- Products

- Pricing

- Solutions

-

-

By Use Case

- Digital Customer SuccessScale effort and align teams using digital-led strategies.

- Gainsight CS for SAP Sales CloudTransforming how businesses drive retention and growth within SAP Sales Cloud

- Gainsight EssentialsEssential features and onboarding to help you start and scale with Gainsight in as little as two weeks.

- Scale and EfficiencyDeliver outcomes without adding headcount.

- RetentionPredict churn and address risk.

- ExpansionIdentify and align on expansion opportunities.

- Product AdoptionProactively guide users to value.

-

By Team

- Customer SuccessEmpower and enable your CSMs.

- ProductCreate elegant product experiences.

- Customer ExperienceIdentify trends across the customer journey.

- Revenue and SalesDrive a high performing renewals process.

- IT and AnalyticsConsolidate your Customer Data.

- ExecutivesAlign on customer health and opportunities.

- Community TeamsBuild a modern customer community.

-

-

- Customers

- Resources

- The Latest from GainsightWhat’s new? From blogs to webinars, to guides and more.

-

-

The Latest from Gainsight

- Resources Library

- Gainsight Blog

- Upcoming Events and Webinars

- On-Demand Webinars

- Gainsight Glossary

-

Gainsight Pulse

Pulse isn’t just a conference—it’s where innovation meets community. The largest gathering of professionals dedicated to sparking revenue growth, building real connections, and turning ideas into action. Ready to put customers at the heart of your strategy? This is the place.

Check it Out- By TopicWe’ve got it all organized by Product, Customer Success, and Community.

-

-

Gainsight Pulse

Pulse isn’t just a conference—it’s where innovation meets community. The largest gathering of professionals dedicated to sparking revenue growth, building real connections, and turning ideas into action. Ready to put customers at the heart of your strategy? This is the place.

Check it Out- Customer ResourcesFind the Gainsight community, certifications, and documentation.

-

-

Gainsight Customer Communities

Create a single destination for your customers to connect, share best practices, provide feedback, and build a stronger relationship with your product.

Check it Out- Industry ResourcesFind a job, discover Pulse, and learn what’s happening industry-wide.

-

-

Industry Resources

- Customer Success Job Board

- Pulse Plus

- Pulse Conference

- Pulse Library

-

Gainsight Pulse

Pulse isn’t just a conference—it’s where innovation meets community. The largest gathering of professionals dedicated to sparking revenue growth, building real connections, and turning ideas into action. Ready to put customers at the heart of your strategy? This is the place.

Check it Out- Essential GuidesIf it’s here, it’s essential knowledge on CS, PX, and community.

- Company

- Impact

- Login

- Schedule a Demo

- Essential GuidesIf it’s here, it’s essential knowledge on CS, PX, and community.

-

- Industry ResourcesFind a job, discover Pulse, and learn what’s happening industry-wide.

- Customer ResourcesFind the Gainsight community, certifications, and documentation.

- By TopicWe’ve got it all organized by Product, Customer Success, and Community.

-

-

- The Latest from GainsightWhat’s new? From blogs to webinars, to guides and more.

- Products

- Pricing

- Solutions

- Customers

-

Resources

- The Latest from Gainsight

- By Topic

- Customer Resources

- Industry Resources

-

Gainsight Essential Guides

- Quarterly Business Reviews (QBRs)

- Customer Success

- Voice of the Customer

- Customer Success Management

- Customer Journey and Lifecycle

- Professional Services Success

- High Touch Customer Success Management

- Company-wide Customer Success

- Recurring Revenue

- Channel Partner Success

- Product-Driven Customer Success

- Churn

- Budgeting for Customer Success

- Product Analytics

- Customer Experience

- Business Metrics

- Choosing a Customer Success Solution

- Product Management Metrics

- AI For Customer Success Managers

- Customer Education

- Company

- Impact

- Login

The Essential Guide to

Recurring Revenue

There are all kinds of ways to make money in business. You can sell a good or a service for cash straight up. You can rent your assets for a limited time and a lower price. There’s investment, banking … each one of those arrangements has upsides and downsides for both parties. When you sell your goods or services, you can make a great margin—more than you could if you were renting it. But it’s a one-time transaction. You don’t get your goods back to resell. You don’t get your time back. You can make a lot of money on the deal but maybe not as much as you could over a longer period of time. But if you were to rent your asset, you’re also out that asset for the duration of the period you’re renting it. You’re responsible for the wear and tear. You get a smaller return in the short term than a sale, but maybe you can make more over the life of the asset.

And we haven’t talked at all about the other party in these transactions. Buying something outright is great because that product is yours. It might cost more upfront, but you won’t pay more later—except if it needs upkeep or service. Then you’re on the hook. But you don’t need to pay for service or upkeep if you rent, but you also aren’t getting any owned asset back for your money. You can’t resell it, and you might pay a lot more if you need to rent for a long period of time.

But there’s another business model that has evolved into the dominant form of transacting in several industries alongside the technology that has made it possible. The subscription economy used to be about magazines and utilities, but it’s spread into markets not thought possible as recently as 10 years ago. The possibilities offered by this business model can have incredible upside for the vendor, the customer, and even the environment. In this essential guide, we’ll learn more about those benefits, as well as everything you need to know about how to calculate and optimize recurring revenue in your business.

Chapter 1

What Is Recurring Revenue?

If you zoom out on the term “recurring revenue,” it sounds like it’s the monetary value of any transaction that happens more than once. Under that definition, it’s simply any money a customer pays a vendor after the first transaction. It could be you filled up with gas at a specific station on your drive from Phoenix to Los Angeles, and then you filled up again at the same gas station on the way back. Technically that could be called “recurring revenue,” but there’s a bit more of a specific connotation with a key difference that will set the terms for this essential guide going forward.

Recurring revenue is the money a company can reliably predict it will earn from regular, stable transactions in the future.

That means our gas station stop on the way back from L.A. doesn’t count since we could have stopped at any gas station or not stopped at all. But the fuel company that sells its gasoline to that station on a regular basis (once per week, or month, or however often) would consider that revenue to be true recurring revenue.

Even if I have a measure of brand loyalty to whatever gas station I choose, if my refueling isn’t regular enough to be predictable to the vendor, my one-time purchase wouldn’t be considered “recurring revenue.” In fact, under this definition, most one-time purchases shouldn’t be classified as this type of revenue.

There are several different kinds of recurring revenue. Generally speaking, here are the three most common in business:

Subscription Revenue

In this type of recurring revenue, the customer pays in advance for a product or service to be used during a given period of time. The subscription renews automatically at the end of the payment period unless canceled. An operationalized renewal with the expectation of recurrence is what sets this apart from a rental, which is expected not to recur. If you rent a car, the car rental agency expects you’ll bring it back—extending the period of your rental is the exception. The agency may have already rented the car to another customer based on that expectation! On the other hand, there are a growing number of subscription car services meant to replace buying or leasing for some consumers.

Long-Term Contracts

Many companies sell their offerings on a contractual basis. You may pay month-to-month, but you’re bound for the length of the contract you agreed to, whether it’s one or two or more years. It may be possible to end the contract prematurely, but that will come with penalties. Likewise, the contract may include stipulations or costs the vendor agrees to pay or meet. Contracts do not typically renew automatically, which means there’s an opportunity for either party to extend, revise, or decline the terms of their business. We’ll talk more later about calculating contract values as recurring revenue.

Supplementary Purchases

This is another growing category of recurring revenue, yet it’s likewise a pretty old business model. It’s predicated on a (relatively) significant initial one-time purchase that will often be discounted to some extent that’s supplemented by regular purchases of accessories or disposable goods required to get value out of the initial expenditure. We’re talking about things like k-cups for single-serving coffee makers, replacement blades for shaving razors, and (infamously) Juicero.

Chapter 2

What Are the Benefits of Recurring Revenue?

As we teased in the introduction, the recurring revenue business model has a few advantages over one-time purchasing and renting for both vendors and consumers—although depending on how you do it, all these advantages can be limited, eliminated, or made a whole lot worse. We’ll talk about some of the pitfalls here too.

Benefits for customers

The principles of supply and demand have created a pendulum of equilibrium between buyer power and seller power over the long history of markets. Sometimes buyers have the advantage, in which case prices tend to be lower. Sometimes sellers have the advantage and prices are higher. There’s no doubt that the move toward subscription services to replace one-time purchases has empowered the customer. Let’s examine why.

When supply is less than demand, prices are high. And it’s the scarcest resource that limits the supply. In a manufacturing economy, that scarce resource could be a raw material, skilled labor, or component parts. But as our economy increasingly shifts toward digital production and automation, those scarce resources are becoming less and less determining factors, as Geoffrey Moore writes in The Manufacturer’s Dilemma.

There are no raw materials or component parts for pure software, and once it’s shipped, the only labor necessary is for whatever continuing support it needs—which naturally lends itself toward a recurring revenue business model. But the side effect is this: supply is infinitely greater than demand. In other words, the scarcest resource is the customer.

We’ve seen these benefits play out in a few concrete ways:

- A greater variety of choice in key markets like software.

- Disruption of long-standing business models like manufacturing.

- Lower friction to switching vendors to competitors.

- Greater flexibility in terms of pricing.

Benefits for vendors

When we talk about the power shifting to the consumer, that makes it sound like businesses are screwed. And the truth is many have been. Retail, manufacturing, infrastructure—all have seen heavy losses in the last two decades if they’ve been unable to adapt to the changing economy. But businesses that have been able to understand and evolve have had several advantages.

When you understand that your scarcest resource is the customer, it pushes you to optimize your business around protecting that “resource.” Let’s take a second to make clear that thinking about customers as an “asset” or a “resource” sounds a bit dehumanizing—they’re people, obviously. In fact, protecting your customers means recognizing and treating them as valued individuals—as humans.

Companies that recognize customers are the most important thing have managed to thrive in the recurring revenue economy. There are several aspects to it:

- Recurring revenue is extremely predictable.

- The lifetime value can be greater over the long term than a one-time purchase.

- Deeper relationships between vendor and customer lead to better outcomes.

- Successful customers can drive new revenue through advocacy and expansion.

Hazards for customers

If you have a recurring revenue relationship you’re unhappy with, why do you stay? The answer is most likely that you’re trapped in the relationship. While market forces have driven competition up and friction down, many companies have responded by trying to increase the friction to leave. There are a lot of great ways you can give customers incentives to stay, but one of the most common complaints in this new recurring revenue economy is that some companies have made it infuriating to leave. This is most often the case in industries with a lack of competition—like Internet Service Providers, Telecoms, mobile operating systems, etc.

Read more about the consequences of your customers feeling trapped in the Essential Guide to Customer Experience.

Hazards for vendors

As we’ve reiterated, the chief hazard for for recurring revenue companies is the low barrier to entry/exit—we call it churn. There are all kinds of downstream effects beyond just the loss of your revenue, too. Even if you’re growing in new logos, your churn rate can drag down your overall growth. In most subscription businesses, the Cost of Acquiring a Customer (CAC) is high compared to the short-term revenue rewards. The payoff comes months or even years after the deal is closed. We’ll talk a lot more about that in later chapters. Furthermore, churned customers tend to be detractors—they leave a bad review online or generate negative word of mouth, which can harm your sales & marketing efforts. Lastly, they’re a dead end for cross-sell and upsell (obviously), which is a major drain for “land and expand” companies.

Chapter 3

How to calculate recurring revenue

Recurring revenue—like any kind of revenue—is a number. But just as there are multiple types of recurring revenue, there are multiple ways of calculating it mathematically. There are component parts to the equation and some of these are more useful to certain businesses and less useful to others. We’re going to take a look at all the various revenue metrics in the subscription world and understand how to calculate them in this chapter. We’ll also talk a bit about what they mean for your business.

Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR)

How much money do you make in a year? This is a simple number: it’s the total dollar value of revenue earned from a customer in a year. You can also use it to refer to the total dollar value of revenue from ALL customers in a year. The one wrinkle is the contract value. If you have a two-year contract with a customer worth $10 million, that customer’s ARR is $5 million.

Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR)

Some companies renew monthly rather than yearly. You see this more often in smaller, self-serve models as opposed to big B2B enterprises. It’s the same as ARR, except instead of a year, it’s a month.

Gross Retention

Gross retention, sometimes styled as Gross Retention Rate (GRR), is the percentage of renewed dollars over a defined period of time. The maximum is 100% if you renew every dollar of recurring revenue during that period. This number doesn’t include cross-sell or upsell. You can calculate this by dividing the number of dollars renewed during the given time period by the total number of dollars able to be renewed.

Renewed dollars / Renewable dollars

So if you renew contracts worth $4 million out of a possible $5 million, your GRR is 80%.

Net Retention

This is the same as gross retention (it can even be referred to as Net Retention Rate (NRR)), except it does include the number of expanded dollars, whether through upsell or cross-sell, so the maximum can be over 100%. You can calculate this number by adding the dollars of renewed and expanded revenue together, then dividing by the number of dollars up for renewal.

(Renewed dollars + Expansion dollars) / Renewable dollars

Let’s say you renew $4 million out of a possible $5 million, but you also sold $2 million in upsell and cross-sell. Your NRR is 120%.

Which metric should I optimize for—NRR or GRR?

An excerpt from The Right Financial Metric for Customer Success: Gross Retention or Net Retention? by Nick Mehta

At first glance, it’s tempting to automatically assume NRR is the better indicator because it synthesizes two revenue streams—the renewal and the upsell. In a nutshell, it includes more information. But that’s not necessarily the case.

On one hand, GRR has an advantage over NRR in that it truly measures the long-term health of the business because gross churn erodes expansion opportunity over time. In other words, you can’t upsell clients that you lose!

On the other hand, an over-focus on gross retention and churn can lead to a point of diminishing returns.

And this focus has practical effects every day. Do I focus on the nth at-risk client and trying to save them (sometimes in futility) or take that energy and spend it on a healthy client ripe for expansion?

3 Dimensions to the GRR vs. NRR Problem

There are a few core dimensions to consider in this problem:

- Financing: Are you private and needing to raise additional capital? In that case, investors may scrutinize your GRR. Alternatively, are you public or do you plan to go public? In that case, you likely will be reporting NRR.

- Growth Rate: If you are growing fast and valued on growth, NRR may have a larger economic impact near-term. On the other hand, slow-growth companies can receive great ROI from optimizing GRR (and therefore churn).

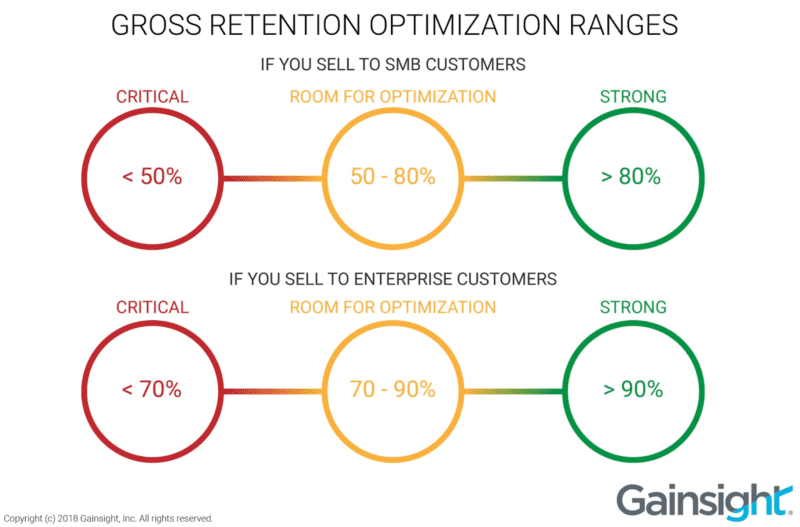

- Current Gross Retention: In general, there is a bright line for GRR and you don’t want to go below it. Depending on your target customer segment and Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC), that rate could be below 60% (for SMB) or below 70% (for Enterprise). Below a certain point, investors look at a business as being not viable, and the churn rate indicates more fundamental, systemic challenges.

It all comes down to how optimized you are around Gross Retention—or to put it another way, how optimized your renewal mechanism is. If that mechanism fully optimized or very efficient, the higher-ROI focus might be around Net Retention. My recommended GRR ranges are:

So Do I Optimize for GRR or NRR?

If you’re a private company needing more capital, I would work hard to get your GRR to the Fully Optimized level, since investors will notice. If you’re public and reporting NRR, you can probably live in the zone of “Room for Optimization” for GRR and focus on improving net retention. Similarly, the higher your growth, the more you should focus on Net Retention versus Gross Retention.

It’s certainly a continuum, but if you’re a high growth public company with a 97% GRR, you might take those incremental hours spent chasing the pesky few RED customers and instead double down on your successful ones to help them grow and expand.

Customer Lifetime Value (LTV)

Customer LTV or CLTV is really the “holy grail” of financial metrics. It’s the ultimate goal of the recurring revenue business model, even though it’s not something you’ll look at very often from an operational perspective. That’s because it’s the quintessential lagging indicator. You want to maximize it, but tracking it won’t give you any insight into what you need to do to achieve it. That being said, it’s helpful to look at for a sense of how your recurring revenue compounds over time to validate your investment and understand your most successful customers. Calculating LTV is simple.

Average Transaction Value X Average Retention Time X Number of Transactions

So a customer who spends an average of $100 per renewal every one month (on average) for four years (48 months) has a CLTV of $4800.

Cost of Acquiring a Customer (CAC)

We’ll talk more about these next two in the next chapter, but let’s quickly understand what they mean and how to calculate them. CAC is simply the total amount of sales & marketing spend divided by the number of new customers during a given period of time.

Sales & marketing / Number of new customers

If you spend $1 million a year on sales & marketing staffing, programs, and operations, and you book 100 new logos during that year, your CAC is $10,000.

Cost of Retaining a Customer (CRC)

It’s the same idea here, except instead of sales & marketing, you need to combine the spend for all your retention-related operations, programs, and staff. This could include Customer Success Managers and technology, Account Management, Onboarding, and more. Divide all that by the number of renewed customers and you have your CRC.

Retention costs / Number of retained customers

We’ll use the same example above. $1 million on all costs budgeted for retention results in 100 renewed logos equals a CRC of $10,000.

Click here to use our simple, online Customer Success Metrics Calculator.

Chapter 4

Expensive Revenue and Lean Revenue

We talked earlier about CAC versus CRC and how they’re calculated. But we used the same example equation for both. The reality is that the cost of retaining a customer is often much lower than the cost of acquiring the customer. But even that doesn’t tell the whole story. Most companies tend to be hyper-focused on new customer acquisition. But in a recurring revenue model, customer retention is equally—if not more important. That’s because new revenue is expensive, but retained revenue is lean. Let’s look a bit closer.

Expensive Revenue: Revenue from new clients. This is very unprofitable initially due to cost to acquire the clients. Furthermore, we can break this down into two types:

- “Good” Expensive Revenue may be initially unprofitable, but worth the long-term investment.

- “Bad” Expensive Revenue will never become profitable. It’s your Customer Success Executive’s job to spot these deals and notify your Sales team.

Lean Revenue: Revenue from existing clients. This is where the profit comes from in most companies, and can include:

- Deferred Revenue Recognition: In SaaS specifically, companies often bill customers upfront for a period of time (e.g., a year), but then typically recognize that revenue evenly over the ensuing periods. Since most of the cost is incurred upfront, the ongoing revenue that was deferred upfront and recognized over time is very profitable.

- Unbilled Deferred Revenue Recognition: Furthermore, SaaS companies with multi-year contracts often bill one year at a time, meaning profitable revenue will “automatically” show up in future periods that isn’t even on the balance sheet today.

- Renewal of Existing Customer Agreements: Typically, customers purchase SaaS offerings with the intention to use them for a long period of time. If the SaaS vendor is good at customer success, they can drive high renewal rates on those contracts with a lower cost of renewal than the cost of the initial sale.

- Expansion of Those Agreements: Finally, those customer agreements can grow over time with limited incremental Sales & Marketing expense.

The advantage is clear, but many companies fail to capitalize—either due to financial restrictions like an overly simplistic profit & loss (P&L) or organizational oversights (no one is responsible for the lean revenue; it’s all just “Sales”).

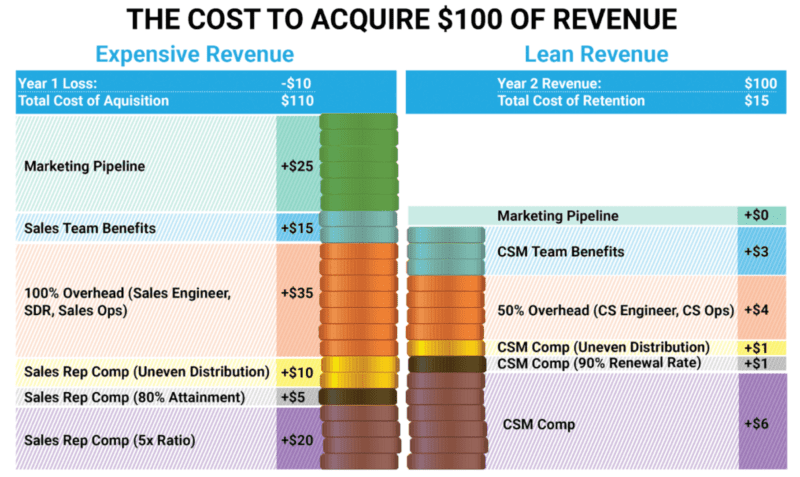

We’ll do a little exercise to contrast them. Let’s imagine $100 each of expensive and lean ARR. Please note for the purpose of this exercise, We’re not including the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS), which could include onboarding, support, product customization, and more.

The Cost of Acquiring $100 of Expensive Revenue

The costs to acquire $100 of expensive revenue include base salaries, benefits, and overhead for your Sales team (sales reps, sales engineers, management, sales development reps, sales ops, etc.) plus commissions (let’s say 9%—the average from the latest Pacific Crest data).

One way to think about those costs is to look at the ratio of base salary and commission (together called “On-target Earnings”) for sales reps versus their target quota (OTE/Quota). Many companies target five times or more in this ratio. For example, a sales rep at $220K OTE ($110K base, $110K commission on-target) at a 5X ratio would have a $1.1 MM quota. At full attainment, this means $20 on the $100 of ARR would go to sales rep compensation, but most companies don’t hit 100% attainment versus quota. If you assume 80% attainment, you now spend $25 on the $100 of ARR.

And it’s worse still if attainment isn’t even (as in, one rep beats quota and hits “accelerators” while another misses). Your rep cost creeps up to $35 on the $100 of ARR. Now add in the cost of the sales engineer, sales development rep, and sales ops resource (along with management) and your $35 turns into $70 easily. Add in benefits and $70 turns into $85. And this doesn’t include the cost of “unramped” sales reps, which could make the numbers even worse!

Finally, how can Sales sell without any leads to sell to? Depending on the company and business model, companies might spend $25 to $100 on marketing for every $100 in ARR. The hypothetical example I’m using now is likely skewed towards a sales-heavy business model, so let’s assume $25. And now you are at $110 total to acquire $100 of new revenue.

Just like that, you need at least a year to payback revenue. And this isn’t counting the impact of gross margin—if you look at the time to recover the $110 in gross margins and assume 70% gross margins, your payback period is now almost 19 months. You might be getting paid upfront from your clients, but many businesses offer multiple payment plans, delayed payments, etc.

So now you can see why acquisition burns a lot of cash!

The Cost of Acquiring $100 of Lean Revenue

Now let’s look at the costs to acquire $100 of lean ARR. Those are costs like base salaries, benefits, and overhead for your CS or Renewals team (CSMs, Renewal Managers, Account Managers, Customer Success Operations, Customer Success Architects, Team Leaders, etc.), as well as commissions for those same team members (2% on average for renewals and 8% for upsells, according to the same recent Pacific Crest survey).

Let’s note that Support team members typically fall into COGS, which is a different cost set altogether.

As with Sales above, we can look at the ratio of OTE for team members versus their target quota of renewal/expansion ARR. At scale, most CSMs/AMs cover more than $2 million of ARR (and sometimes $5 million or more)—that’s a lot more than your average sales portfolio. Furthermore, their OTEs tend to be less ($100K to $150K) than their Sales counterparts. At full attainment, this means $6 on the $100 of ARR (assuming $120K OTE) would go to compensation. And while most companies don’t hit full quota for renewal/expansion, the attainment percentage is likely a lot higher than sales, so let’s use 90%, meaning you’d spend about $7 for every $100 of ARR.

Renewal and expansion compensation plans typically don’t have the same accelerators as sales plans so you don’t get penalized from an uneven attainment—and attainment is likely more even by default. So let’s assume $8 now. The overhead for this area is much less. There are fewer technical resources and no SDR equivalent, so let’s use a 50% overhead, or $12. Add in benefits and you’re at about $15.

And the best part is there are no marketing costs required! All of this aligns pretty well to the Pacific Crest survey data, which shows companies spending $0.12 per $1 for renewals (or $12 per $100). Maybe we were a bit conservative with our exercise!

Obviously you need to invest in acquiring a new customer before you can renew it, but when it comes to where the real profit center of your business is, in the recurring revenue system, the answer is right in front of our faces:

And the ceiling isn’t 100%

It’s easy to understand the math above and still make an analytical error in subconsciously assuming that Lean Revenue is fundamentally capped. Remember, we’re talking about net revenue here—not gross. There’s a ton of additional revenue potential in your existing customer base:

- Additional users, seats or licenses

- Additional product

- Additional services

- Plain old price increases

Let’s look deeper at these in the next chapter.

Chapter 5

How to Grow Recurring Revenues

The standard way of thinking about operationalizing revenue is as a pipeline of handoffs. How do you manage handoffs from Marketing to Sales Development, from Sales Development to Sales Reps, from Stage A to Stage B—as quickly as possible, at the highest price, as predictably as possible.

But a straight and narrow pipeline doesn’t mesh as well with this new world of recurring revenue. In a recurring revenue business model, leads are the start AND end of the pipe. When you demonstrate to a customer that they’ve achieved a financial return on their purchase, you’ve created at least three new leads:

- A lead for a renewal event: This customer is prime to be renewed.

- A lead for an expansion deal: This customer will be amenable to get even more value from their partnership with you. In fact, there may be multiple expansion opportunities.

- A lead for a new logo: This customer will be happy to speak to a prospective customer about the value they’ve achieved. In fact, they’ll be willing to speak to multiple prospects.

If you make your customers successful, you can turn one new lead into three or more leads. And in turn, those three incremental leads result in 3 x 3 = 9+ new leads. And those 9+ leads result in 9 x 3 = 27+ new leads. That’s exponential growth.

The growth pattern of successful recurring revenue companies resembles an expanding Helix: the successful customer brings you back to your starting point (leads), but your company is increasingly better off than it was before.

The Helix Model of revenue growth

As we talked about earlier, companies often view their revenue internally as a series of handoffs. This reflects a very “siloed” vision organizationally. In this vision, Sales argues with Marketing over the quality of the leads, Marketing argues with Product over whether there was enough “demo ware,” Product argues with Support over what’s a bug and what’s a feature request.

But in order to achieve this helix level of exponential revenue growth, every department needs to work across the customer lifecycle. Here’s what this means for the departments that are aligned to revenue:

- Sales: Driving deals at every point on the customer’s journey. They’re closing new logos, renewals, and expansions.

- Marketing: Driving pipeline at every point on the customer’s journey. They’re finding new leads, finding expansion leads, and finding customers who will generate new leads.

- Customer Success: Driving value at every point in the customer’s journey. They’re holding value workshops and planning discussions during pre-sales, they’re defining value workstreams at the kickoff call, and they’re demonstrating value attainment during Executive Business Reviews.

Therefore in this model, each department has a new charter, and each department’s success is measured differently from before. How is each team contributing to the three revenue events: new logo, renewal, expansion? Here are some proposed target metrics:

| New Logo | Renewal | Expansion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sales | New Logo ARR | Renewed ARR | Expansion ARR |

| Marketing | Marketing Qualified New-logo Leads (MQNLs) | Marketing Qualified Renewal Leads (MQRLs) | Marketing Qualified Expansion Leads (MQELs) |

| Customer Success | Customer Success Qualified Advocacy (CSQAs) | Customer Success Qualified Healthy Customers (Habits Scorecard) | Customer Success Qualified expansion Leads (CSQLs) |

Chapter 6

Revenue Operations Tactics

Let’s look at eight playbooks for operationalizing revenue growth in the helix model.

Lead: Enable and incent post-sales teams to create leads

Everyone who interacts with the customer should be a source of leads.

Create a set of triggers for support, professional services, training, and CSMs (if you have them) to help them know when it’s time to send a lead to Sales. Make the process streamlined so it results in a new “lead” in your CRM for the sales rep—as if it came from Marketing. Incent each team member with a simple and transactional reward system.

Opportunity: Put healthy references in front of sellers in real-time

Many companies build marketing reference teams and a complex process for reps to get references from Marketing. While this can be important for key references, the most valuable references are the ones that are “name-dropped” in real-time on a first call between a rep and a prospect. However, the death knell for any deal is “name dropping” a reference that’s actually unhappy, so lots of reps don’t even try.

One of the biggest values of customer success is to provide actionable information for Sales. Sales reps should have a list of happy, referenceable clients related to their prospects in real time in their CRM.

Close: Capture desired client outcomes at deal closure

Reps have the most critical information in their heads right as they move the Opportunity to Closed Won in Salesforce – why the client is buying. Make sure that is captured in a Success Plan at deal closure. Not only will this help the Onboarding and CSM teams, but also it will help the rep nail the future Executive Business Reviews to realign with the exec sponsor and drive renewal and up-sell. Come up with a structured and streamlined Success Plan template – integrated into Salesforce.com – to make the hand-off seamless.

Onboarding: Survey customers 30 days after sale and incent reps on answer

At the end of the day, helix revenue is driven by closing high quality deals. Sales teams want to bring on customers that will stay and grow—with the right expectations up front. But how can you understand that quality and set those expectations? Survey new clients 30 days after Closed Won and ask the client a simple question: “On a scale of 1-5, how well did [sales rep] set your expectations in the sales cycle?” Don’t hold the sales rep accountable for the whole experience; hold the rep accountable for the expectations. Make this a carrot incentive and pay out a bonus for every 5/5 survey.

EBR: Crush your EBR with a success plan, white space, and a killer deck

The funny thing about “Executive” Business Reviews is they often don’t attract or impress “executives” at clients. They are frequently poorly-organized and very tactical. Change this by having:

- A standard playbook for accountability in an EBR between the rep, CSM, and others.

- A Success Plan (captured from the sales cycle) that you can use to frame the meeting around the client’s desired outcomes.

- A “white space analysis” beforehand showing what the client owns and is using—and what more they could benefit from.

- An automated process to produce the deck in a consistent, data-driven, and high-quality fashion.

Get even more EBR tactics in the Essential Guide to Quarterly Business Reviews.

Expansion: Jump on good moments when they happen to drive upsell

Customer relationships aren’t always great. They have their ups and downs. Great companies jump on the “up” moments to expand relationships. When a client gives you a 10/10 on an NPS survey, has a successful launch, has a great support experience, or shows high product activity, you need to be on it.

Operationalize a mechanism such that Sales can get engaged right away during every positive moment in the customer journey and track which ones end up yielding closed expansions.

Also, make sure you’re not blindsided by existing customer risk during this process. Make sure every rep has a full view of client risk (adoption, surveys, support, services, etc.) The worst thing you can do is call a client for an upsell during an escalation.

Renewal: Get ahead of sponsor risk

The number one killer of renewals is sponsor change. When you lose your sponsor at an account:

- Find out immediately (via social media, for example).

- Create a standard playbook with accountability between the rep and CSM.

- Craft a standard email template to reach out to the new sponsor.

- Send a gift basket for extra measure!

- Define a streamlined “re-introduction” deck for the new sponsor and automate it, if possible, to include a company overview, the history of the relationship and usage, value, and outcomes driven thus far.

- Don’t forget your former sponsor; follow them to wherever they go next (gift basket!) and generate a new lead in the process.

Watch the latest webinar on playbooks for sponsor change.

Automate: Get more high quality time by automating low value tasks

There are tons of recurring revenue-driving processes you can automate using technology, including:

- Reference lookup

- Desired outcome capture

- Routine email outreaches

- EBR preparation

- Call preparation

- Renewal notifications

Chapter 7

Using Gainsight RO to Optimize Revenue

Hopefully you’re convinced by now (as we are) that your existing customers can become your greatest source of revenue. That’s why we built Gainsight RO for Revenue Optimization. Gainsight RO enables Sales teams to drive growth through predictive analytics, streamlined renewal workflows, and whitespace analysis.

There are three vectors to Gainsight RO’s ability to optimize your revenue:

- Analyze and forecast renewals.

- Uplevel your strategy with data insights.

- Automate renewals at scale with best-practice playbooks.

Let’s look at them one-by-one.

Analyze and forecast renewals

Gainsight RO helps you forecast and manage your book of business with predictive renewal scores and real-time visibility into open and at-risk renewals to ensure a best-in-class renewal experience.

- Visualize open, closed, and at-risk renewals in one clean and easy-to-navigate UI.

- Generate and tweak renewals forecasts by using real-time, predictive likelihood-to-renew scores.

- Quickly analyze reasons for churn, identify gaps in data, and drill down into at-risk renewals.

Uplevel your strategy with data insights

Gainsight RO automatically alerts your team to upsell and cross-sell opportunities based on dimensions such as license utilization, sentiment, capacity, whitespace, and more so you’ll never again miss an expansion opportunity.

- Sell additional product and services packages by identifying current gaps.

- Use health scores and other essential customer data to inform tailored expansion conversations.

- Develop account plans to work cross-functionally towards expansion objectives.

Automate renewals at scale with best-practice playbooks.

With Gainsight’s orchestration capabilities, your team can drive personalized email offers about new features, products, and services to precisely targeted customer segments, ensuring you capitalize on every potential revenue opportunity.

- Trigger journeys to guide customers through an automated and personalized renewal process.

- Send email campaigns about new products and services to a targeted set of customers.

- Bring in humans at the right point during the renewal or cross-sell process to optimize headcount.