Beyond The Kiosk: Designing Digital Experiences for the Urban Streetscape

Cities are containers for all kinds of human experience, and the street level presents the purest canvas to witness the relationships, interactivity, and day to day life of the urban environment. At the civic scale, innovative technology solutions can address major infrastructure challenges ranging from climate resilience to mobility and access to public resources, but the opportunities for technology-enabled experiences at the street and human level offer exciting potential for participation in the urban environment that goes beyond digital kiosks and advertising platforms.

We sat down with Oliver Schaper, Cities & Urban Design Practice Area Leader for the Northeast region, and Emilie Baltz, Creative Director and Global Practice Area Leader Digital Experience Design to discuss how else technology can play a role in shaping our experiences of the city.

How do you consider designing for human experience on the street level?

Emilie Baltz: I'm interested in exploring how cities can inspire new ways of thinking and being. How might we design our environments to inspire new kinds of human relationships? I see the street as a flexible environment, a space full of intersections (literally and metaphorically), that we can leverage to create connections between people who may never have been able to connect.

This reminds me of the AT&T Discovery District, which uses design and technology at the street level to create intersectionality through multisensory play. The main thoroughfare in this zone is activated by an interactive dome: a public intervention that responds to guest movement through color and sound. It is accessible to all, inviting a sense of play and wonder within this urban thoroughfare, causing us to stop and experience emotions we might not otherwise have access to in a streetscape. and transformed the district's perception through the introduction of play, increasing foot traffic in the area from 25,000 people per month in 2019 to over 400,000 people per month in 2024. As an experience it drives memorability, fosters human interaction, and delights people – all delivering a unique kind of placemaking and destination creation for Dallas.

Oliver Schaper: When you design public spaces, the public realm, and cities in a context where you focus on experience not just as entertainment and interest-oriented, but in a way that covers all cross sections of the population, the public becomes your client. This includes those that struggle to have basic needs met, or that are left behind, or that don't participate in the way we'd like to describe what a city experience could or ought to be, down to the fact that we assume that if technology plays a role, everybody has access to these interfaces that are needed. You realize the disconnect between what's being offered and who can take advantage of that in what form.

Emilie Baltz: What makes a sidewalk interesting for you, the street level rather than the macro?

Oliver Schaper: As public space it's ideally the ultimate neutral ground where city life can occur. Within the confines of a social (and regulatory) contract, nothing is censored, and nothing is excluded on the sidewalk. It's the ultimate space in which community can occur in the most natural, unstaged, unrehearsed and uncontrolled way.

How can technology play a role in creating new modes of interacting with public space?

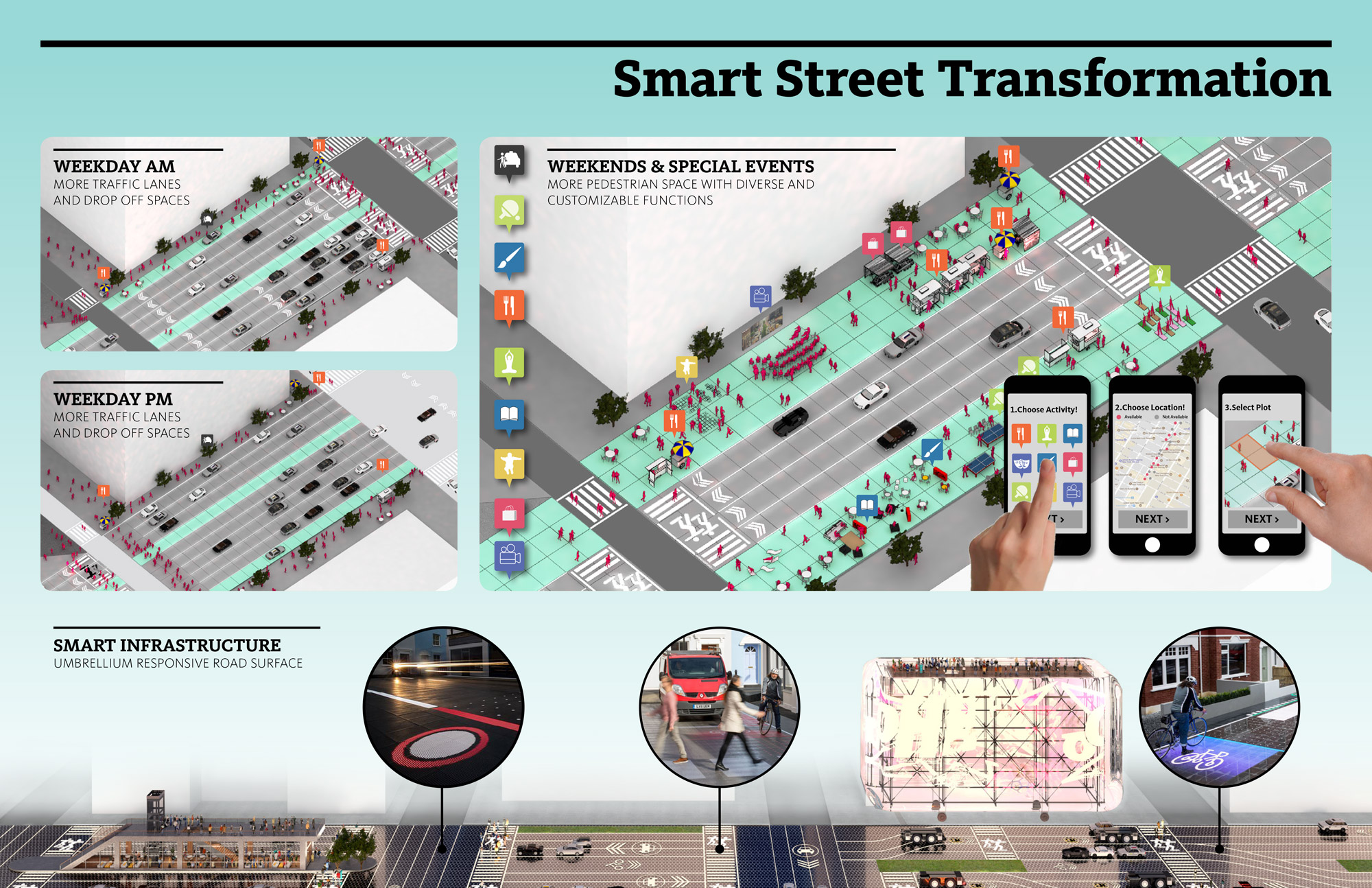

Oliver Schaper: Three or four years ago, we participated in a competition for Park Avenue to propose something more future oriented for the streetscape. We interpreted it as a way of saying, can you dynamically change the road? For example, after hours and weekends when Park Avenue’s commercial life is dead and traffic is not there, can you double the amount of sidewalk and then allow kind of programmable spaces for block parties that you can order on your iPhone? Can you have a technology-supported programmable surface that invites people to use public space differently and not get stuck designing for peak volume of traffic, for example, or peak volume of pedestrians, but be more flexible? In the proposed form this was a speculative project, but it points to the need for technology innovation and integration within the experiential dimensions of public realm

Emilie Baltz: Technology facilitates flexibility. In the scenario you describe on Park Avenue, I also think about technology as the backdrop for the theater of life. In this context I see it as enabling new scenographies that set the stage for all sorts of different kinds of experiences. We also know the more use a space can provide for its community the healthier, happier and interconnected its people become. This kind of flow and dynamism is the promise of urban living.

Oliver Schaper: It's also a nod to the fact that 35% of many cities are streets for cars. That's a tremendous amount of public potential. Space is always at a premium and one could say that there's a balance that can be struck between those competing interests for limited space — maybe technology helps with that.

Emilie Baltz: Many people, agnostic of being in urban space or any part of the built environment, still come to technology through the lens of a two-dimensional, screen-based experience. We see that in the consequences of street kiosks being the totems for urban technological infrastructure.

Experience in cities is also ambulatory. It's ephemeral. Instead of us still being pinned to the sense that technology can only be expressed through two dimensional flat surfaces on buildings — in Times Square, for example — what if it could start to promote new connections between people and new modes of engagement in the negative space in between buildings, in between people?

What shapes a positive experience of a city?

Oliver Schaper: Vibrancy and urban activity are magnets for a positive experience. When nobody's present, you might have a good experience, but everything is built around social, experiential settings. From the hardware of cities, we have learned over time that there are certain city models that are more conducive to producing this in others.

One of the poster childs for this city model, apart from all the European cities, is Portland, Oregon. The 200x200 foot block creates enough critical mass with functional entrances to public space to feed the sidewalk. And at the same time, there's a relationship between you walking 200 feet and having a choice of three directions and to go in. On the opposite spectrum, in planned cities like Brasilia, for example, you walk three quarters of a mile without a change of direction because you have these long blocks without functional entrances, and you perceive it as dead. I wonder if this idea of vibrancy can be enhanced through technology, through digital means.

The boundary of the public realm is a layer between public and private. You can design that layer rather than understand it as the leftover space between buildings or a sidewalk. You can give it a spatial structure intentionally set in place, versus an afterthought. There's an interesting opportunity for creating a tapestry that expresses what we're already living, which is that half of our way of moving, orienting. and getting information is physical, and the other half we retrieve from our smartphones.

Emilie Baltz: Perhaps our job within the urban experience is to start breaking boundaries down into borders, so there's more permeability. In the case of Brasilia, there is an opportunity for transformation; without having to necessarily change the entire streetscape, we might imagine experiences that offer new opportunities for permeating the city: being prompted to turn down a street and discover something you don't understand or know, or perhaps changing the character of a place through sound. This experience of discovery is one of the great joys of city life.

Technology-enabled experiences like social media or mobile gaming enable people to give character to streetscapes that, as you suggest, lack vibrancy, or add dimensionality and connectedness to the city. How might we think about cities as games?

Oliver Schaper: Cities could become a game in the idea of authorship, of planning ideas, urban storytelling, and community engagement that help to identify what the challengers are in a city or in a neighborhood through playful interaction which is more accessible than the technical discipline of planning.

We are moving away from this idea of “the few that know” and put up a “master” plan that remains valid for 30 years, to a more dynamic, context-driven scenario planning philosophy that focuses on the implementation of a single phase during one economic cycle, after its been tested to allow a number of different potential futures from occurring afterwards.

The city is an ever-changing image. I think that has a direct impact on how you experience cities today and tomorrow, even from the perspective of the layperson influencing the planning process and revealing their different perspective of what the city is, what it can do, and what you can do with it.

Emilie Baltz: Another piece of this that’s interesting to me is how these layers of technology can also function as lenses that unlock new readings of a space. As we think about diversity, inclusion, and representation, we have a responsibility to create access in our public realm for different learning styles and cultural narratives.

This might be delivered in a gameplay situation, an augmented reality exhibition, or a layer of audio that accompanies you — something that starts to educate and engage us in the different narratives held within a place. Be that in terms of revealing pre-colonial landscapes, supporting neurodiversity, or even identifying future emergence, the narrative layer changes our perception of place, but it’s the engagement with the story that changes our behavior. Being able to deliver narratives in multimodal experience that embrace all the senses is a very human way of inviting people to participate in the story of our built environment.

What do you think the future of how cities and humans communicate with each other is, “beyond the kiosk”?

Oliver Schaper: There are elements of the city that that don't change — or they change very slowly. On the other end we have real-time sensing data through digital twins. And then there’s a lot of stuff in between. I think the question is whether or not it's of value to have moments within the city that intuitively communicate these fast-changing elements of the city, because the slow changing ones are analog, and we can grasp it. I think it would be interesting to find the appropriate way to communicate real-time information as it is relevant without information overload. The above-mentioned boundary layer of the public realm becomes a canvas through which a new way of urban storytelling can occur.

Emilie Baltz: I like to imagine the future city as a portal, a series of thresholds that reveal invisible worlds hidden between, and within, our daily lives in a more imaginative way than two dimensional screens, signage, and charging kiosks. What if our technology was softer, more integrated into the built environment, so it truly could support rather than distract us? What does that form look like? What does the engagement feel like? Those are all questions that begin opening new possibilities through design.

For media inquiries, email .