Abstract

Lysyl oxidase (LOX) and LOX-like protein-1 (LOXL-1) are extracellular matrix-embedded amine oxidases that have critical roles in the cross-linking of collagen and elastin. LOX family proteins are abundantly expressed in the remodeled heart of animals and humans and are implicated in cardiac fibrosis; however, their role in cardiac hypertrophy is unknown. In this study, in vitro stimulation with hypertrophic agonists significantly increased LOXL-1 expression, LOX enzyme activity and [3H] leucine incorporation in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. A LOX inhibitor, beta-aminopropionitrile (BAPN), inhibited agonist-induced leucine incorporation in cardiomyocytes in vitro, suggesting the involvement of LOXL-1 in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Abdominal aortic constriction in rats produced left ventricular hypertrophy in parallel with LOXL-1 mRNA upregulation. And BAPN administration significantly inhibited angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. These results suggest a role of LOXL-1 in cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. We generated transgenic mice with cardiomyocyte-specific expression of LOXL-1. LOXL-1 transgenic mice pups were born normally and grew to adulthood without increased mortality; these mice exhibited a greater left ventricle to body weight ratio, larger myocyte diameter, and more brain natriuretic peptide expression than their wild-type littermates. Echocardiography revealed that the LOXL-1 transgenic mice also had greater wall thickness with preserved cardiac contraction. Our results indicate a possible fundamental role of LOXL-1 in cardiac hypertrophy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lysyl oxidase (LOX) family proteins are copper-dependent, extracellular matrix-embedded amine oxidases that have critical roles in the cross-linking of collagen and elastin fibrils, resulting in the deposition of insoluble collagen and elastic fibers.1, 2 Mammalian genomes have five isoforms encoding the prototypic LOX and LOX-like proteins 1 through 4 (LOXL-1, LOXL-2, LOXL-3 and LOXL-4).3, 4 These proteins have a conserved C-terminal region corresponding to the catalytic domain, which includes the lysine tyrosylquinone cofactor, the copper-binding site and the cytokine receptor-like domain.5 They exhibit different in vivo expression patterns and have different biological roles, including extracellular matrix stabilization, cell proliferation, cell growth and intracellular signal response.5

In 2006, we reported that LOXL-1 mRNA was upregulated in pressure overloaded hypertrophied hearts induced by abdominal aortic constriction (AAC).6 Since then, similar findings have been reported in animal models of diet-induced fibrotic hearts, cardiac remodeling of diet-induced metabolic syndrome and hypertrophied hearts of spontaneously hypertensive rats,7, 8, 9 as well as in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure.10, 11 These studies found upregulation of both mRNA and protein levels of LOX family in the remodeled hearts, and these expression levels were correlated with the degree of cardiac fibrosis, indicating that LOX and LOXLs have a role in cardiac remodeling by inducing fibrosis.12, 13 Interestingly, LOXL-1 was also reportedly upregulated in hypertrophied cardiomyocytes, suggesting a role for LOXL-1 in cardiac hypertrophy;1, 14 however, this issue has never been addressed. Accordingly, we generated cardiomyocyte-specific LOXL-1 transgenic mice (LOXL-1-TG) and investigated whether LOXL-1 overexpression would result in cardiac hypertrophy, especially cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.

Methods

Cardiomyocyte culture

Neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes were prepared using a Percoll gradient method as described previously.15, 16 Myocytes from 1–2-day-old rats were plated in serum-containing medium overnight. The cells were then cultured in serum-free medium for an additional 24 h before biochemical analysis.

LOX enzyme assay and incorporation of [3H] leucine

LOX amine oxidase assay was performed as previously described.17 Cells were homogenized in 300 μl of CelLytic (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) at −80 °C, then brought to a volume of 1 ml with LOX buffer (1.2 mol l−1 urea, 50 mmol l−1 sodium borate (pH 8.2)) and centrifuged at 12 000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and final concentrations of 1 μ ml−1 horseradish peroxidase, 10 μM Amplex red (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 10 mM 1,5-diaminopentane were added, and these solutions were incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. The fluorescence intensities were then recorded with excitation and emission wavelengths at 563 and 587 nm using Ascent Software version2.6 (Thermo Labsystems, Franklin, MA, USA).

Cardiomyocytes were stimulated with angiotensin II (AT-II; 10−6 μM) or endothelin-1 (10−7 μM) in the absence or presence of beta-aminopropionitrile (BAPN; 100 μM), a LOX inhibitor, for 24 h. Then, the incorporation of [3H] leucine in cells was measured as described by Thaik et al.18

AAC model

AAC was performed on male Wistar rats as described previously.6 At the indicated time after surgery, animals were killed and the hearts were removed. Left ventricles (LV) were weighed and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen for total RNA extraction.16 LOXL-1 mRNA expression was measured by real-time PCR. All experimental procedures were performed according to the guidelines established by the Kurume University Animal Care and Treatment Committee for experiments in animals.

In vivo AT-II infusion and BAPN treatment

Experiments were performed with 8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA). To induce cardiac hypertrophy, AT-II (1000 ng kg−1 min−1) was continuously infused subcutaneously for 14 days via an osmotic mini-pump (ALZET, Cupertino, CA, USA)19, 20. The control group received a saline infusion. AT-II- or saline-infused mice were further divided into two groups; mice fed either normal chow or chow containing 0.5% BAPN for 14 days (starting on the same day as the AT-II infusion). Accordingly, the experiments included four groups of mice; saline infusion plus normal chow (saline group), saline infusion plus BAPN-containing chow (saline+BAPN group), AT-II infusion plus normal chow (AT-II group) and AT-II infusion plus BAPN-containing chow (AT-II+BAPN group). At day 14 after the infusion, cardiac hypertrophy was examined using echocardiography as described below. Then mice were killed, the hearts were removed, LV were weighed and histological analysis was performed.

Generation of cardiac-specific LOXL-1 transgenic mice

We generated transgenic mice expressing LOXL-1 under the control of the cardiomyocyte-specific α-myosin heavy chain (αMHC) promoter.21, 22, 23 The pBSII-αMHC-LOXL-1 vector was constructed by subcloning the human LOXL-1 cDNA (accession no: NM_005576) into the pBSII-αMHC plasmid (generously provided by S Morimoto, Kyushu University). After digestion with SalI, the fragment carrying the αMHC promoter and human LOXL-1 cDNA was microinjected into (C57BL/6 × C3H) F1 (B6C3-F1) zygotes. Eggs surviving microinjection were transferred into the oviducts of recipient pseudopregnant females. Transgene expression in three mouse lines was confirmed by immunoblotting with an anti-LOXL-1 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) (Figure 4a). Three independent lines of transgenic mice were established, which were backcrossed with C57B6 mice for eight generations. For this study, we used transgenic mouse line A. As the anti-LOXL-1 antibody reacts with human LOXL-1, no expression of LOXL-1 was observed in wild-type (WT) mice in Figure 4a.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Total RNA from LV was prepared with an RNeasy Midi Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) and 1 μg of total RNA was converted into cDNA. Real-time PCR assays were performed to assess the gene expression of mouse LOXL-1 and mouse brain natriuretic peptide with the corresponding primer pairs (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Expression values for each gene were normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA (TaqMan ribosomal RNA control reagents; Applied Biosystems).24

Histology

To perform histological analyses, the hearts were fixed in 10% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. The samples were sectioned (5 μm thick) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Mallory–Azan or Sirius red. The cross-sectional area of myocytes and the area of fibrosis were quantified from the digital photomicrographs of the hematoxylin and eosin-, Mallory–Azan- and Sirius red-stained sections, respectively. All measurements were completed with the use of Image-J (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA, version 1.36).

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiographic studies were performed under light anesthesia with a Vevo770 ultrasound machine (VisualSonics, Inc., Toronto, Canada) equipped with a 30-MHz probe. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and subjected to echocardiography as previously described.22, 23, 24 Recording was performed as described previously.22, 23, 24

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means±s.e. Comparisons of mean values were performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Scheffe’s test. P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Hypertrophic agonists increased LOXL-1 expression and LOX enzyme activity in rat cardiomyocytes in vitro

We examined whether hypertrophic agonists would increase LOXL-1 expression in cultured rat cardiomyocytes. As shown in Figure 1a, LOXL-1 expression was significantly increased after stimulation with norepinephrine, AT-II, ET-1 or insulin-like growth factor-1. Next, we examined the effects of the hypertrophic agonists AT-II and ET-1 and found that both significantly upregulated the LOX enzyme activity of rat cardiomyocytes (Figure 1b). AT-II and ET-1 also significantly increased [3H] leucine incorporation into rat cardiomyocytes (Figure 1c). BAPN, a nonspecific inhibitor of LOX family proteins, inhibited hypertrophic AT-II- and ET-1-induced [3H] leucine incorporation (Figure 1c).

BAPN inhibited hypertrophic agonist-induced leucine incorporation in cardiomyocytes. (a) Real-time PCR for LOXL-1 after cardiomyocytes were stimulated with hypertrophic agonists for 24 h. Values are normalized to 18S rRNA and expressed as a fold change from control. *P<0.05 vs. control. (b) LOX enzyme assay after cardiomyocytes were stimulated with AT-II or ET-1 for the indicated times. *P<0.05 vs. time 0. (c) Measurement of [3H] leucine incorporation into cardiomyocytes, indicating effects of LOX enzyme inhibitor BAPN on AT-II or ET-1-induced hypertrophic response. ET-1, endothelin-1; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; NE, norepinephrine.

LOXL-1 expression upregulation was associated with cardiac hypertrophy after AAC

We examined the time course of cardiac remodeling and expression of LOXL-1 in the heart after AAC. For up to 28 days after AAC, the LV weight-to-body weight (BW) ratio was increased (Figure 2a) in parallel with upregulation of LOXL-1 mRNA (Figure 2b).

LOXL-1 expression in the heart after AAC in rats (a) LV/BW ratio in rats after AAC (n=6). (b) Real-time PCR analysis for LOXL-1 using total RNA from LV at the indicated time after AAC. Values are normalized to 18S rRNA and expressed as a fold change from control rats (n=6 for each group). *P<0.05 vs. control.

BAPN treatment inhibited AT-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vivo

We examined the effects of BAPN, an inhibitor of LOX, on cardiac hypertrophy induced by AT-II stimulation in vivo. AT-II infusion induced cardiac hypertrophy (Figures 3a and b). BAPN abolished the AT-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Sirius red staining showed that AT-II induced cardiac fibrosis significantly, which was abolished by the BAPN treatment (Figure 3c).

Inhibition of AT-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy by BAPN administration in vivo. (a) LV/BW ratio, (b) LV wall thickness estimated by echocardiography (c) and interstitial cardiac fibrosis analyzed by Sirius red staining in AT-II- or saline-infused mice that were fed BAPN-containing chow or standard chow-fed mice (n=6–8). *P<0.05 vs. saline-infused, standard chow-fed mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. IVST, interventricular septum thickness; PWT, posterior LV wall thickness.

Generation of cardiomyocyte-specific LOXL-1 transgenic mice

We generated transgenic mice expressing LOXL-1 under the control of the αMHC promoter. Pups of LOXL-1-TG mice were born normally and grew to adulthood without increased mortality. Blood pressure and heart rate were comparable between LOXL-1-TG and WT mice (data not shown). Until 8 weeks after birth, the magnitude of cardiac hypertrophy evaluated by LV/BW ratio (Figure 4b), cardiomyocyte diameter (Figure 4c) and brain natriuretic peptide mRNA level (Figure 4d) and the degree of fibrosis (Figure 4e) were comparable between WT and LOXL-1-TG mice. At 18 weeks of age, the magnitude of cardiac hypertrophy and the degree of fibrosis were significantly greater in LOXL-1-TG mice than those in WT mice.

Time course of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in LOXL-1 transgenic mice (LOXL-1-TG). (a) Immunoblotting with anti-LOXL-1 antibody showing LOXL-1 expression in the heart among three LOXL-1 transgenic lines (lanes A–C). (b) Time course the LV/BW ratio, (c) cross-sectional myocyte diameter (d) and myocardial brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) expression in LOXL-1-TG mice were significantly greater than those in WT mice (n=6–8). Values of BNP mRNA are normalized to 18S rRNA and expressed as a fold change from WT mice. *P<0.05 vs. WT mice. (e) Time course analysis of Mallory–Azan staining showing the interstitial cardiac fibrosis in LOXL-1-TG mice and WT mice. Pooled data of interstitial fibrosis are shown. *P<0.05 vs. WT mice.

Echocardiography demonstrated thicker LV walls in LOXL-1-TG mice than WT mice (Figure 5). LV diastolic or systolic dimensions and fractional shortening were comparable between WT and LOXL-1-TG mice (Figure 5).

Cardiac hypertrophy with preserved left ventriculer contraction in LOXL-1 transgenic mice (LOXL-1-TG). Representative M-mode ECGs obtained from WT and LOXL-1-TG mice. Pooled data for echocardiographic measurements in WT and LOXL-1-TG mice. *P<0.05 vs. WT mice. IVST, interventricular septum thickness; LVDd, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVDs, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; PWT, posterior LV wall thickness.

Discussion

The present study focused on the role of the copper-dependent, extracellular matrix-embedded amine oxidase LOXL-1 in cardiac hypertrophy. Our in vitro experiments showed that hypertrophic agonists increased LOXL-1 expression, LOX enzyme activity and [3H] leucine incorporation in rat cardiomyocytes. A LOX inhibitor, BAPN, inhibited the agonist-induced [3H] leucine incorporation in vitro and AT-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. The time course of LOXL-1 expression upregulation paralleled that of cardiac remodeling after AAC. Finally, cardiomyocyte-specific transgenic expression of LOXL-1 induced cardiac remodeling and myocyte hypertrophy. These results suggest that LOXL-1 may have a fundamental role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy.

In order to determine the involvement of LOXL-1 in cardiac hypertrophy, we examined LOXL-l mRNA and LOX enzyme activity in response to hypertrophic agonists in rat cardiomyocytes. Although the hypertrophic agonists upregulated these, they could be nonspecific responses unrelated cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Because leucine incorporation is a measure of myocyte hypertrophy, we examined whether a LOX enzyme inhibitor, BAPN, inhibited the agonist-induced leucine incorporation into cardiomyocytes. It was demonstrated with the use of active forms of recombinant LOX family proteins that BAPN inhibited LOX enzyme activity induced by not only LOX but also other LOX family proteins including LOXL-1.25 As shown in Figure 1c, BAPN inhibited the hypertrophic agonists-induced leucine incorporation, suggesting that the agonists-induced leucine incorporation was mediated by the increase in LOX enzyme activity. Taken together, the involvement of LOXL-1 in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy was suggested in vitro.

In order to further examine the involvement of LOXL-1 in cardiac hypertrophy, we examined LOXL-1 mRNA expression in the pressure-overloaded rat heart induced by AAC. As we reported previously,6 LOXL-1 mRNA was upregulated at 28 days after AAC (Figure 2b). Moreover, in the present study, the time course of LOXL-1 mRNA expression was similar to that of cardiac remodeling (Figure 2a). The high expression observed at day 1 may indicate a nonspecific response to surgical insult, or may suggest an important role of LOXL-1 in cardiac remodeling because the LOXL-1 upregulation preceded the development of cardiac remodeling. The time course of LOXL-1 upregulation paralleled that of cardiac remodeling after AAC, suggesting a role of LOXL-1 in cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. However, these are not conclusive because cardiac remodeling represents cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Moreover, the expression of LOXL-1 may be just an epiphenomenon of cardiac remodeling. Therefore, we examined the effect of a LOX enzyme inhibitor, BPAN, on the in vivo cardiac hypertrophy induced by AT-II (Figure 3). BPAN inhibited the AT-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy, suggesting that LOX family proteins are involved in the development of cardiac hypertrophy.

In order to examine the fundamental role of LOXL-1, we generated cardiomyocyte-specific LOXL-1 transgenic mice. As shown in Figure 4, the transgenic mice exhibited cardiac remodeling associated with cardiac brain natriuretic peptide upregulation. Moreover, the myocyte diameter was much greater in the LOXL-1-TG mice than that in WT mice, indicating that LOXL-1 has a fundamental role in cardiac hypertrophy. Although the degree of cardiac fibrosis was greater in the LOXL-1-TG mice than in the WT mice, this was probably a secondary phenomenon due to cardiac hypertrophy, because LOXL-1 was specifically induced only in cardiomyocytes and because the time course of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis were similar. Real-time PCR analysis revealed that expression of collagen I and collagen III at both 4 weeks and 18 weeks of age were comparable between WT and LOXL-1-TG mice (data not shown). It is possible that LOXL-1 may post-transcriptionally regulate the cross-linking of collagen and elastin. In future studies, it will be interesting to examine changes in extracellular matrix proteins in LOXL-1-TG mice.

Possible mechanisms by which LOXL-1 causes cardiomyocyte hypertrophy

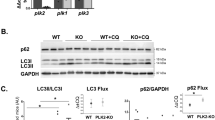

It has been suggested that the functions of LOX family proteins extend beyond their roles in stabilizing the extracellular matrix,1, 26, 27, 28, 29 as they can oxidize lysine within a variety of cationic proteins.5 Indeed, recent findings revealed that LOX family proteins markedly influence cell behavior, including chemotactic responses, cell growth and intracellular signaling and transcription.1, 26, 27, 28, 29 Recently, Eliades et al. reported that LOX inhibition with BAPN reduces downstream signaling of platelet-derived growth factor receptor, including activation of Akt and ERK1/2 pathways, and diminishes the proliferative effect of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor on the megakaryocyte lineage,30 suggesting that LOX proteins have a functional role in growth factor receptor signaling and cell growth. In the present study, we examined the activation of AKT and ERK1/2 by western blot. The phosphorylation of both AKT and ERK1/2 were comparable between WT and LOXL-1-TG mice (Supplementary Figure). The mechanisms by which LOXL-1 caused cardiomyocyte hypertrophy remain to be elucidated.

Limitations

As LOXL-1 was specifically overexpressed only in cardiomyocytes, the present study did not reveal the mechanisms of cardiac fibrosis in our transgenic mice.

Clinical implications

In our aging society, the prevalence of heart failure with preserved systolic function (diastolic failure) has been rapidly increasing. The pathophysiological mechanisms of diastolic dysfunction include cardiac fibrosis and cardiac hypertrophy. In the present study, we have shown that LOXL-1 is fundamentally involved in cardiac hypertrophy. We generated transgenic mice with cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression of LOXL-1, and these mice exhibited cardiac remodeling characterized by hypertrophy and fibrosis. Although we did not examine diastolic function in our transgenic mice, it is very plausible that they exhibit diastolic dysfunction. Accordingly, our results suggest that production of drugs that interfere with LOXL-1 function will be useful for preventing cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy in patients with diastolic dysfunction.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the extracellular matrix-embedded amine oxidase LOXL-1 may have a fundamental role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy.

Accession codes

References

López B, González A, Hermida N, Valencia F, de Teresa E, Díez J . Role of lysyl oxidase in myocardial fibrosis: from basic science to clinical aspects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2010; 299: H1–H9.

Rodríguez C, Martínez-González J, Raposo B, Alcudia JF, Guadall A, Badimon L . Regulation of lysyl oxidase in vascular cells: lysyl oxidase as a new player in cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc Res 2008; 79: 7–13.

Molnar J, Fong KS, He QP, Hayashi K, Kim Y, Fong SF, Fogelgren B, Szauter KM, Mink M, Csiszar K . Structural and functional diversity of lysyl oxidase and the LOX-like proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003; 1647: 220–224.

Kagan HM, Li W . Lysyl oxidase: properties, specificity, and biological roles inside and outside of the cell. J Cell Biochem 2003; 88: 660–672.

Lucero HA, Kagan HM . Lysyl oxidase: an oxidative enzyme and effector of cell function. Cell Mol Life Sci 2006; 63: 2304–2316.

Miyazaki H, Oka N, Koga A, Ohmura H, Ueda T, Imaizumi T . Comparison of gene expression profiling in pressure and volume overload-induced myocardial hypertrophies in rats. Hypertens Res 2006; 29: 1029–1045.

Zibadi S, Vazquez R, Larson DF, Watson RR . T lymphocyte regulation of lysyl oxidase in diet-induced cardiac fibrosis. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2010; 10: 190–198.

Zibadi S, Vazquez R, Moore D, Larson DF, Watson RR . Myocardial lysyl oxidase regulation of cardiac remodeling in a murine model of diet-induced metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009; 297: H976–H982.

Hermida N, López B, González A, Dotor J, Lasarte JJ, Sarobe P, Borrás-Cuesta F, Díez J . A synthetic peptide from transforming growth factor-beta1 type III receptor prevents myocardial fibrosis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Cardiovasc Res 2009; 81: 601–609.

Sivakumar P, Gupta S, Sarkar S, Sen S . Upregulation of lysyl oxidase and MMPs during cardiac remodeling in human dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol Cell Biochem 2008; 307: 159–167.

López B, Querejeta R, González A, Beaumont J, Larman M, Díez J . Impact of treatment on myocardial lysyl oxidase expression and collagen cross-linking in patients with heart failure. Hypertension 2009; 53: 236–242.

Yu Q, Vazquez R, Zabadi S, Watson RR, Larson DF . T-lymphocytes mediate left ventricular fibrillar collagen cross-linking and diastolic dysfunction in mice. Matrix Biol 2010; 29: 511–518.

Adam O, Theobald K, Lavall D, Grube M, Kroemer HK, Ameling S, Schäfers HJ, Böhm M, Laufs U . Increased lysyl oxidase expression and collagen cross-linking during atrial fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2011; 50: 678–685.

Hayashi K, Fong KS, Mercier F, Boyd CD, Csiszar K, Hayashi M . Comparative immunocytochemical localization of lysyl oxidase (LOX) and the lysyl oxidase-like (LOXL) proteins: changes in the expression of LOXL during development and growth of mouse tissues. J Mol Histol 2004; 35: 845–855.

Koga A, Oka N, Kikuchi T, Miyazaki H, Kato S, Imaizumi T . Adenovirus-mediated overexpression of caveolin-3 inhibits rat cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Hypertension 2003; 42: 213–219.

Yasukawa H, Hoshijima M, Gu Y, Nakamura T, Pradervand S, Hanada T, Hanakawa Y, Yoshimura A, Ross J, Chien KR . Suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 is a biomechanical stress-inducible gene that suppresses gp130-mediated cardiac myocyte hypertrophy and survival pathways. J Clin Invest 2001; 108: 1459–1467.

Palamakumbura AH, Trackman PC . A fluorometric assay for detection of lysyl oxidase enzyme activity in biological samples. Anal Biochem 2002; 300: 245–251.

Thaik CM, Calderone A, Takahashi N, Colucci WS . Interleukin-1 beta modulates the growth and phenotype of neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest 1995; 96: 1093–1099.

Yamazaki T, Yamashita N, Izumi Y, Nakamura Y, Shiota M, Hanatani A, Shimada K, Muro T, Iwao H, Yoshiyama M . The antifibrotic agent pirfenidone inhibits angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Hypertens Res 2012; 35: 34–40.

Kawano S, Kubota T, Monden Y, Kawamura N, Tsutsui H, Takeshita A, Sunagawa K . Blockade of NF-kappaB ameliorates myocardial hypertrophy in response to chronic infusion of angiotensin II. Cardiovasc Res 2005; 67: 689–698.

Subramaniam A, Jones WK, Gulick J, Wert S, Neumann J, Robbins J . Tissue-specific regulation of the alpha-myosin heavy chain gene promoter in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem 1991; 266: 24613–2420.

Yasukawa H, Yajima T, Duplain H, Iwatate M, Kido M, Hoshijima M, Weitzman MD, Nakamura T, Woodard S, Xiong D, Yoshimura A, Chien KR, Knowlton KU . The suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS1) is a novel therapeutic target for enterovirus-induced cardiac injury. J Clin Invest 2003; 111: 469–478.

Yajima T, Yasukawa H, Jeon ES, Xiong D, Dorner A, Iwatate M, Nara M, Zhou H, Summers-Torres D, Hoshijima M, Chien KR, Yoshimura A, Knowlton KU . Innate defense mechanism against virus infection within the cardiac myocyte requiring gp130-STAT3 signaling. Circulation 2006; 114: 2364–2373.

Oba T, Yasukawa H, Hoshijima M, Sasaki KI, Futamata N, Fukui D, Mawatari K, Nagata T, Kyogoku S, Ohshima H, Minami T, Nakamura K, Kang D, Yajima T, Knowlton KU, Imaizumi T . Cardiac-specific deletion of SOCS-3 prevents development of left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 59: 838–852.

Jung ST, Kim MS, Seo JY, Kim HC, Kim Y . Purification of enzymatically active human lysyl oxidase and lysyl oxidase-like protein from Escherichia coli inclusion bodies. Protein Expr Purif 2003; 31: 240–246.

Liu X, Zhao Y, Gao J, Pawlyk B, Starcher B, Spencer JA, Yanagisawa H, Zuo J, Li T . Elastic fiber homeostasis requires lysyl oxidase-like 1 protein. Nat Genet 2004; 36: 178–182.

Bignon M, Pichol-Thievend C, Hardouin J, Malbouyres M, Bréchot N, Nasciutti L, Barret A, Teillon J, Guillon E, Etienne E, Caron M, Joubert-Caron R, Monnot C, Ruggiero F, Muller L, Germain S . Lysyl oxidase-like protein-2 regulates sprouting angiogenesis and type IV collagen assembly in the endothelial basement membrane. Blood 2011; 118: 3979–3989.

Voloshenyuk TG, Landesman ES, Khoutorova E, Hart AD, Gardner JD . Induction of cardiac fibroblast lysyl oxidase by TGF-β1 requires PI3K/Akt, Smad3, and MAPK signaling. Cytokine 2011; 55: 90–97.

Onoda M, Yoshimura K, Aoki H, Ikeda Y, Morikage N, Furutani A, Matsuzaki M, Hamano K . Lysyl oxidase resolves inflammation by reducing monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis 2010; 208: 366–369.

Eliades A, Papadantonakis N, Bhupatiraju A, Burridge KA, Johnston-Cox HA, Migliaccio AR, Crispino JD, Lucero HA, Trackman PC, Ravid K . Control of megakaryocyte expansion and bone marrow fibrosis by lysyl oxidase. J Biol Chem 2011; 286: 27630–27638.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kimiko Kimura, Miyuki Nishigata, Makiko Kiyohiro and Miho Kogure for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported in part by a grant for the Science Frontier Research Promotion Centers (Cardiovascular Research Institute); by grants-in-aid for Scientific Research (TM, HY, YS) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan; by a Research Grant for Cardiovascular Diseases from Kimura Memorial Heart Foundation (HY); by a Research Grant from Takeda Memorial Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Hypertension Research website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ohmura, H., Yasukawa, H., Minami, T. et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific transgenic expression of lysyl oxidase-like protein-1 induces cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Hypertens Res 35, 1063–1068 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.92

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.92

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Fibroblasts orchestrate cellular crosstalk in the heart through the ECM

Nature Cardiovascular Research (2022)

-

Heart regeneration in the salamander relies on macrophage-mediated control of fibroblast activation and the extracellular landscape

npj Regenerative Medicine (2017)

-

Matrix regulation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the role of enzymes

Fibrogenesis & Tissue Repair (2013)