What is an EPC? Energy Performance Certificates Explained by an Expert

What is an EPC? Our sustainability expert Tim Pullen covers the basics, and offers advice on useful they are to home buyers and self builders

You might find yourself asking 'what is an EPC?' for a number of reasons, as it's required whether you're building, buying, selling or renting a house. An Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) outlines a property's energy use and potential energy costs, as well as how improvements can be made.

In this guide to EPCs, we take an deeper look at the roles Energy Performance Certificates play in the process of selling, buying and building a home, alongside how useful they are as indicators of your home's energy efficiency.

What is an EPC?

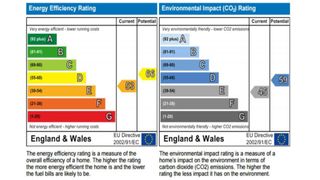

An Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) is a document that sets out the assessed energy efficiency and potential CO2 emissions for a property. The property is rated on a scale from A to G with A being excellent and G a disaster. Very, very few houses achieve an A-rating and most tend to be D or above. Those languishing in the E, F or G brackets need to be encouraged to take immediate action.

The document runs to 4 pages and also sets out the probable running cost for the house, suggests improvements that could be made to improve energy efficiency, the possible capital cost of those improvements and the benefit they could have on running costs and CO2 emissions.

What is the Purpose of an EPC?

At the basic level, it is a legal requirement that any property being sold or rented has an EPC that is less that 2 years old. As there is no legal requirement to improve the rating, the reason is likely to be to raise awareness of energy efficiency in properties, to put it on the agenda, as it were, to encourage us to think about it.

Perhaps it is hoped that it will influence house buyers in deciding which house to buy. And, therefore, in turn to encourage home owners to improve the thermal efficiency of their home, to get a better rating and to increase it saleability.

Theoretically that could happen, and it would be a good thing if it did, but there can’t be many people that, along with number of bedrooms, state of repair, local schools, size of garden, location, add an EPC rating of C or above to their home-buying criteria.

An EPC is also necessary for a Domestic Renewable Heat Incentive application (which closes in March 2022). Although an EPC is notionally valid for 10 years, all the actual uses — selling or renting property or RHI application — require an EPC that is less than 2 years old.

How is an EPC Calculated?

EPCs use what is essentially the same software as for SAP calculations, although there are two sets for EPCs, SAP and RdSAP.

SAP or Standard Assessment Procedure, is the method used for new build properties to assess their compliance with Building Regulations Part L. An RdSAP is a Reduced Data SAP calculation specifically for EPCs in existing properties where a full data set cannot be obtained.

Unlike EPC calculations, a SAP assessment results in a pass or fail and its accuracy is generally not questioned. For a new build the SAP calculation is likely to lead directly to an EPC that itself will be equally as accurate. However, personal experience has shown that there is a reasonable doubt over the accuracy of EPCs carried out for existing properties.

Almost universally the heat loss figure has varied from a heat loss calculation completed on a heating industry standard calculator. The difference has varied from a bit off to wildly inaccurate. It has also been shown that calculations carried out on the same property, at the same time, by different assessors can result in different outcomes. The reason for this is the way the data is gathered.

A SAP calculation is based on drawings and specification for that new build property. In that case the data — U-values, dimensions, materials, air tightness, etc — is defined and accurate, resulting in an accurate assessment. In the case of EPCs, data is gathered by “non-invasive survey”. In other words, a bit of a look around and a chat with the owners. Obviously that method is likely to result in inaccurate and/or incomplete data. And we can’t really blame the assessor for this, when all they can do is look at the element (wall, floor, window, etc) and ask the owner how much insulation it has and what type.

How Much Does an EPC Cost?

EPC assessments cost between £50 and £100. Prices vary, so it pays to shop around for the best deal.

(MORE: Need an EPC? Find a expert assessor near you)

How Useful is an EPC?

To a large extent the question is irrelevant as in any active situation — buying, selling, renting — we have to have one. Beyond that there is some discussion over their efficacy. A survey carried out by Survey and Test Ltd suggested that houses with an EPC rating of C or better could get a 2.8% higher sale price than a similar property with D or poorer rating.

Conversely, another survey carried out by Show House indicated that 25% of EPCs recorded the dimensions of the house with more than 10% inaccuracy, when floor area and volume of the house are critical to the calculation and have a direct impact on energy consumption.

Then there are the suggested improvements. These are generally “suggested” by the software in that if the assessor ticks the box for “no cavity wall insulation” the software will suggest installing that insulation and do all the calculations regarding probable cost and benefits. Which is exactly what happened to the owner of a 19th century house, with 500mm thick solid stone walls. The result was that the whole document was dismissed as being a farce.

We can conclude therefore, that if the reader is prepared to believe it, the EPC will have value. But that the methodology currently used to produce them does not instil any confidence in their accuracy or efficacy.

Get the Homebuilding & Renovating Newsletter

Bring your dream home to life with expert advice, how to guides and design inspiration. Sign up for our newsletter and get two free tickets to a Homebuilding & Renovating Show near you.

Tim is an expert in sustainable building methods and energy efficiency in residential homes and writes on the subject for magazines and national newspapers. He is the author of The Sustainable Building Bible, Simply Sustainable Homes and Anaerobic Digestion - Making Biogas - Making Energy: The Earthscan Expert Guide.

His interest in renewable energy and sustainability was first inspired by visits to the Royal Festival Hall heat pump and the Edmonton heat-from-waste projects. In 1979

this initial burst of enthusiasm lead to him trying (and failing) to build a biogas digester to convert pig manure into fuel, at a Kent oast-house, his first conversion project.

Moving in 2002 to a small-holding in South Wales, providing as it did access to a wider range of natural resources, fanned his enthusiasm for sustainability. He went on to install renewable technology at the property, including biomass boiler and wind turbine.

He formally ran energy efficiency consultancy WeatherWorks and was a speaker and expert at the Homebuilding & Renovating Shows across the country.