Abstract

The insulin/IGF signalling pathway impacts lifespan across distant taxa, by controlling the activity of nodal transcription factors. In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, the transcription regulators DAF-16/FOXO and SKN-1/Nrf function to promote longevity under conditions of low insulin/IGF signalling and stress. The activity and subcellular localization of both DAF-16 and SKN-1 is further modulated by specific posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination. Here, we show that ageing elicits a marked increase of SUMO levels in C. elegans. In turn, SUMO fine-tunes DAF-16 and SKN-1 activity in specific C. elegans somatic tissues, to enhance stress resistance. SUMOylation of DAF-16 modulates mitochondrial homeostasis by interfering with mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Our findings reveal that SUMO is an important determinant of lifespan, and provide novel insight, relevant to the complexity of the signalling mechanisms that influence gene expression to govern organismal survival in metazoans.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Organelles, Post-translational modifications, Ageing

Introduction

Organismal homeostasis is relentlessly challenged by various external and internal stressors. Over the course of life, homeostasis gradually declines and finally collapses, leading to death. Studies in organisms ranging from microbes to humans have culminated in the identification of multiple hallmarks of the ageing process and numerous regulatory factors that influence lifespan1,2. Amongst these, the insulin/IGF-1 pathway has a major role in lifespan determination3,4; and is evolutionarily conserved from worms to mammals5. In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, it entails the activation of insulin receptor DAF-2 (dauer formation abnormal), by insulin-like peptides. The activated receptor triggers a series of phosphorylation events in the cytoplasm, including the phosphorylation of the FOXO transcription factor, DAF-16. The phosphorylated form of DAF-16 is retained in the cytoplasm. Under stress conditions (heat shock, starvation, oxidative stress) DAF-16 is no longer phosphorylated and translocates to the nucleus, where it activates the transcription of genes responsible for development, longevity, re-wiring of metabolism, and stress responses6,7. Importantly, other stress responsive transcription factors such as SKN-1, function together with DAF-16. SKN-1 (skinhead) is the orthologue of the mammalian NRF2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) and has a main role in oxidative stress response8.

The functional decline of mitochondria during ageing is another major determinant of lifespan. The ageing process brings about the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, which exhibit increased ROS production, accrual of mitochondrial DNA, and less efficient ATP production1. In addition, mitochondrial dynamics is also altered over the course of lifespan9. The proper balance of mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial clearance by organelle-specific autophagy (mitophagy) is a prerequisite of healthy ageing. DAF-16 and SKN-1 are key regulators of these two processes10. The activity of these transcription factors is modulated by many targeted posttranslational protein modifications, including phosphorylation, methylation, and ubiquitination11–13. We sought to investigate whether other modes of posttranslational modification influence the activity of these nodal transcription factors, under normal and stress conditions.

SUMOylation, the attachment of a small ubiquitin like modifier (SUMO) to a target protein, is a posttranslational modification that plays pivotal roles in fundamental cellular processes including DNA damage responses, mitochondrial dynamics, development and senescence, among others14,15. In close analogy to ubiquitination, regulatory SUMOylation requires a heterodimeric E1 activating enzyme, an E2 conjugation enzyme, an E3 SUMO ligase and a SUMO protease. The C. elegans genome encodes a sole SUMO gene, smo-1, which makes it an expedient model organism to dissect its diverse functions. SUMOylation has been mainly studied in the context of development in C. elegans, and has been implicated in embryonic, vulval and muscle development, and in DNA damage responses16–27. Recently, SUMOylation of a specific RNA binding protein (CAR-1) in the germline has been linked to organismal ageing28. Notably, the level of SUMO1 modified proteins has been shown to progressively increase during ageing in blood plasma and cortical lysates of mice29. However, a causative relationship between SUMOylation and ageing has not been established.

Here, we uncover a direct link between SUMO and the regulation of ageing, in C. elegans. Perturbation of SUMO levels causes alterations in lifespan and mitochondrial homeostasis in a DAF-16/FOXO and SKN-1/NRF2 dependent manner. Reduced smo-1 expression leads to shortened lifespan, coupled with impaired mitochondrial ATP and ROS production, mitophagy defects and over-activation of stress response genes. In addition, we demonstrate for the first time that DAF-16 is SUMOylated, and that this modification represses the transcriptional activity of DAF-16.

Materials and methods

C. elegans strains and genetics

We followed standard procedures for maintenance of C. elegans strains and transgenic lines30. Animals were grown at 20 °C unless noted otherwise. The following strains were used for this study: N2: wild type Bristol isolate, CB1370: daf-2(e1370)III, MQ887: isp-1(qm150)IV, CF1038: daf-16(mu86)I, KX15: ife-2(ok306)X, SJ4143: N2;Is[pges-1mtGFP], CL2166: N2;Is[pgst-4GFP], CF1553: N2;Is[psod-3GFP], TJ356: N2;Is[pdaf-16DAF-16a/b::GFP;rol-6(su1006)], FGP14: unc-119(ed3); fgpIs35[unc-119(+);psmo-1::6xHis::smo-1::smo-1 3′ UTR], VP303: rde-1(ne219)V;kbIs7[pnhx-2::rde-1;rol-6(su1006)], NR350: rde-1(ne219)V; kzIs20[phlh-1::rde-1;psur-5::NLS::GFP], NR222: rde-1(ne219)V;kzIs9[plin-26::NLS::GFP;plin-26::rde-1;rol-6(su1006)], TU3401: sid-1(pk3321)V;uIs69[pmyo-2::mCherry;punc-119::sid-1], NL2099: rrf-3(pk1426)II, JRIS1: N2; Is[prpl-17HyPer]..

Molecular cloning

To create a psmo-1DsRed::SMO-1 construct, we utilized the pPD95.77(DsRed) construct, previously generated in the lab. Briefly, GFP was excised from pPD95.77 (GFP) vector using the AgeI/EcoRI restriction enzymes, and was replaced with the fragment coding DsRed, isolated from pcol-12DsRed31. We amplified the smo-1 ORF from C. elegans genomic DNA, using the following primer pair: 5′-GAATTCCAACATGGCCGATGATGCAG-3′ and 5′-GGATCCCGTTTATAGCGGGAGTCTC-3′ and the 560 bp product was first subcloned into pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). Using the restriction enzyme EcoRI, the fragment was excised and inserted into pPD95.77 (DsRed) and was sequenced to check for possible mutations and orientation. The correct construct was introduced to unc-119(ed3) worms, together with pRH2132, using biolistic transformation. To generate the pvha-6SMO-1 construct, we amplified the smo-1 ORF from C. elegans genomic DNA, using the following primer pair: 5′-GTTTCAGAGACTCCCGCTATAAAC-3′ and 5′-GCTAGCCGAAGAGTTTATTTGTAAG-3′ and the 570 bp product was subcloned into pCRII-TOPO vector. Using the restriction enzymes BamHI/NheI, the fragment was inserted in pPD96.52 vector, containing the myo-3 promoter. The promoter was removed, using the HindIII/XbaI restriction enzymes and the 950 bp coding sequence of vha-6 promoter was inserted from pCRII-TOPO. To amplify the vha-6 promoter from C. elegans genomic DNA, we used the following primer pair: 5′-GAGAAGATGTGATGAGATGGAGAGAAAG-3′ and 5′-TGAGCACTTTACAGTTCTTGTTGATTTG-3′. The construct, together with the pRH21 plasmid, was introduced to unc-119(ed3) worms, using biolistic transformation. To generate the prab-3SMO-1 construct, we amplified the smo-1 ORF from C. elegans genomic DNA, using the following primer pair: 5′-CCCGGGGTTTCAGAGACTC-3′ and 5′-GGTACCCGAAGAGTTTATTTGTAAG-3′ and the 580 bp product was subcloned into pCRII-TOPO vector. We inserted the Xma/KpnI fragment in pPD95.77, containing the rab-3 promoter. The construct and the pRH21 plasmid were introduced to unc-119(ed3) worms, using biolistic transformation. For the generation of smo-1, ubc-9 , ulp-1, ulp-2, ulp-4 and ulp-5 RNAi construct, the following primer pairs were used: 5′-TAAACGATGGCCGATGATGC-3′ and 5′-GGATCCCGAAAGAGTTTATTTGTAAG-3′, 5′-ATGTCGGGAATTGCTGCAGG-3′ and 5′-GTCCAGAAGCAAATGCTCGAGTAG-3′, 5′-CCACAGTTGTTACAGAACAAG-3′ and 5′-GGATCCCACATTAGTTTCTCTGCTTC-3′, 5′-ATGAGTGATTCAACTCAAATGGAGG-3′ and 5′-CATACAGCAGTTGCCACAAACG-3′, 5′-ATGGAAGTGTCAACGTCTTACTGTACG-3′ and 5′-GATTTTTGCTGTCTCCAGGAGAAG-3′, 5′-ATGCCTCATCCTAAGCTCACTCC-3′ and 5′-GCCTGGTTCATTCAAAAAAATACAG-3′, respectively. The resulted fragments were cloned into the vector pL4440 and the constructs were transformed into HT115 (DE3) Escherichia coli strain, which is defective for RNase III. Bacteria carrying the pL4440 empty vector alone were used for control experiments. RNAi constructs against daf-2, eat-3, daf-16, skn-1, drp-1, fzo-1 have been described previously10,33. Double RNAi against skn-1 and smo-1 was constructed by digesting the skn-1(RNAi) and smo-1(RNAi) plasmids with BamHI restriction enzyme and ligating the smo-1 fragment (~ 1000 bp) into skn-1(RNAi) plasmid, treated with Alkaline Phosphatase, Calf Intestinal (CIP, New England Biolabs).

Epifluorescence and confocal microscopy

Transgenic worms were placed in a drop of 10 mM levamisole on a microscope slide and sealed with a cover slip. Images were taken with a Zeiss AxioImager Z2 epifluorescence microscope. At least 25 worms were imaged and quantified per condition; each experiment was repeated at least three times. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured using the software Image J. The nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio of pdaf-16DAF-16::GFP was measured as follows: we measured the mean fluorescence intensity of a nucleus and the intensity of the same selection area of the corresponding cytoplasm. These two numbers were divided to get the ratio. For confocal microscopy, animals were immobilized on a 5% agarose pad, in a 5 μl drop of Nanobeads (Nanobeads NIST Traceable Particle Size Standard 100 nm, Polysciences). Images were taken with an LSM710 Zeiss confocal microscope, Axio-observer Z1.

Western blot analysis

For the analysis of SUMO conjugated proteins during ageing, synchronized animals were collected in M9 buffer and after a short spin, the buffer was exchanged to the lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH: 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 30 mM NEM) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete mini protease inhibitors cocktail tablets—ROCHE) just before use. Animals were frozen at − 80 °C and then boiled at 95 °C together with 1X Laemmli sample buffer (70 mM SDS, 1.5 mM bromophenol blue, 0.8% glycerol, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH: 6.8, 100 mM DTT). The lysates were spun down at 4 °C, then loaded and separated by 4–12% Bis–Tris gel and transferred to PVDF membrane (Amersham-GE Healthcare). The membrane was blocked using 5% non-fat milk for 1 h and then incubated overnight with anti-SUMO antibody34 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) Cat# SUMO 6F2, RRID:AB_2618393, 1:250) and with anti-α-tubulin antibody (DSHB Cat# AA4.3, RRID:AB_579793, 1:5000) in 5% non-fat milk at 4 °C. The next day the membrane was washed with 1XPBS-T (0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After washes with 1XPBS-T, the membrane was developed by chemiluminescence (Supersignal chemiluminescent substrate pico and femto, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

For the analysis of SUMO conjugated proteins upon smo-1(RNAi) and SMO-1 overexpression (FGP14 strain), animals were washed and collected from two plates in M9 buffer with 0.1% Triton-X 100. Animals were washed one time with M9 buffer with 0.1% Triton-X 100 and transferred to a new tube. 200 μl of 40% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (Sigma-Aldrich) and 300 μl glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to each sample. Samples were lysed by using a Beadbeater (Biospec), for 3 min (1 min on–1 min off) in a cold room. Lysates were transferred to a new tube and the beads were washed with 5% TCA and mixed with the lysates. Samples then were centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 rpm at 4 °C. The pellet was washed three times with 500 μl chilled acetone. Pellets were dried at room temperature and resuspended in 100 μl 1X Sample Reducing Agent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Following a 5 min incubation at 70 °C, samples were sonicated 2× for 10 s (12% amplitude). Samples were incubated again at 70 °C and then centrifuged for 10 min at 11,000 rpm. Samples were transferred to a new tube and loaded onto a 4–12% Bis–Tris gel for separation, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham-GE Healthcare). The membrane was blocked in a blocking solution (Invitrogen) for 1 h and then incubated overnight with anti-SUMO antibody (sheep)35 (1:1000) and with anti-α-tubulin antibody (DSHB Cat# AA4.3, RRID:AB_579793, 1:5000) in 3% BSA at 4 °C. The next day the membrane was washed with 1XPBS-T (0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with AlexaFluor 647 secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After washes with 1XPBS-T, the membrane was analyzed with Amersham Typhoon Biomolecular Imager (GE Healthcare).

Mitochondria isolation

Age matched animals were collected in M9 buffer, and incubated at 4 °C with rotation in the presence of 10 mM DTT. To remove the DTT from the sample, three washes were performed with M9. Worms were homogenized in incubation buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH:7.4, 210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM PMSF, cOmplete mini protease inhibitors cocktail (ROCHE)] with 100 strokes in a 3 ml Potter–Elvehjem homogenizer with PTFE pestle and glass tube (Sigma-Aldrich). The lysate was centrifuged at 200g for 1 min. The pellet was subjected to another round of homogenization. The lysate was combined with the supernatant from the previous centrifugation step, and they were centrifuged together for 1 min at 200g. The supernatant was centrifuged again at 12,000g for 5 min. We kept the supernatant as the cytoplasmic fraction and resuspended the pellet/mitochondrial fraction in incubation buffer. Samples were analysed on 4–12% SDS-PAGE gradient gels with anti-SUMO (DSHB Cat# SUMO 6F2, RRID:AB_2618393), anti-MTCO1 (Abcam [1D6E1A8] (ab14705)) and anti-α-tubulin (DSHB Cat# AA4.3, RRID:AB_579793).

DAF-16 and SKN-1 purification

We codon optimized the sequence of isoform “a” of DAF-16 (UniProt number: O16850) and isoform “c” of SKN-1 (UniProt number: P34707) and inserted into a vector suitable for bacterial expression, pHis-TEV-30a36. This vector also contains an N terminal 6xHis-MBP tag and a TEV cleavage site. The construct was transformed to BL21 Rosetta E. coli strain for protein expression. Bacterial cultures were grown at 37 °C until OD600 = 0.8, then cooled down and induced with 1 mM IPTG at 20 °C for 4 h for DAF-16 expression and with 0.1 mM IPTG at 37 °C for 4 h for SKN-1 expression. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation (4500 rpm, 30 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in 50 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.5 mM TCEP and cOmplete mini protease inhibitors cocktail tablets – ROCHE. Cells were lysed by sonication (Digital Sonifier, Branson) for 5X 20 s pulses at 50% amplitude with 20 s cooling period between pulses. Cell lysate was centrifuged (15,000 rpm, 45 min, 4 °C) to clear the sample from any insoluble material and supernatant was loaded onto a 2 ml Ni–NTA column (Qiagen) pre-equilibrated with lysis buffer. After sample binding, the column was washed with ten column volume of lysis buffer and with ten column volume of lysis buffer containing 30 mM imidazole. The protein was eluted from the column with elution buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 150 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM TCEP). DAF-16 was further purified by size exclusion chromatography with Superose 6 Increase 10/300 column (GE Healthcare). Purified and concentrated protein was aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C.

In vitro SUMOylation assays

Conjugation assays contained 50 mM Tris–HCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 5 μg SUMO, 0.5 μg SUMO-Alexa Fluor 680, 60 ng SAE1/SAE2 (SUMO E1), 5 or 20 ng UBC-9, 10, 50 or 100 ng GEI-17 and 5 μg DAF-16, SKN-1 or MBP. Reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 4 h and they were run parallel on 4–12% Bis–Tris (better visualization of free SUMO) and 3–8% Tris–Acetate gels (better visualization of SUMO modified proteins). Gels were analyzed by Coomassie staining and Amersham Typhoon Biomolecular Imager (GE Healthcare)35.

Mitochondrial imaging

For TMRE (tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester) (Sigma) staining, age-matched animals were placed overnight on an RNAi plate containing 150 nM TMRE and the next morning placed in a 10 mM levamisole drop on a microscope slide, sealed with a cover slip. Images were taken with a Zeiss AxioImager Z2 epifluorescence microscope. For mitochondrial ROS staining, synchronized animals were placed on RNAi plates containing 150 nM MitoTracker Red CMXROS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight and the next morning were mounted on microscope slides in a 10 mM levamisole drop, sealed with a cover slip to assess mitochondrial ROS production. Images were taken with a Zeiss AxioImager Z2 epifluorescence microscope. Images were quantified using the software Image J. For paraquat treated TMRE staining, age-matched animals were placed on RNAi plates containing 4 mM paraquat for 1 day, and the next day were transferred to a fresh RNAi plate containing 4 mM paraquat and 150 nM TMRE. The next morning the animals were placed on microscope slides in a 10 mM levamisole drop, sealed with a cover slip. Images were taken with a Zeiss AxioImager Z2 epifluorescence microscope. Images were quantified using the software Image J. For monitoring mitophagy we used the previously described mitochondrial targeted Rosella biosensor in body wall muscle cells of the animals10, with a minor modification. We created a new transgenic line with biolistic transformation and fed these animals with the test RNAi constructs. Animals were mounted on 5% agarose pads in a 10 mM levamisole drop and sealed with a cover slip. Images were taken with an Invitrogen EVOS FL Auto 2 Cell Imaging System. Images were quantified using the software Image J.

Messenger RNA quantification

Total RNA was extracted from worms, using Trizol (Sigma). cDNA was synthesized using the iScript kit (BioRad). Quantitative Real Time PCR was performed using a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR system, and was repeated three times. The following primer pairs were used to quantify the expression of genes: for ges-1: 5′-TCGCCAAGAGGTATGCTTCACAAG-3′ and 5′-TGCTGCTCCTGCACTGTATCCC-3′, for gst-4: 5′-GGCAAGAAAATTTGGACTC-3′ and 5′-GCCAAGAAATCATCACGGGC-3′, for sod-3: 5′-ATTGCTCTCCAACCAGCGC-3′ and 5′-GGAACCGAAGTCGCGCTTAA-3′, for smo-1: 5′-AAGATCAAGGTCGTTGGACAGGAC-3′ and 5′-CTAGAATCCGCCCAGCTGCT-3′.

ATP measurements

To quantify intracellular ATP levels, we followed the protocol described here37. In short, 100 age matched animals were collected in 50 µl of M9 buffer and frozen at − 80 °C. Frozen worms were boiled at 95 °C for 15 min. After a 10 min centrifugation step at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C, the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and diluted tenfold before measurement. ATP content was determined by using the Roche ATP bioluminescent assay kit HSII (Roche Applied Science) and a TD-20/20 luminometer (TurnerDesigns). ATP levels were normalized to total protein content.

Oxygen consumption rate measurement

To determine oxygen consumption rates, we followed a previously described protocol38. In short, 4-day-old adult animals were collected in 1 ml M9, and transferred to the chamber of Oxygraph (Hansatech Instruments). Measurements were performed for 15 min at 20 °C. The oxygen consumption rate was obtained by the slope of the straight portion of the plot. The animals were recovered after measurement and were subjected to sonication and protein determination. The oxygen consumption rates were normalized to total protein content.

Mitochondrial DNA quantification

mtDNA was quantified using quantitative real time PCR as described previously39. 50 worms were collected per condition, lysed and diluted tenfold before performing the PCR reaction. The following primer set was used for mtDNA (mito-1): 5′-GTTTATGCTGCTGTAGCGTG-3′ and 5′-CTGTTAAAGCAAGTGGACGAG-3′. The results were normalized to genomic DNA using the following primers specific for ama-1: 5′-TGGAACTCTGGAGTCACACC-3′ and 5′-CATCCTCCTTCATTGAACGG-3′. Quantitative PCR was performed using a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR system, and was repeated three times.

Lifespan analysis

Experiments were carried out at 20 °C, unless noted otherwise. Animals were synchronized by placing 7–8 gravid adults on control RNAi plates for overnight egg laying and they were removed the next morning. L4 larvae were placed on experimental plates (containing 2 mM IPTG and seeded with HT115 (DE3) bacteria comprising the control vector (pL4440) or the test RNAi construct) and they were transferred to a fresh plate every 2–3 days. Animals were scored for survival with movement provoking touch every second day. Those who crawled out of the plate or died due to internal egg-hatching were considered censored and incorporated into the dataset as such. Each lifespan assay was repeated at least two times and figures represent typical assays. Lifespan assays on NAC (N-acetyl cysteine) plates (10 mM final concentration) were performed only one time. Statistical analysis was performed using the Prism software package (version 7; GraphPad Software; https://www.graphpad.com), and the product-limit method of Kaplan and Meier.

Survival assays

For oxidative stress assays we grew synchronized animals until day 6 of adulthood on control or smo-1(RNAi) plates. At day 6 animals were transferred to control or smo-1(RNAi) plates containing paraquat (methyl viologen dichloride hydrate, Sigma) in 2 mM final concentration. Additionally, bacteria were killed with UV before adding paraquat on the plates in order to prevent interference arising from bacterial metabolism.

For acute heat stress survival the animals were grown until day 4 of adulthood on control or smo-1(RNAi) plates at 20 °C. At day 4 of adulthood, animals were subjected to 37 °C for 2 h and then placed back to 20 °C. In both stress conditions animals were scored for survival with movement provoking touch every day. Those who crawled out of the plate or died due to internal egg-hatching were considered censored and incorporated into the dataset as such. Each stress survival assay was repeated at least two times and figures represent typical assays. Statistical analysis was performed using the Prism software package (version 7; GraphPad Software; https://www.graphpad.com), and the product-limit method of Kaplan and Meier.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using the Prism software package (version 7; GraphPad Software; https://www.graphpad.com) and the Microsoft Office 2010 Excel software package (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Mean values were compared using unpaired t-tests or one-way ANOVA.

Results

SUMOylation modulates ageing in C. elegans

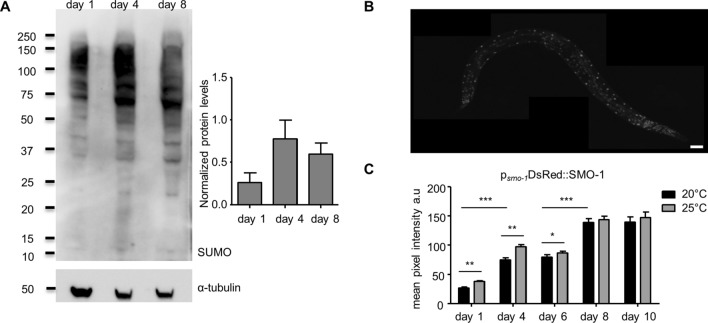

To examine SUMOylation over the course of ageing in C. elegans, we performed Western blot analysis, using age matched, wild type animals. We find that the amount of SUMO conjugated proteins peaks at day 4 of adulthood in C. elegans (Fig. 1A). To assess SUMO expression, we generated transgenic animals, expressing a full-length, DsRed-tagged SMO-1 reporter fusion (psmo-1DsRed::SMO-1; Fig. 1B). We observed nuclear localization of SUMO in all tissues (e.g. neurons, seam cells, intestine and muscles; Fig. 1B). SMO-1 expression increases during ageing and upon a temperature shift to 25 °C (Fig. 1C). Thus, SMO-1 expression is progressively increasing with age and under mild thermal stress, in C. elegans.

Figure 1.

SUMO levels are increasing during ageing. (A) Western blot analysis of SUMO protein levels in day 1, 4 and 8 wild type lysates (n = 500 worms/sample, N = 4, day 1 vs day 4: p = 0.103, day 1 vs day 8: p = 0.119). Protein levels were normalized to α-tubulin. Error bars, S.E.M. (B) psmo-1DsRed::SMO-1 expression pattern, scale bar: 40 μm. The image was acquired using a × 20 objective lens. (C) The expression of psmo-1DsRed::SMO-1 is increasing during ageing and when the animals are grown at 25 °C. (n = 50, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, unpaired t-test). Error bars, S.E.M.

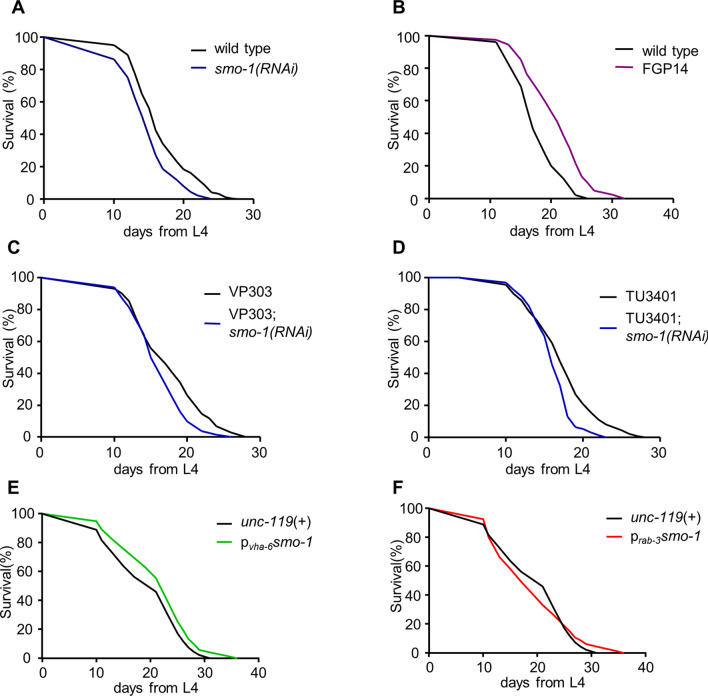

SUMOylation is essential during development40. Consequently, mutation of smo-1 causes embryonic lethality41,42. To examine the physiological significance of SUMO accumulation during ageing, we reduced smo-1 expression post-developmentally, at the end of the L4 larval stage by RNAi (Fig. S1A). We observed significant reduction of animal lifespan (Fig. 2A). By contrast, downregulation of the 4 SUMO proteases (ubiquitin-like proteases), encoded in the C. elegans genome (ulp-1-2, ulp-4-5), did not alter the lifespan of wild type animals (Fig. S1B,C), under normal conditions. However, reduced expression of ulp-1 resulted in a prolonged lifespan at 25 °C (Fig. S1D). Importantly, smo-1 overexpression extended lifespan (FGP14 strain, Pelisch and Hay, 2016; psmo-1::6xHis::smo-1::smo-1 3′ UTR; Figs. S1A, 2B). These findings indicate that SUMO is a modulator of ageing in C. elegans.

Figure 2.

SUMO modulates lifespan through the intestine and nervous system. (A, B) Knockdown of smo-1 shortens the lifespan of wild type animals, while overexpression of smo-1 extends lifespan. (C) Intestine specific smo-1(RNAi) shortens lifespan. (D) Neuron specific smo-1(RNAi) reduces lifespan. (E) Intestine specific smo-1 overexpression extends lifespan. (F) Neuron specific smo-1 overexpression does not have a significant effect on lifespan. Lifespan assays were carried out at 20 °C. Lifespan values are given in Table S1.

Previous studies have established the prominent contribution of specific tissues in the control of the ageing process43. To examine whether SUMO promotes longevity in a tissue specific manner, we targeted smo-1 expression in different tissues by RNAi. We utilized transgenic strains carrying a mutation in rde-1 gene (RNAi defective), which encodes an Argonaute protein family member that is required for RNA interference44. A wild type version of rde-1 is then re-introduced to the animals in a tissue specific manner, restoring RNAi capacity in that tissue. Using this approach, we assessed the effects of SUMO downregulation in the intestine (VP303 strain), hypodermis (NR222 strain) and muscles (NR350 strain). Only intestine specific smo-1(RNAi) resulted in shorter lifespan, while knockdown of smo-1 in hypodermal and muscle tissues had no effect (Fig. 2C, Fig.S1E,F). We also investigated the consequences of neuron-specific SUMO deficiency. The nervous system of C. elegans is mostly resistant to RNAi, but specific neurons (amphids and phasmids) are susceptible45. To probe neuron specific SUMO depletion, we used a strain (TU3401), which carries a mutation in sid-1 (systemic RNA interference defective), a gene that encodes a transmembrane channel for dsRNA, required for systemic RNA interference46. To render neurons susceptible to RNAi, a sid-1 transgene is introduced, driven by a pan-neuronal promoter, unc-11947. Similarly to the intestine, reduction of smo-1 expression, specifically in neurons, resulted in shorter lifespan (Fig. 2D). Importantly, overexpression of smo-1 specifically in the intestine (pvha-6smo-1), led to an extended lifespan (Fig. 2E). On the contrary, neuron-specific smo-1 overexpression (prab-3smo-1) did not have any significant effect on the lifespan of the animals (Fig. 2F). This result suggests the importance of balanced SUMO levels in the nervous system. Taken together, these findings indicate that SUMO influences C. elegans lifespan through the intestine and the nervous system.

SUMO regulates the transcriptional activity of SKN-1 and DAF-16

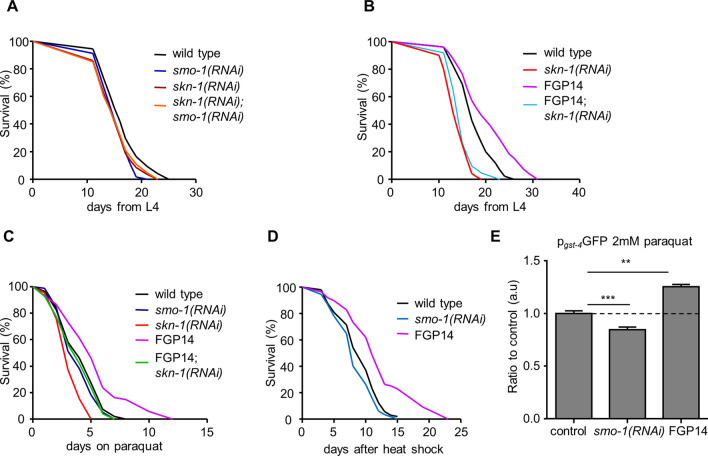

To gain insight relevant to the role of SUMOylation in the regulation of ageing, we examined the effects of SUMO depletion in the context of well-characterized signalling pathways that modulate lifespan in C. elegans5. HSF-1, SKN-1 and DAF-16 are key stress response transcription factors, promoting longevity under conditions of heat shock, mild oxidative stress and low insulin/IGF1 signalling8. Considering, that HSF-1 has been shown to have the potential to be modified by SUMO, both in mammals48 and in C. elegans49, we focused our studies on SKN-1 and DAF-16. We find that skn-1(RNAi);smo-1(RNAi) animals display shorter lifespan, similar to animals subjected only to skn-1 RNAi (Fig. 3A). Importantly, SKN-1 depletion annulled lifespan extension caused by SMO-1 overexpression (Fig. 3B). Thus, SKN-1 mediates the pro-longevity effects of SUMO. Given that the mammalian orthologue of SKN-1, NRF2 is a target for SUMOylation50,51, we examined whether SKN-1 is also modified by SUMO conjugation. Detection of SUMO modification in vivo poses multiple challenges (low expression of SKN-1 under normal conditions, low SUMOylation rates of total protein content), and we were unable to observe it in our Western blots (data not shown). To this end, we performed in vitro SUMOylation assays with bacterially expressed 6xHis-MBP tagged and purified SKN-1. We found that SKN-1 is not an optimal SUMO target in vitro (Fig. S2A).

Figure 3.

SKN-1 mediates the lifespan influencing effect of SUMO. (A) smo-1(RNAi) does not further reduce the short lifespan of skn-1(RNAi) treated animals. (B) skn-1(RNAi) shortens the lifespan of the FGP14 strain to the level seen in wild type animals subjected to skn-1 RNAi. (C) SMO-1 overexpressing animals survive longer on 2 mM paraquat, while loss of smo-1 does not change the survival compared to wild type animals. skn-1(RNAi) treated animals have a reduced survival rate on paraquat. (D) Heat shock did not change the survival of smo-1(RNAi) fed animals while worms overexpressing SMO-1 displayed increased survival rates. The percentage of animals remaining alive is plotted against age. (E) FGP14 animals are mounting a stronger oxidative stress response in day 2 animals compared to control, measured by pgst-4GFP expression. smo-1(RNAi) reduced the responsiveness of animals to paraquat. (n = 40, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 unpaired t-test). Error bars, S.E.M. Lifespan assays were carried out at 20 °C. Lifespan values are given in Table S1.

To further investigate the role of SKN-1 in mediating the effects of SUMO on lifespan, we subjected animals to oxidative stress which activates SKN-152. We exposed 6 day old wild type, FGP14 and smo-1(RNAi) treated animals to 2 mM paraquat, an inducer of oxidative stress. As expected, skn-1(RNAi) treated animals were sensitive to oxidative stress (Fig. 3C). Notably, smo-1 overexpressing animals were resistant to oxidative stress, while reduction in smo-1 expression did not alter survival on paraquat (Fig. 3C). We also assayed heat stress resistance upon perturbation of SUMO levels. Similarly to oxidative stress, smo-1 overexpression increased survival of day 4 animals to acute (2 h) heat shock at 37 °C, whereas, SUMO depletion did not affect heat stress resistance (Fig. 3D). Next, we monitored the expression of gst-4, a SKN-1 target gene encoding glutathione S-transferase, levels in day 2 animals on 2 mM paraquat. Using a pgst-4GFP reporter fusion, we found that knockdown of smo-1 reduced the expression of gst-4, while, overexpression of smo-1 further increased gst-4 expression (Fig. 3E). Therefore, under stress conditions, increase of SUMO levels enhances stress resistance by potentiating expression of stress response genes, while depletion of SUMO compromises survival under stress by reducing the capacity to fully mount a response.

Interestingly, under normal conditions, smo-1 knockdown transiently increased gst-4 expression during adulthood in day 4 animals, while there was no observable difference by day 8 (Fig. S2B,C). By contrast, gst-4 expression was not altered upon smo-1 overexpression during adulthood (day 4 or day 8 animals; Fig. S2B,C). The mRNA levels of gst-4 mirrored the changes observed with the pgst-4GFP reporter fusion (Fig. S2D). We find that SKN-1 becomes activated in the absence of the FOXO transcription factor DAF-16 that mediates insulin/IGF1 signalling, in day 4 of adulthood, both in wild type and smo-1 overexpressing animals (Fig. S2B). SKN-1 activation is diminished by day 8 (Fig. S2C). Hence, although SKN-1 is likely not modified by SUMO in vivo, both are required for normal lifespan. Reduction of SUMO levels triggers activation of SKN-1, while SUMO abundance protects against stress and promotes longevity.

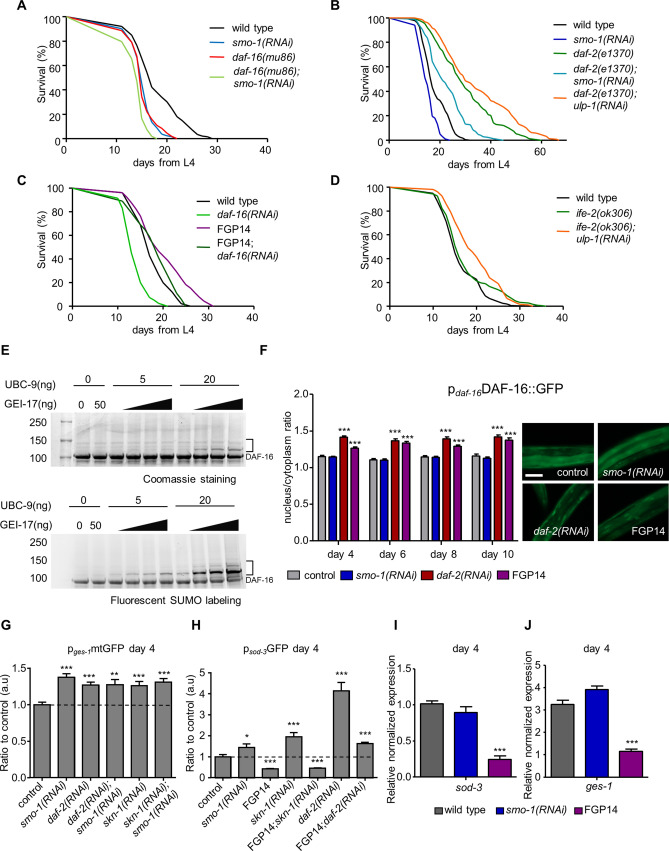

In addition to SKN-1, DAF-16 also promotes stress tolerance and longevity6. We asked whether SUMO exerts its effects on animal ageing by modulating DAF-16 activity. DAF-16 is activated in long-lived C. elegans mutants, carrying lesions in the insulin/IGF1 receptor DAF-2. We find that smo-1 knockdown shortened the lifespan of DAF-2 deficient animals (Fig. 4A,B). Furthermore, downregulation of daf-16 abolished lifespan extension caused by smo-1 overexpression (Fig. 4C). Notably, under lifespan-extending conditions, where DAF-16 is activated (in daf-2(e1370) mutants), or protein synthesis is reduced (in ife-2(ok306) mutants), downregulation of the SUMO protease ulp-1 extends lifespan (Fig. 4B,D). These findings indicate that DAF-16 is, in part, mediating the effects of SUMO on lifespan. Thus, we investigated whether DAF-16 is a target for SUMOylation.

Figure 4.

DAF-16 is SUMO modified and SUMO inhibits the transcriptional activity of DAF-16. (A) smo-1(RNAi) shortens the lifespan of daf-16(mu86) animals. (B) The long lifespan of daf-2(e1370) animals is reduced by smo-1(RNAi) and extended by ulp-1(RNAi). (C) daf-16(RNAi) partly shortens the long lifespan of FGP14 strain. (D) ife-2(ok306) animals treated with ulp-1 RNAi have a longer lifespan. (E) In vitro DAF-16 SUMOylation assay. Top image shows Coomassie staining, bottom image shows fluorescently labelled SUMO with Alexa-Fluor 680. Brackets indicate the SUMO modified form of DAF-16. (F) Nuclear localization of pdaf-16DAF-16::GFP in control, smo-1(RNAi) and smo-1 overexpressing background (FGP14), daf-2(RNAi) was used as a positive control, scale bar: 50 μm. Images were acquired using × 40 objective lens (n = 50, ***p < 0.001, unpaired t-test). (G) pges-1mtGFP expression is elevated upon smo-1(RNAi) in wild type, daf-2(RNAi) and skn-1(RNAi) background in day 4 animals (n = 100, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, unpaired t-test). (H) psod-3GFP is increased upon knockdown of smo-1, skn-1 or daf-2. Overexpression of smo-1 reduces the expression level of psod-3GFP in day 4 animals (n = 100, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, unpaired t-test). (I, J). The mRNA levels of sod-3 and ges-1 are reduced in day 4 animals in the smo-1 overexpressing strain (***p < 0.001, unpaired t-test). Error bars, S.E.M. Lifespan assays were carried out at 20 °C. Lifespan values are given in Table S1.

We conducted in vitro SUMOylation assays with purified, bacterially expressed and 6xHis-MBP tagged DAF-16. We detected SUMO conjugation to DAF-16 (Fig. 4E top panel, Fig. S3A). To increase the sensitivity of our assay, we added fluorescently labelled SUMO (SUMO-AlexaFluor 680)35, which facilitated detection of the SUMO-modified form of DAF-16 (Fig. 4E, bottom panel). We also tested the capacity of the MBP tag to undergo SUMOylation. We found that MBP is not a SUMO target (Fig. S3B). Therefore, DAF-16 is a bona fide SUMOylation target.

Under normal conditions, the activity of DAF-16 is repressed by cytoplasmic confinement and degradation53. To determine whether changes in SUMO levels modulate DAF-16 activity, we monitored the subcellular localization of the protein by using a full length pdaf-16DAF-16::GFP reporter fusion. Downregulation of smo-1 did not alter the nuclear/cytoplasm ratio of DAF-16, during adulthood (Fig. 4F). By contrast, smo-1 overexpression triggered nuclear localization of DAF-16, to an extent similar to that observed in DAF-2 deficient animals (Fig. 4F). Notably, while SUMO depletion increased daf-16 expression, overexpression of smo-1 reduced daf-16 expression (Fig. S3C). Therefore, excess SUMO drives DAF-16 nuclear accumulation. However, subcellular partitioning alone is not enough to predict DAF-16 activity54. To gauge the effect of SUMO on the transcriptional activity of DAF-16, we assayed the expression of two typical DAF-16 target genes, ges-1 (abnormal gut esterase), a gut specific type B carboxylesterase, and sod-3 (superoxide dismutase), an iron/manganese superoxide dismutase. By using pges-1mtGFP and psod-3GFP reporter fusions, we found that DAF-16 activity increases in day 4 smo-1(RNAi) animals (Fig. 4G,H). This increase persists in older animals (day 8 for pges-1mtGFP and day 6 for psod-3GFP; Fig. S3D,E). Overexpression of smo-1 reduced DAF-16 activity (Fig. 4H,J, Fig. S3E). Notably, knockdown of skn-1 also activated DAF-16 in both wild type and smo-1 overexpressing animals (Fig. 4G,H, Fig. S3D,E), indicating a compensatory link between DAF-16 and SKN-1.

Since SUMOylation has been implicated in chromatin remodelling55, we considered whether smo-1 overexpression decreased transcription of DAF-16 target genes by inducing chromatin condensation. We found that knockdown of daf-2 increased sod-3 expression in smo-1 overexpressing animals, albeit to a lesser extent, compared to wild type controls (Fig. 3H, Fig. S3E). Taken together, these findings indicate that SUMO represses the transcriptional activity of DAF-16.

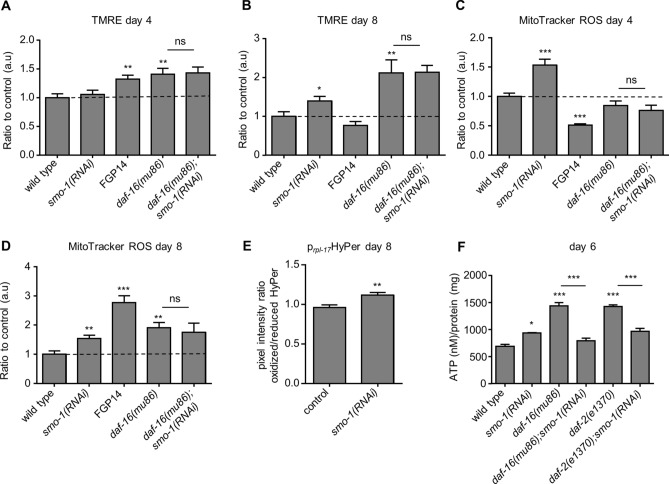

SUMO facilitates mitochondrial homeostasis

Mitochondrial metabolism is an important determinant of ageing across diverse organisms. We found that SUMOylation levels increase not just in whole worm lysates (Fig. 1A), but also in the mitochondrial fraction (Fig. S4A). To examine whether SUMO impacts lifespan by altering mitochondrial function, we utilized the dye, TMRE (tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester), which stains mitochondria according to their membrane potential. Wild type animals display reduced mitochondrial membrane potential during ageing1. Nevertheless, knockdown of smo-1 alleviated age-associated mitochondrial membrane potential decline (Fig. 5A,B). Moreover, animals overexpressing smo-1 displayed increased TMRE staining early in adulthood (Fig. 5A,B).

Figure 5.

SUMO changes the mitochondrial homeostasis. (A, B) TMRE staining declines during ageing in wild type but not smo-1(RNAi) treated animals, and this change is DAF-16 dependent (n = 100, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, unpaired t-test). (C, D) Mitochondrial ROS production, measured by MitoTracker ROS, is increased when we knockdown smo-1 and this effect is also DAF-16 dependent (n = 75, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, unpaired t-test). (E) H2O2 levels are increased in smo-1(RNAi) background, measured by the H2O2 biosensor, HyPer (n = 30, **p < 0.01, unpaired t-test). (F) ATP production is increased upon knockdown of smo-1 in day 6 wild type animals (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, unpaired t-test). Error bars, S.E.M.

Both DAF-16 and SKN-1 are key regulators of the mitochondrial homeostasis10,56. We find that knockdown of smo-1 in genetic backgrounds where DAF-16 is activated, such as isp-1(qm150), skn-1(RNAi), and daf-2(e1370) ameliorated mitochondrial membrane potential decline (Fig. S4B,C). Interestingly, mitochondrial membrane potential is elevated in DAF-16 deficient animals and does not increase further upon smo-1 downregulation (Fig. 5A,B). We also measured mitochondrial ROS production, using the MitoTracker ROS dye. Consistent with the TMRE data; smo-1 downregulation altered ROS production in all genetic backgrounds tested, except in DAF-16 deficient animals (Fig. 5C,D and S4D,E). Overexpression of smo-1 increased ROS production during ageing (Fig. 5D). Treatment with the antioxidant NAC (N-acetyl cysteine), diminished the extended lifespan of smo-1 overexpressing animals (Fig. S4F). Additionally, we utilized the prpl-17HyPer strain57 to determine H2O2 levels in animals treated with RNAi against smo-1. Similarly to MitoTracker ROS staining, aged (8-day old) smo-1 depleted animals exhibited higher H2O2 levels compared to control (Fig. 5E). Together, these findings suggest that SUMO represses mitochondrial activity during ageing via DAF-16. As readouts of mitochondrial function, we measured production of ATP and oxygen consumption rates in 4-day old animals. We did not detect significant change upon smo-1(RNAi) in wild type or daf-16(-) genetic background (Fig. S5A,B). daf-2(e1370) animals displayed lower oxygen consumption rates, and smo-1(RNAi) did not significantly alter this rate (Fig. S5B). On the contrary, knockdown of smo-1 resulted in higher ATP production in day 6 wild type animals (Fig. 5F), consistent with the TMRE and MitoTracker ROS staining results (Fig. 5A–D). Intriguingly, SMO-1 depletion reduced ATP levels in daf-2(e1370) and daf-16(mu86) animals (Fig. 5F), indicating that mitochondrial ROS and ATP production are uncoupled in these genetic backgrounds. To assay mitochondrial content, we used two methods: paraquat (4 mM) treatment followed by TMRE staining and mitochondrial DNA copy number measurement. Administration of paraquat leads to mitochondrial membrane potential dissipation; therefore, accumulation of TMRE reflects the number of mitochondria. Interestingly, downregulation of smo-1 increased the number of mitochondria during ageing in a DAF-16 dependent manner (Fig. S5C,D); but not mitochondrial DNA copy number (Fig. S5E,F). Thus, mitochondrial function and mass are upregulated upon smo-1 knockdown during ageing.

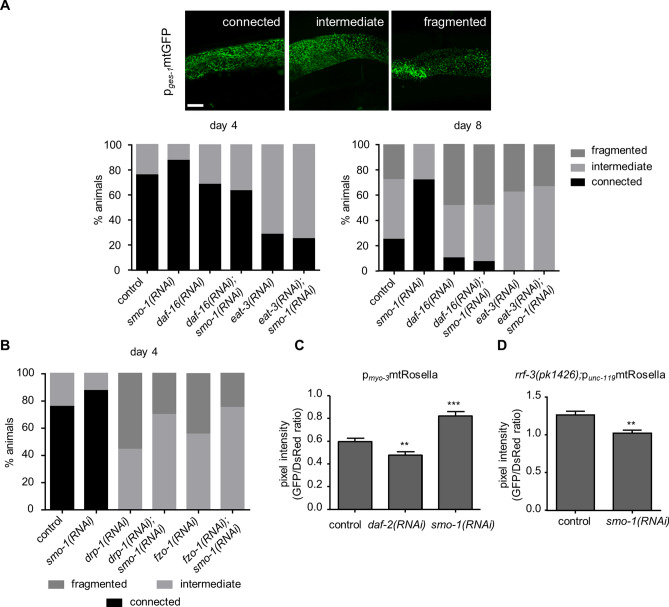

Alongside changes in mitochondrial activity, morphological alterations occur during ageing. The interconnected, tubular mitochondrial network in young animals becomes fragmented as they age9,10. We followed mitochondrial morphology during ageing using a mitochondrially localized pges-1mtGFP reporter fusion (Fig. 6A). The mitochondrial network displayed extended fragmentation by day 8 of adulthood in wild type, but not in SMO-1 depleted animals (Fig. 6A), indicating a requirement for SUMO for mitochondrial fission. DAF-16 has been implicated in the regulation of mitochondrial morphology10. We examined whether SMO-1 modulates mitochondrial morphology through DAF-16. Knockdown of daf-16 caused mitochondrial network fragmentation in SMO-1 deficient animals, during ageing (Fig. 6A). DAF-16 controls the expression of eat-3 (eating: abnormal pharyngeal pumping), a gene encoding the homologue of OPA1, a protein required for the fusion of inner mitochondrial membrane58,59. EAT-3 deficient animals display a fragile, fragmented intestinal mitochondrial network. Similarly to DAF-16, we find that downregulation of eat-3 triggered mitochondrial network fragmentation in SMO-1 deficient animals, during ageing (Fig. 6A). These findings indicate that SMO-1 modulates the morphology of mitochondria via DAF-16.

Figure 6.

SUMO is required for efficient mitochondrial fission and regulates mitophagy. (A) The intestinal mitochondrial network becomes fragmented in day 8 wild type animals, but remains interconnected in smo-1(RNAi) treated animals, and the mitochondrial network influencing effect of SMO-1 is DAF-16 and EAT-3 dependent, scale bar: 10 μm. Images were acquired using × 63 objective lens (n = 40). (B) In the absence of drp-1 or fzo-1 the mitochondrial network undergoes fragmentation, and the loss of smo-1 rescues this phenotype (n = 15). (C) daf-2(RNAi) increases, while smo-1(RNAi) inhibits mitophagy in muscle cells (n = 40, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, unpaired t-test). (D) Depletion of smo-1 induces neuronal mitophagy (n = 20, **p < 0.01, unpaired t-test). Error bars, S.E.M.

In addition to EAT-3/OPA-1, DRP-1 (dynamin related protein-1) and FZO-1 (Fzo mitochondrial fusion protein related), regulate mitochondrial network remodelling. Notably, DRP1 becomes SUMOylated in mitosis, cell death and ischemia60–63. In C. elegans, reduced expression of drp-1 or fzo-1 leads to mitochondrial network fragmentation10 (Fig. 6B). We find that smo-1 knockdown partially restores mitochondrial network connectivity upon drp-1 and fzo-1 downregulation (Fig. 6B). Combined, our observations suggest that SUMO is required for mitochondrial fission and exerts its effect on the mitochondrial fusion/fission machinery via DAF-16.

Previous studies have shown that mitochondrial fission is required for, and precedes mitophagy64. Since SUMO impinges on mitochondrial dynamics, we tested whether mitophagy is also affected upon downregulation of smo-1 expression. To monitor mitophagy, we used a mitochondria targeted, ratiometric Rosella biosensor, expressed in body wall muscle cells10. Under mitophagy-inducing, low insulin/IGF1 signalling conditions, in daf-2 mutants, the ratio of GFP/DsRed fluorescence is reduced, signifying mitophagy induction (Fig. 6C, S6A). By contrast, knockdown of smo-1 increased the GFP/DsRed ratio, indicating that SUMO depletion inhibits mitophagy (Fig. 6C, S6A). This observation is consistent with the block of mitochondrial fission upon smo-1 downregulation (Fig. 6B). Additionally, we also assayed mitophagy in the nervous system65, in the RNAi sensitive, rrf-3(pk1426) mutant background. Surprisingly, reduced smo-1 expression resulted in the induction of mitophagy in neurons (Fig. 6D, S6B). Thus, SUMO is required to perform mitochondrial fission and mitophagy in a tissue specific manner.

Discussion

The regulatory role of SUMO in the ageing process remains elusive, up to date. Earlier studies in mice uncovered a progressive increase of protein SUMOylation in brain and plasma, during ageing29. Notably, we find a similar increase in the amount of SUMO, during adulthood in C. elegans, both in whole worm lysates and in the mitochondrial fraction (Fig. 1A, S4A). Interestingly, reducing the expression of SUMO proteases did not have any lifespan altering effect under normal conditions (Fig. S1B,C). Presumably, the function of these proteases is redundant. Furthermore, under various stress conditions mild heat stress (25 °C), reduced translational rates (ife-2(-) mutant background) and low insulin signalling (daf-2(-) mutant background) the loss of ulp-1 resulted in an extended lifespan (Figs. S1D, 4B,D). Therefore, specific SUMO proteases have the potential to regulate longevity upon stress conditions. To define the exact role of each SUMO protease under distinct stress insults is an interesting topic for future investigations. SMO-1 is expressed in all animal tissues and mainly localizes to the nucleus66. Accordingly, the most studied functions of SUMO are nucleus-associated14,67,68; however, its role outside of the nucleus is emerging69, with a focus on the nervous system. Indeed, we find that tightly controlled expression level of smo-1 is a prerequisite for normal lifespan (Fig. 2). A recent study implicated SUMOylation of the germline RNA binding protein CAR-1 (cytokinesis, apoptosis, RNA-associated), in the regulation of lifespan by insulin signalling. Under low insulin signalling conditions (in daf-2 mutants), CAR-1 is less likely to be SUMO-modified, and can effectively inhibit glp-1 expression in the germline, allowing for lifespan extension28. Our findings indicate that DAF-16 and SKN-1 mediate the effects of SUMO on ageing, in the soma.

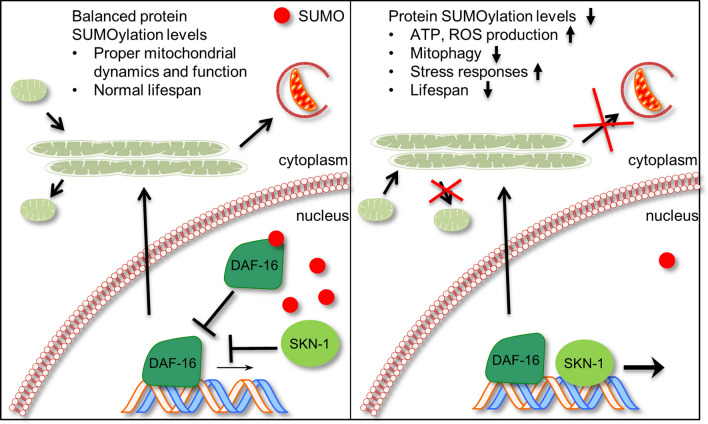

SUMOylation of transcription factors is mostly coupled with transcriptional repression70. Indeed, we found that DAF-16 is a target for SUMOylation, upon which, its transcriptional activity is quenched (Fig. 4). Under basal conditions this modification could serve to inhibit the unnecessary activation of stress response genes by nuclear localized DAF-16. Indeed, SUMO overexpression leads to the nuclear accumulation of DAF-16 (Fig. 4F); however, without the activation of DAF-16 target genes (Fig. 4G–J). Consequently, the long lifespan of SUMO overexpressing animals is only marginally shortened upon daf-16 knockdown (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, reduced skn-1 expression in the SUMO overexpressing background completely abolished lifespan extension in SUMO overexpressing animals (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that the interplay between DAF-16 and SKN-1 is an important determinant of the ageing mechanism. Notably, numerous pathways converge on organismal lifespan71; further studies could determine the DAF-16 independent, lifespan extending mechanisms upon SMO-1 overexpression in C. elegans. Removal of SUMO results in the upregulation of stress responsive genes, controlled by DAF-16 and SKN-1 (Figs. 4G–J, S2B,D). These findings are consistent with the reported functions of SUMOylation in the regulation of stress responses (e.g. DNA damage response, ER stress, heat shock), which are indispensable for cellular survival72. Furthermore, a recent study indicates that activation of SKN-1 negatively regulates DAF-16, which is in agreement with our data showing the increased expression of DAF-16 target genes upon skn-1(RNAi)73 (Fig. 4G,H). It would be interesting to analyse the role of SUMO in this interaction. Our results hint towards the possibility of the requirement of SUMO modification of DAF-16 for the successful SKN-1 repression. Thus, SUMO depletion compromises cellular homeostasis, and may, additionally, generate a state of cellular stress that contributes to early organismal death (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

SUMOylation and ageing. Under normal conditions protein SUMOylation is balanced by conjugation and cleavage events. This ensures the tight control of mitochondrial function and dynamics, allowing for a normal lifespan. Depletion of SUMO leads to activation of stress responses, impairment of mitochondrial function and mitophagy, which shortens lifespan. SUMO modulates the activity of the DAF-16 and SKN-1, stress response transcription factors to influence ageing.

SUMOylation has also been linked to mRNA translation regulation74, and chromatin organization55. Notably, hyposumoylation of chromatin has been associated with pluripotency reprogramming and enhanced lineage trans-differentiation75. We considered whether the changes in transgene expression upon SUMO depletion, or overexpression, in C. elegans are an indirect consequence of alterations in chromatin structure, and/or mRNA translation. We observed that downregulation of daf-2 is sufficient to restore expression of sod-3, a DAF-16 target gene, which is significantly reduced upon SUMO overexpression (Fig. 4H), indicating that the chromatin is still accessible under this condition. Furthermore, expression of gst-4, a SKN-1 target gene, is not affected by SUMO overexpression (Fig. S2B–D) and increases following paraquat treatment (Fig. 3E). By contrast, SUMO deficiency results in the upregulation of both sod-3, and gst-4 expression (Figs. 4H, S2B). Therefore, loss of SUMO engages stress response pathways, involving both DAF-16 and SKN-1 transcription factors (Fig. 7).

SUMOylation has been linked to mitochondrial biogenesis and network remodelling through PGC-1α and Drp1 in mammals63,76,77. Moreover, SUMO modification of ATFS-1 and DVE-1 play a regulatory role in the process of mitochondrial unfolded protein response (mtUPR)78. Here, we examined the involvement of SUMO in mitochondrial homeostasis. We observed an increase in mitochondrial content, but not in mitochondrial DNA copy number upon depletion of SUMO in C. elegans (Fig. S5C–F). Additionally, ATP and ROS production increases in aged animals, indicating elevated mitochondrial activity (Fig. 5C–F). Moreover, we found that SUMO promotes mitochondrial fragmentation during ageing (Fig. 6A,B) and it is also required for mitochondrial turnover via mitophagy in muscle cells (Fig. 6C). Intriguingly, SUMO blocks the process of mitophagy in the nervous system (Fig. 6D). Admittedly, increased mitophagy has been shown to have detrimental consequences on the homeostasis of the cell79,80. The tissue specific effects of SUMO on mitophagy merits further research. Notably, while in long-lived mutants, mitochondria display elongated morphology, coupled with reduced ROS production58, we find that short-lived, SUMO-depleted animals also feature elongated mitochondrial network, but elevated generation of ROS. This discrepancy indicates that mitochondrial turnover is differentially affected in long-lived, and short-lived, SUMO deficient mutants. In long-lived animals a healthy interconnected mitochondrial network is maintained by increased mitophagy, which moderates ROS production10. Instead, SMO-1 knockdown interferes with mitochondrial fission and fusion, which in turn impairs mitophagy, resulting in accumulation of mitochondrial damage, higher ROS levels, and shorter lifespan. Our observations suggest that SUMO decreases mitochondrial function and promotes mitochondrial fission during ageing in C. elegans (Fig. 7). These findings are consistent with recent studies suggesting that impairment of mitochondrial dynamics contributes to the decline of mitochondrial function during ageing and the onset of age-related diseases81.

Collectively, our findings indicate that SUMO influences the ageing process by modulating the transcriptional activity of the stress response transcription factors, DAF-16 and SKN-1 (Fig. 7). Admittedly, these are not the only transcription factors that could be affected by the depletion of SUMO. Further research is required to fully map the molecular changes in response to altered SUMO levels. Notably, recent studies have implicated SUMO in senescent decline. SUMOylation of p53 causes cellular senescence82, while deSUMOylation of Bmi1, a polycomb repressive complex member, is likewise, required for senescence83. Moreover, the SUMO E2 enzyme, Ubc9, regulates senescence by relocation of SUMOylated proteins to PML nuclear bodies84. Thus balanced protein SUMOylation is critical for stress resistance and survival. The ageing process disrupts SUMOylation balance while manipulations that fine-tune protein SUMOylation promote longevity.

Here, we demonstrate that the abundance of SUMO regulates lifespan. Reduced SUMO levels shorten lifespan, while increased smo-1 expression results in extended lifespan (Figs. 2, 7). SUMO influences ageing mainly through DAF-16 and SKN-1 (Figs. 3A,B, 4A,B), in a tissue specific manner, through the intestine and the nervous system (Fig. 2). We further show that DAF-16 is a target for SUMOylation, and that SUMO attachment represses the transcriptional activity of DAF-16 (Figs. 4, 7). We propose that under normal conditions, modification of DAF-16 by SUMO could prevent uncontrolled activation of nuclearly localized DAF-16 (Fig. 7). Accordingly, overabundance of SUMO leads to strong DAF-16 inhibition (Fig. 4H–J). Nonetheless, SUMO overexpressing animals exhibit long lifespan, which is dependent on SKN-1 (Fig. 3B) and in a lesser extent on DAF-16 (Fig. 4C). In addition, SUMO plays a critical role in the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis. Altering SUMO levels affects mitochondrial ATP and ROS production (Fig. 5), as well as, mitochondrial dynamics and clearance (Figs. 6, 7). Combined, our findings indicate that balanced protein SUMOylation is a prerequisite for healthy animal ageing.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Aggela Pasparaki for valuable support with confocal microscopy and Artemis Andreou for the smo-1(RNAi), ulp-1(RNAi) and psmo-1DsRed::SMO-1 constructs. We thank B. P. Braeckman for the HyPer biosensor strain (prpl-17HyPer). Some nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was funded by the European Commission 7th Framework Programme Marie Curie (FP7 ITN CodeAge 316354), an EMBO Short-Term Fellowship and Grants from the European Research Council (ERC GA695190, MANNA; ERC-GA737599, NeuronAgeScreen).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A.P. and N.T.; Methodology: A.P., F.P. and N.T.; Investigation: A.P.; Writing—Original Draft: A.P.; Writing—Review & Editing: N.T.; Supervision: F.P. and N.T.; Project Administration: N.T.; Funding Acquisition: N.T.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-72637-9.

References

- 1.Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruan L, Zhang X, Li R. Recent insights into the cellular and molecular determinants of aging. J. Cell Sci. 2018 doi: 10.1242/jcs.210831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366:461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin K, Dorman JB, Rodan A, Kenyon C. daf-16: An HNF-3/forkhead family member that can function to double the life-span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;278:1319–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenyon CJ. The genetics of ageing. Nature. 2010;464:504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy CT, Hu PJ. Insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling in C. elegans. WormBook Online Rev. C. elegans Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.164.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tissenbaum HA. DAF-16: FOXO in the context of C. elegans. Curr. Topics Dev. Biol. 2018;127:1–21. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tullet JM, et al. Direct inhibition of the longevity-promoting factor SKN-1 by insulin-like signaling in C. elegans. Cell. 2008;132:1025–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regmi SG, Rolland SG, Conradt B. Age-dependent changes in mitochondrial morphology and volume are not predictors of lifespan. Aging. 2014;6:118–130. doi: 10.18632/aging.100639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palikaras K, Lionaki E, Tavernarakis N. Coordination of mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis during ageing in C. elegans. Nature. 2015;521:525–528. doi: 10.1038/nature14300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hertweck M, Gobel C, Baumeister RC. elegans SGK-1 is the critical component in the Akt/PKB kinase complex to control stress response and life span. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:577–588. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi Y, et al. Asymmetric arginine dimethylation determines life span in C. elegans by regulating forkhead transcription factor DAF-16. Cell Metab. 2011;13:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Gao B, Lee SM, Bennett K, Fang D. RLE-1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, regulates C. elegans aging by catalyzing DAF-16 polyubiquitination. Dev. Cell. 2007;12:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flotho A, Melchior F. Sumoylation: A regulatory protein modification in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013;82:357–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061909-093311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkinson KA, Henley JM. Mechanisms, regulation and consequences of protein SUMOylation. Biochem. J. 2010;428:133–145. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pelisch F, et al. A SUMO-dependent protein network regulates chromosome congression during oocyte meiosis. Mol. Cell. 2017;65:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelisch F, et al. Dynamic SUMO modification regulates mitotic chromosome assembly and cell cycle progression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5485. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira HC, Towbin BD, Jegou T, Gasser SM. The shelterin protein POT-1 anchors Caenorhabditis elegans telomeres through SUN-1 at the nuclear periphery. J. Cell Biol. 2013;203:727–735. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201307181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaminsky R, et al. SUMO regulates the assembly and function of a cytoplasmic intermediate filament protein in C. elegans. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:724–735. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H, et al. SUMO modification is required for in vivo Hox gene regulation by the Caenorhabditis elegans Polycomb group protein SOP-2. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:507–511. doi: 10.1038/ng1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leight ER, Glossip D, Kornfeld K. Sumoylation of LIN-1 promotes transcriptional repression and inhibition of vulval cell fates. Development. 2005;132:1047–1056. doi: 10.1242/dev.01664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broday L, et al. The small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) is required for gonadal and uterine-vulval morphogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2380–2391. doi: 10.1101/gad.1227104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward JD, et al. Sumoylated NHR-25/NR5A regulates cell fate during C. elegans vulval development. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chowdhuri SR, Crum T, Woollard A, Aslam S, Okkema PG. The T-box factor TBX-2 and the SUMO conjugating enzyme UBC-9 are required for ABa-derived pharyngeal muscle in C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 2006;295:664–677. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huber P, et al. Function of the C. elegans T-box factor TBX-2 depends on SUMOylation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS. 2013;70:4157–4168. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1336-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher K, et al. Maintenance of muscle myosin levels in adult C. elegans requires both the double bromodomain protein BET-1 and sumoylation. Biol. Open. 2013;2:1354–1363. doi: 10.1242/bio.20136007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SH, Michael WM. Regulated proteolysis of DNA polymerase eta during the DNA-damage response in C. elegans. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:757–766. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moll L, et al. The Insulin/IGF signaling cascade modulates SUMOylation to regulate aging and proteostasis in C. elegans. eLife. 2018 doi: 10.7554/eLife.38635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ficulle E, Sufian MDS, Tinelli C, Corbo M, Feligioni M. Aging-related SUMOylation pattern in the cortex and blood plasma of wild type mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2018;668:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong D, Bazopoulou D, Pujol N, Tavernarakis N, Ewbank JJ. Genome-wide investigation reveals pathogen-specific and shared signatures in the response of Caenorhabditis elegans to infection. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R194. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofmann ER, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans HUS-1 is a DNA damage checkpoint protein required for genome stability and EGL-1-mediated apoptosis. Curr. Biol. CB. 2002;12:1908–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Artal-Sanz M, Tavernarakis N. Prohibitin couples diapause signalling to mitochondrial metabolism during ageing in C. elegans. Nature. 2009;461:793–797. doi: 10.1038/nature08466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelisch F, Hay RT. Tools to study SUMO conjugation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016;1475:233–256. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6358-4_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelisch F, Borja LB, Jaffray EG, Hay RT. Sumoylation regulates protein dynamics during meiotic chromosome segregation in C. elegans oocytes. J. Cell Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1242/jcs.232330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen L, et al. SUMO protease SENP1 induces isomerization of the scissile peptide bond. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:1069–1077. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palikaras K, Tavernarakis N. Intracellular assessment of ATP levels in Caenorhabditis elegans. Bio-Protocol. 2016 doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palikaras K, Tavernarakis N. Measuring oxygen consumption rate in Caenorhabditis elegans. Bio-Protocol. 2016 doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cristina D, Cary M, Lunceford A, Clarke C, Kenyon C. A regulated response to impaired respiration slows behavioral rates and increases lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Broday L. The SUMO system in Caenorhabditis elegans development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2017;61:159–164. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.160388LB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fraser AG, et al. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature. 2000;408:325–330. doi: 10.1038/35042517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones D, Crowe E, Stevens TA, Candido EP. Functional and phylogenetic analysis of the ubiquitylation system in Caenorhabditis elegans: ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, ubiquitin-activating enzymes, and ubiquitin-like proteins. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0002. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-3-1-research0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rera M, Azizi MJ, Walker DW. Organ-specific mediation of lifespan extension: More than a gut feeling? Ageing Res. .iews. 2013;12:436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tabara H, et al. The rde-1 gene, RNA interference, and transposon silencing in C. elegans. Cell. 1999;99:123–132. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81644-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Timmons L, Court DL, Fire A. Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene. 2001;263:103–112. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winston WM, Molodowitch C, Hunter CP. Systemic RNAi in C. elegans requires the putative transmembrane protein SID-1. Science. 2002;295:2456–2459. doi: 10.1126/science.1068836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calixto A, Chelur D, Topalidou I, Chen X, Chalfie M. Enhanced neuronal RNAi in C. elegans using SID-1. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:554–559. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hietakangas V, et al. Phosphorylation of serine 303 is a prerequisite for the stress-inducible SUMO modification of heat shock factor 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:2953–2968. doi: 10.1128/mcb.23.8.2953-2968.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Das R, et al. The homeodomain-interacting protein kinase HPK-1 preserves protein homeostasis and longevity through master regulatory control of the HSF-1 chaperone network and TORC1-restricted autophagy in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1007038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malloy MT, et al. Trafficking of the transcription factor Nrf2 to promyelocytic leukemia-nuclear bodies: Implications for degradation of NRF2 in the nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:14569–14583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.437392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hendriks IA, et al. Uncovering global SUMOylation signaling networks in a site-specific manner. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:927–936. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blackwell TK, Steinbaugh MJ, Hourihan JM, Ewald CY, Isik M. SKN-1/Nrf, stress responses, and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2015;88:290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun X, Chen WD, Wang YD. DAF-16/FOXO transcription factor in aging and longevity. Front. Pharmacol. 2017;8:548. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen AT, Guo C, Dumas KJ, Ashrafi K, Hu PJ. Effects of Caenorhabditis elegans sgk-1 mutations on lifespan, stress resistance, and DAF-16/FoxO regulation. Aging Cell. 2013;12:932–940. doi: 10.1111/acel.12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wotton D, Pemberton LF, Merrill-Schools J. SUMO and chromatin remodeling. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017;963:35–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-50044-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghose P, Park EC, Tabakin A, Salazar-Vasquez N, Rongo C. Anoxia-reoxygenation regulates mitochondrial dynamics through the hypoxia response pathway, SKN-1/Nrf, and stomatin-like protein STL-1/SLP-2. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1004063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Back P, et al. Exploring real-time in vivo redox biology of developing and aging Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2012;52:850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaudhari SN, Kipreos ET. Increased mitochondrial fusion allows the survival of older animals in diverse C. elegans longevity pathways. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:182. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00274-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kanazawa T, et al. The C. elegans Opa1 homologue EAT-3 is essential for resistance to free radicals. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zunino R, Braschi E, Xu L, McBride HM. Translocation of SenP5 from the nucleoli to the mitochondria modulates DRP1-dependent fission during mitosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:17783–17795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901902200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Figueroa-Romero C, et al. SUMOylation of the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 occurs at multiple nonconsensus sites within the B domain and is linked to its activity cycle. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Federation Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2009;23:3917–3927. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-136630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo C, et al. SENP3-mediated deSUMOylation of dynamin-related protein 1 promotes cell death following ischaemia. EMBO J. 2013;32:1514–1528. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prudent J, et al. MAPL SUMOylation of Drp1 stabilizes an ER/Mitochondrial platform required for cell death. Mol. Cell. 2015;59:941–955. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan DC. Fusion and fission: Interlinked processes critical for mitochondrial health. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012;46:265–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fang EF, et al. Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-beta and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:401–412. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Drabikowski K, et al. Comprehensive list of SUMO targets in Caenorhabditis elegans and its implication for evolutionary conservation of SUMO signaling. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1139. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19424-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bergink S, Jentsch S. Principles of ubiquitin and SUMO modifications in DNA repair. Nature. 2009;458:461–467. doi: 10.1038/nature07963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heun P. SUMOrganization of the nucleus. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2007;19:350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Henley JM, et al. SUMOylation of synaptic and synapse-associated proteins: An update. J. Neurochem. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jnc.15103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gill G. Something about SUMO inhibits transcription. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2005;15:536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Riera CE, Merkwirth C, De Magalhaes Filho CD, Dillin A. Signaling networks determining life span. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2016;85:35–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Enserink JM. Sumo and the cellular stress response. Cell Div. 2015;10:4. doi: 10.1186/s13008-015-0010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Deng J, Dai Y, Tang H, Pang S. SKN-1 is a negative regulator of DAF-16 and somatic stress resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 (Bethesda). 2020 doi: 10.1534/g3.120.401203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Enserink JM. Regulation of cellular processes by SUMO: Understudied topics. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017;963:89–97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-50044-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cossec JC, et al. SUMO safeguards somatic and pluripotent cell identities by enforcing distinct chromatin states. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:742–757.e748. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cai R, et al. SUMO-specific protease 1 regulates mitochondrial biogenesis through PGC-1alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:44464–44470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.422626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anderson CA, Blackstone C. SUMO wrestling with Drp1 at mitochondria. EMBO J. 2013;32:1496–1498. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gao K, Li Y, Hu S, Liu Y. SUMO peptidase ULP-4 regulates mitochondrial UPR-mediated innate immunity and lifespan extension. eLife. 2019 doi: 10.7554/eLife.41792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jin G, et al. Atad3a suppresses Pink1-dependent mitophagy to maintain homeostasis of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:29–40. doi: 10.1038/s41590-017-0002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yussman MG, et al. Mitochondrial death protein Nix is induced in cardiac hypertrophy and triggers apoptotic cardiomyopathy. Nat. Med. 2002;8:725–730. doi: 10.1038/nm719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sebastian D, Palacin M, Zorzano A. Mitochondrial dynamics: Coupling mitochondrial fitness with healthy aging. Trends Mol. Med. 2017;23:201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ivanschitz L, et al. PML IV/ARF interaction enhances p53 SUMO-1 conjugation, activation, and senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:14278–14283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507540112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xia N, et al. SENP1 is a crucial regulator for cell senescence through DeSUMOylation of Bmi1. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34099. doi: 10.1038/srep34099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McManus FP, et al. Quantitative SUMO proteomics reveals the modulation of several PML nuclear body associated proteins and an anti-senescence function of UBC9. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:7754. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25150-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.