Abstract

Objective

To explore the structural and social co-factors that shape the early lives of women who enter sex work in Nairobi, Kenya.

Design

Thematic analysis of qualitative data collected as part of the Maisha Fiti study among female sex workers (FSWs) in Nairobi.

Participants and measures

FSWs aged 18–45 years were randomly selected from seven Sex Workers Outreach Programme clinics in Nairobi and participated in baseline behavioural–biological surveys. Participants in this qualitative study were randomly selected from the Maisha Fiti study cohort and were interviewed between October 2019 and July 2020. Women described their lives from childhood, covering topics including sex work, violence and financial management.

Results

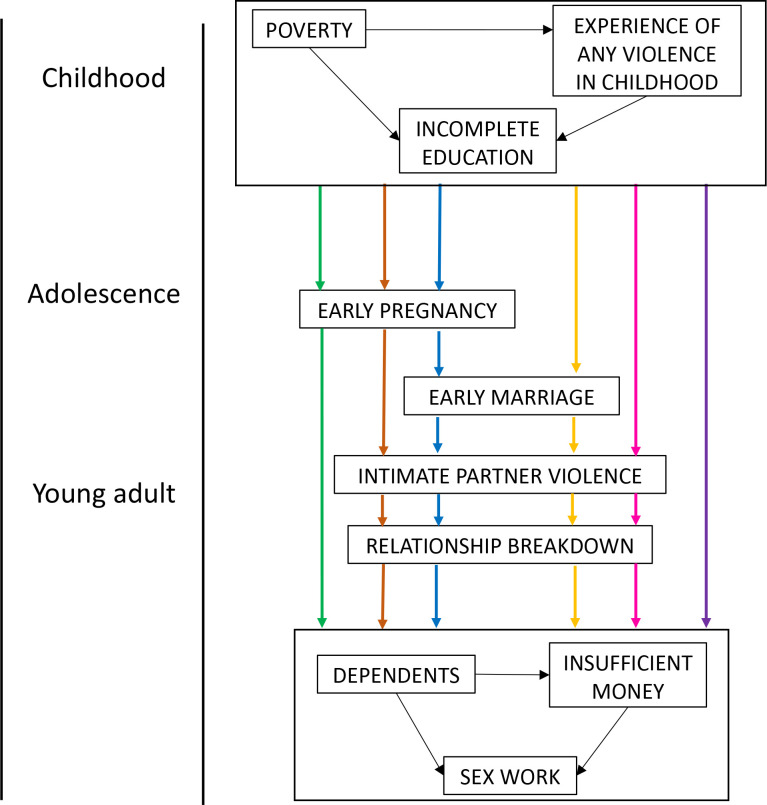

48 out of 1003 Maisha Fiti participants participated in the in-depth qualitative interviews. FSWs described how physical and sexual violence, poverty and incomplete education in their childhood and adolescence intertwined with early pregnancy, marriage, intimate partner violence and relationship breakdown in their adolescence and early adulthood. The data analysis found clear syndemic relationships between these risk factors, particularly childhood violence, poverty and incomplete education and highlighted pathways leading to financial desperation and caring for dependents, and subsequent entry into sex work. Women perceived sex work as risky and most would prefer alternative work if possible, but it provided them with some financial independence and agency.

Conclusions

This is the first study in Kenya to qualitatively explore the early lives of sex workers from a syndemic perspective. This method identified the pivotal points of (1) leaving school early due to poverty or pregnancy, (2) breakdown of early intimate relationships and (3) women caring for dependents on their own. Complex, multi-component structural interventions before these points could help increase school retention, reduce teenage pregnancy, tackle violence, support young mothers and reduce entry into sex work and the risk that it entails by expanding livelihood options.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, EPIDEMIOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study adds to the limited research on childhood and adolescent experiences of female sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa.

The study methodology enabled capture of childhood experiences in detail due to the use of semi-structured interviews and probing questions.

Each transcript was accompanied by a script written by the interviewer, capturing non-verbal cues and their understanding of emerging narratives.

Themes of childhood physical and sexual violence and intimate partner violence were key factors of this study; it is possible that experiences may have been under-reported due to the normalisation of violence.

Introduction

Female sex workers (FSWs) can be defined as women who exchange sex for money or goods with explicit acknowledgement and without any mention of a normatively recognised relationship.1 FSWs can experience increased risk of acquiring HIV and sexually transmitted infections, sexual and physical violence, poor mental health and high levels of alcohol and substance use.2 3 They can also experience high levels of stigma, discrimination, social marginalisation and barriers to accessing health and social services, which in turn can amplify their vulnerability to health and social risks.4–6 Adverse experiences during childhood and adolescence can have consequences in later life and can influence future risk behaviours.7–10 Violence experienced during childhood has been shown to be directly related to sex work initiation.11–15 FSWs often have a low level of education, with approximately one-third in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) having completed only primary education,3 16–18 compared with half of all females in the general population.19

FSWs in SSA often experience gender inequities which affect their political, economic and social opportunities.20 They can have limited prospect of formal employment or self-employment opportunities and can struggle to survive on the income from casual jobs.21–23 Many FSWs in SSA report having at least one child before entering into sex work, with first pregnancies often occurring during adolescence.22 24–27 The need to care for dependents can compound economic necessity22 28–32 and prompt the move into sex work as a means of earning a living.33

Despite introducing progressive legal structures, policies and government frameworks to empower women, Kenya is still entrenched in patriarchal sociocultural norms that can result in gender disparities.34 Boys outnumber girls in school enrolment, with the difference increasing with level of education.35 Women tend to be poorer, earn less and have less access to capital and assets to sustain their livelihoods than men.36 Experiences of violence against girls and young women are common, with 32% and 66% of young women reporting sexual and physical violence during their childhood and adolescence, respectively.37 Gate keepers that organise or facilitate sex work are criminalised nationally, and some counties including Nairobi also criminalise individual sex workers.38 Not only can FSWs face health, psychosocial and economic hardships, they can also be denied human rights and protection due to the illegal status of sex work.38

Studies reporting risk factors for entry into sex work tend to describe individual factors such as ‘economic necessity’ or ‘childhood sexual abuse’ without exploring associations between multiple factors present throughout the lives of individuals in the context of their surroundings. Macro events and complex social processes can result in a population being structurally disadvantaged, leading to vulnerabilities beyond individual control. This study conceptualises and explores the complex and multifaceted factors that shape the early lives of women who enter sex work in Nairobi, Kenya. This is particularly important in order to create interventions and/or push changes in policy toward sex work prevention, it is necessary to be able to identify adolescents who are at-risk of entering into sex work and highlight potential points of effective intervention.

Methods

Study design

This is a descriptive exploratory analysis of qualitative data collected as part of a longitudinal observational study conducted from July 2019 to March 2021.

Setting

Nairobi is the capital of Kenya and has a population of just under 4.4 million.39 An estimated 40 000 women sell sex in Nairobi, working from approximately 2000 different places.40 41 The Sex Workers Outreach Programme (SWOP) was formed in 2008 and through seven clinics provide free clinical, counselling and harm reduction services to key populations including approximately 33 000 FSWs. The clinics are managed by Partners for Health and Development in Africa and the University of Manitoba, with funding provided by CDC-PEPFAR.

Participants and recruitment

This study was part of a larger mixed methods study called ‘Maisha Fiti’, which aimed to understand the impact of social and structural factors such as violence and poor mental health on inflammation in the blood and the genital tract. The study methods have been described elsewhere.42 In brief, Maisha Fiti was advertised as ‘a study on women’s health and well-being’ to help minimise participating women being put at risk of stigma, discrimination and violence. SWOP clinic lists were used to identify all FSWs aged 18–45 years who had visited a clinic in the past 12 months, with 1200 FSWs randomly sampled from a list of 10 292, and with numbers selected proportional to each SWOP clinic size. Eligible women were telephoned by members of the research team and provided information about the study. Women interested in participating were invited to attend the study clinic where they were given a detailed participant information sheet both written and orally and undertook a urine pregnancy test. Interested women who were not pregnant or breastfeeding (as this affects host immunology) provided written informed consent and were enrolled in the study. Participants were reimbursed their transport costs for each study visit. They were also provided with clinical care and psychological support during visits, which was separate from, and did not depend on, their participation in the research. In October 2019 during the first phase of behavioural–biological data collection, 40 women who had completed baseline behavioural and biological surveys were randomly selected to take part in in-depth interviews (IDIs). This sample size was deemed sufficient to expect data saturation based on previous experience and the time and resources available. There was by chance an under-representation of younger women in the random sampling, and therefore in July 2020, 8 additional women were randomly selected to be interviewed from all women aged 18–24 years who were enrolled in the study.

Research team and data collection

The Maisha Fiti study field team comprised of a study coordinator, two female qualitative social scientists, two research assistants, three community liaison members, a clinical team (doctor, two nurses and a counsellor) and nine peer educators who were all experienced in working with FSWs in Nairobi. Prior to the study start, the study team received three weeks of intensive training on study modules including client confidentiality, violence, mental health, and substance and alcohol misuse. The research tools were pretested and amended following feedback from the team. The IDIs lasting 60–90 min were conducted in the language of choice of the participant (either Swahili or English) by one of two female social scientists in private rooms and were audio-recorded when consent was provided for this. For one participant that declined recording, an interview script was written up from detailed notes. During the IDIs, women were asked to provide detailed life stories, narrating events and experiences about their lives. Topics in the interview guide included introductions, financial management, sex work, alcohol and substance use, factors associated with gender-based violence, experiences of violence, mental health and aspirations (online supplemental file 1).

bmjopen-2022-068886supp001.pdf (87.8KB, pdf)

After completing each interview, interviewers developed a ‘script’, which detailed non-verbal cues and the researcher’s recall of the interview.43 The research team, including the PIs and interviewers, met after each interview to debrief and discuss the interviews and scripts. Audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim and Swahili transcripts were translated into English by a member of the research team. The scripts complemented the transcripts and were analysed in the same manner as the transcripts.

Analysis

The thematic analysis process followed that described by Braun and Clarke (2006)44 and began while the interviews were still ongoing. The debrief meetings provided a multi-disciplinary and multi-cultural platform to explore reactions to the emerging data, debate key concepts and interpret women’s experiences in the context of macro-level structural factors such as Kenyan politics and the socio-economic and cultural environment. These sessions were seminal in identifying themes of importance and topics that needed more probing, thus improving subsequent data collection. The scripts and transcripts were comprehensively read and were followed by a series of collaborative analytic working group meetings during which the team (PS, TB, RKabuti, EN, JK, JS) identified patterns emerging and ideas of interest. The scripts and transcripts were divided among four (PS, TB, RKabuti, EN) researchers and an inductive, data-driven process led to the production of initial codes, which were collated into themes and sub-themes. Regular meetings during this process provided a platform to compare and explain themes generated by each researcher. Disagreements were resolved through discussion of the emergence and relevance of themes. A codebook was then developed, containing the finalised themes as codes and defining them. The codebook developed through this process was formalised by repeatedly testing its comprehensiveness and validity by test-coding individual transcripts and comparing them for consistency between researchers until no new themes were emerging. A reflexive process helped to identify and record macro-level deductive structural factors such as political-economic context (poverty, education) and social-cultural context (gender roles, patriarchal society) that encompassed codes and themes. The data were coded by the four members of the research team (PS, TB, RKabuti, EN) in NVivo V.12. This study used the syndemic theory as an interpretive lens to explore family and gender dynamics, sexual and reproductive health, familial and intimate partner violence (IPV), education, livelihood and income.

Patient and public involvement

A community advisory group formed of sex workers, peer educators and other key stakeholders was convened prior to the start of the Maisha Fiti study. The group provided outreach and sensitisation and informed the study design, the interpretation of results and the dissemination of the results back to the community.

Results

Sociodemographics

For the Maisha Fiti main study, 1200 women were randomly selected to participate, with 1003 out of 1039 eligible women (response rate: 96%) recruited into the study. A total of 48 FSWs were interviewed for this qualitative methods study. The mean age of the participants in this qualitative study was 30 years, ranging from 18 to 44 years old. All study participants had received at least some formal education, with 35% having completed primary school, and 23% having completed secondary school. The mean age of sexual debut was 15.5 years, with 37% stating that it was not consensual. Most women (77%) had ever been married or co-habited with a partner. Only three of the women had never been pregnant, and three-quarters (71%) had had at least one child prior to starting sex work. The mean age of entry into sex work was 20.7 years, with the youngest being 13 years old and the oldest 29 years old. The characteristics of the participants are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographics of study participants

| N=48 | |

| Age, years | |

| Mean age (range) | 30 (18–44) |

| 18–24 | 15 (31%) |

| 25–34 | 19 (40%) |

| 35+ | 14 (29%) |

| Upbringing | |

| Rural | 24 (50%) |

| With ≥1 parent or related caregivers | 43 (90%) |

| In children’s home | 1 (2%) |

| Education level | |

| Some primary | 2 (4%) |

| Completed primary | 17 (35%) |

| Some secondary | 15 (31%) |

| Completed secondary | 11 (23%) |

| Higher education | 3 (6%) |

| Age at sexual debut | |

| Mean age (range) | 15.5 (2–20) |

| Consensual | 30 (63%) |

| Tricked, pressured or forced into having sex | 18 (38%) |

| Marital status | |

| Ever married/co-habited with sexual partner | 37 (77%) |

| Age at first marriage | |

| Mean age (range) | 19.6 (14–34) |

| ≤15 years old | 4 (11%) |

| 16–17 | 11 (30%) |

| 18+ | 22 (59%) |

| Current marital status | |

| Single | 16 (33%) |

| Married or cohabiting | 4 (8%) |

| Separated, divorced or widowed | 28 (58%) |

| Pregnancy | |

| Ever been pregnant | 45 (94%) |

| Age at first pregnancy | |

| Mean age (range) | 18.2 (9–24) |

| <18 years old | 17 (38%) |

| 18+ | 25 (56%) |

| Missing | 3 (7%) |

| Number of live children | |

| None | 4 (9%) |

| 1–2 | 31 (69%) |

| 3+ | 10 (22%) |

| Children born prior to entry into sex work | |

| Yes | 32 (71%) |

| No | 10 (22%) |

| Missing | 3 (7%) |

| Age when first sold sex | |

| Mean (range) | 20.7 (13–29) |

| <18 | 8 (17%) |

| 18–24 | 30 (63%) |

| 25+ | 10 (21%) |

| Age when regularly started selling sex | |

| Mean age (range) | 22.6 (15–33) |

| <18 | 6 (13%) |

| 18–24 | 26 (54%) |

| 25+ | 16 (33%) |

| Dependents | |

| Has dependents within household | 39 (81%) |

| Has dependents outside household | 30 (63%) |

Experiences in childhood

Financial hardship and incomplete education were described as being key factors of women’s early lives, with the majority not completing their primary education due to lack of school fees. Some women explained that as finances were limited, their brothers were given priority in terms of schooling. Participants described feeling neglected and having to look after the household while they were young. Most grew up in single parent families, and adults were often absent while trying to earn a living and providing for the family. Some women also explained that they felt they were a burden on the family.

I dropped (out of school) because I didn’t have fees. …We were poor, there was so much poverty in my home…. For mum it was a problem getting food. So I thought that there is no need of stressing my mum…I decided let me get out and go to search (for a job).

– IDI 26 (30 years old)

Women explained that witnessing and experiencing violence at home were common occurrences. Some participants described how their fathers, while intoxicated, frequently resorted to verbal and physical violence towards their mothers or them and their siblings. Girls experienced physical violence mostly from family members, and in some instances, teachers. Some women also described experiencing sexual violence in their formative years by perpetrators including neighbours, acquaintances and older friends, and with sexual violations occurring from a very young age.

… I went to stay with my sister and one day she came with a man who was drunk and that man sexually harassed me and he raped me when I was nine years old.

– IDI 1 (27 years old)

Women described how a lack of finances directly or indirectly affected their education, and together with childhood violence, influenced the course of their lives.

Experiences during adolescence/young adulthood

Most women recalled that they first had sexual intercourse as adolescents while still enrolled in school. This first time was often with their boyfriends and while many described it as being consensual, they also explained that they felt pressurised by peers who were sexually active to also have sexual intercourse. Some women described how lack of knowledge of or access to contraception led to becoming pregnant while in their teenage years, resulting in school dropout. Almost all the women who had been unable to complete their education attributed it to a lack of finances or pregnancy and described how they often did not receive support from their families and that they were expected to live as adults. Pregnancy increased this expectation. Many who left school described getting married (usually in a customary ceremony) or cohabiting. Most women explained how these early intimate relationships were difficult.

I started having sex very early…thirteen years. When in class seven [aged 15] I was already pregnant. I did not finish [school] that is where my life changed. I was chased away by mum and told to go and look for the one who gave me that pregnancy. I went and found that, that person was a womanizer, a man of pleasure. He would beat me, he would [literally] step on my head.

– IDI 40 (36 years old)

Some women also described experiencing sexual violence in their early relationships, with partners seeing sex as their right and women having no control over this. Almost all the women who had experienced physical or sexual violence in childhood also reported experiencing IPV, sometimes in front of their children, with many describing extreme forms of violence from multiple relationships. Partners were also emotionally and verbally abusive to women, creating an environment of low self-confidence, dependence and fear in which the women struggled to protect their children.

…I moved in with this man but he was not a peaceful man he was violent…He loved fighting and verbal abuse, lots of insults…This was very bad that as we continued it reached a point when my girl used to get very scared anytime he would come back home…my girl would perceive that he will start fighting as usual and it was very scary for her…

– IDI 7 (29 years old)

Many women did not have enough money either from their earnings or financial support from their partners for household expenses and to support their children. When women earned their own income when they were co-habiting, they often lacked full control over the spending as their partner controlled the money.

When you ask your husband [for] money for food he does not give you. I started brewing with [my mother-in-law] the chang’aa brew. Now the money I would get [from selling], my husband would take…and go to enjoy and to give to girls.

– IDI 22 (42 years old)

These difficult circumstances meant that most early relationships did not last as women found it necessary to leave the situation to support themselves and their children.

Entry into sex work

Women who left their early relationships often took their children with them to their new home, although a few women left their children in the care of their mothers or grandmothers. Those who lived in rural areas moved to Nairobi in the hope of better job prospects, but most did not have the required qualifications needed for formal jobs. They reported trying multiple ways to earn an income such as working in a hair salon or selling vegetables but they did not earn enough to provide for themselves and their dependents, especially as most women had at least one child.

Most women mentioned that they saw peers in their neighbourhood who seemed to be better off than them. When they asked them how they seemed to be earning more money, they were offered the chance to accompany them either to bars or to other locations where commercial sex was available.

I used to clean bedsheets in a lodging…[then] I started selling chips…Sometimes the business was good, sometimes it wasn’t so I spoke with a certain lady…. I explained to her that business was bad…I was short on rent and sometimes I didn’t have enough money to buy cooking oil for the chips…She told me that she did sex work. I didn’t like the idea but I decided to give it a shot. There was nothing else I could have done …So I started sex work and have been doing it since.

– IDI 15 (27 years old)

Most of the participants described that the biggest incentive for entering sex work was that they could bring home a lump sum of money when needed urgently. Lacking education certificates and stable employment as well as having multiple dependents and the inability to rely on family members or intimate partners meant that for almost all women, financial desperation precipitated their entry into sex work. Women’s views of sex work varied with most describing their entry into sex work as not being forced, but many women described feeling scared, nervous and stressed by the work. Some also described feelings of disgust at having sex with multiple strangers as well as facing stigma and discrimination from members of the public who knew of their profession. Nonetheless, most women reported persevering with it as they were able to support their dependents by paying school fees, rent, medical fees, and being able to afford regular meals.

It is work. […] many women in this road, on the streets; the girls who do sex work and prostitution, most of them…if given chances to do another thing, you would never see them on the streets. But there are some who do it for fun and there are some who do it because of that pain. As in you have gone through a lot of pain and you don’t want your baby to go through the same. So you find that you want to bring up your children differently from the way you were brought up. But most of them do say that God when you get me out of here, I will never go back to this work. Because it is not a good job, it is a very dirty job, you go through a lot, you meet people who misuse you, that’s it.

– IDI 23 (41 years old)

Two younger women described that they had not come out of a difficult relationship and had no children but they did have other dependents, and sex work provided a means of supporting them. One woman reported that she had completed her education and was currently attending university. She chose to enter sex work as an adolescent for some additional income with which she could buy non-essential items. However, this case was unusual.

Most women described feeling that although the work itself was not ideal, it provided them with some freedom from depending on others and being able to control their actions regarding clients, fees and working hours. It was also a means of providing for their dependents and was a possible route out of poverty.

Discussion

The syndemic theory can be used as a lens to investigate how the overall impact of co-occurring factors in childhood and adolescence contribute to entry into sex work and its related risks.45 It offers an innovative perspective on how macro events and complex social processes can result in a population being structurally disadvantaged, leading to vulnerabilities beyond individual control. Criteria for a syndemic include ‘two or more diseases or health conditions acting synergistically to increase health burden in a population, and the contextual and social factors creating the conditions for synergistic interaction’.46 47 Among this population, we found that childhood violence, poverty and incomplete education were structural syndemic co-factors that together with social factors such as teenage pregnancy, early marriage, IPV and relationship breakdown shaped the lives of women who entered into sex work and their subsequent high-risk sexual behaviours. Figure 1 summarises the conceptual framework that was developed from the data to describe the syndemic factors that coalesced to influence women’s journeys into sex work. We found that these syndemic co-factors created pathways between adverse childhood experiences, early intimate relationships and subsequent entry into sex work.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for exploring syndemic co-factors shaping the early lives of women who enter into sex work.

Girls in SSA face high levels of gender inequality in education with lower school enrolment and completion compared with boys.48 Despite primary and secondary education in Kenya being free, the related costs of attending school can be a barrier to school completion.49 Among women who subsequently enter sex work, 75% do not complete secondary education compared with around 60% of their female counterparts in the general population.18 50 The descriptions of physical and sexual violence experienced in childhood in this study add to the literature reporting high levels of childhood violence among FSWs globally.11 15 17 50 FSWs experience more childhood neglect, physical and sexual abuse than women in the general population,20 and studies from Soweto (South Africa) and Mombasa (Kenya) have reported that almost half of the FSWs in their populations experienced physical and sexual violence in childhood.17 50 Studies have shown that experiencing violence in childhood has a significant impact on educational outcomes, including school dropout.51 52 In this study, the syndemic co-factors of poverty, incomplete education and violence in childhood created two pathways, one where many girls who left school due to poverty got married in their adolescence and subsequently had a child, and the other where girls became pregnant while still in school and subsequently dropped out. Pregnancy was also reported as one of the main reasons for incomplete education and contributing to entry into sex work in a study with a similar participant demographic in Kenya18 and in a number of other studies in SSA.16 22 24 50 Sexual and reproductive health education is not included in the Kenyan school curriculum, and thus sexually active adolescents often do not have knowledge of, or access to, contraception.53

The social and cultural norms of Kenyan society and a need for financial provision meant that women who did not complete their education were married during their adolescence, usually in a customary or religious ceremony.54 Research shows that almost a third of adolescent girls and young women in low- and middle-income countries experience IPV,55 and experience of childhood abuse is significantly related to IPV victimisation,56 57 findings that were consistent with this study. These challenges of early marriage and violence often led to marriage breakdown for women in this study, which is a very common event reported by FSWs in SSA.22 The syndemic co-factors of pregnancy, early marriage, IPV and marriage breakdown created further pathways leading to women being financially insecure. Studies from Kenya and Ethiopia report that most women have at least one child prior to entering sex work, and some also have other dependants such as their parents or other family members.25 27 A need for economic survival and to financially support their dependents is the main proximal event that propels women into initiating sex work.3 16 17 22 23 58–60 A lack of labour skills and/or formal education completion certificates and patriarchal sociocultural norms exacerbated the situation of women in this study, leaving them with insufficient money to care for themselves and their dependents. Many women in this study had experienced violence in their childhood and intimate relationships, and the lack of alternatives meant that they had to face the possibility of future violence from clients. However, sex work enables women to have financial independence. In a situation of gender inequity and lack of employment, this creates a sense of empowerment meaning they can provide for themselves and their dependents on their terms. It is worth noting that consistent with the literature, although most FSWs in this study see it as a ‘last resort’, there are some women who see it as an opportunity to exercise their agency, being independent and self-reliant.16 22

This study provides insight into the pathways taken by girls that lead to sex work entry. These data have not emerged from previous quantitative research in SSA, and qualitative studies have tended to focus on the risks and consequences of sex work rather than vulnerabilities to initiation. However, this study has some limitations. These results will not be representative of all FSWs in Nairobi County, as the sampling methodology excluded FSWs who were not registered at a SWOP clinic and were potentially more vulnerable. Most participants in the study were older and had children prior to entering into sex work. The circumstances faced by younger women without dependents may be different and thus may represent different pathways into sex work. To address this, a second round of recruiting was carried out to address the under-representation of young women from the first round. Women were asked to describe events from their early lives, resulting in a potential for recall bias. Experiences of violence in childhood and intimate relationships may also have been under-reported due to normalisation of violence and a lack of behaviourally specific questions. The experiences described by women may not be causal in terms of the risks experienced by sex workers. The results of the study may have been influenced by social desirability bias, with the participants providing information based on what they felt the interviewers were seeking or what was socially sanctioned.

Conclusion

The results of this study have important implications for future interventions and practice. The pathways followed by women who enter into sex work highlight a range of structural and social syndemic co-factors that create vulnerabilities at pivotal moments that need to be addressed in order to support women. Policy changes should be considered to include sexual and reproductive health education in the national secondary school curriculum. Structural interventions to make contraceptive services available free of charge to minors should be considered, as should social care (through the cash transfer programme) covering the extra costs of education (such as school uniforms) to those most in need. Interventions are also needed to tackle domestic violence and to support young mothers by increasing their livelihood options.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all women who participated in this study. They also thank all the Maisha Fiti study champions (Demtilla Gwala, Daisy Oside, Ruth Kamene, Agnes Watata, Agnes Atieno, Faith Njau, Elizabeth Njeri, Evelyn Orobi & Ibrahim Lwingi) for their educational outreach and community engagement.

Footnotes

Contributors: TB and JK conceptualised the Maisha Fiti study. TB was principal investigator and acquired funding, and JK, JS, HAW and RKaul were co-investigators. RKabuti, ZJ and JK were responsible for study management. RKabuti, JL, MK, HB, ZJ, EN and the Maisha Fiti Study Champions were involved in investigation and validation of the study. PS, TB, RKabuti, JL, MK, HB, ZJ, JK, JS and EN formed the qualitative research team. PS, TB, RKabuti and EN carried out the qualitative data analysis. PS, TB, RKabuti, JS, JK and EN interpreted the results. PS prepared the first draft of the manuscript. PS, TB, NK, GM, KD, MG and JS were involved in reviewing and editing the writing and supervising. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. JK and JS are joint last authors. PS is responsible for the overall content as the guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC), the UK Department of International Development (DFID) (MR/R023182/1) and the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission (KECS-2019-843). Funding bodies had no role in the design, data collection or analysis of the study. Funding bodies also had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. The datasets generated from the Maisha Fiti study and analysed for the current study are currently not publicly available as the study has only recently been completed. However, from June 2023 (2 years after study completion), the datasets will be available from the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Institutional ethics approval for this study was obtained from Kenyatta National Hospital and University of Nairobi Research Ethics Committee (KNH ERC P778/11/2018), London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: 16229), and University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (Approval number: 37046). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Stoebenau K, Winograd L, Holmes A. Transactional sex and HIV risk: from analysis to action. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and STRIVE; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deering KN, Amin A, Shoveller J, et al. A systematic review of the correlates of violence against sex workers. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e42–54. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scorgie F, Chersich MF, Ntaganira I, et al. Socio-demographic characteristics and behavioral risk factors of female sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Behav 2012;16:920–33. 10.1007/s10461-011-9985-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. Lancet 2015;385:55–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baleta A. Lives on the line: sex work in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2015;385:e1–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61049-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyons CE, Schwartz SR, Murray SM, et al. The role of sex work laws and stigmas in increasing HIV risks among sex workers. Nat Commun 2020;11:773. 10.1038/s41467-020-14593-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avison WR. Incorporating children’s lives into a life course perspective on stress and mental health. J Health Soc Behav 2010;51:361–75. 10.1177/0022146510386797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Currie J, Widom CS. Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well-being. Child Maltreat 2010;15:111–20. 10.1177/1077559509355316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hertzman C, Power C, Matthews S, et al. Using an interactive framework of society and lifecourse to explain self-rated health in early adulthood. Soc Sci Med 2001;53:1575–85. 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00437-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boullier M, Blair M. Adverse childhood experiences. Paediatrics and Child Health 2018;28:132–7. 10.1016/j.paed.2017.12.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer LA, Berg EC. A survival analysis of timing of entry into prostitution: the differential impact of race, educational level, and childhood/adolescent risk factors. Sociol Inq 2003;73:511–28. 10.1111/1475-682X.00069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. Sexual abuse as a precursor to prostitution and victimization among adolescent and adult homeless women. J Fam Issues 1991;12:361–79. 10.1177/019251391012003007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoltz J-AM, Shannon K, Kerr T, et al. Associations between childhood maltreatment and sex work in a cohort of drug-using youth. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:1214–21. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson HW, Widom CS. The role of youth problem behaviors in the path from child abuse and neglect to prostitution: a prospective examination. J Res Adolesc 2010;20:210–36. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00624.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldenberg SM, Silverman JG, Engstrom D, et al. Exploring the context of trafficking and adolescent sex industry involvement in Tijuana, Mexico: consequences for HIV risk and prevention. Violence Against Women 2015;21:478–99. 10.1177/1077801215569079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mbonye M, Nalukenge W, Nakamanya S, et al. Gender inequity in the lives of women involved in sex work in Kampala, Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc 2012;15 Suppl 1:1–9. doi:17365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parcesepe AM, L’Engle KL, Martin SL, et al. Early sex work initiation and violence against female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. J Urban Health 2016;93:1010–26. 10.1007/s11524-016-0073-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ngugi EN, Benoit C, Hallgrimsdottir H, et al. Family kinship patterns and female sex work in the informal Urban settlement of Kibera, Nairobi, Kenya. Hum Ecol Interdiscip J 2012;40:397–403. 10.1007/s10745-012-9478-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.UNESCO Institute for Statistics . Primary education, pupils (% female) - sub-Saharan Africa. 2020. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.PRM.ENRL.FE.ZS?end=2010&locations=ZG&start=2007 [Accessed 04 Mar 2022].

- 20.McCarthy B, Benoit C, Jansson M. Sex work: a comparative study. Arch Sex Behav 2014;43:1379–90. 10.1007/s10508-014-0281-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gichane MW, Moracco KE, Pettifor AE, et al. Socioeconomic predictors of transactional sex in a cohort of adolescent girls and young women in Malawi: a longitudinal analysis. AIDS Behav 2020;24:3376–84. 10.1007/s10461-020-02910-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gysels M, Pool R, Nnalusiba B. Women who sell sex in a Ugandan trading town: life histories, survival strategies and risk. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:179–92. 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00027-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saggurti N, Verma RK, Halli SS, et al. Motivations for entry into sex work and HIV risk among mobile female sex workers in India. J Biosoc Sci 2011;43:535–54. 10.1017/S0021932011000277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agha S, Chulu Nchima M. Life-circumstances, working conditions and HIV risk among street and nightclub-based sex workers in Lusaka, Zambia. Cult Health Sex 2004;6:283–99. 10.1080/13691050410001680474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elmore-Meegan M, Conroy RM, Agala CB. Sex workers in Kenya, numbers of clients and associated risks: an exploratory survey. Reprod Health Matters 2004;12:50–7. 10.1016/s0968-8080(04)23125-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedro S, Luis Fernando M. Angola (2008): TRaC study evaluating condom use among commercial sex workers in luanda province. Second round. V3 ed. Harvard Dataverse, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tekola B. Negotiating social space: sex-workers and the social context of sex work in Addis Ababa; 2005.

- 28.Dugas M, Bédard E, Kpatchavi AC, et al. Structural determinants of health: a qualitative study on female sex workers in Benin. AIDS Care 2019;31:1471–5. 10.1080/09540121.2019.1595515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gysels M, Pool R, Bwanika K. Truck drivers, middlemen and commercial sex workers: AIDS and the mediation of sex in South West Uganda. AIDS Care 2001;13:373–85. 10.1080/09540120120044026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Homaifar N, Wasik SZ. Interviews with Senegalese commercial sex trade workers and implications for social programming. Health Care Women Int 2005;26:118–33. 10.1080/07399330590905576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voeten HACM, Egesah OB, Varkevisser CM, et al. Female sex workers and unsafe sex in urban and rural Nyanza, Kenya: regular partners may contribute more to HIV transmission than clients. Trop Med Int Health 2007;12:174–82. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01776.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization . Preventing HIV among sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review. Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musyoki H, Bhattacharjee P, Blanchard AK, et al. Changes in HIV prevention programme outcomes among key populations in Kenya: data from periodic surveys. PLoS One 2018;13:e0203784. 10.1371/journal.pone.0203784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hyun M-S, Okolo W-S, Munene A-GE. USAID/kenya gender analysis report; 2020.

- 35.Gender WaCSDA . Country gender note for kenya in the context of the bank CSP 2014-2018 mid term review: is gender a number one poverty issue? African Development Bank Group, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimani EN, Kombo DK. Gender and poverty reduction: a Kenyan context. Educ Res Rev 2010;5:024–30. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhattacharjee P, Ma H, Musyoki H, et al. Prevalence and patterns of gender-based violence across adolescent girls and young women in Mombasa, Kenya. BMC Womens Health 2020;20:229. 10.1186/s12905-020-01081-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.FIDA Kenya . Documenting human rights violation of sex workers in Kenya: a study conducted in Nairobi, Kisumu, Busia, Nanyuki, Mombasa and Malindi. Nairobi, Kenya: Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA) Kenya, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics . 2019 Kenya population and housing census. Nairobi, Kenya: Government of Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 40.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP) . Key population mapping and size estimation in selected counties in Kenya: phase 1 key findings. Nairobi, Kenya: Ministry of Health, Government of Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimani J, McKinnon LR, Wachihi C, et al. Enumeration of sex workers in the central business district of Nairobi, Kenya. PLoS One 2013;8:e54354. 10.1371/journal.pone.0054354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beksinska A, Jama Z, Kabuti R, et al. Prevalence and correlates of common mental health problems and recent suicidal thoughts and behaviours among female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21:503. 10.1186/s12888-021-03515-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kielmann K, Cataldo F, Seeley J. Introduction to qualitative research methodology: a training manual. United Kingdom: Department for International Development (DfID), 2012: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singer M. Introduction to syndemics: a critical systems approach to public and community health. John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B. Whither syndemics?: Trends in syndemics research, a review 2015-2019. Glob Public Health 2020;15:943–55. 10.1080/17441692.2020.1724317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, et al. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet 2017;389:941–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30003-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.UNICEF . Gender and education. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maiyo J, Bawane J. Education and poverty, relationship and concerns. A case for Kenya; 2011.

- 50.Coetzee J, Gray GE, Jewkes R. Prevalence and patterns of victimization and polyvictimization among female sex workers in Soweto, a South African township: a cross-sectional, respondent-driven sampling study. Glob Health Action 2017;10:1403815. 10.1080/16549716.2017.1403815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fry D, Fang X, Elliott S, et al. The relationships between violence in childhood and educational outcomes: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl 2018;75:6–28. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pieterse D. Childhood maltreatment and educational outcomes: evidence from South Africa. Health Econ 2015;24:876–94. 10.1002/hec.3065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agbemenu K, Schlenk EA. An integrative review of comprehensive sex education for adolescent girls in Kenya. J Nurs Scholarsh 2011;43:54–63. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuria GK. The African or customary marriage in Kenyan law today. In: Transformations of African marriage. Routledge, 2018: 283–306. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Decker MR, Latimore AD, Yasutake S, et al. Gender-based violence against adolescent and young adult women in low- and middle-income countries. J Adolesc Health 2015;56:188–96. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li S, Zhao F, Yu G. Childhood maltreatment and intimate partner violence victimization: a meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl 2019;88:212–24. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richards TN, Tillyer MS, Wright EM. Intimate partner violence and the overlap of perpetration and victimization: considering the influence of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse in childhood. Child Abuse Negl 2017;67:240–8. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowen KJ, Dzuvichu B, Rungsung R, et al. Life circumstances of women entering sex work in Nagaland, India. Asia Pac J Public Health 2011;23:843–51. 10.1177/1010539509355190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hampanda KM. The social dynamics of selling sex in mombasa, Kenya: a qualitative study contextualizing high risk sexual behaviour. Afr J Reprod Health 2013;17:141–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McClarty LM, Bhattacharjee P, Blanchard JF, et al. Circumstances, experiences and processes surrounding women’s entry into sex work in India. Cult Health Sex 2014;16:149–63. 10.1080/13691058.2013.845692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-068886supp001.pdf (87.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. The datasets generated from the Maisha Fiti study and analysed for the current study are currently not publicly available as the study has only recently been completed. However, from June 2023 (2 years after study completion), the datasets will be available from the corresponding author.