Significant Statement

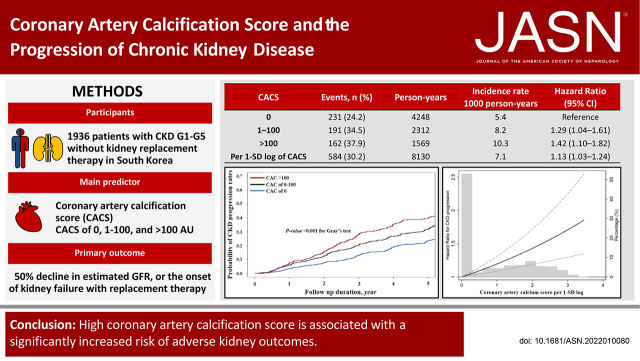

Coronary artery calcification (CAC) is an independent risk factor of cardiovascular disease (CVD) regardless of CKD status, and the CAC score (CACS) may have clinical implications beyond an increased CVD risk. In a prospective cohort study from 1936 patients with CKD in South Korea, higher CACS (1–100 AU and >100 AU) was associated with an increased risk of CKD progression (1.29-fold and 1.42-fold, respectively) compared with a CACS of 0. This association was consistent even after adjustment of nonfatal cardiovascular events being treated as a time-varying covariate. Moreover, the slope of eGFR decline was significantly greater in patients with higher CACS. These findings suggest that CACS may represent potential risk of CKD progression and high odds for adverse CVD.

Keywords: coronary calcification, coronary artery disease, chronic renal disease, clinical nephrology, vascular calcification

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

An elevated coronary artery calcification score (CACS) is associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk in patients with CKD. However, the relationship between CACS and CKD progression has not been elucidated.

Methods

We studied 1936 participants with CKD (stages G1–G5 without kidney replacement therapy) enrolled in the KoreaN Cohort Study for Outcome in Patients With CKD. The main predictor was Agatston CACS categories at baseline (0 AU, 1–100 AU, and >100 AU). The primary outcome was CKD progression, defined as a ≥50% decline in eGFR or the onset of kidney failure with replacement therapy.

Results

During 8130 person-years of follow-up, the primary outcome occurred in 584 (30.2%) patients. In the adjusted cause-specific hazard model, CACS of 1–100 AU (hazard ratio [HR], 1.29; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04 to 1.61) and CACS >100 AU (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.82) were associated with a significantly higher risk of the primary outcome. The HR associated with per 1-SD log of CACS was 1.13 (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.24). When nonfatal cardiovascular events were treated as a time-varying covariate, CACS of 1–100 AU (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.60) and CACS >100 AU (HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.16 to 1.85) were also associated with a higher risk of CKD progression. The association was stronger in older patients, in those with type 2 diabetes, and in those not using antiplatelet drugs. Furthermore, patients with higher CACS had a significantly larger eGFR decline rate.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that a high CACS is associated with significantly increased risk of adverse kidney outcomes and CKD progression.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with CKD.1 Large epidemiologic studies have shown that decreased kidney function and the presence of albuminuria are associated with CVD and mortality irrespective of traditional risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.2,3 In addition, patients with CKD are more likely to experience adverse cardiovascular events (CVEs) before reaching CKD G5D of kidney failure with replacement therapy (KFRT). Therefore, CKD itself has been considered a coronary artery disease equivalent.4,5 Coronary artery calcification (CAC) is a highly specific characteristic of atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis in the coronary arteries. It is generally assessed by an unenhanced low-dose computed tomography (CT) and expressed in the Agatston unit (AU).6 Previous long-term population-based observational studies between the 1990s and early 2000s have shown that CAC has a strong causal association with major cardiovascular outcomes in asymptomatic adults.7–9 Notably, CAC is commonly observed in patients with CKD, and the overall prevalence of CAC, defined as a CAC score (CACS) >0 AU, is 60%.10 Moreover, the prevalence and severity of CAC are higher in patients with KFRT.11 In the analysis of 1541 participants with eGFR of 20–70 ml/min per 1.73 m2 from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study, CAC was independently and significantly related to the risks of CVD.12 As CAC is promoted by traditional and nontraditional risk factors in patients with CKD and these factors also affect kidney function, it can be hypothesized that CAC may predict the future development of adverse kidney outcomes.13 However, several cohort studies with small sample sizes have shown conflicting results,14–16 thus, it is uncertain whether high CACS is a risk factor of the progression of CKD. Therefore, this study aimed to clarify the association between CAC and CKD progression in participants of the KoreaN Cohort Study for Outcomes in Patients With CKD (KNOW-CKD).

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The KNOW-CKD is a nationwide prospective cohort study from nine tertiary care South Korean centers. The study rationale, design, methods, and protocol summary are detailed elsewhere (NCT01630486; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov). Briefly, The KNOW-CKD enrolled Korean patients with CKD between the ages of 20 and 75 years with G1–G5 without kidney replacement therapy (KRT) between 2011 and 2015. The KNOW-CKD study included participants with albuminuria or other early markers of kidney damage and with normal or mildly decreased GFR (CKD G1–2). CKD was defined based on the eGFR, which was calculated using the CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration equation.17 We excluded patients with any of the following: unable or unwilling to provide written consent, previous chronic dialysis or organ transplantation, heart failure (New York Heart Association class 3 or 4), cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class 2 or 3), pregnancy, or history of malignancy. All patients should annually provide blood and urine samples according to the study protocol. They were followed up regularly (1- to 3-month intervals) at the physicians’ discretion. The study was conducted by the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of participating centers.

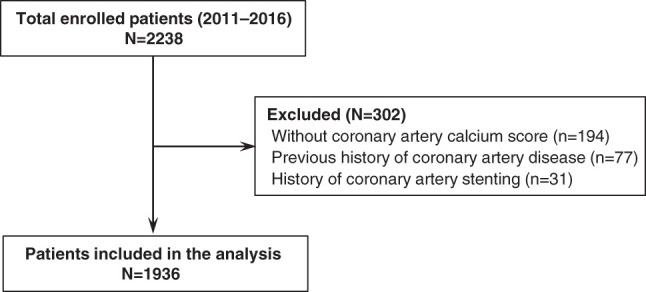

The cohort comprised 2238 participants who voluntarily provided informed consent. Among these, we excluded 194 patients who did not measure CACS. As we intended to explore the clinical implication of CACS with respect to CKD progression in patients without previous coronary artery disease, we further excluded patients with previous history of coronary artery disease (n=77) and coronary artery stenting (n=31) (Figure 1). Previous coronary artery disease was confirmed by study investigators at participating centers. Finally, 1936 participants were included in the study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study subjects.

Data Collection

Baseline demographics and laboratory data were retrieved from the electronic data management system (PhactaX, Seoul, Republic of Korea). Demographic data including age, sex, smoking history, etiology of CKD, comorbidities, and medications were collected at the time of screening. Height was measured using a digital stadiometer while participants stood barefoot. Body weight (kg) was measured using standard methods in light clothes without shoes. Height and weight were measured to the nearest 1 cm and 0.1 kg. Body mass index was calculated as the weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). Smoking status was divided into three categories as never, former, and current. Education level was categorized as low, less than middle school; middle, middle school; and high, more than middle school. Hypertension was defined as self-reported hypertension, systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, or current use of antihypertensive drugs. Antihypertensive drugs included angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers (dihydropyridine and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers), β-blockers, and diuretics. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a history of diabetic mellitus, fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dl, or use of glucose-lowering drugs. In this study, we included only patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Lipid-lowering drugs included statins, ezetimibe, and fibrates. The Charlson comorbidity index score was used to reflect disease burden at baseline.

BP measurements were performed by a trained nurse at each clinic according to the standardized protocol as suggested by the American Heart Association.18 BP was measured after >5 min of rest in a sitting position at the clinic office using a calibrated oscillometer electronic sphygmomanometer or mercury sphygmomanometer. The electronic device was validated by comparison of the device readings (four in all) alternating with five mercury readings taken by two trained observers. The mean of three BP readings was used as the BP value for each visit.19

After overnight fasting, venous samples were collected to determine hemoglobin, BUN, creatinine, uric acid, total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, albumin, calcium, phosphate, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and intact parathyroid hormone (intact-PTH) levels. Fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) was measured by ELISA at baseline (Immutopics, San Clemente, CA). Random urine samples from midstream collection were used to measure the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR). We used a creatinine method that requires calibration traceable to isotope dilution mass spectrometry. CKD classification was followed by the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines.20

Measurement of CACS

CACS was determined by electrocardiography-gated coronary 64-slice multidetector CT scanning of the thorax according to the standard protocol. Calcification was defined as an area of hyper-attenuation greater than 130 Hounsfield units within a 1-mm2 area. The quantitative CACS was calculated using the Agatston method on a digital workstation by cardiac radiologists at each participating center.6 They were all blinded to patient information. Participants were categorized into three groups according to baseline CACS (CACS of 0, CACS of 1–100 AU, and CACS >100 AU). In addition, CACS per 1-SD log was calculated and used as a continuous variable for the analysis.

Study End Point

The primary outcome of interest was a composite of the first occurrence of a 50% decline in eGFR from the baseline value or the onset of KFRT. KFRT was defined as CKD G5 requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation. Patients with CKD G3 and greater were closely observed for the occurrence of adverse clinical events and had visited each participating center at 1- to 3-month intervals. Patients who reached the end points were reported by each center. Then, we cross-checked between centers if the outcome events were correct. The secondary end points were the separate components of the primary outcome and all-cause mortality. The study observation period ended on March 31, 2019.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were expressed as mean with SD or median with interquartile range (IQR) for skewed data. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers of participants with percentage. To compare the difference according to CAC groups, a one-way analysis of variance was used for continuous and categorical variables. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for data with skewed distribution. The multivariable cause-specific hazard models were used to assess the association of CACS with CKD progression. To validate the results of the primary analysis, we further constructed subdistribution hazard models. In these two models, a death that occurred before reaching the primary outcome was treated as a competing risk. To be more specific, subjects experiencing a competing risk event remain in the risk set in the subdistribution model, whereas they are removed in the cause-specific model.21 Model 1 represents unadjusted hazard ratios (HRs). Model 2 adjusted for sex, age, Charlson comorbidity index, smoking history, education level, body mass index, and etiology of CKD. We also created model 3 after adjustment for BP and laboratory parameters such as eGFR, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, hs-CRP, and medications including antihypertensive (renin-angiotensin system blockers, calcium channel blockers, β-blockers, and diuretics) and lipid-lowering drugs (statins, ezetimibe, and fibrates), in addition to factors included in model 2. In model 4, phosphate, intact-PTH, FGF-23, and UPCR were further added. Because CACS is a strong predictor of CVD and there is a significant connection between CVD and CKD, we further examined relative contribution of nonfatal CVEs to CKD progression. To this end, we constructed a time-varying model, in which the occurrence of nonfatal CVEs before the primary outcome was treated as a time-varying covariate. The nonfatal CVEs were defined as myocardial infarction, unstable angina, heart failure, and stroke. Other repeated variables such as BP, body mass index, UPCR, and eGFR were also considered as time-varying covariates. There were missing values for education level, BP, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, hs-CRP, phosphate, UPCR, intact-PTH, and FGF-23, which were less than 5% of all measurements (Supplemental Table 1). We assumed missing data as missing at random. The multiple imputation by chained equations method was used to impute 10 independent copies of the data for the analyses. The results of hazard models were presented as HRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The probability of kidney survival rates was estimated with cumulative incidence function and compared by Gray’s test.22 Survival time was defined as the time interval between enrollment and the first onset of clinical outcomes. Patients who were lost to follow-up were censored at the date of the last examination. To validate our findings, we performed several sensitivity analyses. First, we examined the association of CACS with the risk of CKD progression after excluding 116 (6.1%) patients with eGFR <15 ml per min per 1.73 m2 at baseline because CKD G5 is considered equivalent to kidney failure requiring KRT. Second, this association was further tested after including patients with previous coronary artery disease. In this analysis, we excluded patients with prior coronary stenting (n=31) because the presence of stent can interfere with the calculation of CACS. Third, we also analyzed the association after excluding patients with calcium-based phosphate binders (n=164) because this medication can be a potential confounder or effect modifier. Finally, we further analyzed using two different CACS categories with 0, 1–400, and >400, and 0, 1–100, 101–400, and >400. A restricted cubic spline curve was used to reveal the association between log CACS and the HRs for the composite kidney outcome. In addition, we further examined effect modification among prespecified subgroups by sex (male or female), age (<60 years or ≥60 years), smoking history (never or former and current), T2DM (without or with), antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin or clopidogrel (without or with), statins (without or with), systolic BP (<140 mm Hg or ≥140 mm Hg), LDL level (<100 mg/dl or ≥100 mg/dl), severity of CKD (G1–2 or G3–5ND), and UPCR (<1.0 g/gCr or ≥1.0 g/gCr). Finally, the rate of kidney function decline per year was assessed using the slope of eGFR obtained from a generalized linear mixed model. The statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 15.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics according to CACS categories are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 53.2 years and 60.7% were male. The mean eGFR was 51.5 (SD, 30.3) ml/min per 1.73 m2 and the median CACS was 0.5 (IQR, 0.0–75.4) AU. Graphs showing distribution of CACS in all patients and patients with and without CKD progression are presented in Supplemental Figure 1. Compared with patients without CAC, those with CACS of 1–100 and CACS >100 were more likely to be older and male, and more likely to have T2DM and to be treated with antiplatelet drugs (aspirin and clopidogrel) and lipid-lowering medications. In addition, these patients had higher levels of body mass index, BP, glucose, triglycerides, hs-CRP, intact-PTH, and proteinuria, but had lower levels of total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and eGFR.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to coronary artery calcification score

| Coronary Artery Calcification Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Overall | 0 | 1–100 | >100 | P |

| Participants | 1936 | 956 | 553 | 427 | |

| CAC score (AU) | |||||

| Median, (IQR)a | 0.5 (0–75.4) | 0 (0–0) | 15.7 (4.8–42.3) | 352.1 (170.3–744.0) | <0.001 |

| Mean (min, max) | 141.9 (0, 4307) | 0 (0, 0) | 26.8 (0.3, 97.5) | 609.0 (100.5, 4307) | <0.001 |

| Age | 53.2 (12.0) | 47.6 (11.5) | 56.5 (10.1) | 61.4 (8.7) | <0.001 |

| Men | 1176 (60.7) | 489 (51.2) | 361 (65.3) | 326 (76.3) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | <0.001 | ||||

| Never | 1046 (54.0) | 593 (62.0) | 270 (48.8) | 183 (42.9) | |

| Former | 578 (29.9) | 223 (23.3) | 181 (32.7) | 174 (40.7) | |

| Current | 312 (16.1) | 140 (14.6) | 102 (18.4) | 70 (16.4) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.7 (3.2) | 24.3 (3.2) | 25.0 (3.2) | 25.1 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1864 (96.3) | 895 (93.6) | 546 (98.7) | 423 (99.1) | <0.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 612 (31.6) | 128 (13.4) | 209 (37.8) | 275 (64.4) | <0.001 |

| Arrhythmia | 44 (2.3) | 13 (1.4) | 17 (3.1) | 14 (3.3) | 0.12 |

| Education level | <0.001 | ||||

| Low | 231 (11.9) | 68 (7.2) | 94 (17.1) | 69 (16.2) | |

| Middle | 904 (36.8) | 429 (44.9) | 265 (48.1) | 210 (49.3) | |

| High | 799 (41.3) | 459 (48.0) | 193 (35.0) | 147 (34.5) | |

| Etiology of kidney disease | <0.001 | ||||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 417 (21.5) | 58 (6.1) | 143 (25.9) | 216 (50.6) | |

| Hypertensive nephropathy | 346 (17.6) | 126 (13.2) | 139 (25.1) | 81 (19.0) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 725 (37.4) | 484 (50.6) | 166 (30.0) | 75 (17.6) | |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 344 (17.8) | 250 (26.2) | 73 (13.2) | 21 (4.9) | |

| Others | 104 (5.4) | 38 (4.0) | 32 (5.8) | 34 (8.0) | |

| Antihypertensive medication | |||||

| ACEi or ARB | 1555 (80.3) | 758 (79.3) | 460 (83.2) | 337 (78.9) | 0.04 |

| β-Blocker | 452 (23.3) | 182 (19.0) | 139 (25.1) | 131 (30.7) | <0.001 |

| DCCB or NDCCB | 828 (42.8) | 315 (33.0) | 253 (45.8) | 260 (60.9) | 0.004 |

| Diuretics | 594 (30.7) | 210 (22.0) | 196 (35.4) | 188 (44.0) | <0.001 |

| Antithrombotic medication | |||||

| Aspirin | 477 (24.6) | 153 (16.0) | 164 (29.7) | 160 (37.5) | <0.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 51 (2.6) | 12 (1.3) | 16 (2.9) | 23 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin | 23 (1.2) | 6 (0.6) | 13 (2.4) | 4 (0.9) | 0.07 |

| Lipid-lowering medication | |||||

| Statins | 978 (50.5) | 399 (41.7) | 306 (55.3) | 273 (63.9) | <0.001 |

| Ezetimibe | 122 (6.3) | 49 (5.1) | 35 (6.3) | 38 (8.9) | 0.06 |

| Fibrates | 54 (2.8) | 25 (2.6) | 17 (3.1) | 12 (2.8) | 0.45 |

| Calcium-based phosphate binders | 164 (8.5) | 92 (9.6) | 73 (7.8) | 29 (6.8) | 0.17 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 127.8 (16.0) | 125.1 (14.1) | 129 (16.0) | 132.1 (18.6) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 77.2 (10.9) | 77.5 (10.5) | 77.7 (11.0) | 75.9 (11.8) | 0.004 |

| WBC count (10^3/μl) | 6.5 (1.9) | 6.4 (1.9) | 6.4 (1.7) | 6.8 (1.9) | 0.002 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.9 (2.0) | 13.1 (1.8) | 12.8 (2.1) | 12.4 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | 27.6 (15.3) | 24.3 (13.2) | 29.3 (16.5) | 32.8 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.8 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 51.5 (30.3) | 58.5 (32.8) | 48.4 (28.0) | 39.9 (22.4) | <0.001 |

| eGFR, categories | <0.001 | ||||

| ≥90 | 326 (17.2) | 250 (26.7) | 58 (10.7) | 18 (4.3) | |

| 60–90 | 367 (19.3) | 192 (20.5) | 121 (22.2) | 54 (13.0) | |

| 30–59 | 629 (33.2) | 292 (31.1) | 176 (32.3) | 161 (38.8) | |

| 15–29 | 459 (24.2) | 168 (17.9) | 148 (27.2) | 143 (34.5) | |

| <15 (nondialysis) | 116 (6.1) | 36 (3.8) | 41 (7.5) | 39 (9.4) | |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.1 (0.5) | 9.1 (0.5) | 9.0 (0.5) | 9.0 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Phosphate (mg/dl) | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 6.9 (1.9) | 6.7 (1.9) | 7.0 (1.8) | 7.4 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.1 (0.4) | 4.2 (0.3) | 4.1 (0.4) | 4.1 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 109.8 (38.5) | 101.2 (24.9) | 114.7 (43.5) | 122.8 (50.2) | <0.001 |

| Lipid profiles | |||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 174.9 (38.7) | 178.5 (36.4) | 173.4 (39.0) | 168.6 (42.2) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 157.7 (99.7) | 146.6 (91.7) | 166.3 (99.5) | 171.2 (113.7) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 49.3 (15.4) | 52.2 (15.7) | 47.5 (15.0) | 45.4 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 97.6 (31.7) | 100.4 (30.0) | 96.8 (33.6) | 92.3 (32.1) | <0.001 |

| Electrolyte | |||||

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 140.8 (2.4) | 140.9 (2.2) | 140.8 (2.5) | 140.8 (2.6) | 0.34 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.5 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.7 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 105.4 (3.5) | 105.4 (3.2) | 405.4 (3.7) | 105.6 (3.8) | 0.80 |

| Total CO2 (mmol/L) | 25.8 (3.5) | 26.0 (3.5) | 25.8 (3.7) | 25.3 (3.5) | 0.01 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L)a | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) | 0.5 (0.2–1.6) | 0.6 (0.3–1.7) | 0.7 (0.3–1.8) | 0.004 |

| Intact-PTH (pg/ml)a | 51 (33.2–81.1) | 47 (30.9–73.0) | 53.3 (34.1–83.6) | 57.0 (34.0–106.5) | <0.001 |

| FGF-23 (RU/ml)a | 19.1 (1.61–34.1) | 16.4 (0.85–30.9) | 21.2 (2.3–38.3) | 21.8 (3.7–39.2) | <0.001 |

| Urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio (g/gCr)a | 0.6 (0.2–1.6) | 0.5 (0.1–1.3) | 0.7 (0.2–1.7) | 0.8 (0.4–2.5) | <0.001 |

| 24-h urinary protein (mg/d)a | 533.5 (160.0–1550.4) | 431 (132.1–1163.9) | 636.3 (195.2–1675.0) | 762.8 (250.2–2420.1) | <0.001 |

Values for categorical variables are given as number (percentage); values for continuous variables as mean (SD), mean (min, max), or median (IQR). eGFR was calculated using the CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. Conversion factors for units: serum creatinine in mg/dl to μmol/L, × 88.4; urea nitrogen in mg/dl to mmol/L, × 0.357; cholesterol in mg/dl to mmol/L, × 0.02586. CAC, coronary artery calcification; AU, Agatston unit; IQR, interquartile range; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; DCCB, dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker; NDCCB, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker; WBC, white blood cell; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; PTH, parathyroid hormone; FGF-23, fibroblast growth factor-23; RU; relative unit.

Variables were compared by the Kruskal–Wallis method.

Association between CACS and CKD Progression

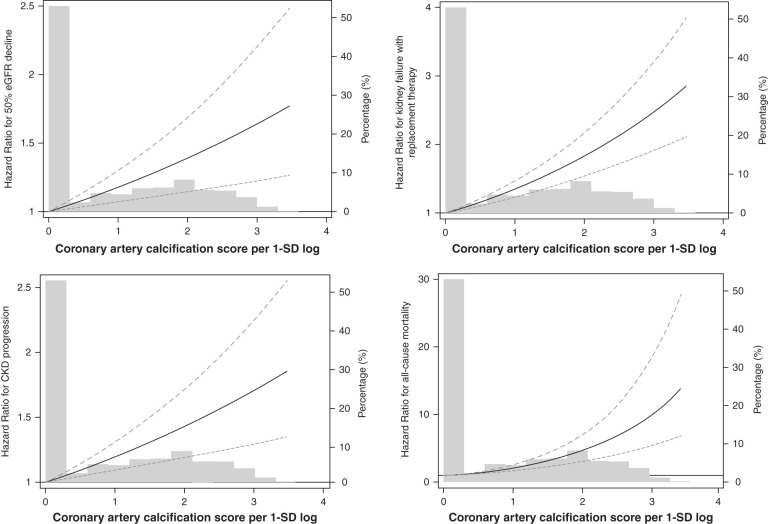

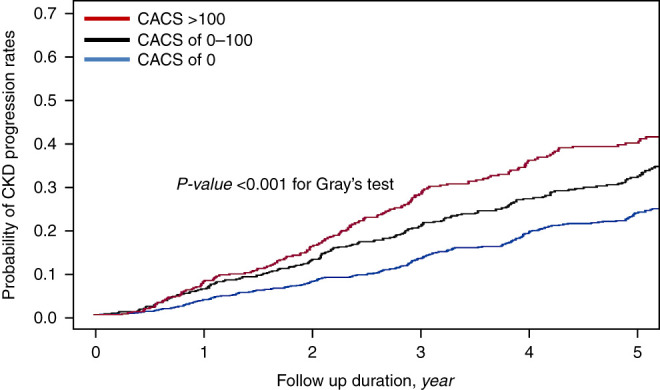

During 8130 person-years of follow-up, the primary outcome occurred in 584 (30.2%) patients. The overall incidence rate was 5.4, 8.2, and 10.3 per 1000 person-years in patients across the CACS categories, respectively (P<0.001) (Table 2). In addition, mean time to event occurrence was significantly shorter (3.2 versus 2.9 versus 2.5 years) and cumulative adverse kidney events were significantly higher in patients with CACS of 1–100 and CACS >100 than in those without CAC (Figure 2). The unadjusted HRs for CACS of 1–100 and CACS >100 were 1.54 (95% CI, 1.27–1.86) and 1.96 (95% CI, 1.60–2.41), respectively, compared with CAC of 0. This association was consistent for sequential adjustment of demographics and laboratory parameters (models 2–4). In the final model (model 4), patients with CACS of 1–100 and CACS >100 were associated with a 1.29-fold (95% CI, 1.04–1.61) and 1.42-fold (95% CI, 1.10–1.82) higher risk of the primary outcome. Furthermore, when CACS was used as a continuous variable, the HR per 1-SD log of CACS was 1.13 (95% CI, 1.03–1.24). Another competing risk model with subdistribution hazard model yielded similar results (Supplemental Table 2). Restricted cubic spline curve analysis clearly showed a linear relationship between CACS and CKD progression (Figure 3). Finally, the slope of eGFR decline per year was significantly greater in patients with CACS of 1–100 (−3.01 ml/min per 1.73 m2; 95% CI, −3.44 to −2.58) and CACS >100 (−4.18 ml/min per 1.73 m2; 95% CI, −4.71 to −3.66) compared with CACS of 0 (−2.55 ml/min per 1.73 m2; 95% CI, −2.87 to −2.22) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for the risk of composite kidney outcome according to coronary artery calcification score

| CACS | Events, n (%) | Person- Years | Incidence Rate 1000 Person-Years | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 231 (24.2) | 4248 | 5.4 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 1–100 | 191 (34.5) | 2312 | 8.2 | 1.54 (1.27–1.86) | 1.44 (1.17–1.78) | 1.31 (1.06–1.63) | 1.29 (1.04–1.61) |

| >100 | 162 (37.9) | 1569 | 10.3 | 1.96 (1.60–2.41) | 1.81 (1.42–2.30) | 1.36 (1.07–1.73) | 1.42 (1.10–1.82) |

| Per 1-SD log of CACS | 584 (30.2) | 8130 | 7.1 | 1.29 (1.19–1.39) | 1.23 (1.12–1.34) | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | 1.13 (1.03–1.24) |

The hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) is reported for each model. The composite kidney outcome was defined as the first occurrence of a 50% decline in eGFR from the baseline value, or the onset of kidney failure with replacement therapy. CACS, coronary artery calcification score.

Model 1: a crude analysis without adjustment.

Model 2: adjusted for sex, age, Charlson comorbidity index, smoking status, education level, body mass index, and etiology of kidney disease.

Model 3: Model 2 + BP, eGFR, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and medications (antihypertensive drugs and lipid-lowering drugs).

Model 4: Model 3 + phosphate, intact parathyroid hormone, fibroblast growth factor-23, and urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio.

Figure 2.

The probability of kidney survival rates according to coronary artery calcification score categories. The probability of kidney survival rates was estimated with cumulative incidence function and compared by Gray’s test (P<0.001). CACS, coronary artery calcification score.

Figure 3.

Cubic spline analysis for risk of adverse clinical events by coronary artery calcification score. Coronary artery calcification score was calculated as log transformation and expressed as coronary artery calcification score per 1-SD log.

Table 3.

Annual rates of kidney function decline according to coronary artery calcification score categories

| CACS | Slope of eGFR Decline (ml/min per 1.73 m2 per Year) | 95% CI | P for Difference between Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1–100 | >100 | |||

| 0 | −2.55±0.16 | −2.87 to −2.22 | — | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| 1–100 | −3.01±0.22 | −3.44 to −2.58 | — | <0.001 | |

| >100 | −4.18±0.27 | −4.71 to −3.66 | — | ||

Slope of eGFR decline was expressed as mean±SD. CACS, coronary artery calcification score; CI, confidence interval.

Secondary Outcome Analyses

To evaluate what extent the risk of adverse kidney outcome with CACS was affected by CVEs, we performed time-varying analysis. During the follow-up period, nonfatal CVEs occurred in 118 (6.0%) participants. In keeping with the results of primary analysis, the HRs for CAC of 1–100 and CACS >100 were 1.31 (95% CI, 1.07 to 1.60) and 1.46 (95% CI, 1.16 to 1.85), respectively (Supplemental Table 3). Interestingly, in this time-varying model, nonfatal CVEs were associated with a 1.25-fold (95% CI, 1.02 to 1.79) higher risk of CKD progression, suggesting a significant contribution of nonfatal CVEs to the adverse kidney outcome. We further evaluated the association of CACS with the individual components of the kidney outcome and all-cause mortality. In both categorical and continuous models, the significant association mostly persisted. For the outcome of ≥50% decline in eGFR, CACS of 1–100 and CACS >100 were associated with a 1.28-fold (95% CI, 0.99 to 1.64) and 1.34-fold (95% CI, 1.00 to 1.80) increased risk for eGFR decline (Supplemental Table 4). In addition, the HRs for KFRT were 1.19 (95% CI, 0.94 to 1.52) for CAC of 1–100 and 1.54 (95% CI, 1.17 to 2.02) for CACS >100, respectively. For 1-SD higher level of log CAC, the HRs were 1.15 (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.29) for ≥50% decline in eGFR and 1.19 (95% CI, 1.07 to 1.32) for KFRT. For all-cause mortality, CAC >100 was associated with 2.34-fold (95% CI, 1.24 to 4.42) higher risk of all-cause mortality (Supplemental Table 5). In addition, the risk of all-cause mortality was 1.65-fold (95% CI, 1.28 to 2.12) increased for per 1-SD higher log of CACS.

Sensitivity Analysis

In sensitivity analysis after excluding 116 (6.1%) patients with eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at baseline, CACS of 1–100 (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.60) and CACS >100 (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.89) were significantly associated with a higher risk of the primary kidney outcome (Supplemental Table 6). This association was similar in continuous modeling; for every 1-SD increase in log CACS, there was a 1.13-fold (95% CI, 1.02 to 1.26) higher risk of the progression of CKD. This association was consistent in analysis including patients with previous coronary artery disease (Supplemental Table 7) and in analysis excluding patients with calcium-based phosphate binders (Supplemental Table 8). Furthermore, in analyses using two different CACS categories with 0, 1–400, and >400, and 0, 1–100, 101–400, and >400, the graded association of CACS and risk of CKD progression remained unchanged (Supplemental Table 9).

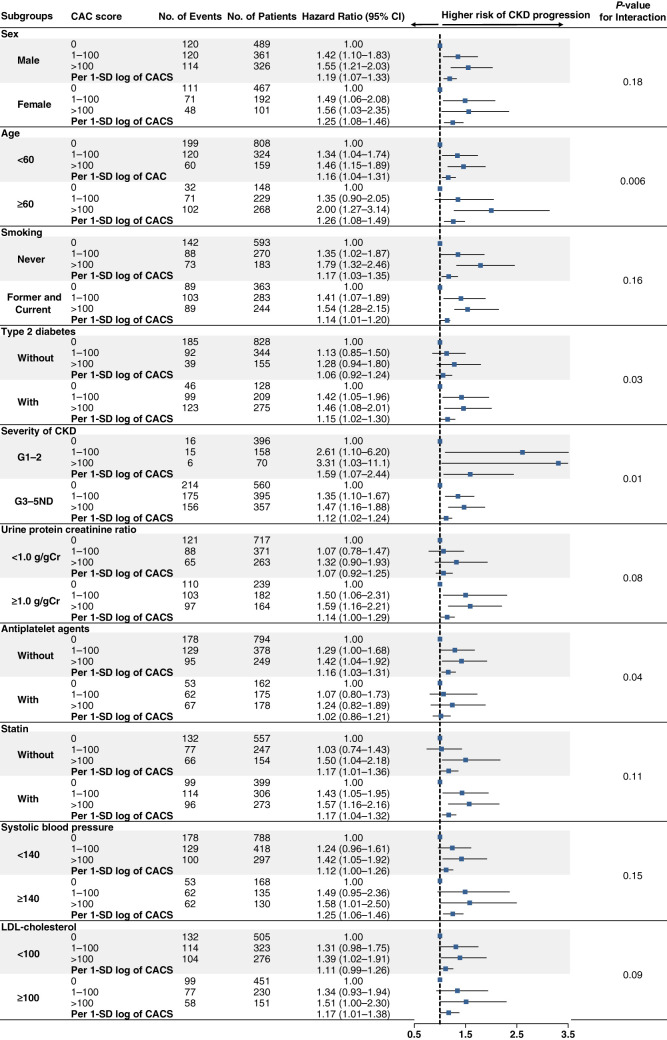

Subgroup Analyses

To evaluate the effect modification of subgroups on the relationship between CACS and CKD progression, we tested interactions among prespecified subgroups. P values for interactions were >0.05 for the subgroups by sex, smoking, statin, proteinuria, BP, and LDL cholesterol level. However, there were significant interactions of age, T2DM, severity of CKD, and the use of antiplatelet drugs with CACS categories. The significant association between CACS and CKD progression was more pronounced in older patients and those with T2DM and nonuse of antiplatelet drugs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios for CKD progression according to coronary artery calcification score categories and per 1-SD log of coronary artery calcification score, stratified by subgroups. Each hazard ratio was adjusted for covariates including sex, age, Charlson comorbidity index, smoking status, education level, body mass index, etiology of kidney disease, BP, eGFR, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, medications (antihypertensive drugs and lipid-lowering drugs), phosphate, intact parathyroid hormone, urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio, and fibroblast growth factor-23. CAC, coronary artery calcification; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to explore the clinical implications of CAC in the progression of CKD. The findings from the KNOW-CKD clearly showed that the risk of CKD progression was significantly higher in patients with CAC than in those without CAC. We validated this association by various analytical approaches. This association was more pronounced in older patients and those with T2DM and nonuse of antiplatelet drugs. Moreover, there was a graded decline in eGFR in patients with higher CACS categories. Based on these findings, this suggests that high CACS is significantly associated with the future development of adverse kidney outcomes in patients with CKD.

CAC is a noninvasive, direct indicator of coronary artery atherosclerosis and is now an established risk factor for CVD and mortality in patients at high risk of CVD and asymptomatic individuals.23 In addition, CAC is also associated with an increased risk of non-CVD such as cancer, kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hip fracture.24 Thus, CAC has emerged as a risk integrator to reflect lifetime exposure to both measured and unmeasured risk factors that are shared by both CVD and non-CVD outcomes. In patients with CKD, atherosclerosis and valvular calcification are common.25 However, there are sparse data for CAC in CKD patients without KRT. The CRIC study investigators reported that CAC is independently associated with CVD, myocardial infarction, and heart failure in 1514 patients with eGFR of 20–70 ml/min per 1.73 m2 who had no history of CVD. Furthermore, in terms of risk prediction for CVEs in these patients, CAC outperforms traditional cardiovascular risk factors.12 In this study, we particularly focused on the relationship between CAC and the progression of CKD and found that high CACS was independently associated with adverse kidney outcomes. In line with our findings, Lamarche et al. reported that CAC was associated with deterioration of kidney function, shorter time to ESKD, and increased all-cause mortality in 178 patients with CKD G3–5.14 In addition, Garland et al. also showed that higher CACS was significantly associated with greater decline in eGFR over 1 year in 125 patients with CKD G3–5.15 In contrast, in a cross-sectional study from the Renal Research Institute-CKD cohort, CAC was not related to indicators of kidney dysfunction in 106 patients with CKD G3–4.16 It should be noted that all of these studies had limited sample size with <200 patients. The absence of data in patients with CKD G1–2 is also a critical shortcoming given high prevalence of CAC even in these patients with low CKD risk category.13 In this regard, our findings from the KNOW-CKD are noteworthy because all 1936 patients underwent a CT scan for measurement of CAC at baseline and had CKD G1–5ND with 624 (32.2%) patients belonging to CKD G1–2. In addition, the composite kidney outcome occurred in 584 (30.2%) patients during the mean follow-up of 4.1 years. Such adequate sample size, various CKD risk categories, and sufficient event number and follow-up duration allowed us to appropriately analyze the association between CAC and CKD progression.

Our time-varying analysis showed that nonfatal CVEs significantly contributed to the adverse kidney outcome and adjustment of CVEs did not change the relationship between CACS and CKD progression. Given that CACS is a strong predictor of CVD and CVD is also closely related to CKD, these findings suggest that CVD may partly explain the association of CACS with the risk of CKD progression. Although in-depth analysis on absolute contribution of non-CVEs to this relationship was not feasible, the magnitude of HR for nonfatal CVEs in the time-varying model for the kidney outcome appeared to be lower than expected. Of note, there were only 118 nonfatal CVEs in our cohort despite a substantial number of patients with CACS >100 (n=427, 22.1%) Presumably, many patients with high CACS were asymptomatic, and thus overt coronary artery disease was not detected until the artery became severely narrowed. Despite the highly prevalent patients with CACS in our cohort, the incidence of CVEs was lower than in other Western countries as we previously reported.26 Nevertheless, the persistently significant association even after adjustment of nonfatal CVEs indicates that CACS may have clinical implications with respect to CKD progression beyond CVD.

In this study, there was a significant interaction between T2DM and CAC was more strongly associated with CKD progression in patients with T2DM than in those without T2DM. This association was not surprising because T2DM is a well-known risk factor for the development and progression of CKD, and CAC is highly prevalent in patients with diabetes.27 In addition, under T2DM conditions, unfavorable conditions with inflammation, oxidative stress, and advanced glycation end products can promote vascular calcification.28 In this study, the median CACS was 69.9 (IQR, 2.4–374) AU and the proportion of CAC >100 AU was 45.2% in a patient with T2DM, as compared with 0.0 (IQR, 0.0–10.6) AU and 11.7% in those without T2DM. Thus, it can be presumed that T2DM and CAC synergistically act in the progression of CKD.

In the subgroup analysis, the higher risk of the primary kidney outcome in higher CACS was more prominent in patients without the use of antiplatelet drugs. Miedema et al. reported that subjects with CACS ≥100 had positive risk/benefit estimates for aspirin use, however those with CACS of zero were expected to suffer net harm from aspirin usage in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis participants for the prevention of CVD.29 Similarly, in the Dallas Heart Study, high CACS was helpful to identify individuals who could benefit from primary prevention aspirin therapy.30 In patients with CKD, the use of an antiplatelet agent is suggested for the prevention of CVD in those at risk of atherosclerotic events.31 However, the benefits of antiplatelet agents for CKD patients are potentially outweighed by bleeding risks and its protective effect against the progression of CKD is uncertain.32 Our findings can support previous studies suggesting that the presence of CAC may guide the use of antiplatelet agents. Given the lack of randomized controlled trials regarding this issue in patients with CKD, we are looking forward to the results from two ongoing randomized controlled trials: “ALTAS-CKD” (antiplatelet therapy for the prevention of atherosclerosis in CKD) and “LEDA” (renal disease progression by aspirin in diabetic patients).33,34

To the best of our knowledge, the KNOW-CKD study included the largest number of patients with CAC measurement in patients with CKD. With these data, we were able to perform in-depth analyses to delineate the relationship between CAC and the progression of CKD. However, our study has several limitations that should be considered. First, because of the observational nature of this study, the causal relationship between CAC and the risk of CKD progression could not fully be established and residual confounding remains despite our efforts to control important confounders. This significant relationship may be simply attributed to a high prevalence of vascular calcification at lower eGFR. To mitigate this concern, we further performed a sensitivity analysis excluding patients with eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and found consistent results. Moreover, 228 (36.5%) patients already had CAC among 624 patients with eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and the risk of the primary kidney outcome was also significantly higher in these patients with CAC. Thus, the association between CAC and CKD progression is likely to be explained by kidney-specific mechanisms for atherosclerosis such as CKD-mineral bone metabolism in addition to traditional risk factors. Second, although we rigorously adjusted for the potential factors related to CAC and CKD progression, we had a methodologic issue on measurement of FGF-23 because we measured serum C-terminal FGF-23.35 This method resulted in notably lower FGF-23 levels in our cohort than measuring the intact form of FGF-23 in plasma.36,37 Recently, it has been reported that measuring intact form FGF-23 from plasma can provide higher accuracy than that from serum.38 Nevertheless, in model 4 adjusted for bone and mineral disorder–related markers, we observed consistent results. Third, although all participating centers followed the same protocol using 64-slice multidetector CT for CACS evaluation,39 the readings were not cross-checked among centers. Fourth, KNOW-CKD cohort involved a single ethnic people, so CAC as a marker of CKD progression needs to be further tested in other populations.

In summary, this study showed that CAC is significantly associated with an increased risk of adverse kidney outcomes. Clinical significance of CAC is more evident in older patients and those with T2DM and nonuse of antiplatelet drugs. Thus, high CACS can represent potential CKD risk and high odds for adverse CVD. Future studies should address proper preventive measures in patients with CKD and CAC.

Disclosures

S.H. Han reports serving as a subeditor of Nephrology and serving as a scientific advisor or member of the Korean Society of Nephrology. J. Lee reports research funding from Astellas Pharma Korea, Inc. K.H. Oh reports research funding from Fresenius Medical Care, Korea. S. Sung reports research funding from Korea Otsuka Pharmaceutical Company, and is on the speakers bureau with Baxter Korea. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Program funded by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011E3300300, 2012E3301100, 2013E3301600, 2013E3301601, 2013E3301602, 2016E3300200, 2016E3300201, 2016E3300202, 2019E320100, 2019E320101, 2019E320102, and 2022-11-007). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The institutional review board of each participating clinical center approved the study protocol as follows: Seoul National University Hospital (1104-089-359), Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (B-1106/129-008), Yonsei University Severance Hospital (4-2011- 0163), Kangbuk Samsung Medical Center (2011-01-076), Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (KC11OIMI0441), Gil Hospital (GIRBA2553), Eulji General Hospital (201105-01), Chonnam National University Hospital (CNUH-2011-092), and Pusan Paik Hospital (11-091). The authors thank the clinical research coordinators of each participating center for their dedication during patient recruitment and data acquisition.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: The KoreaN Cohort Study for Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease (KNOW-CKD), Curie Ahn, Kook-Hwan Oh, Seung Seok Han, Hajeong Lee, Young Ok Koh, Jeongok So, Seonui Ko, Aram Lee, Dong Wan Chae, Jong Cheol Jeong, Hyun Jin Cho, Jung Eun Oh, Kyu Jin Lee, Tae-Hyun Yoo, Kyu Hun Choi, Seung Hyeok Han, Jung Tak Park, Hui Kyung Hong, Ji Young You, Kyu-Beck Lee, Young Youl Hyun, Hyun Jung Kim, Yong-Soo Kim, Yaeni Kim, Sol Ji Kim, Wookyung Chung, Ji Yong Jung, Kwon Eun Jin, Suah Sung, Hyang Ki Min, Ja Yung Ku, Soo Wan Kim, Seong Kwon, Eun Hui Bae, Chang Seong Kim, Ha Yeon Kim, Tae Ryom Oh, Hong Sang Choi, Minah Kim, Chana Myeong, Jeong Ho Lee, Ji Seon Lee, Yeong Hoon Kim, Sun Woo Kang, Tae Hee Kim, Yunmi Kim, Young Eun Oh, Ja Ryong Koo, Jang Won Seo, Seon Ha Baek, Myung Sun Kim, Tae Ik Chang, Kyoung Sook Park, Aei Kyung Choi, Yun Kyu Oh, Jung Pyo Lee, Jeong Hwan Lee, Jeong Mi Park, Eun Young Seong, Song Sang Heon, Harin Rhee, Hyo Jin Kim, Kim Da Woon, Seung Hee Ji, Young Taek Kim, Ki Ryang Na, Dae Eun Choi, Young Rok Ham, Eu Jin Lee, and Yoon Jung Cha

Author Contributions

S.H. Han and H.R. Yun conceptualized the study and were responsible for data curation, investigation, project administration, resources, software, validation, and visualization; T.I. Chang, S.H. Han, S.W. Kang, J. Lee, K.B. Lee, K.H. Oh, J.T. Park, S. Sung, and T.H. Yoo were responsible for supervision; S.H. Han, Y.S. Joo, H.W. Kim, N.H. Son, and H.R. Yun were responsible for methodology; S.H. Han, N.H. Son, and H.R. Yun were responsible for formal analysis; H.R. Yun wrote the original draft; and S.H. Han reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

The data used in this study are available from the KNOW-CKD investigator Team upon reasonable request.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2022010080/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. The number of imputed missing data.

Supplemental Table 2. Subdistribution hazard model for the risk of composite kidney outcome.

Supplemental Table 3. Time-varying model for risk of composite kidney outcome according to coronary artery calcification score.

Supplemental Table 4. Hazard ratios for the risk of 50% estimated glomerular filtration rate decline and kidney failure with replacement therapy according to coronary artery calcification score.

Supplemental Table 5. Hazard ratios for the risk of all-cause mortality according to coronary artery calcification score.

Supplemental Table 6. Hazard ratios for the risk of composite kidney outcome according to coronary artery calcification score in patients with eGFR ≥15.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Supplemental Table 7. Hazard ratios for the risk of composite kidney outcome in patients with previous coronary artery disease.

Supplemental Table 8. Hazard ratios for the risk of composite kidney outcome in patients without calcium-based phosphate binders.

Supplemental Table 9. Hazard ratios for the risk of 50% estimated glomerular filtration rate decline and kidney failure with replacement therapy according to different coronary artery calcification score categories.

Supplemental Figure 1. Distribution of coronary artery calcification score.

References

- 1.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, et al. ; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: A collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 375: 2073–2081, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grams ME, Astor BC, Bash LD, Matsushita K, Wang Y, Coresh J: Albuminuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate independently associate with acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1757–1764, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, House A, Rabbat C, Fok M, et al. : Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: A systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2034–2047, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jankowski J, Floege J, Fliser D, Böhm M, Marx N: Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: Pathophysiological insights and therapeutic options. Circulation 143: 1157–1172, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M Jr, Detrano R: Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 15: 827–832, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann U, Massaro JM, Fox CS, Manders E, O’Donnell CJ: Defining normal distributions of coronary artery calcium in women and men (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 102: 1136–1141, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oei HH, Vliegenthart R, Hak AE, Iglesias del Sol A, Hofman A, Oudkerk M, et al. : The association between coronary calcification assessed by electron beam computed tomography and measures of extracoronary atherosclerosis: The Rotterdam Coronary Calcification Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 39: 1745–1751, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmermund A, Möhlenkamp S, Stang A, Grönemeyer D, Seibel R, Hirche H, et al. : Assessment of clinically silent atherosclerotic disease and established and novel risk factors for predicting myocardial infarction and cardiac death in healthy middle-aged subjects: Rationale and design of the Heinz Nixdorf RECALL Study. Risk Factors, Evaluation of Coronary Calcium and Lifestyle. Am Heart J 144: 212–218, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang XR, Zhang JJ, Xu XX, Wu YG: Prevalence of coronary artery calcification and its association with mortality, cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail 41: 244–256, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy SK, Cespedes A, Li D, Choi TY, Budoff MJ: Mild and moderate pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease is associated with increased coronary artery calcium. Vasc Health Risk Manag 7: 719–724, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Budoff MJ, Reilly MP, Yang W, Rosas SE, Rahman M, et al. ; CRIC Investigators : Coronary artery calcification and risk of cardiovascular disease and death among patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA Cardiol 2: 635–643, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, Jafar TH, Heerspink HJ, Mann JF, et al. : Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet 382: 339–352, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamarche MC, Hopman WM, Garland JS, White CA, Holden RM: Relationship of coronary artery calcification with renal function decline and mortality in predialysis chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 34: 1715–1722, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garland JS, Holden RM, Hopman WM, Gill SS, Nolan RL, Morton AR: Body mass index, coronary artery calcification, and kidney function decline in stage 3 to 5 chronic kidney disease patients. J Ren Nutr 23: 4–11, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dellegrottaglie S, Saran R, Gillespie B, Zhang X, Chung S, Finkelstein F, et al. : Prevalence and predictors of cardiovascular calcium in chronic kidney disease (from the Prospective Longitudinal RRI-CKD Study). Am J Cardiol 98: 571–576, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, et al. ; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration : Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 145: 247–254, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, et al. : Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in humans: A statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation 111: 697–716, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang E, Han M, Kim H, Park SK, Lee J, Hyun YY, et al. : Baseline general characteristics of the Korean chronic kidney disease: Report from the KoreaN Cohort Study for Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease (KNOW-CKD). J Korean Med Sci 32: 221–230, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) : KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 3: 19–62, 2013. Available at: https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf. Accessed June, 202225018975 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noordzij M, Leffondré K, van Stralen KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW, Jager KJ: When do we need competing risks methods for survival analysis in nephrology? Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2670–2677, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yun HR, Kim H, Park JT, Chang TI, Yoo TH, Kang SW, et al. ; Korean Cohort Study for Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease (KNOW-CKD) Investigators : Obesity, metabolic abnormality, and progression of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 72: 400–410, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenland P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Erbel R, Watson KE: Coronary calcium score and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 72: 434–447, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Handy CE, Desai CS, Dardari ZA, Al-Mallah MH, Miedema MD, Ouyang P, et al. : The association of coronary artery calcium with noncardiovascular disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 9: 568–576, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ketteler M, Schlieper G, Floege J: Calcification and cardiovascular health: New insights into an old phenomenon. Hypertension 47: 1027–1034, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oh KH, Park SK, Park HC, Chin HJ, Chae DW, Choi KH, et al. ; Representing KNOW-CKD Study Group : KNOW-CKD (KoreaN cohort study for Outcome in patients With Chronic Kidney Disease): Design and methods. BMC Nephrol 15: 80, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schurgin S, Rich S, Mazzone T: Increased prevalence of significant coronary artery calcification in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 24: 335–338, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harper E, Forde H, Davenport C, Rochfort KD, Smith D, Cummins PM: Vascular calcification in type-2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Integrative roles for OPG, RANKL and TRAIL. Vascul Pharmacol 82: 30–40, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miedema MD, Duprez DA, Misialek JR, Blaha MJ, Nasir K, Silverman MG, et al. : Use of coronary artery calcium testing to guide aspirin utilization for primary prevention: Estimates from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 7: 453–460, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ajufo E, Ayers CR, Vigen R, Joshi PH, Rohatgi A, de Lemos JA, et al. : Value of coronary artery calcium scanning in association with the net benefit of aspirin in primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiol 6: 179–187, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) : KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 7: 1–59, 2017. Available at: https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2017-KDIGO-CKD-MBD-GL-Update.pdf. Accessed June, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer SC, Di Micco L, Razavian M, Craig JC, Perkovic V, Pellegrini F, et al. : Effects of antiplatelet therapy on mortality and cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes in persons with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 156: 445–459, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Violi F, Targher G, Vestri A, Carnevale R, Averna M, Farcomeni A, et al. : Effect of aspirin on renal disease progression in patients with type 2 diabetes: A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. The renaL disEase progression by aspirin in diabetic pAtients (LEDA) trial. Rationale and study design. Am Heart J 189: 120–127, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiong J, He T, Yu Z, Yang K, Chen F, Cheng J, et al. : Antiplatelet therapy for the prevention of atherosclerosis in chronic kidney disease (ALTAS-CKD) patients: Study protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Trials 22: 37, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oh KH, Kang M, Kang E, Ryu H, Han SH, Yoo TH, et al. ; KNOW-CKD Study Investigators : The KNOW-CKD Study: What we have learned about chronic kidney diseases. Kidney Res Clin Pract 39: 121–135, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim CS, Bae EH, Ma SK, Han SH, Lee KB, Lee J, et al. ; KNOW-CKD Study Group : Chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder in Korean patients: A report from the KoreaN Cohort Study for Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease (KNOW-CKD). J Korean Med Sci 32: 240–248, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyun YY, Kim H, Oh YK, Oh KH, Ahn C, Sung SA, et al. : High fibroblast growth factor 23 is associated with coronary calcification in patients with high adiponectin: Analysis from the KoreaN cohort study for Outcome in patients With Chronic Kidney Disease (KNOW-CKD) study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 34: 123–129, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Devaraj S, Duncan-Staley C, Jialal I: Evaluation of a method for fibroblast growth factor-23: A novel biomarker of adverse outcomes in patients with renal disease. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 8: 477–482, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim YJ, Yong HS, Kim SM, Kim JA, Yang DH, Hong YJ; Korean Society of Radiology; Korean Society of Cardiology : Korean guidelines for the appropriate use of cardiac CT. Korean J Radiol 16: 251–285, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.