Nsio on DeviantArthttps://www.deviantart.com/nsio/art/Some-Old-Composition-Studies-1099556447Nsio

Nsio on DeviantArthttps://www.deviantart.com/nsio/art/Some-Old-Composition-Studies-1099556447NsioDeviation Actions

Badge Awards

Description

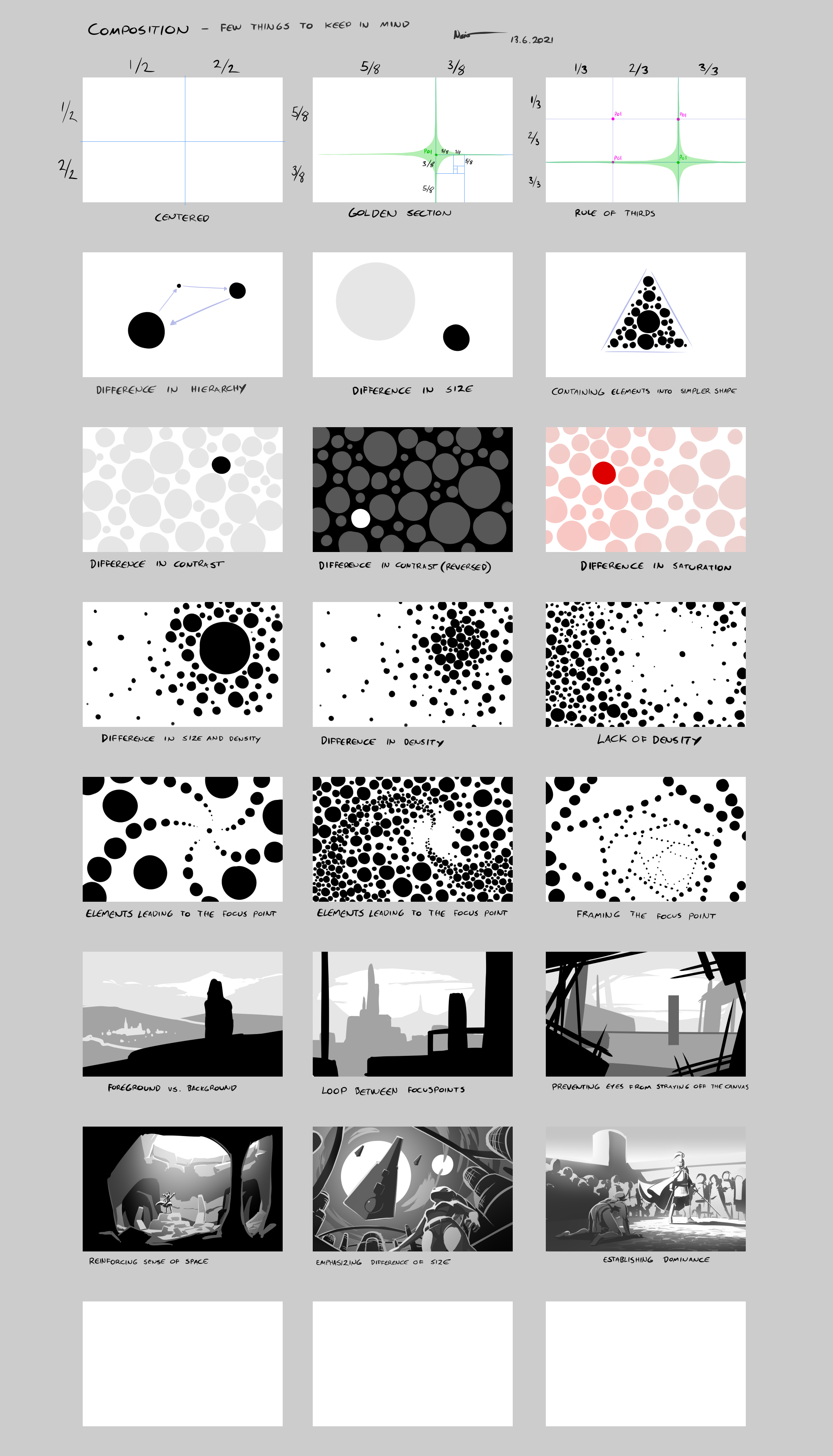

I drew these small composition diagrams about 3 years ago. There could be a lot more of different examples if only I wasn’t so lazy haha! But to be honest, it's surprisingly difficult to extract the core ideas of concepts like these when you haven’t personally paid a lot of attention on such details. I usually come up with the ideas during the practical drawing process rather than pondering the theoretical scenarios.

Composition in my view is mainly about making the eyes glide towards and around the focus point(s) with the least possible resistance. This is then reinforced by creating “differences in resistance” to push the eyes towards intended direction or making it less desirable to move them in some other directions, such as keeping the eyes of the viewer from wandering off the canvas.

The eyes are always drawing towards things that are different from the rest of the illustration. The way things differ can vary in many ways and levels. The eyes also likes when the important elements are positioned at certain places on the canvas.

The 1st row: Centered, golden section, rule of thirds

These are mainly about the common compositional rules that just “work”. The main idea here is to place the important element(s) along the lines and focus points on the spot where the guidelines cross each other. I haven’t put much thought on these, but you can’t really go wrong with the placement of elements if you stick to these rules.

“Centered” composition isn’t ideal, for it lacks the certain feel of dynamic tension the other two have. But this can work if there is nothing but, say, a character on a solid color background. If there is nothing around the subject you are drawing, then there isn’t much need for the composition either now is there? Anyway, this is an option, but it’s not something that’s “always safe” or “always working”.

“Golden section” is the old classic that just works wonders. I suppose its beauty lies on its mathematical proportions and how it divides the canvas in such a way that just ticks the right spots in our mind. There is this almost magical tension whenever something important is placed along the lines or at the intersection.

“Rule of thirds” is also very useful rule to follow. Here the canvas is divided in thirds which create a matrix of nine rectangles. I’ve mostly seen this utilized in photography. Again, the lines and intersections just have certain tension that feels good when elements are placed on them.

The 2nd row: difference in hierarchy/size and containing elements into simpler shape

A common way to differentiate focus points in an illustration is to vary their size. The larger the element, the more important it often is. The elements should not be equal in size with each other unless the point is to illustrate their equal importance. like Kira and L from Death Note for instance: when neither of them has the edge over the other, they are often portrayed equal in size.

The diagram in the middle practically about “size” overriding the “difference in contrast” on the next row. In short, the black circle is small but dark, so it pops out more from the white background. While the other circle is gray and thus doesn’t pop out quite as much, it’s much larger than the other. This works well with perspective which gives the gray circle epic proportions: the dark circle could be a hero at the foreground while the large gray circle could be a huge dragon at the background.

“Containing elements into simpler shape” basically means that the individual elements you draw form some sort of a shape together. The triangle is just a basic example.

The 3rd row: difference in contrast/saturation

The two diagrams on the left illustrates how seemingly similar or even smaller element pop out from the rest due to different contrast value, signifying a focus point in that particular context. While dark spot stand out from a sea of light elements, it also works the other way around.

Difference in saturation is a variant in which saturation plays an important role of marking the focus point, although in my example there is also high contrast difference.

The 4th row: difference in size and/or density, lack of density.

“Difference in density” in this context means how the elements form gradually denser cluster(s). The point is to create a gradient of low and high density area(s) which then signify the focus point(s). In the two examples on the left the denser clusters are clearly the focus points. On the third example, however, it’s the lack of density which defines the focus point.

The 5th row: elements leading to the focus point/framing the focus point

“Elements leading to the focus point” are just about arranging elements in such a way that the form paths that lead the eyes of the viewer towards the focus point. These paths work like magnets: they grab the wandering eyes and directs them towards the focus point. These can also be used to reinforce the sense of depth in perspective.

“Framing the focus point” does the same in a more roundabout way. The main point is to keep the eyes of the viewer from wandering out of the canvas edges but they can also gradually lead the eyes towards the focus point.

The 6th row: foreground vs. background, loop between focus points, keeping eyes on the canvas

These three are still quite abstract but begin to form more recognizable environments. These are common applications of the “difference in size and/or contrast”. The foreground is often darker while the stuff farther away are lighter.

There can also be multiple levels of value contrasts: in the first diagram, there lighter blotch within the gray area could be a city which forms a second focus point, making the eyes jump between the character at the foreground and the city at the background. Then, to make one part of the foreground more important than the rest, the head of the character could be framed with a lighter area to create higher value contrast between the character and the sky.

“A loop between focus point” is about creating a looping path for the eyes to glide on which naturally keep the eyes moving between the focus points. In the second diagram, the eyes are at rest within the white area. When ever they move anywhere else, the elements begin to create such resistance that the eyes just want to keep moving along the lighter area.

The third diagram is about framing the scene with dark foreground elements around the canvas edges. These create resistance that prevents the eyes from straying of the canvas. With so many diagonals, it’s like the eyes were ricocheting all around, making the rest of the canvas more peaceful and thus more comfortable for the eyes to stay on.

The 7th row: more concrete examples

My idea was to create several examples with more nuanced applications, but it was surprisingly hard to be imaginative enough. And I’m also somewhat lazy as I already mentioned.

Anyway, the first illustration is about sense of space. I drew a some sort of a cave with a large hole at the ceiling to provide a strong light source. The foreground has dark elements to frame the scene and keeping the eyes within the canvas. There is a character at the Golden section, who is both darker and lighter than her immediate surroundings, thanks to the light and shadow which differentiate her enough from the dark tunnels. The ground is also a bit lighter than the walls, making the eyes prefer staying around there more than on the dark walls. In case the eyes end up wandering to the bright sky at the top, the dark foreground elements are sure to make the eyes flow down back to the light ground and finally towards the focus point.

The second illustration is about emphasizing the difference in size. The buildings and the character indicate the viewing angle. The large vessel (most likely a star destroyer from Star Wars) against the bright circle (a planet or a moon) feels very large in the perspective context of the surrounding elements. There are also two other vessels indicating higher altitude. The clouds also form a circulating force which helps the eyes to move around in circular pattern when ever the eyes stray of from the vessel. The highways(?) also frame the focus point, preventing the eyes from straying of the canvas.

The third illustration portrays the difference in dominance hierarchy between the foreground and middle ground characters. Posing and body language is reinforced with light and shadow play: the subdued demon (it has horns, but they are a bit hard to see) is in the shadow while the dominant knight is basking in the light and details are discernable. The people at the background have less details and they are also less bright even if they are illuminated by the same light source to make the knight pop out. The walls and tower have practically no detailing. Together the people, walls and the sky form difference in density, drawing the eyes towards the denser area and then towards the two characters. The head of the knight is within the less dense area of the background to make it stand out even more. I recall my goal was to place the heads of the two characters according to the Rule of Thirds so that they occupy the opposite corners.

The 8th row: the void of nothingness

I never got to draw more thumbnails since drawing just these 21 diagrams was quite an endeavor, namely the last three.