Sharing stories

How reading, writing and drawing helped Kitty Wheeler after her friend's death

Sometimes when we are grieving, all we want to do is roll over and pull the covers above our heads. To do nothing.

I have learned that this doing nothing, is actually a big part of grieving. Being alone with our thoughts and feelings, starting to piece ourselves back together. All crucial for our healing. But this independent grieving can be lonely work. Often, we are told that we are not alone, but it is hard to feel otherwise sometimes.

So, how can we be alone with our grief without feeling lonely?

After my friend died of cancer, I found something that allowed me to be alone but feel supported and related to at the same time. Books. The days when grief stuck me to my bed, I would roll over, and pick up a book about someone else’s grief. Reading allowed me to quietly investigate my own grief without rejecting, ignoring, or forbidding it.

Other people’s stories help us feel less alone

Like many of us, I ignored grief’s presence in my life for a long time. It was only when many people started to die around me from coronavirus, that I realised what I had been feeling for my friend was grief. I was an English Literature and Creative Writing student, and in my second year, I tentatively embraced a module called ‘Writing Mourning’. I have since been fascinated with the infinite stories and research of other grievers, and how they express themselves.

At first, I couldn’t see how something as simple as books could begin to help my grief. Grief is something so big and painful, that we cannot hold or see. Yet I felt immediately inspired from holding somebody’s story in my hands, from the author’s bravery in sharing their grief with the world. The more books I read, the less alone I felt.

First, I came across Mourning diary by Roland Barthes. This is a series of his diary entries and study of grief after the death of his mother. I recommended the book to people who had lost their mothers, and they said that their grief became a little bit calmer, in the assurance that they were not alone. The more I read, the clearer I could see my own grief.

Some fantastic novels and memoirs about grief

- Grief is the thing with feathers by Max Porter (Wife)

- The year of magical thinking by Joan Didion (Husband)

- A monster calls by Patrick Ness (Mother dies from cancer, told through a child’s eyes).

- Mourning diary by Roland Barthes (Mother, study of grief via diary entries)

- A widow’s story by Joyce Carol Oates (Sudden death of a husband)

- The Guardians by Sarah Manguso (Friend)

- What we lose by Zinzi Clemmons (Caring for a mother dying of Cancer)

- Patrimony a true story by Philip Roth (Father to a brain tumour)

- Time lived without its flow by Denise Riley (Son)

Everyone’s grief is different, so, shouldn’t our expression of grief be different too?

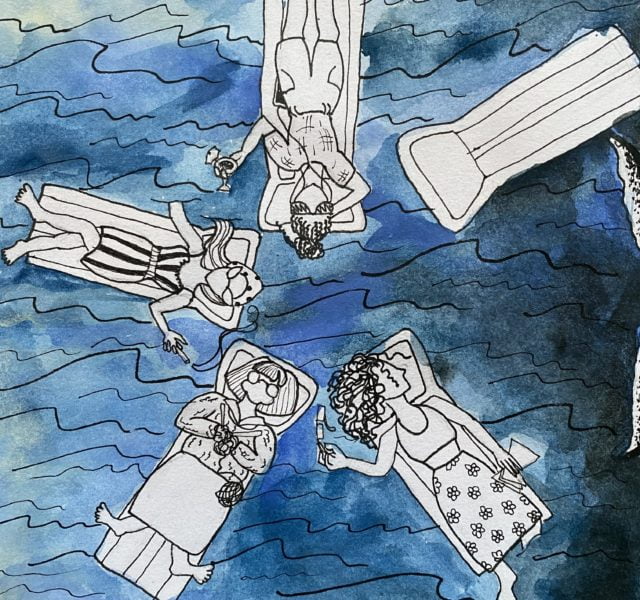

In my third year, I came across graphic books. Even as an artist myself, I had considered books with images to be for children or comic books. I was very wrong. Graphic books, particularly about grief, allow an extra door of meaning to be opened. Partly because images can be interpreted individually, but also because they can show what our words sometimes can’t. Broadly language is restricted, especially for grief, but images, never.

I have since experimented with the relationship between image and language to express the seemingly inexpressible.

The best part is you can do this too. You do not have to be Van Gogh to create a moving and cathartic picture. And you don’t have to be Shakespeare to write a story. Whatever you may make is yours. I have found art and writing to be a saviour in my darkest times. When I go to sleep, I acknowledge that grief still sits in my bones, but that I am making something special out of it.

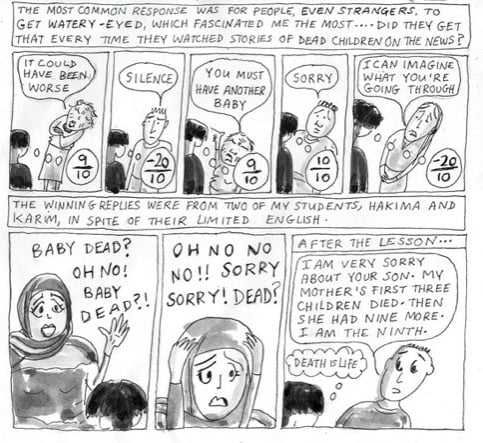

Billy, me and you

An example which demonstrates this transformation of grief into art, at its finest, is Billy, me and you by Nicola Streeten, about the death of her son. Her simple, scribbly, and sometimes witty images show all that needs to be said.

Streeton said: “I cried every day, for a year. In my memory, I only cried once. But it’s in my diaries, written down. Every day. I cried every single day, for a year. Looking back now, it’s clear we were pretty much mental for about five years.” She didn’t cry once while she was working on this book, though: “It’s the most pleasurable thing I’ve done, about the worst thing that’s ever happened to me.”

Some more wonderful graphic books about grief

- Billy, me and you by Nicola Streeten (Son)

- When David lost his voice by Judith Vanistendael (A family’s journey with cancer)

- The retreat by Pierre Wazem and Tom Tirabosco (Friends mourning a friend)

- The heart shaped bottle by Oliver Jeffers (Grandparent, good book for a parent to explain grief and death to child)

- Rosalie Lightning by Tom Hart (Daughter)

- Fun home by Alison Bechdel (Complicated relationship with father and his suicide, gender roles)

- Any book by Shaun Tan (Creative and whacky illustrations of creatures to help us see things differently)

Finding your coping mechanism

Maybe the idea of writing, reading, or drawing makes you want to shut off and shake your head. That’s OK too. You may try it and find it’s not for you. But something will be. I have only recently discovered how important it is to pour my grief onto a surface and investigate, mould, and express it. Just like we may go to the gym when we’re angry (or eat a full tube of pringles), or go to our favourite nature spot when we’re sad. We can look to other people’s stories when we are too tired to look at our own.

We sometimes look outwardly to help ourselves inwardly. And the best thing about books is that we can keep them as our secret if we want to. In our bags, on our shelves, and maybe with us under the duvet. So, we can escape to a different world for a bit, and come back to ours, and feel that little bit less alone.

Images below: extract from Billy me and you by Nicola Streeton; two illustrations from Kitty Wheeler, from the short novel she created for her third year dissertation ‘I Haven’t Cried Yet’. Kitty used whales to represent grief because they are an animal that grieves and often carries their dead through the ocean before they let them go.