Abstract

ANO1 (TMEM16A) is a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel (CaCC) expressed in peripheral somatosensory neurons that are activated by painful (noxious) stimuli. These neurons also express the Ca2+-permeable channel and noxious heat sensor TRPV1, which can activate ANO1. Here, we revealed an intricate mechanism of TRPV1-ANO1 channel coupling in rat dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. Simultaneous optical monitoring of CaCC activity and Ca2+ dynamics revealed that the TRPV1 ligand capsaicin activated CaCCs. However, depletion of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ stores reduced capsaicin-induced Ca2+ increases and CaCC activation, suggesting that ER Ca2+ release contributed to TRPV1-induced CaCC activation. ER store depletion by plasma membrane-localized TRPV1 channels was demonstrated with an ER-localized Ca2+ sensor in neurons exposed to a cell-impermeable TRPV1 ligand. Proximity ligation assays established that ANO1, TRPV1 and the IP3 receptor IP3R1 were often found in close proximity to each other. Stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) confirmed the close association between all three channels in DRG neurons. Together, our data reveal the existence of ANO1-containing multi-channel nanodomains in DRG neurons and suggest that coupling between TRPV1 and ANO1 requires ER Ca2+ release, which may be necessary to enhance ANO1 activation.

Introduction

Ca2+ activated Cl− channels (CaCCs) are important regulators of epithelial transport, smooth muscle contraction and neuronal excitability (reviewed in (1–4)). The molecular identity of CaCCs remained elusive until 2008, when 3 groups identified ANO1 (TMEM16A), a member of the anoctamin (TMEM16) family of transmembrane proteins, as a bona fide CaCC (5–7). Functional expression of ANO1 has been confirmed in peripheral damage-sensing (nociceptive) neurons (7–10). In contrast to most adult CNS neurons, peripheral somatosensory neurons accumulate relatively high intracellular [Cl−]i, sufficient to maintain their Cl− equilibrium potential (ECl) at voltages more positive than the threshold for action potential firing (8, 11). Therefore, activation of ANO1-mediated CaCCs in these cells can increase excitability and trigger or potentiate nociception. Furthermore, the Na+, K+ and Cl− cotransporter NKCC1 is upregulated in sensory neurons during nerve injury (12), which leads to further Cl− accumulation and potentially even greater excitatory effects of ANO1 currents.

ANO1 channels possess an intrinsically low Ca2+ sensitivity with an EC50 in the range of 2–5 μM at −60 mV (7, 13). This low sensitivity may be due to the unusual location of the Ca2+ binding site of ANO1, which localizes to a domain between the α6 and α8 transmembrane helices situated within the lipid bilayer (14). The Ca2+ sensitivity of ANO1 is voltage dependent such that it increases with depolarization (13, 15); for example, an EC50 of 0.4 μM is measured at +100 mV. Nevertheless, at the resting membrane potential of sensory neurons of ~−60 mV (16–18), [Ca2+]i of >1–2 μM is required to activate ANO1. Global Ca2+ levels in the cytosol do not normally reach micromolar concentrations, and therefore, to enable reliable ANO1 activation, localized, high-intensity Ca2+ signals are required (1, 19–21). Intriguingly, in sensory neurons from dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons, ANO1 is found in close proximity to G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), such as the bradykinin (BK) B2 receptor (B2R) and the protease activated receptor-2 (PAR2) on the plasma membrane (PM), and physically coupled with endoplasmic reticulum (ER) localized IP3 receptors (IP3Rs), forming a junctional ER-PM complex (19). We have shown that upon stimulation of such Gq/11-coupled GPCRs (GqPCRs), IP3 generation activates IP3Rs, which, in turn, leads to Ca2+ release from the ER and ANO1 activation. Due to the proximity between the components of the junctional complex, local Ca2+ elevations, which reach up to 50–75 μM at the mouth of IP3R channel (22, 23), are sufficient to enable ANO1 activation (19). BK, proteases and other relevant GPCR ligands are released upon tissue inflammation and contribute to inflammatory pain and itch, in part through the GPCR-induced activation of ANO1/CaCCs and depolarization of nociceptive afferents (8, 24–27). Localization of ANO1 channels to ER-PM junctional nanodomains may also serve the function of shielding ANO1 channels from activation by other, non-colocalized Ca2+ signals, such as those generated by voltage-gated Ca2+ channels during action potential firing (1, 19, 28).

ANO1 in DRG neurons can also be activated by noxious heat at a similar temperature range to the ‘canonical’ noxious heat sensor TRPV1 (9, 10). In addition, TRPV1 is another major mediator of inflammatory pain, and activation of TRPV1 channels is sensitized by BK and PAR2 (25, 29). Furthermore, opening of TRPV1 channels activates ANO1 in sensory neurons (10). The latter study suggested that ANO1 and TRPV1 are directly coupled, with Ca2+ entry through TRPV1 providing the local Ca2+ elevation that allows ANO1 activation (10). Notably, the Ca2+ influx through TRPV1 amounts to no more than ~10% of the total TRPV1 cation current (30). On the other hand, TRPV1 activates Ca2+-sensitive phospholipase C (PLCδ) and induces Ca2+ release from the ER in the absence of prior stimulation of GqPCRs (31). Thus, the question arises: Is direct Ca2+ influx through the TRPV1 channel pore sufficient to fully activate ANO1 in sensory neurons or are other Ca2+ sources also involved or obligatory? Using live-imaging approaches, patch-clamp electrophysiology, proximity ligation and a super-resolution microscopy method, we demonstrated that a substantial fraction of ANO1 and TRPV1 channels were found in junctional nanodomains in small-diameter nociceptors and that TRPV1-mediated Ca2+ release from ER-resident IP3Rs was a major factor in functional TRPV1-ANO1 coupling.

Results

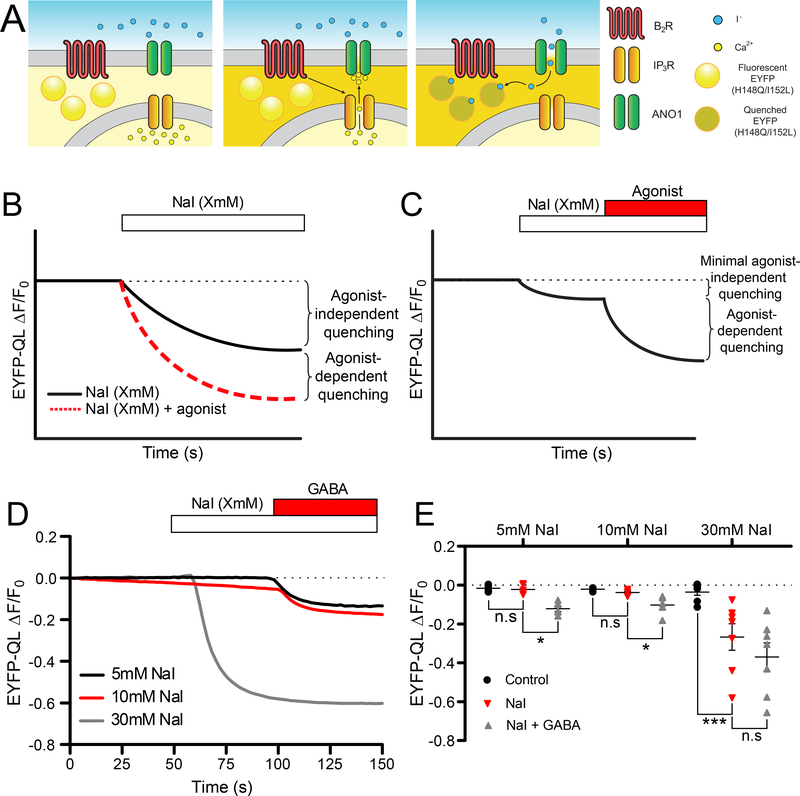

Single-cell fluorescence imaging can measure currents through CaCCs

Imaging of halide-sensitive enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) mutants has been previously used to monitor Cl− channel activity (32–34). The method is based on the permeability of most anion channels to iodide ions (I−), which, when added to the extracellular solution, quenches EYFP fluorescence in a manner dependent on anion channel opening. However, previous applications of this technique, including a single-cell approach developed by us (19), do not allow correlation of intracellular Ca2+ dynamics with I− influx. Furthermore, the agonist-independent quenching complicates quantification and masks the response obtained by agonists. Here we developed a triple-wavelength imaging approach to simultaneously monitor halide-sensitive EYFP quenching and ratiometric fura-2 Ca2+ imaging (Fig. 1A). DRG neurons abundantly express GABAA Cl− channels (35–37); thus, we used GABA responses from cultured rat DRG neurons transfected with the halide-sensitive mutant EYFP H148Q/I152L (EYFP-QL) to optimize the extracellular I− concentration and minimize agonist-independent quenching (Fig. 1B–E). Equimolar replacement of 5–30 mM NaCl with NaI revealed that 5 mM NaI offered the lowest rate of agonist-independent EYFP-QL quenching while providing sufficient dynamic range for the reliable detection of Cl− channel opening.

Figure 1. Optical interrogation of Cl− channel activity in DRG neurons.

(A) Schematic of the dual imaging protocol. DRG neurons are transfected with EYFP (H148Q/I152L); NaI (I−) is added to the extracellular solutions. Upon stimulation of GPCRs such as the bradykinin receptor B2R, Ca2+ is released from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) through the IP3R. This rise in intracellular Ca2+ is detected by fura-2 (depicted as brightening of cytosol in the middle and right panels). Activation of ANO1 channels by released Ca2+ results in I− influx, which, in turn induces quenching of the EYFP-QL fluorescence (right panel). (B) Schematic of expected EYFP (H148Q/I152L) quenching in response to ANO1-mediated I− influx (30 mM extracellular NaI; based on (19)). (C) Schematic of the optimized protocol developed in this study. The concentration of NaI is reduced in steps to develop a protocol with minimal agonist-independent quenching and sufficient dynamic range. (D) Representative traces of EYFP (H148Q/I152L) fluorescence quenching produced by 5 mM (black trace), 10 mM (red trace) and 30 mM (grey trace) extracellular NaI and subsequently added GABA (100 μM). (E) Scatter plots summarizing experiments similar to those shown in (D); 5 mM: n=5 neurons, 10 mM: n=5 neurons and 30 mM: n=7 neurons. Quenching produced after standard bath solution application (black circle), NaI application (red triangle) and NaI and GABA (100 μM) application (grey triangles). Asterisks denote the following: *p<0.05 and ***p<0.001 (paired t-test); n.s, not significant.

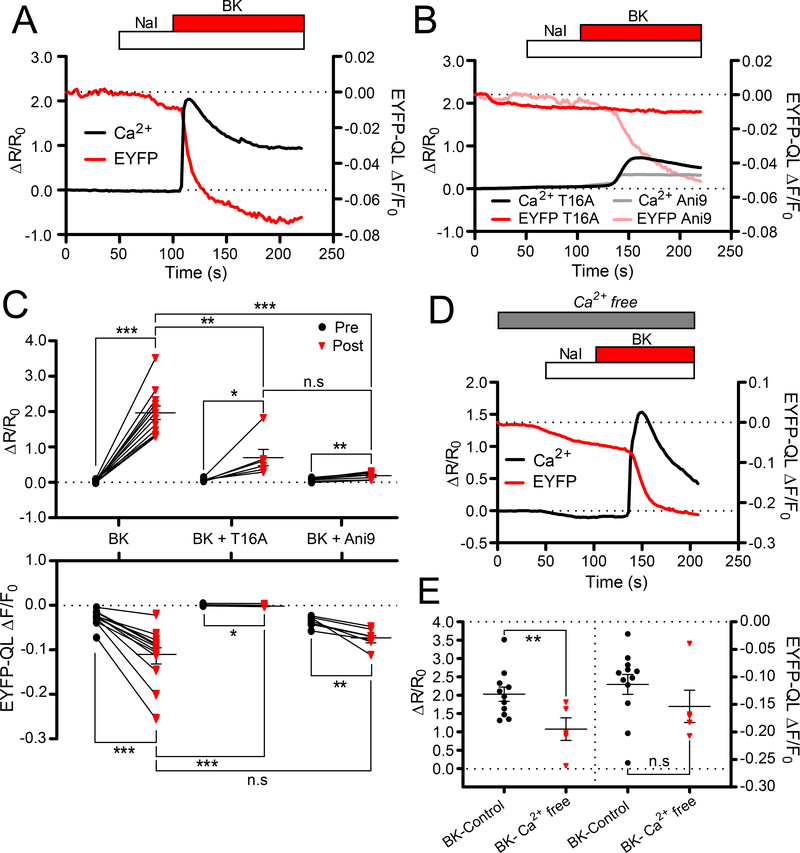

We then performed simultaneous halide and Ca2+ imaging of DRG neurons transfected with EYFP-QL and loaded with fura-2AM. B2R receptors were stimulated by bath-application of BK (250 nM) in the presence of 5 mM NaI while performing triple-wavelength excitation (340/380/488nm). Consistent with our previous study (19), BK induced robust transient [Ca2+]i rises which were temporally correlated with the EYFP-QL fluorescence quenching (Fig. 2A, B). In contrast to the Ca2+ rises, which were transient in nature, the EYFP-QL quenching did not normally recover within the period of observation (reflecting that once I− is taken up by a cell during CaCC activation, it is not easily extruded under our experimental conditions). The mean amplitude of the peak fura-2 Ca2+ signal (ΔR/R0) and the mean drop in the normalized EYFP-QL fluorescence (ΔF/F0) induced by BK are shown in Fig. 2C (left).

Figure 2. All-optical demonstration of coupling of CaCC activation to IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release.

(A, B) Representative traces showing Ca2+ rises and concurrent EYFP-QL fluorescence quenching in small-diameter DRG neurons transfected with EYFP-QL and loaded with fura-2AM in response to BK (250 nM) application in the absence (A) or presence (B) of ANO1 inhibitors, T16A-inhA01 (50 μM) or Ani9 (500 nM). (C) Scatter plots summarizing experiments similar to those shown in (A); BK: n=12 neurons, (B); T16A-inhA01: n=6 neurons and Ani9: n=7 neurons. (D) Representative trace showing fura-2 and EYFP-QL responses to BK application in DRG neurons when Ca2+ was omitted from the extracellular solutions. (E) Comparison between the data for BK application with (n=12 neurons) and without extracellular Ca2+ (n=5 neurons). In C and E, asterisks denote the following: *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001; n.s, not significant (paired or unpaired t-test, as appropriate).

To confirm that this quenching was indeed mediated by ANO1 and not another Cl− channel flux, transfected cells were preincubated and perfused with two ANO1 inhibitors, T16A-inhA01 and Ani9 (38). In the presence of T16A-inhA01 (50 μM), EYFP-QL quenching induced by BK was abolished despite the presence of Ca2+ transients (Fig. 2C). Ani9 (500 nM) also inhibited BK-induced quenching, although to a lesser extent. The BK-induced [Ca2+]i rises were smaller in the presence of both ANO1 inhibitors, compared to control conditions (Fig. 2C). This observation is consistent with the hypothesis that ANO1 is not only a target of the Ca2+ signals, but may also facilitate ER Ca2+ release because of structural interactions between the PM and the ER (28). Hence, both T16A-inhA01 and Ani9 may interfere with this process. However, BK application still induced measurable rises in [Ca2+]i in the presence of T16A-inhA01 and Ani9, whereas EYFP-QL quenching was either abolished (T16A-inhA01) or significantly reduced (Ani9). This indicates that our imaging approach allows reliable, all-optical measurement of ANO1-mediated CaCCs and concurrent Ca2+ dynamics in individual DRG neurons.

TRPV1-ANO1 coupling requires Ca2+ release from the ER

ANO1 activation is coupled to intracellular Ca2+ release from IP3Rs in DRG neurons (19). To confirm this coupling using our imaging approach, BK was applied in the absence of Ca2+ in the extracellular bath solutions (Fig. 2D). The amplitude of EYFP-QL quenching was not affected by the removal of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 2E), despite a significantly lower induced [Ca2+] rise, compared to control conditions. This finding suggested that even though Ca2+ influx through PM Ca2+ channels contributed to the global Ca2+ rises induced by BK (8), it was the ER Ca2+ release that specifically activated ANO1/CaCC following B2R activation. Indeed, as shown previously (19), Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) is poorly-coupled to ANO1 activation in DRG neurons. To verify this finding using our imaging approach, we stimulated Ca2+ influx through VGCCs by depolarizing neurons with an extracellular solution containing 50 mM KCl (fig. S1A, B). The majority (15/23 or 65%) of DRG neurons did not respond to 50 mM K+ with any measurable EYFP-QL quenching, despite strong rises in [Ca2+]i. The remaining 35% (8/23) neurons did display quenching (fig. S1A, B). However, significant EYFP-QL quenching induced by 50 mM KCl was observed in some DRG neurons in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ as well (fig. S1C, D). Because [Ca2+]i rises were not recorded under these conditions, we conclude that depolarization-induced quenching observed in the minority of DRG neurons was likely not CaCC-related. In summary, our data (Fig. 2, A to E and fig. S1, A to D) established a reliable optical approach for measuring CaCC activation in DRG neurons and confirmed preferential coupling of ANO1/CaCC to IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER rather than Ca2+ influx through PM Ca2+ channels in DRG neurons.

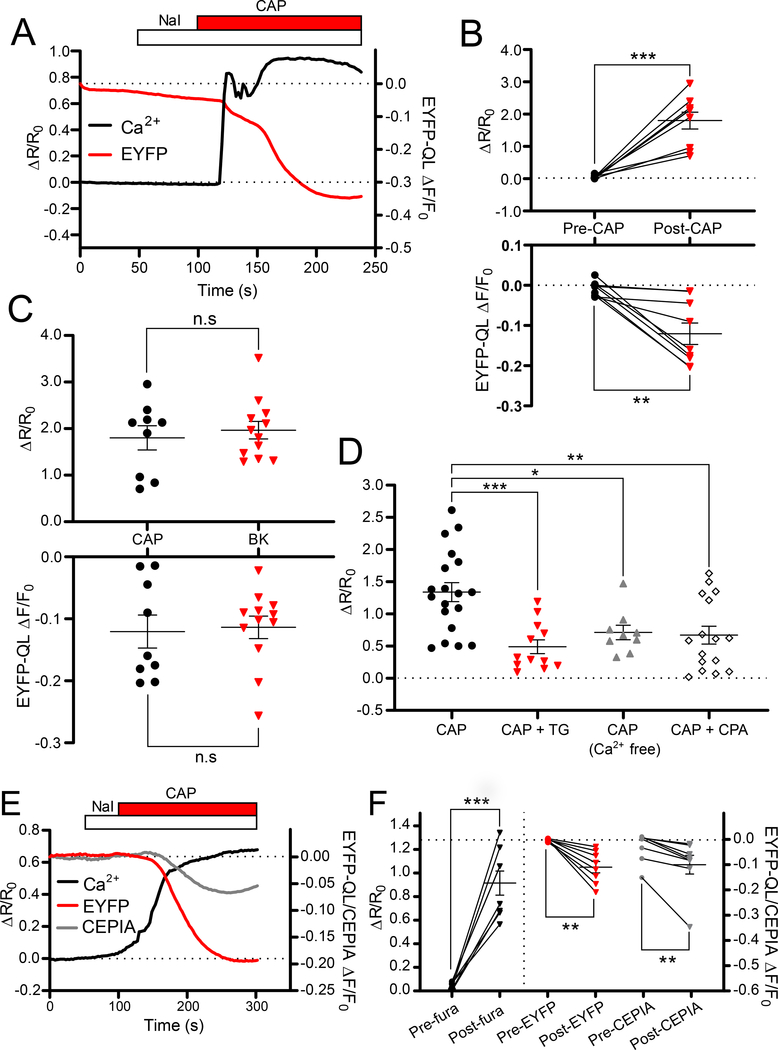

TRPV1 activation in DRG neurons and in heterologous expression systems results in activation of ANO1; furthermore, ANO1 potentiates TRPV1-induced depolarization in vitro and the sensory response to heat in vivo (10). ANO1 is itself a heat-sensitive channel, with its thermo-sensitivity modulated by Ca2+ (9). Moreover, both ANO1 and TRPV1 channels are targeted by BK signals (8, 19, 39). Thus, elucidating the relationships between these two channels may reveal aspects of thermal sensitivity and inflammatory pain mechanisms. Takayama and colleagues suggested that TRPV1 and ANO1 interact physically and that Ca2+ influx through TRPV1 is the main mechanism of coupled ANO1 activation. However, TRPV1 is a nonselective cation channel and under physiological conditions conducts mostly Na+ currents with Ca2+ influx contributing only 7–10% of the overall current (30). On the other hand, TRPV1 activation in DRG neurons induces PLC activation and ER Ca2+ release (31). Given the coupling of ANO1 to ER-released Ca2+, we used our optical recording approach to test if this Ca2+ source contributed to TRPV1-ANO1 coupling as well. TRPV1 activation with 1 μM capsaicin induced significant EYFP-QL quenching (Fig. 3A, B), which correlated with intracellular Ca2+ rises (Fig. 3A). Both the capsaicin-induced EYFP-QL quenching and Ca2+ transients were comparable to those induced by BK (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. ER Ca2+ release is required for the TRPV1-mediated activation of CaCC.

(A) Representative trace showing a Ca2+ rise and a concurrent EYFP-QL fluorescence quenching in a small-diameter DRG neuron transfected with EYFP-QL and loaded with fura-2AM in response to capsaicin (1 μM) application. (B) Scatter plots summarizing experiments similar to those shown in (A); n=9 neurons. (C) Comparisons for the fura-2 ratiometric Ca2+ measurement and EYFP-QL fluorescence quenching in response to capsaicin and BK application. (D) Summary of fura-2 Ca2+ imaging experiments in which capsaicin was applied either under control conditions (n=19 neurons), in the presence of thapsigargin (TG; 1μM; n=12 neurons), with no extracellular Ca2+ (n=9 neurons), or in the presence of cyclopiazonic acid (CPA; 1μM; n=16 neurons). (E) Representative traces showing a response to capsaicin in triple imaging experiments, where fura-2 Ca2+ levels (black trace), EYFP-QL fluorescence quenching (red trace) and ER-Ca2+ levels using red-CEPIA (grey trace) were simultaneously monitored in EYFP-QL and red-CEPIA co-transfected DRG neurons. (F) Scatter plots summarizing experiments similar to those shown in (E), n=8 neurons. In B-F, asterisks denote the following: *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001; n.s, not significant (B, F: paired t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test; C: unpaired t-test; D: one-way ANOVA).

Next, we tested if Ca2+ release from the ER contributed to TRPV1-induced ANO1 activation. As a first step, we measured capsaicin-induced Ca2+ transients in untransfected DRG neurons after ER store depletion produced by inhibition of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase by either thapsigargin (TG; 1 μM) or cyclopiazonic acid (CPA;1 μM; Fig. 3D, fig. S2A). Consistent with a previous report (31), Ca2+ transients were significantly reduced in the presence of both drugs. However, after removal of Ca2+ from the extracellular bath solutions, capsaicin still produced Ca2+ signals (Fig. 3D, fig. S2A). These were significantly smaller as compared to control conditions, yet clearly identifiable. These initial experiments indicate that TRPV1 can induce sizeable Ca2+ release from the internal stores, which contributes approximately one half of the global Ca2+ signal measured by fura-2.

Next, we used triple-wavelength imaging to investigate the effect of store depletion on ANO1 activation, as measured with EYFP-QL quenching. Depletion of ER Ca2+ stores with TG reduced not only Ca2+ transients after capsaicin application but also EYFP-QL quenching (fig. S2B, C). We also applied capsaicin in Ca2+-free extracellular solution and using our triple wavelength imaging approach determined that both Ca2+ transients and significant EYFP-QL quenching were still present (fig. S3A, B). These results provide further support for our proposal that CaCC activation through TRPV1 requires the ER component. We also tested whether ER Ca2+ ‘leak’ could induce CaCC activation in our experimental setup. Acute application of TG to EYFP-QL-transfected DRG neurons produced Ca2+ transients and some EYFP-QL quenching (fig. S3C, D).

To further probe the relationship between TRPV1 activation, ER Ca2+ release and ANO1 activation, we expanded our imaging approach to enable simultaneous but separate monitoring of Ca2+ levels in the ER and cytosol together with EYFP-QL quenching. To allow ER Ca2+ monitoring, we used the ER-targeted, Ca2+ sensing protein red-CEPIA (40). CEPIA fluorescence is reduced as Ca2+ is released from the ER. We transfected DRG cultures with both EYFP-QL and red-CEPIA and also loaded cells with fura-2AM, thereby allowing us to concurrently monitor CaCC activity, ER Ca2+ levels and cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics, respectively. A quadruple-wavelength (340/380/488/560nm) imaging protocol was utilized to simultaneously image all fluorophores in the experiments. Application of capsaicin produced Ca2+ transients and evoked significant EYFP-QL quenching but also resulted in a reduction in red-CEPIA fluorescence which indicates Ca2+ moving out of the ER after TRPV1 activation (Fig. 3E, F). This experiment also directly demonstrated good temporal correlation between ER Ca2+depletion, cytosolic Ca2+ elevation, and CaCC activation.

To validate our imaging results, we made whole-cell patch clamp recordings from cultured DRG neurons using physiological bath and internal pipette solutions. Application of capsaicin elicited robust inward currents (Fig. 4A). The current amplitude and kinetics of the response varied substantially; therefore, we quantified the area under the curve (A.U.C.) as a readout of TRPV1 activation. To test the contribution of ANO1 to this current, DRG neurons were preincubated with Ani9 (500 nM; Fig. 4A). In the presence of Ani9, the capsaicin-induced A.U.C. was significantly reduced, which was consistent with a previous study (10). To test if Ca2+ release from the ER was necessary for TRPV1-coupled ANO1 activation in DRG neurons, we pretreated neurons with TG (1 μM), which significantly reduced the capsaicin-induced A.U.C. (Fig. 4B, C). In the presence of TG, the majority of responses to capsaicin were lower compared to those evoked in control conditions (Fig. 4B, black trace; Fig. 4C). However, in 5 TG-treated neurons, capsaicin-induced responses were within the range of the average capsaicin response under control conditions. (Fig 4B, red trace; Fig. 4C). These results suggested three conclusions. First, ANO1-mediated Cl− current contributed substantially to the macroscopic currents induced in DRG neurons by capsaicin. Second, TRPV1-induced release of Ca2+ from the ER contributed substantially to TRPV1-coupled ANO1 activation in the majority of DRG neurons. Third, in some neurons, TRPV1-mediated Ca2+ influx was sufficient to induce strong ANO1 activation. The latter observation also argues against the possibility that TG directly interferes with TRPV1 function.

Figure 4. Thapsigargin disrupts capsaicin-induced currents in small-diameter DRG neurons.

(A) Representative whole-cell patch clamp recordings from DRG neurons held at −60mV during application of capsaicin (1 μM) in the absence (black trace) or presence (red trace) of the ANO1 inhibitor Ani9 (500 nM). (B) Responses to capsaicin (1 μM) in the presence of thapsigargin (TG; 1 μM). Capsaicin-induced currents that were smaller (black trace) or of comparable amplitude (red trace) to those obtained under control conditions are shown. (C) Scatter plots summarizing areas under the curve for capsaicin responses in experiments similar to these shown in (A, B); control (n=18 neurons), Ani9 (n=11 neurons); TG (n=16 neurons). In C, asterisks denote the following: *p<0.05; n.s, not significant (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with Mann-Whitney test).

TRPV1-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER requires crosstalk between plasmalemmal TRPV1 and PLC

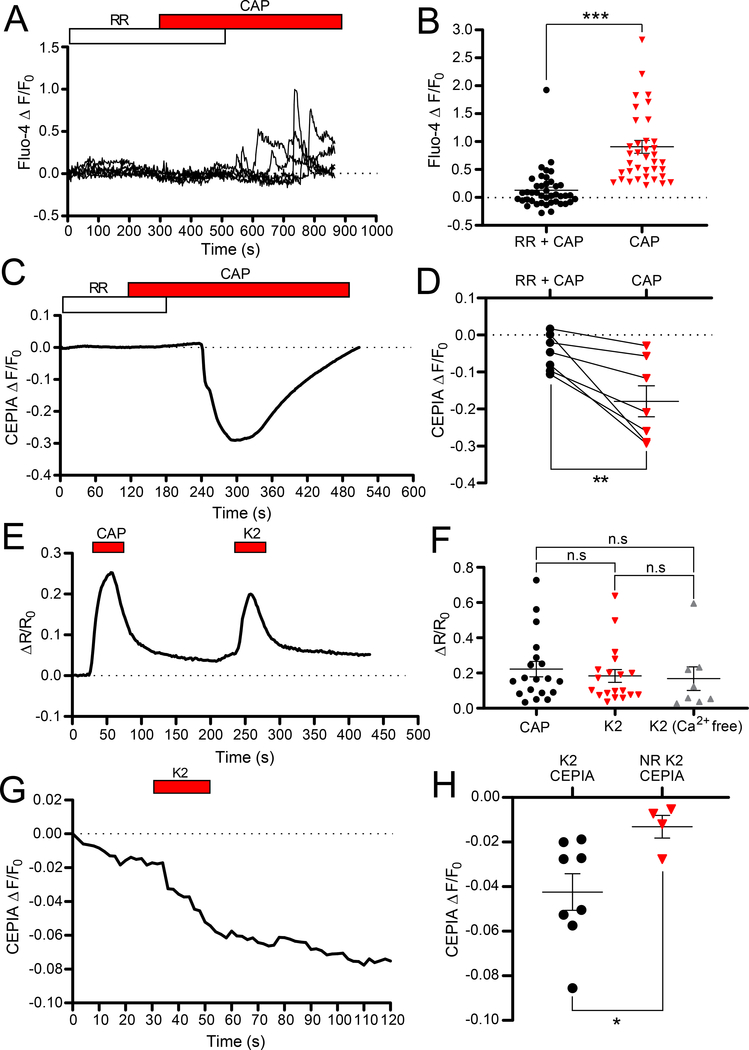

One important question that needed to be addressed was the manner in which capsaicin activated ER Ca2+ release. The two most likely scenarios suggested in the literature are activation of PLCs that cleave phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to produce IP3, which in turn, induces Ca2+ release through IP3Rs in the ER (41), and direct activation of ER-localized TRPV1 channels by capsaicin (42). To differentiate between the above mechanisms, we used two approaches. First, we performed fluo-4- Ca2+ imaging in DRG neurons treated with capsaicin after preincubation with (and in the presence of) ruthenium red (RR; 10 μM), a cell-impermeable TRPV1 blocker (Fig. 5A, B). Without access to the cytosol, RR should not inhibit putative ER-localized TRPV1 channels; therefore, capsaicin responses in the presence of this TRPV1 blocker could be attributed to this subset of channels (or any other intracellular TRPV1 channel pool). There was generally no response to capsaicin in the presence of RR (Fig. 5A, B). Upon wash out of RR and with capsaicin still present, Ca2+ responses were routinely recorded, suggesting that capsaicin did not induce noticeable Ca2+ transients through putative ER-resident TRPV1 channels in the majority of DRG neurons under our experimental conditions. Of 38 neurons that responded to capsaicin upon RR washout, only 4 cells produced discernable Ca2+ transients in the presence of RR and capsaicin. To specifically probe ER-Ca2+ release by TRPV1 activation, we performed imaging in DRG neurons expressing green-CEPIA to enable direct monitoring of ER Ca2+ levels. Capsaicin application produced significant ER-depletion only after RR washout (Fig. 5C, D).

Figure 5. ER-localized TRPV1 channels are not engaged during extracellular TRPV1 stimulation in small-diameter DRG neurons.

(A) Representative traces showing Ca2+ responses in small-diameter DRG neurons loaded with fluo-4AM in response to capsaicin (1 μM) in the presence of ruthenium red (RR; 10 μM) and after the RR washout. (B) Scatter plots summarizing experiments similar to those shown in (A); RR + CAP (n=42 neurons); CAP (n=38 neurons). (C) Representative trace showing fluorescence changes in a small-diameter DRG neurons transfected with green-CEPIA in response to capsaicin (1 μM) in the presence of RR (10 μM) and after the RR washout. (D) Scatter plots summarizing experiments similar to those shown in (C); n=6 neurons. (E) Representative traces showing a Ca2+ response in a small-diameter DRG neuron loaded with fura-2AM in response to capsaicin (1 μM) and K2 (30 μM). (F) Scatter plots summarizing experiments similar to those shown in (E); CAP n=19 neurons; K2 n=19 neurons; K2 (Ca2+ free) n=8 neurons. (G) Representative trace showing fluorescence changes in a small-diameter DRG neuron transfected with red-CEPIA in response to K2 (30 μM). (H) Scatter plots summarizing experiments similar to those shown in (F); K2 CEPIA n=8 neurons; NR K2 CEPIA n=4 neurons. In B, D, F, asterisks denote the following: *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001; n.s, not significant (B: Mann-Whitney test; D: paired t-test; F: Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with Mann-Whitney test; H: unpaired t-test).

Second, we utilized a cell-impermeable TRPV1 ligand to specifically activate PM-resident TRPV1 channels while avoiding activation of intracellular TRPV1s. Double-knot toxin (DkTx) is a vanillotoxin from the Chinese bird spider (Ornithoctonus huwena) which activates TRPV1 by binding to its extracellular outer pore turret (43–45). Here we used a single-knot derivative of DkTx, K2, which activates TRPV1 with improved efficacy (46). Both capsaicin and K2 (30 μM) evoked comparable Ca2+ transients in DRG neurons (Fig. 5E, F). In the absence of Ca2+, K2 still induced cytosolic Ca2+ transients (Fig. 5F and fig. S4). Finally, DRG cultures were transfected with red-CEPIA and K2 was applied to test whether Ca2+ release from the ER could be detected. K2 induced significant reduction in CEPIA fluorescence in 8/12 neurons tested (Fig. 5G, H). The data obtained with both a cell-impermeable TRPV1 agonist and a cell-impermeable antagonist suggested that activation of PM-localized TRPV1 channels was indeed capable of inducing Ca2+ release from the ER. Contribution of putative ER-localized TRPV1 channels to the capsaicin-induced cytosolic Ca2+ signal in DRG neurons appeared to be negligible.

The alternative possibility is that TRPV1 activation in DRG neurons was coupled to PLC activation and subsequent Ca2+ mobilization (31). To test this possibility, we transfected DRG neurons with an optical PIP2 reporter, GFP-tagged plextrin homology domain of PLCδ (PLCδ-PH-GFP) and monitored its translocation from the membrane to cytosol following the capsaicin application as a measure of PIP2 hydrolysis by PLC (47). Application of capsaicin (1 μM) induced translocation of PLCδ-PH-GFP from the PM to the cytosol (fig. S5A, B). Translocation was recorded even in the in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, albeit to a smaller extent (fig. S5B). Both of these findings are consistent with the previous report (31) and with our K2 experiments.

ANO1, TRPV1 and IP3R cluster at ER-PM junctions

Our results above suggested that there were functional interactions between ANO1, TRPV1 and IP3Rs that allowed TRPV1 to activate ANO1 through IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release, supplementing the relatively small Ca2+ influx through TRPV1 itself (30). For this mechanism to occur, there must be close proximity between these channel proteins. Previous work suggests that at least some ANO1 channels in DRG neurons reside at ER-PM junctions (1, 19), which are sites for intracellular information transfer where two membrane types come into very close juxtaposition (~15 nM) (48). At these sites ANO1 channels may physically interact with the IP3Rs (19, 49). To test if all three proteins were found in close association, we first utilized a proximity ligation assay (PLA) which detects two proteins that are closer than 30–40 nm from each other by manifesting characteristic 0.5–1 μm fluorescent puncta (50, 51). All antibodies used for PLA have been previously validated extensively by us in sensory neurons (19, 52).

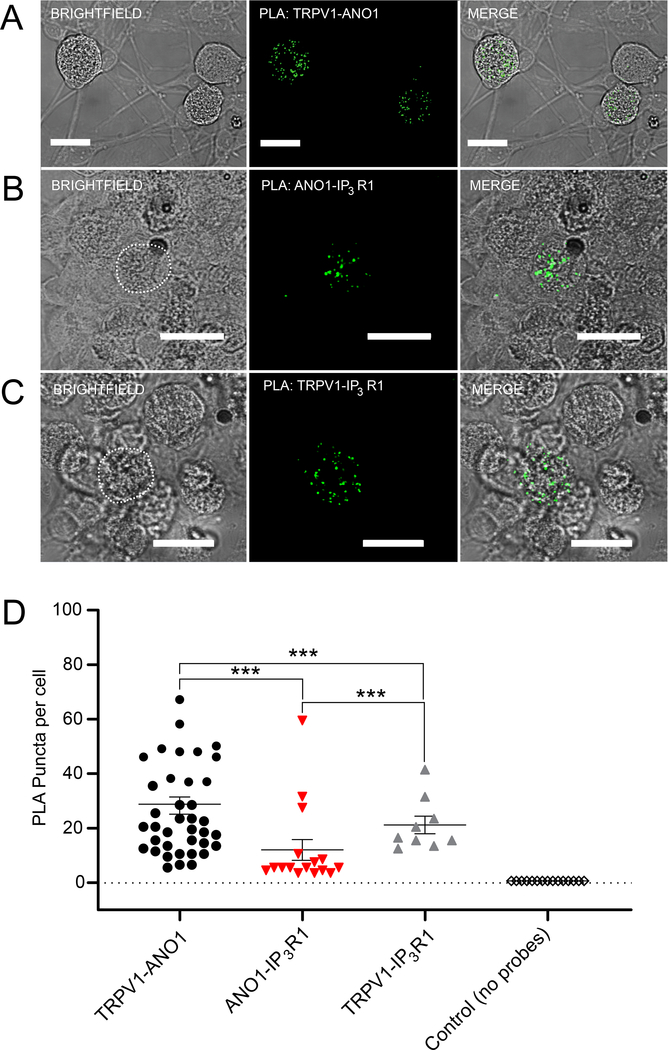

Specific PLA signals indicating close proximity were detected for TRPV1-ANO1 (Fig. 6A), ANO1-IP3R1 (Fig. 6B) and TRPV1-IP3R1 (Fig. 6C) protein pairs. A particularly high concentration of puncta per neuron was observed for the TRPV1-ANO1 pair (Fig. 6D). Positive PLA controls using two primary ANO1 antibodies raised in rabbit and goat and corresponding secondary PLA probes displayed robust puncta (fig. S6A). When only the rabbit primary antibody was used with both secondary probes, no signal was detected (fig. S6B). No puncta were observed when PLA was performed between IP3R1 and CD71 (also known as the transferrin receptor) (fig. S7A), a non-raft plasmalemmal protein (19, 53) that is not expected to co-localize with the members of the ANO1 junctional complex (19). These controls confirm PLA specificity in our experimental settings. Together, these data established that ANO1, TRPV1 and IP3R1 in DRG neurons often are found in close proximity. Of the three pairs tested, TRPV1-ANO1 complexes were more easily detectable, perhaps reflecting the PM residence of these proteins, whereas ANO1-IP3R1 and TRPV1-IP3R1 interactions exist across the ER-PM junction.

Figure 6. ANO1, TRPV1 and IP3R1s are in close proximity in small-diameter DRG neurons as tested with Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA).

(A-C) PLA images for TRPV1-ANO1 (A), ANO1-IP3R1 (B) and TRPV1-IP3R1 (C) pairs in DRG cultures. Left panels: brightfield images; middle panels: PLA puncta detection; right panels: merged images of brightfield and PLA puncta. Scale bars represent 20 μm. (D) Scatter plots summarizing number of PLA puncta per cell in experiments similar to these shown in (A-C); TRPV1-ANO1 (n=41 neurons), ANO1-IP3R1 (n=16 neurons); TRPV1-IP3R1 (n=16 neurons); black outlined symbols depict negative control where only one primary antibody (against ANO1) was used in conjunction with both PLA secondary probes (fig. S6A, B). In D, asterisks denote the following: ***p<0.001 (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with Mann-Whitney test).

STORM super-resolution microscopy allows direct visualization of individual ANO1-TRPV1-IP3R complexes

To further probe the existence of multi-channel complexes suggested by the above data with greater precision, we employed multi-wavelength super-resolution microscopy that can detect individual protein molecules in the membrane of fixed primary cells. Stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) (54, 55) allows multiple fluorophore excitation and detection using visible light, enabling localization of individual proteins, or complexes within a lateral resolution of less than 50 nm (52). Our previous work (52) describes in detail the extensive controls performed for such multi-wavelength STORM and the analysis paradigms that we have developed. The traditional STORM approach incorporates different “activator” fluorescent dyes (in this work we used Alexa Fluor 405, Cy2, and Cy3, excited at either 405 nm, 488 nm or 561 nm, respectively) that excite a common “reporter” fluorescent dye (for example, Alexa Fluor 647), that are both conjugated to secondary antibodies to identify which activator dye is the source of the excitation signal through tight temporal correlation. Each protein of interest is first labeled with appropriate primary antibodies that we have validated previously (19, 52). Because each secondary antibody is specific to the species of a corresponding primary antibody (mouse, rabbit, goat), we can simultaneously visualize individual complexes containing up to three different proteins. Control experiments by our group have shown a single tetrameric ion channel (such as voltage-gated K+ channel or a TRP channel) to be represented by a cluster of labeled “centroids” (single-molecule localizations) with a radius of ~30–50 nm, in which a single type of protein is represented by a cluster of densely proximal, like-colored centroids (52). Complexes containing two or three types of physically associated proteins are represented by clusters of centroids of two or three colors, with a slightly greater radial “footprint” of the antibody-dye label (52). Each standalone cluster of centroids of a single color represents a protein or a complex (such as a multimeric ion channel), recognized by a single type of a primary antibody. Clusters of centroids are objectively identified with a DBSCAN algorithm based on the original STORM localization data, which we previously described. Differential bleaching kinetics of Cy2 and Cy3 and Alexa Fluor 405 (fig. S8) was corrected.

First, we used STORM to probe for the same combinations of protein complexes tested in the PLA experiments (TRPV1-ANO1, ANO1-IP3R1 and TRPV1-IP3R1; Fig. 7A, B, C). Clusters of centroids representing individual ANO1, TRPV1 and IP3R1 channels were detected in each corresponding experiment and, as expected, a fraction of these centroid clusters were co-mingled within a combined radius of <120 nm, indicating close association. Even when in tight proximity (<100 nm), the footprint of each channel protein, as labeled by the STORM-visualized antibody/dyes could be individually resolved from the associated, coupled protein (Fig. 7A, B, C). Of the total detected clusters of centroids for TRPV1 and ANO1, 74.1 ± 6.5% were identified as co-localized channels based on our analysis paradigm (52) (Fig. 7D). The observed overlap of the two channels (as represented by their respective like-colored centroid clusters) in 2D space in the STORM image was usually not complete, suggesting discrete channels that were physically coupled in the PM within very close proximity. Non-colocalized ANO1 (2.3 ± 0.5%) and TRPV1 channels (23.5 ± 6.4%) were also detected which were a lower fraction compared to the co-localized population (table S1).

Figure 7. ANO1, TRPV1 and IP3R1s are found in close proximity in small-diameter DRG neurons as tested with STORM.

(A-C) Right panels display representative STORM images from DRG neurons, double-labeled for either TRPV1 and ANO1 (A), ANO1 and IP3R1 (B), or TRPV1 and IP3R1 (C) using dye-pairs of Alexa Fluor 405/ Alexa Fluor 647 (green centroids) and Cy3/ Alexa Fluor 647 (red centroids); scale is indicated by the white bars. Scale bars represent: Left panel, 5μm; middle panel, 1μm; right panel, 0.2μm for A-C. (D to F) Cluster distributions representing double-labeled TRPV1-ANO1; n=6 neurons (D), ANO1-IP3R1; n=9 neurons (E), or TRPV1-IP3R1; n=6 neurons (F). Summary data for cluster percentages, localization number per cluster, and probability distribution statistics are given in tables S1–S3.

In our experiments, STORM was performed on a microscope platform similar to that of total internal reflection microscopy (TIRF), in which illumination of cells is typically restricted to <400 nm from the surface of the glass, with the bulk of the light internally reflected (56, 57). In STORM, the angle of the laser light can be altered so that the illumination is not fully internally reflected, but adjusted so it is sufficiently oblique to penetrate up to ~1 μm, allowing illumination of the cytosol or organelles (such as the ER membrane) within 1 μm of the plasma membrane. Thus, we used STORM to examine the presence of complexes containing individual TRPV1 or ANO1 channels in the PM, and closely proximal to ER-resident IP3Rs. In double-labeling of ANO1 and IP3R1 under STORM, we detected co-localized ANO1-IP3R1 complexes, represented by clusters of centroids of two colors, accounting for 54.2 ± 4.3% of all detected centroid clusters observed in DRGs (Fig. 7E). Clusters of centroids of a single color, representing individual ANO1 channels or IP3R1s comprised 23.8 ± 4.0% and 22.0 ± 8.1% of all clusters, respectively. We also probed for complexes containing TRPV1 and IP3R1, and found co-localization of the two proteins, accounting for 51.8 ± 4.0% of detected clusters (Fig. 7F). Individual TRPV1 and IP3R1 clusters amounted to 34.0 ± 4.0% and 14.1 ± 0.8% of total clusters, respectively (table S1). As with the PLA data, the fraction of total TRPV1-ANO1 complexes per cell was more abundant as compared to complexes containing ANO1-IP3R1 or TRPV1-IP3R1. Although this cross-comparison of protein pairs (both by STORM and PLA) suggests the co-localization of ANO1, TRPV1 and IP3R1 that we can visualize, it does not provide quantitative evidence for the relative abundance of individual pairs, because the primary antibody affinities to their respective epitopes are not uniform and cannot be meaningfully normalized.

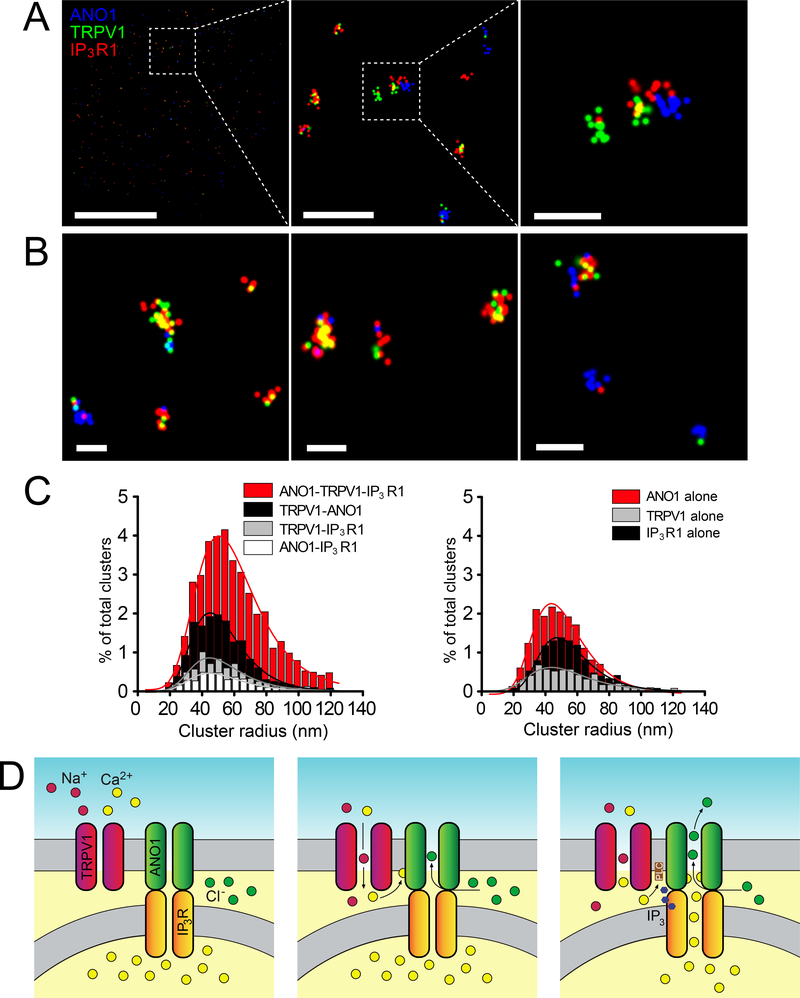

Because the PLA approach is limited to the detection of protein pairs only, we performed triple-labeled STORM imaging to probe for complexes containing all three proteins (ANO1, 405/647; TRPV1, 488/647; IP3R1, 561/647; Fig. 8A, B, C). The fraction of ANO1, TRPV1, and IP3R1 detected as co-localized together was 40.2 ± 0.2%, which accounted for the majority of the co-localizations compared to the pairs of only TRPV1-ANO1 (15.7 ± 1.6%), ANO1-IP3R1 (4.2 ± 0.04%), and TRPV1-IP3R1 (6.4 ± 1.6%) without a third protein observed (table S1). The ANO1-IP3R1-only and TRPV1-IP3R1-only populations were small and under the noise threshold of interactions detectable under STORM that we previously determined. This “noise threshold” was experimentally determined as ~10% of total clusters (based on spurious interactions of KCNQ2 and KCNQ4 channels) and in which the binned cluster radii are consistently less than 1% of the total fraction of clusters (52). Clustering between IP3R1 and CD71 amounted to 10.6 ± 1.6% of total clusters (fig. S7B), confirming the stringency of our threshold criteria and agreeing with the PLA results (fig. S7A).

Figure 8. Imaging of ANO1-TRPV1-IP3R1s complexes using three-color STORM.

(A, B) Representative STORM images for triple-labeled ANO1 (blue centroids) TRPV1 (green centroids) and IP3R1 (red centroids) in DRG neurons; scale is indicated by the white bars. Scale bars represent: A; Left panel, 5 μm; middle panel, 1 μm; right panel, 0.2 μm; B; 0.2 μm for all images. (C) Cluster distributions representing triple-labeled ANO1-TRPV1-IP3R1 combinations of proteins, protein pairs, or single proteins; n=12 neurons. Summary data for cluster percentages, localization number per cluster, and probability distribution statistics are given in tables S1–3. (D) Schematic depicting possible ANO1-TRPV1-IP3R1 functional coupling in DRG neurons. Our data suggests that a sizable fraction of ANO1, TRPV1 and IP3R1s are in close proximity at the ER-PM junctions and form complexes in small-diameter DRG neurons. TRPV1 activation leads to Na+ and Ca2+ influx (middle) but can also activate IP3R Ca2+ release (right), presumably through PLC activation. Release of Ca2+ from the ER maximizes ANO1 activation (right) which ultimately causes Cl− efflux and depolarization of the neuron.

In triple-labeled cells, TRPV1-ANO1 co-localizations remained prevalent, consistent with the large number of physical interactions of these two PM proteins in the double-label STORM experiments. However, the mean radius and centroid density of the ANO1-TRPV1-IP3R1 clusters were significantly larger than these of the TRPV1-ANO1 (no IP3R1) clusters, presumably due to the addition of the IP3R1s (tables S2 and S3). This is important when comparing these data to the double-labeled STORM experiments, in which the cluster populations of co-localized pairs of proteins were similar in size and centroid density (tables S2 and S3). Based on the proportion of complexes, we can surmise that ANO1 and TRPV1 are more likely to cluster in the presence of co-localized IP3R1, as evident in the significantly greater number of triple-color clusters including IP3R1s.

Discussion

In this work, we investigated the mechanism coupling TRPV1 channel opening with the activation of ANO1/CaCC in small-diameter (presumed nociceptive) DRG neurons. In the original report of TRPV1-ANO1 interactions, Takayama and colleagues put forward the most straightforward explanation for the mechanism of coupling: Opening of the TRPV1 channel pore delivers a sufficient amount of Ca2+ to directly activate co-localized ANO1 channels (10). Yet, several considerations compelled us to look beyond Occam’s razor. First, the affinity of Ca2+ ions for ANO1 at negative voltages is low (2–5 μM (7, 13)). Second, the Ca2+ current fraction amounts to no more than 10% of the macroscopic TRPV1 current under physiological conditions (30). This means that at similar whole-cell current amplitudes (at typical voltages during stimulation), the TRPV1-mediated Ca2+ influx would only deliver a fraction of Ca2+ ions to the cytosol as compared to those through VGCCs; however, even the latter source alone is not sufficient to produce strong ANO1 activation in DRG neurons ((19); present study). Third, evidence exists suggesting that the ER store refilling Ca2+ release activated channels (CRAC) in Xenopus oocytes are indirectly coupled to ANO1 activation. Ca2+ entering the cytosol through CRAC is not sufficient to activate ANO1 due to lack of close proximity between the ANO1 and CRAC. Instead, this cytosolic Ca2+ is first pumped into the ER by the SERCA pump and then released through the IP3Rs onto the juxtaposed ANO1 channels to produce activation of the latter (58). Finally, TRPV1 activates Ca2+-sensitive PLCδ and induces subsequent Ca2+ release from the ER through IP3Rs in DRG neurons and expression systems (31, 59). Thus, there might be both the need and a mechanism for more focused delivery of Ca2+ to ANO1 channels to ensure robust TRPV1-ANO1 coupling.

Here, using various approaches, we investigated the mechanism of localized Ca2+ signals linking ANO1 channel activation to TRPV1 in DRG neurons. First, we confirmed previous observations regarding the coupling of ANO1 to Ca2+ sources in DRG neurons: ANO1 can be reliably activated by GqPCR-induced Ca2+ release from the ER (Fig. 2, A, D, E and (7, 19, 49)) and by Ca2+ transients downstream of TRPV1 activation (Fig. 3A–F and (10)), whereas Ca2+ influx through VGCCs is poorly coupled to ANO1 activation (fig. S1A–B and (19)).

We also discovered that the predominant source of Ca2+ for TRPV1-coupled ANO1 activation is, as in the case with GqPCRs, release of Ca2+ from the ER. Indeed, ER store depletion significantly reduced capsaicin-induced Ca2+ transients (Fig. 3D) and CaCC activation (Fig. 4B and fig. S2B–C). In support of the conclusion that TRPV1 is capable of inducing robust Ca2+ release from the ER, we demonstrated that capsaicin-induced depletion of ER Ca2+was temporally correlated with the rise in cytosolic Ca2+ levels and CaCC activation in DRG neurons (Fig. 3E–F). Capsaicin still produced small Ca2+ transients in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 3D, fig. S2A), which could be explained by the presence of some functional TRPV1 channels within the ER membrane (60). Such a mechanism could also contribute to coupling of ER Ca2+ release to ANO1 activation. However, employing a cell membrane impermeable manipulators of TRPV1 activity, we showed that inhibition of PM-resident TRPV1 channels prevented capsaicin from producing cytosolic Ca2+ transients and ER store depletion (Fig. 5A–D). Moreover, activation of PM-resident TRPV1 channels produced Ca2+ transients even in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ and also induced ER store depletion (Fig. 5E–H, fig. S4). Hence, PM resident TRPV1 channels must be coupled to ER Ca2+ stores through intracellular signaling mechanisms. To probe this, we demonstrated that TRPV1 activation induced acute PIP2 hydrolysis, more robustly in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ but also in extracellular Ca2+-free conditions (fig. S5A, B). These observations agree with a previous study (31). The most straightforward mechanism for TRPV1-induced ER store release is stimulation of Ca2+-dependent PLCδ postulated earlier (31, 59). Some degree of capsaicin-induced ER store depletion observed in extracellular Ca2+-free conditions is intriguing as it points towards the existence of additional, hitherto unknown mechanism of coupling, perhaps involving other PLC isoforms. Identifying this mechanism will require further investigation. Yet, under physiological conditions, the Ca2+-dependent PLCδ mechanism of IP3 generation triggered by the Ca2+ influx through the TRPV1 channels is likely to be the dominant one.

Our PLA and STORM experiments revealed that a significant fraction of ANO1, TRPV1 and IP3R channels assemble into complexes containing two of the three, or all three together, with those containing IP3Rs located at ER-PM junctional nanodomains. At such junctions, B2Rs, ANO1 (1, 19, 61, 62) and TRPV1 channels (63) are likely anchored within caveolin-1-rich lipid rafts at the PM side of the junction, whereas IP3Rs at the ER are juxtaposed to ANO1. Using triple-label STORM, we identified the populations of each protein complex containing a combination of ANO1, TRPV1 and IP3Rs (Fig. 8, A to C). Our imaging conditions provided the ability to examine ER-localized IP3Rs that are proximal to the PM, but we also observed a small percentage of labeled IP3R1s (11%) that were not co-localized with ANO1 or TRPV1 channels. Based on the proximity analysis of ANO1 and TRPV1 co-localizations, there was a significantly greater likelihood that these channels are also in nanodomain clusters with IP3R1s, compared to TRPV1-ANO1 clusters without close proximity to IP3R1. However, not all TRPV1-ANO1 complexes were found being associated with IP3Rs; this may indicate a separate, direct coupling between TRPV1 and ANO1. Thus, we conclude, based on our functional data, that it is likely that not all ANO1 channels are activated solely through IP3R-dependent Ca2+ signaling (see below). The ANO1-IP3R1 and TRPV1-IP3R1 clusters were fewer in quantity overall (which was also consistent with the PLA data), suggesting that physical interaction with IP3Rs involves both ANO1 and TRPV1 association; this is also supported by the significant reduction in TRPV1-ANO1 coupling after ER Ca2+ store depletion. Similar signalling nanodomains may exist in other neuron types, and close association of B2Rs at the PM and IP3Rs at the ER membrane has been reported in sympathetic neurons (64, 65). Here we propose that a close-proximity arrangement of ANO1, TRPV1 and IP3R in DRG neurons ensures that Ca2+ influx through TRPV1 provides sufficiently high local [Ca2+] to activate PLCδ, thus ultimately stimulating juxtaposed IP3Rs that are in direct contact with ANO1 (19, 49); present study; Fig. 8D).

As mentioned, our data do not exclude direct coupling between TRPV1 and ANO1, whereby Ca2+ influx through the former directly gates the latter (Fig. 8D, middle panel). Indeed, some neurons in our assays still produced Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in response to capsaicin under conditions of ER Ca2+ depletion (fig. S2C and Fig. 4B, C). STORM data suggest that although the majority of multi-channel complexes are composed of all 3 proteins, there is still a sub-population of complexes consisting of only ANO1 and TRPV1, which may mediate such responses independently of IP3R activation or which may serve as ‘specialized’ heat sensors, which may only respond to noxious heat. Nevertheless, in the majority of neurons, ER Ca2+ release provides at least 50% or more of the Ca2+ ions necessary for the full activation of ANO1 by capsaicin-induced TRPV1 activation. This finding and the predominance of ANO1-TRPV1-IP3R1 complexes over TRPV1-ANO1 complexes (Fig. 8C) collectively suggests that IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release is indeed a critical factor for TRPV1-ANO1 coupling in sensory neurons.

One cannot exclude existence of more intricate mechanisms, such as what was previously suggested for the CRAC-ANO1 interplay (58). For instance, Ca2+ entering the cytosol through TRPV1 could be taken into the ER by the SERCA pump and then re-released onto the ANO1 channels. The necessity of CRAC to refill the ER stores suggests another intriguing question: whether the association of the multi-channel junctional complex reported here is static or being induced (or modified) in response to GqPCR activation. Indeed, Orai1 and STIM1 proteins form de novo junctional complexes to assemble into CRAC channels in response to the GqPCR-induced store depletion (66). Could individual components of ANO1-containing signaling complexes assemble in a similar way upon stimulation? Further research is needed to investigate the dynamics of ANO1-TRPV1-IP3R1 complex and its possible relationships with CRAC induction mechanisms.

The coupling between the TRPV1 and ANO1 channels in sensory neurons may hold a key to understanding thermal hypersensitivity (hyperalgesia) often produced by local inflammation. Indeed, a functional and/or physical interaction between TRPV1 and ANO1 channels in nociceptors might enable ANO1 to act as an ‘amplifier’ of TRPV1-mediated excitation, similar to the role of ANO2-mediated Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in olfactory neurons (67, 68). The contribution of ANO1 activation, which in sensory neurons is excitatory, could then increase the dynamic range of the electrochemical response to noxious heat or inflammation by nociceptors and this coupling may become more important in chronic pain, because the upregulation of both TRPV1 and ANO1 expression in several pain models have been reported (26, 69). It is also important to mention that ANO1 is a downstream component of various inflammatory mediator signaling cascades, which makes it an important player in inflammatory or chronic pain syndromes. The assembly of ANO1 into ‘junctional’ nanodomains in pain-sensing neurons could also explain how Ca2+ signals induced by the relevant stimuli, such as inflammatory mediators or heat, can cause ANO1-mediated excitation, whereas ‘irrelevant’ Ca2+ signals (such as those generated by VGCC during action potential firing) are precluded from having such an effect. Thus, the discovered mechanism exemplifies intricate wiring of intracellular Ca2+ signals in neurons providing for a high level of specificity and fidelity of intracellular signaling.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and transfection

DRGs were extracted from 7 day old Wistar rats and neurons were dissociated as previously described (8, 19). Cultures were maintained on 10 mm glass coverslips pre-coated with poly-D-lysine and laminin and cells were left to grow for 48 hours in DMEM supplemented with GlutaMAX I (Invitrogen), 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (50 U/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml) in a humidified incubator (5% CO2, 37°C). For transfection with the EYFP-QL or CEPIA constructs, the Lonza Nucleofector I was used and transfection was done before plating out the cells as described (70).

Live imaging

DRG cultures were loaded with 2 μM fura-2AM (Life Technologies) in the presence of 0.01% pluronic F-127 (Sigma) at 37°C for 45 minutes. Imaging was done using a Nikon TE-2000 microscope (inverted) with a 40× objective and the imaging setup consisted of a Polychrome V monochromator, IMAGO CCD camera and TILLVision 4.5.56 (TillPhotonics) or Live Acquisition 2.2.0 (FEI) software packages. For standard fura-2 imaging (no EYFP-QL transfection), excitation at 340 and 380nm was performed. For fluo-4 imaging, untransfected cells were loaded with fluo-4AM using the same method as for fura-2AM loading. An imaging system comprising of a Nikon TE-2000 E microscope with a DQC-FS camera and a Livescan™ Swept-field confocal system, was utilized for fluo-4 imaging. Analysis was done using Nikon Elements software.

To simultaneously image Ca2+ and I−, DRG neurons (~20 μm diameter) successfully transfected with EYFP-QL and loaded with fura-2 were selected for imaging; glial cells (identified by bipolar processes) were excluded from the analyses. The simultaneous Ca2+/I− imaging was performed using the UV-2A filter cube (Nikon) and excitation was performed at 340/380 (fura-2) and 488nm (EYFP-QL) wavelengths. Exposure time (typically within 50–200ms for fura-2 and 400–500ms for EYFP-QL) was set for each wavelength on a cell to cell basis, depending on the basal fluorescence intensity. For quadruple wavelength imaging, DRG (transfected with EYFP-QL) loaded with fura-2 were imaged using 340, 380, 488 and 560nm wavelength light using a custom-made dichroic/filter combination DC/59022bs-XR-360-UF1 and DC/59022m; Chroma).

Standard extracellular bath solution consisted of (mM): NaCl (160); KCl (2.5); MgCl2 (1); CaCl2 (2); HEPES (10) and Glucose (10); pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH (All from Sigma). I− containing solutions were produced by equimolar substitution of the NaCl with NaI (30 mM, 10 mM or 5mM). Compounds were added to the NaI containing solution whilst imaging: GABA, 100 μM (Tocris); capsaicin, 1 μM (Sigma); bradykinin, 250 nM (Merck), ruthenium red, 10 μM (Sigma). K2 was a generous gift from Dr. Avi Priel (The Institute for Drug Research, School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem). The depolarizing 50 mM K+ solution was produced by equimolar substitution of NaCl with KCl. Ca2+-free solutions were produced with increased NaCl (165 mM) to compensate for Cl− lost with the removal of CaCl2; 1 mM EGTA was also added. Pre-incubation with thapsigargin (1 μM; LKT Laboratories) or cyclopiazonic acid (1 μM; Tocris) was done during the fura-2 loading process where required and the compound was also kept in solutions throughout imaging. Gravity bath perfusion was used for all experiments apart from those involving K2, for which an Automate Scientific SmartSquirt Microperfusion system was utilized. A fine 100μm tip was used with this system and pressure was maintained at 3psi for all experiments using this perfusion method. The tip was positioned over DRG neurons selected for testing under 10× or 40× magnification before being activated.

Imaging data analysis

Analysis of primary data and statistics were performed in Microsoft Excel, Origin Pro and GraphPad Prism 8. Fura-2 ratios were normalized to R value at t=0 (R0) and expressed as a difference from R/R0 (ΔR/R0). EYFP-QL fluorescence intensity was normalized to fluorescence at t=0 (F0) and expressed as a difference from F0 (ΔF/F0), for each cell. Data from all cells were temporarily aligned to the point of R/R0 increase by 3 times the standard deviation of the baseline. Agonist-dependent EYFP-QL fluorescence quenching or red-CEPIA fluorescence intensity change were quantified from this point until the end of agonist application. Where possible, linear agonist-independent run-down of fluorescence signals was corrected before final analysis.

Electrophysiology

Whole cell voltage clamp recordings were performed as previously described (8). Patch electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass and fire polished to a final resistance of 2–4 MΩ. An EPC-10 patch clamp amplifier in combination with Patchmaster version 2×35 software (HEKA) was used. Standard extracellular bath solution consisted of (mM): NaCl (160); KCl (2.5); MgCl2 (1); CaCl2 (2); HEPES (10) and glucose (10); pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH (all from Sigma). The internal pipette solution consisted of (mM): CsCl (150); MgCl2 (5); K2ATP (1); NaGTP (0.1); EGTA (1) and HEPES (10). pH adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH (all from Sigma). After obtaining a gigaseal, whole cell configuration was attained and gap-free recordings performed at a holding voltage of −60mV. Capsaicin (1 μM) was applied to DRG neurons with or without 30 min pre-incubation with Ani9 (500 nM; Tocris) or thapsigargin (1 μM). Fitmaster v2×73.5 (HEKA) has been used for data analysis.

PLCδ-PH-GFP translocation

Cultured DRG neurons were transfected with the PLCδ-PH-GFP construct using the same method as for EYFP-QL and CEPIA transfection (see above). The Nikon confocal imaging and analysis system used for fluo-4AM live Ca2+ imaging was also used for PLCδ-PH-GFP translocation assays. GFP fluorescence intensity in the cytosolic regions of the cell was used as a measure of the probe translocation.

Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA)

PLA was performed using PLA kits (Sigma) as previously described (19). Antibodies used were ANO1 (1:200; Santa Cruz or 1:500; Abcam), TRPV1 (1:500; Neuromics) and IP3R1 (1:500; Calbiochem), CD71 (1:500, Santa Cruz). For anti-guinea pig antibodies (such as TRPV1), PLA ‘minus’ probes were manually conjugated onto an anti-guinea pig IgG antibody using a PLA conjugation kit. DRG cultures were prepared and plated on microscope slides (coated with poly-d-lysine and laminin) and permeabilized using acetone:methanol (1:1) on ice for 20 minutes and washed with PBS 3 times. Hydrophobic barriers were made on the slides using an ImmEdge hydrophobic barrier pen (Vector laboratories) to delimit reactions to ~1cm2 and blocking was done using the PLA blocking reagent for 30 minutes in a humidified incubator (37°C). Primary antibodies were then applied and left at 4°C overnight. The following day, PLA probes were applied to the samples; signals were amplified and detected according to the manufacturer’s instructions; and slides were sealed with DAPI-containing mounting medium (Sigma). Samples were imaged using the Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope. Green fluorescent puncta (0.5–1μm) were counted per cell using Zen imaging software (Zeiss).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M unless stated. Data were tested for normality and either parametric (Student’s t-test, ANOVA) or non-parametric (Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Mann Whitney test, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA) tests were carried out. Difference between means was considered significant at p<0.05. Approach to analysis of STORM data is described below.

Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy (STORM)

All images were acquired on a Nikon N-STORM super-resolution system (Nikon Instruments Inc.), consisting of a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope and an astigmatic 3D lens placed in front of the EMCCD camera to allow the Z coordinates to be most accurately determined. The laser set-up of our STORM system allows for the multiple, largely non-overlapping activator dyes, Alexa Fluor 405 carboxylic acid (Invitrogen, #A30000), Cy2 bisreactive dye pack (GE Healthcare, #PA22000), and Cy3 mono-reactive dye pack (GE Healthcare, #PA23001), to be conjugated to affinity-purified secondary antibodies from Jackson Immunoresearch, along with the reporter dye, Alexa Fluor 647 carboxylic acid (Invitrogen, #A20006) in order to acquire images from three different protein labels in the same experiment. Using the same primary antibodies used in the PLA experiments, we determined the extent of co-localization of TRPV1, ANO1, and IP3R1, as individual multi-protein complexes with either two or three photo-switchable dye activators, Alexa Fluor 405, Cy2, and Cy3, coupled to three distinct secondary antibodies (raised in different species) labeling the proteins in DRGs. The activator and reporter fluorophores were conjugated in-house to an appropriate unlabeled secondary antibody (71). STORM imaging was performed in a freshly prepared imaging buffer that contained (in mM): 50 Tris (pH 8.0), 10 NaCl and 10% (w/v) glucose, with an oxygen-scavenging GLOX solution (0.5mg/ml glucose oxidase (Sigma-Aldrich), 40 μg/ml catalase (Sigma-Aldrich), and 10 mM cysteamine MEA (Sigma-Aldrich). MEA was prepared fresh as a 1 M stock solution in water, stored at 4°C and used within 1 month of preparation. Acquisitions were made from between 2–4 different experiments for labeling and imaging. Images were rendered as a 2D Gaussian fit of each localization. The diameter of each point is representative of the localization precision (larger diameter, less precise), as is intensity (more intense, more precise). Signal-noise thresholds were handled as peak height above the local background in the N-STORM software (Elements). A detected peak was set as the central pixel in a 5×5 pixel area, and the average intensity of the 4 corner pixels was subtracted from intensity of the central pixel. Using a 100× objective and 16×16μm pixel area of the iXon3 camera, this corresponds to a 0.8×0.8μm physical neighborhood.

Adjustment of STORM localizations for differential rates of dye bleaching

The STORM acquisitions were carried out for a minimum of 6,000 activator-reporter cycles and until at least one of three activator laser wavelengths no longer registered localizations. We observed that the Alexa Fluor 405-Alexa Fluor 647 dye pair persisted stably for more cycles than the Cy2-Alexa Fluor 647 or Cy3-Alexa Fluor 647 dye pairs, independent of the secondary antibody that was conjugated (fig. S8). Therefore, we concluded that the Cy2 and Cy3 dyes bleach out more rapidly than Alexa Fluor 405 after many repeated activation cycles. Such differential rates of photobleaching would cause us to over-estimate the number of complexes containing a protein labeled by Alexa Fluor 405, and possibly under-estimate those without. Hence, we corrected for this artifact to the best of our ability. To more adequately compare the STORM localizations in the triple-labeled conditions, we first determined a linear approximation of the differential exponential decay of localizations for each corresponding activator dye. The cumulative probability distributions demonstrated that Alexa Fluor 405 had a significantly greater number of localizations than equally labeled Cy2 or Cy3 at approximately 3,000 laser activation cycles (36,000 total frames) and beyond (fig. S8). The factor of decay was used to time-dependently correct for this by probabilistically excluding Alexa Fluor 405-specific localizations from the cluster detection analysis to compensate for this, preventing oversampling above that of Cy2 or Cy3 molecules. After this adjustment, the numbers of clusters of each combination of multi-channel complexes did not significantly change due to the details of our sampling paradigm, except for those of Alexa Fluor 405-only centroid clusters. We estimate that the applied compensation paradigm corrected for the above mentioned artifact by >90%.

Cluster size and localization proximity analysis

Unfiltered STORM localization data were exported as molecular list text files from Nikon-Elements and were analyzed with in-house software incorporating a density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) (72). A dense region or cluster was defined as localizations within a directly-reachable radius proximity (epsilon) from a criterion minimum number of other core localizations (MinPts). Density-reachable points were localizations that were within the epsilon radius of a single core point and thus considered part of the cluster. Localizations considered to be noise were points that were not within the epsilon distance of any core points of a cluster. We derived the appropriate epsilon parameter using the nearest-neighbor plot from single-dye labeled controls; cluster detection was determined for epsilon between 20 and 80nm, which were the nearest-neighbor localization distances representing 95% of area under the curve. DBSCAN parameters were verified by measuring goodness of fit to Gaussian distribution with cluster population data from single-dye labeled controls, and set for distance of directly reachable points at 50nm (epsilon) and 7 minimum points (MinPts). These parameters were found to be the most stringent possible, that also reliably fit the control data. For cluster detection, each localization was assessed based on its corrected X and corrected Y 2D spatial coordinates, and the associated activator dye was tracked throughout analysis. Detected clusters were tabulated by the composition of resident activator dyes contributing to the total neighborhood of localizations for that cluster. Clusters were categorized based on activator dye composition as Alexa Fluor 405 only, Cy2 only, Cy3 only, Alexa Fluor 405 + Cy2, Alexa Fluor 405 + Cy3, or Alexa Fluor 405 + Cy2 + Cy3, according to the dye conjugated to each antibody label. Cluster radius size (nm) data were placed in probability distribution histograms with bin size of 5nm. Based on the observation that a majority of cluster distributions displayed positive skew, distributions were fit by the generalized extreme value distribution function: f(x) = e−(x−1+ê−x). Cluster size values were reported as mean ± SEM. The β continuous scale parameter of each cluster distribution was derived from the mean value of the extreme distribution (Mean = μ + γβ, γ: 0.5772, Euler-Mascheroni constant) and was determined as a metric for “tailedness” of cluster size distribution. In addition, the percentage of clusters belonging to a labeling category out of total clusters was compared. Cumulative distribution functions of cluster categories were compared with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Population statistics for each cluster category were derived from 6–12 cells per staining and imaging condition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gabriel Hoppen (University of Leeds) for assistance with PLA controls and Dr. Avi Priel (The Institute for Drug Research, School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem) for the kind gift of the K2 toxin.

Funding: This work was supported by the BBSRC grants BB/R02104X/1 and BB/R003068/1 to N.G.; by the National Institutes of Health Grants R01 NS094461 and R01 NS043394 to M.S.S. by the Presidential Scholar award to M.S.S. and by a postdoctoral training fellowship to C.M.C. from Training Grant T32 HL007446 (James D. Stockand, PI).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

References and Notes

- 1.Jin X, Shah S, Du X, Zhang H, Gamper N, Activation of Ca2+-activated Cl− channel ANO1 by localized Ca2+ signals. J Physiol 594, 19–30 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartzell C, Putzier I, Arreola J, Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu Rev Physiol 67, 719–758 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pedemonte N, Galietta LJ, Structure and function of TMEM16 proteins (anoctamins). Physiol Rev 94, 419–459 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang F, Wong X, Jan LY, International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXV: calcium-activated chloride channels. Pharmacol Rev 64, 1–15 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E, Pfeffer U, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ, TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science 322, 590–594 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY, Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell 134, 1019–1029 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS, Park SP, Lee J, Lee B, Kim BM, Raouf R, Shin YK, Oh U, TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature 455, 1210–1215 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu B, Linley JE, Du X, Zhang X, Ooi L, Zhang H, Gamper N, The acute nociceptive signals induced by bradykinin in rat sensory neurons are mediated by inhibition of M-type K+ channels and activation of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J Clin Invest 120, 1240–1252 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho H, Yang YD, Lee J, Lee B, Kim T, Jang Y, Back SK, Na HS, Harfe BD, Wang F, Raouf R, Wood JN, Oh U, The calcium-activated chloride channel anoctamin 1 acts as a heat sensor in nociceptive neurons. Nat Neurosci 15, 1015–1021 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takayama Y, Uta D, Furue H, Tominaga M, Pain-enhancing mechanism through interaction between TRPV1 and anoctamin 1 in sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 5213–5218 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funk K, Woitecki A, Franjic-Wurtz C, Gensch T, Mohrlen F, Frings S, Modulation of chloride homeostasis by inflammatory mediators in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Mol Pain 4, 32 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pieraut S, Laurent-Matha V, Sar C, Hubert T, Mechaly I, Hilaire C, Mersel M, Delpire E, Valmier J, Scamps F, NKCC1 phosphorylation stimulates neurite growth of injured adult sensory neurons. J Neurosci 27, 6751–6759 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao Q, Yu K, Perez-Cornejo P, Cui Y, Arreola J, Hartzell HC, Voltage- and calcium-dependent gating of TMEM16A/Ano1 chloride channels are physically coupled by the first intracellular loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 8891–8896 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paulino C, Kalienkova V, Lam AKM, Neldner Y, Dutzler R, Activation mechanism of the calcium-activated chloride channel TMEM16A revealed by cryo-EM. Nature 552, 421–425 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Contreras-Vite JA, Cruz-Rangel S, De Jesus-Perez JJ, Figueroa IA, Rodriguez-Menchaca AA, Perez-Cornejo P, Hartzell HC, Arreola J, Revealing the activation pathway for TMEM16A chloride channels from macroscopic currents and kinetic models. Pflugers Arch 468, 1241–1257 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du X, Hao H, Gigout S, Huang D, Yang Y, Li L, Wang C, Sundt D, Jaffe DB, Zhang H, Gamper N, Control of somatic membrane potential in nociceptive neurons and its implications for peripheral nociceptive transmission. Pain 155, 2306–2322 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sapunar D, Ljubkovic M, Lirk P, McCallum JB, Hogan QH, Distinct membrane effects of spinal nerve ligation on injured and adjacent dorsal root ganglion neurons in rats. Anesthesiology 103, 360–376 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amir R, Liu CN, Kocsis JD, Devor M, Oscillatory mechanism in primary sensory neurones. Brain 125, 421–435 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin X, Shah S, Liu Y, Zhang H, Lees M, Fu Z, Lippiat JD, Beech DJ, Sivaprasadarao A, Baldwin SA, Zhang H, Gamper N, Activation of the Cl− Channel ANO1 by Localized Calcium Signals in Nociceptive Sensory Neurons Requires Coupling with the IP3 Receptor. Sci Signal 6, ra73 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward SM, Kenyon JL, The spatial relationship between Ca2+ channels and Ca2+-activated channels and the function of Ca2+-buffering in avian sensory neurons. Cell Calcium 28, 233–246 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bao R, Lifshitz LM, Tuft RA, Bellve K, Fogarty KE, ZhuGe R, A close association of RyRs with highly dense clusters of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels underlies the activation of STICs by Ca2+ sparks in mouse airway smooth muscle. J Gen Physiol 132, 145–160 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer PJ, The local Ca concentration profile in the vicinity of a Ca channel. Cell Biochem Biophys 35, 49–61 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizzuto R, Pozzan T, Microdomains of intracellular Ca2+: molecular determinants and functional consequences. Physiol Rev 86, 369–408 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linley JE, Rose K, Ooi L, Gamper N, Understanding inflammatory pain: ion channels contributing to acute and chronic nociception. Pflugers Arch 459, 657–669 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petho G, Reeh PW, Sensory and signaling mechanisms of bradykinin, eicosanoids, platelet-activating factor, and nitric oxide in peripheral nociceptors. Physiol Rev 92, 1699–1775 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee B, Cho H, Jung J, Yang YD, Yang DJ, Oh U, Anoctamin 1 contributes to inflammatory and nerve-injury induced hypersensitivity. Mol Pain 10, 5 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ru F, Sun H, Jurcakova D, Herbstsomer RA, Meixong J, Dong X, Undem BJ, Mechanisms of pruritogen-induced activation of itch nerves in isolated mouse skin. J Physiol, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunzelmann K, Cabrita I, Wanitchakool P, Ousingsawat J, Sirianant L, Benedetto R, Schreiber R, Modulating Ca2+ signals: a common theme for TMEM16, Ist2, and TMC. Pflugers Arch 468, 475–490 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai Y, Moriyama T, Higashi T, Togashi K, Kobayashi K, Yamanaka H, Tominaga M, Noguchi K, Proteinase-activated receptor 2-mediated potentiation of transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 activity reveals a mechanism for proteinase-induced inflammatory pain. J Neurosci 24, 4293–4299 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samways DS, Khakh BS, Egan TM, Tunable calcium current through TRPV1 receptor channels. J Biol Chem 283, 31274–31278 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lukacs V, Yudin Y, Hammond GR, Sharma E, Fukami K, Rohacs T, Distinctive changes in plasma membrane phosphoinositides underlie differential regulation of TRPV1 in nociceptive neurons. J Neurosci 33, 11451–11463 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galietta LJ, Haggie PM, Verkman AS, Green fluorescent protein-based halide indicators with improved chloride and iodide affinities. FEBS Lett 499, 220–224 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansson T, Norris T, Peilot-Sjogren H, Yellow fluorescent protein-based assay to measure GABA(A) channel activation and allosteric modulation in CHO-K1 cells. PLoS One 8, e59429 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Namkung W, Yao Z, Finkbeiner WE, Verkman AS, Small-molecule activators of TMEM16A, a calcium-activated chloride channel, stimulate epithelial chloride secretion and intestinal contraction. FASEB J 25, 4048–4062 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Du X, Hao H, Yang Y, Huang S, Wang C, Gigout S, Ramli R, Li X, Jaworska E, Edwards I, Deuchars J, Yanagawa Y, Qi J, Guan B, Jaffe DB, Zhang H, Gamper N, Local GABAergic signaling within sensory ganglia controls peripheral nociceptive transmission. J Clin Invest 127, 1741–1756 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson B, Characteristics of GABA-activated chloride channels in mammalian dorsal root ganglion neurones. J Physiol 411, 285–300 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallagher JP, Higashi H, Nishi S, Characterization and ionic basis of GABA-induced depolarizations recorded in vitro from cat primary afferent neurones. J Physiol 275, 263–282 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seo Y, Lee HK, Park J, Jeon DK, Jo S, Jo M, Namkung W, Ani9, A Novel Potent Small-Molecule ANO1 Inhibitor with Negligible Effect on ANO2. PLoS One 11, e0155771 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Premkumar LS, Ahern GP, Induction of vanilloid receptor channel activity by protein kinase C. Nature 408, 985–990 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki J, Kanemaru K, Ishii K, Ohkura M, Okubo Y, Iino M, Imaging intraorganellar Ca2+ at subcellular resolution using CEPIA. Nat Commun 5, 4153 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lukacs V, Thyagarajan B, Varnai P, Balla A, Balla T, Rohacs T, Dual regulation of TRPV1 by phosphoinositides. J Neurosci 27, 7070–7080 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas KC, Sabnis AS, Johansen ME, Lanza DL, Moos PJ, Yost GS, Reilly CA, Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 agonists cause endoplasmic reticulum stress and cell death in human lung cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321, 830–838 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bohlen CJ, Priel A, Zhou S, King D, Siemens J, Julius D, A bivalent tarantula toxin activates the capsaicin receptor, TRPV1, by targeting the outer pore domain. Cell 141, 834–845 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao E, Liao M, Cheng Y, Julius D, TRPV1 structures in distinct conformations reveal activation mechanisms. Nature 504, 113–118 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bae C, Anselmi C, Kalia J, Jara-Oseguera A, Schwieters CD, Krepkiy D, Won Lee C, Kim EH, Kim JI, Faraldo-Gomez JD, Swartz KJ, Structural insights into the mechanism of activation of the TRPV1 channel by a membrane-bound tarantula toxin. eLife 5, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geron M, Kumar R, Zhou W, Faraldo-Gomez JD, Vasquez V, Priel A, TRPV1 pore turret dictates distinct DkTx and capsaicin gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E11837–E11846 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gamper N, Rohacs T, Phosphoinositide sensitivity of ion channels, a functional perspective. Subcell Biochem 59, 289–333 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dickson EJ, Hille B, Understanding phosphoinositides: rare, dynamic, and essential membrane phospholipids. Biochem J 476, 1–23 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cabrita I, Benedetto R, Fonseca A, Wanitchakool P, Sirianant L, Skryabin BV, Schenk LK, Pavenstadt H, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K, Differential effects of anoctamins on intracellular calcium signals. FASEB J 31, 2123–2134 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weibrecht I, Leuchowius KJ, Clausson CM, Conze T, Jarvius M, Howell WM, Kamali-Moghaddam M, Soderberg O, Proximity ligation assays: a recent addition to the proteomics toolbox. Expert Rev Proteomics 7, 401–409 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soderberg O, Gullberg M, Jarvius M, Ridderstrale K, Leuchowius KJ, Jarvius J, Wester K, Hydbring P, Bahram F, Larsson LG, Landegren U, Direct observation of individual endogenous protein complexes in situ by proximity ligation. Nat Methods 3, 995–1000 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, Carver CM, Choveau FS, Shapiro MS, Clustering and Functional Coupling of Diverse Ion Channels and Signaling Proteins Revealed by Super-resolution STORM Microscopy in Neurons. Neuron 92, 461–478 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amsalem M, Poilbout C, Ferracci G, Delmas P, Padilla F, Membrane cholesterol depletion as a trigger of Nav1.9 channel-mediated inflammatory pain. EMBO J 37, pii: e97349 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dani A, Huang B, Bergan J, Dulac C, Zhuang X, Superresolution imaging of chemical synapses in the brain. Neuron 68, 843–856 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rust MJ, Bates M, Zhuang X, Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). Nat Methods 3, 793–795 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Axelrod D, Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy in cell biology. Methods Enzymol 361, 1–33 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bal M, Zaika O, Martin P, Shapiro MS, Calmodulin binding to M-type K+ channels assayed by TIRF/FRET in living cells. J Physiol 586, 2307–2320 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]