Abstract

Killer cell inhibitory receptors and CD94-NKG2-A/B heterodimers are major histocompatibility complex class I–specific inhibitory receptors expressed by natural killer cells, T cell antigen receptor (TCR)-γ/δ cells, and a subset of TCR-α/β cells. We studied the functional interaction between TCR-γ/δ and CD94, this inhibitory receptor being expressed on the majority of γ/δ T cells. When engaged by human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen class I molecules, CD94 downmodulates activation of human TCR-γ/δ by phosphorylated ligands. CD94-mediated inhibition is more effective at low than at high doses of TCR ligand, which may focus T cell responses towards antigen-presenting cells presenting high amounts of antigen. CD94 engagement has major effects on TCR signaling cascade. It facilitates recruitment of SHP-1 phosphatase to TCR–CD3 complex and affects phosphorylation of Lck and ZAP-70 kinase, but not of CD3 ζ chain upon TCR triggering. These events may cause abortion of proximal TCR-mediated signaling and set a higher TCR activation threshold.

Activation of NK cells is modulated by inhibitory receptors that interact with MHC class I molecules. The MHC class I–binding receptors currently identified have been assigned to two distinct groups that belong to the Ig (killer inhibitory receptors; KIR) and C-type lectin superfamilies (CD94), which here are collectively referred to as inhibitory receptors (IR). The p58.1, p58.2, p70, and the p70/140 KIRs recognize different supertypic epitopes of HLA-C, HLA-B, and HLA-A isoforms (for reviews see references 1–4). The second type of IR includes heterodimers of CD94 covalently associated with NKG2-A or NKG2-B molecules (5, 6). Both CD94 and NKG2 molecules are type II membrane glycoproteins that belong to the superfamily of C-type lectins. These receptors have a broader specificity in that they recognize different HLA-A, -B, and -C alleles (for review see reference 2).

KIRs inhibit cell triggering through recruitment and activation of intracellular phosphatases (for reviews see references 7 and 8), via a mechanism similar to that regulating B cells (9). The natural substrates of these phosphatases are not known and it is believed that they inhibit proximal tyrosine kinase activation (7, 8).

Surface expression of KIRs is not limited to NK cells, since T cells with TCR-α/β or -γ/δ are also KIR+. Only a limited number of TCR-α/β cells express p58.1, p58.2, and p70 KIR (10–12), and preferential expression of KIRs has been reported on CD45RO+ CD29+ memory cells (13). Based on these findings, it was proposed that KIRs are expressed by T cells after chronic cell activation and after generation of long-lived memory cells (2). It has also recently been reported that p70 KIR may inhibit activation of TCR-α/β by bacterial superantigens (11, 14) and by melanoma antigen (15).

Little is known about the functional role of IR on TCR-γ/δ T cells. Phenotypic studies showed that ∼60% of circulating γ/δ T cells are CD94+ (16). In contrast, expression of the p58 and p70 KIRs on γ/δ T cells is rare (12, 14, 17, 18). This study shows that CD94 finely downmodulates TCR-γ/δ activation induced by phosphorylated metabolites (19–21), as γ/δ T cell response is severely impaired in the presence of low, but not high, doses of ligand. This regulation correlates with increased recruitment of SHP-1 to CD94 and to the TCR–CD3 complex, with reduced Lck–TCR–CD3 complex association, and with ZAP-70 kinase hypophosphorylation.

Materials and Methods

T Cell Clones, Lines, and Phosphorylated Ligands.

T cell lines and clones were established and maintained as previously described (22). Isopentenylpyrophosphate (IPP) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (Buchs, Switzerland). Daudi cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD), and β2-microglobulin gene–transfected Daudi cells (Daudi-β2) were provided by Dr. J. Parnes (Stanford University, Stanford, CA; reference 23).

Immunofluorescence Analysis.

The following mAbs were used: B1 (IgG1) anti-pan TCR-γ/δ; B3 (IgG1) anti-Vγ9; 4A11 (IgG1) anti-Vγ4; 4G6 (IgG1) anti-Vδ2 (all characterized in our laboratory); δTCS1 (IgG1) anti-Vδ1-Jδ1/2 (Endogen, Boston, MA); P11.5B (IgG1) anti-Vδ3 (provided by Dr. M. Bonneville, INSERM Unité 211, Nantes, France); Q66 (IgM) anti-p140 (provided by Dr. L. Moretta, Laboratorio di Immunopatologia, Genova, Italy); GL183 (IgG1) anti-p58.2; HP3B1 (IgG2a) anti-CD94 (Immunotech, Marseilles, France); 5.133 (IgG1) anti-p140 and p70 (24); and HP3E4 (IgM) anti-p58.1 (provided by Dr. M. López-Botet, Hospital de la Princesa, Madrid, Spain). Three-color immunofluorescence analysis was performed using anti-TCR mAbs together with two anti-IR mAbs, when the isotype of the antibodies could be combined. First antibodies were revealed with mouse Ig isotype-specific FITC-, PE-, or biotin-labeled goat antisera (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) and streptavidin-3 color (Caltag, San Francisco, CA). A FACScan® flow cytometer with the Lysis II program was used for acquisition and analysis of data.

Cytokine Release Assays.

T cells (5 × 104/well) were stimulated by phosphorylated ligands in duplicate cultures in flat-bottomed 96-well plates in the presence of different types of APC (5 × 104/well). After 18 h of incubation, 100 μl of supernatant was removed and used to test the content of TNF-α by ELISA using commercial kits (Endotell, Bottmingen, Switzerland).

Killing Assays.

Cytotoxic assays were performed as previously described (25).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analyses.

The following mAbs were used for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting analysis: anti-CD3 ζ chain; anti-Lck and anti–SHP-1 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); anti–ZAP-70 and antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY); and H146-968 hamster mAbs which recognize human CD3 ζ chain (a gift of Dr. R. Kubo, Cytel Corp., San Diego, CA). Immunoprecipitation was performed using γ/δ T cells (5 × 106/ml) incubated with Daudi cells (8 × 106/ml) in the presence of IPP at 37°C for 30 min. To better detect the inhibitory effects of CD94 on γ/δ TCR, a suboptimal dose of IPP (10 μM) was used. Cells were washed twice in cold PBS at 4°C and then maintained for 40 min at 4°C in lysis buffer (1% digitonin, or 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, containing 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin). After centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min, supernatants were precleared with protein G–Sepharose beads (Pharmacia Biotech Europe, Dubendorf, Germany), and then with mouse Ig coupled to protein G–Sepharose, and then supernatants were incubated with indicated mAb–protein G–Sepharose at 4°C for 3 h. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times with 1 ml of 0.3% digitonin or NP-40 buffer and solubilized in Laemmli's sample buffer. Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (25). The presence of NKG2A was confirmed by PCR amplification and by detection of an ∼44-kD band with an anti-NKG2A antiserum in anti-CD94 immunoprecipitates (data not shown).

Results and Discussion

The Majority of Human TCR-γ/δ Cells Express at least One IR.

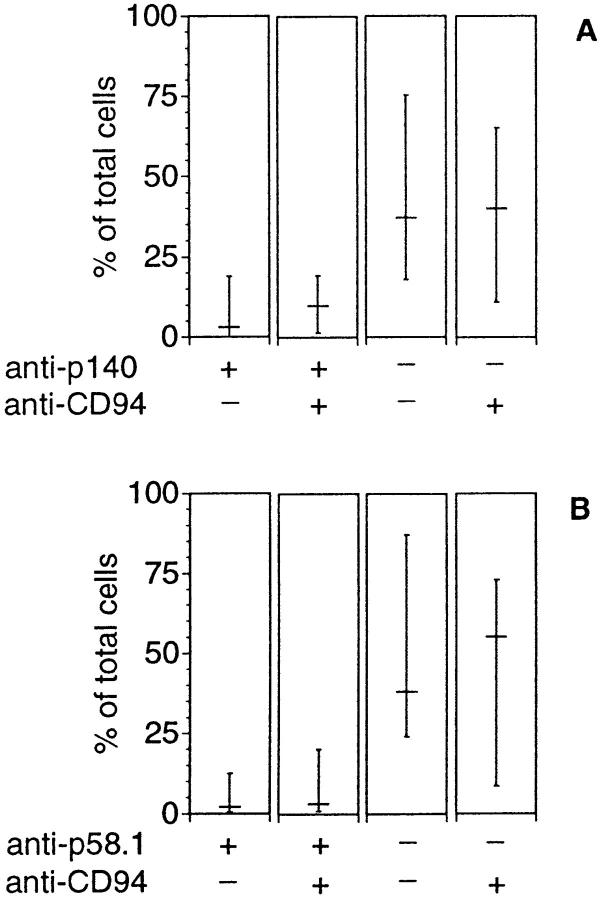

Using five different IR-specific mAbs, analysis of IR expression was performed on a panel of γ/δ T cell clones isolated from different donors and tissues. As shown in Fig. 1, most of the γ/δ clones derived from peripheral blood were positive for at least one mAb, thus demonstrating that, in contrast to what has been reported for αβ T cells (1–3, 16), IR are often expressed on the surface of γ/δ T cells. CD94 was the most frequently expressed IR, with 27 γ/δ clones positive out of the 40 tested. A smaller number of clones (15 out of 40) were p58.1, p58.2, p70, or p140 KIRs positive. Since all clones were activated under the same conditions and CD94− clones maintained a stable phenotype, it is unlikely that CD94 expression was induced during culture. Phenotypic comparison of clones bearing different types of Vγ/Vδ pairs revealed the tendency for Vγ9 (TCRVG2S1)/Vδ2 (TCRDV102S1) cells to be CD94+ more frequently than cells using other Vγ and Vδ chains, without reaching a statistically significant difference. The six CD4+ γ/δ clones tested were negative for all the anti-KIR mAbs (data not shown). They might represent a distinct population of γ/δ T cells with different TCR regulatory mechanisms. The same analysis performed on seven γ/δ clones derived from the thymus revealed only two positive clones. Conversely, all 12 γ/δ clones from the intestine were CD94+, and 6 of them coexpressed KIRs. Although we analyzed a limited number of clones, these results suggest that the expression of IR varies in different organs.

Figure 1.

Distribution of inhibitory receptors on γ/δ clones derived from PBMC, thymus, and gut. Immunofluorescence analyses were performed on 40 clones from PBMC, 7 from thymus, and 12 from intestine using anti-CD94, and anti-p58.1, p58.2, p70, and p140 KIR mAbs (see Materials and Methods). The area of each pie is proportional to the number of clones reactive with CD94 or KIR-specific antibodies. Clones reactive with at least one KIR Ab were grouped and indicated as KIR+.

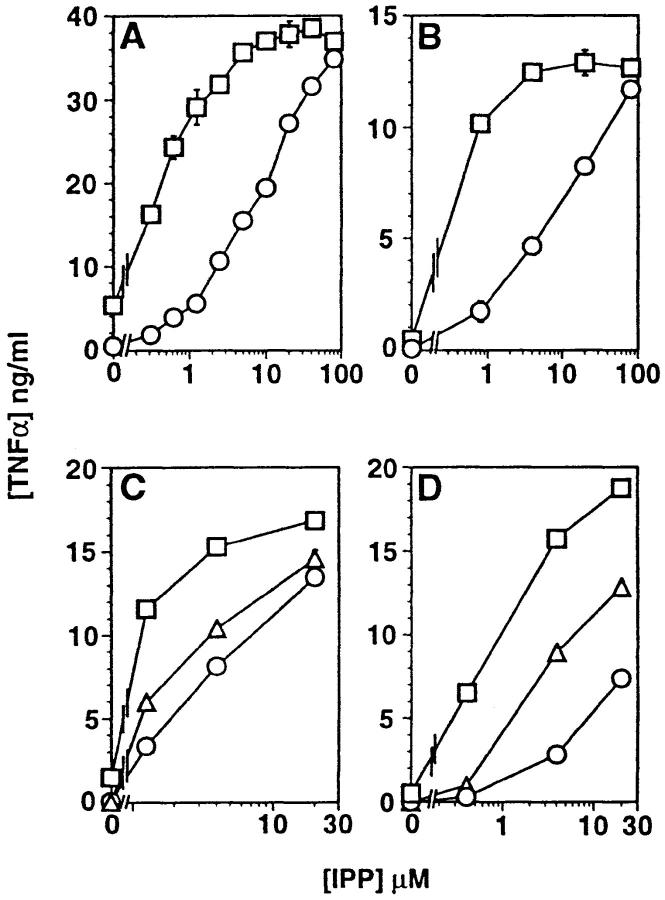

Coexpression of p140 and CD94, or p58.1 and CD94, was studied on total γ/δ T cells freshly isolated from nine donors (Fig. 2) or on subpopulations bearing different Vδ chains (data not shown). These analyses showed that CD94 is the most frequently expressed IR and that only a minority of γ/δ T cells express p140 and p58.1 KIRs, thereby confirming the results obtained with γ/δ clones. The expression of KIRs seemed to be biased because in some donors all the p140+ γ/δ T cells were CD94+, while in others p140+ γ/δ T cells were all CD94−. These findings could result from an oligoclonal expansion, as described for KIRs+ αβ T cells (13).

Figure 2.

Surface expression of IR molecules on freshly isolated γ/δ T cells. PBMCs from nine donors were stained with anti–pan-γ/δ mAbs together with two anti-IR mAbs, and three-color analyses were performed. The figure presents the percentage of γ/δ T cells reactive with Q66 (anti-p140) and HP3B1 (anti-CD94, A) or with HP3E4 (anti-p58.1) and HP3B1 (anti-CD94, B). Bars indicate medians and ranges of percentage of total γ/δ T cells.

Taken together, our phenotypic analysis indicates that expression of CD94 and KIRs by γ/δ T cells is not random, and it suggests that the microenvironment in which T cells are activated influences expression of IR.

CD94 Modulates TCR-γ/δ Activation.

As most of Vγ9/ Vδ2 cells express at least the CD94 molecule, we investigated the inhibitory capacity of this IR on TCR-γ/δ activation. Daudi Burkitt's lymphoma cell line, which does not express the β2-microglobulin gene and is therefore HLA class I−, is killed by γ/δ T cells bearing the Vγ9/Vδ2 TCR (26). We first studied whether killing of Daudi cells by CD94+ Vγ9/Vδ2 cells could be inhibited by CD94 engagement with HLA class I molecules. When Vγ9/Vδ2 cells were tested against β2-microglobulin gene–transfected Daudi cells (Daudi-β2; reference 23), which express HLA class I molecules on the surface, killing was reduced but could be partially restored by addition of anti-CD94 mAbs (data not shown). Thus, like KIRs (11, 12, 14, 17, 18), CD94 also inhibits TCR activation.

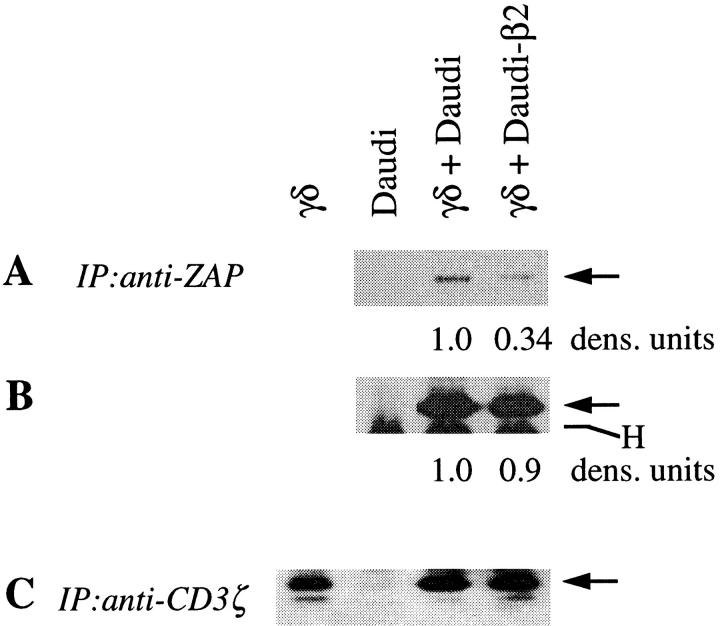

Human γ/δ T cells also react to a variety of nonpeptidic ligands, some of which are phosphorylated metabolites (19–21). We studied whether TCR-γ/δ activation by IPP, a strong agonist ligand (20, 21), could be inhibited by CD94. γ/δ clones were stimulated with different doses of IPP in the presence of Daudi or Daudi-β2 cells as APCs and TNF-α release was measured. The results confirmed that HLA class I+ APCs greatly reduce TCR-γ/δ–mediated cell activation (Fig. 3, A and B). TNF-α release was partially restored by addition of anti-CD94 mAbs, but not by isotype-matched irrelevant mAb (Fig. 3, C and D), thus further supporting the involvement of CD94. More importantly, CD94 engagement shifted the dose–response curve towards higher amounts of ligand. In the presence of Daudi-β2 APCs, 5–20 times higher doses of IPP were required than in the presence of Daudi APCs for an equivalent TNF-α release. This effect was consistently observed with four additional γ/δ clones (data not shown). These findings suggest that CD94 might serve the function of setting a higher cell activation threshold, as shown for other lymphocyte surface molecules (27).

Figure 3.

TNF-α release is highly influenced by HLA class I+ APCs when TCR-γ/δ is stimulated with low doses, but not high doses, of IPP. Two CD94+ clones, G2B2 (A and C) and D1C55 (B and D) were stimulated with increasing amounts of IPP in the presence of normal (□) or Daudi-β2 cells (○). Anti-CD94 (▵), but not an isotype-matched irrelevant mAb (○), partially restores TNF-α release in the presence of Daudi-β2 cells (C and D). Similar results were obtained in 14 independent experiments using these two clones and four other CD94+ γ/δ clones, derived from different donors. The amount of TNF-α released by a given clone in any given experiment was different and correlated with its activation state. Daudi cells do not release detectable TNF-α when incubated with IPP (not shown). Bars indicate SD.

Engagement of CD94 by HLA Class I Molecules Increases Recruitment of SHP-1 Phosphatase to CD94 and to the TCR– CD3 Complex and Causes Tyrosine Hypophosphorylation.

The inhibitory activities of KIRs have been ascribed to membrane recruitment of phosphatases and subsequent dephosphorylation of Lck, ZAP-70, and phospholipase C-γ (28). We tested whether SHP-1 phosphatase, which has been coprecipitated with the NKG2-A/NKR-P1C chimeric receptor (29), associates with CD94 expressed by γ/δ T cells. Indeed, SHP-1 was associated with CD94 in γ/δ T cells stimulated with IPP and the amount of coprecipitated SHP-1 was increased in the presence of Daudi-β2 APCs (Fig. 4 A).

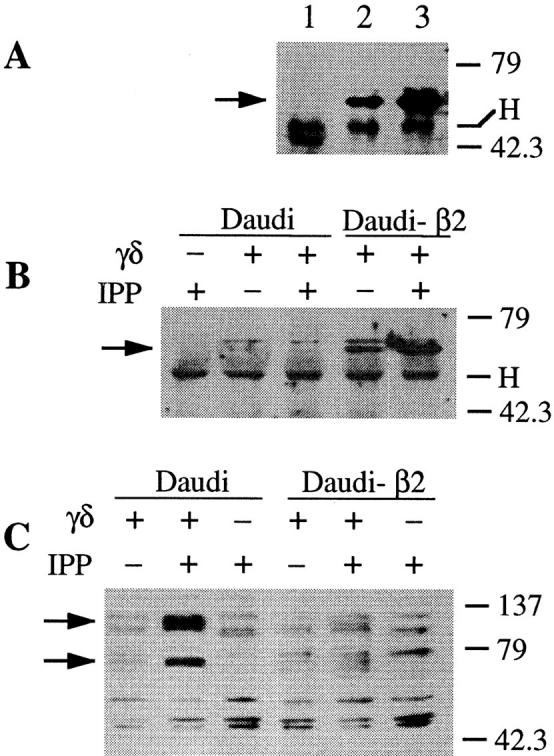

Figure 4.

TCR-γ/δ stimulation with IPP in the presence of HLA class I+ APC recruits increased amounts of SHP-1 phosphatase to CD94 and to TCR–CD3 complex and causes tyrosine hypophosphorylation. (A) Western blot performed with anti–SHP-1 Abs after immunoprecipitations carried out with anti-CD94 (lanes 2 and 3) or an isotype-matched irrelevant mAb (lane 1) from γ/δ T cells stimulated with IPP in the presence of Daudi (lanes 1 and 2) or Daudi-β2 APCs (lane 3). (B) Anti–SHP-1 Western blot after immunoprecipitation with anti-CD3 ζ chain mAbs. (C) Protein tyrosine phosphorylation of total cell lysates is visualized by immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 mAb. Cells were lysed with 1% digitonin (A and B) or with 1% NP-40 (C). Molecular mass markers are indicated on the right in kilodaltons. Arrows indicate SHP-1 in A and B, and two hypophosphorylated proteins migrating at ∼70 and 130 kD in C. H, Ig heavy chain of immunoprecipitating Abs.

SHP-1 phosphatase might affect TCR signaling by associating with and dephosphorylating components of the TCR–CD3 complex. In support of this hypothesis, SHP-1 was coprecipitated with the TCR–CD3 complex when γ/δ T cells were cultured in the presence of Daudi-β2, but not of Daudi APCs (Fig. 4 B). Thus, expression of MHC class I molecules on APCs is mandatory to detect this association, at least under the given experimental conditions. Moreover, increased amounts of SHP-1 were coprecipitated with the TCR–CD3 complex after stimulation with IPP (Fig. 4 B). TCR triggering might facilitate the association of SHP-1 with components of the TCR–CD3 complex or might initiate a cascade that facilitates the phosphorylation of CD94, the association of SHP-1 with CD94, and thus the recruitment of this phosphatase to the membrane (28). Once on the membrane, SHP-1 might be recruited to the TCR–CD3 complex more readily. This hypothesis implies that TCR and CD94 form a functional multimolecular complex where SHP-1 is brought into physical proximity with its substrates, as shown in another model (30).

The increased SHP-1–TCR association may be responsible for the alterations observed with some proteins involved in TCR signaling. In agreement with this possibility, we found that CD94 stimulation causes a reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of bands migrating at ∼70 and 130 kD (Fig. 4 C).

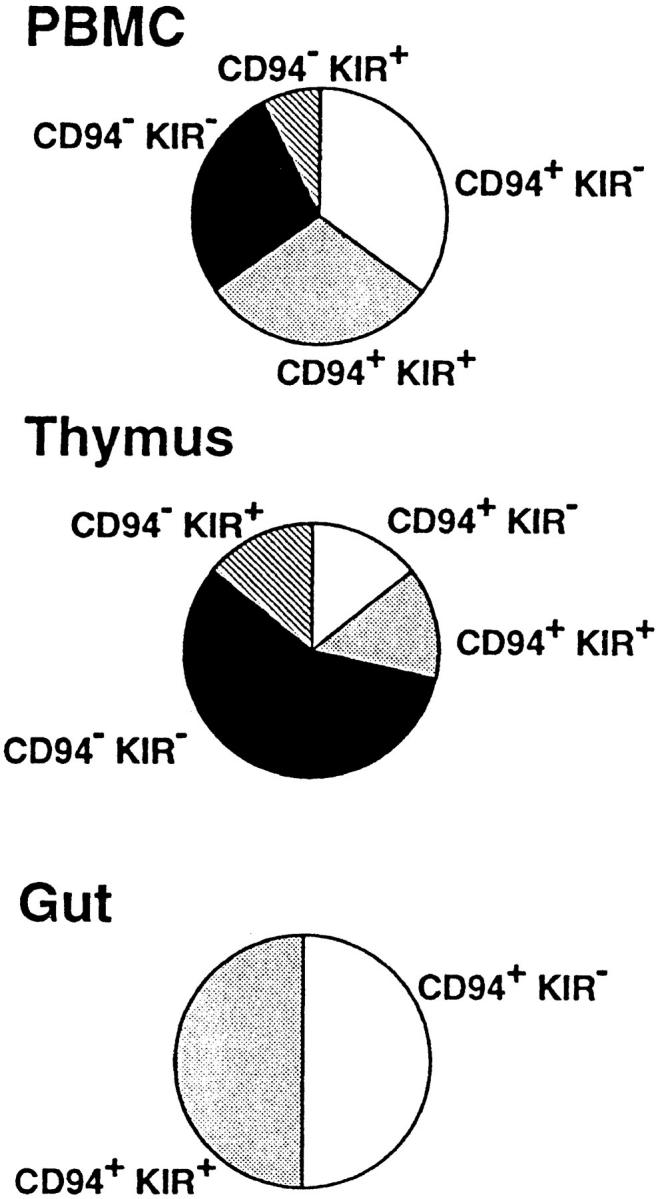

CD94 Engagement Affects ZAP-70 Phosphorylation, but not ZAP-70–CD3–TCR Complex Association.

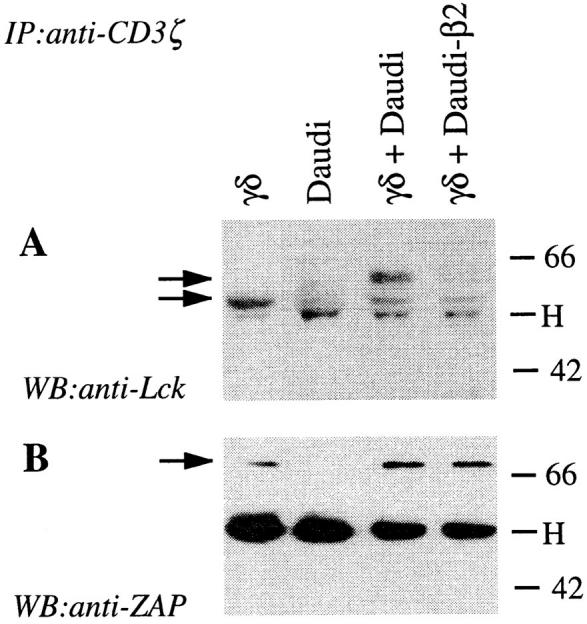

To better characterize which components of TCR signaling are affected by CD94 engagement with HLA class I molecules, γ/δ T cells were stimulated with IPP in the presence of Daudi or Daudi-β2 APCs, and then ZAP-70 and the CD3 ζ chain were individually precipitated and revealed using antiphosphotyrosine mAbs (Fig. 5). In additional experiments, the CD3–TCR complex was precipitated with anti-CD3 ζ chain mAb and the coprecipitated proteins revealed with specific antibodies (Fig. 6). These studies showed that when both the TCR and CD94 are engaged, ZAP-70 is hypophosphorylated (Fig. 5, A and B), although similar amounts are associated with the CD3–TCR complex (Fig. 6 B). In the same conditions, the lck form migrating at 60 kD is less abundant (Fig. 6 A), whereas the CD3 ζ chain is normally phosphorylated (Fig. 5 C). Thus, CD94 interaction with HLA class I molecules causes hypophosphorylation of ZAP-70, but not of the CD3 ζ chain. This finding is different from what has been observed with NK cell clones stimulated with anti-FcγRIII mAbs. In this case inhibition by anti-p70 KIR mAbs leads to CD3 ζ dephosphorylation (28). This discrepancy might be due to the used stimuli or to the type of receptors analyzed in the two studies (FcγR and p70 KIR versus TCR-γ/δ and CD94).

Figure 5.

Tyrosine phosphorylation is affected in CD94+ γ/δ T cells stimulated by IPP in the presence of HLA class I+ APCs. D1C55 cells were stimulated with IPP in the presence of normal or Daudi-β2 cells. As control, D1C55 or Daudi cells alone were incubated with IPP. Immunoprecipitations were carried out with anti–ZAP-70 (A and B), or anti-CD3 ζ chain mAbs (C). Cells were lysed with 1% NP-40 and precipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with HRP-conjugated antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 mAbs. The blot of anti–ZAP-70 immunoprecipitation was stripped and reblotted with anti–ZAP-70 mAbs (B). Arrows indicate ZAP-70 (A and B) and p21 CD3 ζ chain (C). H, Heavy chain of immunoprecipitating Abs. The amount of proteins in A and B were estimated by scanning densitometry analysis.

Figure 6.

Association of Lck but not of ZAP-70 with CD3 ζ chain is diminished by engagement of CD94. γ/δ T cells were stimulated as described in Fig. 5, lysed in 1% digitonin, and immunoprecipitated with anti-CD3 ζ chain mAbs. Precipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Lck mAb (A). Arrows indicate the position of p56 and p60 Lck. The blot was then stripped and reblotted with anti–ZAP-70 mAbs (B). The arrow indicates ZAP-70. Molecular mass markers are shown at the right side of the figure in kilodaltons. H, Heavy chain of immunoprecipitating Abs.

In conclusion, in γ/δ T cells stimulated with nonpeptidic ligands, CD94 engagement by HLA class I molecules leads to increased recruitment of SHP-1 to the TCR–CD3 complex, to reduced coprecipitation of Lck with the TCR–CD3 complex and to hypophosphorylation of ZAP-70. These findings may suggest that dephosphorylation of ZAP-70 is the key event blocking downstream TCR signaling.

Our data also show that the inhibitory mechanism of CD94 is different from that of antagonist ligands. In the latter case, the CD3 immunoglobulin receptor family tyrosine-based activatory motifs are partially tyrosine-phosphorylated and ZAP-70 does not associate with the CD3 ζ chain (31, 32).

An important issue concerns the implications of IR expression on the majority of γ/δ T cells, in particular the Vγ9/Vδ2 population, which is the most abundant circulating γ/δ population. Vγ9/Vδ2 cells recognize phosphorylated metabolites which are commonly found in eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells (for review see reference 33). Perhaps the function of IR is to prevent inappropriate and potentially dangerous γ/δ T cell activation by small quantities of these ubiquitous compounds.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Mori and T.J. Resink for critically reading the manuscript. We also thank M. Bonneville and P. Fish for helpful discussions, M. Bonneville, R. Kubo, M. López-Botet, and L. Moretta for providing mAbs, and J. Parnes for providing Daudi-β2 cells.

Footnotes

The Basel Institute for Immunology was founded and is supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. This work was supported by Swiss National Fund grant 31-045518.95 to G. De Libero.

References

- 1.Moretta A, Bottino C, Vitale M, Pende D, Biassoni R, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Receptors for HLA class-I molecules in human natural killer cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:619–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanier LL, Phillips JH. Inhibitory MHC class I receptors on NK cells and T cells. Immunol Today. 1996;17:86–91. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80585-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colonna M. Natural killer cell receptors specific for MHC class I molecules. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:101–107. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long EO, Burshtyn DN, Clark WP, Peruzzi M, Rajagopalan S, Rojo S, Wagtmann N, Winter CC. Killer cell inhibitory receptors: diversity, specificity and function. Immunol Rev. 1997;155:135–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazetic S, Chang C, Houchins JP, Lanier LL, Phillips JP. Human natural killer cell receptors involved in MHC class I recognition are disulfide-linked heterodimers of CD94 and NKG2 subunits. J Immunol. 1996;157:4741–4745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carretero M, Cantoni C, Bellon T, Bottino C, Biassoni R, Rodriguez A, Perez-Villar JJ, Moretta L, Moretta A, López-Botet M. The CD94 and NKG2-A C-type lectins covalently assemble to form a natural killer cell inhibitory receptor for HLA class I molecules. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:563–567. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vivier E, Daeron M. Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs. Immunol Today. 1997;18:286–291. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leibson PJ. Signal transduction during natural killer cell activation: inside the mind of a killer. Immunity. 1997;6:655–661. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satterthwaite A, Witte O. Genetic analysis of tyrosine kinase function in B cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:131–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falk CS, Steinle A, Schendel DJ. Expression of HLA-C molecules confers target cell resistance to some non– major histocompatibility complex–restricted T cells in a manner analogous to allospecific natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1005–1018. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Andrea A, Chang C, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. Regulation of T cell lymphokine production by killer cell inhibitory receptor recognition of self HLA class I alleles. J Exp Med. 1996;184:789–794. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mingari MC, Vitale C, Cambiaggi A, Schiavetti F, Melioli G, Ferrini S, Poggi A. Cytolytic T lymphocytes displaying natural killer (NK)-like activity: expression of NK-related functional receptors for HLA class I molecules (p58 and CD94) and inhibitory effect on the TCR-mediated target cell lysis or lymphokine production. Int Immunol. 1995;7:697–703. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.4.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mingari MC, Schiavetti F, Ponte M, Vitale C, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Demarest J, Pantaleo G, Fauci AS, Moretta L. Human CD8+T lymphocyte subsets that express HLA class I–specific inhibitory receptors represent oligoclonally or monoclonally expanded cell populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12433–12438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips JH, Gumperz JE, Parham P, Lanier LL. Superantigen-dependent, cell-mediated cytotoxicity inhibited by MHC class I receptors on T lymphocytes. Science (Wash DC) 1995;268:403–405. doi: 10.1126/science.7716542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda H, Lethé B, Lehmann F, Van Baren N, Baurain J-F, De Smet C, Chambost H, Vitale M, Moretta A, Boon T, Coulie PG. Characterization of an antigen that is recognized on a melanoma showing partial HLA loss by CTL expressing an NK inhibitory receptor. Immunity. 1997;6:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aramburu J, Balboa MA, Ramirez A, Silva A, Acevedo A, Sanchez-Madrid F, De Landazuri MO, López-Botet M. A novel functional cell surface dimer (Kp43) expressed by natural killer cells and T cell receptor-γ/δ+T lymphocytes. I. Inhibition of the IL-2 dependent proliferation by anti-Kp43 monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1990;144:3238–3247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrini S, Cambiaggi A, Meazza R, Sforzini S, Marciano S, Mingari MC, Moretta L. T cell clones expressing the natural killer cell–related p58 receptor molecule display heterogeneity in phenotypic properties and p58 function. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2294–2298. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakajima H, Tomiyama H, Takiguchi M. Inhibition of γ/δ T cell recognition by receptors for MHC class I molecules. J Immunol. 1995;155:4139–4142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Constant P, Davodeau F, Peyrat MA, Poquet Y, Puzo G, Bonneville M, Fournie JJ. Stimulation of human gamma delta T cells by nonpeptidic mycobacterial ligands. Science (Wash DC) 1994;264:267–270. doi: 10.1126/science.8146660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka Y, Morita CT, Tanaka Y, Nieves E, Brenner MB, Bloom BR. Natural and synthetic non-peptide antigens recognized by human gamma delta T cells. Nature (Lond) 1995;375:155–158. doi: 10.1038/375155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bürk MR, Mori L, De Libero G. Human Vγ9/ Vδ2 cells are stimulated in a cross-reactive fashion by a variety of phosphorylated metabolites. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2052–2058. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Libero G, Casorati G, Giachino C, Carbonara C, Migone N, Matzinger P, Lanzavecchia A. Selection by two powerful antigens may account for the presence of the major population of human peripheral γ/δ T cells. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1311–1322. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seong RH, Clayberger C, Krensky A, Parnes J. Rescue of Daudi cell HLA expression by transfection of the mouse β2-microglobulin gene. J Exp Med. 1988;167:288–299. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dohring C, Scheidegger D, Samaridis J, Cella M, Colonna M. A human killer inhibitory receptor specific for HLA-A1,2. J Immunol. 1996;156:3098–3101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bürk M, Carena I, Donda A, Mariani F, Mori L, De Libero G. Functional inactivation in the whole population of human Vγ9/Vδ2 T lymphocytes induced by a nonpeptidic antagonist. J Exp Med. 1997;185:91–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisch P, Malkovsky M, Braakman E, Sturm E, Bolhuis RL, Prieve A, Sosman JA, Lam VA, Sondel PM. γ/δ T cell clones and natural killer cell clones mediate distinct patterns of non–major histocompatibility complex– restricted cytolysis. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1567–1579. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.5.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tedder TF, Tuscano J, Sato S, Kehrl JH. CD22, a B lymphocyte–specific adhesion molecule that regulates antigen receptor signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:481–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Binstadt BA, Brumbaugh KM, Dick CJ, Scharenberg AM, Williams BL, Colonna M, Lanier LL, Kinet J-P, Abraham RT, Leibson PJ. Sequential involvement of lck and SHP-1 with MHC-recognizing receptors on NK cells inhibits FcR-initiated tyrosine kinase activation. Immunity. 1996;5:629–638. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Houchins JP, Lanier LL, Niemi EC, Phillips JH, Ryan JC. Natural killer cell cytolytic activity is inhibited by NKG2-A and activated by NKG2-C. J Immunol. 1997;158:3603–3609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bléry M, Delon J, Trautmann A, Cambiaggi A, Olcese L, Biassoni R, Moretta L, Chavrier P, Moretta A, Daeron M, Vivier E. Reconstituted killer cell inhibitory receptors for major histocompatibility complex class I molecules control mast cell activation induced via immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8989–8996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.8989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sloan-Lancaster J, Shaw AS, Rothbard JB, Allen PM. Partial T cell signaling: altered phospho-zeta and lack of Zap-70 recruitment in APL-induced T cell anergy. Cell. 1994;79:913–922. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madrenas J, Wange RL, Wang JL, Isakov N, Samelson LE, Germain RN. Zeta phosphorylation without ZAP-70 activation induced by TCR antagonists or partial agonists. Science (Wash DC) 1995;267:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.7824949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Libero G. Sentinel function of broadly reactive human γ/δ T cells. Immunol Today. 1997;18:22–26. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]