Abstract

The 2023 Mexican Healthy and Sustainable Dietary Guidelines (HSDG 2023) were developed to include all dimensions of sustainability. Here we compare the environmental impact and cost of diets based on the HSDG 2023, current diets and the Mexican-adapted EAT healthy reference diet. Diets following HSDG 2023 are 21% less expensive, require 30% less land to be produced and have 34% less carbon emissions than current diets—particularly in Mexico City and other urban areas with higher prevalence of Westernized diets. This is driven by reduced animal-source food, especially red meat, and ultra-processed foods. In south–rural areas, the water footprint and cost of diets following HSDG 2023 were higher than those of current diets owing to increased intake of nuts, fruits and vegetables not offset by lower meat consumption (which is already close to recommendations). Diet environmental impact and cost could be further reduced with the Mexican-adapted EAT healthy reference diet compared with the HSDG 2023.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Dietary information from ENSANUT 2016 is publicly available at https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2016/descargas.php, food prices are available at https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/preciospromedio/ and data on environmental indicators for food production are available at https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.855793/full#supplementary-material. The dataset analysed during our study is available via the open Figshare repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25749708 (ref. 48). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code (do-files) in STATA version 15 used for the data analysis is available via the open Figshare repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25749708 (ref. 48).

References

Steffen, W. et al. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347, 1259855 (2015).

Atwoli, L. et al. Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health. Lancet Reg. Health 9, 939–941 (2021).

Rockström, J., Stordalen, G. A. & Horton, R. Acting in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission. Lancet 387, 2364–2365 (2016).

Arias, P. A. et al. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 33−144 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Crippa, M. et al. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat. Food 2, 198–209 (2021).

Swinburn, B. A. et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet 393, 791–846 (2019).

Poore, J. & Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 360, 987–992 (2018).

Anastasiou, K., Baker, P., Hadjikakou, M., Hendrie, G. A. & Lawrence, M. A conceptual framework for understanding the environmental impacts of ultra-processed foods and implications for sustainable food systems. J. Clean. Prod. 368, 133155 (2022).

Willett, W. et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 393, 447–492 (2019).

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) & World Health Organization (WHO). Sustainable Healthy Diets (2019); https://doi.org/10.4060/CA6640EN

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP & WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets (2020); https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9692en

Rao, M., Afshin, A., Singh, G. & Mozaffarian, D. Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 3, e004277 (2013).

Darmon, N. & Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr. Rev. 73, 643–660 (2015).

Hirvonen, K., Bai, Y., Headey, D. & Masters, W. A. Affordability of the EAT–Lancet reference diet: a global analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 8, e59–e66 (2020).

Batis, C. et al. Adoption of healthy and sustainable diets in Mexico does not imply higher expenditure on food. Nat. Food 2, 792–801 (2021).

Curi-Quinto, K. et al. Sustainability of diets in Mexico: diet quality, environmental footprint, diet cost, and sociodemographic factors. Front. Nutr. 9, 855793 (2022).

Barquera, S. & Rivera, J. A. Obesity in Mexico: rapid epidemiological transition and food industry interference in health policies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 8, 746–747 (2020).

Crippa, M. et al. The EDGAR-FOOD dataset. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13476666 (2021)

SEMARNAT. Disponibilidad del Agua. Informe del Medio Ambiente en México. (2018); https://apps1.semarnat.gob.mx:8443/dgeia/informe18/tema/cap6.html

Guibrunet, L., Ortega-Avila, A. G., Arnés, E. & Ardila, F. M. Socioeconomic, demographic and geographic determinants of food consumption in Mexico. PLoS ONE 18, e0288235 (2023).

SSA, INSP & UNICEF. Guias Alimentarias Saludables y Sostenibles Para la Población Mexicana 2023. Secretaría de Salud (2023); https://www.gob.mx/promosalud/articulos/que-son-las-guias-alimentarias

Castellanos-Gutiérrez, A., Sánchez-Pimienta, T. G., Batis, C., Willett, W. & Rivera, J. A. Toward a healthy and sustainable diet in Mexico: where are we and how can we move forward? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 113, 1177–1184 (2021).

Aburto, T. C., Pedraza, L. S., Sánchez-Pimienta, T. G., Batis, C. & Rivera, J. A. Discretionary foods have a high contribution and fruit, vegetables, and legumes have a low contribution to the total energy intake of the Mexican population. J. Nutr. 146, 1881S–1887S (2016).

Tilman, D. & Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 515, 518–522 (2014).

James-Martin, G. et al. Environmental sustainability in national food-based dietary guidelines: a global review. Lancet Planet. Health 6, e977–e986 (2022).

Kovacs, B., Miller, L., Heller, M. C. & Rose, D. The carbon footprint of dietary guidelines around the world: a seven country modeling study. Nutr. J. 20, 15 (2021).

van de Kamp, M. E. et al. Healthy diets with reduced environmental impact?—The greenhouse gas emissions of various diets adhering to the Dutch food based dietary guidelines. Food Res. Int. 104, 14–24 (2018).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Resources. Global Livestock Environmental Assessment Model (GLEAM) https://www.fao.org/gleam/en/ (2015).

Ibarrola-Rivas, M.-J., Unar-Munguia, M., Kastner, T. & Nonhebel, S. Does Mexico have the agricultural land resources to feed its population with a healthy and sustainable diet?. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 34, 371–384 (2022).

Tuninetti, M., Ridolfi, L. & Laio, F. Compliance with EAT–Lancet dietary guidelines would reduce global water footprint but increase it for 40% of the world population. Nat. Food 3, 143–151 (2022).

Sultana, F. Whose growth in whose planetary boundaries? Decolonising planetary justice in the Anthropocene. Geo Geogr. Environ. 10, e00128 (2023).

Ponce-Alcala, R. E., Luna, J. L. R.-G., Shamah-Levy, T. & Melgar-Quiñonez, H. The association between household food insecurity and obesity in Mexico: a cross-sectional study of ENSANUT MC 2016. Public Health Nutr. 24, 5826–5836 (2021).

Vega-Macedo, M., Shamah-Levy, T., Peinador-Roldán, R., Méndez-Gómez Humarán, I. & Melgar-Quiñónez, H. Food insecurity and variety of food in Mexican households with children under five years [in Spanish]. Salud Publica Mex. 56, s21–s30 (2014).

Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística (INEGI) Precios Promedio. INEGI https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/preciospromedio/ (2016).

Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social Evolución de las lineas de pobreza por ingresos. https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/MP/Paginas/Lineas-de-Pobreza-por-Ingresos.aspx (2024).

Clune, S., Crossin, E. & Verghese, K. Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories. J. Clean. Prod. 140, 766–783 (2017).

Heller, M. C., Willits-Smith, A., Mahon, T., Keoleian, G. A. & Rose, D. Individual US diets show wide variation in water scarcity footprints. Nat. Food 2, 255–263 (2021).

Huang, K. et al. Comparison of the 24 h dietary recall of two consecutive days, two non-consecutive days, three consecutive days, and three non-consecutive days for estimating dietary intake of Chinese adult. Nutrients 14, 1960 (2022).

Rose, D., Heller, M. C., Willits-Smith, A. M. & Meyer, R. J. Carbon footprint of self-selected US diets: nutritional, demographic, and behavioral correlates. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 109, 535–543 (2019).

Conrad, Z., Drewnowski, A., Belury, M. A. & Love, D. C. Greenhouse gas emissions, cost, and diet quality of specific diet patterns in the United States. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 117, 1186–1194 (2023).

Romero-Martínez, M. et al. Diseño metodológico de la encuesta nacional de salud y nutrición de medio camino 2016. Salud Publica Mex. 59, 299–305 (2017).

Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición Medio Camino (ENSANUT MC 2016), Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2016/index.php (2016).

Turner, C. et al. Concepts and critical perspectives for food environment research: a global framework with implications for action in low- and middle-income countries. Glob. Food Secur. 18, 93–101 (2018).

Damschroder, L. J., Reardon, C. M., Widerquist, M. A. O. & Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 17, 75 (2022).

Ramírez-Silva, I. et al. Prevalence of inadequate intake of vitamins and minerals in the Mexican population correcting by nutrient retention factors, Ensanut 2016. Salud Publica Mex. 62, 521–531 (2020).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 1577–1600 (2011).

Banco Mundial Tasa de cambio oficial (UMN por US$, promedio para un período) | Data. World Bank http://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/PA.NUS.FCRF?end=2015&locations=CO&start=1960&view=chart (2015).

Unar-Munguía M. et al. Mexican national dietary guidelines promote less costly and environmentally sustainable diets. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25749708 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Committee of Experts, the Committee of Multisectoral Institutions from the Government, the Academia, the Civil Society Organizations and the Ministry of Health for their contributions to the development of the 2023 Mexican HSDG. We thank the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) Mexico for primarily funding this work (CI:1725 granted to A.B.A.) and the Mexican National Council of Humanity, Science and Technology (CONAHCyT) for partly funding this work through the Frontier in Science Call Pp F003 5/VIII-E/2022, project number 319721 granted to M.U.-M. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.U.-M., S.R.-R., A.C.F.G., J.A.R. and A.B.A. conceived the project. A.B.A. was the principal investigator of the development of the 2023 Mexican HSDG and was responsible for the overall project. M.U.-M. was responsible for developing the research plan related to environmental and cost analysis. M.U.-M., M.A.C.-A. and S.R.R. analysed the data, and M.A.C.-A. and M.U.-M. wrote the first draft. S.R.-R., A.C.F.G., J.A.R. and A.B.A. added important intellectual content. M.U.-M. and A.B.A. are primarily responsible for the final content. All authors read and approved the final paper as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Food thanks Malcolm Riley, Donald Rose and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

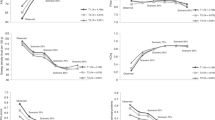

Extended Data Fig. 1 Figure S1. Average carbon and blue water footprint, and land use per kg of food group.

Estimations based on data from Curi-Quinto et al.16 SSB: Sugar-sweetened beverages, kgCO2eq: kilograms of dioxide carbon equivalents, m2: squared meters of land.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Figure S2. The carbon footprint by food groups for HSDG 2023, EAT-HRD-Mex and current adults diet.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Figure S3. The water footprint by food groups for HSDG 2023, EAT-HRD-Mex and current adults diet.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Figure S4. Land use by food group for HSDG 2023, EAT-HRD-Mex and current adult diet.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–4.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Unar-Munguía, M., Cervantes-Armenta, M.A., Rodríguez-Ramírez, S. et al. Mexican national dietary guidelines promote less costly and environmentally sustainable diets. Nat Food 5, 703–713 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01027-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01027-5