Abstract

Radiation-induced esophageal injury remains a limitation for the process of radiotherapy for lung and esophageal cancer patients. Esophageal epithelial cells are extremely sensitive to irradiation, nevertheless, factors involved in the radiosensitivity of esophageal epithelial cells are still unknown. Terminal uridyl transferase 4 (TUT4) could modify the sequence of miRNAs, which affect their regulation on miRNA targets and function. In this study, we used transcriptome sequencing technology to identify mRNAs that were differentially expressed before and after radiotherapy in esophageal epithelial cells. We further explored the mRNA expression profiles between wild-type and TUT4 knockout esophageal epithelial cells. Volcano and heatmap plots unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis were performed to classify the samples. Enrichment analysis on Gene Ontology functional annotations and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways was performed. We annotated differential genes from metabolism, genetic information processing, environmental information processing, cellular processes, and organismal systems human diseases. The aberrantly expressed genes are significantly enriched in irradiation-related biological processes, such as DNA replication, ferroptosis, and cell cycle. Moreover, we explored the distribution of transcription factor family and its target genes in differential genes. These mRNAs might serve as therapeutic targets in TUT4-related radiation-induced esophageal injury.

Keywords: esophageal epithelial, radiosensitivity, terminal uridyl transferase 4, radiation-induced esophageal injury

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (ESCA) is one of the most common cancers that results in high mortality rate worldwide. Some therapeutic treatments, such as surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, have been verified to somewhat improve the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer.1 Radiation therapy is one of the main treatment methods for esophageal cancer. During radiotherapy, radiation-induced esophageal injury may cause severe symptoms, such as severe chest pain, fever, cough, difficulty breathing, vomiting, and hematemesis. Esophageal tissue damage during radiotherapy for esophageal cancer is a vital reason for the interruption and failure of radiotherapy.2,3 Esophageal epithelial cells are extremely sensitive to ionizing radiation, and different doses of ionizing radiation may cause different degrees of damage to the esophageal epithelium.4 However, the factors affecting the radiosensitivity of esophageal epithelial cells are still poorly understood, and only a few studies have reported amifostine,5 tea polyphenols,6 and soy isoflavones.7 Radiation-induced esophageal injury still lacks effective prevention and treatment targets and means, which seriously affects the smooth progress of radiotherapy and the quality of life of patients.

Terminal uridyl transferase 4 (TUT4) is an RNA terminal uracil transferase, which can modify the terminal uracil of specific mature miRNA without template, and change the 3′-terminal sequence of miRNA, thereby affecting the expression level and function of miRNA on target genes. Terminal uridyl transferase 4 is essential for both oocyte maturation and fertility. Through 3′ terminal uridylation of mRNA, sculpts, with TUT7, the maternal transcriptome by eliminating transcripts during oocyte growth. Involved in microRNA (miRNA)-induced gene silencing through uridylation of deadenylated miRNA targets. Also, functions as an integral regulator of microRNA biogenesis using 3 different uridylation mechanisms.8 Acts as a suppressor of miRNA biogenesis by mediating the terminal uridylation of some miRNA precursors, including that of let-7 (pre-let-7), miR107, miR-143, and miR-200c. Uridylated miRNAs are not processed by Dicer and undergo degradation. Degradation of pre-let-7 contributes to the maintenance of embryonic stem (ES) cell pluripotency (By similarity). It also catalyzes the 3′ uridylation of miR-26A, a miRNA that targets IL6 transcript. This abrogates the silencing of IL6 transcript, hence promoting cytokine expression.9 For group II pre-miRNAs, TUT7 and TUT4 through mono-uridylation to promot the miRNA biogenesis in the absence of LIN28A.8 Adds oligo-U tails to truncated pre-miRNAS with a 5′ overhang which may promote rapid degradation of non-functional pre-miRNA species.8 May also suppress Toll-like receptor-induced NF-kappa-B activation via binding to T2BP.10 However, TUT4 does not play a role in replication-dependent histone mRNA degradation.11 TUT4 and TUT7 restrict retrotransposition of long interspersed element-1 (LINE-1) in cooperation with MOV10 counteracting the RNA chaperonne activity of L1RE1. TUT7 uridylates LINE-1 mRNAs in the cytoplasm which inhibits initiation of reverse transcription once in the nucleus, whereas uridylation by TUT4 destabilizes mRNAs in cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein granules.12

The DNA damage response (DDR) and the mechanism of DNA repair tend to quickly start within the initial stage (48 h) after irradiation.13 It is reported that TUT4/7-mediated uridylation plays a key physiological role in maintaining genome stability.12 This revealed the biological roles of TUT4 in maintaining genome stability during DNA repair after radiation. Moreover, in our preliminary study, we demonstrated that TUT4 is closely associated with radiation-induced esophageal injury and that TUT4 affected the uridylation of miR-132/212.14,15 Our previous study found that the expression of uracil transferase TUT4 was higher in esophageal epithelial cells. Knockdown of TUT4 expression in human esophageal epithelial cells significantly increased the radiosensitivity of the cells. The esophagus injury of TUT4-knockout mice was more severe than that of wild-type mice after irradiation, manifesting as capillary congestion in esophageal tissue, thinning of squamous epithelial cells, and increased infiltration of inflammatory cells, which was consistent with the reports in the literature.7,16

In this paper, we set about to investigate the mechanism of radiation-induced esophageal injury, and uncover the functions of TUT4 in radiotherapy. The transcriptome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis were conducted to explore the function of differentially expressed mRNAs. A set of key protein-coding genes were identified. Gene Ontology (GO) functional annotations and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways were subsequently identified via gene set enrichment analysis. Moreover, we show the KEGG network path diagram in detail. Finally, we explored the distribution of transcription factor family target genes among differential genes.

Method

1. Cell Culture, Knockdown of TUT4, and Radiotherapy Regimen

The human esophageal epithelial cells (HEEC) were maintained in 1× Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 (RPMI-1640; Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and 1% penicillin streptomycin (Pen Strep; Gibco, Grand Island, NY) in a humidified atmosphere of 37°C and 5% CO2.

A set of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against TUT4 and a scrambled siRNA used as negative control were designed by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The specific small interfering RNA was performed using custom-made siRNA targeting the TUBB4A mRNA region (siTUT4 sense: GCTTCTGACCTTAATGATGATCTCGAG, siTUT4 antisense: ATCATCATTAAGGTCAGAAGCTTTTTT) and negative control (siNC sense: UUCUUCGAACGUGUCACGUTT, antisense: ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT) (GenePharma, China). Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well, and siRNAs were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at a final concentration of 100 nM according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A single dose of 6-Gy irradiation was administered to the HEEC esophageal cell at a dose rate of 2 Gy/min using 6-MeV x-ray irradiation (Clinac 2100EX; Varian Medical Systems, Inc, California). After 24h of a single dose of 6-Gy irradiation, cells were harvested for mRNA extraction.

2. RNA Isolation and Library Preparation

Total RNA was extracted using the Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA purity and quantification were evaluated using the NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). RNA integrity was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Then the libraries were constructed using TruSeq Stranded mRNA LT Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The transcriptome sequencing and analysis were conducted by OE Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

3. Quality Control and RNA Sequencing

The libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated. The HiSeq X Ten System is specifically designed for population-scale whole-genome sequencing. Each HiSeq X System can sequence the human genome at 30-fold or greater coverage. Raw data (raw reads) were processed using Trimmomatic.17 The reads containing ploy-N and the low quality reads were removed to obtain the clean reads. Then, the clean reads were mapped to the human genome (GRCh38) using HISAT2.18

4. Differential Expression Analysis

Fragments per kilobase million (FPKM)19 value of each gene was calculated using cufflinks,20 and the read counts of each gene were obtained by htseq-count.21 DEGs were identified using the DESeq R package functions estimateSizeFactors and nbinomTest. P value <.05 and absolute log2FoldChange >1 were set as the threshold for significantly differential expression. Hierarchical cluster analysis of DEGs was performed to explore genes expression pattern (Supplementary material).

5. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis

Gene Ontology enrichment and KEGG pathways enrichment analysis of DEGs were, respectively, performed using R based on the hypergeometric distribution. All the three types of GO functional annotations, including biological process (BP), cellular composition (CC), and molecular function (MF), were covered. The pathway diagram was derived from KEGG database.

6. Analysis of Transcription Factors and Their Target Genes

By comparing the distribution of transcription factors across all genes and differential genes, transcription factors with significant proportional differences can be found. The differential target genes corresponding to the differential transcription factors were identified, and the histogram of the target genes of the differential transcription factor family was drawn.

7. Statistical Analysis

The data from this study were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Difference between groups was assessed using a two-sided student t-test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression and Correlation of Samples

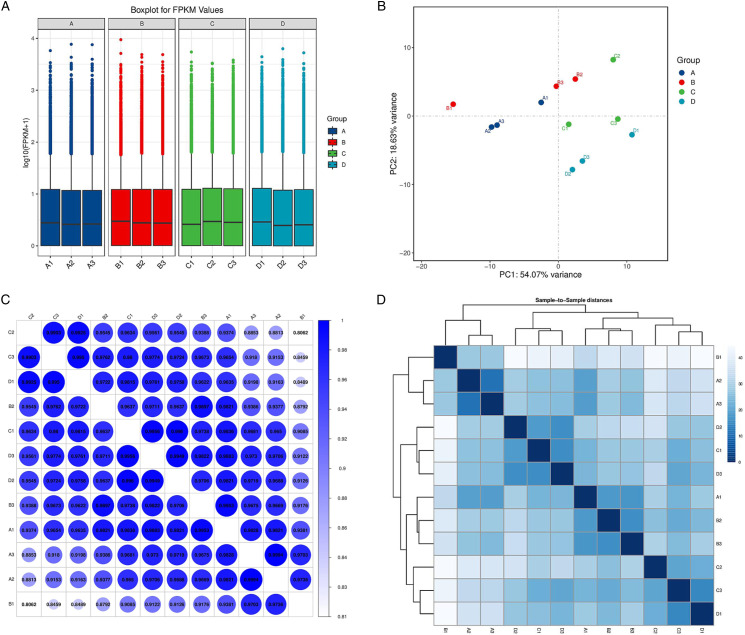

The box plot shows the distribution of expression data from all the samples. After normalization, the total gene expression was basically the same, indicating insignificant batch effects and system deviations (Figure 1A). Figure 1B shows the results of principal component analysis (PCA). Principal component analysis of the transcriptome profiles of four cluster patterns shows a difference in the transcriptome between different clusters. Different dots of duck blue, red, green, and light blue in the scatter diagram represent clusters A to D. The result of PCA indicated that the consensus cluster well differentiated cluster A, cluster B, cluster C, and cluster D. To further understand the relations among 12 samples, correlations among the mRNA expression of these genes were analyzed by Pearson correlation analysis. In the correlation analysis, there were strong correlations between samples within groups. In particular, sample A2 and sample A3 showed the strongest positive correlation (r = .9994) (Figure 1C). The cluster diagram of samples obtained according to gene expression is shown in Figure 1D.

Figure 1.

Gene expression level, principal component analysis, and correlations among samples. (A) A box plot shows the distribution of expression data from all the samples. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA). (C) The correlations among samples were analyzed by Pearson correlation. (D) The gene expression cluster diagram of samples. Group A: TUT4−/− nonirradiated group, Group B: TUT4 +/+ nonirradiation group, Group C: TUT4−/− irradiation group, Group D: TUT4 +/+ irradiation group.

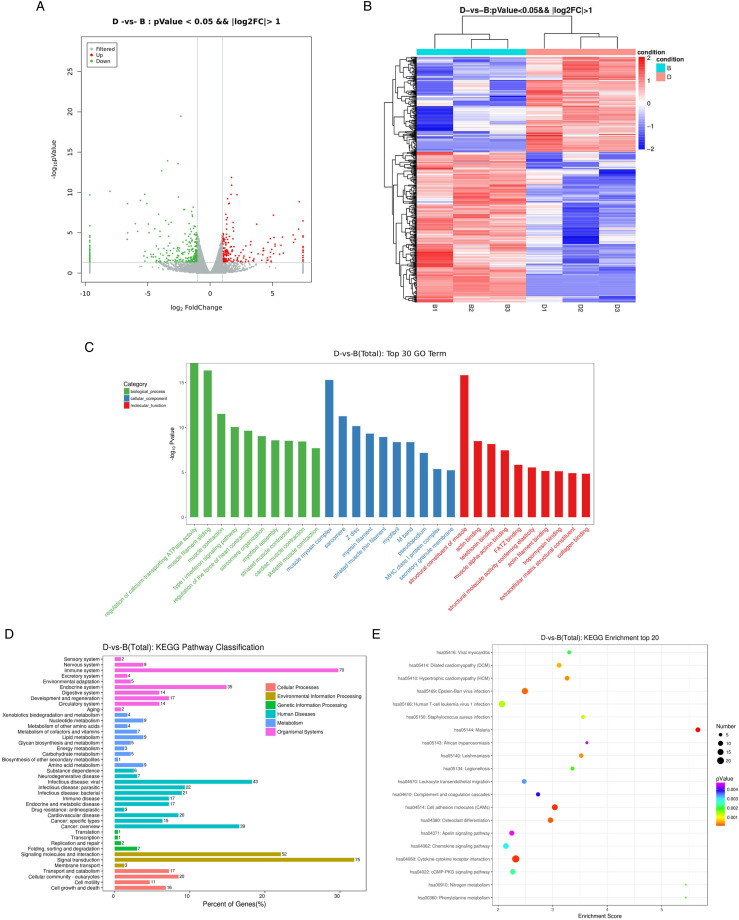

Differential Expression mRNAs in Irradiated HEEC Esophageal Cells

The volcano plot visualizes the differential expression mRNA of normal esophageal cells before and after irradiation (Figure 2A). The vertical lines correspond to log2 foldchange up or down, respectively, and the horizontal line represents a P-value of .05. The red and blue points in the plot represent the up-regulated and down-regulated mRNAs with statistical significance, separately. Compared to the control group, 201 up-regulated and 318 down-regulated mRNAs were detected in the radiotherapy group. Table 1 and Table 2 demonstrate the top 10 up-regulated and 10 down-regulated DEmRNAs between irradiated and nonirradiated HEEC esophageal cells.

Figure 2.

Expression profiles of radiotherapy-related DEGs and enrichment analysis. (A) Volcano map of DEG expression levels between the irradiated group (Group D) and nonirradiated group (Group B). (B) Heatmap hierarchical clustering analysis of DEGs in the irradiation group and nonirradiated group. (C) GO enrichment analysis of DEGs showed biological process (BP); cellular component (CC); molecular function (MF); (D) KEGG pathway classification of DEGs. (E) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs.

Table 1.

Top 10 up-regulated mRNAs in irradiated HEEC esophageal cells.

| mRNA | log2FoldChange | P-value | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBA7 | 1.713990661 | 1.40E-12 | Up |

| MT1E | 1.723564074 | 1.26E-11 | Up |

| MT1X | 1.675845229 | 1.75E-10 | Up |

| AIM2 | 2.151211262 | 1.93E-10 | Up |

| IFI6 | 1.398061092 | 5.99E-10 | Up |

| XIRP2 | 7.133867796 | 1.41E-09 | Up |

| RTP4 | 1.540888898 | 2.19E-09 | Up |

| PSMB9 | 1.491656816 | 2.49E-09 | Up |

| KRT6A | 1.258448111 | 5.10E-08 | Up |

| CA3 | 5.069808221 | 6.62E-08 | Up |

Table 2.

Top 10 down-regulated mRNAs in irradiated HEEC esophageal cells.

| mRNA | log2FoldChange | P-value | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FOS | −2.339084487 | 3.42E-20 | Down |

| DCN | −3.400242189 | 1.19E-14 | Down |

| WNT5A | −2.570702739 | 2.76E-14 | Down |

| MGP | −3.87628741 | 2.07E-13 | Down |

| HBA1 | −8.015307696 | 7.14E-11 | Down |

| AEBP1 | −5.230953841 | 1.67E-10 | Down |

| HBB | −9.632380982 | 2.00E-10 | Down |

| VIM | −2.530585106 | 3.71E-10 | Down |

| CNN1 | −5.577360766 | 9.83E-10 | Down |

| MFAP4 | −5.066010339 | 2.36E-09 | Down |

The heatmap of hierarchical clustering analysis showed that these differentially expressed genes (DEGs) could distinguish samples of irradiation group from the samples of nonirradiation group (Figure 2B).

GO and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Irradiated HEEC Esophageal Cells

To uncover the role of the differentially expressed genes in the irradiation of esophageal cells, GO enrichment analysis was carried out. As shown in Figure 2C, DEGs are significantly enriched in BP, such as regulation of calcium-transporting ATPase activity, muscle filament sliding, and muscle contraction. As for CC, these DEGs were significantly enriched in muscle myosin complex and sarcomere. For MF, they were significantly enriched in structural constituent of muscle and actin binding.

In further KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, organismal systems associated with DEGs include immune system and endocrine system. Human diseases include viral infectious disease and overview cancer. Environmental Information Processing include signal transduction, signaling molecules, and interaction.

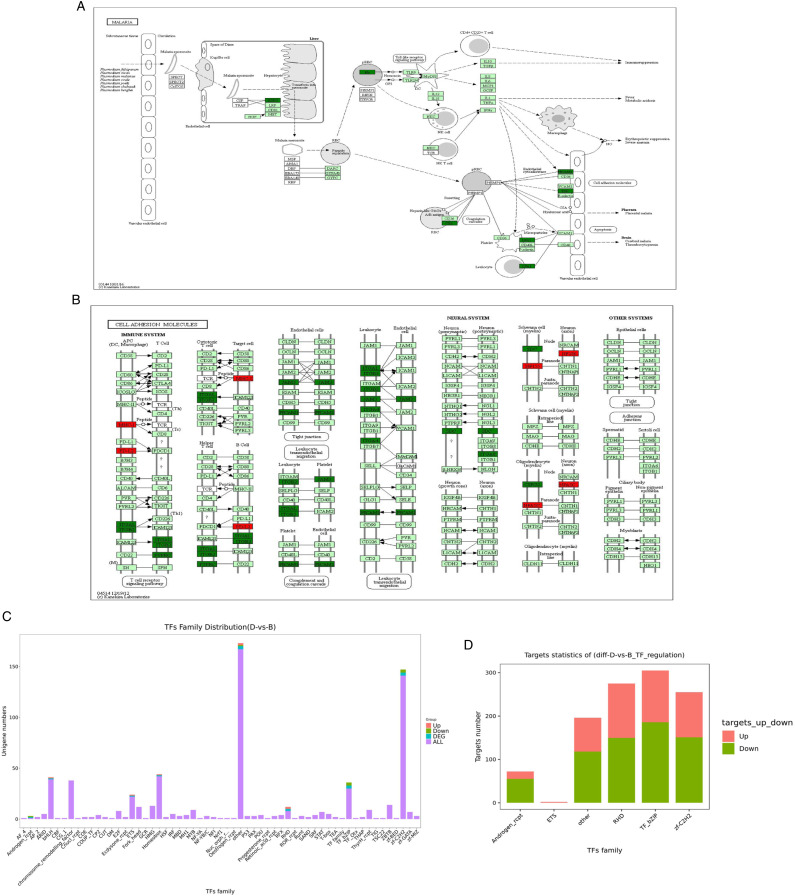

Furthermore, we observed that DEGs were significantly enriched in several related pathways, including malaria, cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction. The genes involved in the malaria pathway included CR1, THBS2, SDC2, HBB, HBA2, HBA1, ITGAL, PECAM1, and ITGB2 (Figure 3A). The genes involved in the CAMs pathway included PTPRC, NFASC, ITGA4, VCAN, HLA-F, HLA-A, HLA-B, and SDC2 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

KEGG pathway diagram, and statistics of transcription factors family and target genes. (A and B) Malaria and cell adhesion molecules pathway diagram. Red nodes are associated with up-regulated genes, and duck green nodes are associated with down-regulated genes. (C) Transcription factors distribution of DEGs. (D) Target genes statistics of DEGs.

Predictive Analysis of Transcription Factors and Their Target Genes

The distribution of transcription factor families mainly includes other, zf-C2H2, homeobox, bHLH, and TF bZIP (Figure 3C). According to the relationship between transcription factors and target genes, the corresponding differential target genes of differential transcription factors were extracted and the statistical map of target genes of differential transcription factor family was drawn. Results show that TF bZIP, RHD, and zf-C2H2 transcription factor families have more target genes (Figure 3D).

Effect of Irradiation on TUT4−/− HEEC Esophageal Cells

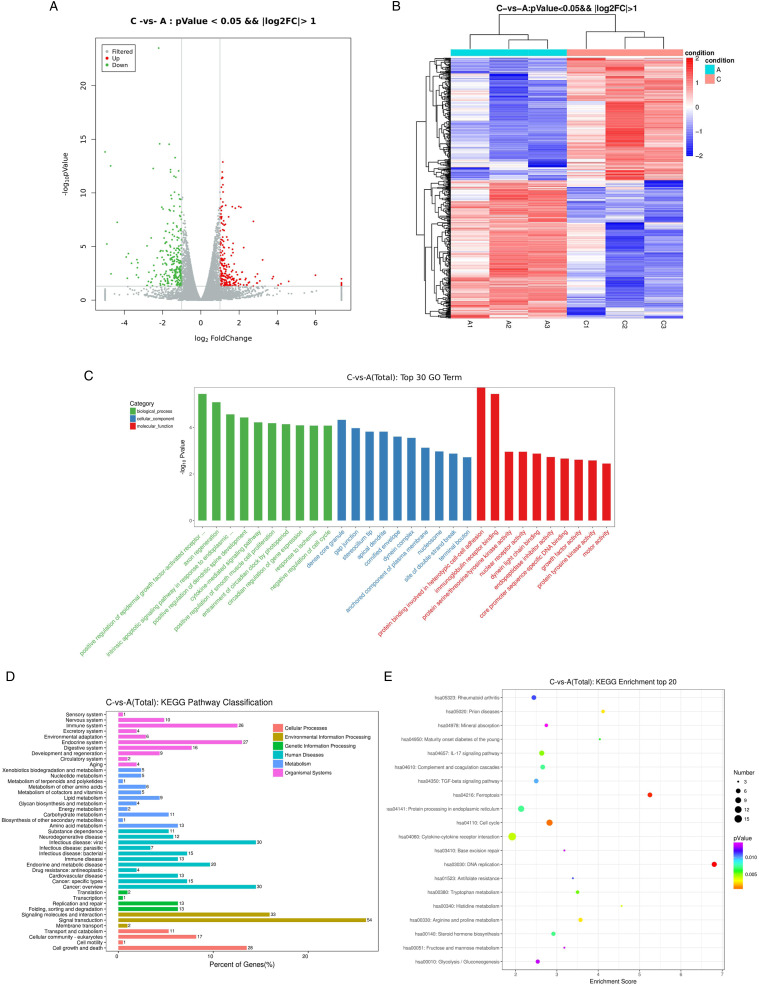

The differential expression analysis revealed 502 mRNAs that are differentially expressed between irradiated and nonirradiated esophageal cell samples. Among them, 236 mRNAs are up-regulated in the radiotherapy group, and 266 mRNAs are down-regulated. As is illustrated in Figure 4A and 4B, the differentially expressed mRNAs are visually displayed in the form of volcano map and heat map. Table 3 and Table 4 demonstrate the top 10 up-regulated and 10 down-regulated DEmRNAs between irradiated and nonirradiated TUT4−/− HEEC esophageal cells.

Figure 4.

Expression profiles of TUT4−/− radiotherapy-related DEGs and enrichment analysis. (A) Volcano map of DEG expression levels between the TUT4−/− irradiation group and TUT4−/− nonirradiated group. (B) Heatmap hierarchical clustering analysis of TUT4−/− DEGs in the irradiation group and nonirradiated group. (C) GO enrichment analysis of TUT4−/− DEGs showed biological process (BP); cellular component (CC); molecular function (MF); (D) KEGG pathway classification of DEGs. (E) KEGG enrichment analysis of TUT4−/− DEGs.

Table 3.

Top 10 up-regulated mRNAs in irradiated TUT4−/− HEEC esophageal cells.

| mRNA | log2FoldChange | P-value | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| KPNA2 | 1.147459201 | 1.30E-13 | Up |

| UBE2C | 1.119709013 | 1.11E-12 | Up |

| MCM2 | 1.120085033 | 3.49E-12 | Up |

| DDX39A | 1.141302376 | 3.79E-12 | Up |

| CCNB1 | 1.09286374 | 4.46E-12 | Up |

| RFC3 | 1.152633481 | 1.73E-11 | Up |

| ARL6IP1 | 1.073919344 | 2.96E-11 | Up |

| C1orf112 | 1.161226775 | 8.18E-11 | Up |

| NCAPH | 1.031550917 | 3.56E-10 | Up |

| TRAIP | 1.150884682 | 7.09E-10 | Up |

Table 4.

Top 10 down-regulated mRNAs in irradiated TUT4−/− HEEC esophageal cells.

| mRNA | log2FoldChange | P-value | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CXCL2 | −2.205246776 | 3.06E-24 | Down |

| WNT5A | −2.152456244 | 2.62E-15 | Down |

| LOC100130449 | −1.657783093 | 2.87E-15 | Down |

| HSPA6 | −5.006782752 | 1.50E-14 | Down |

| RHOB | −1.345015215 | 5.14E-14 | Down |

| HMOX1 | −4.717596122 | 3.00E-13 | Down |

| EGR1 | −2.490610992 | 5.27E-13 | Down |

| DBP | −1.586179323 | 6.74E-13 | Down |

| YPEL5 | −1.16225183 | 8.78E-13 | Down |

| DUSP1 | −1.585963919 | 1.13E-12 | Down |

As shown in Figure 4C, differentially expressed mRNAs were significantly enriched in positive regulation of epidermal growth factor-activated receptor activity, axon regeneration, and intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. As for CC, these DEGs were enriched in dense core granule, gap junction, and stereocilium tip. For MF, they were enriched in protein binding involved in heterotypic cell–cell adhesion, immunoglobulin receptor binding, and protein serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase activity.

Classifications of significantly enriched pathway are shown in Figure 4D. Organismal systems of DEGs include endocrine system and immune system. DEGs enrich in some metabolic process, such as, amino acid metabolism and carbohydrate metabolism. Related human diseases include cancer and viral infectious disease. Genetic information processing include folding, sorting, degradation, replication, and repair.

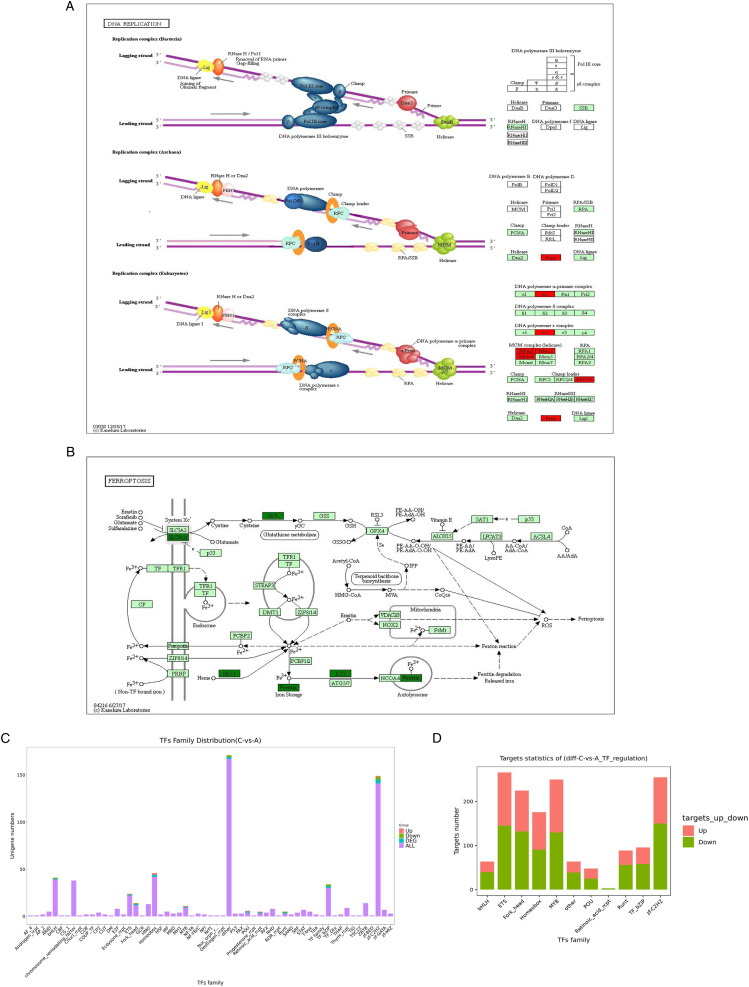

The TUT4−/− DEmRNAs were significantly involved in the processes of DNA replication, ferroptosis, and cell cycle. The genes involved in the DNA replication pathway included MCM2, MCM3, MCM4, FEN1, POLA2, RFC3, and POLE2 (Figure 5A). The genes involved in the ferroptosis pathway included GCLM, SLC7A11, GCLC, MAP1LC3B, FTL, and HMOX1 (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

KEGG pathway diagram, and statistics of transcription factors family and target genes between the TUT4−/− irradiation group and TUT4−/− nonirradiated group. (A and B) DNA replication and ferroptosis pathway diagram. (C) Transcription factors distribution of TUT4−/− DEGs. (D) Target genes statistics of TUT4−/− DEGs.

The distribution of transcription factor families about TUT4−/− DEmRNAs was similar to the results between the irradiation group and the nonirradiated group (Figure 5C). However, the corresponding differential target genes of differential transcription factors are shown in Figure 5D, indicating that ETS, zf-C2H2, and MYB transcription factor families have more target genes.

Discussion

Despite the remarkable advancement made in esophageal cancer therapeutic strategies, the long-term prognosis of esophageal cancer patients remains poor. Radiation therapy is one of the main treatment methods for esophageal cancer. However, there are limitations to understand the underlying mechanisms of radiation-induced esophageal injury. This study aimed to explore the function and significance of differentially expressed mRNAs in esophageal cells after irradiation. Using RNA-seq, we investigated radiation-induced transcriptome alterations in irradiated and nonirradiated esophageal cells. Firstly, we explored the effect of irradiation on HEEC esophageal cells, and conducted bioinformatics analysis to explore the function of differentially expressed mRNAs. A total of 201 up-regulated and 318 down-regulated mRNAs that are differentially expressed in radiotherapy group are identified. The functional and pathway annotations demonstrate that the aberrantly expressed genes participate in biological processes of regulation of calcium-transporting ATPase activity, muscle filament sliding, and muscle contraction. Also, cellular compositions and molecular functions are related to muscle myosin complex, sarcomere, and structural constituent of muscle.

Identification of molecular factors responsible for conferring radio-resistance and developing new strategies that increase sensitivity to radiation is warranted. We further constructed TUT4 knockout esophageal epithelial cells and explored the mRNA expression profiles in wild-type and TUT4 knockout esophageal epithelial cells. Also, GO functional annotations and KEGG pathways were subsequently identified via gene set enrichment analysis. TUT4−/− DEGs were significantly enriched in positive regulation of epidermal growth factor-activated receptor activity, axon regeneration, and intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. It is reported that esophageal cells that were exposed to IR show a heavy inflammatory response and slight oncogenicity. The above results have also been described in previous studies concerning irradiated non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells.22

The TUT4−/− DEmRNAs were significantly involved in the processes of DNA replication, ferroptosis, and cell cycle. Radiation exposure increases the levels of intracellular free radical species, followed by DNA strand breaks and subsequent dysfunction of the mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and other organelles.23,24 MCM2, MCM3, and MCM4 are related to the DNA replication pathway. It is reported that mini-chromosome maintenance proteins (MCM) is involved in the initiation of eukaryotic genome replication. The hexameric protein complex formed by MCM proteins is a key component of the pre-replication complex (pre_RC) and may be involved in the formation of replication forks and in the recruitment of other DNA replication related proteins.25-27

In our preliminary study, we demonstrated that TUT4 is closely associated with radiation-induced esophageal injury and that TUT4 affected the uridylation of miR-132/212.14,15 This study further illustrated the role of TUT4 in esophageal epithelial cell radiosensitivity and radiation-induced esophageal injury. Enrichment analysis results indicate that TUT4−/− DEmRNAs associated with DNA replication, ferroptosis, and cell cycle might contribute to radiation-induced esophageal injury. Complemented with our previous research, our data provided new clues for the understanding of the molecular mechanisms, and we believe this study would provide novel insights of the biological mechanism in radiation-induced esophageal injury.

Our findings demonstrated the differentially expressed genes in radiation-induced esophageal injury for the first time. DNA replication, ferroptosis, and cell cycle might be related to TUT4-related radiation-induced esophageal injury. Considering the vital role of mRNAs in radiation-related biological processes and pathways, we have also highlighted their role as therapeutic targets for the radiation-induced esophageal injury. Additional experiments will be required to address the significance of these findings, the binding characteristics of the identified mRNAs, and their biological function after exposure to radiation. A limitation of this study mainly lies in that the data we analyzed is obtained from transcriptome sequencing, although enrichment analysis has suggested several related pathways. There is still a lack of verification of wet-lab biochemical experiments. We intend to conduct in vitro or in vivo biological experiments to verify our results in future research.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82073339; 81773224), Scientific Projects of Xinjiang (SKL-HIDCA-2019-38).

ORCID iD

Jiaqi Zhang https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3580-9227

References

- 1.Wang N, Jia Y, Wang J, et al. Prognostic significance of lymph node ratio in esophageal cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(4):2335-2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephans KL, Djemil T, Diaconu C, et al. Esophageal dose tolerance to hypofractionated stereotactic body radiation therapy: Risk factors for late toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90(1):197-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Z, Xu J, Zhou T, et al. Risk factors of radiation-induced acute esophagitis in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with concomitant chemoradiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bar-Ad V, Leiby B, Witek M, et al. Treatment-related acute esophagitis for patients with locoregionally advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with involved-field radiotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37(5):433-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vujaskovic Z, Thrasher BA, Jackson IL, Brizel MB, Brizel DM. Radioprotective effects of amifostine on acute and chronic esophageal injury in rodents. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69(2):534-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao H, Xie P, Li X, et al. A prospective phase II trial of EGCG in treatment of acute radiation-induced esophagitis for stage III lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2015;114(3):351-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fountain MD, Abernathy LM, Lonardo F, et al. Radiation-induced esophagitis is mitigated by soy isoflavones. Front Oncol. 2015;5:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim B, Ha M, Loeff L, et al. TUT7 controls the fate of precursor microRNAs by using three different uridylation mechanisms. EMBO J. 2015;34(13):1801-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heo I, Joo C, Kim YK, et al. TUT4 in concert with Lin28 suppresses microRNA biogenesis through pre-microRNA uridylation. Cell. 2009;138(4):696-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minoda Y, Saeki K, Aki D, et al. A novel Zinc finger protein, ZCCHC11, interacts with TIFA and modulates TLR signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344(3):1023-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullen TE, Marzluff WF. Degradation of histone mRNA requires oligouridylation followed by decapping and simultaneous degradation of the mRNA both 5′ to 3′ and 3′ to 5′. Genes Dev. 2008;22(1):50-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warkocki Z, Krawczyk PS, Adamska D, Bijata K, Garcia-Perez JL, Dziembowski A. Uridylation by TUT4/7 Restricts Retrotransposition of Human LINE-1s. Cell. 2018;174(6):1537-1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Peng Z, Liu Q, et al. Time course analysis of genome-wide identification of mutations induced by and genes expressed in response to carbon ion beam irradiation in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genes. 2021;12(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo J, Meng C, Tang Y, et al. miR-132/212 cluster inhibits the growth of lung cancer xenografts in nude mice. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(11):4115-4122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang X, Chen X, Chen L, et al. Upregulation of the miR-212/132 cluster suppresses proliferation of human lung cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2015;33(2):705-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epperly MW, Gretton JA, DeFilippi SJ, et al. Modulation of radiation-induced cytokine elevation associated with esophagitis and esophageal stricture by manganese superoxide dismutase-plasmid/liposome (SOD2-PL) gene therapy. Radiat Res. 2001;155(1 Pt 1):2-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114-2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts A, Trapnell C, Donaghey J, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Improving RNA-Seq expression estimates by correcting for fragment bias. Genome Biol. 2011;12(3):R22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(5):511-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq--a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(2):166-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang HJ, Kim N, Seong KM, Youn H, Youn B. Investigation of radiation-induced transcriptome profile of radioresistant non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells using RNA-seq. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang HJ, Youn H, Seong KM, Jin YW, Kim J, Youn B. Phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S3 and antiapoptotic TRAF2 protein mediates radioresistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(5):2965-2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skladanowski A, Bozko P, Sabisz M. DNA structure and integrity checkpoints during the cell cycle and their role in drug targeting and sensitivity of tumor cells to anticancer treatment. Chem Rev. 2009;109(7):2951-2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakwe AM, Nguyen T, Athanasopoulos V, Shire K, Frappier L. Identification and characterization of a novel component of the human minichromosome maintenance complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(8):3044-3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuji T, Ficarro SB, Jiang W. Essential role of phosphorylation of MCM2 by Cdc7/Dbf4 in the initiation of DNA replication in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(10):4459-4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishimi Y. A DNA helicase activity is associated with an MCM4, -6, and -7 protein complex. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(39):24508-24513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]