Abstract

Leukemia remains a major therapeutic challenge in clinical oncology. Despite significant advancements in treatment modalities, leukemia remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, as the current conventional therapies are accompanied by life-limiting adverse effects and a high risk of disease relapse. Histone deacetylase inhibitors have emerged as a promising group of antineoplastic agents due to their ability to modulate gene expression epigenetically. In this review, we explore these agents, their mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, safety and clinical efficacy, monotherapy and combination therapy strategies, and clinical challenges associated with histone deacetylase inhibitors in leukemia treatment, along with the latest evidence and ongoing studies in the field. In addition, we discuss future directions to optimize the therapeutic potential of these agents.

Keywords: Antineoplastic agents, Apoptosis, Epigenetics, HDAC inhibitor, Hematological malignancy, Histone deacetylases antagonist, Treatment resistance, Tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Leukemia arises from the uncontrolled proliferation of immature blood cells in the bone marrow and peripheral blood. Classified broadly into acute and chronic forms, leukemia is considered a multifactorial disease, involving a variety of genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors [1, 2]. Common symptoms of leukemia include fatigue, fever, easy bruising or bleeding, and recurrent infections, reflecting bone marrow failure and compromised immune function [3, 4]. Diagnosis typically involves a combination of clinical evaluation, peripheral blood smear, bone marrow aspiration, and genetic testing to subtype the disease and guide treatment decisions [5]. Despite therapeutic advances, leukemia remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality globally, with conventional therapies, facing limitations including toxicity and risk of relapse [6].

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors represent a class of pharmacological agents that modulate gene expression by targeting epigenetic mechanisms [7–9]. HDACs, enzymes responsible for removing acetyl groups from histone proteins, play a significant role in regulating chromatin structure and gene transcription [10, 11]. Dysregulation of HDAC activity is implicated in various diseases, including cancer, where aberrant gene expression contributes to tumorigenesis and progression [12, 13]. HDAC inhibitors exert their effects by inhibiting HDAC activity, leading to increased histone acetylation, chromatin relaxation, and transcriptional activation of genes involved in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and differentiation [8, 13]. Beyond histones, HDAC inhibitors can also target non-histone proteins [14]. Given their ability to modulate gene expression epigenetically, HDAC inhibitors have been proposed as promising therapeutic agents for a wide range of malignancies.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive clinical insight into the potential of HDAC inhibitors in the treatment of leukemia.

Main text

Mechanisms of action

In general, HDAC inhibitors exert their effects through multiple mechanisms, including:

Histone acetylation

HDAC inhibitors suppress the deacetylation of histone proteins, leading to chromatin relaxation and transcriptional activation of genes involved in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and differentiation [15].

Non-histone protein acetylation

HDAC inhibitors also acetylate non-histone proteins, such as transcription factors and signaling molecules, influencing various cellular processes critical for cancer pathogenesis [16].

Apoptosis induction

By upregulating pro-apoptotic genes, programmed activation of caspases, and downregulating anti-apoptotic genes, HDAC inhibitors promote apoptosis in malignant cells, leading to cell death [17–19].

Cell cycle arrest

HDAC inhibitors induce cell cycle arrest at different checkpoints, preventing uncontrolled proliferation of leukemic cells [20].

Anti-angiogenic effects

HDAC inhibitors have been shown to inhibit angiogenesis by targeting endothelial cell function and disrupting angiogenic signaling pathways, ultimately inhibiting the formation of new blood vessels in tumors [21]. HDAC inhibitors modulate the expression of genes involved in angiogenesis, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), and angiopoietins, through epigenetic mechanisms [22, 23]. By promoting histone acetylation and altering chromatin structure, HDAC inhibitors suppress the transcriptional activity of pro-angiogenic genes [24, 25]. Moreover, HDAC inhibitors have been shown to disrupt the tumor microenvironment by targeting stromal cells, immune cells, and extracellular matrix components, additionally impairing angiogenesis and tumor growth [26, 27].

Disruption of DNA repair mechanisms

HDAC inhibitors impair DNA repair mechanisms, enhancing the susceptibility of malignant cells to DNA damage-induced cell death [28, 29].

Autophagy induction

Previous studies have specified the autophagy-inducing role of HDAC inhibitors, generally through mTOR inhibition, NF-κB hyperacetylation, and p53 acetylation signaling pathways [30].

Classification

The classical family of HDACs are typically categorized into different classes. Each class shares a common ancestor and is characterized by structural and functional similarities [31]. The classical HDACs family is consisted of three classes [32, 33]:

Class I: HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, and HDAC8

Class II: HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC6, HDAC7, HDAC9, HDAC10

Class IV: HDAC11

Class III HDACs, also referred to as sirtuins, are structurally and mechanistically distinct. While class I and class II HDACs are zinc-dependent, class III HDACs require nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) as a cofactor for their deacetylase activity, which rises from the evolutionary divergence and distinct biochemical properties of sirtuins compared to classical HDACs [34, 35].

HDAC inhibitors can also be classified into structurally diverse classes, including hydroxamic acids (such as vorinostat and panobinostat), cyclic peptides (such as romidepsin), benzamides (such as entinostat), and short-chain fatty acids (such as valproic acid). These compounds differ in their chemical structures and HDAC isoform selectivity, leading to variations in their pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic effects.

Pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy

The pharmacokinetic properties of HDAC inhibitors, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination, influence their bioavailability and efficacy in vivo. HDAC inhibitors are administered via various routes, including oral and intravenous, with different absorption rates and tissue distribution profiles [36]. Oral formulations of HDAC inhibitors undergo absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, where they may be subject to first-pass metabolism in the liver before reaching systemic circulation. Intravenous administration bypasses the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in rapid and complete drug absorption into the bloodstream.

Several studies have evaluated the use of HDAC inhibitors, both as monotherapy and in combination with other agents, across various leukemia subtypes. While results have been variable, HDAC inhibitors have shown significant activity in subsets of patients, including those with relapsed or refractory disease who have failed standard therapies [37, 38]. Improved overall response rates (ORR), increased progression-free survival (PFS), and prolonged duration of response have been reported in certain trials, particularly in combination with chemotherapy or targeted agents [39, 40]. While HDAC inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy in specific leukemia subtypes, their clinical utility in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) remains under investigation [41]. Despite these encouraging findings, challenges such as drug resistance, heterogeneous patient populations, off-target effects, and optimal dosing schedules remain areas of active investigation [42, 43].

Safety

The safety profile of HDAC inhibitors in leukemia treatment is a subject of considerable interest and investigation. While HDAC inhibitors have shown promising therapeutic efficacy in preclinical and clinical studies, their clinical use could be associated with various adverse effects, including cardiac toxicity, gastrointestinal disturbances, fatigue, and hematologic toxicity [43–45]. Hematologic toxicity, in the forms of thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and anemia, is among the most commonly reported adverse events [46]. Gastrointestinal discomfort, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and loss of appetite, is also frequently observed and may require supportive care measures [36, 47, 48]. Cardiac toxicity, characterized by QT interval prolongation, T-wave flattening, ST segment depression, and arrhythmias, has been reported with specific HDAC inhibitors and underscores the importance of cardiac monitoring during therapy [43, 49]. In addition, some studies have suggested electrolyte abnormalities subsequent to administration of HDAC inhibitors as the cause of cardiac side effects [50]. Overall, further studies are required to determine the complete safety profile of HDAC inhibitors in leukemia treatment and ensure their tolerability and long-term efficacy in patients.

Clinical agents and candidates

Several agents have been proposed and studied through the last decades. Tables 1 and 2 present a comprehensive review of the preclinical and clinical studies of HDAC inhibitors. The most prominent HDAC inhibitors candidates for the treatment of leukemia are:

Table 1.

Preclinical studies of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in leukemia (non-leukemia reports also presented in the absence of sufficient studies)

| HDAC class | Author (year) | Agent | Combination therapy | Cell lines | Leukemia subtype | Findings and outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxamic acids | Gao et al. (2016) [131] | Vorinostat (SAHA) | Carfilzomib | MOLT-4 and HuT 78 | TCL | Vorinostat, in combination with carfilzomib, showed synergistically improved anticancer effects |

| Chao et al. (2015) [132] | Vorinostat (SAHA) | Vincristine | MOLT-4 and CCRF-CEM | T-ALL | Combined vorinostat and vincristine induce the pro-apoptotic pathways, resulting in significant antileukemic effects | |

| Young et al. (2017) [133] | Vorinostat (SAHA) | Decitabine | OCI-AML3 and HL-60 | AML, APL | The combination of vorinostat and decitabine benefits from synergistically improved response and could act as a potential treatment for AML. In addition, AXL is a potential marker for decitabine-vorinostat treatment response | |

| Valdez et al. (2022) [134] | Panobinostat (LBH589) | Bisantrene, venetoclax, decitabine, and olaparib | OCI-AML3, MOLM-13, and MV4-11 | AML | The combination therapy resulted in synergistic cytotoxicity in cells, damage response, and upregulation of apoptosis pathways | |

| Jia et al. (2019) [135] | Panobinostat (LBH589) | Sodium butyrate (HDAC inhibitor) | K-562 | CML | The combination shows antileukemic effects through activation of the ERS-mediated apoptotic pathway and reduction of drug-resistance related proteins’ expression | |

| Moreno et al. (2022) [136] | Panobinostat (LBH589) | Mercaptopurine and methotrexate | RS4;11 | ALL | No synergistic effect was observed through combination therapy of panobinostat with methotrexate and mercaptopurine. However, Panobinostat monotherapy demonstrated significant antineoplastic effects | |

| Vagapova et al. (2021) [137] | Belinostat, hydrazostat (Belinostat-PH) | Imatinib, cytarabine, vincristine, and venetoclax | MV4-11, THP-1, HL-60, U-937, and K-562 | AML, APL, CML | Hydrazostat improves the sensitivity of leukemic cells to imatinib, cytarabine, vincristine, and venetoclax | |

| Diamanti et al. (2007) [138] | Belinostat (PXD101) | Chemotherapy (VAD) | CCRF-CEM, MOLT-4, Jurkat, NALM6, Daudi, and Kasumi | ALL, AML | Inducing apoptosis, belinostat was effective in steroid-resistant samples, but no synergy was observed in combination therapy | |

| Valiuliene et al. (2015) [139] | Belinostat (PXD101) | Retinoic acid | NB4 and HL-60 | APL | Belinostat demonstrated antileukemic effects through its impact on chromatin remodeling and cell growth | |

| Pietschmann et al. (2012) [140] | Panobinostat (LBH589) | TKI (FLT3 inhibitors: quizartinib, midostaurin, cpd.102) | MV4-11 and MOLM-13 | AML | HDAC inhibitors and FLT3 inhibiting agents have significant synergistic antileukemic activity with strong induction of apoptosis even in low doses | |

| Cyclic peptides | Dai et al. (2008) [141] | Romidepsin (FK228) | Belinostat and bortezomib | JVM-3 and MEC-2 | CLL (P-BLL) | The combination of Romidepsin and belinostat with bortezomib synergistically induces cell death in CLL cells |

| Alves da Silva et al. (2022) [142] | Romidepsin (FK228) | 7C6 (MICA/B antibody) | NB4, C1498, and WEHI-3 | AML | Romidepsin synergizes the MICA/B inhibition properties of 7C6, suppressing the AML outgrowth through antibody-dependent phagocytosis | |

| Benzamides | He et al. (2020) [143] | Chidamide (CS055/HBI-8000) | Imatinib | KBM5 | CML | The combination of chidamide and omatinib reduces TKI resistance and could improve the clinical outcomes of BC-CML patients |

| Zhao et al. (2022) [144] | Chidamide (CS055/HBI-8000) | Apatinib | KG1α and Kasumi-1 | AML | Combination therapy of chidamide and apatinib synergistically affected cell viability and induced pro-apoptotic pathways | |

| Hu et al. (2024) [145] | Chidamide (CS055/HBI-8000) | – | HL-60, HEL, MOLM-13, MV4-11, and Kasumi-1 | AML | Affecting N6-methyladenosine-related GNAS-AS1, chidamide results in glycolysis suppression | |

| Gu et al. (2023) [146] | Chidamide (CS055/HBI-8000) | Cladribine | U937, THP-1, and MV4-11 | AML | Affecting the HDAC2/c-Myc/RCC1 pathway, coadministration of chidamide with cladribine synergistically targets cell growth, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis | |

| Yin et al. (2023) [147] | Chidamide (CS055/HBI-8000) | Imatinib and nilotinib | Ba/F3 P210 and Ba/F3 T315I | CML | Chidamide monotherapy can potentially overcome T315I mutation-related drug resistance through the modulation of apoptosis-autophagy pathways. Combining chidamide with TKI agents, such as Imatinib or nilotinib, increases its effectiveness | |

| Wang et al. (2018) [148] | Entinostat (SNDX-275, MS-275) | Cladribine | RPMI8226, U266, and MM1.R | MM | Coadministration of entinostat and cladribine induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, affecting the DNA damage response | |

| Zhou et al. (2013) [149] | Entinostat (SNDX-275, MS-275) | Vorinostat, trichostatin A, romidepsin | HL-60, MOLM-13, OCI-AML3, and OCI-AML2 | AML | Entinostat, along with other HDAC inhibitors, promotes apoptosis by restoring the silenced nuclear receptors Nur77 and Nor1 | |

| Golay et al. (2007) [150] | Givinostat (ITF2357) | – | HL-60, THP-1, U937, Kasumi, KG-1, TF-1, GFD8 | AML, APL | Potent anti-leukemic activity through suppressing IL-6 and VEGF production, resulting in increased apoptosis in vitro and increased survival in vivo | |

| El-Khoury et al. (2014) [151] | Mocetinostat (MGCD0103) (and Valproic acid) | Flavopiridol (CKDi), chloroquine, 3-MA | MCF-7, JVM-2, and JVM-3 | B-CLL | Mocetinostat induces apoptosis, along with autophagy suppression in all combination regimens | |

| Short-chain fatty acids | Rucker et al. (2016) [152] | Valproic acid | Chemotherapy (ICE, ATRA) | CMK, HEL, K-562, NB4, and HL-60 | AML, APL | Valproic acid has shown synergistic effects in the treatment of AML when combined with intensive chemotherapy regimens |

3-MA 3-Methyladenine, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, APL acute promyelocytic leukemia, ATRA all-trans retinoic acid, BC-CML blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia, B-CLL B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, B-PLL B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia, CDK cyclin-dependent kinase, CML chronic myelocytic leukemia, ERS endoplasmic reticulum stress, FLT3 FMS‐like tyrosine kinase 3, HDAC histone deacetylases, ICE idarubicin, cytarabine, etoposide, IL interleukin, MICA/B histocompatibility complex class I polypeptide-related sequence A and B, MM multiple myeloma, SAHA suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, T-ALL T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, TCL T cell lymphoma, TKI tyrosine kinase inhibitor, VAD vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

Table 2.

Clinical studies on efficacy/safety of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in the treatment of leukemia (non-leukemia reports also presented in the absence of sufficient studies)

| HDAC class | Author (year) | Country | Trial design | Candidate | Combination therapy | Leukemia subtype | Clinical outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxamic acids | Schafer et al. (2022) [153] | USA | Phase I trial | Vorinostat (SAHA) | Chemotherapy (decitabine and FLAG) | AML | With an ORR of 69% in relapsed and 38% in refractory AML, the combination of vorinostat with decitabine and FLAG-based therapies was well-tolerated and effective in this study |

| Alatrash et al. (2022) [154] | USA | Phase I/II trial | Vorinostat (SAHA) | Conditioning regimen (CloFluBu) | ALL, AML, MDS | Vorinostat did not show improvement in combination with CloFluBu for leukemia patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT | |

| Burke et al. (2020) [155] | USA | Phase I/II trial | Vorinostat (SAHA) | Chemotherapy (decitabine, dexamethasone, vincristine, mitoxantrone, PEG-asparaginase) | B-ALL | Decitabine and vorinostat combination led to unacceptable toxicities in B-ALL | |

| Garcia-Manero et al. (2024) [156] | USA | Phase III trial | Vorinostat (SAHA) | Chemotherapy (cytarabine) | AML | High-dose Cytarabine during the induction therapy will not improve the AML clinical outcomes, regardless of the combination with Vorinostat | |

| DeAngelo et al. (2019) [157] | USA | Phase I trial | Panobinostat (LBH589) | Chemotherapy (idarubicin, cytarabine) | AML | An ORR of 60.9% with 43.5% CR and 78.3% EFS was observed | |

| Goldberg et al. (2020) [158] | USA | Phase I trial | Panobinostat (LBH589) | Chemotherapy (unspecified) | AML, ALL, NHL | Panobinostat was tolerated in heavily pretreated pediatric subjects. Gastrointestinal effects were observed in this study. There were no cardiac findings. There were no responses | |

| Wieduwilt et al. (2019) [159] | USA | Phase I trial | Panobinostat (LBH589) | Chemotherapy (7 + 3) | AML | The combination of Panobinostat with the chemotherapy was well-tolerated, with a CR/CRi rate of 32% | |

| Perez et al. (2021) [160] | USA | Phase II trial | Panobinostat (LBH589) |

Chemotherapy (myeloablative/reduced intensity of busulfan, melphalan, and fludarabine) Tacrolimus/sirolimus for GVHD prophylaxis |

ALL, AML, MDS | Panobinostat combined with standard GVHD prophylaxis resulted in a low cumulative incidence of clinically significant acute GVHD, without major adverse events, making it a safe and feasible intervention | |

| Gimsing et al. (2008) [161] | Denmark | Phase I trial | Belinostat (PXD101) | Chemotherapy, radiation therapy (unspecified) | CLL, MM, NHL | Belinostat is well-tolerated in patients with hematological malignancies | |

| Shafer et al. (2023) [162] | USA | Phase I trial | Belinostat (PXD101) | Adavosertib | AML, MDS | Coadministration of belinostat and Adavosertib is safe and feasible, but no significant clinical improvement was observed among patients | |

| Holkova et al. (2021) [163] | USA | Phase I trial | Belinostat (PXD101) | Bortezomib | AML, MDS | Coadministration of belinostat and bortezomib is safe and feasible, but shows limited activity in leukemic patients | |

| Kirschbaum et al. (2014) [164] | USA | Phase II trial | Belinostat (PXD101) | – | AML | No CR was observed among the patients, and belinostat monotherapy minimally affects AML | |

| Garcia-Manero et al. (2024) [165] | Multicenter | Phase III trial | Pracinostat (SB939) | Azacitidine | AML | Lack of clinical response was observed, with no significant difference reflected by adding pracinostat to the treatment protocol | |

| Cyclic peptides | Holkova et al. (2017) [166] | USA | Phase I trial | Romidepsin (FK228) | Bortezomib | CLL/SLL, BCL, PTCL, CTCL | PR and stable disease was observed among 12.2% and 44.4% of patients, respectively. Grade III fatigue, N/V, and chills were the observed dose-limiting toxicities |

| Chiappella et al. (2023) [167] | Italy | Phase Ib/II | Romidepsin (FK228) | Chemotherapy (CHOEP), SCT | PTCL | No unexpected toxicities were recorded, with an ORR of 71% and CR of 62%. Romidepsin and CHOEP combination therapy did not improve the PFS of untreated patients; however, the primary endpoint of this study was not met | |

| Harrison et al. (2011) [168] | Australia | Phase I/II trial | Romidepsin (FK228) | Bortezomib and dexamethasone | MM | With a 72% OR, combination therapy of romidepsin with bortezomib/dexamethasone shows significant anticancer properties with manageable toxicity | |

| Niesvizky et al. (2011) [169] | USA | Phase II trial | Romidepsin (FK228) | Chemotherapy, radiation therapy (unspecified) | MM | Monotherapy of romidepsin is unlikely to result in a significant objective response in refractory MM | |

| Benzamides | Wang et al. (2020) [170] | China | Phase I/II trial | Chidamide (CS055/HBI-8000) | Chemotherapy (DCAG) | AML | The combination of chidamide and DCAG was well-tolerated and effective in relapsed/refractory AML |

| Wei et al. (2023) [171] | China | Phase II trial | Chidamide (CS055/HBI-8000) | Chemotherapy (CAG), DLI | AML, MDS | With a 45% CR, 5% PR, and median OS of 19 months, the combination of chidamide with CAG and DLI is superior for post-allo-HSCT AML/MDS patients | |

| Shi et al. (2017) [172] | China | Phase IIb trial | Chidamide (CS055/HBI-8000) |

Chemotherapy (CHOP-like regimens, platinum-containing regimens) |

TCL | Median PFS was 129 vs 152 for monotherapy against combination therapy. With a 51.18% ORR, chidamide has a suitable efficacy and safety profile, and could be potentially used for refractory and relapsed PTCL patients | |

| Carraway et al. (2021) [173] | USA | Phase I trial | Entinostat (SNDX-275, MS-275) | Chemotherapy (Clofarabine) | ALL, ABL | The combination of entinostat with clofarabine is tolerable and effective. The impact of this combination on relapsed/refractory patients seems to be inferior to the newly diagnosed | |

| Bewersdorf et al. (2024) [174] | USA | Phase Ib trial | Entinostat (SNDX-275, MS-275) | Immunotherapy (Pembrolizumab) | AML, MDS | Coadministration of entinostat and pembrolizumab was related to limited clinical efficacy despite significant toxicity | |

| Garcia-Manero et al. (2008) [175] | USA | Phase I trial | Mocetinostat (MGCD0103) | – | AML, MDS | Mocetinostat monotherapy was proven safe and effective | |

| Blum et al. (2009) [176] | USA | Phase II trial | Mocetinostat (MGCD0103) | Rituximab | CLL | Mocetinostat monotherapy and combination therapy were safe. Number of patients in each intervention group is way too small to draw any conclusion on effectiveness | |

| Short branched-chain fatty acids | Lübbert et al. (2020) [177] | Germany | Phase II trial | Valproic acid | Chemotherapy (Decitabine, ATRA) | AML | No significant superiority of OS was observed in patients receiving valproate |

| Becker et al. (2021) [178] | Germany | Phase II trial | Valproic acid | Chemotherapy (Decitabine, ATRA) | AML | Valproic acid did not affect the ORR in the study groups | |

| Tassara et al. (2014) [179] | Germany | Phase III trial | Valproic acid | Chemotherapy (Idarubicin, cytarabine, ATRA) | AML | RFS was improved in patients receiving valproic acid; however, no significant difference was observed in EFS and OS |

ABL Acute biphenotypic leukemia, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, ATRA all-trans retinoic acid, B-ALL B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, BCL B-cell lymphoma, CAG cytarabine, aclarubicin, GCSF, CHOEP cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, etoposide, CHOP cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone, CLL chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CloFluBu clofarabine, fludarabine, busulfan, CML chronic myelocytic leukemia, CR/CRi Complete response/incomplete count recovery rate, CR complete remission, CTCL cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, DCAG decitabine, cytarabine, aclarubicin, GCSF, DLI donor lymphocyte infusion, EFS event-free survival, FLAG fludarabine, cytarabine and GCSF, GCSF granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, GDP gemcitabine, dexamethasone and cisplatin, GVHD graft-versus-host disease, HCT hematopoietic cell transplantation, HDAC histone deacetylase, HSCT hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, ICE idarubicin, cytarabine, etoposide, MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, MM multiple myeloma, N/V nausea and vomiting, NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma, OR overall response, ORR overall response rate, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, PR patrial remission, PTCL peripheral T-cell lymphoma, RFS relapse-free survival, SAHA suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, SCT stem cell transplantation, SLL small lymphocytic lymphoma, TCL T cell lymphoma, VAD vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone

Vorinostat

Vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, SAHA) is a broad-spectrum HDAC inhibitor that targets class I, II, and IV HDAC enzymes [51, 52]. By inhibiting these enzymes, vorinostat increases the acetylation of histone proteins, leading to the transcriptional activation of genes that induce cell cycle arrest, promote apoptosis, and inhibit tumor angiogenesis [53, 54]. This modulation of gene expression disrupts cancer cell proliferation and survival. Initially approved for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), its potential has also been explored in AML and other hematological malignancies [15, 55, 56]. Studies have demonstrated its ability to synergize with other therapeutic agents, enhancing the cytotoxic effects against leukemic cells by disrupting mitochondrial function and inducing oxidative stress, which leads to apoptosis in leukemic cells [57].

Romidepsin

Romidepsin (FK228) is a selective inhibitor of class I HDACs, particularly HDAC1 and HDAC2 [58, 59]. Its anti-tumor activity is attributed to its strong induction of G2/M cell cycle arrest and activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway [60]. Romidepsin modifies the expression of key apoptotic regulators, enhancing the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins and suppressing anti-apoptotic proteins [61]. Primarily approved for CTCL and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), romidepsin has been evaluated in clinical trials involving patients with various forms of leukemia [62]. Recent studies indicate the potential of romidepsin in downregulating DNA methyltransferases, leading to the demethylation of tumor suppressor genes and reactivation of their expression, thereby providing a dual epigenetic therapy approach when combined with DNA methylation inhibitors [63, 64].

Belinostat

Like vorinostat, belinostat (PXD101) is a pan-HDAC inhibitor that affects class I, II, and IV enzymes [65]. Its anticancer effects are mediated through the induction of apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and the reduction of angiogenesis [66–68]. Belinostat also affects the acetylation of non-histone proteins critical in cell cycle regulation and apoptosis [68, 69]. While belinostat is approved for PTCL, its role in treating leukemia subtypes is under investigation. Preclinical models show that Belinostat effectively induces death in leukemic cells, particularly when combined with other chemotherapeutic or targeted agents, enhancing its antileukemic activities [68].

Panobinostat

Panobinostat (LBH589) inhibits class I, II, and IV HDAC enzymes, which results in a more robust increase in histone acetylation compared to other HDAC inhibitors [15, 70]. This extensive hyper-acetylation disrupts many cellular processes in cancer cells, including gene expression, cell cycle progression, and survival pathways. Initially approved for multiple myeloma (MM) in 2015, panobinostat has demonstrated significant potential in preclinical studies for the treatment of ALL [71–73]. It has been shown to induce apoptosis and enhance the efficacy of other therapeutic agents like bortezomib through synergistic mechanisms in leukemic cells [74]. Furthermore, panobinostat has been involved in clinical trials aimed at evaluating its effectiveness in overcoming drug resistance and preventing disease relapse in leukemia patients [75].

Chidamide

Chidamide, also known as CS055/HBI-8000, is a novel benzamide class HDACi that has shown promising activity in preclinical models and clinical trials for the treatment of leukemia [76, 77]. Chidamide selectively inhibits class I HDACs (HDAC1, 2, 3, and 10), leading to increased histone acetylation and modulation of gene expression [78, 79]. Chidamide has demonstrated antileukemic activity in preclinical and clinical studies, particularly in patients with relapsed or refractory disease [80, 81]. Combination therapy strategies, administrating chidamide along with chemotherapy agents or targeted therapies, are being explored to enhance therapeutic efficacy and overcome drug resistance.

Entinostat

Entinostat, (MS-275, SNDX-275), is a synthetic benzamide derivative that selectively inhibits class I HDAC [82]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated the ability of entinostat in the induction of cell cycle arrest and expression of pro-apoptotic proteins in leukemic cells [83]. Recent clinical trials evaluating entinostat as monotherapy or in combination with other agents have shown promising results in leukemia patients, including those with AML and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) [84, 85]. Combining entinostat with hypomethylating agents such as azacitidine has been extensively studied as a potential treatment regimen for leukemia patients [85, 86].

Mocetinostat

Mocetinostat (MGCD0103) is a highly selective inhibitor of class I and IV HDAC isoforms that has demonstrated preclinical activity against leukemia cells [87, 88]. Mocetinostat also establishes antileukemic effects through the induction of apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and modulation of gene expression. Clinical studies of mocetinostat in the treatment of leukemia are still ongoing, and the results are indefinite to date.

Givinostat

Givinostat (ITF2357) is a hydroxamic acid derivative inhibiting class I and IIb HDAC isoforms [89]. Givinostat has demonstrated preclinical activity in leukemia models, including the induction of apoptosis and differentiation of leukemic cells [90, 91]. Clinical studies investigating givinostat in leukemia patients, particularly those with AML and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), are ongoing, evaluating the patients’ hematologic responses and improvements in disease-related symptoms.

Other candidates

Several other candidates are being studied preclinically, including fimepinostat (CUDC-907), ivaltinostat (CG-200745), and CUDC-101, which are chiefly studied for solid tumors, but also considered for relapsed/refractory hematologic malignancies [42, 92–94].

Repurposed agents

Due to the heterogenic spectrum of HDAC classes, the development of novel HDAC-targeting agents has been challenging, which has led to frequent endeavors to repurpose the currently available drugs [95, 96]. Trichostatin A is an antibiotic antifungal agent with specific class I and II HDAC inhibitory properties, which has also demonstrated significant anti-leukemic effects in preclinical studies [97–99]. Apicidin is another fungal metabolite with HDAC inhibitory properties, which has been proven to induce pro-apoptotic activities in hematological malignancies [100, 101].

In addition, some distant agents, such as valproic acid—which is primarily used as an antiepileptic medication—have also shown HDAC inhibitory activities [102, 103], which, although might not be a primary choice of cancer treatment, have demonstrated strong evidence for positive antileukemic effects in combination with novel and conventional cancer therapies [104].

Combination therapies

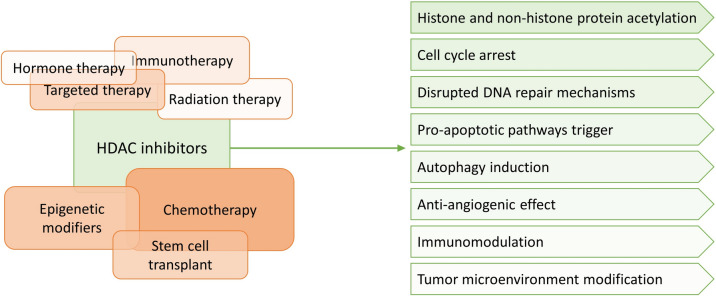

Several studies have proposed therapeutic regimens of HDAC inhibitors combined with other treatment modalities in order to overcome resistance, minimize off-target effects, and increase the clinical efficacy for the treatment of leukemia subtypes [105]. As displayed in Fig. 1, these combination regimens can synergistically enhance antitumor effects and improve patient outcomes. Several combination protocols are being studied, the main of which being:

Fig. 1.

HDAC inhibitors exhibit antileukemic effects, either as monotherapy or in combination with other treatment modalities

Combination with chemotherapeutic agents

Combining HDAC inhibitors with conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy agents is a rational approach to enhance tumor cell destruction and overcome chemotherapy resistance [106]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated synergistic interactions between HDAC inhibitors and agents, such as cytarabine, doxorubicin, and vincristine in leukemia models, leading to activation of pro-apoptosis pathway and cell cycle arrest in leukemic cells [107]. Clinical trials evaluating the combination of HDAC inhibitors with chemotherapy regimens in leukemia patients have shown promising results, including improved response rates and survival outcomes, mostly with acceptable toxicity levels (Table 2).

Combination with immunotherapy

HDAC inhibitors can modulate the tumor microenvironment, enhance antigen presentation, and promote antitumor immune responses [108–110]. Previous studies suggested a significant synergistic effect for the coadministration of HDAC inhibitors and immunomodulating agents in solid tumors, with potentially high levels of toxicity [111]. However, the studies on hematological malignancies are still indefinite. Considering the rapidly evolving landscape of cancer immunotherapy, further studies are required to determine the effectiveness and safety of these combinations, particularly in treatment regimens involving immune checkpoint inhibitors and tumor microenvironment components, such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [112, 113].

Combination with targeted therapies

Combining HDAC inhibitors with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeting aberrant signaling pathways such as FLT3, BCR–ABL, or JAK–STAT has shown promise in preclinical models of leukemia, leading to enhanced apoptosis and inhibition of leukemic cell proliferation [114–116]. Gilteritinib, midostaurin, sorafenib, and quizartinib are among the most common FLT3-inhibiting agents combined with HDAC inhibitors for leukemia treatment [117, 118].

Combination with radiation therapy

In general, radiation therapy is not the primary treatment strategy for leukemia. However, combining HDAC inhibitors with radiation therapy has the potential to enhance the efficacy of palliative radiotherapy and overcome tumor resistance mechanisms in the treatment of leukemia metastases. The rationale behind this combination lies in the ability of HDAC inhibitors to modulate chromatin structure, sensitize tumor cells to radiation-induced DNA damage, and promote apoptotic cell death [119]. HDAC inhibitors alter the chromatin structure and DNA repair mechanisms, leading to increased sensitivity of metastatic cells to ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage (radiosensitization), thereby enhancing the cytotoxic effects of radiation therapy [120]. In addition, HDAC inhibitors induce apoptosis through multiple mechanisms, which synergize with radiation-induced apoptosis. Moreover, the anti-angiogenesis effects of HDAC inhibitors enhance the efficacy of radiation therapy by reducing tumor blood supply and oxygenation to metastatic tumor cells [121]. However, the current evidence regarding the clinical applicability of this combination strategy is limited.

Combination with other epigenetic modifiers

Combining HDAC inhibitors with other epigenetic modifiers, such as DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors or bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) protein inhibitors, could modulate multiple layers of epigenetic regulation and achieve synergistic antitumor effects [122–124].

DNMT inhibiting azacitidine and decitabine are among the common hypomethylating agents, recommended for leukemia combination therapy with HDAC inhibitors [125]. A recent preclinical study has demonstrated that combining decitabine and HDAC inhibition resulted in significant downregulation of both oncogenes and the epigenetic modifiers often overexpressed in leukemia [126]. Preclinical studies have also confirmed that combining HDAC inhibitors with DNMT inhibiting agents or BET inhibitors could lead to an enhanced reprogramming of gene expression, induction of differentiation, and inhibition of leukemic cell proliferation [127, 128]. Clinical trials investigating the combination of HDAC inhibitors with epigenetic modifiers in leukemia patients are still ongoing, aiming to assess safety, efficacy, and potential biomarkers of response.

Ongoing research

Several trials are currently ongoing to determine the effectiveness and safety of HDAC inhibitors in the treatment of leukemia. Most of the ongoing studies focus on adding HDAC inhibitors as an arm of a combined protocol for treating leukemia [129, 130]. Table 3 summarizes the ongoing trials of HDAC inhibitors monotherapy and combination therapy for leukemia treatment.

Table 3.

Ongoing trials on the safety and effectiveness of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in treatment of leukemia (clinicaltrials.gov)

| Trial ID | Country | Study design | Study population | Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03843528 | USA | Dose-finding phase I trial | Children (< 21) undergoing allogeneic HCT for Myeloid Malignancies (AML, MDS, JMML, MPAL) | Vorinostat in combination with low-dose azacitidine |

| NCT00392353 | USA | Phase I/II trial | Adult patients with MDS or AML | Vorinostat, in combination with 5AC |

| NCT03842696 | USA | Phase I/II multicenter trial | Children, adolescents, and young adults undergoing allogeneic BMT (GVHD prophylaxis) | Vorinostat and tacrolimus (or cyclosporine), methotrexate, MMF, cyclophosphamide |

| NCT05317403 | USA | Phase I trial | Pediatric and young adult patients relapsed and refractory AML | Vorinostat, venetoclax, and 5AC, in addition to cytarabine, fludarabine, and filgrastim |

| NCT01522976 | USA, Canada | Randomized phase II/III trial | Higher-risk MDS and CMML adult patients | 5AC alone or in combination with lenalidomide or vorinostat |

| NCT02386800 | International | Open-label, multicenter, phase IV trial | Adult/pediatric patients with prior completed global Novartis or Incyte-sponsored studies (Myelofibrosis, PV, GVHD, AML, thalassemia) | Panobinostat and ruxolitinib |

| NCT02506959 | USA | Phase II trial | Adult patients with refractory/relapsed Myeloma | Panobinostat with high-dose gemcitabine/busulfan/melphalan with ASCT |

| NCT03772925 | USA | Multicenter phase I trial | Relapsed/refractory AML/MDS adult patients | Pevonedistat and belinostat |

| NCT02737046 | USA | Phase II trial | Adult patients with ATL | Belinostat in combination with zidovudine, interferon-Alfa-2b, pegylated interferon-alfa |

| NCT02787369 | USA | Phase Ib trial | Adult patients with relapsed CLL | Ricolinostat (ACY-1215), in combination with ibrutinib and idelalisib |

| NCT01638533 | USA, Canada | Phase I trial | Adult patients with lymphomas, CLL, and selected solid tumors | Romidepsin |

| NCT03564470 | China | Open-label, multicenter phase II/III trial | Adult Ph-like ALL patients | Chidamide and dasatinib |

| NCT05881265 | China | Multicenter phase II trial | Patients with ATRA- and Arsenic-resistant APL | Chidamide and venetoclax |

| NCT06220487 | China | Open-label single-arm phase II trial | Patients with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL | Chidamide with prednisone, olverembatinib, and blinatumomab |

| NCT01305499 | USA | Randomized phase II trial | Elderly patients with AML | Entinostat, in combination with 5AC |

| NCT02553460 (TINI I) | USA, Canada | Phase I/II trial | Infants with ALL | Total therapy (vorinostat, ITMHA, dexamethasone, mitoxantrone, pegaspargase, asparaginase erwinia, chrysanthemi, bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, mercaptopurine, methotrexate, leucovorin calcium, cytarabine, etoposide, vincristine) |

| NCT05848687 (TINI II) | USA | Phase I/II trial | Infants with ALL | Total therapy (vorinostat, with dexamethasone, mitoxantrone, PEG asparaginase, bortezomib, mercaptopurine, methotrexate, blinatumomab, and ziftomenib) |

| NCT03117751 (TINI XVII) | USA, Australia | Phase I/II trial | Infants with ALL | Total therapy (vorinostat, prednisone, vincristine, daunorubicin, pegaspargase, erwinase®, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, mercaptopurine, dasatinib, methotrexate, blinatumomab, ruxolitinib, bortezomib, dexamethasone, doxorubicin, etoposide, clofarabine, idarubicin, nelarabine, thioguanine, asparaginase erwinia chrysanthemi (recombinant)-rywn, calaspargase pegol) |

5AC 5-Azacitidine, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, APL acute promyelocytic leukemia, ASCT autologous stem cell transplant, ATL adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, ATRA all-trans retinoic acid, BMT blood and marrow transplantation, CML chronic myelocytic leukemia, CMML chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, GVHD graft versus host disease, HCT hematopoietic cell transplantation, ITMHA intrathecal methotrexate, hydrocortisone, and cytarabine, JMML juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, MMF mycophenolate mofetil, MPAL mixed-phenotype acute leukemia, Ph-like Philadelphia chromosome-like, PV polycythemia vera

Future directions

Future research endeavors regarding the potential of HDAC inhibitors in the treatment of leukemia should address the following issues:

Combination therapies: The synergistic effects of HDAC inhibitors with available novel and conventional cancer therapies, including other targeted agents, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy, in order to improve efficacy and minimize resistance.

Biomarker identification: Identifying predictive biomarkers for response to HDAC inhibitor therapy, in order to select leukemia patients who are most likely to benefit from HDAC inhibitor therapy and monitoring treatment response.

Epigenetic profiling: Utilizing epigenetic profiling to stratify leukemia patients based on their epigenetic signatures and tailor treatment approaches accordingly.

Developing next-generation HDAC inhibitors: Designing selective HDAC inhibitors with improved potency, pharmacokinetics, and safety profiles to overcome limitations associated with current agents.

Immunomodulatory effects: Exploring the immunomodulatory effects of HDAC inhibitors, including their impact on the tumor microenvironment and immune checkpoint regulation, to enhance antileukemic immune responses.

Conclusion

Histone deacetylase inhibitors represent a promising therapeutic strategy for different leukemia subtypes by targeting epigenetic dysregulation implicated in leukemogenesis. While significant progress has been made in understanding their mechanisms of action and clinical efficacy, challenges such as drug resistance and life-limiting side effects still persist. Ongoing research efforts focused on combination therapies, biomarker identification, and next-generation HDAC inhibitors hold promise for improving outcomes in patients with hematological malignancies.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

MSH: Conceptualization, data curation, visualization, writing—original draft. ZS: data curation, writing—review & editing. MAA: data curation, writing—original draft. YVG: data curation, writing—original draft. MA: visualization, writing—review & editing.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The lead author is currently an associate editor of the European Journal of Medical Research. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tebbi CK. Etiology of acute leukemia: a review. Cancers. 2021. 10.3390/cancers13092256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt JA, Hornhardt S, Erdmann F, Sánchez-García I, Fischer U, Schüz J, et al. Risk factors for childhood leukemia: radiation and beyond. Front Public Health. 2021;9: 805757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shadman M. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a review. JAMA. 2023;329(11):918–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke Rachel T, Van den Bruel A, Bankhead C, Mitchell CD, Phillips B, Thompson MJ. Clinical presentation of childhood leukaemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Childhood. 2016;101(10):894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inaba H, Pui CH. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Med. 2021;10(9):1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du M, Chen W, Liu K, Wang L, Hu Y, Mao Y, et al. The global burden of leukemia and its attributable factors in 204 countries and territories: findings from the global burden of disease 2019 study and projections to 2030. J Oncol. 2022;2022:1612702. 10.1155/2022/1612702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao C, Dong H, Xu Q, Zhang Y. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in cancer: a patent review (2017-present). Expert Opin Ther Patents. 2020;30(4):263–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li G, Tian Y, Zhu WG. The roles of histone deacetylases and their inhibitors in cancer therapy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8: 576946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parveen R, Harihar D, Chatterji BP. Recent histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Cancer. 2023;129(21):3372–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verza FA, Das U, Fachin AL, Dimmock JR, Marins M. Roles of histone deacetylases and inhibitors in anticancer therapy. Cancers. 2020;12(6):1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HT, Oh S, Yoo H, Kwon YW. The key role of DNA methylation and histone acetylation in epigenetics of atherosclerosis. J Lipid Atheroscl. 2020;9(3):419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruzic D, Djoković N, Srdić-Rajić T, Echeverria C, Nikolic K, Santibanez JF. Targeting histone deacetylases: opportunities for cancer treatment and chemoprevention. Pharmaceutics. 2022. 10.3390/pharmaceutics14010209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Seto E. HDACs and HDAC inhibitors in cancer development and therapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016. 10.1101/cshperspect.a026831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ocker M. Deacetylase inhibitors—focus on non-histone targets and effects. World J Biol Chem. 2010;1(5):55–61. 10.4331/wjbc.v1.i5.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.San José-Enériz E, Gimenez-Camino N, Agirre X, Prosper F. HDAC inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers. 2019. 10.3390/cancers11111794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alseksek RK, Ramadan WS, Saleh E, El-Awady R. The role of HDACs in the response of cancer cells to cellular stress and the potential for therapeutic intervention. Int J Mol Sci. 2022. 10.3390/ijms23158141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong P, Wang Y, Jing Y. Apoptosis induction by histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer cells: role of Ku70. Int J Mol Sci. 2019. 10.3390/ijms20071601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Zhong Q. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and cell death. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS. 2014;71(20):3885–901. 10.1007/s00018-014-1656-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gammoh N, Lam D, Puente C, Ganley I, Marks PA, Jiang X. Role of autophagy in histone deacetylase inhibitor-induced apoptotic and nonapoptotic cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(17):6561–5. 10.1073/pnas.1204429109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghelli Luserna di Rora A, Iacobucci I, Martinelli G. The cell cycle checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of leukemias. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):77. 10.1186/s13045-017-0443-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephen NM, Deepika UR, Maradagi T, Sugawara T, Hirata T, Ganesan P. Insight on the cellular and molecular basis of blood vessel formation: a specific focus on tumor targets and therapy. MedComm Oncol. 2023;2(1): e22. 10.1002/mog2.22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis L, Hammers H, Pili R. Targeting tumor angiogenesis with histone deacetylase inhibitors. Cancer Lett. 2009;280(2):145–53. 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin G, Bausch D, Knightly T, Liu Z, Li Y, Liu B, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors enhance endothelial cell sprouting angiogenesis in vitro. Surgery. 2011;150(3):429–35. 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuljaca S, Liu T, Tee AEL, Haber M, Norris MD, Dwarte T, et al. Enhancing the anti-angiogenic action of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Mol Cancer. 2007;6(1):68. 10.1186/1476-4598-6-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HJ, Bae SC. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: molecular mechanisms of action and clinical trials as anti-cancer drugs. Am J Transl Res. 2011;3(2):166–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Y, Shen M, Wu L, Yang H, Yao Y, Yang Q, et al. Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment: accomplices of tumor progression? Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(9):587. 10.1038/s41419-023-06110-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karagiannis D, Rampias T. HDAC inhibitors: dissecting mechanisms of action to counter tumor heterogeneity. Cancers. 2021. 10.3390/cancers13143575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bose P, Dai Y, Grant S. Histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACI) mechanisms of action: emerging insights. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;143(3):323–36. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang B, Lyu J, Yang EJ, Liu Y, Wu C, Pardeshi L, et al. Class I histone deacetylase inhibition is synthetic lethal with BRCA1 deficiency in breast cancer cells. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2020;10(4):615–27. 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mrakovcic M, Bohner L, Hanisch M, Fröhlich LF. Epigenetic targeting of autophagy via HDAC inhibition in tumor cells: role of p53. Int J Mol Sci. 2018. 10.3390/ijms19123952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park SY, Kim JS. A short guide to histone deacetylases including recent progress on class II enzymes. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52(2):204–12. 10.1038/s12276-020-0382-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seto E, Yoshida M. Erasers of histone acetylation: the histone deacetylase enzymes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(4): a018713. 10.1101/cshperspect.a018713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porter NJ, Christianson DW. Structure, mechanism, and inhibition of the zinc-dependent histone deacetylases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2019;59:9–18. 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schemies J, Uciechowska U, Sippl W, Jung M. NAD(+)-dependent histone deacetylases (sirtuins) as novel therapeutic targets. Med Res Rev. 2010;30(6):861–89. 10.1002/med.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdallah DI, de Araujo ED, Patel NH, Hasan LS, Moriggl R, Krämer OH, et al. Medicinal chemistry advances in targeting class I histone deacetylases. Explor Target Anti-Tumor Ther. 2023;4(4):757–79. 10.37349/etat.2023.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan J, Cang S, Ma Y, Petrillo RL, Liu D. Novel histone deacetylase inhibitors in clinical trials as anti-cancer agents. J Hematol Oncol. 2010;3:5. 10.1186/1756-8722-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chao MP. Treatment challenges in the management of relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma - novel and emerging therapies. Cancer Manag Res. 2013;5:251–69. 10.2147/cmar.s34273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moran B, Davern M, Reynolds JV, Donlon NE, Lysaght J. The impact of histone deacetylase inhibitors on immune cells and implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2023;559: 216121. 10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin HS, Choi J, Lee J, Lee SY. Histone deacetylase as a valuable predictive biomarker and therapeutic target in immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2022;54(2):458–68. 10.4143/crt.2021.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Q, Wang S, Chen J, Yu Z. Histone deacetylases (HDACs) guided novel therapies for T-cell lymphomas. Int J Med Sci. 2019;16(3):424–42. 10.7150/ijms.30154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y, Zhang G, Wang Y, Ye L, Peng L, Shi R, et al. Current treatment strategies targeting histone deacetylase inhibitors in acute lymphocytic leukemia: a systematic review. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1324859. 10.3389/fonc.2024.1324859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang T, Wang F, Elhassan RM, Cheng Y, Tang X, Chen W, et al. Targeting histone deacetylases for cancer therapy: trends and challenges. Acta pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2023;13(6):2425–63. 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gryder BE, Sodji QH, Oyelere AK. Targeted cancer therapy: giving histone deacetylase inhibitors all they need to succeed. Future Med Chem. 2012;4(4):505–24. 10.4155/fmc.12.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suraweera A, O’Byrne KJ, Richard DJ. Combination therapy with histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) for the treatment of cancer: achieving the full therapeutic potential of HDACi. Front Oncol. 2018. 10.3389/fonc.2018.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen J, Ren JJ, Cai J, Wang X. Efficacy and safety of HDACIs in the treatment of metastatic or unresectable renal cell carcinoma with a clear cell phenotype: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2021;100(31): e26788. 10.1097/md.0000000000026788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao X, Shen L, Li X, Liu J. Efficacy and toxicity of histone deacetylase inhibitors in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18(2):1057–68. 10.3892/etm.2019.7704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sochacka-Ćwikła A, Mączyński M, Regiec A. FDA-approved drugs for hematological malignancies-the last decade review. Cancers. 2021. 10.3390/cancers14010087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ludwig H, Delforge M, Facon T, Einsele H, Gay F, Moreau P, et al. Prevention and management of adverse events of novel agents in multiple myeloma: a consensus of the European Myeloma Network. Leukemia. 2018;32(7):1542–60. 10.1038/s41375-018-0040-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coppola C, Rienzo A, Piscopo G, Barbieri A, Arra C, Maurea N. Management of QT prolongation induced by anti-cancer drugs: target therapy and old agents. Different algorithms for different drugs. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;63:135–43. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agarwal MA, Sridharan A, Pimentel RC, Markowitz SM, Rosenfeld LE, Fradley MG, et al. Ventricular arrhythmia in cancer patients: mechanisms, treatment strategies and future avenues. Arrhyth Electrophysiol Rev. 2023;12: e16. 10.15420/aer.2023.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wawruszak A, Borkiewicz L, Okon E, Kukula-Koch W, Afshan S, Halasa M. Vorinostat (SAHA) and breast cancer: an overview. Cancers. 2021. 10.3390/cancers13184700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohapatra TK, Nayak RR, Ganeshpurkar A, Tiwari P, Kumar D. Opportunities and difficulties in the repurposing of HDAC inhibitors as antiparasitic agents. Drugs Drug Candidates. 2024;3(1):70–101. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bubna AK. Vorinostat-an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60(4):419. 10.4103/0019-5154.160511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Y, Zhang M, Wang Y. The roles of histone modifications in tumorigenesis and associated inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Center. 2022;2(4):277–90. 10.1016/j.jncc.2022.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siegel D, Hussein M, Belani C, Robert F, Galanis E, Richon VM, et al. Vorinostat in solid and hematologic malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2009;2:31. 10.1186/1756-8722-2-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mann BS, Johnson JR, Cohen MH, Justice R, Pazdur R. FDA approval summary: vorinostat for treatment of advanced primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncologist. 2007;12(10):1247–52. 10.1634/theoncologist.12-10-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lohitesh K, Saini H, Srivastava A, Mukherjee S, Roy A, Chowdhury R. Autophagy inhibition potentiates SAHA-mediated apoptosis in glioblastoma cells by accumulation of damaged mitochondria. Oncol Rep. 2018;39(6):2787–96. 10.3892/or.2018.6373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mayr C, Kiesslich T, Erber S, Bekric D, Dobias H, Beyreis M, et al. HDAC screening identifies the HDAC class I inhibitor romidepsin as a promising epigenetic drug for biliary tract cancer. Cancers. 2021. 10.3390/cancers13153862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Petrich A, Nabhan C. Use of class I histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin in combination regimens. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(8):1755–65. 10.3109/10428194.2016.1160082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cappellacci L, Perinelli DR, Maggi F, Grifantini M, Petrelli R. Recent progress in histone deacetylase inhibitors as anticancer agents. Curr Med Chem. 2020;27(15):2449–93. 10.2174/0929867325666181016163110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Valdez BC, Brammer JE, Li Y, Murray D, Liu Y, Hosing C, et al. Romidepsin targets multiple survival signaling pathways in malignant T cells. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5(10): e357. 10.1038/bcj.2015.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barbarotta L, Hurley K. Romidepsin for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2015;6(1):22–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stein RA. Epigenetic therapies—a new direction in clinical medicine. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68(7):802–11. 10.1111/ijcp.12436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pojani E, Barlocco D. Romidepsin (FK228), a histone deacetylase inhibitor and its analogues in cancer chemotherapy. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28(7):1290–303. 10.2174/0929867327666200203113926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bondarev AD, Attwood MM, Jonsson J, Chubarev VN, Tarasov VV, Schiöth HB. Recent developments of HDAC inhibitors: Emerging indications and novel molecules. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87(12):4577–97. 10.1111/bcp.14889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hrgovic I, Doll M, Kleemann J, Wang XF, Zoeller N, Pinter A, et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin a decreases lymphangiogenesis by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest via p21-dependent pathways. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):763. 10.1186/s12885-016-2807-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang B, Wang XB, Chen LY, Huang L, Dong RZ. Belinostat-induced apoptosis and growth inhibition in pancreatic cancer cells involve activation of TAK1-AMPK signaling axis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;437(1):1–6. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.El Omari N, Bakrim S, Khalid A, Albratty M, Abdalla AN, Lee LH, et al. Anticancer clinical efficiency and stochastic mechanisms of belinostat. Biomed Pharmacother Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;165: 115212. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kusaczuk M, Krętowski R, Stypułkowska A, Cechowska-Pasko M. Molecular and cellular effects of a novel hydroxamate-based HDAC inhibitor—belinostat—in glioblastoma cell lines: a preliminary report. Invest New Drugs. 2016;34(5):552–64. 10.1007/s10637-016-0372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Singh A, Patel VK, Jain DK, Patel P, Rajak H. Panobinostat as pan-deacetylase inhibitor for the treatment of pancreatic cancer: recent progress and future prospects. Oncol Ther. 2016;4(1):73–89. 10.1007/s40487-016-0023-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sivaraj D, Green MM, Gasparetto C. Panobinostat for the management of multiple myeloma. Future Oncol (London, England). 2017;13(6):477–88. 10.2217/fon-2016-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pan D, Mouhieddine TH, Upadhyay R, Casasanta N, Lee A, Zubizarreta N, et al. Outcomes with panobinostat in heavily pretreated multiple myeloma patients. Semin Oncol. 2023;50(1):40–8. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2023.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raedler LA. Farydak (Panobinostat): first HDAC inhibitor approved for patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9:84–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jiang XJ, Huang KK, Yang M, Qiao L, Wang Q, Ye JY, et al. Synergistic effect of panobinostat and bortezomib on chemoresistant acute myelogenous leukemia cells via AKT and NF-κB pathways. Cancer Lett. 2012;326(2):135–42. 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Morabito F, Voso MT, Hohaus S, Gentile M, Vigna E, Recchia AG, et al. Panobinostat for the treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25(9):1117–31. 10.1080/13543784.2016.1216971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kobayashi Y, Gélinas C, Dougherty JP. Histone deacetylase inhibitors containing a benzamide functional group and a pyridyl cap are preferentially effective human immunodeficiency virus-1 latency-reversing agents in primary resting CD4+ T cells. J Gen Virol. 2017;98(4):799–809. 10.1099/jgv.0.000716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ning ZQ, Li ZB, Newman MJ, Shan S, Wang XH, Pan DS, et al. Chidamide (CS055/HBI-8000): a new histone deacetylase inhibitor of the benzamide class with antitumor activity and the ability to enhance immune cell-mediated tumor cell cytotoxicity. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69(4):901–9. 10.1007/s00280-011-1766-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yuan XG, Huang YR, Yu T, Jiang HW, Xu Y, Zhao XY. Chidamide, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, induces growth arrest and apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells in a caspase-dependent manner. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(1):411–9. 10.3892/ol.2019.10301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.He Y, Jiang D, Zhang K, Zhu Y, Zhang J, Wu X, et al. Chidamide, a subtype-selective histone deacetylase inhibitor, enhances Bortezomib effects in multiple myeloma therapy. J Cancer. 2021;12(20):6198–208. 10.7150/jca.61602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiang X, Jiang L, Cheng J, Chen F, Ni J, Yin C, et al. Inhibition of EZH2 by chidamide exerts antileukemia activity and increases chemosensitivity through Smo/Gli-1 pathway in acute myeloid leukemia. J Transl Med. 2021;19(1):117. 10.1186/s12967-021-02789-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu W, Zhao D, Liu T, Niu T, Song Y, Xu W, et al. A multi-center, real-world study of chidamide for patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphomas in China. Front Oncol. 2021;11: 750323. 10.3389/fonc.2021.750323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Connolly RM, Rudek MA, Piekarz R. Entinostat: a promising treatment option for patients with advanced breast cancer. Future Oncol (London, England). 2017;13(13):1137–48. 10.2217/fon-2016-0526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zeyn Y, Hausmann K, Halilovic M, Beyer M, Ibrahim HS, Brenner W, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors modulate hormesis in leukemic cells with mutant FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3. Leukemia. 2023;37(11):2319–23. 10.1038/s41375-023-02036-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhou Z, Fang Q, Li P, Ma D, Zhe N, Ren M, et al. Entinostat combined with Fludarabine synergistically enhances the induction of apoptosis in TP53 mutated CLL cells via the HDAC1/HO-1 pathway. Life Sci. 2019;232: 116583. 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Prebet T, Sun Z, Ketterling RP, Zeidan A, Greenberg P, Herman J, et al. Azacitidine with or without Entinostat for the treatment of therapy-related myeloid neoplasm: further results of the E1905 North American Leukemia Intergroup study. Br J Haematol. 2016;172(3):384–91. 10.1111/bjh.13832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Connolly RM, Li H, Jankowitz RC, Zhang Z, Rudek MA, Jeter SC, et al. Combination epigenetic therapy in advanced breast cancer with 5-azacitidine and entinostat: a phase II National Cancer Institute/Stand Up to Cancer Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(11):2691–701. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-16-1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Boumber Y, Younes A, Garcia-Manero G. Mocetinostat (MGCD0103): a review of an isotype-specific histone deacetylase inhibitor. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20(6):823–9. 10.1517/13543784.2011.577737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Younes A, Oki Y, Bociek RG, Kuruvilla J, Fanale M, Neelapu S, et al. Mocetinostat for relapsed classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(13):1222–8. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70265-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mottamal M, Zheng S, Huang TL, Wang G. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in clinical studies as templates for new anticancer agents. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2015;20(3):3898–941. 10.3390/molecules20033898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pinazza M, Borga C, Agnusdei V, Minuzzo S, Fossati G, Paganin M, et al. An immediate transcriptional signature associated with response to the histone deacetylase inhibitor Givinostat in T acute lymphoblastic leukemia xenografts. Cell Death Dis. 2016;6(1): e2047. 10.1038/cddis.2015.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chifotides HT, Bose P, Verstovsek S. Givinostat: an emerging treatment for polycythemia vera. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2020;29(6):525–36. 10.1080/13543784.2020.1761323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Roy R, Ria T, RoyMahaPatra D, Sk UH. Single inhibitors versus dual inhibitors: role of HDAC in cancer. ACS Omega. 2023;8(19):16532–44. 10.1021/acsomega.3c00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Landsburg DJ, Barta SK, Ramchandren R, Batlevi C, Iyer S, Kelly K, et al. Fimepinostat (CUDC-907) in patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B cell and high-grade B-cell lymphoma: report of a phase 2 trial and exploratory biomarker analyses. Br J Haematol. 2021;195(2):201–9. 10.1111/bjh.17730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jo JH, Jung DE, Lee HS, Park SB, Chung MJ, Park JY, et al. A phase I/II study of ivaltinostat combined with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with untreated locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2022;151(9):1565–77. 10.1002/ijc.34144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Moreira-Silva F, Camilo V, Gaspar V, Mano JF, Henrique R, Jerónimo C. Repurposing old drugs into new epigenetic inhibitors: promising candidates for cancer treatment? Pharmaceutics. 2020. 10.3390/pharmaceutics12050410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xia Y, Sun M, Huang H, Jin WL. Drug repurposing for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):92. 10.1038/s41392-024-01808-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bouyahya A, El Omari N, Bakha M, Aanniz T, El Menyiy N, El Hachlafi N, et al. Pharmacological properties of trichostatin A, focusing on the anticancer potential: a comprehensive review. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(10):1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Peiffer L, Poll-Wolbeck SJ, Flamme H, Gehrke I, Hallek M, Kreuzer KA. Trichostatin A effectively induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells via inhibition of Wnt signaling and histone deacetylation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(8):1283–93. 10.1007/s00432-014-1689-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chambers AE, Banerjee S, Chaplin T, Dunne J, Debernardi S, Joel SP, et al. Histone acetylation-mediated regulation of genes in leukaemic cells. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990). 2003;39(8):1165–75. 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kwon SH, Ahn SH, Kim YK, Bae GU, Yoon JW, Hong S, et al. Apicidin, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, induces apoptosis and Fas/Fas ligand expression in human acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(3):2073–80. 10.1074/jbc.M106699200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu L, Liu H, Liu L, Huang Q, Yang C, Cheng P, et al. Apicidin confers promising therapeutic effect on acute myeloid leukemia cells via increasing QPCT expression. Cancer Biol Ther. 2023;24(1):2228497. 10.1080/15384047.2023.2228497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fredly H, Gjertsen BT, Bruserud Ø. Histone deacetylase inhibition in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: the effects of valproic acid on leukemic cells, and the clinical and experimental evidence for combining valproic acid with other antileukemic agents. Clin Epigenet. 2013;5(1):12. 10.1186/1868-7083-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bug G, Schwarz K, Schoch C, Kampfmann M, Henschler R, Hoelzer D, et al. Effect of histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid on progenitor cells of acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2007;92(4):542–5. 10.3324/haematol.10758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wen J, Chen Y, Yang J, Dai C, Yu S, Zhong W, et al. Valproic acid increases CAR T cell cytotoxicity against acute myeloid leukemia. J ImmunoTher Cancer. 2023;11(7): e006857. 10.1136/jitc-2023-006857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jenke R, Reßing N, Hansen FK, Aigner A, Büch T. Anticancer therapy with HDAC inhibitors: mechanism-based combination strategies and future perspectives. Cancers. 2021;13(4):634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Eslami M, Memarsadeghi O, Davarpanah A, Arti A, Nayernia K, Behnam B. Overcoming chemotherapy resistance in metastatic cancer: a comprehensive review. Biomedicines. 2024;12(1):183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hontecillas-Prieto L, Flores-Campos R, Silver A, de Álava E, Hajji N, García-Domínguez DJ. Synergistic enhancement of cancer therapy using HDAC inhibitors: opportunity for clinical trials. Front Genet. 2020;11: 578011. 10.3389/fgene.2020.578011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.McCaw TR, Randall TD, Forero A, Buchsbaum DJ. Modulation of antitumor immunity with histone deacetylase inhibitors. Immunotherapy. 2017;9(16):1359–72. 10.2217/imt-2017-0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shanmugam G, Rakshit S, Sarkar K. HDAC inhibitors: Targets for tumor therapy, immune modulation and lung diseases. Transl Oncol. 2022;16: 101312. 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hasanali ZS, Saroya BS, Stuart A, Shimko S, Evans J, Vinod SM, et al. Epigenetic therapy overcomes treatment resistance in T cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(293): 293ra102. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Weber JS, Levinson BA, Laino AS, Pavlick AC, Woods DM. Clinical and immune correlate results from a phase 1b study of the histone deacetylase inhibitor mocetinostat with ipilimumab and nivolumab in unresectable stage III/IV melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2022;32(5):324–33. 10.1097/cmr.0000000000000818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hosseini MS, Akbarzadeh MA, Jadidi-Niaragh F. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Macrophage Polarization in Cancer Immunotherapy. Critical Developments in Cancer Immunotherapy. IGI Global. 2024;157–204. 10.4018/979-8-3693-3976-3.ch005.

- 113.Chen X, Pan X, Zhang W, Guo H, Cheng S, He Q, et al. Epigenetic strategies synergize with PD-L1/PD-1 targeted cancer immunotherapies to enhance antitumor responses. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10(5):723–33. 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wachholz V, Mustafa AM, Zeyn Y, Henninger SJ, Beyer M, Dzulko M, et al. Inhibitors of class I HDACs and of FLT3 combine synergistically against leukemia cells with mutant FLT3. Arch Toxicol. 2022;96(1):177–93. 10.1007/s00204-021-03174-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hu X, Li J, Fu M, Zhao X, Wang W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):402. 10.1038/s41392-021-00791-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Takahashi S. Combination therapies with kinase inhibitors for acute myeloid leukemia treatment. Hematol Rep. 2023;15(2):331–46. 10.3390/hematolrep15020035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhao JC, Agarwal S, Ahmad H, Amin K, Bewersdorf JP, Zeidan AM. A review of FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Rev. 2022;52: 100905. 10.1016/j.blre.2021.100905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Majothi S, Adams D, Loke J, Stevens SP, Wheatley K, Wilson JS. FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukaemia: assessment of clinical effectiveness, adverse events and future research—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):285. 10.1186/s13643-020-01540-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Thurn KT, Thomas S, Moore A, Munster PN. Rational therapeutic combinations with histone deacetylase inhibitors for the treatment of cancer. Future Oncol (London, England). 2011;7(2):263–83. 10.2217/fon.11.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Karagiannis TC, El-Osta A. Modulation of cellular radiation responses by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2006;25(28):3885–93. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ling R, Wang J, Fang Y, Yu Y, Su Y, Sun W, et al. HDAC-an important target for improving tumor radiotherapy resistance. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1193637. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1193637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kumar A, Emdad L, Fisher PB, Das SK. Chapter three—targeting epigenetic regulation for cancer therapy using small molecule inhibitors. In: Landry JW, Das SK, Fisher PB, editors. Advances in cancer research, vol. 158. Academic Press; 2023. p. 73–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Pathania R, Ramachandran S, Mariappan G, Thakur P, Shi H, Choi JH, et al. Combined inhibition of DNMT and HDAC blocks the tumorigenicity of cancer stem-like cells and attenuates mammary tumor growth. Can Res. 2016;76(11):3224–35. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-15-2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Huang W, Zhu Q, Shi Z, Tu Y, Li Q, Zheng W, et al. Dual inhibitors of DNMT and HDAC induce viral mimicry to induce antitumour immunity in breast cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10(1):143. 10.1038/s41420-024-01895-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Flotho C, Claus R, Batz C, Schneider M, Sandrock I, Ihde S, et al. The DNA methyltransferase inhibitors azacitidine, decitabine and zebularine exert differential effects on cancer gene expression in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2009;23(6):1019–28. 10.1038/leu.2008.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Blagitko-Dorfs N, Schlosser P, Greve G, Pfeifer D, Meier R, Baude A, et al. Combination treatment of acute myeloid leukemia cells with DNMT and HDAC inhibitors: predominant synergistic gene downregulation associated with gene body demethylation. Leukemia. 2019;33(4):945–56. 10.1038/s41375-018-0293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhou M, Yuan M, Zhang M, Lei C, Aras O, Zhang X, et al. Combining histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) with other therapies for cancer therapy. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;226: 113825. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Doroshow DB, Eder JP, LoRusso PM. BET inhibitors: a novel epigenetic approach. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1776–87. 10.1093/annonc/mdx157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Borcoman E, Kamal M, Marret G, Dupain C, Castel-Ajgal Z, Le Tourneau C. HDAC Inhibition to Prime Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancers. 2021. 10.3390/cancers14010066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wang F, Jin Y, Wang M, Luo HY, Fang WJ, Wang YN, et al. Combined anti-PD-1, HDAC inhibitor and anti-VEGF for MSS/pMMR colorectal cancer: a randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 2024;30(4):1035–43. 10.1038/s41591-024-02813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gao M, Chen G, Wang H, Xie B, Hu L, Kong Y, et al. Therapeutic potential and functional interaction of carfilzomib and vorinostat in T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(20):29102–15. 10.18632/oncotarget.8667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Chao MW, Lai MJ, Liou JP, Chang YL, Wang JC, Pan SL, et al. The synergic effect of vincristine and vorinostat in leukemia in vitro and in vivo. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:82. 10.1186/s13045-015-0176-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]