Review on viral chemokine homologues identified in Herpesviridae family, their implications in viral pathogenesis and leukocyte migration, and their potential clinical applications.

Keywords: viral chemokine, immune evasion, Chemotaxis, chemokine receptors

Abstract

Viruses use diverse strategies to elude the immune system, including copying and repurposing host cytokine and cytokine receptor genes. For herpesviruses, the chemokine system of chemotactic cytokines and receptors is a common source of copied genes. Here, we review the current state of knowledge about herpesvirus-encoded chemokines and discuss their possible roles in viral pathogenesis, as well as their clinical potential as novel anti-inflammatory agents or targets for new antiviral strategies.

Introduction

Herpesviruses form a family of large, enveloped dsDNA viruses that cause acute, chronic, persistent, and subclinical infections, while ultimately establishing a long-lived latent state in their hosts [1]. Humans are the sole natural host for 9 pathogenic HHVs (Table 1), whose prevalence rates may reach up to 95–100%, owing to high transmissibility, prolonged clinical and viral latency, and sophisticated immune-evasion capabilities. During the pre-PCR era, latency was described as a silent and almost inert viral state, but today, we know that herpesvirus latency, typically established as episomes in the infected cell nucleus, is a dynamic process in which the virus is continuously screening and challenging the host immune-system fitness, looking for reactivation opportunities [2]. Indeed, viral reactivation, in addition to acute infection, is an important cause of HHV-related disease. Although virion production and gene expression are largely restricted during latency, latent herpesviruses still produce viral proteins and microRNAs, with 2 major goals: to keep the infected cell alive and to evade the host immune system [3–5]. The importance of the immune response in herpesvirus infections is revealed, not only by the potentially life-threatening nature of acute or reactivated infection in immunocompromised hosts but also, by the large number of immunosubversive virulence genes that have been identified in HHV genomes [6]. Some of these genes are copies of host genes encoding immunoregulatory factors [7], repurposed by the virus through extensive mutation.

TABLE 1.

HHVs

| Formal name | Common name | Subfamily | Genus | Clinical features | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HHV-1 | HSV-1 | Alphaherpesvirinae | Simplexvirus | Oral and genital blisters | 67% worldwide [229] |

| HHV-2 | HSV-2 | Alphaherpesvirinae | Simplexvirus | Genital blisters | 11% worldwide [230] |

| HHV-3 | VZV | Alphaherpesvirinae | Varicellovirus | Varicella (chickenpox), herpes zoster (shingles) | >90% adults [231] |

| HHV-4 | EBV | Gammaherpesvirinae | Lymphocryptovirus | Infectious mononucleosis, B cell lymphomas, NK/T cell lymphoma, nasopharyngeal, and gastric carcinomas | 20–85% children |

| >90% adults [3, 232, 233] | |||||

| HHV-5 | HCMV | Betaherpesvirinae | CMV | Fetal disorders, transplant rejection, inflammatory diseases | 50–70% North America |

| >90% IBSAa countries | |||||

| 40–90% Europe [234] | |||||

| HHV-6A | – | Betaherpesvirinae | Roseolovirus | Exanthem subitum, neuroinflammatory diseases | 70–100% worldwide [235] |

| HHV-6B | – | Betaherpesvirinae | Roseolovirus | Exanthem subitum, neuroinflammatory diseases | 70–100% worldwide [235] |

| HHV-7 | – | Betaherpesvirinae | Roseolovirus | Exanthem subitum | >85% worldwide [126] |

| HHV-8 | KSHV | Gammaherpesvirinae | Rhadinovirus | KS, multicentric Castleman disease, primary effusion lymphoma, KICS | 50% sub-Saharan countries |

| 5–10% Western countries [155] |

Subfamily, genus, clinical features, and prevalence rates are indicated for each HHV. VZV is the only HHV with a licensed vaccine. VZV prevalence rates correspond to prevaccine studies.

aIBSA countries are India, Brazil, and South Africa.

Chemokines and chemokine receptors represent a high proportion of the relatively few human genes that have herpesvirus homologs. Why herpesviruses prefer them may relate to the strategic role they play in mediating leukocyte trafficking to sites of viral infection during the immune response. The human chemokine system includes ∼50 different protein ligands, 20 cellular receptors belonging to the GPCR superfamily, and 4 ACKRs [8]. Chemokines can be classified into 1 of 4 different subgroups—C, CC, CXC, or CX3C—depending on the number and spacing of conserved N-terminal cysteines. Some chemokine-specific GPCRs bind promiscuously to multiple different chemokines but always from the same structural subgroup. Unlike chemokine receptors, which are defined by function (chemokine binding and signal transduction), chemokines are defined by structure. Host chemokines were discovered and characterized first, which enabled rapid identification of viral chemokines by in silico sequence analysis of viral ORFs as their sequences came out. In contrast, the first viral ORFs encoding chemokine receptors were discovered before host chemokine receptors, including HCMV US28 in 1990 [9], a functional homolog of human CCR1 [10], and HVS ECRF3 in 1992 [11], a functional homolog of human CXCR2 [12] (Table 2). Characterization of these viral proteins as chemokine receptors followed shortly thereafter and was enabled by discovery and characterization of their host homologs. Since then, many herpesvirus chemokines have been identified, particularly in CMVs, roseoloviruses, and KSHV (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Herpesvirus-encoded chemokine receptors

| Virus | ORF | Ligands | Constitutive activity | Biologic effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCMV | US28 | CCL2–7, CCL11, CCL13, CCL26, CCL28, CX3CL1, vCCL2 | Yes | Oncogenesis, angiogenesis, viral dissemination, cellular migration, HIV coreceptor, inflammatory response, cell proliferation | [10, 172, 236–242] |

| HHV-6 | U12 | CCL2–5 | ND | Cellular migration | [138] |

| U51 | CCL2, CCL5, CCL7, CCL11, CCL13, CCL19, CCL22, XCL1, CX3CL1, vCCL2 | Yes | Viral replication, cellular migration, cell survival | [139, 140, 243, 244] | |

| HHV-7 | U12 | CCL17, CCL19, CCL21, CCL22 | ND | Cellular migration | [245–247] |

| U51 | CCL17, CCL19, CCL21, CCL22 | ND | Cellular migration | [245, 247] | |

| KSHV | ORF74a | CCL1, CCL5, CXCL1–8, CXCL10, CXCL12, vCCL2 | Yes | Oncogenesis, pathogenesis, angiogenesis, viral replication, cellular migration, cell proliferation, inflammatory response, cell survival | [177–179, 200, 248–252] |

| HVS | ORF74b | CXCL1, CXCL3, CXCL6–8, vCCL2 | Yes | Cellular migration, T cell activation | [12, 253, 254] |

| MHV-68 | ORF74 | CXCL1, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, CXCL8, CXCL10, Cxcl10 | No | Oncogenesis, viral replication and reactivation, cellular migration | [255–257] |

The corresponding encoding viruses [betaherpesviruses: HCMV, HHV-6, and HHV-7; and gammaherpesviruses: KSHV, HVS, and murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68)], ORFs, ligands (human chemokines, uppercase letters; mouse chemokines, lowercase letters), and the presence or absence of ligand-independent, constitutive activity (ND, not determined) for each viral chemokine receptor are indicated. The biologic processes proposed to be affected by the activity of each herpesvirus chemokine receptor are listed.

KSHV ORF74 is also known as vGPCR.

HVS ORF74 is also designated ECRF3.

TABLE 3.

Viral chemokines encoded by herpesviruses

| Group | Name | Virus | Gene | Effect | Receptor | Bioactivity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | |||||||

| vXCL1 | RCMV English | e156.5 | Agonist | Xcr1 | Recruitment of rat CD4− DCs | [109] | |

| UL130 | HCMV | UL130 | ND | ND | Full viral infectivity in monocytes and epithelial and endothelial cells | [46, 55, 56] | |

| gL | α-Herpesviruses | UL1 (HSV-1/2) | ND | ND | Viral cell entry | [55, 216, 217, 221] | |

| ORF60 (VZV) | |||||||

| CC | |||||||

| vCCL1 | KSHV | K6 | Agonist | CCR8 | Recruitment of Th2 cells and Treg, angiogenic, antiapoptotic | [163–166, 170] | |

| vCCL2 | KSHV | K4 | Agonist | CCR3, CCR8 | Recruitment of Th2 cells, angiogenic | [163, 169, 174] | |

| Antagonist | CCR1, CCR2, CCR5, CCR10, CXCR4, CX3CR1, XCR1 | Inhibition of NK and Th1 cell migration | [166, 172, 173, 175] | ||||

| vCCL3 | KSHV | K4.1 | Agonist | CCR4, XCR1 | Recruitment of Th2 cells and mouse CD8+ DCs | [166, 196] | |

| vCCL4a | HHV-6A | U83A | Agonist | CCR1, CCR4, CCR5, CCR6, CCR8 | Recruitment of Th2 and Th1 cells | [143] | |

| vCCL4b | HHV-6B | U83B | Agonist | CCR2 | Recruitment of monocytes | [115, 141] | |

| RCK-3 | RCMV Maastricht | r129 | Agonist | Ccr3, Ccr4, Ccr5, Ccr7 | Recruitment of primary rat macrophages and lymphocytes | [93] | |

| RCK-2 | RCMV Maastricht | r131 | ND | ND | Persistent infection in salivary glands | [91] | |

| MCK-2 | MCMV | m131/m129 | ND | ND | Full viral infectivity in macrophages, recruitment of monocytes, persistent infection in salivary glands | [76, 83, 85, 87] | |

| ECK-2 | RCMV English | e131/e129 | ND | ND | ND | [90] | |

| UL128 | HCMV | UL128 | ND | ND | Full viral infectivity in monocytes, epithelial and endothelial cells, recruitment of PBMCs, inhibition of monocyte chemotaxis | [36, 37, 46] | |

| gL | γ-Herpesviruses | BKRF2 (EBV) ORF47 (KSHV) | ND | ND | Viral cell entry | [220, 222] | |

| CXC | |||||||

| vCXCL1 | HCMV | UL146 | Agonist | CXCR1, CXCR2, CX3CR1 | Recruitment of neutrophils and NK cells | [94–96] | |

| vCXCL2 | HCMV | UL147 | ND | ND | ND | [32, 94, 101] |

Viral chemokines are grouped by structural group based on the cysteine residues in their N-terminal domain. The virus, coding gene, biochemical effect (agonist or antagonist), cellular receptors (human receptors, uppercase letters; nonhuman receptors, lowercase letters), and proposed bioactivities are indicated for each chemokine.

Viral chemokines and chemokine receptors, together with a group of structurally unique, soluble, chemokine-binding proteins, represent the 3 major molecular strategies that have been identified in herpesviruses for subversion and repurposing of the host chemokine network [13]. Examples of all 3 strategies have also been found in poxviruses [14], which comprise a family of large DNA viruses that cause acute cytolytic infections; however, to date, in the Poxviridae family, there is only 1 known viral chemokine—molluscum contagiosum virus MC148 [15]—and 1 viral chemokine receptor—yaba-like disease virus 7L, a signaling receptor for CCL1 [16]. Besides the herpesvirus-encoded chemokine receptors summarized in Table 2, the other vGPCRs identified in HHVs—HCMV US27, UL33 and UL78, and EBV BILF1—remain orphan [17, 18]. More information about viral chemokine receptors and vGPCRs can be found in excellent reviews of the field [19–21].

Previous reviews of herpesvirus chemokines have been restricted to brief summaries in general reviews of diverse viral immune-evasion strategies or in articles restricted to 1 particular herpesvirus genus. Our goal in the present review is to provide a comprehensive treatment focused on all known viral chemokines in the Herpesviridae family that addresses their potential roles in viral pathogenesis, as well as possible clinical applications. It is important to note that some viral chemokines do not have a demonstrated effect on cellular migration or a known cellular receptor yet (Table 3). However, the structural and sequence characteristics of these viral proteins define them as extended chemokine family members; hence, they are presented here alongside functional viral chemokines with proven effects on cellular chemotaxis (Table 3).

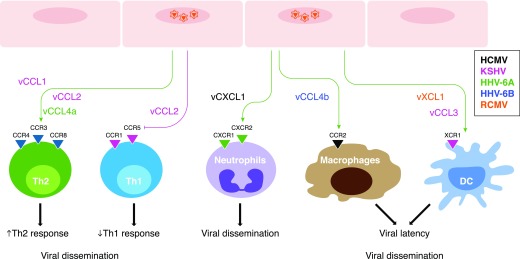

Herpesvirus chemokines may have diverse activities targeting multiple immune cell populations during different phases of infection but ultimately, with 2 major common goals: to facilitate viral dissemination and latency and to impair the host immune response. For this, there are examples of viral chemokines that may act as antagonists of host chemokine receptors, blocking the recruitment of antiviral immune cells by host chemokines, as well as viral chemokines that may act instead as agonists chemoattracting either more target cells for infection or Treg and Th2 cells that foster a proviral immunoregulatory environment. In addition, herpesvirus chemokines have been identified that may act as direct mediators of viral cell entry. Therefore, viral chemokines may provide novel therapeutic targets to inhibit herpesviruses directly at the levels of infection and dissemination, as well as indirectly by promoting a heightened antiviral immune response. In addition, antagonistic viral chemokines could conceivably be used directly as biologic response modifiers to attenuate pathologic inflammatory responses in settings such as autoimmunity and allotransplantation. In this regard, a detailed understanding of the basic molecular and cellular properties of herpesvirus chemokines is an important prerequisite for safe and effective translation to application in the clinic.

CHEMOKINES ENCODED BY CMVs

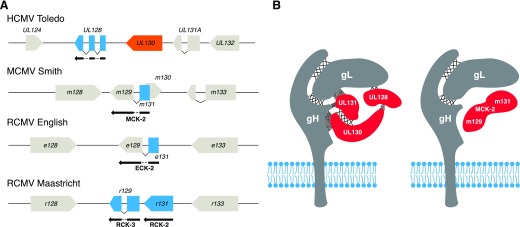

Although HCMV infection is generally asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals, it may cause severe retinitis, pneumonia, hepatitis, and encephalitis, among other pathologies, in immunocompromised hosts [22]. In addition, HCMV is the leading infectious cause of congenital disorders. Approximately 0.5–1% of newborns is infected annually with HCMV by vertical transmission from their mothers, 25% of whom may develop serious health problems during infancy, including vision or hearing loss [23, 24]. Furthermore, HCMV is the primary viral cause of complications during solid organ transplantation that may result in graft rejection and be life threatening [25]. Currently, there is no effective vaccine licensed for HCMV. In this regard, the enormous genetic variability of HCMV is a significant barrier to progress. With >0.025 substitutions per site, HCMV is clearly the most divergent HHV [26]. In addition, different HCMV strains may coinfect the same host, which may accelerate the emergence of new recombinant strains and complicate the design of effective vaccines and treatments [27–29]. HCMV sequence variation is particularly high in select genomic areas, including the UL/b′ region, where several viral chemokine genes are located [30, 31]. In this regard, ORF UL146, which encodes vCXCL1, is one of the most polymorphic genes of HCMV [32, 33]. Other viral chemokine genes in this region, such as those located in the UL128-UL131A locus, are very conserved and stable across isolates yet may rapidly acquire truncations or other deleterious mutations when the virus is cultured in vitro [34, 35]. UL146 and UL128-UL131A orthologs are found in nonhuman primate CMVs. In contrast, whereas UL 146 is not conserved in nonprimate CMVs, syntenic, putative homologs of HCMV chemokines UL128 and UL130 have been identified in MCMV and RCMV (Fig. 1A). However, surprisingly, these syntenic chemokines display diverse patterns of genomic organization and extremely low amino acid sequence identity so that they cannot be considered as orthologs. This raises interesting questions about the ancestral origin of these ORFs and the evolutionary history of the CMV species. Nevertheless, as detailed in the following sections, chemokines encoded by this region of the HCMV and MCMV genomes are components of a glycoprotein complex in the viral envelope that appears to mediate cell entry (Fig. 1B)—a function that has not been described for any other chemokine.

Figure 1. CMV syntenic chemokines.

(A) Schematic representation of the genomic distribution of viral chemokines in a syntenic region of the genomes of HCMV (Toledo strain), MCMV (Smith strain), and RCMV (English and Maastricht strains). Gray boxes correspond to nonchemokine ORFs; blue boxes indicate viral ORFs with CC chemokine homology. UL130 ORF, a C chemokine, is represented as an orange box. Splicing events are shown as connecting lines between boxes. CC chemokine names that differ from that of the ORF are indicated below the protein products (black arrows). (B) Models of viral envelope cell-entry complexes of HCMV Toledo and MCMV Smith containing viral chemokine homologs. Crossed lines and dots between proteins indicate covalent and noncovalent interactions, respectively. The HCMV diagram represents a combination of the protein–protein interactions proposed in the literature for this pentamer [43–46]. The MCMV diagram represents a trimeric protein complex based on the studies of Wagner et al. [76], who showed that the MCK-2 from MCMV Smith interacts with the gH/gL envelope dimer. The nature of the protein–protein interactions of gH/gL/MCK-2 has not been delineated yet. Blue phospholipid bilayers represent the viral envelope.

UL128

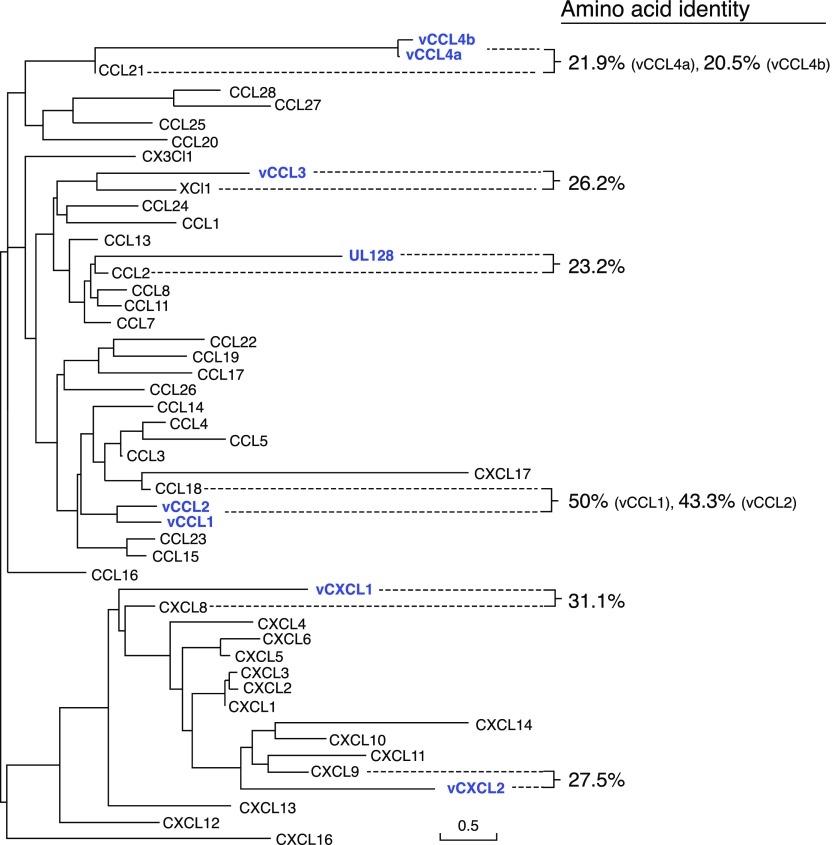

ORF UL128 of HCMV encodes a CC chemokine most highly homologous to human CCL2 (23.2% aa identity; Fig. 2). However, little is known about the activity of UL128, and its putative cellular receptor is unknown. To date, only 2 studies have been reported that have investigated the leukocyte chemotactic activity of UL128. In the first, it was reported to act as an antagonist, blocking primary human monocyte chemotaxis induced by CCL5 and CCL2 in vitro, as well as to down-regulate CCR1, CCR2, and CCR5 on monocytes [36]. In contrast, in the second study, it was reported to be a chemotactic agonist for human PBMCs in vitro [37]. There is precedent for the same chemokine acting as an agonist at one receptor and as an antagonist at another [38]; however, additional work defining specific receptors and using purified subsets of PBMCs will be needed to determine whether this is the case for UL128.

Figure 2. Human and HHV-encoded chemokine phylogeny.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis of human chemokines and chemokines expressed by HHVs using SeaView [228]. Alignment gaps were excluded from the analysis. Viral chemokines (UL128, gene UL128, HCMV strain AD169, UniProt Accession No. P16837; vCCL1, gene K6, KSHV isolate GK18, UniProt Accession No. F5HET8; vCCL2, gene K4, KSHV isolate GK18, UniProt Accession No. Q98157; vCCL3, gene K4.1, KSHV isolate GK18, UniProt Accession No. F5HCJ2; vCCL4a, gene U83, HHV-6A strain U1102, UniProt Accession No. P52460; vCCL4b, gene U83, HHV-6B strain Z29, UniProt Accession No. P52461; vCXCL1, gene UL146, HCMV strain Merlin, UniProt Accession No. F5HBX1; vCXCL2, gene UL147, HCMV strain Toledo, UniProt Accession No. Q68399) are highlighted in blue, and their amino acid identities to the most closely related human chemokine are indicated in the right column. Of note, vCXCL1 and vCXCL2 display high strain-to-strain variability; therefore, the phylogeny of chemokines from other HCMV strains might differ from the one presented here.

UL128 is 1 of 5 virally encoded components of a glycoprotein complex in the HCMV envelope that is essential for full infectivity in monocytes and epithelial and endothelial cells, among other cell types, but that is dispensable in fibroblasts [39–42]. The other 4 components are the transmembrane protein gH and the predicted secreted proteins gL, UL130, and UL131A (Fig. 1B). Whereas all published studies agree that gH and gL establish a covalent dimer, the interactions among the other components of the pentamer are subject to some controversy. Several reports support that UL128 and gL are linked by a disulfide bond to form a gH/gL/UL128 complex that interacts with UL130 and UL131A noncovalently [43–45]. However, the gL-UL128 disulfide bond was not detected in a second study, which instead, showed that UL128 is stabilized by noncovalent interactions with gL and a UL130-UL131A covalent dimer [46]. In Fig. 1B, we show a combination of these protein–protein interactions proposed for the pentamer. Although certain aspects of the pentamer’s biochemistry require clarification, it is nevertheless well established that the absence or mutation of any of its 5 components results in a mutant virus with impaired capacity to infect nonfibroblast cell types [42, 47, 48], possibly as a result of a defect in the export of the pentamer to the virus envelopment sites and subsequent incorporation into the virion [46]. Consistent with this, HCMV laboratory strains, such as AD169, which contains a 15 kb deletion of the UL/b′ genomic region affecting ORF UL131A [49], fail to express a competent pentamer and are unable to infect epithelial and endothelial cells [48, 50]. It is important to note that the gH/gL/UL128-UL130-UL131A complex is only one of the many glycoprotein complexes and viral proteins that mediate the intricate HCMV cell-entry process [51]. However, given its essential role in the infection of key cell types, the pentamer has become one of the most promising viral targets for the design of new vaccines and anti-HCMV antibody therapies [52–54].

UL130

A computational study concluded that another component of the HCMV pentamer, UL130, has molecular features of both C and CXC chemokines [55]. UL130 contains a signal peptide and like C chemokines, has a single cysteine residue at the N-terminus in addition to a second cysteine, conserved in CXC chemokines, in its putative 30s loop, potentially allowing for formation of a disulfide bond [55]. Despite this hybrid structure, the presence of a single cysteine at the N-terminus classifies UL130 as a C chemokine (Table 3). To date, evidence that UL130 can act as a soluble chemotactic factor has been lacking. In fact, this might be unlikely because UL130 has been characterized as a luminal protein in intracellular organelles that only exits the cell in association with the virion [56]. However, as with any other component of the pentamer, UL130 is essential for full HCMV infectivity in endothelial cells and for viral transmission to monocytes and leukocytes [42].

Thus, the HCMV envelope contains a cell-entry complex composed of 2 distinct viral chemokines—UL128 and UL130—with the potential to interact with diverse target cell types, as determined by the cellular distribution of host receptors specific for each viral chemokine. However, the precise mechanism of action of the pentamer and its binding partner(s) on the cell surface remains to be elucidated. As a promising target for novel anti-HCMV treatments and vaccines [52, 54, 57], identification of cell surface factors that bind components of the pentamer is an important research goal that might lead to new, therapeutic targets and strategies for treating and preventing HCMV infection by blocking cell entry. Moreover, pentamer components might be suitable as vaccine antigens for the prevention of congenital HCMV infection, which has been listed by the Institute of Medicine as a public health priority [58, 59]. In this regard, non-HCMVs, such as GPCMV, RhCMV, and CCMV, whose cellular tropism is also determined by a pentameric complex homologous to that of HCMV [60–65], could be particularly useful models [66–69]. Importantly, it has been reported that the GPCMV pentamer homolog (gH/gL/GP129-GP131-GP133) is essential for viral transmission from mother to fetus. In particular, GPCMV, carrying detrimental mutations in GP129 (UL128 homolog), showed an impaired ability to cause congenital infections [70, 71]. One possible explanation for this phenotype is that a functional pentamer is required for full infectivity in cytotrophoblasts, the main placental cell type infected by HCMV [72–74]. Consistent with this, neutralizing antibodies to components of the pentameric complex block HCMV cytotrophoblast infection [75]. Therefore, the targeting of the HCMV pentamer may be an efficient strategy to dampen the ability of the virus to cross the placenta and infect the fetus.

MCK-2 (m131/m129)

Most CMVs encode 2 or more chemokines; however, MCMV encodes only 1: the CC chemokine MCK-2. Like HCMV UL128, MCK-2 also forms a viral envelope complex associated with the MCMV counterparts of HCMV gH and gL that is necessary for infection of macrophages in vitro and in vivo [76, 77] (Fig. 1B). However, the nature of the protein–protein interactions in the gH/gL/MCK-2 complex has not been characterized yet (Fig. 1B). Of note, MCK-2-mediated cell tropism has been observed and biochemically characterized only in the MCMV Smith strain, whereas the K181 strain infects macrophages in an MCK-2-independent manner [78, 79].

MCK-2 is unique among chemokines as a result of its extended C-terminal domain. Full-length MCK-2 is translated from a spliced transcript that includes ORFs m131 and m129 (Fig. 1A) [80]. m131 encodes the N-terminal CC chemokine domain, whereas the C-terminal amino acid sequence deduced from m129 lacks significant homology to all other known proteins. It has been proposed that MCK-2 binds to the gH/gL complex through its m129 domain [76], and very recently it was shown that m129 is indispensable for MCK-2 glycosaminoglycan-dependent oligomerization [81], a biochemical capability with important implications in the bioactivity of most chemokines in vivo [82]. This might explain why a recombinant MCMV, derived from a commonly used bacmid, termed pSm3fr, which carries a frameshift mutation in m129, presents a reduced capacity to infect host salivary glands [83].

With regard to potential roles for MCK-2 as an immunomodulator, recombinant MCMV lacking MCK-2 elicits a markedly reduced inflammatory response at the site of infection and fails to recruit inflammatory monocytes, which are known to dampen the anti-MCMV CD8+ T cell response and to facilitate viral dissemination [84–86]. Interestingly, the MCK-2-induced inflammatory response is regulated by the MCMV deubiquitinase M48 [79]. However, the molecular mechanisms responsible for these effects, including the identity of the MCK-2 cellular receptor, have remained elusive. In the only report to date of direct actions on leukocytes, synthetic MCK-2 was reported to induce calcium flux in primary mouse macrophages from peritoneal exudates [87]. Consistent with this, recombinant MCK-2 induced a transient inflammatory response when injected into the mouse footpad [85]. It is well established, however, that MCK-2 is required for MCMV infection of host salivary glands [77, 83, 84, 88]. Although the mechanism of this phenotype is not completely understood yet, it is possible that both—MCK-2 immunomodulatory activity and its role in viral tropism—contribute to MCMV infection of salivary gland. This is important because the salivary glands are the main MCMV replication reservoir and are thought to be the primary source for viral transmission [89].

ECK-2 (e131/e129), RCK-2 (r131), and RCK-3 (r129)

Among the syntenic viral chemokines encoded by HCMV, MCMV, and RCMV (Fig. 1A), MCK-2 and RCMV ECK-2 form the most likely pair of actual orthologs. The E in ECK-2 denotes the English strain of RCMV in which its molecular properties were worked out [90]. ECK-2 has the same genomic organization as MCK-2, consisting of 2 ORFs (e131 and e129) that are syntenic and spliced similarly to MCMV ORFs m131 and m129 (Fig. 1A). The amino acid sequence identity between full-length ECK-2 and MCK-2 is 28% [90], the highest across all other possible protein pairs of the syntenic CMV chemokines, whose amino acid identities are from 10 to 20.5% [91]. The biochemical and biologic properties of ECK-2 have not been reported yet. Surprisingly, unlike their counterparts in MCMV and the English strain of RCMV, the r131 and r129 ORFs of the RCMV Maastricht strain encode 2 separate CC chemokines, RCK-2 and RCK-3, respectively (Fig. 1A). RCK-2 is an unspliced chemokine, 20.5% identical at the amino acid level to MCK-2, and like MCK-2, it is indispensable for persistent viral infection of the salivary gland [91]. RCK-3, which was unnoticed in the initial sequencing of the RCMV Maastricht genome [92], is most highly related to HCMV UL128 (but still having only 17.7% aa identity) [65, 91]. Recombinant RCK-3 has been reported to induce chemotaxis of primary rat macrophages and lymphocytes, including both naïve and central memory CD4+ T cells, and to bind to the rat chemokine receptors Ccr3, Ccr4, Ccr5, and Ccr7, showing the strongest binding to Ccr3 [93]. To date, the loop has not been closed by demonstrating whether this chemokine induces primary rat leukocyte chemotaxis by binding to one or more of these receptors, and its role in the pathogenesis of RCMV infections remains to be elucidated. Nevertheless, RCK-3 was associated with rapid rejection and vascular sclerosis of heart transplants in a rat model. Transplant recipient rats infected with an RCK-3-defective RCMV mutant showed a markedly reduced inflammatory cell infiltrate in the allograft and an extended rejection time, suggesting a proinflammatory activity for RCK-3 [93].

Unlike their HCMV and MCMV syntenic counterparts, the possible implication of RCMV-encoded chemokines in viral cell entry has not been investigated yet. It will be important to clarify whether these cell-entry chemokines can also act as secreted or viral envelope-associated chemotactic factors during infection. Several shared properties of these chemokines suggest that they may, including that 1) all CMV CC chemokines have an N-terminal signal peptide, 2) they all present the canonical structural features of the chemokine fold, and 3) recombinant forms of some of these CMV chemokines have been shown to modulate leukocyte migration. However, for most of these chemokines, it is not well established whether in the context of infection, they are deployed exclusively in viral envelope complexes or whether a fraction may also be secreted in soluble form.

vCXCL1 (UL146)

HCMV ORFs UL146 and UL147 encode vCXCL1 and vCXCL2, respectively, the only 2 known herpesvirus CXC chemokines [94]. UL146 and UL147 are located within the UL/b′ genomic region of HCMV clinical isolates but are absent in attenuated lab strains [49]. This suggests that vCXCL1 and vCXCL2 are dispensable in vitro but may contribute to HCMV pathogenesis in vivo. They are 20.3% identical to each other at the amino acid level and are most highly related to human CXCL8 (31.1% identity) and CXCL9 (27.5% identity), respectively (Fig. 2).

vCXCL1 is an agonist at the closely related human neutrophil receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2, with highest potency at CXCR2 [94, 95]. It is important to note that although vCXCL1 is a glycosylated chemokine [94], its functional characterization was performed using nonglycosylated recombinant protein expressed in bacteria. A recent study has shown that vCXCL1 can also bind to CX3CR1 and attract NK cells that express this receptor [96]. However, this was reported to be a very low-affinity interaction, and in chemotaxis assays, where NK cells mixed with neutrophils were incubated with vCXCL1, neutrophils migrated faster and were more predominantly recruited [96]. Therefore, neutrophils are the most likely target cells for vCXCL1 in vivo. Neutrophils are known to contribute to the vascular dissemination of HCMV [97]. Upon HCMV infection, endothelial cells may produce chemokines that recruit neutrophils that then become infected during transendothelial migration [98]. In this context, vCXCL1 may collaborate with host chemokines to attract neutrophils and promote viral dissemination. Therefore, anti-vCXCL1 clinical strategies might be useful to impair an important mechanism for HCMV dissemination.

vCXCL1 conserves the N-terminal ELR amino acid motif found in all host chemokines that target the neutrophil chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 [8]. In fact, although UL146 is one of the most structurally diverse HCMV genes (up to 60% aa variability across strains), the ELR motif of vCXCL1 is conserved across clinical isolates [32, 99–101]. However, clinical variants of vCXCL1 differ considerably in their agonist activities, and specific variants have been associated with different clinical phenotypes (e.g., CNS damage, hepatomegaly) [102, 103]. Not all studies have found a clear vCXCL1 variant–disease association [104]; therefore, additional and larger studies will be needed to delineate more fully and precisely the impact of vCXCL1 variation on clinical outcome during HCMV infection.

Whereas absent from rodent CMVs, vCXCL1 orthologs are found in most nonhuman primate CMVs [105–107]. Importantly, the UL146 locus displays significant genomic structure variability across primate CMV species, which results not only in a high protein sequence diversity but also in a variable number of CXC chemokine ORFs. For instance, whereas vCXCL1 and vCXCL2 are the only CXC chemokines identified in HCMV, the UL/b′ genomic region of some wild-type isolates of RhCMV and CCMV contains up to 6 and 3 different putative CXC chemokines, respectively, which may reflect diverse immunomodulatory needs adapted to the specific hosts of these viruses [105, 106]. Functional characterization of RhCMV chemokines is missing, but the UL146 ortholog in CCMV encodes an active chemokine that shares the activity properties of HCMV vCXCL1, although it binds to CXCR2 with lower affinity [108].

vCXCL2 (UL147)

Unlike vCXCL1, the putative cellular receptor and signaling potential of vCXCL2 have not yet been characterized (Table 3). vCXCL2 is more highly conserved among HCMV strains than vCXCL1 (∼15 vs. ∼60% aa variability, respectively) [33]. Furthermore, most vCXCL2 variation in clinical isolates is clustered within the signal peptide sequence, which does not affect mature protein structure or function [32]. Like vCXCL1, some vCXCL2 genotypes have been associated with worse clinical outcomes in infected children [103]. Unlike vCXCL1, vCXCL2 does not have an ELR motif. Instead, vCXCL2 is most highly related to CXCL9 (27.5% identity; Fig. 2), a CXCR3 ligand, and has a variant DXR motif, where X is an Arg or Lys, which might interfere with function [32]. Future studies should investigate whether vCXCL2 might be an antagonist or a ligand specific for other members of the CXC chemokine receptor subfamily or even other subgroups of GPCRs.

vXCL1 (e156.5)

Recently, the first virally encoded C chemokine homolog, vXCL1, was identified in the English strain of RCMV, ORF e156.5 [109]. vXCL1 displays very high amino acid sequence identity with its human (46%), mouse (58%), and rat (64%) host counterparts and like XCL1, binds specifically to XCR1-expressing cells [109]. In mouse, cellular Xcr1 expression is restricted to a splenic subset of CD8+ DCs that migrate toward Xcl1 [110]. CD8+ DCs play an important role in the adaptive immune response against viral infections through antigen crosspresentation and activation of both NK cells and CD8+ T cells [111]. In rat, splenic CD4− DCs are thought to be equivalent to mouse CD8+ DCs [112]. Accordingly, it has been reported that vXCL1 is a chemoattractant for CD4− DCs but not for other DC subsets, with a potency and efficacy similar to that of rat Xcl1 [109]. To date, there are no data defining the clinical, immunologic, and virologic functions of vXCL1 in the context of RCMV infection in vivo. The fact that vXCL1 orthologs have not been found in other CMV species, including the closely related RCMV Maastricht strain, suggests a special interest by RCMV English in hindering Xcr1-mediated activities. It is important to note that although KSHV vCCL3 has also been reported to be an XCR1 agonist (vide infra), a key differential feature is that unlike vXCL1, vCCL3 has not been demonstrated to induce chemotaxis of DC. In addition, vCCL3 can act as a weak agonist at CCR4, and vXCL1 but not vCCL3 mimics the main amino acid sequence features of host Xcl1. Therefore, a priori, vXCL1 seems to be better designed than vCCL3 to interfere specifically with the Xcl1–Xcr1 signaling axis.

CHEMOKINES ENCODED BY THE ROSEOLOVIRUSES HHV-6A AND HHV-6B

Ironically, although HHV-6 was one of the last HHVs to be discovered [113], it was the first one in which a viral chemokine gene was identified: HHV-6 ORF U83 [114, 115]. HHV-6 is arguably the most widespread HHV, with extremely high prevalence rates (70–100%) across all racial groups (Table 1) [116]. Most HHV-6 infections occur before 2 yr of age and typically produce self-limited febrile episodes occasionally followed by a characteristic maculopapular skin rash referred to as exanthem subitum or roseola [117, 118]. Primary infections may rarely evolve into more severe clinical outcomes, including encephalitis, meningitis, hepatitis, or lymphadenopathy [119–124]. After the acute phase of infection, HHV-6 establishes a lifelong latent infection in the host. In healthy adults, HHV-6 has not been clearly defined as a cause or cofactor of any specific disease, although several studies have reported a potential link between HHV-6 infection and MS [125]. In contrast, in immunocompromised individuals, HHV-6 reactivation may cause encephalitis and other neurologic and inflammatory disorders [126].

HHV-6 and HHV-7 form the genus Roseolovirus named after the skin rash. HHV-6 consists of 2 variants, HHV-6A and HHV-6B, which have been proposed to be separate species based on their genetic characteristics and differences in pathogenesis, cell tropism, and geographical distribution [127]. In Europe, the United States, and Japan, the vast majority (97%) of HHV-6 infections in infants are caused by HHV-6B, whereas in sub-Saharan Africa, asymptomatic pediatric infections with HHV-6A are more frequent (86%) [128–130]. However, febrile episodes and roseola are predominantly caused by HHV-6B, even in Africa. No disease has been clearly attributed to HHV-6A in immunocompetent individuals, although several studies indicate that it is more strongly associated with neuroinflammatory conditions than HHV-6B [131–133]. The broader cellular tropism of HHV-6A may explain this. Whereas both HHV-6A and HHV-6B are neurotropic and display a marked cellular tropism for CD4+ T cells, HHV-6A also infects CD8+ T, NK, and γδ T cells, whereas HHV-6B infection of these cell types is quite inefficient [134]. Furthermore, microglial cell lines are more susceptible to HHV-6A infection in vitro [135].

vCCL4 (U83)

ORF U83 encodes a functional CC chemokine and is one of the few hypervariable genes (13% sequence variation) between HHV-6A and HHV-6B [136], which may account for the striking specificity and activity differences between the products of U83A and U83B. Accordingly, we propose that the products of U83A and U83B should be designated vCCL4a and vCCL4b, respectively, denoting that they are CC chemokines encoded by homologous genes but have different activities. Importantly, there is no U83 homolog in HHV-7, which can be used as a way to differentiate roseoloviruses [137]. vCCL4 is the only chemokine encoded by HHV-6, but it also expresses 2 active GPCRs, U12 and U51, which are homologous to the HCMV-encoded orphan vGPCRs, UL33 and UL78, and transmit signals by the host chemokines CCL2, CCL4, and CCL5 and CCL2, CCL5, CCL7, CCL11, CCL13, CCL19, and XCL1, respectively [138–140] (Table 2). These 2 GPCRs, together with vCCL4, may sufficiently equip HHV-6 to interfere competently with host chemokine signaling at all stages of infection.

vCCL4a and vCCL4b are both most homologous to human CCL21 (only 21.9 and 20.5% aa identity, respectively; Fig. 2), a chemokine ligand for CCR7. However, neither of these viral chemokines has been shown to bind CCR7. Instead, vCCL4b is a selective agonist for CCR2 and a proven chemoattractant for monocytes [115, 141]. Compared with host chemokine ligands for CCR2, vCCL4b has 25- to 1000-fold lower receptor-binding affinity and 10- to 200-fold lower potency for inducing intracellular calcium flux signals [141]. As CCR2 is highly expressed on monocytes, which constitute an important reservoir for HHV-6 latency [142], vCCL4b could facilitate viral latency by recruiting monocytes to sites of infection.

In contrast to vCCL4b, vCCL4a of HHV-6A interacts more promiscuously with host chemokine receptors, inducing calcium flux and chemotaxis by signaling through CCR1, CCR4, CCR5, CCR6, and CCR8, with similar potencies as those for the endogenous host chemokine ligands for these receptors [143]. It has been proposed that the broader receptor specificity of vCCL4a over vCCL4b may determine the pathogenesis and cell tropism differences observed between HHV-6A and HHV-6B, by attracting a greater variety of cell types to sites of infection [144]. Besides their direct agonist activities, these viral chemokines may further disrupt chemokine signaling by decreasing the internalization rates of their target receptors, thereby delaying receptor recycling and the subsequent re-exposure of free receptor molecules on the cell surface [145]. In addition, vCCL4a does not interact with ACKR1 and ACKR2 [146], which are members of a small subgroup of chemokine receptors that bind and sequester chemokines from the extracellular compartment without triggering G protein activation [147]. The ability of vCCL4a to elude these scavenger receptors may provide a significant competitive advantage over the endogenous host ligands, which can all be sequestered by ACKRs.

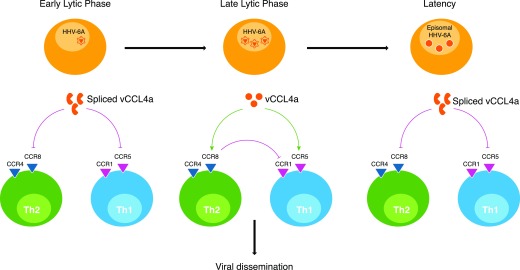

HHV-6 ORF U83 is known to be regulated by splicing during lytic and latent infection. This results in the production of 2 different chemokine forms: full-length and truncated vCCL4, which differ in their expression kinetics. Whereas full-length vCCL4 proteins accumulate late after cell infection, truncated forms of the chemokine are expressed early during lytic infection and during latency, independently of viral replication [136, 143]. These truncated variants keep the chemokine N-terminal domains unaltered, which allows them to maintain the binding specificity of full-length vCCL4. Interestingly, unlike the short form of vCCL4b, which is functionally indistinguishable from the full-length chemokine, truncated vCCL4a acts as a potent antagonist of the cellular receptors activated by full-length vCCL4a [143, 144]. This suggests the interesting possibility that HHV-6A may use vCCL4a to skew the immune response to a specific proviral state that optimizes a given stage of infection (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, unlike for the episomal latent virus, full-length vCCL4 is the predominant form of the chemokine expressed by chromosomally integrated HHV-6 [148]. Although HHVs typically establish latency as episomes in the host cell nucleus, HHV-6 is the HHV with the highest prevalence of chromosomal integration in the germline (1%) [149]. Consequently, vCCL4 and other HHV-6 genes could theoretically be expressed in every cell and contribute to the pathogenesis of diverse diseases. Although the clinical complications resulting specifically from integration of HHV-6 genomes have not been clearly delineated, they have been associated with a higher rate of graft rejection and with cardiomyopathy and neuroinflammatory conditions [148, 150, 151]. Chronic expression of a proinflammatory factor, such as vCCL4, could contribute to the development of these diseases. Unfortunately, the absence of a valid HHV-6 animal model precludes a more detailed study of the role that these molecules may play in viral pathogenesis.

Figure 3. Model of action of spliced and full-length vCCL4a during HHV-6A infection.

HHV-6A vCCL4a is differentially regulated by splicing during the distinct phases of viral infection. A truncated chemokine (spliced vCCL4a) is expressed independently from viral replication during the early lytic phase or latency, whereas full-length vCCL4a is accumulated when active viral replication occurs (late lytic phase). Both spliced and full-length vCCL4a interact with the same chemokine receptors (CCR1, CCR5, CCR4, and CCR8) but acting as antagonist or agonist, respectively. This may allow a selective control of immune cell migration, selectively benefiting distinct phases of the infection. During the early lytic phase, spliced vCCL4a may inhibit the recruitment of immune cells to facilitate the completion of the viral lytic cycle. Then, the full-length chemokine may attract lymphocytes for lytic or latent infection and subsequent viral dissemination, while recruiting CCR4- and CCR8-bearing Th2 cells that dampen the antiviral activity of Th1 cells recruited by the chemokine through CCR1 or CCR5. Once latency has been established (episomal HHV-6), the immune response may be inhibited by re-expression of spliced vCCL4a, shielding the silent state of the chronic infection. This model is based on the studies published by French et al. [136] and Dewin et al.[143].

On the other hand, the truncated vCCL4a form, a naturally occurring receptor inhibitor, may be useful therapeutically. In particular, it is able to block infection of target cells with R5-tropic HIV strains [145]. In addition, as vCCL4 receptors CCR1, CCR2, CCR5, CCR6, and CCR8 have all been implicated in MS [152], it is relevant to study whether vCCL4 might be involved in the pathogenesis of HHV-6-associated MS and whether the inhibitory spliced form of vCCL4a might have therapeutic efficacy in MS, as well as other inflammatory conditions in which these chemokine receptors have been implicated.

CHEMOKINES ENCODED BY KSHV

KSHV is a γ-herpesvirus and the causative agent of the eponymous KS, a multicentric HIV-associated angioproliferative tumor that typically appears in the skin but can also affect mucosal sites and internal organs, potentially causing life-threatening conditions [153]. Although KS can occur in HIV-negative individuals in some sub-Saharan African regions (endemic KS), in elderly Mediterranean populations (classic KS) or as a complication in graft recipients (iatrogenic KS), its most severe manifestations are usually associated with HIV infection (epidemic KS) [154]. In fact, KS is an AIDS-defining condition in HIV-seropositive patients.

KSHV is arguably the least prevalent HHV (Table 1). Although KSHV prevalence rates may spike to 50% in third-world regions with a high incidence of HIV, they have remained stably under 5–10% in most industrialized countries [155]. Two other rare disorders are caused by KSHV, especially in immunosuppressed individuals: multicentric Castleman disease, a noncancerous lymphoproliferative disorder, and primary effusion lymphoma, an HIV-associated B cell cancer [156]. Unlike EBV, which may cause tumors by inducing malignant cell transformation, KSHV-induced tumors are typically polyclonal and primarily characterized by their angiogenic and inflammatory nature [157]. Indeed, KSHV has been defined as the etiological cause of a nononcological systemic inflammatory disorder, termed KICS [158]. KSHV genes involved in immunomodulation and inflammation include a potent IL-6 homolog (viral IL-6), a viral chemokine receptor (vGPCR or ORF74), and 3 functionally distinct viral chemokines (vCCL1, vCCL2, and vCCL3) [159].

vCCL1 (K6)

vCCL1 (originally named vMIP-I) is encoded by ORF K6 of KSHV and has 37.9% identity at the amino acid level to human CCL3 (formerly MIP-1α) [160], but it is most highly related to CCL18 (50% identity), a CCR8 ligand (Fig. 2). Some controversial data exist about the activity of this viral chemokine. Consistent with its CCL3 homology, vCCL1 has been reported to be a ligand for the CCL3 receptor CCR5 based on its ability to induce calcium flux in CCR5-transfected K562 cells and to inhibit replication of some R5 tropic HIV strains [160, 161]. In addition, vCCL1 has been reported to induce monocyte chemotaxis in vitro and to block HIV infection of cells transfected with the minor HIV coreceptors CXCR6, GPR-1, and CCR3 [161, 162]. However, other published studies have not reproduced these results [163, 164]. In contrast, consistent with its highest amino acid identity to CCL18, vCCL1 has been reproducibly shown in 3 independent and comprehensive studies to be a specific CCR8 ligand and agonist, binding with an affinity that is ∼7-fold lower than that for the endogenous CCR8 ligand CCL1 [164–166]. vCCL1–CCR8 signaling is hypothesized to affect KSHV pathogenesis in several ways. First, vCCL1 could skew the immune system toward a proviral state by recruiting Tregs [167], which are known to accumulate in KS lesions [168], as well as Th2 cells. A direct effect of vCCL1 on migration and/or activation remains to be established for Th2 cells, which are abundant in KS lesions but preferentially express CCR3 and CCR4 and have been proposed to be recruited by a vCCL2-mediated mechanism [169]. Second, vCCL1 might protect infected cells from apoptosis, facilitating the productive replication of KSHV. Consistent with this possibility, vCCL1 has been reported to mimic the CCR8-mediated anti-apoptotic activity of host CCL1 in dexamethasone-treated BW5147 lymphoma cells [170]. Third, vCCL1 could promote vascular dissemination of the virus in KS by promoting angiogenesis. Consistent with this, vCCL1 is a potent chemoattractant for vascular endothelial cells, which are known to express CCR8 [171], and has been shown to induce angiogenesis when applied to chicken chorioallantoic membranes [163]. vCCL1 provides a striking contrast to ORF MC148 of the molluscum contagiosum virus, which encodes the only known poxvirus chemokine, a CC chemokine that is a specific antagonist at human CCR8 [15]. Of note, another poxvirus, yaba-like disease virus, also targets this chemokine signaling axis by the expression of 7L, a chemokine receptor for human CCL1. Therefore, CCR8 appears to be a target of interest for many viral anti-chemokine strategies, which suggests that this chemokine receptor may play an important role in viral pathogenesis and in host antiviral responses.

vCCL2 (K4)

KSHV ORF K4 encodes vCCL2 (also called vMIP-II) [160], at present, the best-characterized viral chemokine. Despite its high structural relatedness to vCCL1 (56.5% aa identity), these 2 proteins exert completely different activities. vCCL2 is a highly promiscuous chemokine receptor antagonist at CCR1, CCR2, CCR5, CCR10, CXCR4, CX3CR1, and XCR1 [166, 172, 173]. In addition, vCCL2 has been reported to act as a chemotactic agonist at CCR3 and CCR8 to recruit Th2 cells to KS lesions [163, 169, 174]. Thus, by blocking recruitment of Th1 cells expressing CCR1, CCR5, and other Th1-biased chemokine receptors and by attracting CCR3- or CCR8-bearing Th2 cells, vCCL2 would be well suited to skew the immune response toward Th2, favoring KSHV persistence. It is important to note, however, that several other studies have reported vCCL2 to be an antagonist at CCR3 and CCR8 [165, 166, 172]. Therefore, further experimentation is required to clarify the agonist potential of vCCL2. Importantly, the receptor promiscuity of vCCL2 allows it to block migration of immune cells at different stages of differentiation or activation. For example, NK cells, which predominantly use CX3CR1 to exit the bone marrow and switch to CCR5 upon activation, can be targeted by vCCL2 in both contexts [175]. Furthermore, very recently, vCCL2 was identified as a ligand for ACKR3 (previously known as RDC1 and CXCR7, which may signal through an arrestin pathway), an interaction that does not induce cell chemotaxis but might regulate the availability of vCCL2 in the extracellular compartment [176].

In addition to binding specific host chemokine receptors, KSHV vCCL2 binds the viral chemokine receptors US28 and U51, encoded by HCMV and HHV-6, respectively [140, 172] (Table 2). As these viruses infect humans with high prevalence rates, they could conceivably all coinfect the same host and coregulate each other, in part, through direct cross-interacting chemokine pathways. Importantly, vCCL2 binds and down-regulates the product of KSHV ORF74, vGPCR [177, 178], a CXCR2-like chemokine receptor that binds multiple host CC and CXC chemokines but also induces ligand-independent constitutive signaling associated with the massive cell proliferation characteristic of KSHV infection [159, 179]. It has been proposed that the down-regulation of vGPCR by vCCL2 could be important to ensure immune evasion during specific phases of infection [180].

vCCL2 is the only chemokine, host or viral, reported to bind to members of all 4 subgroups of chemokine receptors, which is, as yet, an unsolved structure-function puzzle. Some of the molecular determinants were defined by solution of the crystal structure of a vCCL2:CXCR4 complex, which together with CX3CL1:US28, are the only crystals of a chemokine ligand:receptor complex that have been resolved so far [181, 182].

Unlike other viral chemokines whose potential clinical uses as antiviral or anti-inflammatory factors are still mostly theoretical, vCCL2 has been the subject of extensive preclinical testing in inflammatory, infection, and transplantation models. The broad inhibitory spectrum of vCCL2 suggests that it could be a particularly effective anti-inflammatory factor in vivo. Consistent with this, recombinant vCCL2 diminished cell infiltration and inflammation in animal models of spinal cord injury, glomerulonephritis, and cutaneous hypersensitivity, as well as recruitment of Th1 cells during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection [183–186]. As vCCL2 binds to the major HIV coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5, it is not surprising that it inhibits HIV infection in cells expressing these coreceptors; however, unexpectedly, it is more potent against CCR3-mediated HIV infection [172]. As CCR3 is thought to act as an HIV coreceptor, mainly in microglia in the CNS [187], it was proposed that vCCL2 may lower the risk of AIDS-related dementia in patients coinfected with KSHV [163]; however, this association remains controversial. Preclinical studies have shown that vCCL2 can control SIV infection in vivo [188], which provides proof of principle for development and application of vCCL2-based anti-HIV peptides. Interestingly, vCCL2-derived N-terminal peptides have been identified that lack CCR5 specificity while retaining CXCR4 specificity [189, 190]. Thus, these peptides are candidate-specific inhibitors of X4 strains of HIV [191]. Like vCCL1, vCCL2 induces angiogenesis in egg chorioallantoic membranes [163]. Therefore, these 2 chemokines may contribute together to the high degree of vascularity characteristic of KS lesions, and may facilitate KSHV dissemination during infection. Importantly, the angiogenic properties of vCCL2 were also demonstrated in mouse models by transfer of Matrigel-embedded endothelial cells transduced with vCCL2 [192]. The combination of its anti-inflammatory and angiogenic properties make vCCL2 an appealing agent to promote allograft survival in the transplantation area. In fact, vCCL2 has been shown to enhance survival of cardiac, pancreatic, kidney, and corneal allografts in animal models [192–195].

vCCL3 (K4.1)

ORF K4.1 encodes the third KSHV chemokine, vCCL3 (previously called vMIP-III) [172], which is distantly related to vCCL1 and vCCL2 (25–28% identity at the amino acid level). The closest human homolog is XCL1 (26.2% aa identity; Fig. 2). Initially, vCCL3 was described as a low-potency but highly efficacious agonist at human CCR4, which is typically expressed in Tregs and Th2 cells [196]. Accordingly, it was shown that vCCL3 induced chemotaxis preferentially of Th2- over Th1-polarized cells [196]. This suggested the possibility that vCCL3 might act in synergy with vCCL1 to recruit anti-inflammatory Th2 cells to sites of KSHV infection through a mechanism mediated by CCR4 or CCR8, respectively. However, it is important to note that these effects of vCCL3 at CCR4-expressing cells required micromolar concentrations of vCCL3 (0.1–10 μM). In contrast, consistent with its highest identity to XCL1, a more comprehensive analysis revealed that nanomolar concentrations of vCCL3 (0.1–10 nM) induced signaling and chemotaxis of XCR1-transfected cells, what represents a 10-fold-higher potency compared with XCL1 [166]. Therefore, vCCL3 activity in vivo may be mediated predominantly by XCR1, which is selectively expressed by a subpopulation of DCs specialized in antigen cross-presentation to CD8+ T cells [110]. As in the case of the RCMV-encoded vXCL1, which also mobilizes XCR1-expressing DCs, at first, it may appear counterintuitive that a virus would encode a chemokine that recruits DCs, which may initiate antiviral CD8+ T cell responses; however, KSHV has also evolved multiple strategies to hijack antigen-presentation mechanisms [197, 198]. The main selective feature may involve the capacity of DCs to serve as a reservoir for KSHV latency [199]. However, more experimentation is required to confirm that vCCL3 actually attracts DCs in vivo and how the activity of these cells is modulated by vCCL3 or other immunoregulatory factors encoded by KSHV.

In summary, KSHV encodes 3 different viral chemokines that display specific agonistic (vCCL1 and vCCL3) or broad-spectrum antagonistic (vCCL2) effects on cell migration. Together with KSHV vGPCR, these comprise a fully equipped arsenal to interfere with the normal functions of the host chemokine network. These 3 viral chemokines may work together to promote a Th2 response during KSHV infections by blocking the migration of Th1 cells and recruiting Th2 cells. However, besides their effects on immune cell-migration patterns, their anti-apoptotic and angiogenic properties might be fundamental for KSHV pathogenesis and contribute to the angiogenic and inflammatory nature of KSHV-associated tumors. In this context, KSHV-encoded chemokines and vGPCR may be essential pathogenic factors, as demonstrated by the fact that uninfected, vGPCR-transgenic mice develop KS-like lesions [200]. Therefore, these viral genes might constitute effective targets for the design of new antiviral and palliative therapies. However, it is important to note that KSHV did not evolve in humans to cause KS; therefore, some properties attributed to these viral chemokines may be accidental and not important to the normal life cycle of the virus.

CHEMOKINES PRODUCED BY OTHER HHVs

Although HHV-6 can infect the CNS and provoke neurologic disorders, the viral chemokines presented heretofore are encoded by HHVs that are generally described as lymphotropic. In contrast, none of the above-mentioned ORFs or putative homologs are conserved in the markedly neurotropic alphaherpesviruses. Likewise, viral chemokine receptors have not been identified in this HHV subfamily. Instead, alphaherpesviruses appear to rely on viral chemokine-binding proteins, not conserved in beta- or gammaherpesviruses, to hijack the host chemokine network. In particular, gG in HSV-1 and HSV-2, and gC in VZV bind multiple chemokines with high affinity enhancing their chemotactic activity [201, 202], which differs strikingly from the typical inhibitory effect of gG orthologs in nonhuman alphaherpesviruses and of poxvirus-encoded, chemokine-binding proteins [203–205]. Therefore, probably as a result of their distinct pathogenic mechanisms, lymphotropic and neurotropic HHVs have opted for different strategies to subvert or repurpose the host chemokine network. However, one chemokine homolog has been identified in alphaherpesviruses—gL—a viral envelope glycoprotein involved in cell entry.

gL

Herpesvirus cell entry is a complex process mediated in a cell type-dependent manner by multiple diverse viral glycoproteins in each HHV [206]. The core membrane fusion machinery, formed by gB and the gH/gL heterodimer, is conserved in all HHVs, whereas receptor-binding proteins differ among HHV species and ultimately define cellular tropism [207, 208]. Current entry models hold that the activation of gH/gL, through its direct binding to cellular receptors or by signals transmitted from other viral receptor-binding proteins, induces a gB conformational change that initiates membrane fusion [209, 210]. Additional viral proteins can interact with gH/gL to form different receptor-binding complexes in each HHV [211]. In fact, in betaherpesviruses, gH/gL dimers are efficiently exposed on the virion envelope only when in complex with other viral proteins [212–214]. By contrast, uncomplexed gH/gL dimers mediate alpha- and gammaherpesvirus entry into neurons and epithelial cells, respectively, through their binding to cellular integrins in alphaherpesviruses and EBV or ephrin type A receptor A2 in the case of KSHV [215–219]. Importantly, a computational analysis predicted that gL from these 2 HHV subfamilies adopts a classic chemokine fold (unorganized N-terminus, 3 β-strands, and 1 α-helix) [220], which was later confirmed by the 3-dimensional structures determined for the gH/gL dimer of HSV-2 and EBV [221, 222]. As described previously for HCMV UL130, gL from HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV, is a C chemokine homolog with a single disulfide bond conserved in CXC chemokines, whereas EBV and KSHV gL exhibits a classic CC chemokine topology [55, 220]. Interestingly, betaherpesvirus gL lacks chemokine homology [55, 220]. Instead, as presented before, HCMV gL can form a pentameric complex in association with the viral chemokines UL128 and UL130. Therefore, most HHVs present at least 1 chemokine homolog in their envelope involved in the cell-entry process. It would be interesting to explore whether either gQ1 or gQ2—HHV-6 glycoproteins that form a viral envelope tetramer with the gH/gL dimer of this betaherpesvirus [223]—displays chemokine structural homology.

Whether gL can act as a chemotactic factor or mediate viral cell entry through its interaction with chemokine receptors remains to be elucidated. Importantly, unlike transmembrane gH that needs gL to be folded and exposed efficiently on the virion surface [224, 225], gL contains a predicted N-terminal signal peptide and is secreted when expressed in the absence of gH [226]. Therefore, whether a soluble form of gL is expressed in the context of infection is an important subject for future investigation.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Although herpesviruses commonly copy and repurpose host chemokines, the reason why is not yet completely clear. Immune evasion is most likely, achieved by either broadly antagonizing leukocyte chemokine receptors to prevent trafficking and accumulation at the site of viral infection or by preferentially activating selected chemokine receptors to skew the immune response from a proinflammatory/antiviral Th1 state to an anti-inflammatory/proviral Th2 state (Fig. 4). KSHV may achieve this by coexpressing 3 different chemokines, whereas HHV-6A appears to use 2 functionally distinct forms of the same chemokine that are differentially expressed during infection. Another contribution to pathogenesis made by herpesvirus chemokines may involve attraction of cell types that support viral spreading or latency (Fig. 4). On the other hand, some activities of these viral chemokines appear to be antiviral in nature, a paradox that might be resolved by considering the numerous other strategies used by herpesviruses at many levels to subvert the host immune response.

Figure 4. Bioactivities of herpesvirus-encoded chemokines to support viral infection.

Summary of the agonistic (green arrows) or antagonistic (red arrows) potential activities of viral chemokines whose cellular receptors have been identified. Herpesviruses may express chemokine homologs to manipulate the migration patterns of different cell types with 3 major goals: 1) to skew the immune response from Th1 to Th2 by attracting Th2 cells (vCCL1, vCCL2, and vCCL4a) or by blocking the recruitment of Th1 cells (vCCL2); 2) to promote viral dissemination by recruiting target cells (neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, DCs, etc.); and 3) to facilitate the establishment of chronic infections by attracting cell types that support viral latency, such as macrophages (vCCL4b) or DCs (vXCL1 and vCCL3). Chemokines are color coded to indicate the corresponding HHVs (see “key”) in each case.

Whether viral chemokines directly promote viral infection, dissemination, and latency, is currently speculative, although some herpesvirus chemokines appear to have quite novel properties in this regard related to target cell entry. Herpesvirus chemokines almost certainly require additional viral and host factors to function, which probably include GPCRs, and some candidates have been identified. Despite large gaps in basic knowledge, research on herpesvirus chemokines has already provided new concepts for anti-HIV drugs and angiogenic agents in transplantation and cardiovascular disease, as well as the crystallographic structure of the first chemokine–chemokine receptor complex. In the future, additional work will need to be directed toward resolving the controversies surrounding the activities reported for several of the herpesvirus-encoded chemokines, which may result from artifacts introduced in the production of tagged recombinant viral chemokine proteins. Future efforts will also be needed to identify the relevant receptors and mechanisms of action for each viral chemokine, as well as their biologic roles in vivo. For herpesviruses, this is hampered by their extremely narrow natural host range, complicating interpretation of the results from experiments using animal models with non-natural hosts. Until the very recent discovery of the first mouse roseolovirus [227], HCMV was the sole HHV with clear homologs specific for other mammalian hosts. The study of these nonhuman herpesviruses in their natural hosts or HHVs in humanized animal models could help to clarify the relevance of herpesvirus chemokines in the context of a natural viral infection.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF: While this review was in press, the structure of the gH/gL/UL128-UL130-UL131A pentamer was published [258]. This new structure resolves the controversies about the biochemistry and protein-protein interactions of this complex discussed in this review.

AUTHORSHIP

S.M.P. and P.M.M. wrote the review.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Glossary

- ACKR

atypical chemokine receptor

- CCMV

chimpanzee cytomegalovirus

- DC

dendritic cell

- ELR

Glu-Leu-Arg

- GPCMV

guinea pig cytomegalovirus

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HCMV

human cytomegalovirus

- HHV

human herpesvirus

- HVS

herpesvirus saimiri

- KICS

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus inflammatory cytokine syndrome

- KS

Kaposi’s sarcoma

- KSHV

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus

- MCMV

mouse cytomegalovirus

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- ORF

open-reading frame

- RCMV

rat cytomegalovirus

- RhCMV

rhesus monkey cytomegalovirus

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- vCCL

viral CCL

- vCXCL

viral CXCL

- vGPCR

viral G protein-coupled receptor

- vXCL1

viral C motif chemokine 1

- VZV

varicella zoster virus

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arvin A., Campadelli-Fiume G., Mocarski E., Moore P. S., Roizman B., Whitley R., Yamanishi K., eds. (2007) Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloom D. C. (2016) Alphaherpesvirus latency: a dynamic state of transcription and reactivation. Adv. Virus Res. 94, 53–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ressing M. E., van Gent M., Gram A. M., Hooykaas M. J.., Piersma S. J., Wiertz E. J. (2015) Immune evasion by Epstein-Barr virus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 391, 355–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodrum F., Caviness K., Zagallo P. (2012) Human cytomegalovirus persistence. Cell. Microbiol. 14, 644–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grey F. (2015) Role of microRNAs in herpesvirus latency and persistence. J. Gen. Virol. 96, 739–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vossen M. T., Westerhout E. M., Söderberg-Nauclér C., Wiertz E. J. (2002) Viral immune evasion: a masterpiece of evolution. Immunogenetics 54, 527–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alcami A. (2003) Viral mimicry of cytokines, chemokines and their receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 36–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachelerie F., Ben-Baruch A., Burkhardt A. M., Combadiere C., Farber J. M., Graham G. J., Horuk R., Sparre-Ulrich A. H., Locati M., Luster A. D., Mantovani A., Matsushima K., Murphy P. M., Nibbs R., Nomiyama H., Power C. A., Proudfoot A. E., Rosenkilde M. M., Rot A., Sozzani S., Thelen M., Yoshie O., Zlotnik A. (2013) International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. [corrected]. LXXXIX. Update on the extended family of chemokine receptors and introducing a new nomenclature for atypical chemokine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 66, 1–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chee M. S., Satchwell S. C., Preddie E., Weston K. M., Barrell B. G. (1990) Human cytomegalovirus encodes three G protein-coupled receptor homologues. Nature 344, 774–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao J. L., Murphy P. M. (1994) Human cytomegalovirus open reading frame US28 encodes a functional beta chemokine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 28539–28542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicholas J., Cameron K. R., Honess R. W. (1992) Herpesvirus saimiri encodes homologues of G protein-coupled receptors and cyclins. Nature 355, 362–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahuja S. K., Murphy P. M. (1993) Molecular piracy of mammalian interleukin-8 receptor type B by herpesvirus saimiri. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 20691–20694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alcami A., Lira S. A. (2010) Modulation of chemokine activity by viruses. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 22, 482–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahalingam S., Karupiah G. (2000) Modulation of chemokines by poxvirus infections. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12, 409–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lüttichau H. R., Stine J., Boesen T. P., Johnsen A. H., Chantry D., Gerstoft J., Schwartz T. W. (2000) A highly selective CC chemokine receptor (CCR)8 antagonist encoded by the poxvirus molluscum contagiosum. J. Exp. Med. 191, 171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Najarro P., Gubser C., Hollinshead M., Fox J., Pease J., Smith G. L. (2006) Yaba-like disease virus chemokine receptor 7L, a CCR8 orthologue. J. Gen. Virol. 87, 809–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vischer H. F., Leurs R., Smit M. J. (2006) HCMV-encoded G-protein-coupled receptors as constitutively active modulators of cellular signaling networks. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulsen S. J., Rosenkilde M. M., Eugen-Olsen J., Kledal T. N. (2005) Epstein-Barr virus-encoded BILF1 is a constitutively active G protein-coupled receptor. J. Virol. 79, 536–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vischer H. F., Siderius M., Leurs R., Smit M. J. (2014) Herpesvirus-encoded GPCRs: neglected players in inflammatory and proliferative diseases? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 123–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vischer H. F., Vink C., Smit M. J. (2006) A viral conspiracy: hijacking the chemokine system through virally encoded pirated chemokine receptors. In Chemokines and Viral Infection (Lane T. E., ed.), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, 121–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Munnik S. M., Smit M. J., Leurs R., Vischer H. F. (2015) Modulation of cellular signaling by herpesvirus-encoded G protein-coupled receptors. Front. Pharmacol. 6, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britt W. (2008) Manifestations of human cytomegalovirus infection: proposed mechanisms of acute and chronic disease. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 325, 417–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plachter B. (2016) Prospects of a vaccine for the prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus disease. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. (Berl.) 205, 537–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boppana S. B., Ross S. A., Shimamura M., Palmer A. L., Ahmed A., Michaels M. G., Sánchez P. J., Bernstein D. I., Tolan R. W. Jr., Novak Z., Chowdhury N., Britt W. J., Fowler K. B.; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders CHIMES Study (2011) Saliva polymerase-chain-reaction assay for cytomegalovirus screening in newborns. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2111–2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streblow D. N., Orloff S. L., Nelson J. A. (2007) Acceleration of allograft failure by cytomegalovirus. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 19, 577–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sijmons S., Thys K., Mbong Ngwese M., Van Damme E., Dvorak J., Van Loock M., Li G., Tachezy R., Busson L., Aerssens J., Van Ranst M., Maes P. (2015) High-throughput analysis of human cytomegalovirus genome diversity highlights the widespread occurrence of gene-disrupting mutations and pervasive recombination. J. Virol. 89, 7673.–.https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00578-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandler S. H., Handsfield H. H., McDougall J. K. (1987) Isolation of multiple strains of cytomegalovirus from women attending a clinic for sexually transmitted disease. J. Infect. Dis. 155, 655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Görzer I., Kerschner H., Redlberger-Fritz M., Puchhammer-Stöckl E. (2010) Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) genotype populations in immunocompetent individuals during primary HCMV infection. J. Clin. Virol. 48, 100–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faure-Della Corte M., Samot J., Garrigue I., Magnin N., Reigadas S., Couzi L., Dromer C., Velly J.-F., Déchanet-Merville J., Fleury H. J., Lafon M.-E. (2010) Variability and recombination of clinical human cytomegalovirus strains from transplantation recipients. J. Clin. Virol. 47, 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puchhammer-Stöckl E., Görzer I. (2011) Human cytomegalovirus: an enormous variety of strains and their possible clinical significance in the human host. Future Virol. 6, 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dolan A., Cunningham C., Hector R. D., Hassan-Walker A. F., Lee L., Addison C., Dargan D. J., McGeoch D. J., Gatherer D., Emery V. C., Griffiths P. D., Sinzger C., McSharry B. P., Wilkinson G. W. G., Davison A. J. (2004) Genetic content of wild-type human cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 85, 1301–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He R., Ruan Q., Qi Y., Ma Y.-P., Huang Y.-J., Sun Z.-R., Ji Y.-H. (2006) Sequence variability of human cytomegalovirus UL146 and UL147 genes in low-passage clinical isolates. Intervirology 49, 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lurain N. S., Fox A. M., Lichy H. M., Bhorade S. M., Ware C. F., Huang D. D., Kwan S.-P., Garrity E. R., Chou S. (2006) Analysis of the human cytomegalovirus genomic region from UL146 through UL147A reveals sequence hypervariability, genotypic stability, and overlapping transcripts. Virol. J. 3, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baldanti F., Paolucci S., Campanini G., Sarasini A., Percivalle E., Revello M. G., Gerna G. (2006) Human cytomegalovirus UL131A, UL130 and UL128 genes are highly conserved among field isolates. Arch. Virol. 151, 1225–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dargan D. J., Douglas E., Cunningham C., Jamieson F., Stanton R. J., Baluchova K., McSharry B. P., Tomasec P., Emery V. C., Percivalle E., Sarasini A., Gerna G., Wilkinson G. W. G., Davison A. J. (2010) Sequential mutations associated with adaptation of human cytomegalovirus to growth in cell culture. J. Gen. Virol. 91, 1535–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Straschewski S., Patrone M., Walther P., Gallina A., Mertens T., Frascaroli G. (2011) Protein pUL128 of human cytomegalovirus is necessary for monocyte infection and blocking of migration. J. Virol. 85, 5150–5158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao H., Tao R., Zheng Q., Xu J., Shang S. (2013) Recombinant HCMV UL128 expression and functional identification of PBMC-attracting activity in vitro. Arch. Virol. 158, 173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loetscher P., Clark-Lewis I. (2001) Agonistic and antagonistic activities of chemokines. J. Leukoc. Biol. 69, 881–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerna G., Percivalle E., Lilleri D., Lozza L., Fornara C., Hahn G., Baldanti F., Revello M. G. (2005) Dendritic-cell infection by human cytomegalovirus is restricted to strains carrying functional UL131-128 genes and mediates efficient viral antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells. J. Gen. Virol. 86, 275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryckman B. J., Chase M. C., Johnson D. C. (2008) HCMV gH/gL/UL128-131 interferes with virus entry into epithelial cells: evidence for cell type-specific receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 14118–14123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nogalski M. T., Chan G. C., Stevenson E. V., Collins-McMillen D. K., Yurochko A. D. (2013) The HCMV gH/gL/UL128-131 complex triggers the specific cellular activation required for efficient viral internalization into target monocytes. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hahn G., Revello M. G., Patrone M., Percivalle E., Campanini G., Sarasini A., Wagner M., Gallina A., Milanesi G., Koszinowski U., Baldanti F., Gerna G. (2004) Human cytomegalovirus UL131-128 genes are indispensable for virus growth in endothelial cells and virus transfer to leukocytes. J. Virol. 78, 10023–10033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang D., Shenk T. (2005) Human cytomegalovirus virion protein complex required for epithelial and endothelial cell tropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 18153–18158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ciferri C., Chandramouli S., Donnarumma D., Nikitin P. A., Cianfrocco M. A., Gerrein R., Feire A. L., Barnett S. W., Lilja A. E., Rappuoli R., Norais N., Settembre E. C., Carfi A. (2015) Structural and biochemical studies of HCMV gH/gL/gO and pentamer reveal mutually exclusive cell entry complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 1767–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loughney J. W., Rustandi R. R., Wang D., Troutman M. C., Dick L. W. Jr, Li G., Liu Z., Li F., Freed D. C., Price C. E., Hoang V. M., Culp T. D., DePhillips P. A., Fu T.-M., Ha S. (2015) Soluble human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/pUL128-131 pentameric complex, but not gH/gL, inhibits viral entry to epithelial cells and presents dominant native neutralizing epitopes. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 15985–15995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryckman B. J., Rainish B. L., Chase M. C., Borton J. A., Nelson J. A., Jarvis M. A., Johnson D. C. (2008) Characterization of the human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/UL128-131 complex that mediates entry into epithelial and endothelial cells. J. Virol. 82, 60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]