Abstract

Motivation: The enormous amount of short reads generated by the new DNA sequencing technologies call for the development of fast and accurate read alignment programs. A first generation of hash table-based methods has been developed, including MAQ, which is accurate, feature rich and fast enough to align short reads from a single individual. However, MAQ does not support gapped alignment for single-end reads, which makes it unsuitable for alignment of longer reads where indels may occur frequently. The speed of MAQ is also a concern when the alignment is scaled up to the resequencing of hundreds of individuals.

Results: We implemented Burrows-Wheeler Alignment tool (BWA), a new read alignment package that is based on backward search with Burrows–Wheeler Transform (BWT), to efficiently align short sequencing reads against a large reference sequence such as the human genome, allowing mismatches and gaps. BWA supports both base space reads, e.g. from Illumina sequencing machines, and color space reads from AB SOLiD machines. Evaluations on both simulated and real data suggest that BWA is ∼10–20× faster than MAQ, while achieving similar accuracy. In addition, BWA outputs alignment in the new standard SAM (Sequence Alignment/Map) format. Variant calling and other downstream analyses after the alignment can be achieved with the open source SAMtools software package.

Availability: http://maq.sourceforge.net

Contact: rd@sanger.ac.uk

1 INTRODUCTION

The Illumina/Solexa sequencing technology typically produces 50–200 million 32–100 bp reads on a single run of the machine. Mapping this large volume of short reads to a genome as large as human poses a great challenge to the existing sequence alignment programs. To meet the requirement of efficient and accurate short read mapping, many new alignment programs have been developed. Some of these, such as Eland (Cox, 2007, unpublished material), RMAP (Smith et al., 2008), MAQ (Li et al., 2008a), ZOOM (Lin et al., 2008), SeqMap (Jiang and Wong, 2008), CloudBurst (Schatz, 2009) and SHRiMP (http://compbio.cs.toronto.edu/shrimp), work by hashing the read sequences and scan through the reference sequence. Programs in this category usually have flexible memory footprint, but may have the overhead of scanning the whole genome when few reads are aligned. The second category of software, including SOAPv1 (Li et al., 2008b), PASS (Campagna et al., 2009), MOM (Eaves and Gao, 2009), ProbeMatch (Jung Kim et al., 2009), NovoAlign (http://www.novocraft.com), ReSEQ (http://code.google.com/p/re-seq), Mosaik (http://bioinformatics.bc.edu/marthlab/Mosaik) and BFAST (http://genome.ucla.edu/bfast), hash the genome. These programs can be easily parallelized with multi-threading, but they usually require large memory to build an index for the human genome. In addition, the iterative strategy frequently introduced by these software may make their speed sensitive to the sequencing error rate. The third category includes slider (Malhis et al., 2009) which does alignment by merge-sorting the reference subsequences and read sequences.

Recently, the theory on string matching using Burrows–Wheeler Transform (BWT) (Burrows and Wheeler, 1994) has drawn the attention of several groups, which has led to the development of SOAPv2 (http://soap.genomics.org.cn/), Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009) and BWA, our new aligner described in this article. Essentially, using backward search (Ferragina and Manzini, 2000; Lippert, 2005) with BWT, we are able to effectively mimic the top-down traversal on the prefix trie of the genome with relatively small memory footprint (Lam et al., 2008) and to count the number of exact hits of a string of length m in O(m) time independent of the size of the genome. For inexact search, BWA samples from the implicit prefix trie the distinct substrings that are less than k edit distance away from the query read. Because exact repeats are collapsed on one path on the prefix trie, we do not need to align the reads against each copy of the repeat. This is the main reason why BWT-based algorithms are efficient.

In this article, we will give a sufficient introduction to the background of BWT and backward search for exact matching, and present the algorithm for inexact matching which is implemented in BWA. We evaluate the performance of BWA on simulated data by comparing the BWA alignment with the true alignment from the simulation, as well as on real paired-end data by checking the fraction of reads mapped in consistent pairs and by counting misaligned reads mapped against a hybrid genome.

2 METHODS

2.1 Prefix trie and string matching

The prefix trie for string X is a tree where each edge is labeled with a symbol and the string concatenation of the edge symbols on the path from a leaf to the root gives a unique prefix of X. On the prefix trie, the string concatenation of the edge symbols from a node to the root gives a unique substring of X, called the string represented by the node. Note that the prefix trie of X is identical to the suffix trie of reverse of X and therefore suffix trie theories can also be applied to prefix trie.

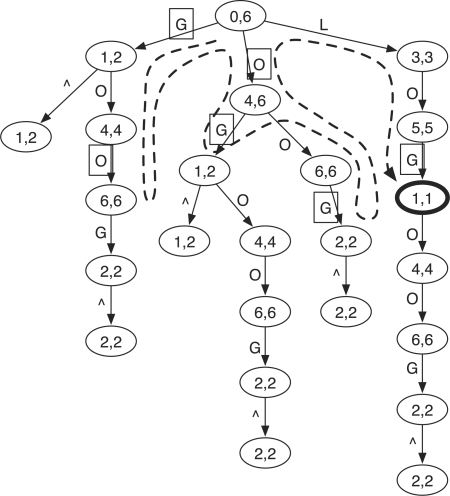

With the prefix trie, testing whether a query W is an exact substring of X is equivalent to finding the node that represents W, which can be done in O(|W|) time by matching each symbol in W to an edge, starting from the root. To allow mismatches, we can exhaustively traverse the trie and match W to each possible path. We will later show how to accelerate this search by using prefix information of W. Figure 1 gives an example of the prefix trie for ‘GOOGOL’. The suffix array (SA) interval in each node is explained in Section 2.3.

Fig. 1.

Prefix trie of string ‘GOOGOL’. Symbol ∧ marks the start of the string. The two numbers in a node give the SA interval of the string represented by the node (see Section 2.3). The dashed line shows the route of the brute-force search for a query string ‘LOL’, allowing at most one mismatch. Edge labels in squares mark the mismatches to the query in searching. The only hit is the bold node [1, 1] which represents string ‘GOL’.

2.2 Burrows–Wheeler transform

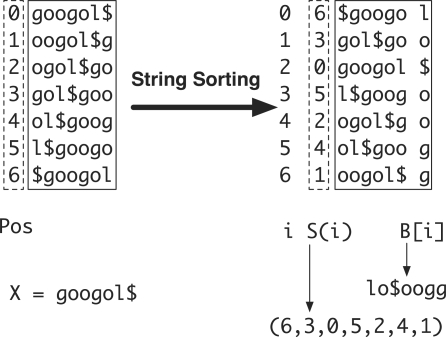

Let Σ be an alphabet. Symbol $ is not present in Σ and is lexicographically smaller than all the symbols in Σ. A string X=a0a1…an−1 is always ended with symbol $ (i.e. an−1=$) and this symbol only appears at the end. Let X[i]=ai, i=0, 1,…, n−1, be the i-th symbol of X, X[i, j]=ai …aj a substring and Xi=X[i, n−1] a suffix of X. Suffix array S of X is a permutation of the integers 0…n−1 such that S(i) is the start position of the i-th smallest suffix. The BWT of X is defined as B[i]=$ when S(i)=0 and B[i]=X[S(i)−1] otherwise. We also define the length of string X as |X| and therefore |X|=|B|=n. Figure 2 gives an example on how to construct BWT and suffix array.

Fig. 2.

Constructing suffix array and BWT string for X=googol$. String X is circulated to generate seven strings, which are then lexicographically sorted. After sorting, the positions of the first symbols form the suffix array (6, 3, 0, 5, 2, 4, 1) and the concatenation of the last symbols of the circulated strings gives the BWT string lo$oogg.

The algorithm shown in Figure 2 is quadratic in time and space. However, this is not necessary. In practice, we usually construct the suffix array first and then generate BWT. Most algorithms for constructing suffix array require at least n⌈log2n⌉ bits of working space, which amounts to 12 GB for human genome. Recently, Hon et al. (2007) gave a new algorithm that uses n bits of working space and only requires <1 GB memory at peak time for constructing the BWT of human genome . This algorithm is implemented in BWT-SW (Lam et al., 2008). We adapted its source code to make it work with BWA.

2.3 Suffix array interval and sequence alignment

If string W is a substring of X, the position of each occurrence of W in X will occur in an interval in the suffix array. This is because all the suffixes that have W as prefix are sorted together. Based on this observation, we define:

| (1) |

| (2) |

In particular, if W is an empty string, R(W)=1 and  . The interval

. The interval  is called the SA interval of W and the set of positions of all occurrences of W in X is

is called the SA interval of W and the set of positions of all occurrences of W in X is  . For example in Figure 2, the SA interval of string ‘go’ is [1, 2]. The suffix array values in this interval are 3 and 0 which give the positions of all the occurrences of ‘go’.

. For example in Figure 2, the SA interval of string ‘go’ is [1, 2]. The suffix array values in this interval are 3 and 0 which give the positions of all the occurrences of ‘go’.

Knowing the intervals in suffix array we can get the positions. Therefore, sequence alignment is equivalent to searching for the SA intervals of substrings of X that match the query. For the exact matching problem, we can find only one such interval; for the inexact matching problem, there may be many.

2.4 Exact matching: backward search

Let C(a) be the number of symbols in X[0, n−2] that are lexicographically smaller than a ∈ Σ and O(a, i) the number of occurrences of a in B[0, i]. Ferragina and Manzini (2000) proved that if W is a substring of X:

| (3) |

| (4) |

and that  if and only if aW is a substring of X. This result makes it possible to test whether W is a substring of X and to count the occurrences of W in O(|W|) time by iteratively calculating R and

if and only if aW is a substring of X. This result makes it possible to test whether W is a substring of X and to count the occurrences of W in O(|W|) time by iteratively calculating R and  from the end of W. This procedure is called backward search.

from the end of W. This procedure is called backward search.

It is important to note that Equations (3) and (4) actually realize the top-down traversal on the prefix trie of X given that we can calculate the SA interval of a child node in constant time if we know the interval of its parent. In this sense, backward search is equivalent to exact string matching on the prefix trie, but without explicitly putting the trie in the memory.

2.5 Inexact matching: bounded traversal/backtracking

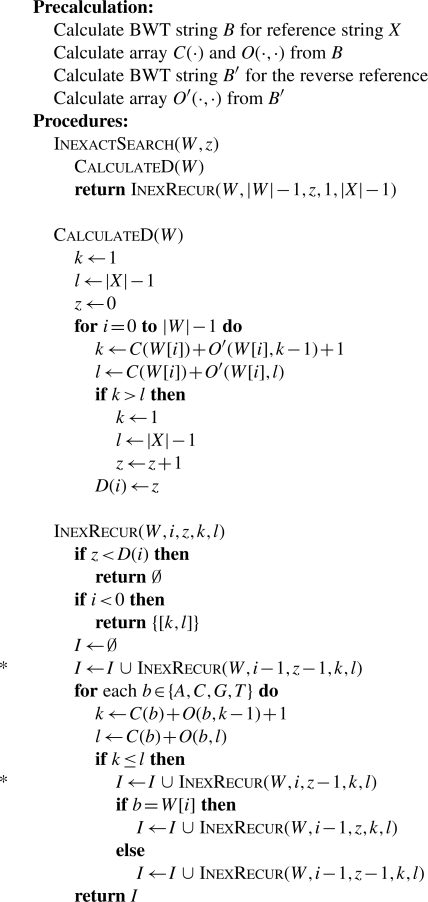

Figure 3 gives a recursive algorithm to search for the SA intervals of substrings of X that match the query string W with no more than z differences (mismatches or gaps). Essentially, this algorithm uses backward search to sample distinct substrings from the genome. This process is bounded by the D(·) array where D(i) is the lower bound of the number of differences in W[0, i]. The better the D is estimated, the smaller the search space and the more efficient the algorithm is. A naive bound is achieved by setting D(i)=0 for all i, but the resulting algorithm is clearly exponential in the number of differences and would be less efficient.

Fig. 3.

Algorithm for inexact search of SA intervals of substrings that match W. Reference X is $ terminated, while W is A/C/G/T terminated. Procedure InexactSearch(W, z) returns the SA intervals of substrings that match W with no more than z differences (mismatches or gaps); InexRecur(W, i, z, k, l) recursively calculates the SA intervals of substrings that match W[0, i] with no more than z differences on the condition that suffix Wi+1 matches interval [k, l]. Lines started with asterisk are for insertions to and deletions from X, respectively. D(i) is the lower bound of the number of differences in string W[0, i].

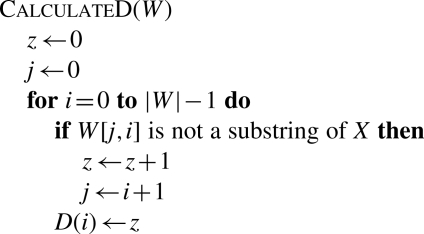

The CalculateD procedure in Figure 3 gives a better, though not optimal, bound. It is conceptually equivalent to the one described in Figure 4, which is simpler to understand. We use the BWT of the reverse (not complemented) reference sequence to test if a substring of W is also a substring of X. Note that to do this test with BWT string B alone would make CalculateD an O(|W|2) procedure, rather than O(|W|) as is described in Figure 3.

Fig. 4.

Equivalent algorithm to calculate D(i).

To understand the role of D, we come back to the example of searching for W =LOL in X=GOOGOL$ (Fig. 1). If we set D(i)=0 for all i and disallow gaps (removing the two star lines in the algorithm), the call graph of InexRecur, which is a tree, effectively mimics the search route shown as the dashed line in Figure 1. However, with CalculateD, we know that D(0)=0 and D(1)=D(2)=1. We can then avoid descending into the ‘G’ and ‘O’ subtrees in the prefix trie to get a much smaller search space.

The algorithm in Figure 3 guarantees to find all the intervals allowing maximum z differences. It is complete in theory, but in practice, we also made various modifications. First, we pay different penalties for mismatches, gap opens and gap extensions, which is more realistic to biological data. Second, we use a heap-like data structure to keep partial hits rather than using recursion. The heap-like structure is prioritized on the alignment score of the partial hits to make BWA always find the best intervals first. The reverse complemented read sequence is processed at the same time. Note that the recursion described in Figure 3 effectively mimics a depth-first search (DFS) on the prefix trie, while BWA implements a breadth-first search (BFS) using this heap-like data structure. Third, we adopt an iterative strategy: if the top interval is repetitive, we do not search for suboptimal intervals by default; if the top interval is unique and has z difference, we only search for hits with up to z + 1 differences. This iterative strategy accelerates BWA while retaining the ability to generate mapping quality. However, this also makes BWA's speed sensitive to the mismatch rate between the reads and the reference because finding hits with more differences is usually slower. Fourth, we allow to set a limit on the maximum allowed differences in the first few tens of base pairs on a read, which we call the seed sequence. Given 70 bp simulated reads, alignment with maximum two differences in the 32 bp seed is 2.5× faster than without seeding. The alignment error rate, which is the fraction of wrong alignments out of confident mappings in simulation (see also Section 3.2), only increases from 0.08% to 0.11%. Seeding is less effective for shorter reads.

2.6 Reducing memory

The algorithm described above needs to load the occurrence array O and the suffix array S in the memory. Holding the full O and S arrays requires huge memory. Fortunately, we can reduce the memory by only storing a small fraction of the O and S arrays, and calculating the rest on the fly. BWT-SW (Lam et al., 2008) and Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009) use a similar strategy which was first introduced by Ferragina and Manzini (2000).

Given a genome of size n, the occurrence array O(·, ·) requires 4n⌈log2n⌉ bits as each integer takes ⌈log2n⌉ bits and there are 4n of them in the array. In practice, we store in memory O(·, k) for k that is a factor of 128 and calculate the rest of elements using the BWT string B. When we use two bits to represent a nucleotide, B takes 2n bits. The memory for backward search is thus 2n+n⌈log2n⌉/32 bits. As we also need to store the BWT of the reverse genome to calculate the bound, the memory required for calculating intervals is doubled, or about 2.3 GB for a 3 Gb genome.

Enumerating the position of each occurrence requires the suffix array S. If we put the entire S in memory, it would use n⌈log2n⌉ bits. However, it is also possible to reconstruct the entire S when knowing part of it. In fact, S and inverse compressed suffix array (inverse CSA) Ψ−1 (Grossi and Vitter, 2000) satisfy:

| (5) |

where (Ψ−1)(j) denotes repeatedly applying the transform Ψ−1 for j times. The inverse CSA Ψ−1 can be calculated with the occurrence array O:

| (6) |

In BWA, we only store in memory S(k) for k that can be divided by 32. For k that is not a factor of 32, we repeatedly apply Ψ−1 until for some j, (Ψ−1)(j)(k) is a factor of 32 and then S((Ψ−1)(j)(k)) can be looked up and S(k) can be calculated with Equation (5).

In all, the alignment procedure uses 4n+n⌈log2n⌉/8 bits, or n bytes for genomes <4 Gb. This includes the memory for the BWT string, partial occurrence array and partial suffix array for both original and the reversed genome. Additionally, a few hundred megabyte of memory is required for heap, cache and other data structures.

2.7 Other practical concerns for Illumina reads

2.7.1 Ambiguous bases

Non-A/C/G/T bases on reads are simply treated as mismatches, which is implicit in the algorithm (Fig. 3). Non-A/C/G/T bases on the reference genome are converted to random nucleotides. Doing so may lead to false hits to regions full of ambiguous bases. Fortunately, the chance that this may happen is very small given relatively long reads. We tried 2 million 32 bp reads and did not see any reads mapped to poly-N regions by chance.

2.7.2 Paired-end mapping

BWA supports paired-end mapping. It first finds the positions of all the good hits, sorts them according to the chromosomal coordinates and then does a linear scan through all the potential hits to pair the two ends. Calculating all the chromosomal coordinates requires to look up the suffix array frequently. This pairing process is time consuming as generating the full suffix array on the fly with the method described above is expensive. To accelerate pairing, we cache large intervals. This strategy halves the time spent on pairing.

In pairing, BWA processes 256K read pairs in a batch. In each batch, BWA loads the full BWA index into memory, generates the chromosomal coordinate for each occurrence, estimates the insert size distribution from read pairs with both ends mapped with mapping quality higher than 20, and then pairs them. After that, BWA clears the BWT index from the memory, loads the 2 bit encoded reference sequence and performs Smith–Waterman alignment for unmapped reads whose mates can be reliably aligned. Smith–Waterman alignment rescues some reads with excessive differences.

2.7.3 Determining the allowed maximum number of differences

Given a read of length m, BWA only tolerates a hit with at most k differences (mismatches or gaps), where k is chosen such that <4% of m-long reads with 2% uniform base error rate may contain differences more than k. With this configuration, for 15–37 bp reads, k equals 2; for 38–63 bp, k=3; for 64–92 bp, k=4; for 93–123 bp, k=5; and for 124–156 bp reads, k=6.

2.7.4 Generating mapping quality scores

For each alignment, BWA calculates a mapping quality score, which is the Phred-scaled probability of the alignment being incorrect. The algorithm is similar to MAQ's except that in BWA we assume the true hit can always be found. We made this modification because we are aware that MAQ's formula overestimates the probability of missing the true hit, which leads to underestimated mapping quality. Simulation reveals that BWA may overestimate mapping quality due to this modification, but the deviation is relatively small. For example, BWA wrongly aligns 11 reads out of 1 569 108 simulated 70 bp reads mapped with mapping quality 60. The error rate 7 × 10−6 (= 11/1 569 108) for these Q60 mappings is higher than the theoretical expectation 10−6.

2.8 Mapping SOLiD reads

For SOLiD reads, BWA converts the reference genome to dinucleotide ‘color’ sequence and builds the BWT index for the color genome. Reads are mapped in the color space where the reverse complement of a sequence is the same as the reverse, because the complement of a color is itself. For SOLiD paired-end mapping, a read pair is said to be in the correct orientation if either of the two scenarios is true: (i) both ends mapped to the forward strand of the genome with the R3 read having smaller coordinate; and (ii) both ends mapped to the reverse strand of the genome with the F3 read having smaller coordinate. Smith–Waterman alignment is also done in the color space.

After the alignment, BWA decodes the color read sequences to the nucleotide sequences using dynamic programming. Given a nucleotide reference subsequence b1b2…bl+1 and a color read sequence c1c2…cl mapped to the subsequence, BWA infers a nucleotide sequence  such that it minimizes the following objective function:

such that it minimizes the following objective function:

where q′ is the Phred-scaled probability of a mutation, qi is the Phred quality of color ci and function g(b, b′)=g(b′, b) gives the color corresponding to the two adjacent nucleotides b and b′. Essentially, we pay a penalty q′ if  and a penalty qi if

and a penalty qi if  .

.

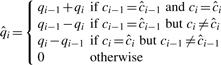

This optimization can be done by dynamic programming because the best decoding beyond position i only depends on the choice of  . Let

. Let  be the best decoding score up to i. The iteration equations are

be the best decoding score up to i. The iteration equations are

BWA approximates base qualities as follows. Let  . The i-th base quality

. The i-th base quality  , i=2…l, is calculated as:

, i=2…l, is calculated as:

|

BWA outputs the sequence  and the quality

and the quality  as the final result for SOLiD mapping.

as the final result for SOLiD mapping.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Implementation

We implemented BWA to do short read alignment based on the BWT of the reference genome. It performs gapped alignment for single-end reads, supports paired-end mapping, generates mapping quality and gives multiple hits if required. The default output alignment format is SAM (Sequence Alignment/Map format). Users can use SAMtools (http://samtools.sourceforge.net) to extract alignments in a region, merge/sort alignments, get single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and indel calls and visualize the alignment.

BWA is distributed under the GNU General Public License (GPL). Documentations and source code are freely available at the MAQ web site: http://maq.sourceforge.net.

3.2 Evaluated programs

To evaluate the performance of BWA, we tested additional three alignment programs: MAQ (Li et al., 2008a), SOAPv2 (http://soap.genomics.org.cn) and Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009). MAQ indexes reads with a hash table and scans through the genome. It is the software package we developed previously for large-scale read mapping. SOAPv2 and Bowtie are the other two BWT-based short read aligners that we are aware of. The latest SOAP-2.1.7 (Li et al., unpublished data) uses 2way-BWT (Lam et al., unpublished data) for alignment. It tolerates more mismatches beyond the 35 bp seed sequence and supports gapped alignment limited to one gap open. Bowtie (version 0.9.9.2) deploys a similar algorithm to BWA. Nonetheless, it does not reduce the search space by bounding the search with D(i), but by cleverly doing the alignment for both original and reverse read sequences to bypass unnecessary searches towards the root of the prefix trie. By default, Bowtie performs a DFS on the prefix trie and stops when the first qualified hit is found. Thus, it may miss the best inexact hit even if its seeding strategy is disabled. It is possible to make Bowtie perform a BFS by applying ‘–best’ at the command line, but this makes Bowtie slower. Bowtie does not support gapped alignment at the moment.

All the four programs, including BWA, randomly place a repetitive read across the multiple equally best positions. As we are mainly interested in confident mappings in practice, we need to rule out repetitive hits. SOAPv2 gives the number of equally best hits of a read. Only unique mappings are retained. We also ask SOAPv2 to limit the possible gap size to at most 3 bp. We run Bowtie with the command-line option ‘–best -k 2’, which renders Bowtie to output the top two hits of a read. We discard a read alignment if the second best hit contains the same number of mismatches as the best hit. MAQ and BWA generate mapping qualities. We use mapping quality threshold 1 for MAQ and 10 for BWA to determine confident mappings. We use different thresholds because we know that MAQ's mapping quality is underestimated, while BWA's is overestimated.

3.3 Evaluation on simulated data

We simulated reads from the human genome using the wgsim program that is included in the SAMtools package and ran the four programs to map the reads back to the human genome. As we know the exact coordinate of each read, we are able to calculate the alignment error rate.

Table 1 shows that BWA and MAQ achieve similar alignment accuracy. BWA is more accurate than Bowtie and SOAPv2 in terms of both the fraction of confidently mapped reads and the error rate of confident mappings. Note that SOAP-2.1.7 is optimized for reads longer than 35 bp. For the 32 bp reads, SOAP-2.0.1 outperforms the latest version.

Table 1.

Evaluation on simulated data

| Single-end |

Paired-end |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program | Time (s) | Conf (%) | Err (%) | Time (s) | Conf (%) | Err (%) |

| Bowtie-32 | 1271 | 79.0 | 0.76 | 1391 | 85.7 | 0.57 |

| BWA-32 | 823 | 80.6 | 0.30 | 1224 | 89.6 | 0.32 |

| MAQ-32 | 19797 | 81.0 | 0.14 | 21589 | 87.2 | 0.07 |

| SOAP2-32 | 256 | 78.6 | 1.16 | 1909 | 86.8 | 0.78 |

| Bowtie-70 | 1726 | 86.3 | 0.20 | 1580 | 90.7 | 0.43 |

| BWA-70 | 1599 | 90.7 | 0.12 | 1619 | 96.2 | 0.11 |

| MAQ-70 | 17928 | 91.0 | 0.13 | 19046 | 94.6 | 0.05 |

| SOAP2-70 | 317 | 90.3 | 0.39 | 708 | 94.5 | 0.34 |

| bowtie-125 | 1966 | 88.0 | 0.07 | 1701 | 91.0 | 0.37 |

| BWA-125 | 3021 | 93.0 | 0.05 | 3059 | 97.6 | 0.04 |

| MAQ-125 | 17506 | 92.7 | 0.08 | 19388 | 96.3 | 0.02 |

| SOAP2-125 | 555 | 91.5 | 0.17 | 1187 | 90.8 | 0.14 |

One million pairs of 32, 70 and 125 bp reads, respectively, were simulated from the human genome with 0.09% SNP mutation rate, 0.01% indel mutation rate and 2% uniform sequencing base error rate. The insert size of 32 bp reads is drawn from a normal distribution N(170, 25), and of 70 and 125 bp reads from N(500, 50). CPU time in seconds on a single core of a 2.5 GHz Xeon E5420 processor (Time), percent confidently mapped reads (Conf) and percent erroneous alignments out of confident mappings (Err) are shown in the table.

On speed, SOAPv2 is the fastest and actually it would be 30–80% faster for paired-end mapping if gapped alignment was disabled. Bowtie with the default option (data not shown) is several times faster than the current setting ‘–best -k 2’ on single-end mapping. However, the speed is gained at a great cost of accuracy. For example, with the default option, Bowtie can map the two million single-end 32 bp reads in 151 s, but 6.4% of confident mappings are wrong. This high alignment error rate may complicate the detection of structural variations and potentially affect SNP accuracy. Between BWA and MAQ, BWA is 6–18× faster, depending on the read length. MAQ's speed is not affected by read length because internally it treats all reads as 128 bp. It is possible to accelerate BWA by not checking suboptimal hits similar to what Bowtie and SOAPv2 are doing. However, calculating mapping quality would be impossible in this case and we believe generating proper mapping quality is useful to various downstream analyses such as the detection of structural variations.

On memory, SOAPv2 uses 5.4 GB. Both Bowtie and BWA uses 2.3 GB for single-end mapping and about 3 GB for paired-end, larger than MAQ's memory footprint 1 GB. However, the memory usage of all the three BWT-based aligners is independent of the number of reads to be aligned, while MAQ's is linear in it. In addition, all BWT-based aligners support multi-threading, which reduces the memory per CPU core on a multi-core computer. On modern computer servers, memory is not a practical concern with the BWT-based aligners.

3.4 Evaluation on real data

To assess the performance on real data, we downloaded about 12.2 million pairs of 51 bp reads from European Read Archive (AC:ERR000589). These reads were produced by Illumina for NA12750, a male included in the 1000 Genomes Project (http://www.1000genomes.org). Reads were mapped to the human genome NCBI build 36. Table 2 shows that almost all confident mappings from MAQ and BWA exist in consistent pairs although MAQ gives fewer confident alignments. A slower mode of BWA (no seeding; searching for suboptimal hits even if the top hit is a repeat) did even better. In that mode, BWA confidently mapped 89.2% of all reads in 6.3 hours with 99.2% of confident mappings in consistent pairs.

Table 2.

Evaluation on real data

| Program | Time (h) | Conf (%) | Paired (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bowtie | 5.2 | 84.4 | 96.3 |

| BWA | 4.0 | 88.9 | 98.8 |

| MAQ | 94.9 | 86.1 | 98.7 |

| SOAP2 | 3.4 | 88.3 | 97.5 |

The 12.2 million read pairs were mapped to the human genome. CPU time in hours on a single core of a 2.5 GHz Xeon E5420 processor (Time), percent confidently mapped reads (Conf) and percent confident mappings with the mates mapped in the correct orientation and within 300 bp (Paired), are shown in the table.

In this experiment, SOAPv2 would be twice as fast with both percent confident mapping (Conf) and percent paired (Paired) dropping by 1% if gapped alignment was disabled. In contrast, BWA is 1.4 times as fast when it performs ungapped alignment only. But even with BWT-based gapped alignment disabled, BWA is still able to recover many short indels with Smith–Waterman alignment given paired-end reads.

We also obtained the chicken genome sequence (version 2.1) and aligned these 12.2 million read pairs against a human–chicken hybrid reference sequence. The percent confident mappings is almost unchanged in comparison to the human-only alignment. As for the number of reads mapped to the chicken genome, Bowtie mapped 2640, BWA 2942, MAQ 3005 and SOAPv2 mapped 4531 reads to the wrong genome. If we consider that the chicken sequences take up one-quarter of the human–chicken hybrid reference, the alignment error rate for BWA is about 0.06% (=2942×4/12.2M/0.889). Note that such an estimate of the alignment error rate may be underestimated because wrongly aligned human reads tend to be related to repetitive sequences in human and to be mapped back to the human sequences. The estimate may also be overestimated due to the presence of highly conservative sequences and the incomplete assembly of human or misassembly of the chicken genome.

If we want fewer errors, the mapping quality generated by BWA and MAQ allows us to choose alignments of higher accuracy. If we increased the mapping quality threshold in determining a confident hit to 25 for BWA, 86.4% of reads could be aligned confidently with 1927 reads mapped to the chicken genome, outperforming Bowtie in terms of both percent confident mappings and the number of reads mapped to the wrong genome.

4 DISCUSSION

For short read alignment against the human reference genome, BWA is an order of magnitude faster than MAQ while achieving similar alignment accuracy. It supports gapped alignment for single-end reads, which is increasingly important when reads get longer and tend to contain indels. BWA outputs alignment in the SAM format to take the advantage of the downstream analyses implemented in SAMtools. BWA plus SAMtools provides most of functionality of the MAQ package with additional features.

In comparison to speed, memory and the number of mapped reads, alignment accuracy is much harder to evaluate on real data as we do not know the ground truth. In this article, we used three criteria for evaluating the accuracy of an aligner. The first criterion, which can only be evaluated with simulated data, is the combination of the number of confident mappings and the alignment error rate out of the confident mappings. Note that the number of confident mappings alone may not be a good criterion: we can map more at the cost of accuracy. The second criterion, which is the combination of the number of aligned reads and the number of reads mapped in consistent pairs, works on real data on the assumption that the mating information from the experiment is correct and that structural variations are rare. Although this criterion is related to the way an aligner defines pair ‘consistency’, in our experience it is highly informative if the pairing parameters are set correctly. The third criterion is the fraction of reads mapped to the wrong reference sequence if we intentionally add reference sequences from a diverged species.

Although in theory BWA works with arbitrarily long reads, its performance is degraded on long reads especially when the sequencing error rate is high. Furthermore, BWA always requires the full read to be aligned, from the first base to the last one (i.e. global with respect to reads), but longer reads are more likely to be interrupted by structural variations or misassemblies in the reference genome, which will fail BWA. For long reads, a possibly better solution would be to divide the read into multiple short fragments, align the fragments separately with the algorithm described above and then join the partial alignments to get the full alignment of the read.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Mark DePristo and Jared Maguire from the Broad Institute for their suggestions on standardizing the criteria for evaluating alignment programs, and to the three anonymous reviewers whose comments helped us to improve the manuscript. We also thank the members of the Durbin research group for the comments on the initial draft.

Funding: Wellcome Trust/077192/Z/05/Z.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Burrows M, Wheeler DJ. Technical report 124. Palo Alto, CA: Digital Equipment Corporation; 1994. A block-sorting lossless data compression algorithm. [Google Scholar]

- Campagna D, et al. PASS: a program to align short sequences. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:967–968. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves HL, Gao Y. MOM: maximum oligonucleotide mapping. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:969–970. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferragina P, Manzini G. Proceedings of the 41st Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS 2000) IEEE Computer Society; 2000. Opportunistic data structures with applications; pp. 390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Grossi R, Vitter JS. Proceedings on 32nd Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC 2000) ACM; 2000. Compressed suffix arrays and suffix trees with applications to text indexing and string matching; pp. 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Hon W.-K, et al. A space and time efficient algorithm for constructing compressed suffix arrays. Algorithmica. 2007;48:23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wong WH. SeqMap: mapping massive amount of oligonucleotides to the genome. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2395–2396. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Kim Y, et al. ProbeMatch: a tool for aligning oligonucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1424–1425. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam TW, et al. Compressed indexing and local alignment of DNA. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:791–797. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, et al. ZOOM! Zillions of oligos mapped. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2431–2437. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippert RA. Space-efficient whole genome comparisons with Burrows-Wheeler transforms. J. Comput. Biol. 2005;12:407–415. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2005.12.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 2008a;18:1851–1858. doi: 10.1101/gr.078212.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, et al. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2008b;24:713–714. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhis N, et al. Slider–maximum use of probability information for alignment of short sequence reads and SNP detection. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:6–13. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz M. Cloudburst: highly sensitive read mapping with mapreduce. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1363–1369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AD, et al. Using quality scores and longer reads improves accuracy of Solexa read mapping. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]