Equity is the unit of ownership of your company. It has two features: economics and control. Economics is the financial benefit when your business performs well. Control is the influence an equity owner has on the future of your company.

Generally speaking, companies grant equity to three types of stakeholders: founders, employees, and investors. Stripe Atlas has written a guide on equity for founders; this one will focus on equity for employees.

This guide is most relevant for startup founders. Equity is a powerful tool to reward early employees for taking the risk of working with you (recruiting) and for motivating them on an ongoing basis (retention). Recruiting and retention are the two goals of employee equity and should always be top of mind when making a decision about an employee’s equity.

By the end of this guide, you’ll understand:

The definition of an equity plan and how to determine its size

How to handle employee departures or terminations in your equity plan

The three goals of vesting—and how to build an equity plan to support them

Ways to grant equity, and their advantages and disadvantages

The differences between ISOs and NSOs—and a common mistake to avoid

Recommendations from Pulley, based off of helping thousands of companies manage their cap table and equity

Pulley provides a top-rated cap table solution. Stripe is both a partner of and investor in Pulley. Experts at Pulley contributed their expertise to this guide (see disclaimer), and Atlas users can access more customized guidance directly from Pulley.

What is an equity plan?

An equity plan is a portion of your company that you plan to reserve for your employees. Shortly after incorporation when the value of your company is still low, you’ll typically promise early employees a certain percentage of the company (e.g., 1%). Think of equity compensation in terms of how much equity you’ll need to offer to close a hire. The tricky part about hiring with equity compensation is that equity is a finite resource and you don’t know which of your hires will end up being the best—and you want to use equity to reward performance, not a resume.

Although every company is different, startups that are pre-funding or have raised their first priced round typically land at the following benchmarks:

1-3% for key executives (e.g., VP of sales or VP of product)

0.5-1% for early ICs in technical functions (design, engineering)

0-0.5% for early ICs in commercial roles (bizops, bizdev)

Without an equity plan to define how many total shares are reserved for employees, the number of shares that you owe an early employee will fluctuate:

Founder A: 4 million shares

Founder B: 4 million shares

Employee 1: 1% = ~80,000 shares

If you were to give 1% to Employee 1, you might think that you need to give 80,000 shares, calculated based on the founders’ total—which until this hire, represented full ownership of the company. But that would make the new total share count 8,080,000 and the employee would own slightly below 1%. And with every new employee added, Employee 1’s ownership percentage would continue to fall, which turns your 1% offer into a false promise.

Instead, if you establish a plan and reserve 10% of your company for employees generally, the math looks like this:

Founder A: 4.5 million shares

Founder B: 4.5 million shares

Employees: 10% = 1 million shares

Now, your company has a grand total of ten million shares, and an employee equity pool of one million shares. If you give 100,000 shares to Employee 1, their ownership percentage—10% of the employee equity pool or 1% of the company—will not change with every new hire and you’re able to stay true to the offer you pitched them.

As you’re implementing an employee equity plan, there are two major decisions to get right: the size of the plan and what happens when an employee leaves.

How large should my employee equity plan be?

Startups typically create employee equity plans that comprise 10–20% of the total equity of the company, and the decision of how large to make the plan within that range depends entirely on your hiring needs. Founders are often coached into picking an arbitrary number in that range, but being more thoughtful about the number and how it can affect your cap table will save you an administrative headache.

The general logic is that the more skilled an employee base you need, the more equity you should set aside. If your startup is building rocket ships (in actuality—not 🚀), you probably need rocket scientists and engineers that are in very short supply and will demand a lot in compensation.

At Pulley, we haven’t seen nonfounder early employees receive more than 5% of a company, no matter how skilled or important, and we haven’t seen important hires (like a first designer or rocket ship engineer) at early-stage companies dip below 0.3%.

As a new company, you can’t pay strong salaries that an established multibillion-dollar business will pay, and you’ll need to compensate employees in equity to remain competitive in the hiring process.

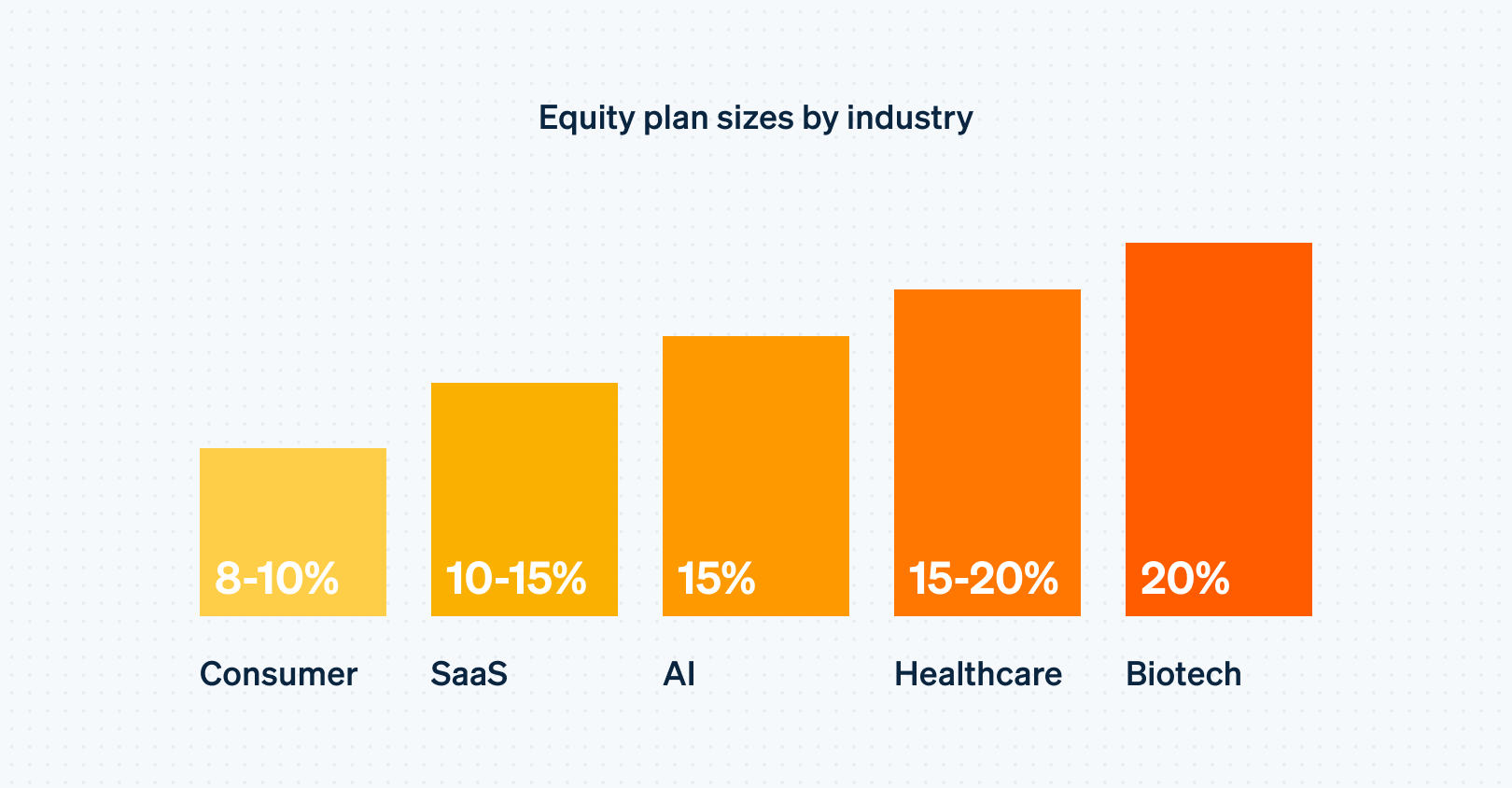

Conversely, at your early stage, you likely don’t have the time or resources to flesh out a fully fledged hiring plan or even have a reasonable idea of how much equity some of your key hires will expect. Here are a few benchmarks that we’ve gathered at Pulley for equity plans sizes, based on industry:

Keep in mind that what you should be aiming for is setting aside enough of an equity plan to get to your next financing round. When you raise money from investors, they will negotiate how big your employee equity plan should be once they complete their investment. Similar to when you created your equity plan right after incorporation, any equity given to employees will dilute the equity that everyone else in the company holds. Investors, of course, want to own as much as they are able to and will work to maintain a delicate balance: giving you a competitive edge in hiring while making sure to not dilute their investment.

How should an employee equity plan handle employee departures or terminations?

The next decision to make within your equity plan is on the set of rules governing what happens when an employee leaves the company. With resignation rates increasing, and disproportionately in the technology industry, this has become an even more important decision.

The legal terms for these rules are known as “post-termination exercise periods,” and, over the years, startups and their lawyers have had differing views on the best outcome. The goal of these time periods—whether 90 days or 10 years, for example—is to give an opportunity to employees to gather the cash needed to exercise their options. Otherwise departing employees forfeit unexercised options back to the equity pool so that they can be used by other employees.

It’s ultimately a question of fairness. How much time should a company allow its employees to gather cash needed to exercise, while not allowing too much time for employees to sit and wait to see if the company succeeds? Traditionally, these time periods have been 30–90 days to align with IRS regulations that change the tax status of certain options 90 days after termination.

More recently, startups have been split in three directions: (1) the traditional 30–90 day window, (2) a longer 10-year window, and (3) a variable window depending on employee tenure. For example, some companies add an extra month to exercise for every month worked. Coinbase and Pinterest have given a seven-year window to employees whose tenure exceeds two years.

Short windows require employees to have cash on hand to exercise almost immediately after quitting their job. Depending on how expensive exercising options will be, not every employee will have enough cash to pay for them on 30 or 90 days’ notice. This can create fairness issues. Some employees may be wealthy (and liquid) or be able to tap family or friends; some may be early in their technology careers and not have tens of thousands of dollars in their checking account.

Conversely, a 10-year window means that an employee can hold onto their options and wait a decade to see if your company succeeds. The employee will have more than enough time to gather the cash to pay for their options, but this benefit comes at the expense of your other employees. Models have shown that a 10-year window amounts to 80% incremental dilution for existing employees—while ex-employees hold onto their options, companies must expand equity pool sizes to make space for new hires. This adjustment solves for one dimension of the fairness problem, but creates an outsized benefit for departing employees instead.

A variable window—where the time period to exercise extends with tenure at a company—is less regressive than a 10-year window, but it presents the same problem. There will still be some employees that can hold options for an outsized period of time. For instance, companies may tie exercise windows to vesting, where employees receive an extra month to exercise for every month worked. In this scenario, employees that quit after a year have the opportunity to wait another full year before exercising, which is a relatively long time to sit on the sidelines and still benefit from the growth of an early-stage startup.

Years ago, large public companies like Coinbase, Pinterest, and Square changed from a traditional 90-day window to a 90-day window that increases to seven years after an employee works for two years. Although these companies set the tone for how later-stage tech companies address option exercising, it is largely moot now—none of these companies issue options frequently, but instead offer Restricted Stock Units, a particular type of equity award popular for companies at later stages (typically Series C, D, and beyond).

Unfortunately, a one-size-fits-all solution for post-termination exercise periods is not feasible because each employee’s financial situation is different. The simplest solution is to stick to a 30–90 day window for every employee, and make exceptions to the rule—which have to be approved by the board—for special scenarios where the employee needs more time to gather cash to exercise options.

Your aim should always be to maintain fairness—employees who quit shouldn’t gain a particular benefit over those who stay. For Coinbase, Pinterest, and Square, fairness meant rewarding employees who worked for at least two years. For a midstage startup with a large population of employees with lower salaries (such as a services firm with a high number of junior staff), fairness might mean a month to exercise for every month worked. And for a one-year-old startup, fairness might mean keeping exercise windows narrow to make the best decision for existing employees.

The proposed 30–90 day window with flexibility to extend can create a minor administrative headache because extensions typically must be approved by the board, but it is ultimately the fairest outcome for folks at early-stage startups because: (1) existing employees can take comfort knowing that former employees holding options won’t dilute their equity, (2) former employees are forced to make a decision with a financial hardship exception as needed, and (3) you as a founder can reinforce trust across the organization.

How and when should employees vest their equity?

The next major decision when granting equity to employees is vesting: deciding under which system employees will receive their equity over time.

For vesting, there are three goals:

Competitiveness in hiring

Fairness when employees quit early

Motivating and retaining talent

Competitive Vesting

Vesting is a competitive advantage in hiring. Companies that vest employee equity early create an incentive for employees to join by reducing the risk of leaving or getting fired before an equity grant vests.

For example, large tech companies like Lyft have moved to a one-year vesting schedule to speed up employee equity payouts. While this is attractive for public companies because they can pitch quicker liquidity to prospective hires, there are downsides to speeding up vesting. Accelerating vesting for employees typically means smaller grant sizes and a huge administration burden. Instead of a large grant that vests over four years, companies adopting a one-year vesting schedule will have to decide and execute on a smaller grant each year.

At the early stage, getting fancy with vesting is more effort than it’s worth because the burden is on a founder to explain why they are doing something nonstandard during the hiring process. An exception to this rule is senior management roles. If you are adding a C-suite role, such as a COO, CFO, or cofounder, spending time to offer candidates a bespoke vesting schedule can pay off. Think of spending your time here on a sliding scale: spend more time and energy (and dig into vesting) with critical candidates.

For the vast majority of employees at the vast majority of startups, there’s a great benefit to standardizing or following the pack. Remember that equity is only effective as compensation if the person receiving it fully understands how it works and why it could be a meaningful part of their compensation. Startup employees generally know how four-year vesting with a one-year cliff works, and minimizing the variables to their understanding of their compensation package is important in helping them realize the true value of your company’s equity.

Employees who quit early

Another consideration with vesting is to calibrate treatment of an employee who leaves quickly. Allowing an employee to gain the benefit of everyone else’s work in the company even if they only stayed for two months is unfair to the rest of your team.

This scenario led to the creation of a vesting “cliff,” which means that an employee doesn’t vest until they have worked for a certain amount of time, typically one year. For a four-year vesting schedule, this means 25% of an employee’s equity vests at the one-year mark.

Startups have remained remarkably consistent on one-year cliffs, and employees in the hiring market understand that startup equity comes with that commitment. For special cases, like a top employee leaving at the 11-month mark to start their own company, you can accelerate their vesting on a case-by-case basis to help them reach their cliff if necessary.

Use your discretion as the leader of a young company. There’s a lot of flexibility in equity grants. Start with the generic standard, then aggressively leverage your discretion to get the best outcome for each employee. This is a unique advantage for early-stage companies in a competitive hiring market. As you scale, this dialogue will naturally shift depending on the needs of your company and employee base, but it’s critical to start off by setting the right tone with equity compensation.

Motivating and retaining talent

Vesting is also designed to continue incentivizing employees to work hard. The traditional four-year vesting schedule gives an employee 25% of their grant each year, effectively incentivizing them to the same degree throughout their four-year vesting period. The counter-argument to the traditional schedule is that when employees are often most knowledgeable and empowered—in years three and four—there isn’t any added motivation for them to work harder than in their first two years.

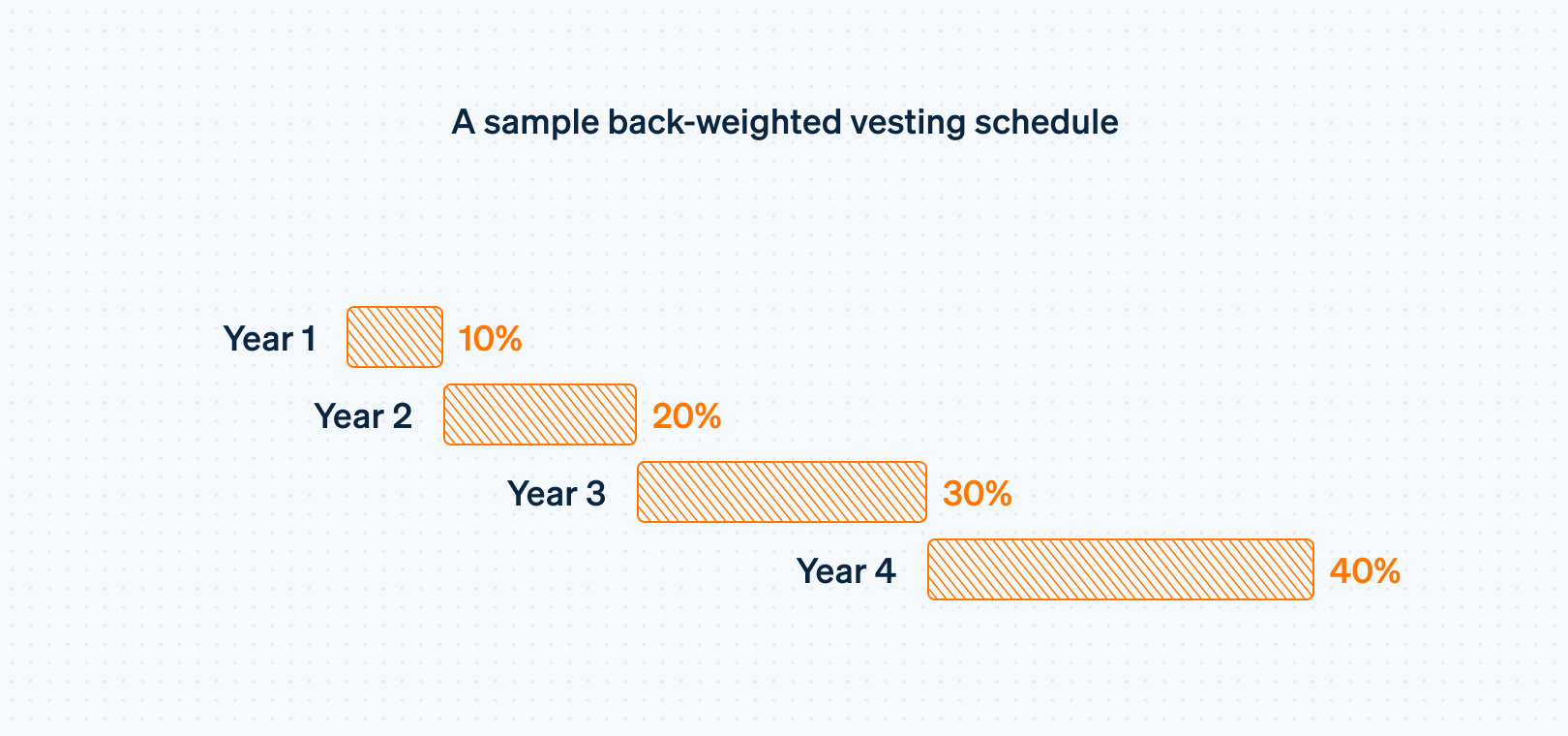

To solve this problem, companies like Amazon and Snapchat have started back-weighting their vesting schedule, which means that the employee vests proportionately more of their equity in later years. For example:

Although this solves the problem of motivating employees appropriately, it falls short as a recruiting tactic. By year two in a traditional four-year vesting schedule, an employee will vest 50% of their equity, while employees vest just 30% in the back-weighted vesting schedule.

For young startups, this is a nonstarter for prospective hires because there’s no guarantee that the startup will not get sold within that time period, in which case the employee loses out on their unvested equity. Large companies like Amazon or Snapchat do not carry that same risk because they are publicly traded with liquid equity.

The simplest way to solve this problem at the early stage is to continue granting equity to employees who have high potential or are performing well. Instead of one grant at hire, give top employees additional grants every six to twelve months so that they vest multiple grants at the same time. This approach increases the amount of equity high performers vest every year, while maintaining your hiring edge.

This vesting schedule is also the most practical answer. You can’t be certain which employees will be the best when you’re recruiting, and rewarding performance is a better motivator than rewarding someone for a great interview or resume.

What ways can startups grant equity?

There are two ways a young company can grant equity: stock or stock options. Stock is direct ownership in the company, whereas stock options give an employee the choice to buy stock in the company.

In both cases, your employees will actually receive equity over time depending on their vesting schedule, but with stock, the employee is treated as “owning” equity immediately, for tax purposes. In contrast, with options, the employee does not have any tax consequences until they decide to exercise.

The practical difference for an employee is that, with stock, they will have to pay taxes for the stock as they vest it, while options don’t require any upfront investment and give employees a choice of whether or not to invest in the company by exercising options.

Stock comes with two administrative hassles. The first is helping employees file an 83(b) election with the IRS—this filing reduces the employee’s tax burden by allowing them to pay taxes up front at a presumably lower rate than if they paid as the stock vests and gains value over time. The second administrative burden is buying stock back from an employee when they leave the company before they vest.

An 83(b) election is complicated but vital because the tax savings are material to the employee. Stock is only worth granting over options in large part because of the 83(b) election, and missing the 30-day deadline will result in a worse outcome for your employee than giving them options. Say an employee is granted 48,000 shares of stock, with each share worth $1. If a 83(b) is filed, the employee pays taxes on that $48,000 today—about $16,000 in taxes. If a 83(b) is not filed, the employee pays taxes every time they vest, at the price of the stock when it vests. So while a share might be $1 today, it may be $5 in a year and $10 in two years. The employee is paying taxes as they vest, so the higher the price, the more they pay in taxes.

Additionally, when an employee leaves the company, their unvested options are automatically canceled, but if a company grants stock, it needs to buy the stock back from the employee. This isn’t difficult, but requires an extra bit of paperwork and administrative oversight that a startup wouldn’t otherwise have to handle.

The simple heuristic to decide which is best for an employee is to consider how expensive the stock will be to buy: when the price per share multiplied by the number of shares is more than $5,000–$10,000, most companies switch to options. This typically happens after you fundraise for the first time.

A note about options

Although options are typically easier to administer than stock, there are two areas in which founders often make suboptimal choices for their employees: (1) choosing the type of option that will lead to the best tax result for an employee and, relatedly, (2) whether to allow an employee to exercise unvested options.

Both of these rely on understanding how stock options are typically taxed. When an employee exercises an option (with an exception covered below), they are taxed at the difference between the current stock price of the company and the price they paid for their stock.

For example, if an employee exercises 1,000 options for $1 each (totaling $1,000) and the current stock price is $10 (making the stock worth $10,000), the employee will be taxed on $9,000 at their ordinary income tax rate.

Additionally, when the company is sold or goes public and the employee sells their stock, the employee will again be taxed on the investment gains from owning this stock. Following the example above, if the stock price increases to $100 and the employee sells, then the employee will owe taxes on the difference between their entry point ($10) and exit ($100). If the employee has held onto their stock for greater than one year, they will be taxed at the applicable long-term capital gains rate, otherwise they’ll be taxed at their ordinary income tax rate.

What’s the difference between ISOs and NSOs?

When granting an option, a company must decide whether to grant an “incentive stock option” (ISO) or “non-qualified stock option” (NSO). NSOs are traditional stock options and are taxed as described above.

A benefit of ISOs and NSOs is that they both qualify for long-term capital gains if the employee has held stock for one year and it has been two years from the time they received their option grant. ISOs have a second benefit. They are not taxable upon exercise whereas NSOs, by contrast, are taxed at the ordinary income tax rate upon exercise on the difference between the exercise price and the fair market value (FMV) of the underlying shares.

Because the benefit is so substantial, the IRS imposes a limit on the number of ISOs an employee may receive: this is equal to $100,000 worth of options that are exercisable in a single year. If this rule is violated, then the excess amount of ISOs are automatically treated as NSOs for tax purposes.

Founders often make this mistake with early executives by granting them options with a vesting schedule that naturally violates the $100,000 rule. For example, if a founder wanted to give an early hire $300,000 of stock options that vest over four years, they might think that since the grant vests over four years, that only $75,000 is exercisable and therefore under the $100,000 rule. That might be true, but is often not. Consider the following:

January 1: Executive is granted 300,000 options with a $1 strike price with a four-year vesting schedule and a one-year cliff.

January 1, the following year: The executive’s first 25% of her equity—or 75,000 options—vest and is exercisable (totaling $75,000).

On the first day of every month after: 6,250 options vest and become exercisable (totaling $6,250 each month).

May 1, of that year: 100,000 options will have vested and become exercisable for the tax year. This means that any additional options vested in the tax year would automatically be classified as NSOs instead of ISOs.

Timing is everything here because the IRS works off tax years—and employees with large grants can quickly get in trouble even with the most well-intentioned founders. This problem compounds with the activation of “early exercising.”

What is early exercising?

Traditionally, startup employees can only exercise vested options. However, an increasing number of startups allow employees to exercise unvested options—commonly known as “early exercising.”

At first blush, early exercising can seem like a win for employees: the earlier employees exercise, the sooner their stock will be subject to capital gains treatment at an exit event—and the lower the difference between the stock price and strike price, the lower the tax liability.

If an employee exercises NSOs when the stock price is equal to the strike price, they will not pay taxes at all, giving them the same benefit as an ISO—if an employee exercises quickly.

The problem with this strategy is that it forces employees to risk a lot of cash very early on in their tenure at a company to accrue a benefit—often before they have any information to make a decision on the likelihood that the company will succeed. In addition, because the entire grant can be exercisable the day it is granted, any grant that is greater than $100,000 (even if it vests over four years) will automatically break the ISO rule and the excess will be treated like an NSO.

Early exercising is favorable to bullish employees who have sufficient funds to exercise their options comfortably; it is unfavorable to employees with lower risk tolerance or liquid wealth. If employees are bullish on their company, then they likely don’t need the benefit of exercising early to stay motivated to work hard at the company. They already believe in the company’s growth prospects.

The recommended solution is to tailor early exercising on a per-employee basis to optimize tax consequences. A recent college graduate with loans won’t be able to exercise his $100,000 grant immediately and might benefit from a typical vesting and exercise schedule over four years. A senior executive with excess cash might be completely bought in and want to optimize her taxes by exercising all of her options ASAP, or she may decide that despite having sufficient cash, she isn’t quite ready to commit the cash to exercise options and would rather maintain the benefits of an ISO.

Final thoughts on employee equity

Equity compensation can be very challenging for founders because of its legal and tax complexities, both of which need mastering to convey to employees. Founders must educate themselves and their employees, who will almost never understand the mechanics as well as a founder might, but who will still be utterly dependent on them in the case that the company is successful.

The goal of equity compensation as a system is to be fair and feel fair to everyone involved. Cash compensation is predictable: it’s a number that’s simple to understand and manage. Equity compensation is mysterious. Employees must estimate how much it’s really worth after accounting for taxes, which is a complicated and changing calculation. With equity, a founder’s single best act is to ensure that employees are not getting cheated out of the compensation that was promised to them. Do right by your employees and they’ll do right by you.

Drawing from thousands of companies we’ve helped with equity plans, here is our distilled set of recommendations for an early-stage startup, from incorporation through its Series A. These can and will vary as you scale, but this starting point will offer you all of the tools you need to make the right decision for the most important set of people to your business: your earliest employees.

Pre-funding

Grant stock to employees and ensure they complete their 83(b) elections within a tight, 30-day window .

Stick to traditional four-year vesting with a one-year cliff because expending the time and energy to get creative is not a mission critical task at this stage.

Post-funding

Grant options.

Stick to traditional four-year vesting with a one-year cliff to remain fair and limit questions during the recruiting process.

For employees with an option grant that is worth greater than $100,000:

- Ask employees whether they want to exercise early.

- If they accept, grant NSOs and make sure employees actually exercise.

- If they decline, grant ISOs and work with counsel to tailor the vesting or exercise schedule to ensure compliance with the $100,000 rule.

- Ask employees whether they want to exercise early.

For employees with an option grant that is worth less than $100,000:

- Ask employees whether they want to exercise early.

- If they accept, grant NSOs and make sure employees actually exercise.

- If they decline, grant ISOs.

- Ask employees whether they want to exercise early.

Most startups will find success following this formula, but you will see larger companies pushing the boundaries on types of equity packages they are providing to employees, such as offering a loan in connection with stock instead of options or implementing a one-year vesting schedule. Stay firm. Most of the innovation in this space starts at the late-stage or public-company level, because those companies have enough resources to justify the administrative overhead. As your company grows, you’ll be in a position to be more innovative and forward-looking on employee compensation.

Use this guide to help ground best practices early on, but also to frame the financial and administrative tradeoffs that you’ll have to make for your employees as you scale. If you need additional, hands-on support, try Pulley. You can schedule a time with one of our cap table experts if you want to learn more about how to manage your employee equity more effectively.

This guide is not intended to and does not constitute legal or tax advice, recommendations, mediation or counseling under any circumstance. This guide and your use thereof does not create an attorney-client relationship with Stripe or Pulley. The guide solely represents the thoughts of the author and is neither endorsed by nor does it necessarily reflect Stripe’s belief. Stripe does not warrant or guarantee the accurateness, completeness, adequacy or currency of the information in the guide. You should seek the advice of a competent attorney or accountant licensed to practice in your jurisdiction for advice on your particular problem.