Abstract

Many aggregation-prone proteins linked to neurodegenerative disease are post-translationally modified during their biogenesis. In vivo pathogenesis studies have suggested that the presence of post-translational modifications can shift the aggregate assembly pathway and profoundly alter the disease phenotype. In prion disease, the N-linked glycans and GPI-anchor on the prion protein (PrP) impair fibril assembly. However, the relevance of the two glycans to aggregate structure and disease progression remains unclear. Here we show that prion-infected knockin mice expressing an additional PrP glycan (tri-glycosylated PrP) develop new plaque-like deposits on neuronal cell membranes, along the subarachnoid space, and periventricularly, suggestive of high prion mobility and transit through the interstitial fluid. The plaque-like deposits were largely non-congophilic and composed of full length, uncleaved PrP, indicating retention of the glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. Prion aggregates sedimented in low density fractions following ultracentrifugation, consistent with oligomers, and bound low levels of heparan sulfate similar to other predominantly GPI-anchored prions. These results suggest that highly glycosylated PrP primarily converts as a GPI-anchored glycoform with low involvement of HS co-factors, limiting PrP assembly mainly to oligomers. Thus, these findings may explain the high frequency of diffuse, synaptic, and plaque-like deposits and rapid conversion commonly observed in human and animal prion disease.

Keywords: amyloid, neurodegeneration, glycosaminoglycans, ADAM10 cleavage, glycans, glycosylation, protein misfolding, prion strains

Introduction

Protein aggregation and neuronal loss are defining features of neurodegenerative disease [29, 32, 65], including prion disease [4]. In prion disease, the clinical progression is extraordinarily rapid, with a median survival of approximately six months for patients with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) [28, 74, 75]. A causal role for the aggregated prion protein, PrPSc, in disease development has been established [46, 47], supported most recently by studies showing disease induction from recombinant PrP fibrils [10, 16, 69]. Compared to amyloid-β fibrils that display limited structural polymorphs [53], prion aggregates are remarkably diverse, forming a wide range of polymorphs [56] and appearing histologically as diffuse, punctate, plaque-like, or congophilic plaques that vary biochemically [8, 42]. Similar to other proteins that aggregate in neurodegenerative disorders, PrP is post-translationally modified [5, 19, 51, 60–62], yet how PrP post-translational modifications contribute to the aggregate conformation, co-factor interactions, and disease progression is unclear.

PrPC is a ubiquitously expressed monomeric protein composed of 208 amino acids [13, 41] maintained in the outer plasma membrane by a glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor [5, 51]. The N-terminus is largely unstructured, whereas the C-terminal globular domain is composed of three α-helices with up to two N-linked glycans and a single disulfide bond that enhances protein stability [49]. During prion disease, PrPC undergoes a major structural transformation from largely α-helical to β-sheet [6, 12]. PrPSc multimers template the misfolding of PrPC, exponentially increasing PrPSc levels [52, 63].

Prion diseases are considered amyloid disorders, yet amyloid plaques composed of ultrastructurally visible fibrils are uncommon in sporadic human and animal prion disease [26, 74]. Notably, the prion protein is an atypical amyloidogenic protein, as it is relatively large, highly structured, glycosylated, and GPI-anchored. GPI-anchorless PrP aggregates assemble as fibrils in humans and in experimental models [14, 25, 31], suggesting that the GPI-anchor hinders fibril formation.

N-linked glycans may also limit PrP fibril formation. Glycans stabilize proteins [15, 20, 45], facilitate proper folding in the endoplasmic reticulum [66, 70] and may impair fibril formation by shielding and stabilizing intramolecular disulfide bonds, as shown for a human PrP glycopeptide (175–195) [7]. Glycans may also decrease PrP interactions with anionic co-factors and potential scaffolds for fibril formation, such as sulfated glycosaminoglycans [54]. However, glycans have been also shown to facilitate oligomer formation, depending on the chemical composition and location of the sugar present [38].

Thus on the one hand, glycans may stabilize the tertiary structure of PrPC, raising the energy barrier for conversion and prolonging survival time. On the other hand, glycans may not alter the barrier for conversion but only hinder fibril elongation, restricting prions to small oligomers that transit readily through the brain thereby accelerating disease progression. To better understand the impact of PrP glycans on prion disease, we previously inoculated Prnp187N knockin mice, expressing PrPC with up to three glycans, with a fibrillar plaque-forming strain known as mCWD [55]. Interestingly, the neuropathological phenotype switched from plaques to fine, granular PrPSc deposits, and the survival time dropped by 60% as compared to infected wild type (WT) mice [54]. Conversely, mice expressing unglycosylated PrP (Prnp180Q,196Q) inoculated with two non-plaque-forming prion strains instead developed large plaques (approximately 100 um) containing ADAM10-cleaved PrPSc, which suggests that glycans inhibit fibril formation. To help resolve the question of how PrP glycans on the carboxy terminus impact prion disease, here we inoculated Prnp187N mice with four prion strains and determined survival times and prion distribution in the brain and spinal cord. We used an antibody targeting ADAM10-cleaved PrP [35] to measure the cleaved PrPSc levels, and mass spectrometry to measure the level and composition of prion-bound heparan sulfate (HS), which binds to plaque-forming prions [37, 54, 57, 59]. We found that all four prion strains were readily converted and showed a similar or slightly longer survival time than WT mice, yet with less spongiform change in the brain. Additionally, for two of four strains, mice developed plaque-like aggregates, which associate with neuronal membranes, retain the GPI-anchor, bind low levels of HS, and sediment in low density iodixanol fractions after ultracentrifugation, suggestive of smaller or less compact multimers. Finally, we compare our results to highly glycosylated human and animal prions, and propose a model for how glycans may underlie the extraordinary diversity in aggregate morphology and survival time in prion disease.

Materials and Methods

PrPC expression in uninfected wild-type and Prnp187N brain

To measure total PrPC levels in WT (C57BL/6) and Prnp187N brain samples, 40 μg of 10% brain homogenate from uninfected mice was lysed in 2% N-lauryl sarcosine. Samples were then incubated for 15 minutes at 37 °C shaking at 1000 rpm. NuPage loading dye (Invitrogen) was added and samples were heated at 95 °C for 6 minutes prior to electrophoresis and transfer to nitrocellulose. Membranes were incubated in either anti-PrP antibody POM1 (epitope in the globular domain, amino acids 121–231 of the mouse PrP) [43], A228 antibody against ADAM 10-cleaved PrP (sPrPG228 epitope at residue 228G [35]), or anti β-tubulin as a loading control (Cell Signaling Technology) and developed using chemiluminescent substrate. The chemiluminescent signals were captured and quantified using the Fuji LAS 4000 imager and Multigauge V3.0 software.

Structure Modeling

Images were created using PyMol version 2.3.3. PrP crystal structure was obtained from PDB ID code 1AG2. N-linked glycans were modeled using the Glycam glycoprotein builder [27]. Tetra-antennary, sialic acid-containing N-linked glycans were chosen for the purposes of modeling due to evidence that the pool of PrP N-linked glycans contain bi-, tri-, and tetra-antennary glycans that contain primarily 2,6-linked sialic acid [30, 50].

Prion transmission experiments in mice

Groups of 4–11 male and female Prnp187N and WT (C57BL/6) mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine and inoculated into the left parietal cortex with 30 μl of 1% prion-infected brain homogenate prepared from terminally ill mice. The prion strains used for inoculation were mouse-adapted RML, 22L, ME7, and mNS. The RML, 22L, and ME7 are cloned prion strains that have been maintained in C57BL/6 mice [3, 9, 17, 18], while mNS inoculum was derived from repeated passage of a single scrapie‐infected sheep brain [3, 55] propagated in tga20 and WT (C57BL/6) mice. For the serial passages of prions in Prnp187N mice, homogenates from individual mouse brains were used. As negative controls, groups of age-matched WT (C57BL/6) and Prnp187N mice (n= 4–5 mice/ group) were inoculated intracerebrally with mock brain homogenate from uninfected WT mice and housed under the same conditions as the prion-infected-mice.

Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions on a 12:12 light/dark cycle, and monitored three times weekly for the development of prion disease, including weight loss, ataxia, kyphosis, stiff tail, hind leg clasp, and hind leg paresis. Mice were euthanized at the onset of terminal clinical signs, and the incubation period was calculated from the day of inoculation to the day of terminal clinical disease. During the necropsy, one hemi-brain was formalin-fixed, then immersed in 96–98% formic acid for 1 hour, washed in water, and post-fixed in formalin for 2–4 days. Hemi-brains were then cut into 2 mm transverse sections and paraffin-embedded for histological analysis. The remaining brain sections were frozen for biochemical analyses.

Histopathology and immunohistochemical stains

Four micron sections were cut onto positively charged silanized glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), or immunostained using antibodies for total PrP (SAF84)(Cayman Chemical), astrocytes (glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP), and heparan sulfate (10E4)(AMS Bioscience). PrP (SAF84; 1:400) and GFAP immunolabelling (DAKO; 1:6,000) was performed on an automated tissue immunostainer (Ventana Discovery Ultra, Ventana Medical Systems, Inc) with antigen retrieval performed by heating sections in a Tris-based EDTA buffer at 95 °C for 92 minutes or using a protease treatment (P2, Ventana) for 16 minutes, respectively. For HS immunolabelling, epitope retrieval was performed by placing sections in citrate buffer (pH 6), heating in a pressure cooker for 20 minutes, cooling for 5 minutes, and washing in distilled water. Sections were blocked and incubated with anti-heparan sulfate antibody for 45 minutes followed by anti-mouse biotin (Jackson Immunolabs; 1:250) for 30 minutes and then streptavidin-HRP (Jackson Immunoresearch) for 45 minutes. Slides were then incubated with DAB reagent (Thermo Scientific) for 15 minutes. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Control slides for the HS stain were treated with heparin lyases I,II, III at 37 °C for 60 minutes prior to immunoIabelling. To quantify plaque size in ME7 and mNS-infected mice, brain sections containing plaques were imaged at high magnification (400X) and the diameter at the largest point of the plaque was measured using ImageJ software (N ≥ 35 plaques or plaque-like deposits from three mice per group).

For the Congo red staining, slides were deparaffinized, fixed in 70% ethanol for 10 minutes, immersed in an alkaline solution and then stained with Congo red solution overnight.

For the CD9 and total PrP co-immunostain of brains sections, epitope retrieval was first performed by immersing the sections in 96% formic acid for 5 minutes, digesting sections with 5 μg/ml PK for 10 minutes, and then heating slides in citrate buffer within a pressure cooker for 20 minutes, washing slides between each step. CD9 and PrP were labelled using anti-CD9 and anti-PrP antibodies (CD9: Novus; PrP: SAF84 from Cayman Chemical), and then sequentially, anti-rabbit HRP followed by tyramide-Alexa488 (CD9) followed by anti-mouse CY3, to label CD9 and PrP, respectively.

Lesion profile

Brain lesions from prion-infected WT (C57BL/6) and Prnp187N mice were scored for the level of spongiosis, gliosis, and PrP immunological reactivity on a scale of 0–3 (0= not detectable, 1= mild, 2= moderate, 3= severe) in 7 regions including grey and white matter: (1) dorsal medulla, (2) cerebellum, (3) hypothalamus, (4) medial thalamus, (5) hippocampus, (6) medial cerebral cortex dorsal to hippocampus, and (7) cerebral peduncle. A sum of the three scores resulted in the value obtained for the lesion profile for the individual animal and was depicted in the ‘radar plots’. Two investigators blinded to animal identification performed the histological analyses. Groups of 4–6 mice were analyzed for each strain.

PK-resistant PrPSc analyses

Brain homogenates were lysed in 2% N-lauryl sarcosine in PBS and incubated in PBS or digested with 50 μg/ml PK for 30 minutes at 37 °C prior to western blotting. Membranes were incubated with monoclonal antibody POM1, POM19 (epitope in the globular domain), POM2 (epitope in the flexible N-terminal tail), or POM3 (epitope in the flexible N-terminal tail) where indicated [43].

For measuring shed PrPSc by western blot, PrPSc from ME7- and mNS-infected Prnp187N mice and mCWD-infected mice was concentrated from 10% brain homogenate by performing sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation prior to western blotting [68]. In brief, 10% brain homogenate in an equal volume of 4% sarkosyl in PBS was digested with benzonase™ (Sigma) followed by treatment with 100 μg/ml PK at 37 °C for 30 minutes. After addition of 4% sodium phosphotungstic acid in 170 mM MgCl2 and protease inhibitors (Complete TM, Roche), extracts were incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes and centrifuged at 18,000 g for 30 minutes at 25 °C. Pellets were resuspended in 2% N-lauryl sarcosine prior to electrophoresis and immunoblotting. Membranes were incubated with monoclonal antibody POM19 [43] or polyclonal antibody sPrPG228 [35] followed by incubation with an HRP-conjugated IgG secondary antibody. The blots were developed using a chemiluminescent substrate (Supersignal West Dura ECL, ThermoFisher Scientific) and visualized on a Fuji LAS 4000 imager. Quantification of PrPSc glycoforms and total PrPSc was performed using Multigauge V3 software (Fujifilm).

Velocity Sedimentation

Brain homogenate [10% in PBS (w/v)] from WT (C57BL/6) or Prnp187N mice was lysed in velocity sedimentation lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% N-lauryl sarcosine, final) for 30 minutes, carefully placed over a 4 – 24% step gradient (4%, 8%, 12%, 16%, 20%, and 24%), and centrifuged at 150,000 g for 1 hour. Fourteen fractions were collected from each tube, with the final fraction including the resuspended pellet. Aliquots of each fraction were digested with 50 μg/ml of PK for 30 min at 37 °C prior to immunoblotting and probing with anti-PrP antibody, POM19 [43].

Purification of PrPSc for mass spectrometry studies

PrPSc was purified from mouse brain following previously described procedures [48], with minor modifications. 10% brain homogenate was mixed with an equal volume of TEN(D) buffer [5% sarkosyl in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 665 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol, pH 8.0), containing complete TM protease inhibitors (Roche)] and incubated on ice for 1 hour prior to centrifugation at 18,000 g for 30 minutes at 4 °C. All but 100 μl of supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of residual supernatant and diluted to 1 ml with 10% sarkosyl TEN(D). Each supernatant and pellet was incubated for 30 minutes on ice and then centrifuged at 22,000 g for 30 minutes at 4 °C. Supernatants were recovered while pellets were held on ice. Supernatants were added to ultracentrifuge tubes with 10% N-lauryl sarcosine TEN(D) buffer containing protease inhibitors and centrifuged at 150,000 g for 2.5 hours at 4 °C. Supernatants were discarded while pellets were rinsed with 100 μl of 10% NaCl in TEN(D) buffer with 1% sulfobetaine (SB3–14) and protease inhibitors and then combined with pellets and centrifuged at 225,000 g for 2 hours at 20 °C. The supernatant was discarded and pellet was washed and then resuspended in ice cold TMS buffer containing protease inhibitors (10 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.0). Samples were incubated on ice overnight at 4 °C. Samples were then incubated with 25 units/ml benzonase™ (Sigma-Aldrich) and 50 mM MgCl2 for 30 minutes at 37 °C followed by a digestion with 10 μg/ml PK for 1 hr at 37 °C. PK digestion was stopped by incubating samples with 2 mM PMSF on ice for 15 minutes. Samples were incubated with 20 mM EDTA for 15 minutes at 37 °C. An equal volume of 20% NaCl was added to all tubes followed by an equal volume of 2% SB3–14 buffer. For the sucrose gradient, a layer of 0.5 M sucrose in buffer [100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, and 0.5% SB3–14 (pH 7.4)] was added to ultracentrifuge tubes. Samples were then carefully overlaid on a sucrose layer and the tubes topped with TMS buffer. Samples were centrifuged at 200,000 g for 2 hours at 20 °C. The pellet was rinsed with 0.5% SB3–14 in PBS, resuspended in 50 μl of 0.5% SB3–14 in deionized water, and stored at −80 °C. Gel electrophoresis and silver staining were performed to assess the purity of brain extracts. To quantify PrP levels, samples were compared against a dilution series of recombinant PrP by immunoblotting and probing with the anti-PrP antibody POM19 [43].

Heparan sulfate purification and analysis by mass spectrometry

Heparan sulfate (HS) was extracted from the purified PrPSc preparation or from whole brain homogenate (10%, w/v) by anion exchange chromatography as described previously [1]. Purified PrPSc and brain homogenates were denatured in 0.5 M NaOH (final concentration) on ice at 4 °C for 16 hours, neutralized with 0.5 M acetic acid (final concentration), and digested with pronase for 25 hours at 37 °C. HS was then purified by diethyl-aminoethyl (DEAE) sepharose chromatography (Healthcare Life Sciences), and digested with 1 milli-unit each of heparin lyases I, II, and III to depolymerize the HS chains. The disaccharides were then tagged by reductive amination with [12C6]aniline [34] and mixed with [13C6]aniline-tagged disaccharide standards. Samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) using an LTQ Orbitrap Discovery electrospray ionization mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Internal disaccharides and nonreducing end monosaccharides were identified based on their unique mass and quantified relative to the HS weight [33, 34].

Statistics

A Student’s t test (two-tailed, unpaired) was used to determine the statistical significance between the Prnp187N versus WT mouse brain samples for the PrPC level of expression, levels of ADAM10-cleaved PrPC and PrPSc, as well as levels of HS bound to PrPSc in ME7-infected WT and Prnp187N brains. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post test was performed to assess survival differences between mouse groups. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post test was performed to assess differences in the lesion profiles, the glycoprofiles of PrPSc in WT and Prnp187N mice infected with the four different PrPSc strains, and the composition of HS bound to PrPSc in ME7-infected Prnp187N and WT mouse brain. GraphPad Prism 5® software was used for statistical analyses. No measurement was excluded for statistical analysis. For all analyses, P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Data displayed in graphs represent mean ± SEM.

Study approval

All animal studies were performed following procedures to minimize suffering and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at UC San Diego. Protocols were performed in strict accordance with good animal practices, as described in the Guide for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health.

Results

PrnpT187N mice are highly susceptible to prion infection

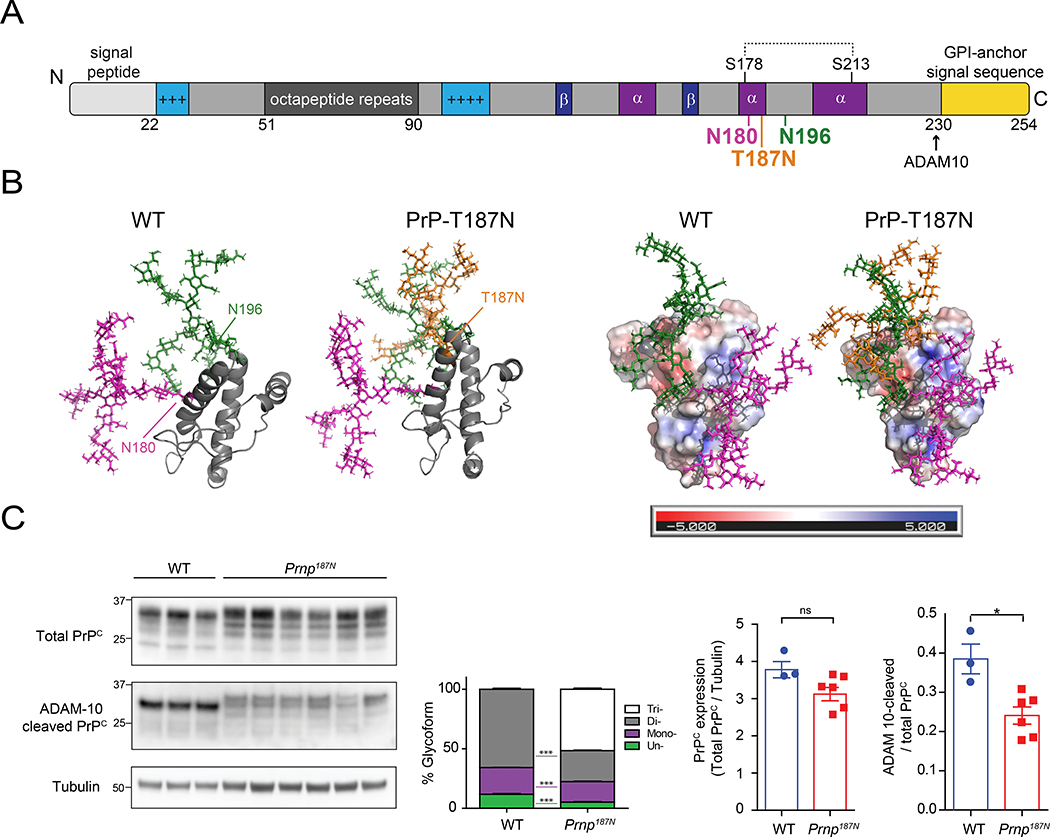

To investigate how glycans impact prion conversion, we compared prion infection in WT and Prnp187N knockin mice, which express PrP with 0–2 or 0–3 N-linked glycans in the C-terminal globular domain of PrP, respectively. The Prnp187N mice have a third glycan at position 187 (mouse PrP numbering) from a single amino acid substitution (T187N) that creates a novel N-linked glycan sequon (NXS or NXT) (TVT to NVT) [54] (Fig. 1A). The glycan is located at the C-terminal end of helix 2, nearly equidistant between the two physiological glycans at positions 180 and 196 [54] (Fig. 1A, B).

Figure 1. The T187N mutation introduces a third N-linked glycan to the globular C-terminal domain of PrPC.

A. The PrPC primary structure shows the positively charged segments (light blue), Cu2+-binding octapeptide repeats (dark grey), beta sheets (dark blue), alpha helices (purple), disulfide bonds (dotted line), and GPI-anchor signal sequence (yellow). The glycans are linked to PrP residues 180N and 196N, and to the mutated 187N residue. B. Three-dimensional structure of the mature PrPC protein shown in ribbon form (left) or as a charged surface (right) (PDB ID code 1AG2). N-linked glycans attached to N180, N196, and N187 are depicted in magenta, green, and orange, respectively (note: tetra-antennary, terminally-sialylated glycans are shown [30, 50]). C. Western blots (left) show total and ADAM10 cleaved PrPC protein levels in whole brain lysates from adult WT or Prnp187N mice. Graphs indicate relative percentages of each glycoform from total PrP: un- (green), mono- (purple), di- (grey), and tri-glycosylated (white) (mean ± SEM). Also quantified is ADAM10-cleaved PrP. N = 3 – 6 mice per genotype.

We previously found that Prnp187N and WT mice express equivalent PrPC levels in the brain [54]. The additional glycan altered PrP187N electrophoretic migration by approximately 2 kDa (Fig. 1C). PrP187N was more highly glycosylated with significantly lower levels of the unglycosylated PrP glycoform (Fig. 1C). To measure PrPC shed from the cell surface by ADAM10, we used a newly developed antibody (sPrPG228) that specifically recognizes the new C-terminal epitope generated upon proteolytic cleavage [35], and found a 1.6-fold decrease in cleaved PrPC, indicating reduced shedding of triglycosylated PrPC from the cell surface (Fig. 1C). Hence, in contrast to WT PrPC, where the fully (di-) glycosylated form is the predominant substrate for ADAM10 (Fig. 1C) [35], an additional third glycan at position 187 impairs this cleavage, possibly due to steric hindrance.

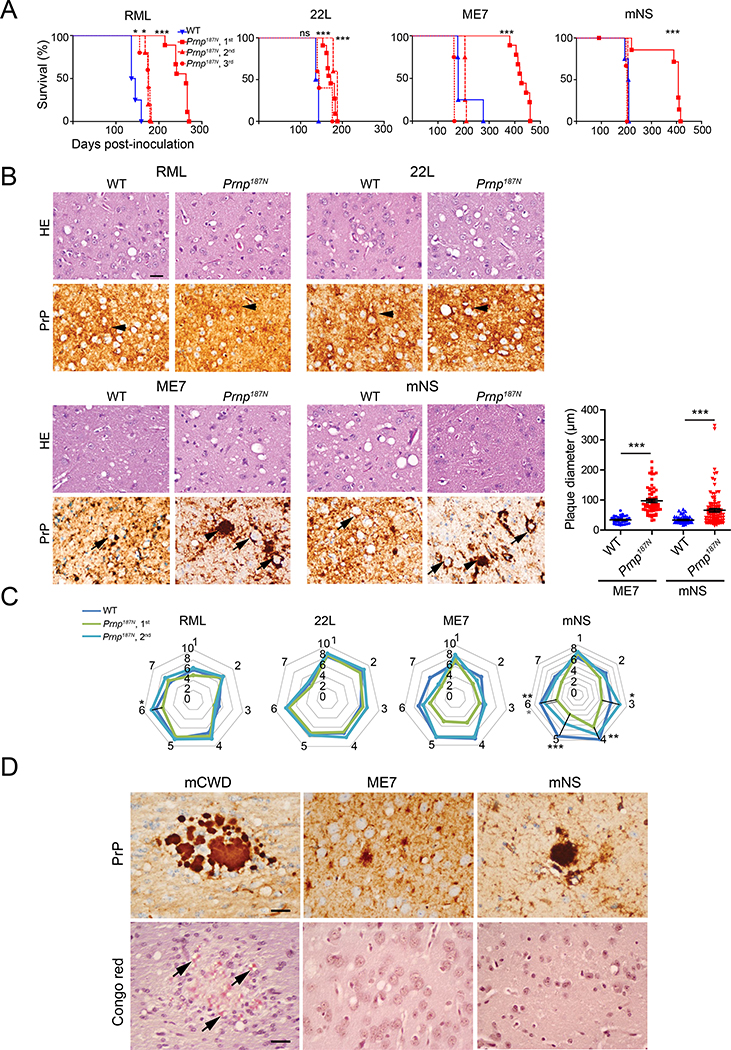

To determine how a third glycan would impact prion conversion, neurodegeneration, and survival time, we inoculated mice intracerebrally with four distinct subfibrillar, mouse-adapted prion strains. On first passage, Prnp187N mice showed a 100% attack rate, but a markedly prolonged survival period compared to the WT mice (Fig. 2A, Table 1). However, by the second or third passage, three of four strains no longer showed a difference in survival time, indicating that the third glycan made little difference in conversion once the strain was adapted. For the RML-infected mice, the Prnp187N mice survived approximately 20% longer than WT mice (WT: 144 ± 5 days; Prnp187N: 173 ± 5 days). The variance in the survival times among the Prnp187N mice infected with four prion strains was also similar to the WT mice (Prnp187N: 155 – 207 days; WT: 140 – 205 days).

Figure 2. Prnp187N mice initially show a prolonged survival time and plaque-like prion deposits in the brain for select strains.

A. Survival curves reveal a delayed time to the onset of terminal disease on the first passage for all strains, which decreased on subsequent passages. B. HE and PrP immunostains revealed similar spongiform degeneration and diffuse PrPSc deposits in the RML and 22L-infected WT and Prnp187N mice (arrowheads). Plaque-like deposits (arrowheads) were significantly larger in the ME7- and mNS-infected Prnp187N mice. Graph indicates plaque diameter (N=3 mice per group, n ≥ 35 plaques). Note the peri-neuronal prion deposits in the ME7 and mNS-infected WT and Prnp187N brain (arrows). C. Lesion profiles indicate the severity of spongiform change, astrogliosis, and PrPSc deposition in 7 brain areas and are nearly superimposable for RML and 22L-infected WT and Prnp187N mice. ME7- and mNS-infected mice showed less severe histopathologic lesions on first passage as compared to WT mice, however lesion severity increased by second passage (1-dorsal medulla, 2-cerebellum, 3-hypothalamus, 4-medial thalamus, 5-hippocampus, 6-cerebral cortex, 7-cerebral peduncles). For panel C: n=4–6 mice/group. D. Prion-like ME7 and mNS plaques in the Prnp187N brains are largely non-congophilic, unlike the mouse-adapted CWD prion strain (mCWD) used as a positive control. Brain regions shown in B: RML and 22L, cerebral cortex; ME7 and mNS, thalamus, and (D) Congo red stain: mCWD, corpus callosum; ME7 and mNS, cerebral cortex. Scale bar = 50 μm (panel B). *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001, Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (panel A), unpaired t-test (panel B), 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post (panel C).

Table 1.

Incubation times for WT or Prnp187N mice inoculated with RML, 22L, ME7, or mNS prion strains. Attack rate was 100% for all inoculated mice.

| Host | Prion | Passage | Number of mice | Incubation time Mean ± SEM (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | RML | 4/4 | 144 ± 5 | |

| Prnp187N | RML | 1 | 9/9 | 252 ± 6 |

| Prnp187N | Prnp187N-RML | 2 | 5/5 | 175 ± 2 |

| Prnp187N | Prnp187N-RML | 3 | 5/5 | 173 ± 5 |

| WT | 22L | 4/4 | 140 ± 2 | |

| Prnp187N | 22L | 1 | 11/11 | 173 ± 3 |

| Prnp187N | Prnp187N-22L | 2 | 5/5 | 184 ± 2 |

| Prnp187N | Prnp187N-22L | 3 | 5/5 | 155 ± 9 |

| WT | ME7 | 4/4 | 203 ± 25 | |

| Prnp187N | ME7 | 1 | 9/9 | 429 ± 9 |

| Prnp187N | Prnp187N-ME7 | 2 | 4/4 | 207 ± 1 |

| Prnp187N | Prnp187N-ME7 | 3 | 4/4 | 164 ± 1 |

| WT | mNS | 4/4 | 205 ± 4 | |

| Prnp187N | mNS | 1 | 7/7 | 428 ± 22 |

| Prnp187N | Prnp187N-mNS | 2 | 5/5 | 205 ± 0 |

| Prnp187N | Prnp187N-mNS | 3 | 3/3 | 200 ± 1 |

To assess how the third glycan affects the severity and regional distribution of neurodegeneration and gliosis, we scored eight brain regions for spongiform degeneration, gliosis, and PrPSc deposition. Interestingly, RML-infected Prnp187N and WT brains displayed similar diffuse aggregate morphology (Fig. 2B) and the lesion profiles were nearly overlapping (Fig. 2C), despite a 30-day difference in the incubation period. The 22L-infected Prnp187N brains also showed lesions that were nearly identical to WT (Fig. 2C). However, in Prnp187N mice infected with ME7 or mNS prions, there was a consistent decrease in the lesion severity, although the brain regions targeted were unchanged (Fig. 2B, 2C). The primary difference was a profound increase in the size of the plaque-like structures in the Prnp187N brains infected with ME7 prions [average plaque diameter 34 ± 2 μm (WT) versus 97 ± 6 μm (Prnp187N)] and mNS prions [average plaque diameter 34 ± 2 μm (WT) versus 66 ± 6 μm (Prnp187N)] (Fig. 2B).

ME7 and mNS prions typically form plaque-like structures and accumulate perineuronally inWT mice [39]. We found that the cell tropism was similar in Prnp187N mice, as prions from either strain also accumulated perineuronally. Yet exclusively in the Prnp187N mice, neurons showed a prominent piling of prion aggregates extending outward from the surface, sometimes obscuring the neuron, suggesting a difference in the aggregate arrangement of highly glycosylated PrP (Fig. 2B). PrPSc also frequently accumulated along the subarachnoid space and ventricular surfaces in the Prnp187N mice, potentially indicating PrPSc transit through the interstitial fluid. Neuronal and meningeal aggregates were non-congophilic (Figs. 2D and S1) and periventricular aggregates were only rarely and focally congophilic (Fig. S1). To determine whether the PrPSc was associated with extracellular vesicles (EVs), we co-immunolabelled brain sections for PrP and the tetraspanin and EV marker, CD9 (Fig. S2). Although PrP did not co-localize with CD9 in the WT mice, interestingly, there were focal PrP deposits that co-labelled with CD9 in the Prnp187N mice infected with ME7 or mNS prions, particularly periventricularly, suggesting that a subset of 187N-PrPSc may be attached to EVs.

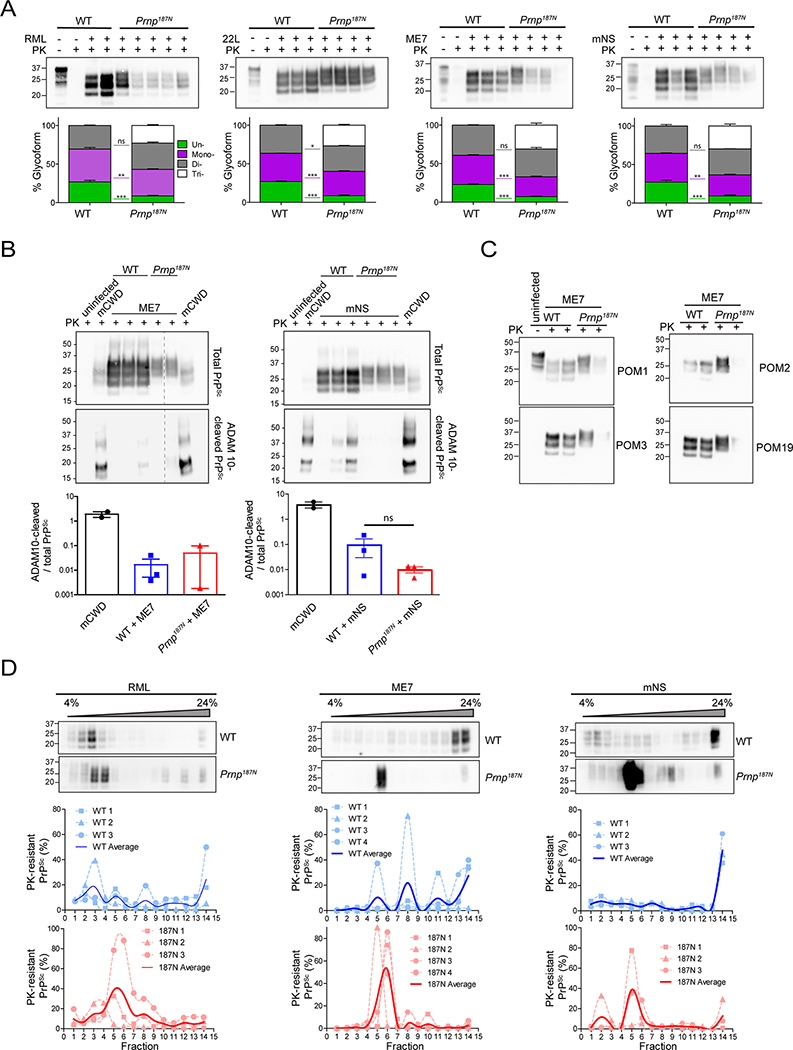

Triglycosylated PrPSc is largely GPI-anchored and sediments slowly

We assessed the PrPSc glycoform ratios by western blot and found that (1) all four strains converted tri-glycosylated PrP into PK-resistant PrPSc (Fig. 3A), and (2) unglycosylated PrPSc levels were significantly lower for Prnp187N strains than for WT strains (Fig. 3A), potentially due to the lower levels of unglycosylated PrPC (Fig. 1C).

Figure 3. Biochemical properties of 187N-PrPSc.

A. Electrophoretic mobility and glycoform profile of PrPSc from RML-, 22L-, ME7-, or mNS-prion-infected brain lysates (upper) show low levels of unglycosylated PrPSc in the Prnp187N mice brain. Lysates were treated with proteinase K (PK) where indicated to degrade PrPC. Quantification of glycoforms (lower) show percentage of PrPSc that contains zero (green), one (purple), two (grey), or three glycans (white). B. Representative western blots of ME7- or mNS-infected brain lysates from WT or Prnp187N mice show total (upper) or ADAM10-cleaved PrPSc shed from the cell surface (lower). Brain from mCWD-infected mice contain abundant ADAM10-cleaved PrPSc (positive control) [54]. Graphs show quantification (mean ± SE). C. Western blots show ME7-infected brain using antibodies against the octapeptide region of the PrP N-terminus (amino acids 53–88) (POM2), amino acids 95–100 (POM3), and a discontinuous epitope that includes the middle and distal C-terminus, which includes amino acid220 (POM19) [43]. D. Western blots from a sedimentation velocity of RML, mNS, or ME7 prion-infected WT or Prnp187N mice overlayed on a 4–24% Opti-prep™ step gradient, with the pellet fraction in the far right lane. Quantifications are shown below. N = 3 – 4 biological replicates per genotype for each strain, except for ME7-infected Prnp187N shown in panel B (N = 2).

We previously found that mCWD plaques were enriched in ADAM10-cleaved PrPSc. To determine the levels of ADAM10-cleaved PrPSc in ME7- and mNS-infected Prnp187N and WT brain, we immunoblotted PK-cleaved brain proteins using the sPrPG228 antibody. We found that the cleaved PrPSc levels were consistently lower by more than a log-fold as compared to mCWD, suggesting that PrPSc in ME7- and mNS-infected brains remained largely GPI-anchored (Fig. 3B).

To next test whether the prions were internally cleaved as observed in genetic prion disease associated with the F198S-PRNP mutation, we probed PK-resistant PrPSc with a series of antibodies against N- and C-terminal epitopes in PrP. However, no short internal fragments were evident for the ME7 strain, as the highly PK-resistant unglycosylated core fragment was consistently full length and the same molecular weight as WT PrPSc (Fig. 3C), indicating that PrP was likely to be largely GPI-anchored and not a PrP fragment.

The glycans attached to PrP may impair fibril formation, restricting PrPSc to small aggregates. To probe the sedimentation properties of highly glycosylated PrPSc, we performed velocity sedimentation on mNS- and ME7-infected brain samples, both of which displayed alterations in plaque morphology and lesion profiles in the Prnp187N mice. We also performed velocity sedimentation on RML-infected brain, in order to include a strain that was not altered by the additional glycan. Brain homogenate was solubilized in a sarcosyl-based buffer, overlaid onto a 4–24% Optiprep™ step gradient, and centrifuged at 150,000 g. Interestingly, the tri-glycosylated mNS and ME7 prions sedimented in lighter fractions than the WT mNS and ME7 prions (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the tri-glycosylated mNS and ME7 prion aggregates were smaller or less compact than the less glycosylated WT prions. Additionally, the PrP187N aggregates were notably more homogenous and nearly monodispersed, as compared to the polydispersed particles in WT mice. By comparison, the RML prion particles from both mouse lines sedimented similarly (Fig 3D).

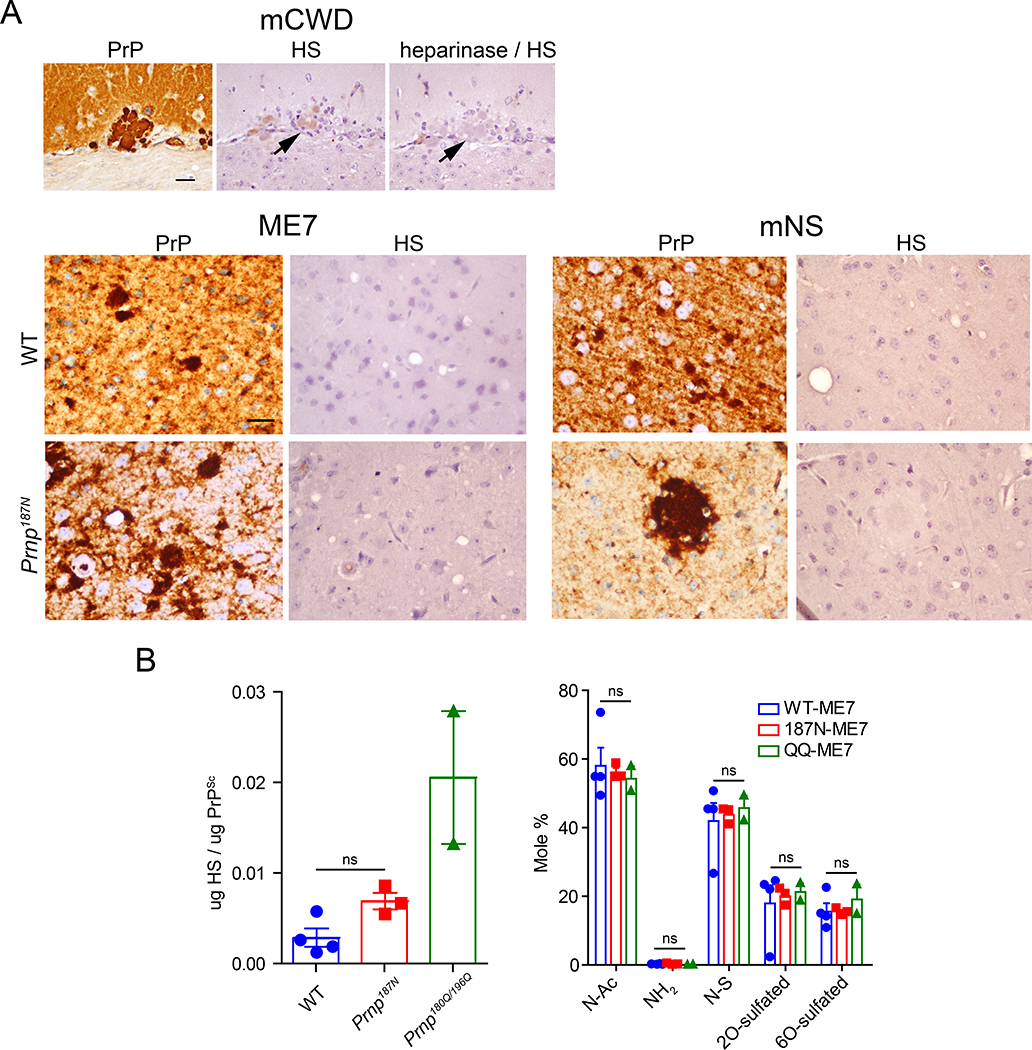

Triglycosylated PrPSc binds low levels of heparan sulfate

Glycosaminoglycans, including heparan sulfate (HS), co-localize with prion plaques in the brain [37, 58, 59] and accelerate prion conversion in vitro [71]. Unglycosylated PrP has a high heparin binding affinity and frequently forms HS-enriched congophilic plaques [54]. Since the PrP187N aggregates formed non-congophilic, plaque-like deposits in the ME7- and mNS-infected mice, we next tested whether these prions bind HS. Using the antibody 10E4 that binds an N-sulfated glucosamine residue, we immunolabelled ME7 and mNS prion-infected brain sections for HS (Fig 4A). Surprisingly, HS did not co-localize with the PrP plaque-like deposits in the Prnp187N-infected brain.

Figure 4. Heparan sulfate binding properties of PrP187N.

A. ME7 and mNS plaque-like deposits in the WT and Prnp187N brain sections do not label for HS using the anti-HS antibody 10E4, in contrast to amyloid plaques in the mCWD-infected brain (note that heparinase treatment ablates the HS labelling). B. Levels (left) and composition (right) of HS bound to PrP, as measured by LC-MS. Quantified are N-acetylated (N-Ac), unsubstituted glucosamine (NH2), N-sulfated (N-S), 2O-sulfated, and 6O-sulfated. Brain regions shown for HS stain in panel (A): ME7: cerebral cortex (WT) and thalamus (Prnp187N); mNS: cerebral cortex (WT and Prnp187N). Scale bar = 50 μm.

To confirm the lack of HS-PrP binding, we used liquid chromatography - mass spectrometry to quantify the HS levels and determine the HS composition bound to PrPSc from the ME7-infected mice (Fig 4B). We purified PrPSc from WT and Prnp187N brains, measured PrPSc levels compared to a dilution series of recombinant PrP by western blot (Fig. S3), assessed purity by silver stain, and then denatured and degraded the proteins by hydrolysis and enzyme digestion. HS was then purified and aniline tagged, and HS disaccharides were quantified by mass spectrometry compared to standards. We purified PrPSc from Prnp180Q,196Q brains, which have previously been shown to bind high levels of HS, to include as a positive control [54]. The amount of HS bound to PrPSc from Prnp187N brains was not significantly different from WT, and both contained less HS than the PrPSc purified from Prnp180Q,196Q brains. Additionally, the sulfation pattern of the HS bound to PrPSc in all three samples was not significantly different.

Collectively, this data indicates that ME7 and mNS prions in PrP187N mice form plaque-like deposits that are primarily GPI-anchored, Congo red negative, and HS-deficient, consistent with previous findings suggesting that HS does not bind highly glycosylated or GPI-anchored prions with high affinity, and with findings indicating that plaque-like structures observed in sporadic CJD maintain their GPI anchor [73].

Discussion

N-linked glycans stabilize proteins [15, 20, 44], including PrP, and slow prion fibril formation in vitro [7]. Here we tested whether the addition of a third glycan to PrP would slow prion disease progression in vivo, using Prnp187N knockin mice infected with four distinct prion strains. Our results instead demonstrate that Prnp187N mice remain highly susceptible to prions and show minimal changes in survival times, indicating that the additional glycan did not significantly hinder prion conversion.

The histopathology was markedly altered in the brains of Prnp187N mice infected with two of four prion strains, ME7 and mNS. PrPSc typically accumulates as a thin band along neuronal cell membranes and as small plaque-like aggregates in WT mice. Instead, ME7 and mNS prions formed an extensive assembly of PrPSc emerging from neuronal surfaces. These large plaque-like deposits differ from true amyloid plaques, as deposits were cell-associated, likely GPI-anchored, non-congophilic, and had low levels of bound HS. Notably, Prnp180Q,196Q mice expressing unglycosylated PrP develop a starkly different disease phenotype following ME7 and mNS infection, forming congophilic plaques composed of ADAM10-cleaved PrP highly enriched in HS [54]. Collectively, these results indicate that certain prions can switch between true amyloid plaques and cell-associated plaque-like deposits, depending on the number of N-linked glycans on PrPC (zero or three). The subtle amino acid differences are unlikely to underlie the strain switch, as Tuzi and colleagues found that ME7 prion-infected Prnp180T,196T knockin mice, which also express unglycosylated PrP, similarly formed amyloid plaques [64].

Prion glycosylation inversely correlates with PrPSc-bound heparan sulfate

Interestingly, early reports indicate that non-plaque deposits immunolabel minimally for HS, whereas amyloid plaques immunolabel strongly for HS in mice and in humans [1, 54, 59]. Indeed, previously we found that plaque formation and prion-bound HS levels measured by LC/MS were highly correlated [1, 54]. Here, none of the four strains in the Prnp187N mice formed plaques enriched in HS, as had occurred in the Prnp180Q,196Q mice. Although Prnp187N mice infected with two strains formed plaque-like aggregates, prion-bound HS levels were low, in agreement with previous findings that the N-linked glycans reduce the PrP binding affinity to sulfated glycosaminoglycans [54]. Collectively, these results, together with previous data in mice and in humans, reinforce the concept that glycans diminish PrP interaction with HS co-factors that could aid in scaffolding fibril formation, which may be limiting glycosylated prions to oligomers.

PrP glycans promote aggregation on membranes to form large plaque-like structures

GPI-anchoring of PrP hinders fibril formation, as mice expressing GPI-anchorless PrP consistently develop amyloid fibrils perivascularly following infection with diverse prion strains [2, 14]. These findings, together with observations in human genetic prion disease associated with GPI-anchorless PrP [22–24], have led to the suggestion that the GPI-anchor modulates fibril assembly of PrP, potentially through steric interference of fibril formation. To this end, a GPI-anchored form of the yeast prion, Sup35, expressed in neuronal cells formed membrane-bound, nonfibrillar aggregates, whereas GPI-anchorless Sup35 formed fibrils [36]. Interestingly, Sup35 accumulated in extracellular vesicles piling on the cell surface, which may be relevant to our findings of extensive plaque-like deposits of ME7 and mNS prions piling on neuronal cell membranes. Considering that prions can be converted on the plasma membrane or in multivesicular bodies (MVB) [11, 72], it is conceivable that ME7 and mNS prions accumulate in extracellular vesicles (EVs) (microvesicles or exosomes) that are trapped on the cell membrane. In this case, prions would retain the GPI-anchor, but would also be mobile and could transit through the interstitial and cerebrospinal fluid, accumulating periventricularly and adjacent to meninges, as we observed with PrPSc and CD9 co-localization. In support of this possibility, EVs have been shown to harbor prion aggregates and facilitate prion spread [21, 67].

Previously PrPSc was thought to retain the GPI-anchor, however, not all prions are exclusively GPI-anchored. For example, a plaque-forming prion, mCWD, is composed of monoglycosylated, shed PrP that lacks the GPI-anchor [1]. In humans with sporadic CJD, the presence of the GPI-anchor on plaque-like prion deposits has been controversial [40, 73], with recent biochemical evidence indicating that sCJD deposits are composed of GPI-anchored PrP [73]. Taken together, our data suggest that multiple N-linked glycans on PrP favor the conversion of GPI-anchored small or compact oligomers that bind poorly to HS, and accumulate as diffuse and plaque-like deposits associated with cells and at sites of interstitial and CSF efflux. Future studies to determine whether the plaque-like deposits originate from surface-associated microvesicles budding from the cell surface, from released MVB-derived exosomes, or from another source, will provide insight into subcellular prion conversion sites and the rapid dissemination of human and animal prions.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. ME7-infected Prnp187N brain immunolabelled for PrP reveals submeningeal PrPSc along the cortical surface (arrow). Also shown is a rare Congo red positive plaque adjacent to the lateral ventricle (arrowhead). Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure S2. Dual immunolabelling of brain sections for PrP (red) and CD9 (green) shows each single channel and the overlay. Note the co-localization of PrP and CD9 in the mNS- and ME7-infected Prnp187N brain, but not in the WT brain. Brain regions shown are: ME7: hippocampus (WT) and basal ganglia, adjacent to lateral ventricle (Prnp187N); mNS: hippocampus (WT) and hypothalamus (Prnp187N).

Figure S3. Western blot depicts the yield of purified PrPSc used for LC-MS. PrPSc was purified from WT, Prnp187N, and Prnp180Q,196Q prion-infected brain and quantified together with a dilution series of recombinant PrP via SDS-PAGE and western blotting. Note the molecular weight difference between the recombinant PrPC and the purified PrPSc, which is likely due to the lack of a GPI anchor in the recombinant protein.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jin Wang and Taylor Winrow for outstanding technical support, and the animal care staff at UC San Diego for excellent animal care. We thank the UC San Diego GlycoAnalytics Core for the mass spectrometry analysis, and Dr. Patricia Aguilar-Calvo for critical review of the manuscript. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants NS069566 (CJS), NS076896 (CJS), CJD Foundation (CJS and HCA), and the Werner-Otto-Stiftung (HCA). This work was also supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under K12HL141956 (JAC).

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Aguilar-Calvo P, Sevillano AM, Bapat J, Soldau K, Sandoval DR, Altmeppen HC, Linsenmeier L, Pizzo DP, Geschwind MD, Sanchez H et al. (2019) Shortening heparan sulfate chains prolongs survival and reduces parenchymal plaques in prion disease caused by mobile, ADAM10-cleaved prions. Acta Neuropathol: Doi 10.1007/s00401-019-02085-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilar-Calvo P, Xiao X, Bett C, Erana H, Soldau K, Castilla J, Nilsson KP, Surewicz WK, Sigurdson CJ (2017) Post-translational modifications in PrP expand the conformational diversity of prions in vivo. Sci Rep 7: 43295 Doi 10.1038/srep43295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguzzi A, Lakkaraju AK (2016) Cell Biology of Prions and Prionoids: A Status Report. Trends Cell Biol 26: 40–51 Doi 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baiardi S, Rossi M, Capellari S, Parchi P (2019) Recent advances in the histo-molecular pathology of human prion disease. Brain Pathol 29: 278–300 Doi 10.1111/bpa.12695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin MA, Stahl N, Reinders LG, Gibson BW, Prusiner SB, Burlingame AL (1990) Permethylation and tandem mass spectrometry of oligosaccharides having free hexosamine: analysis of the glycoinositol phospholipid anchor glycan from the scrapie prion protein. Anal Biochem 191: 174–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron GS, Hughson AG, Raymond GJ, Offerdahl DK, Barton KA, Raymond LD, Dorward DW, Caughey B (2011) Effect of glycans and the glycophosphatidylinositol anchor on strain dependent conformations of scrapie prion protein: improved purifications and infrared spectra. Biochemistry 50: 4479–4490 Doi 10.1021/bi2003907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosques CJ, Imperiali B (2003) The interplay of glycosylation and disulfide formation influences fibrillization in a prion protein fragment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 7593–7598 Doi 10.1073/pnas.1232504100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruce ME (1993) Scrapie strain variation and mutation. Br Med Bull 49: 822–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruce ME, Dickinson AG (1979) Biological stability of different classes of scrapie agent. In Slow Virus Infections of the Central Nervous System In: Prusiner SB, Hadlow WH (eds) In Slow Virus Infections of the Central Nervous System. New York: Academic Press, City, pp 71–86 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke CM, Walsh DJ, Steele AD, Agrimi U, Di Bari MA, Watts JC, Supattapone S (2019) Full restoration of specific infectivity and strain properties from pure mammalian prion protein. PLoS Pathog 15: e1007662 Doi 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caughey B, Raymond GJ, Ernst D, Race RE (1991) N-terminal truncation of the scrapie-associated form of PrP by lysosomal protease(s): implications regarding the site of conversion of PrP to the protease-resistant state. J Virol 65: 6597–6603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caughey BW, Dong A, Bhat KS, Ernst D, Hayes SF, Caughey WS (1991) Secondary structure analysis of the scrapie-associated protein PrP 27–30 in water by infrared spectroscopy [published erratum appears in Biochemistry 1991 Oct 29;30(43):10600]. Biochemistry 30: 7672–7680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chesebro B, Race R, Wehrly K, Nishio J, Bloom M, Lechner D, Bergstrom S, Robbins K, Mayer L, Keith JM (1985) Identification of scrapie prion protein-specific mRNA in scrapie-infected and uninfected brain. Nature 315: 331–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chesebro B, Trifilo M, Race R, Meade-White K, Teng C, LaCasse R, Raymond L, Favara C, Baron G, Priola S et al. (2005) Anchorless prion protein results in infectious amyloid disease without clinical scrapie. Science 308: 1435–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Culyba EK, Price JL, Hanson SR, Dhar A, Wong CH, Gruebele M, Powers ET, Kelly JW (2011) Protein native-state stabilization by placing aromatic side chains in N-glycosylated reverse turns. Science 331: 571–575 Doi 10.1126/science.1198461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deleault NR, Harris BT, Rees JR, Supattapone S (2007) Formation of native prions from minimal components in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 9741–9746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickinson AG (1976) Scrapie in sheep and goats. Front Biol 44: 209–241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickinson AW, Outram GW, Taylor DM, Foster JD (1986) Further evidence that scrapie agent has an independent genome In: In Court LA, Dormont D, Brown P, Kingsbury DT (eds) Unconventional Virus Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Commisariat à l’Energie Atomique, Paris, France, City, pp 446–460 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Endo T, Groth D, Prusiner SB, Kobata A (1989) Diversity of oligosaccharide structures linked to asparagines of the scrapie prion protein. Biochemistry 28: 8380–8388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng X, Wang X, Han B, Zou C, Hou Y, Zhao L, Li C (2018) Design of Glyco-Linkers at Multiple Structural Levels to Modulate Protein Stability. J Phys Chem Lett 9: 4638–4645 Doi 10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b01570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fevrier B, Vilette D, Archer F, Loew D, Faigle W, Vidal M, Laude H, Raposo G (2004) Cells release prions in association with exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 9683–9688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghetti B, Piccardo P, Frangione B, Bugiani O, Giaccone G, Young K, Prelli F, Farlow MR, Dlouhy SR, Tagliavini F (1996) Prion Protein Amyloidosis. Brain Pathol 6: 127–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghetti B, Piccardo P, Frangione B, Bugiani O, Giaccone G, Young K, Prelli F, Farlow MR, Dlouhy SR, Tagliavini F (1996) Prion Protein Hereditary Amyloidosis - Parenchymal and Vascular. Semin Virol 7: 189–200 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghetti B, Piccardo P, Spillantini MG, Ichimiya Y, Porro M, Perini F, Kitamoto T, Tateishi J, Seiler C, Frangione B et al. (1996) Vascular variant of prion protein cerebral amyloidosis with tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles: the phenotype of the stop codon 145 mutation in PRNP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 744–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghetti B, Piccardo P, Zanusso G (2018) Dominantly inherited prion protein cerebral amyloidoses - a modern view of Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker. Handb Clin Neurol 153: 243–269 Doi 10.1016/b978-0-444-63945-5.00014-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenlee JJ, Greenlee MH (2015) The transmissible spongiform encephalopathies of livestock. ILAR journal 56: 7–25 Doi 10.1093/ilar/ilv008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Group. W (2020) GLYCAM Web. Complex Carbohydrate Research Center http://glycam.org

- 28.Iwasaki Y, Kato H, Ando T, Mimuro M, Kitamoto T, Yoshida M (2017) MM1-type sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with 1-month total disease duration and early pathologic indicators. Neuropathology 37: 420–425 Doi 10.1111/neup.12379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jucker M, Walker LC (2018) Propagation and spread of pathogenic protein assemblies in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci 21: 1341–1349 Doi 10.1038/s41593-018-0238-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katorcha E, Baskakov IV (2017) Analyses of N-linked glycans of PrP(Sc) revealed predominantly 2,6-linked sialic acid residues. FEBS J 284: 3727–3738 Doi 10.1111/febs.14268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim MO, Takada LT, Wong K, Forner SA, Geschwind MD (2018) Genetic PrP Prion Diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10: Doi 10.1101/cshperspect.a033134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovacs GG (2019) Molecular pathology of neurodegenerative diseases: principles and practice. J Clin Pathol 72: 725–735 Doi 10.1136/jclinpath-2019-205952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawrence R, Brown JR, Al-Mafraji K, Lamanna WC, Beitel JR, Boons GJ, Esko JD, Crawford BE (2012) Disease-specific non-reducing end carbohydrate biomarkers for mucopolysaccharidoses. Nat Chem Biol 8: 197–204 Doi nchembio.766 [pii] 10.1038/nchembio.766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawrence R, Olson SK, Steele RE, Wang L, Warrior R, Cummings RD, Esko JD (2008) Evolutionary differences in glycosaminoglycan fine structure detected by quantitative glycan reductive isotope labeling. J Biol Chem 283: 33674–33684 Doi 10.1074/jbc.M804288200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linsenmeier L, Mohammadi B, Wetzel S, Puig B, Jackson WS, Hartmann A, Uchiyama K, Sakaguchi S, Endres K, Tatzelt J et al. (2018) Structural and mechanistic aspects influencing the ADAM10-mediated shedding of the prion protein. Mol Neurodegener 13: 18 Doi 10.1186/s13024-018-0248-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall KE, Offerdahl DK, Speare JO, Dorward DW, Hasenkrug A, Carmody AB, Baron GS (2014) Glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchoring directs the assembly of Sup35NM protein into non-fibrillar, membrane-bound aggregates. J Biol Chem 289: 12245–12263 Doi 10.1074/jbc.M114.556639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McBride PA, Wilson MI, Eikelenboom P, Tunstall A, Bruce ME (1998) Heparan sulfate proteoglycan is associated with amyloid plaques and neuroanatomically targeted PrP pathology throughout the incubation period of scrapie-infected mice. Exp Neurol 149: 447–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitra N, Sinha S, Ramya TN, Surolia A (2006) N-linked oligosaccharides as outfitters for glycoprotein folding, form and function. Trends Biochem Sci 31: 156–163 Doi 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nilsson KP, Joshi-Barr S, Winson O, Sigurdson CJ (2010) Prion strain interactions are highly selective. J Neurosci 30: 12094–12102 Doi 30/36/12094 [pii] 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2417-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Notari S, Strammiello R, Capellari S, Giese A, Cescatti M, Grassi J, Ghetti B, Langeveld JP, Zou WQ, Gambetti P et al. (2008) Characterization of truncated forms of abnormal prion protein in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Biol Chem 283: 30557–30565 Doi 10.1074/jbc.M801877200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oesch B, Westaway D, Walchli M, McKinley MP, Kent SB, Aebersold R, Barry RA, Tempst P, Teplow DB, Hood LE et al. (1985) A cellular gene encodes scrapie PrP 27–30 protein. Cell 40: 735–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peretz D, Scott MR, Groth D, Williamson RA, Burton DR, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB (2001) Strain-specified relative conformational stability of the scrapie prion protein. Protein Sci 10: 854–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polymenidou M, Moos R, Scott M, Sigurdson C, Shi YZ, Yajima B, Hafner-Bratkovic I, Jerala R, Hornemann S, Wuthrich K et al. (2008) The POM monoclonals: a comprehensive set of antibodies to non-overlapping prion protein epitopes. PLoS One 3: e3872 Doi 10.1371/journal.pone.0003872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price JL, Culyba EK, Chen W, Murray AN, Hanson SR, Wong CH, Powers ET, Kelly JW (2012) N-glycosylation of enhanced aromatic sequons to increase glycoprotein stability. Biopolymers 98: 195–211 Doi 10.1002/bip.22030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Price JL, Powers DL, Powers ET, Kelly JW (2011) Glycosylation of the enhanced aromatic sequon is similarly stabilizing in three distinct reverse turn contexts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 14127–14132 Doi 10.1073/pnas.1105880108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prusiner SB (1982) Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 216: 136–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prusiner SB, Scott M, Foster D, Pan KM, Groth D, Mirenda C, Torchia M, Yang SL, Serban D, Carlson GA et al. (1990) Transgenetic studies implicate interactions between homologous PrP isoforms in scrapie prion replication. Cell 63: 673–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raymond GJ, Chabry J (2004) Methods and Tools in Biosciences and Medicine. In: Lehmann S, Grassi J (eds) Techniques in Prion Research. Birkhäuser, Basel, City, pp 16–26 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riek R, Hornemann S, Wider G, Billeter M, Glockshuber R, Wuthrich K (1996) Nmr Structure of the Mouse Prion Protein Domain Prp(121–231). Nature 382: 180–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rudd PM, Endo T, Colominas C, Groth D, Wheeler SF, Harvey DJ, Wormald MR, Serban H, Prusiner SB, Kobata A et al. (1999) Glycosylation differences between the normal and pathogenic prion protein isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 13044–13049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudd PM, Wormald MR, Wing DR, Prusiner SB, Dwek RA (2001) Prion glycoprotein: structure, dynamics, and roles for the sugars. Biochemistry 40: 3759–3766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandberg MK, Al-Doujaily H, Sharps B, Clarke AR, Collinge J (2011) Prion propagation and toxicity in vivo occur in two distinct mechanistic phases. Nature 470: 540–542 Doi 10.1038/nature09768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Selkoe DJ (1991) The molecular pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 6: 487–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sevillano AM, Aguilar-Calvo P, Kurt TD, Lawrence JA, Soldau K, Nam TH, Schumann T, Pizzo DP, Nystrom S, Choudhury B et al. (2020) Prion protein glycans reduce intracerebral fibril formation and spongiosis in prion disease. J Clin Invest: Doi 10.1172/jci131564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sigurdson CJ, Manco G, Schwarz P, Liberski P, Hoover EA, Hornemann S, Polymenidou M, Miller MW, Glatzel M, Aguzzi A (2006) Strain fidelity of chronic wasting disease upon murine adaptation. J Virol 80: 12303–12311 Doi 10.1128/jvi.01120-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sim VL, Caughey B (2008) Ultrastructures and strain comparison of under-glycosylated scrapie prion fibrils. Neurobiol Aging: Doi S0197–4580(08)00065–1 [pii] 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Snow AD, Kisilevsky R, Willmer J, Prusiner SB, DeArmond SJ (1989) Sulfated glycosaminoglycans in amyloid plaques of prion diseases. Acta Neuropathol 77: 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Snow AD, Kisilevsky R, Willmer J, Prusiner SB, DeArmond SJ (1989) Sulfated glycosaminoglycans in amyloid plaques of prion diseases. Acta Neuropathol Berl 77: 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Snow AD, Wight TN, Nochlin D, Koike Y, Kimata K, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB (1990) Immunolocalization of heparan sulfate proteoglycans to the prion protein amyloid plaques of Gerstmann-Straussler syndrome, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and scrapie. Lab Invest 63: 601–611 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Srivastava S, Katorcha E, Daus ML, Lasch P, Beekes M, Baskakov IV (2017) Sialylation Controls Prion Fate in Vivo. J Biol Chem 292: 2359–2368 Doi 10.1074/jbc.M116.768010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Srivastava S, Katorcha E, Makarava N, Barrett JP, Loane DJ, Baskakov IV (2018) Inflammatory response of microglia to prions is controlled by sialylation of PrP(Sc). Sci Rep 8: 11326 Doi 10.1038/s41598-018-29720-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stahl N, Baldwin MA, Prusiner SB (1991) Electrospray mass spectrometry of the glycosylinositol phospholipid of the scrapie prion protein. Cell Biol Int Rep 15: 853–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stohr J, Weinmann N, Wille H, Kaimann T, Nagel-Steger L, Birkmann E, Panza G, Prusiner SB, Eigen M, Riesner D (2008) Mechanisms of prion protein assembly into amyloid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 2409–2414 Doi 10.1073/pnas.0712036105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tuzi NL, Cancellotti E, Baybutt H, Blackford L, Bradford B, Plinston C, Coghill A, Hart P, Piccardo P, Barron RM et al. (2008) Host PrP glycosylation: a major factor determining the outcome of prion infection. PLoS Biol 6: e100 Doi 07-PLBI-RA-2655 [pii] 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vaquer-Alicea J, Diamond MI (2019) Propagation of Protein Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Annu Rev Biochem 88: 785–810 Doi 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-045049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Varki A (2017) Biological roles of glycans. Glycobiology 27: 3–49 Doi 10.1093/glycob/cww086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vella LJ, Sharples RA, Lawson VA, Masters CL, Cappai R, Hill AF (2007) Packaging of prions into exosomes is associated with a novel pathway of PrP processing. J Pathol 211: 582–590 Doi 10.1002/path.2145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wadsworth JDF, Joiner S, Hill AF, Campbell TA, Desbruslais M, Luthert PJ, Collinge J. (2001) Tissue distribution of protease resistant prion protein in variant CJD using a highly sensitive immuno-blotting assay. Lancet 358: 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang F, Wang X, Yuan CG, Ma J (2010) Generating a prion with bacterially expressed recombinant prion protein. Science 327: 1132–1135 Doi science.1183748 [pii] 10.1126/science.1183748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weerapana E, Imperiali B (2006) Asparagine-linked protein glycosylation: from eukaryotic to prokaryotic systems. Glycobiology 16: 91r–101r Doi 10.1093/glycob/cwj099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wong C, Xiong LW, Horiuchi M, Raymond L, Wehrly K, Chesebro B, Caughey B (2001) Sulfated glycans and elevated temperature stimulate PrP(Sc)-dependent cell-free formation of protease-resistant prion protein. EMBO J 20: 377–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yim YI, Park BC, Yadavalli R, Zhao X, Eisenberg E, Greene LE (2015) The multivesicular body is the major internal site of prion conversion. J Cell Sci 128: 1434–1443 Doi 10.1242/jcs.165472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zanusso G, Fiorini M, Ferrari S, Meade-White K, Barbieri I, Brocchi E, Ghetti B, Monaco S (2014) Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker disease and “anchorless prion protein” mice share prion conformational properties diverging from sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Biol Chem 289: 4870–4881 Doi 10.1074/jbc.M113.531335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zerr I, Parchi P (2018) Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Handb Clin Neurol 153: 155–174 Doi 10.1016/b978-0-444-63945-5.00009-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zerr I, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Giese A, Bodemer M, Schroter A, Henkel K, Tschampa HJ, Windl O, Pfahlberg A, Steinhoff BJ et al. (2000) Current clinical diagnosis in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: identification of uncommon variants. Ann Neurol 48: 323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. ME7-infected Prnp187N brain immunolabelled for PrP reveals submeningeal PrPSc along the cortical surface (arrow). Also shown is a rare Congo red positive plaque adjacent to the lateral ventricle (arrowhead). Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure S2. Dual immunolabelling of brain sections for PrP (red) and CD9 (green) shows each single channel and the overlay. Note the co-localization of PrP and CD9 in the mNS- and ME7-infected Prnp187N brain, but not in the WT brain. Brain regions shown are: ME7: hippocampus (WT) and basal ganglia, adjacent to lateral ventricle (Prnp187N); mNS: hippocampus (WT) and hypothalamus (Prnp187N).

Figure S3. Western blot depicts the yield of purified PrPSc used for LC-MS. PrPSc was purified from WT, Prnp187N, and Prnp180Q,196Q prion-infected brain and quantified together with a dilution series of recombinant PrP via SDS-PAGE and western blotting. Note the molecular weight difference between the recombinant PrPC and the purified PrPSc, which is likely due to the lack of a GPI anchor in the recombinant protein.