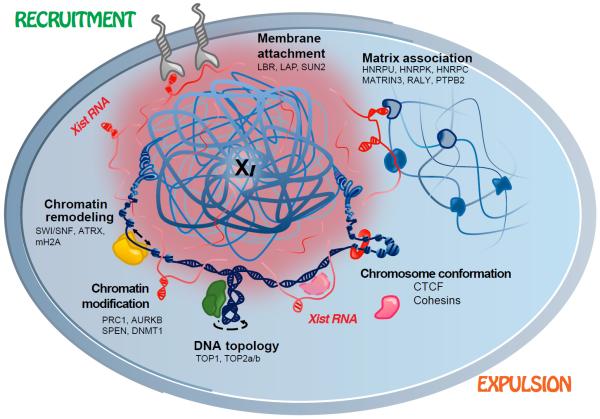

Using iDRiP, we have identified a comprehensive Xist interactome and revealed multiple synergistic pathways to Xi repression (Fig. 6). With Xist physically contacting 80–250 proteins at any given time, the Xist ribonucleoprotein particle may be as large as the ribosome. Xist RNA, however, does not only serve as scaffold. Indeed, Xist actively recruits and repels chromatin regulatory proteins. For repressive factors such as PRC1, PRC2, ATRX, mH2A, and SmcHD1, Xist binding results in recruitment to the Xi (23, 24, 16, 17). For architectural factors such as the cohesins, Xist binding leads to repulsion from the Xi. Repulsion could be based on eviction, with Xist releasing cohesins as it repels them, or on sequestration, with Xist sheltering cohesins to prevent Xi binding. Our study shows that the Xi harbors two types of cohesin sites: (i) those recruited to and/or maintained on the Xi independently of Xist, and (ii) those that reappear on Xi only when Xist is ablated. The two classes of cohesin sites likely explain the paradoxical observations that, on the one hand, depleting cohesins leads to Xi reactivation but, on the other, loss of Xist-mediated cohesin recruitment leads to an Xa-like chromosome conformation that is permissive for transcription. In essence, modulating the Type i and Type ii sites both have the effect of destabilizing the Xi, rendering the Xi more accessible to transcription. Disrupting Type i sites by cohesin knockdown would change the repressive Xi structure; ablating Xist would restore the Type ii sites that promote an Xa-like conformation. Our study has focused on cohesins, but RNA-mediated repulsion may be an outcome for other Xist interactors and may be as prevalent an epigenetic mechanism as RNA-mediated recruitment (47).

Figure 6. The Xi is suppressed by multiple synergistic mechanisms.

Xist RNA (red) suppresses the Xi by either recruiting repressive factors (e.g., PRC1, PRC2) or expelling architectural factors (e.g., cohesins).

The robustness of Xi silencing is demonstrated by the observation that we destabilized the Xi only after pharmacologically targeting three distinct pathways, and not by inhibiting just one factor. The fact that the triple-drug treatments varied with respect to reactivated loci and depth of de-repression creates the possibility of treating X-linked disease in a locus-specific manner by administering unique drug combinations. Given the existence of many other disease-associated lncRNAs, the iDRiP technique could be applied systematically towards identifying new drug targets for other diseases and generally for elucidating mechanisms of epigenetic regulation by lncRNA.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank S. Gygi for access to computational resources for proteomic analysis and all members of the Lee and Haas laboratories for valuable discussions. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01-DA-38695, R03-MH97478), the Rett Syndrome Research Trust, and the International Rett Syndrome Foundation to J.T.L.; and a National Science Foundation predoctoral award to J.F. J.T.L. is an Investigator of the HHMI.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Starmer J, Magnuson T. Development. 2009;136:1. doi: 10.1242/dev.025908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Disteche CM. Annual review of genetics. 2012;46:537. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wutz A, Agrelo R. Dev Cell. 2012;23:680. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown CJ, et al. Cell. 1992;71:527. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90520-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, et al. Nat Genet. 2001;28:371. doi: 10.1038/ng574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohlmaier A, et al. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plath K, et al. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:1025. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao J, et al. Molecular cell. 2010;40:939. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marahrens Y, Panning B, Dausman J, Strauss W, Jaenisch R. Genes Dev. 1997;11:156. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yildirim E, et al. Cell. 2013;152:727. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown CJ, Willard HF. Nature. 1994;368:154. doi: 10.1038/368154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Csankovszki G, Nagy A, Jaenisch R. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:773. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatnagar S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413620111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mak W, et al. Science. 2004;303:666. doi: 10.1126/science.1092674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugimoto M, Abe K. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao J, Sun BK, Erwin JA, Song JJ, Lee JT. Science. 2008;322:750. doi: 10.1126/science.1163045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarma K, et al. Cell. 2014;159:869. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeon Y, Lee JT. Cell. 2011;146:119. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasegawa Y, et al. Dev Cell. 2010;19:469. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wutz A. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:542. doi: 10.1038/nrg3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundgren DH, Hwang SI, Wu L, Han DK. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2010;7:39. doi: 10.1586/epr.09.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ting L, Rad R, Gygi SP, Haas W. Nat Methods. 2011;8:937. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoeftner S, et al. The EMBO journal. 2006;25:3110. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blewitt ME, et al. Nat Genet. 2008;40:663. doi: 10.1038/ng.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kung JT, et al. Molecular cell. 2015;57:361. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagey MH, et al. Nature. 2010;467:430. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dixon JR, et al. Nature. 2012;485:376. doi: 10.1038/nature11082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merkenschlager M, Odom DT. Cell. 2013;152:1285. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall LL, Byron M, Pageau G, Lawrence JB. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:491. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh V, Sharma P, Capalash N. Current cancer drug targets. 2013;13:379. doi: 10.2174/15680096113139990077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashour ME, Atteya R, El-Khamisy SF. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2015;15:137. doi: 10.1038/nrc3892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinter SF, et al. Genome Res. 2012;22:1864. doi: 10.1101/gr.133751.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin S, Ferguson-Smith AC, Schultz RM, Bartolomei MS. Molecular and cellular biology. 2011;31:3094. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01449-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, et al. Nature. 2013;498:516. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dowen JM, et al. Cell. 2014;159:374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calabrese JM, et al. Cell. 2012;151:951. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang LF, Huynh KD, Lee JT. Cell. 2007;129:693. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carrel L, Willard HF. Nature. 2005;434:400. doi: 10.1038/nature03479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berletch JB, Yang F, Xu J, Carrel L, Disteche CM. Human genetics. 2011;130:237. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1011-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feig C, Odom DT. The EMBO journal. 2013;32:3114. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ong CT, Corces VG. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:234. doi: 10.1038/nrg3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vietri Rudan M, et al. Cell reports. 2015;10:1297. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Splinter E, et al. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1371. doi: 10.1101/gad.633311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nora EP, et al. Nature. 2012;485:381. doi: 10.1038/nature11049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagano T, et al. Nature. 2013;502:59. doi: 10.1038/nature12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rao SS, et al. Cell. 2014;159:1665. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun S, et al. Cell. 2013;153:1537. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.