Abstract

A large proportion of cardiovascular (CV) pathology results from immune-mediated damage, including systemic inflammation and cellular proliferation, which cause a narrowing of the blood vessels. Expansions of cytotoxic CD4+ T cells characterized by loss of CD28 (“CD4+CD28− T cells” or “CD4+CD28null cells”) are closely associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD), in particular coronary artery damage. Direct involvement of these cells in damaging the vasculature has been demonstrated repeatedly. Moreover, CD4+CD28− T cells are significantly increased in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other autoimmune conditions. It is striking that expansions of this subset beyond 1–2% occur exclusively in CMV-infected people. CMV infection itself is known to increase the severity of autoimmune diseases, in particular RA and has also been linked to increased vascular pathology. A review of the recent literature on immunological changes in CVD, RA, and CMV infection provides strong evidence that expansions of cytotoxic CD4+CD28− T cells in RA and other chronic inflammatory conditions are limited to CMV-infected patients and driven by CMV infection. They are likely to be responsible for the excess CV mortality observed in these situations. The CD4+CD28− phenotype convincingly links CMV infection to CV mortality based on a direct cellular-pathological mechanism rather than epidemiological association.

Keywords: CD4 T cells, cytotoxic T cells, cardiovascular diseases, chronic inflammatory disease, autoimmune diseases

Introduction

CD28 is a costimulatory molecule expressed on naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. A permanent loss of CD28 occurs during antigen-driven differentiation toward a terminal phenotype. Its loss suggests that costimulation by antigen-presenting cells (APC) via its specific ligands B7.1 (CD80) and B7.2 (CD86) is no longer required and is indicative of replicative senescence (1). This should not be confused with the transient loss of CD28 expression on CD4+ (and CD8+) T cells during proliferation, which is reversible within days (1).

CD4+CD28− T cells were first identified in the plaques of patients with unstable angina but since then, expansions of these cells have been reported in a range of cardiovascular (CV) conditions. They attracted particular interest in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and myocardial infarction where their presence was associated with increased acute mortality and recurrence (2–4). Patients with CD4+CD28− T cell expansions also showed preclinical atherosclerotic changes (5). A recent study of ACS with/without diabetes mellitus (DM) reported the highest frequencies of CD4+CD28− T cells when both conditions were present, followed by ACS only, DM only, and finally controls (6).

As regards autoimmune diseases, expansions of so-called “CD4+CD28null” (synonymous for CD4+CD28−) were described in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients almost 20 years ago (7). Their limited TCR Vβ chain usage suggested restricted antigen-specificity and potential involvement in autoimmunity; interestingly, their numbers were related to the extent of extra-articular involvement (7–9). Over the years, CD4+CD28− T cells have been shown to be implicated in various inflammatory conditions (10) including granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), where CD4+CD28− T cells were linked to increased infection and mortality (11). Table 1 provides a list of conditions in which a role of CD4+CD28− T cells was reported or investigated.

Table 1.

Conditions in which CD4+CD28− T cells were reported and/or investigated.

| Cardiovascular (2, 3, 5, 12–17) | Autoimmune (5, 6, 9, 11, 18–25) | Others (26) |

|---|---|---|

| Angina pectoris | Rheumatoid arthritis | Renal transplant dysfunction |

| Acute coronary syndrome | Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | |

| Myocardial infarction | Diabetes | |

| Chronic heart failure | Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysms | Multiple sclerosis | |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | ||

| Crohn’s disease | ||

| Graves’ disease | ||

| Autoimmune myopathy | ||

| Dermatomyositis | ||

| Polymyositis | ||

| Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis |

CMV Infection Triggers the Expansion of CD4+CD28− T Cells

There is a striking link between CD4+CD28− T cells and CMV infection. Work in renal transplantation has demonstrated that the emergence and expansion of CD4+CD28− T cells in CMV-seronegative (CMV−) graft recipients directly results from infection by a CMV-seropositive (CMV+) graft. Recipients showed detectable levels of CD4+CD28− T cells just after the clearance of CMV viral load, and the proliferation of these cells in vitro could be stimulated by CMV antigen but not tuberculin or tetanus toxoid, for example. However, CD4+CD28− T cells did not emerge in CMV− recipients of CMV− grafts (27). Furthermore, CMV-specific CD4+ T cells are in large part CD28− (28). Given that ex vivo T cell stimulation cannot adequately cover all CMV antigens, it has remained unclear if all CD4+CD28− T cells are CMV-specific or if some of them expand after CMV infection for reasons yet to be discovered. Interestingly, Zal et al. reported that in patients with ACS and/or chronic stable angina CD4+CD28− T cells (partially) responded to HSP60 but not to a CMV lysate (29). It is important to note, however, that CMV lysates (prepared from lytically CMV-infected human fibroblasts) are not an all-inclusive collection of CMV antigens (30). It is possible, therefore, that CD4+CD28− T cells specific for antigens not represented in the lysate cross-reacted with HSP60. Cross-reactivity between HSP60 and the CMV UL122 and US28 proteins has indeed been described for antibodies, which might be an indirect mechanism by which CMV infection facilitates endothelial cell injury (31).

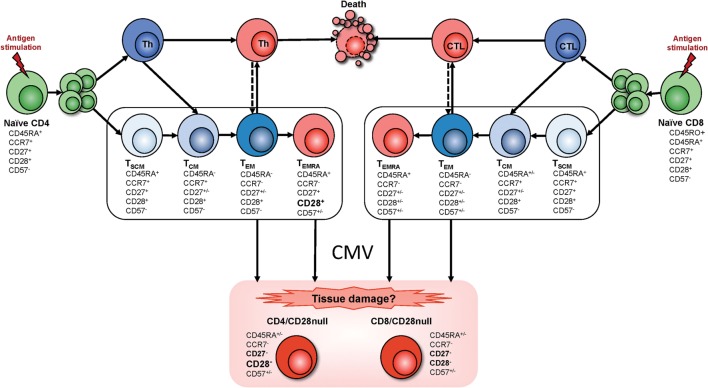

Strikingly, not a single study has reported accumulations of CD4+CD28− T cells in CMV-uninfected individuals; however, some studies have reported low frequencies of these cells in CMV− people in the order of 1–2% of CD4 T cells (11). Of note, in the context of inflammatory diseases such as RA and GPA, CMV-driven expansions of CD4+CD28− T cells are accentuated compared to otherwise healthy individuals, which will increase the potential for tissue damage (11, 32). Based on the literature, we have drafted a model of CMV antigen-driven T cell differentiation toward the emergence of CD4+CD28− T cells (Figure 1). This pathway is different from pathways leading to T cell exhaustion, which are typically associated with a loss of effector functions (33).

Figure 1.

T cell differentiation and the emergence of CMV-induced T cell phenotypes. Memory T cell differentiation is regulated by intracellular and extracellular factors. Mechanisms of memory development upon naïve T cell activation (antigen stimulation) are the subject of ongoing discussion. Since it has been reported that CD4+ T cell memory development resembles that of CD8+ T cells (34), we assumed that both T cell subsets follow similar pathways. However, transitional memory subsets sitting between central memory T cells (TCM) and effector memory T cells (TEM) have been described in the CD4+ T cell compartment. Several memory T cell subsets have been defined but their lineage relationship has remained unclear. Some models describe a linear origin of memory T cells directly from effector T cells; other models propose a divergent differentiation where naïve T cells give rise to memory and effector T cells through asymmetrical division. More recently a progressive differentiation pathway has been proposed, depending on stimulus intensity and duration (represented inside the box). According to this model, T cell fate depends on the duration of signaling and presence/absence of cytokines. Brief stimulation leads to the generation of TCM whereas sustained stimulation plus presence of cytokines generates TEM. Therefore, in the progressive model, a single naïve T cell will give rise to different memory T cell subsets that are the precursors of terminally differentiated effector T cells. Progression into these differentiated memory subsets relies on the gradual response to cytokines, acquisition of tissue homing receptors, resistance to apoptosis, and gain of effector functions while gradually losing lymph node homing receptors, proliferative capacity, and the ability to produce IL-2 production, to self-renew, and survive [for review, see Ref. (35–39)]. Although the exact origin of the CD28− T cell phenotype is not clear, based on the literature, we hypothesize that these cells arise from terminally differentiated effector memory T cells (TEMRA) as well as TEM after exposure to CMV. Abbreviations: Th, T-helper cell; CTL, cytotoxic T cell; TSCM, stem cell memory T cell; TCM, central memory T cell; TEM, effector memory T cell; TEMRA, terminally differentiated (CD45RA reexpressing) effector memory T cell.

CD4+CD28− T Cells are Terminally Differentiated Effector Cells

Before CD4+ T cells lose CD28 expression, they will have lost the expression of a number of other molecules, in particular the costimulatory receptor, CD27, and gained expression of memory markers (40). Unlike normal helper T cells, CD4+CD28− T cells do not provide help to B cells; however, they express NK-cell receptors, in particular killer activating receptors (18, 19, 23). They produce more TNF-α and IFN-γ and are more cytotoxic than CD4+CD28+ T cells (17, 41). CD4+CD28− T cells may home to atheromatous lesions because they express the chemokine receptors, CXCR3, CCR6, and CCR7 (17, 24). Of note, vascular EC are primary CMV infection targets (42). Synovial fluid CD4+CD28− T cells from RA patients produce less IFN-γ and TNF-α than their circulating counterparts and, unlike them, also produce IL-17A (24). Additionally, they produce perforin and granzyme B, which can destroy synovial tissue (41, 43, 44). Reduced responsiveness to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and resistance to apoptosis further add to their destructive potential (22, 45). Table 2 lists the most prominent features of CD4+CD28− T cells.

Table 2.

Properties of CD4+CD28− T cells.

| Molecule type/property | Specific molecules/properties identified (25, 46, 47) |

|---|---|

| Costimulatory receptors | CD27−, CD40L-, OX40+ (CD134), 4-1BB+ (CD137) |

| Chemokine receptors | CCR7−, CX3CR1+ (fractalkine receptor), CCR5+ |

| Toll-like receptors | TLR2+, TLR4+ |

| Natural killer receptors | KIR+, NKG2D+, CD11b+, CD161+, NKG2C+ |

| Cadherin/integrin | VLA-4+, ICAM-1+ |

| Cytokines and mediators | IFN-γ+, TNF-α+, IL-2+, perforin+, granzyme B+ |

| Other features |

|

CMV Involvement in Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)—Clinical Observations and Epidemiology

CMV infection has been associated with vascular pathology ever since the virus was isolated from atherosclerotic lesions, but it was unclear if it played a causative role (48). To date, there is strong epidemiologic evidence that CMV is the major driver of premature CVD in HIV-infected people (49) and increasing recognition of an association with higher CVD mortality in HIV-uninfected people (50). Meanwhile, a role for CMV in driving/accelerating autoimmune disease has been the subject of discussion since the early 1990s (51). Of particular interest to this review, several authors have shown that CMV infection exacerbates inflammation in RA (11, 52–54), with one study indicating that higher anti-CMV antibody levels associate with more frequent surgical procedures and more severe joint damage (53). Several authors have shown that in RA patients CMV antigens are indeed detectable in synovial tissue (55, 56). Also, high numbers of virus-specific T cells including CMV-specific T cells can be found at these sites (52). Table 3 shows CV and autoimmune conditions in which CMV has been implicated.

Table 3.

Cardiovascular and autoimmune conditions in which a role of CMV infection has been suspected or confirmed.

There are several epidemiological links between CMV infection and CVD. In particular, lower socioeconomic position (SEP) correlates with a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia, higher cholesterol, and smoking, which are all risk factors for CVD. However, lower SEP is also associated with a high prevalence of CMV infection (63). Therefore, CVD and CMV are significantly correlated at an epidemiological level in such populations, which complicates the analysis. A recent cross sectional study, however, found that despite this complex interrelatedness of risk factors, CMV infection may explain partly the relationship between SEP and CVD (64). There is also epidemiological evidence that CMV is a driver of heart disease in HIV+ women (65). The complexity and importance of this issue was recently highlighted (49).

Evidence Linking (CMV-Specific) T Cells to Hypertension, Vascular Pathology, and Acute Coronary Events

The evidence for a role of T cells in myocardial infarction has recently been reviewed identifying direct involvement of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in both coronary artery injury and healing/remodeling with regulatory T cells being particularly involved in the latter (66).

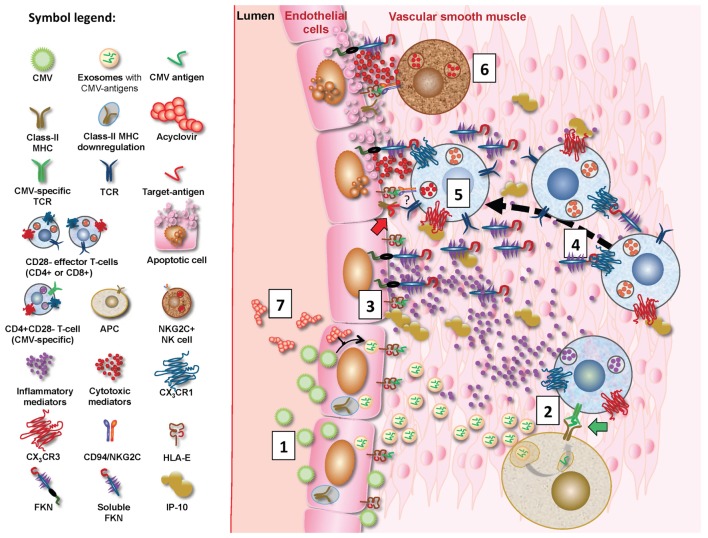

Following CMV infection of EC, class-II MHC expression in these cells is reduced hampering CMV-antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells (67). However, CMV-infected EC can release non-infectious exosomes (NIE) that are replete with CMV proteins, in particular UL55, a major CD4+ T cell target protein. Uptake of NIE by APC leads to effective presentation of CMV antigens to CD4+ T cells (68). Moreover, pro-inflammatory mediators released by PBMCs in response to CMV can induce expression of fractalkine (FKN) and inducible protein 10 (IP-10) in EC. These specifically bind the chemokine receptors CX3CR1 and CX3CR3, respectively, which are expressed on effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in CMV-infected individuals (69). We hypothesize that vasculature-infiltrating CD4+CD28− effector T cells expressing CX3CR1 and/or CX3CR3 are, therefore, attracted to FKN and IP-10-producing EC. Cytotoxic molecules secreted by CD28− T cells (Table 2) may then trigger EC death by apoptosis. Of interest, CMV immune evasion includes downregulation of class-I MHC expression on infected EC but leaves HLA-E expression unaffected. NKG2C+-expressing NK cells and T cells expand in CMV infection, and NKG2C+-mediated cytotoxicity is triggered by the interaction between CD94/NKG2C and HLA-E molecules on CMV-infected EC (70, 71). Figure 2 provides a synopsis of these mechanisms.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanisms for CMV-driven vascular damage. CMV-infected EC will downregulate MHC expression but produce non-infectious exosomes (NIE) loaded with CMV proteins, in particular UL55 (gB) (1) (68), allowing effective CMV antigen presentation by antigen-presenting cells (APC) following NIE uptake/processing. Vasculature-infiltrating CMV-specific CD4+ effector T cells will hence encounter these antigens on APC (shown as green CMV antigen in diagram; green block arrow) (2) and subsequently produce pro-inflammatory mediators such as IFN-γ. These induce the expression of fractalkine (FKN), IFN-γ-inducible protein 10, and possibly additional chemokines in EC (3) (69), which in turn attract infiltrating CD4+CD28− and probably also CD8+CD28− T cells to the ECs (4). These may be CMV-specific but possibly also non-CMV-specific (symbolized by red “target antigen” in diagram; red block arrow). They may kill ECs through perforin/granzyme secretion (5). Despite CMV infection, HLA-E expression remains unaffected in EC, so that interaction between HLA-E on EC and CD94/NKG2C on NK cells may also trigger CD94/NKG2C-mediated cytotoxicity (6) (71). NKG2C+ NK cells are known to be expanded by CMV infection and it is noteworthy that CD4+CD28− T cells may also express NKG2C (indicated by “?” in diagram). Acyclovir reduces CMV-specific T cell responses by inhibiting replication (72) and will probably reduce NIE formation in infected EC, thus reducing antigen presentation by APCs and subsequent effector T cell activation (7).

Work in mouse models has also confirmed a role for T cells in hypertension, an important contributor to vascular damage; RAG-1 double-knockout (RAG-1−/−) mice lacking both T cells and B-cells showed blunted hypertension in response to angiotensin-II infusion or (DOCA)-salt. They also exhibited decreased vascular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production with reduced consumption of the relaxing factor, nitric oxide (NO). Adoptive transfer of T cells (but not B-cells) restored these effects to normal (73). Others showed that murine CMV (MCMV) infection leads to hypertension within weeks independently of atherosclerotic plaque formation, but at the same time contributes to (aortic) atherosclerosis, which might result from persistent CMV infection of EC inducing renin expression (74). This will in turn increase local angiotensin-II levels, which might activate angiotensin-II receptor positive infiltrating T cells to produce more ROS. Recently, Pachnio et al (75). have confirmed that CMV-induced CD4+CD28− T cells indeed have all the necessary properties required to infiltrate the vasculature.

RA and CV Complications

As a result of an excess of CV events, the life expectancy of RA patients is reduced by 3–10 years compared with the general population (76, 77). The risk of CVD-associated death is up to 50% higher in RA patients than controls, and the risks of ischemic heart and cerebrovascular diseases are elevated to a similar extent (78). RA is the most common inflammatory joint disease worldwide, affecting about 1% of the population (77). RA is characterized by infiltration of the synovial membranes by pro-inflammatory immune cells, swelling and deformity of joints and excess synovial fluid containing infiltrating immune cells and cytokines (79, 80). Extra-articular manifestations are widespread and involve the CV system (81).

Traditional CVD risk factors such as smoking, physical inactivity, hypertension, and DM contribute to death from CVD in RA but do not have the same predictive value as in patients without RA (77, 82). There is some evidence that RA itself accelerates atherogenesis (83). Also, following myocardial infarction patients with RA have considerably higher 30-day case fatality rates (76). Chronic inflammation is a normal consequence of aging (84) and a key player in atherogenesis. It promotes endothelial cell activation and vascular dysfunction and, together with other risk factors, leads to arterial wall thickening, promotes atheromatous changes, induces decreased vascular compliance, and contributes to increased blood pressure. This further promotes vascular damage in a self-perpetuating cycle. Ultimately, blockage of blood vessels may lead to myocardial infarction or stroke (76, 85).

CD4+CD28− T Cells Arise as an Obvious Mechanistic Link Between CMV Infection, CVD, and RA

The vast majority of studies investigating the presence and role of CD4+CD28− T cells in CVD and autoimmune diseases did so without considering participant CMV infection status, suggesting that many researchers are unaware of the association of an expansion of this subset with CMV infection. The most relevant details from a number of such reports are found in Tables S1 and S2 in Supplementary Material. Only a handful of studies explored the presence of CD4+CD28− and/or CD8+CD28− T cells in CVD or autoimmune disease in the context of CMV infection status. Interestingly, most of these included CMV+participants only. We identified only two studies that included CMV+ and CMV− participants (Table 4). Among the studies not accounting for CMV status, several reported significant differences between RA patients and healthy controls with respect to the frequency of CD4+CD28− T cells (5, 8, 20, 32). Also, major differences were reported between cases with limited RA and extra-articular RA (21). On the whole, between 3 and 10 times, more CD4+CD28− T cells were reported in RA compared to healthy controls. With respect to CVD, Liuzzo et al. found ninefold higher levels of CD4+CD28− T cells in patients with unstable angina compared to those with stable angina; these differences were later confirmed in a second study (2, 3). Rizzello et al., by contrast, found “only” a 2.5-fold difference in CD4+CD28− T cell levels between such groups (13). Others reported frequencies of CD4+CD28− lymphocytes (rather than T cells) as a percentage of all lymphocytes, which makes their data difficult to compare (17).

Table 4.

CD4+CD28− T cells in studies stratified by CMV status.

| Reference | Disease | Number of individuals in study | M:F ratio | Age range or IQR in years (median) and/or mean ± SD | Cell subset investigated | % of reference subset given as mean or median or absolute counts/µl blood mean ± SD |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMV+ | CMV– | ||||||

| Thewissen et al. (22) | Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | 4 | 1:3 | 59–76 (67) | CD4+CD28− | 9.6 | n.k. |

| HC | 4 | 3:1 | 30–48 (35) | 9.3 | n.k. | ||

| Morgan et al. (11) | GPAa | 48 | 25:23 | 47–74 (64) | CD4+CD28− | 19 | 0.8 |

| HC | 38 | 13:25 | 41–77 (57) | 22 | 1.4 | ||

| Pierer et al. (53) | RA | 202 | 49:153 | 51–68 (62) | CD4+CD28− | 8.15 | 0.37 |

| Jonasson et al. (86) | Cardiovascular disease | 43b | All males | 55.1 ± 5.6 | CD4+CD28− | 6.7 | |

| CD8+CD28− | 452 ± 258 | 172 ± 174 | |||||

| CD8+CD57+ | 392 ± 226 | 167 ± 183 | |||||

| HC | 69b | All males | 49.5 ± 5.9 | CD4+CD28− | 5.8 | ||

| CD8+CD28− | 329 ± 216 | 112 ± 71 | |||||

| CD8+CD57+ | 269 ± 190 | 105 ± 67 | |||||

n.k., not known; HC, healthy control.

aGPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, was used here as a comparative inflammatory disorder.

b67% of patients and 61% of controls were CMV+.

Significance of Italics: % of reference subset given as median, as indicated in the headings of the columns.

Reports in GPA and RA patients clearly confirm that significant expansions of the CD4+CD28− T cell subset only occur in CMV+ individuals. The levels of these cells were 24-fold higher and 22-fold higher in CMV+ compared with CMV− GPA and RA patients, respectively (11, 53). Also, the relative expansions in CMV+ compared to CMV− individuals were significantly accelerated in the presence of GPA as they were increased “only” by factor 14 higher in healthy controls. The remaining studies listed in Table 4 report CD4+CD28− T cell frequencies in CMV+ individuals only.

In summary, the listed reports argue strongly in favor of a role of CMV infection in CV complications, most likely as a result of the distribution of the CD4+CD28− subsets in the disease and control groups.

Could CD4+CD28− T Cells be Targeted by Immunotherapies?

Experimental evidence suggests that anti-CMV treatment could reduce the reactivity as well as the numbers of CMV-specific T cells. Particularly, low dose acyclovir therapy decreases the CD4+ T cell response to pp65 CMV protein, most likely by diminishing the CMV-antigen load, turnover, and uptake by APC (72). In addition, there is evidence from mouse models that, at least in older mice, valacyclovir treatment leads to an 80% reduction of the CD8+ T cell response to MCMV (87). If CMV-specific T cells were actually involved in mediating CMV-driven vascular damage, then a possible approach to slow down this process would be the use of anti-viral drugs.

Therapies based on the direct targeting of CD4+CD28− T cells have been investigated in several conditions. To this regard, the effects of different therapeutic regimens on CD4+CD28− T cell frequencies have been investigated in patients with hyperinsulinemic polycystic ovary syndrome, in which increased frequencies of this subset have also been observed (but an association with CMV has not been investigated). Treatment with drospirenone–ethinylestradiol and metformin resulted in a significant reduction of frequencies of CD4+CD28− T cells (88). Moreover, it has been demonstrated in organ transplant recipients that treatment with polyclonal anti-thymocyte globulin preferentially triggers apoptosis in CD4+CD28− compared to CD4+CD28+ T cells (89). Other therapies targeting the functional capacity of these cytotoxic cells have been investigated as well. The only K+ channels present in CD4+CD28− T cells from ACS patients are Kv1.3 and IKCa1. Blockade of the Kv1.3 channel by 5-(4-phenoxybutoxy)psoralen (PAP-1) resulted in suppression of the pro-inflammatory function of CD4+CD28− T cells (90), however, did not appear to induce general immunosuppression. In a rat model, chronic administration of PAP-1 prevented the development of unstable atherosclerotic plaques, most probably by blocking the release of inflammatory and cytotoxic molecules from CD4+CD28− T cells (91). Finally, in RA patients treated with abatacept, a reduction of circulating CD4+CD28− T cells has been observed, and it was correlated with a reduction of disease activity (92–94). Similar results were observed by Pierer et al. (95) in RA patients treated with TNF-α blocking agents (etanercept and infliximab). Anti-TNF therapy has been shown to diminish the myocardial infarction risk and to increase vascular compliance (96, 97). At the same time, it reduces the number of CD4+CD28− T cells (13). However, little is known about how other drugs used in RA affect CV complications (recently reviewed in this journal) (98).

Conclusion

We believe that the literature reviewed in this article explains to a large extent the striking epidemiological association reported between CMV infection and increased CV mortality (50, 60, 99–102). It is, in particular, the emerging, immediate and specific role of CD4+CD28− T cells in both acute and chronic vascular pathology that takes this association to a higher level. This is, because expansion of this T cell subset beyond a very small percentage (1–2% of CD4+ T cells) is exclusively found in CMV+ individuals. Literature from the fields of chronic inflammation/autoimmunity, CVD, and viral immunology, together provide a fascinating insight into the effects of expanded populations of cytotoxic, CD4+CD28− T cells. These are ultimately driven by a common virus infection, whose burden on the immune system is still being underestimated (103).

Author Contributions

IB: literature search, review, compilation of supplementary tables including all relevant information, and initial draft. AP: literature search, review, revising, and rewriting draft, figures’ design and drawing, and writing/editing final manuscript. GM: literature review and contributions to writing and editing final manuscript. KD: contributions to writing manuscript, editing, and contribution to tables and figures. FK: initiation of the work, literature review and selection, contributing to tables and figures, critical review of all information, and writing of the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This review article has no specific funder; it was funded indirectly by BSMS as an employer of the authors, AP, KD, and FK. IB was at the time of writing a final year student as the University of Sussex undertaking a final year project at BSMS.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00195/full#supplementary-material.

References

- 1.Vallejo AN, Brandes JC, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Modulation of CD28 expression: distinct regulatory pathways during activation and replicative senescence. J Immunol (1999) 162(11):6572–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liuzzo G, Kopecky SL, Frye RL, O’Fallon WM, Maseri A, Goronzy JJ, et al. Perturbation of the T-cell repertoire in patients with unstable angina. Circulation (1999) 100(21):2135–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liuzzo G, Goronzy JJ, Yang H, Kopecky SL, Holmes DR, Frye RL, et al. Monoclonal T-cell proliferation and plaque instability in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation (2000) 101(25):2883–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.25.2883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liuzzo G, Biasucci LM, Trotta G, Brugaletta S, Pinnelli M, Digianuario G, et al. Unusual CD4+CD28null T lymphocytes and recurrence of acute coronary events. J Am Coll Cardiol (2007) 50(15):1450–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerli R, Schillaci G, Giordano A, Bocci EB, Bistoni O, Vaudo G, et al. CD4+CD28- T lymphocytes contribute to early atherosclerotic damage in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Circulation (2004) 109(22):2744–8. 10.1161/01.cir.0000131450.66017.b3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giubilato S, Liuzzo G, Brugaletta S, Pitocco D, Graziani F, Smaldone C, et al. Expansion of CD4+CD28null T-lymphocytes in diabetic patients: exploring new pathogenetic mechanisms of increased cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus. Eur Heart J (2011) 32(10):1214–26. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martens PB, Goronzy JJ, Schaid D, Weyand CM. Expansion of unusual CD4+ T cells in severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum (1997) 40(6):1106–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt D, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. CD4+ CD7- CD28- T cells are expanded in rheumatoid arthritis and are characterized by autoreactivity. J Clin Invest (1996) 97(9):2027–37. 10.1172/jci118638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt D, Martens PB, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. The repertoire of CD4+ CD28- T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Med (1996) 2(5):608–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumitriu IE. The life (and death) of CD4+ CD28(null) T cells in inflammatory diseases. Immunology (2015) 146(2):185–93. 10.1111/imm.12506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan MD, Pachnio A, Begum J, Roberts D, Rasmussen N, Neil DA, et al. CD4+CD28- T cell expansion in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) is driven by latent cytomegalovirus infection and is associated with an increased risk of infection and mortality. Arthritis Rheum (2011) 63(7):2127–37. 10.1002/art.30366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brugaletta S, Biasucci LM, Pinnelli M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Di Giannuario G, Trotta G, et al. Novel anti-inflammatory effect of statins: reduction of CD4+CD28null T lymphocyte frequency in patients with unstable angina. Heart (2006) 92(2):249–50. 10.1136/hrt.2004.052282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizzello V, Liuzzo G, Brugaletta S, Rebuzzi A, Biasucci LM, Crea F. Modulation of CD4(+)CD28null T lymphocytes by tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade in patients with unstable angina. Circulation (2006) 113(19):2272–7. 10.1161/circulationaha.105.588533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alber HF, Duftner C, Wanitschek M, Dorler J, Schirmer M, Suessenbacher A, et al. Neopterin, CD4+CD28- lymphocytes and the extent and severity of coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol (2009) 135(1):27–35. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumitriu IE, Araguas ET, Baboonian C, Kaski JC. CD4+ CD28 null T cells in coronary artery disease: when helpers become killers. Cardiovasc Res (2009) 81(1):11–9. 10.1093/cvr/cvn248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koller L, Richter B, Goliasch G, Blum S, Korpak M, Zorn G, et al. CD4+ CD28(null) cells are an independent predictor of mortality in patients with heart failure. Atherosclerosis (2013) 230(2):414–6. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teo FH, de Oliveira RT, Mamoni RL, Ferreira MC, Nadruz W, Jr, Coelho OR, et al. Characterization of CD4+CD28null T cells in patients with coronary artery disease and individuals with risk factors for atherosclerosis. Cell Immunol (2013) 281(1):11–9. 10.1016/j.cellimm.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Namekawa T, Wagner UG, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Functional subsets of CD4 T cells in rheumatoid synovitis. Arthritis Rheum (1998) 41(12):2108–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Namekawa T, Snyder MR, Yen JH, Goehring BE, Leibson PJ, Weyand CM, et al. Killer cell activating receptors function as costimulatory molecules on CD4+CD28null T cells clonally expanded in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol (2000) 165(2):1138–45. 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryl E, Vallejo AN, Matteson EL, Witkowski JM, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Modulation of CD28 expression with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum (2005) 52(10):2996–3003. 10.1002/art.21353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel JJ, Turesson C, Lemster B, Atkins SR, Iclozan C, Bongartz T, et al. CD56-expressing T cells that have features of senescence are expanded in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum (2007) 56(1):43–57. 10.1002/art.22310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thewissen M, Somers V, Hellings N, Fraussen J, Damoiseaux J, Stinissen P. CD4+CD28null T cells in autoimmune disease: pathogenic features and decreased susceptibility to immunoregulation. J Immunol (2007) 179(10):6514–23. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fasth AE, Bjorkstrom NK, Anthoni M, Malmberg KJ, Malmstrom V. Activating NK-cell receptors co-stimulate CD4(+)CD28(-) T cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol (2010) 40(2):378–87. 10.1002/eji.200939399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pieper J, Johansson S, Snir O, Linton L, Rieck M, Buckner JH, et al. Peripheral and site-specific CD4(+) CD28(null) T cells from rheumatoid arthritis patients show distinct characteristics. Scand J Immunol (2014) 79(2):149–55. 10.1111/sji.12139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maly K, Schirmer M. The story of CD4+ CD28- T cells revisited: solved or still ongoing? J Immunol Res (2015) 2015:348746. 10.1155/2015/348746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shabir S, Smith H, Kaul B, Pachnio A, Jham S, Kuravi S, et al. Cytomegalovirus-associated CD4(+) CD28(null) cells in NKG2D-dependent glomerular endothelial injury and kidney allograft dysfunction. Am J Transplant (2016) 16(4):1113–28. 10.1111/ajt.13614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Leeuwen EM, Remmerswaal EB, Vossen MT, Rowshani AT, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, van Lier RA, et al. Emergence of a CD4+CD28- granzyme B+, cytomegalovirus-specific T cell subset after recovery of primary cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol (2004) 173(3):1834–41. 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akbar AN, Fletcher JM. Memory T cell homeostasis and senescence during aging. Curr Opin Immunol (2005) 17(5):480–5. 10.1016/j.coi.2005.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zal B, Kaski JC, Arno G, Akiyu JP, Xu Q, Cole D, et al. Heat-shock protein 60-reactive CD4+CD28null T cells in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation (2004) 109(10):1230–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118476.29352.2A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB, Taormina C, Pelte C, Ruchti F, et al. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med (2005) 202(5):673–85. 10.1084/jem.20050882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bason C, Corrocher R, Lunardi C, Puccetti P, Olivieri O, Girelli D, et al. Interaction of antibodies against cytomegalovirus with heat-shock protein 60 in pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Lancet (2003) 362(9400):1971–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15016-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thewissen M, Somers V, Venken K, Linsen L, van Paassen P, Geusens P, et al. Analyses of immunosenescent markers in patients with autoimmune disease. Clin Immunol (2007) 123(2):209–18. 10.1016/j.clim.2007.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol (2015) 15(8):486–99. 10.1038/nri3862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrington LE, Janowski KM, Oliver JR, Zajac AJ, Weaver CT. Memory CD4 T cells emerge from effector T-cell progenitors. Nature (2008) 452(7185):356–60. 10.1038/nature06672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaech SM, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Effector and memory T-cell differentiation: implications for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol (2002) 2(4):251–62. 10.1038/nri778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ojdana D, Safiejko K, Lipska A, Radziwon P, Dadan J, Tryniszewska E. Effector and memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the chronic infection process. Folia Histochem Cytobiol (2008) 46(4):413–7. 10.2478/v10042-008-0077-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmed R, Bevan MJ, Reiner SL, Fearon DT. The precursors of memory: models and controversies. Nat Rev Immunol (2009) 9(9):662–8. 10.1038/nri2619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farber DL, Yudanin NA, Restifo NP. Human memory T cells: generation, compartmentalization and homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol (2014) 14(1):24–35. 10.1038/nri3567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flynn JK, Gorry PR. Stem memory T cells (TSCM)-their role in cancer and HIV immunotherapies. Clin Transl Immunol (2014) 3(7):e20. 10.1038/cti.2014.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Appay V, van Lier RA, Sallusto F, Roederer M. Phenotype and function of human T lymphocyte subsets: consensus and issues. Cytometry A (2008) 73(11):975–83. 10.1002/cyto.a.20643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Appay V, Zaunders JJ, Papagno L, Sutton J, Jaramillo A, Waters A, et al. Characterization of CD4(+) CTLs ex vivo. J Immunol (2002) 168(11):5954–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ho DD, Rota TR, Andrews CA, Hirsch MS. Replication of human cytomegalovirus in endothelial cells. J Infect Dis (1984) 150(6):956–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Komocsi A, Lamprecht P, Csernok E, Mueller A, Holl-Ulrich K, Seitzer U, et al. Peripheral blood and granuloma CD4(+)CD28(–) T cells are a major source of interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Am J Pathol (2002) 160(5):1717–24. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61118-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis JM, Knutson KL, Strausbauch MA, Green AB, Crowson CS, Therneau TM, et al. Immune response profiling in early rheumatoid arthritis: discovery of a novel interaction of treatment response with viral immunity. Arthritis Res Ther (2013) 15(6):R199. 10.1186/ar4389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsaknaridis L, Spencer L, Culbertson N, Hicks K, LaTocha D, Chou YK, et al. Functional assay for human CD4+CD25+ Treg cells reveals an age-dependent loss of suppressive activity. J Neurosci Res (2003) 74(2):296–308. 10.1002/jnr.10766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weyand CM, Brandes JC, Schmidt D, Fulbright JW, Goronzy JJ. Functional properties of CD4+ CD28- T cells in the aging immune system. Mech Ageing Dev (1998) 102(2–3):131–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almehmadi M, Hammad A, Heyworth S, Moberly J, Middleton D, Hopkins MJ, et al. CD56+ T cells are increased in kidney transplant patients following cytomegalovirus infection. Transpl Infect Dis (2015) 17(4):518–26. 10.1111/tid.12405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Degre M. Has cytomegalovirus infection any role in the development of atherosclerosis? Clin Microbiol Infect (2002) 8(4):191–5. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2002.00407.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aiello AE, Simanek AM. Cytomegalovirus and immunological aging: the real driver of HIV and heart disease? J Infect Dis (2012) 205(12):1772–4. 10.1093/infdis/jis288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simanek AM, Dowd JB, Pawelec G, Melzer D, Dutta A, Aiello AE. Seropositivity to cytomegalovirus, inflammation, all-cause and cardiovascular disease-related mortality in the United States. PLoS One (2011) 6(2):e16103. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halenius A, Hengel H. Human cytomegalovirus and autoimmune disease. Biomed Res Int (2014) 2014:472978. 10.1155/2014/472978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tan LC, Mowat AG, Fazou C, Rostron T, Roskell H, Dunbar PR, et al. Specificity of T cells in synovial fluid: high frequencies of CD8(+) T cells that are specific for certain viral epitopes. Arthritis Res (2000) 2(2):154–64. 10.1186/ar80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pierer M, Rothe K, Quandt D, Schulz A, Rossol M, Scholz R, et al. Association of anticytomegalovirus seropositivity with more severe joint destruction and more frequent joint surgery in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum (2012) 64(6):1740–9. 10.1002/art.34346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quandt D, Rothe K, Scholz R, Baerwald CW, Wagner U. Peripheral CD4CD8 double positive T cells with a distinct helper cytokine profile are increased in rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One (2014) 9(3):e93293. 10.1371/journal.pone.0093293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Einsele H, Steidle M, Muller CA, Fritz P, Zacher J, Schmidt H, et al. Demonstration of cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA and anti-CMV response in the synovial membrane and serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol (1992) 19(5):677–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murayama T, Jisaki F, Ayata M, Sakamuro D, Hironaka T, Hirai K, et al. Cytomegalovirus genomes demonstrated by polymerase chain reaction in synovial fluid from rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol (1992) 10(2):161–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nieto FJ, Adam E, Sorlie P, Farzadegan H, Melnick JL, Comstock GW, et al. Cohort study of cytomegalovirus infection as a risk factor for carotid intimal-medial thickening, a measure of subclinical atherosclerosis. Circulation (1996) 94(5):922–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Streblow DN, Orloff SL, Nelson JA. The HCMV chemokine receptor US28 is a potential target in vascular disease. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord (2001) 1(2):151–8. 10.2174/1568005014606080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ji YN, An L, Zhan P, Chen XH. Cytomegalovirus infection and coronary heart disease risk: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep (2012) 39(6):6537–46. 10.1007/s11033-012-1482-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tracy RP, Doyle MF, Olson NC, Huber SA, Jenny NS, Sallam R, et al. T-helper type 1 bias in healthy people is associated with cytomegalovirus serology and atherosclerosis: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc (2013) 2(3):e000117. 10.1161/jaha.113.000117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hjelmesaeth J, Sagedal S, Hartmann A, Rollag H, Egeland T, Hagen M, et al. Asymptomatic cytomegalovirus infection is associated with increased risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus and impaired insulin release after renal transplantation. Diabetologia (2004) 47(9):1550–6. 10.1007/s00125-004-1499-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Soderberg-Naucler C. Autoimmunity induced by human cytomegalovirus in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther (2012) 14(1):101. 10.1186/ar3525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dowd JB, Aiello AE, Alley DE. Socioeconomic disparities in the seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the US population: NHANES III. Epidemiol Infect (2009) 137(1):58–65. 10.1017/S0950268808000551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simanek AM, Dowd JB, Aiello AE. Persistent pathogens linking socioeconomic position and cardiovascular disease in the US. Int J Epidemiol (2009) 38(3):775–87. 10.1093/ije/dyn273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parrinello CM, Sinclair E, Landay AL, Lurain N, Sharrett AR, Gange SJ, et al. Cytomegalovirus immunoglobulin G antibody is associated with subclinical carotid artery disease among HIV-infected women. J Infect Dis (2012) 205(12):1788–96. 10.1093/infdis/jis276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hofmann U, Frantz S. Role of T-cells in myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J (2016) 37(11):873–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sedmak DD, Guglielmo AM, Knight DA, Birmingham DJ, Huang EH, Waldman WJ. Cytomegalovirus inhibits major histocompatibility class II expression on infected endothelial cells. Am J Pathol (1994) 144(4):683–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walker JD, Maier CL, Pober JS. Cytomegalovirus-infected human endothelial cells can stimulate allogeneic CD4+ memory T cells by releasing antigenic exosomes. J Immunol (2009) 182(3):1548–59. 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van de Berg PJ, Yong SL, Remmerswaal EB, van Lier RA, ten Berge IJ. Cytomegalovirus-induced effector T cells cause endothelial cell damage. Clin Vaccine Immunol (2012) 19(5):772–9. 10.1128/CVI.00011-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Almehmadi M, Flanagan BF, Khan N, Alomar S, Christmas SE. Increased numbers and functional activity of CD56(+) T cells in healthy cytomegalovirus positive subjects. Immunology (2014) 142(2):258–68. 10.1111/imm.12250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Djaoud Z, Riou R, Gavlovsky PJ, Mehlal S, Bressollette C, Gerard N, et al. Cytomegalovirus-infected primary endothelial cells trigger NKG2C+ natural killer cells. J Innate Immun (2016) 8(4):374–85. 10.1159/000445320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pachnio A, Begum J, Fox A, Moss P. Acyclovir therapy reduces the CD4+ T cell response against the immunodominant pp65 protein from cytomegalovirus in immune competent individuals. PLoS One (2015) 10(4):e0125287. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, et al. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med (2007) 204(10):2449–60. 10.1084/jem.20070657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheng J, Ke Q, Jin Z, Wang H, Kocher O, Morgan JP, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection causes an increase of arterial blood pressure. PLoS Pathog (2009) 5(5):e1000427. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pachnio A, Ciaurriz M, Begum J, Lal N, Zuo J, Beggs A, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection leads to development of high frequencies of cytotoxic virus-specific CD4+ T cells targeted to vascular endothelium. PLoS Pathog (2016) 12(9):e1005832. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaplan MJ. Cardiovascular complications of rheumatoid arthritis: assessment, prevention, and treatment. Rheum Dis Clin North Am (2010) 36(2):405–26. 10.1016/j.rdc.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Amaya-Amaya J, Sarmiento-Monroy JC, Mantilla RD, Pineda-Tamayo R, Rojas-Villarraga A, Anaya JM. Novel risk factors for cardiovascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Res (2013) 56(2–3):267–86. 10.1007/s12026-013-8398-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Avina-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, Etminan M, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum (2008) 59(12):1690–7. 10.1002/art.24092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Libby P. Role of inflammation in atherosclerosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med (2008) 121(10 Suppl 1):S21–31. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Waldele S, Koers-Wunrau C, Beckmann D, Korb-Pap A, Wehmeyer C, Pap T, et al. Deficiency of fibroblast activation protein alpha ameliorates cartilage destruction in inflammatory destructive arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther (2015) 17(1):12. 10.1186/s13075-015-0524-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maradit-Kremers H, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, Ballman KV, Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular death in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum (2005) 52(3):722–32. 10.1002/art.20878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med (2008) 121(10 Suppl 1):S9–14. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.del Rincon ID, Williams K, Stern MP, Freeman GL, Escalante A. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum (2001) 44(12):2737–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Franceschi C, Bonafe M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, et al. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2000) 908(1):244–54. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med (2005) 352(16):1685–95. 10.1056/NEJMra043430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jonasson L, Tompa A, Wikby A. Expansion of peripheral CD8+ T cells in patients with coronary artery disease: relation to cytomegalovirus infection. J Intern Med (2003) 254(5):472–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beswick M, Pachnio A, Lauder SN, Sweet C, Moss PA. Antiviral therapy can reverse the development of immune senescence in elderly mice with latent cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol (2013) 87(2):779–89. 10.1128/JVI.02427-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moro F, Morciano A, Tropea A, Sagnella F, Palla C, Scarinci E, et al. Effects of drospirenone-ethinylestradiol and/or metformin on CD4(+)CD28(null) T lymphocytes frequency in women with hyperinsulinemia having polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Reprod Sci (2013) 20(12):1508–17. 10.1177/1933719113488444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Duftner C, Dejaco C, Hengster P, Bijuklic K, Joannidis M, Margreiter R, et al. Apoptotic effects of antilymphocyte globulins on human pro-inflammatory CD4+CD28- T-cells. PLoS One (2012) 7(3):e33939. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xu R, Cao M, Wu X, Wang X, Ruan L, Quan X, et al. Kv1.3 channels as a potential target for immunomodulation of CD4+ CD28null T cells in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Clin Immunol (2012) 142(2):209–17. 10.1016/j.clim.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu X, Xu R, Cao M, Ruan L, Wang X, Zhang C. Effect of the Kv1.3 voltage-gated potassium channel blocker PAP-1 on the initiation and progress of atherosclerosis in a rat model. Heart Vessels (2015) 30(1):108–14. 10.1007/s00380-013-0462-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Scarsi M, Ziglioli T, Airo P. Baseline numbers of circulating CD28-negative T cells may predict clinical response to abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol (2011) 38(10):2105–11. 10.3899/jrheum.110386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Airo P, Scarsi M. Targeting CD4+CD28- T cells by blocking CD28 co-stimulation. Trends Mol Med (2013) 19(1):1–2. 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Imberti L, Scarsi M, Zanotti C, Chiarini M, Bertoli D, Tincani A, et al. Reduced T-cell repertoire restrictions in abatacept-treated rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Transl Med (2015) 13:12. 10.1186/s12967-014-0363-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pierer M, Rossol M, Kaltenhauser S, Arnold S, Hantzschel H, Baerwald C, et al. Clonal expansions in selected TCR BV families of rheumatoid arthritis patients are reduced by treatment with the TNFalpha inhibitors etanercept and infliximab. Rheumatol Int (2011) 31(8):1023–9. 10.1007/s00296-010-1402-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dixon WG, Watson KD, Lunt M, Hyrich KL, British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register Control Centre Consortium. Silman AJ, et al. Reduction in the incidence of myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who respond to anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Rheum (2007) 56(9):2905–12. 10.1002/art.22809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Barnabe C, Martin BJ, Ghali WA. Systematic review and meta-analysis: anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy and cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) (2011) 63(4):522–9. 10.1002/acr.20371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mason JC, Libby P. Cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic inflammation: mechanisms underlying premature cardiovascular events in rheumatologic conditions. Eur Heart J (2015) 36(8):482c–9c. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Guech-Ongey M, Brenner H, Twardella D, Hahmann H, Rothenbacher D. Role of cytomegalovirus sero-status in the development of secondary cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease under special consideration of diabetes. Int J Cardiol (2006) 111(1):98–103. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang GC, Kao WH, Murakami P, Xue QL, Chiou RB, Detrick B, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection and the risk of mortality and frailty in older women: a prospective observational cohort study. Am J Epidemiol (2010) 171(10):1144–52. 10.1093/aje/kwq062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Savva GM, Pachnio A, Kaul B, Morgan K, Huppert FA, Brayne C, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with increased mortality in the older population. Aging Cell (2013) 12(3):381–7. 10.1111/acel.12059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Spyridopoulos I, Martin-Ruiz C, Hilkens C, Yadegarfar ME, Isaacs J, Jagger C, et al. CMV seropositivity and T-cell senescence predict increased cardiovascular mortality in octogenarians: results from the Newcastle 85+ study. Aging Cell (2015) 15(2):389–92. 10.1111/acel.12430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Manicklal S, Emery VC, Lazzarotto T, Boppana SB, Gupta RK. The “silent” global burden of congenital cytomegalovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev (2013) 26(1):86–102. 10.1128/CMR.00062-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.