Fibroblastic reticular cells influence the function of lymphocytes in secondary lymphoid organs. Ludewig and colleagues demonstrate that they also specifically restrain the activation of group 1 innate lymphoid cells in the presence of microbial stimulation to prevent immunopathology.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/ni.3566) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Subject terms: Innate lymphoid cells, Mucosal immunology, Lymph node

Abstract

Fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) of secondary lymphoid organs form distinct niches for interaction with hematopoietic cells. We found here that production of the cytokine IL-15 by FRCs was essential for the maintenance of group 1 innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) in Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes. Moreover, FRC-specific ablation of the innate immunological sensing adaptor MyD88 unleashed IL-15 production by FRCs during infection with an enteropathogenic virus, which led to hyperactivation of group 1 ILCs and substantially altered the differentiation of helper T cells. Accelerated clearance of virus by group 1 ILCs precipitated severe intestinal inflammatory disease with commensal dysbiosis, loss of intestinal barrier function and diminished resistance to colonization. In sum, FRCs act as an 'on-demand' immunological 'rheostat' by restraining activation of group 1 ILCs and thereby preventing immunopathological damage in the intestine.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/ni.3566) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Main

The intestine harbors a vast number of commensal microorganisms and is frequently confronted with infectious agents, including pathogenic viruses. Moreover, food antigens that can induce severe allergic reactions enter the body via the intestinal mucosa. Hence, the immunoregulation of tolerance to food allergens and commensal microbes must be initiated and maintained by the gut immune system, while forceful protective immunity to pathogens should be induced following their detection in gut-associated lymphoid tissues1,2. Peyer's patches (PPs) are central structures of the gut-associated lymphoid tissues and serve as the main initiation site of intestinal immune responses. Moreover, antigen and immune cells from PPs reach the mesenteric lymph nodes (mLNs) that serve as a second major line of defense against pathogens3.

Diverse layers of protective mechanisms, including mucosal immunoglobulin A (IgA)4 and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs)5, contribute to the maintenance of gut homeostasis and responses to intestinal pathogens. Various ILC subsets (group 1 (ILC1), group 2 (ILC2) and group 3 (ILC3)) have distinct functions in mucosal tissues, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-mediated clearance of intracellular pathogens (ILC1)6 or support of the expulsion of helminths by secretion of T helper type 2 cytokines (ILC2)7. A third type of ILCs contribute to the elimination of Gram-negative bacteria through the production of IL-22 (ILC3)8. In addition, group 3 ILCs direct the development of PPs through interaction with fibroblastic stromal cells in the embryo9. It is not clear however whether group 3 ILCs or other ILC subsets maintain their cross-talk with fibroblastic stromal cells in adult PPs.

The activation of immune responses in PPs and other secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) depends on the establishment of specialized niches for hematopoietic cells that facilitate optimized antigen acquisition, activation of T cells in the T cell zone and induction of antibody responses in the B cell zone10. The particular confines of these immune reactions are generated by fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) that not only provide structural support and guidance to immune cells but also actively participate in shaping immune responsiveness11,12. For example, FRCs of the T cell zone in lymph nodes (LNs) regulate the migration and survival of T cells by producing homeostatic chemokines such as CCL19 and CCL21, both crucial for the attraction and retention of T cells13,14,15. Podoplanin (PDPN)-expressing FRCs located at the border between the T cell zone and B cell zone and in the B cell follicles provide B cell–stimulating factors to foster antibody responses16 and generate the B cell–attracting chemokine CXCL13 during infection17. FRCs situated along the LN subcapsular sinus, commonly known as 'marginal reticular cells', are characterized by expression of the adhesion molecule MAdCAM-1 (ref. 18). Although the phenotype and function of FRCs in peripheral LNs have been studied in detail11,12, the precise role of FRCs in PPs in immunological function and PP structure is not yet known, nor is it fully clear whether FRC subsets found in LNs are present in PPs.

We found here that genetic ablation of innate immunological sensing dependent on the adaptor MyD88 in CCL19-expressing FRCs precipitated severe intestinal inflammatory disease in the aftermath of infection with an enteropathogenic virus. Delineation of the underlying mechanism revealed that unleashed trans-presentation of IL-15 on MyD88-deficient FRCs during viral infection fostered the activation of cytotoxic and non-cytotoxic group 1 ILCs and substantially accelerated clearance of the virus. However, enhanced vigilance against the viral infection came at the cost of dysregulated T cell responses with a shift from Foxp3+ regulatory T cells toward IFN-γ-producing type 1 helper T cells. We conclude that FRCs in PPs and mLNs actively regulate intestinal homeostasis by controlling local ILC1 activation and subsequent helper T cell differentiation.

Results

MyD88-independent FRC subset specification and homeostasis

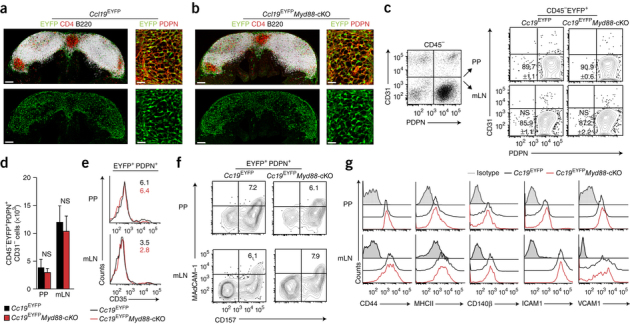

FRCs generate the cellular scaffold required for the activation of immune cells in LNs15,16, express multiple Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and respond to stimulation by the innate immune system19. We therefore reasoned that FRCs in PPs and mLNs might sense mucosal pathogens and affect immunity by directing those immune cells that respond first to the intrusion. To address this issue, we selectively abolished MyD88-dependent innate immunological sensing in FRCs through the use of mice in which loxP-flanked alleles encoding MyD88 undergo FRC-specific deletion by a transgene expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Ccl19 promoter (Ccl19-Cre), called 'Myd88-conditional-knockout' (Myd88-cKO) mice here. FRCs in PPs can be highlighted in vivo through expression of enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) from the ubiquitous Rosa26 locus (R26R) in Ccl19-CreR26R-EYFP mice (called 'Ccl19EYFP mice' here)15 (Fig. 1a). Ablation of MyD88 in FRCs did not affect PP formation (Supplementary Fig. 1a), nor did it alter the size or structural organization of PPs (Fig. 1b) or their immune-cell content (Supplementary Fig. 1b–e). Likewise, the structural organization of mLNs (data not shown) and their immune-cell composition (Supplementary Fig. 1b–e) were not affected by this FRC-specific ablation of MyD88. High-resolution in situ analysis by confocal laser-scanning microscopy revealed that the PP FRCs of both Ccl19EYFP mice and Ccl19EYFPMyd88-cKO mice formed the typical network structure and expressed the FRC marker PDPN (Fig. 1a,b), CCL21, smooth muscle actin-α and the intercellular adhesion molecule ICAM1 (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Moreover, we found that the lack of innate immunological sensing in Myd88-cKO mice did not affect expression of the Ccl19-Cre transgene in CD31−PDPN+ stromal cells of PPs or mLNs (Fig. 1c,d). The appearance of FRC subsets such as CD35+ follicular dendritic cells (Fig. 1e) or CD157+MAdCAM-1+ marginal reticular cells was independent of MyD88 in PPs and mLNs (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1g). Likewise, the expression of other canonical FRC markers was not altered by the absence of MyD88 in EYFP+ cells of PPs or mLNs (Fig. 1g). These data showed that the FRCs in PPs phenotypically resembled LN FRCs and that under homeostatic conditions, FRC-subset-differentiation patterns were independent of MyD88 when the intestinal surface was unperturbed.

Figure 1. Effect of FRC-specific MyD88 ablation on PP and mLN organization.

(a,b) Confocal microscopy of PPs from 8- to 10-week -old Ccl19EYFP mice (a) or Ccl19EYFPMyd88-cKO mice (b) showing expression of the EYFP reporter, and the distribution of CD4+ T cells and B220+ B cells in PPs (left) and the PDPN staining of the interfollicular region of FRCs (right). Scale bars, 100 μm (left) or 20 μm (right). (c) Ccl19-Cre transgene activity (assessed as EYFP fluorescence) in CD45−EPCAM−Ter119−EYFP+ stromal cells from Ccl19EYFP and Ccl19EYFPMyd88-cKO mice (above plots, right), analyzed by flow cytometry. Numbers in bottom left quadrants (right plot group) indicate percent PDPN+CD31− FRCs (mean ± s.e.m.). (d) Absolute number of Ccl19-Cre-transgene-expressing (EYFP+) CD45−EPCAM−Ter119− stromal cells in mice as in c, assessed by flow cytometry. (e,f) Flow cytometry of CD45−EPCAM−Ter119−EYFP+ stromal cells from mice as in c. Numbers in plots (e) indicate percent CD35+ follicular dendritic cells among PDPN+EYFP+ cells; numbers in top right quadrants (f) indicate percent CD157+MAdCAM1+ marginal reticular cells among PDPN+EYFP+ cells. (g) Expression of canonical FRC markers (horizontal axes) on CD45−PDPN+EYFP+ cells in PPs and mLNs of mice as in c, assessed by flow cytometry. Isotype, isotype-matched control antibody. NS, not significant (P > 0.05) (Student's t-test). Data are from two experiments with one mouse representative of four mice (a,b), are pooled from two independent experiments with n = 6 mice per genotype (c,d; mean + s.e.m. in d) or are from two experiments (e) or two experiments with one mouse representative of eight mice (f,g).

MyD88 signaling in FRCs controls antiviral ILC1 responses

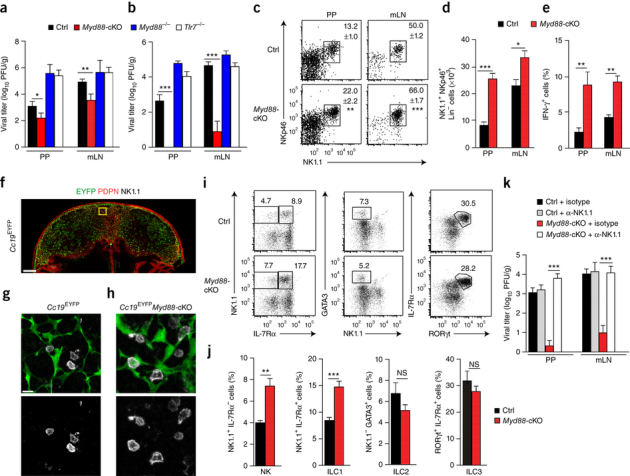

To assess whether an invasive enteric pathogen would substantially alter the activity of FRCs, we infected MyD88-sufficient mice and mice with FRC-specific MyD88 deficiency with mouse hepatitis virus (MHV). This cytopathic coronavirus is recognized via the TLR7-MyD88 pathway20, 'preferentially' targets macrophages in SLOs21 and causes severe inflammatory disease in the intestine following uptake via the oral route22. Here, we used a dose of 5 × 104 infectious particles, which led to substantial viral replication on days 3 and 6 after infection in the PPs and mLNs of MyD88-sufficient mice (Fig. 2a,b) but spared other regions of their intestine (data not shown). Viral titers were significantly lower in Myd88-cKO mice than in Myd88-sufficient mice on day 3 after infection, and infectious particles were almost completely eliminated from the Myd88-cKO mice on day 6 (Fig. 2a,b). This finding was unexpected, because global deficiency in MyD88 or TLR7 resulted in uncontrolled viral spread, with viral titers more than 10,000-fold higher in mice with such global deficiency than in Myd88-cKO mice (Fig. 2a,b). Moreover, the virus was purged from the spleen and liver of Myd88-cKO mice at day 6 (Supplementary Fig. 2a), which indicated that potent immunological effector mechanisms had prevented systemic spread of the pathogen.

Figure 2. Population expansion and reactivity of group 1 ILCs in the absence of MyD88 signaling in FRCs.

(a,b) Viral titers in the PPs and mLNs of Myd88-cKO mice, their Cre-negative littermates (Ctrl), Tlr7−/− mice or MyD88−/− mice (key) at day 3 (a) or day 6 (b) after oral infection with 5 × 104 plaque-forming units (PFU) of MHV. (c) Flow cytometry of the ILC1 subset in in PPs of Myd88-sufficient (Ctrl) and Myd88-cKO mice on day 3 after infection as in a, gated from CD45+CD3−CD19−GR1− cells. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate percent NKp46+NK1.1+ cells (mean ± s.e.m.). (d) Quantification of results in c. (e) IFN-γ-producing cells in the CD45+CD3−NK1.1+ population in mice as in c, assessed by flow cytometry. (f–h) Confocal microscopy of EYFP fluorescence and the localization of NK1.1+ cells in the PPs of a Ccl19EYFP mouse at day 3 after infection with MHV (f), and enlargement of the interfollicular region (outlined area in f) to identify Ccl19-Cre-transgene-expressing cells in close proximity to NK1.1+ cells in Ccl19EYFP mice (g) and Ccl19EYFPMyd88-cKO mice (h) at day 3 after infection with MHV. Scale bars, 100 μm (f) or 10 μm (g,h). (i) Flow cytometry of CD45+CD3−CD19−GR1− cells from the PPs of Myd88-sufficient (Ctrl) and Myd88-cKO mice at day 3 after infection with MHV. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate percent NK1.1+IL-17Rα− NK cells (left) or NK1.1+IL-17Rα+ cells (ILC1) (right) (left column); GATA3+NK1.1− cells (ILC2) (middle column); or IL-17Rα+RORγt+ cells (ILC3) (right column). (j) Frequency of ILC subsets as in i. (k) Viral titers in the PPs and mLNs of Myd88-sufficient (Ctrl) and Myd88-cKO mice treated with NK1.1-depleting antibody (+ α-NK1.1) or isotype-matched control antibody (+ isotype), assessed at day 6 after oral infection with MHV. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (Student's t-test (a–e,j) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post-test (k)). Data are pooled from four independent experiments (a,b; mean + s.e.m.) or three experiments (c–e,k; mean + s.e.m. in d,e,k), are from two experiments with one mouse representative of three mice (f–i) or are representative of two experiments (j; mean + s.e.m.).

The accelerated viral control in Myd88-cKO mice as early as on day 3 after infection suggested that innate antiviral immune cells had been activated by the FRC-specific MyD88 deficiency. Indeed, we found significantly more cells expressing the activating natural killer cell (NK cell) receptors NK1.1 and NKp46 in the PPs and mLNs of Myd88-cKO mice than in those of Myd88-sufficient early after infection (Fig. 2c,d). Moreover, production of the antiviral effector cytokine IFN-γ was much greater in the NK1.1+ cells of Myd88-cKO mice than in their counterparts from Myd88-sufficient mice (Fig. 2e). Histological analysis of PPs from infected mice at day 3 after infection with MHV revealed that NK1.1+ cells were located mainly in the interfollicular regions (Fig. 2f). Moreover, these cells were in close contact with FRCs expressing the Ccl19-Cre transgene, both in the presence of MyD88 (Fig. 2g) and in its absence (Fig. 2h) in FRCs. The frequency and number of both non-cytotoxic group 1 ILCs expressing the cytokine receptor IL-7Rα and IL-7Rα-negative NK cells were increased when immunological sensing was altered in the FRCs of PPs (Fig. 2i,j and Supplementary Fig. 2b,c) and mLNs (Supplementary Fig. 2b,c). Control staining revealed that NK1.1+IL-7Rα− group 1 ILCs, but not IL-7Rα+ group 1 ILCs, expressed the signature transcription factor Eomes (Supplementary Fig. 2d). FRC-specific MyD88 deficiency had a positive effect on the population expansion and activation of group 1 ILCs, whereas the size of the ILC2 and ILC3 compartments in PPs (Fig. 2i,j) and mLNs (Supplementary Fig. 2b,c) was slightly reduced relative to their size in Myd88-sufficient mice. To assess whether this enhanced antiviral immunity was exclusively dependent on group 1 ILCs, we ablated NK1.1-expressing cells using a well-established depletion protocol23 (Supplementary Fig. 2e,f). Antibody-mediated depletion of group 1 ILCs completely restored viral replication in all organs of Myd88-cKO mice but had little effect on viral replication in Myd88-sufficient mice (Fig. 2k). These data indicated that the FRCs in PPs and mLNs were able to function as potent regulators of antiviral immunity and that this function was exerted via control of group 1 ILCs.

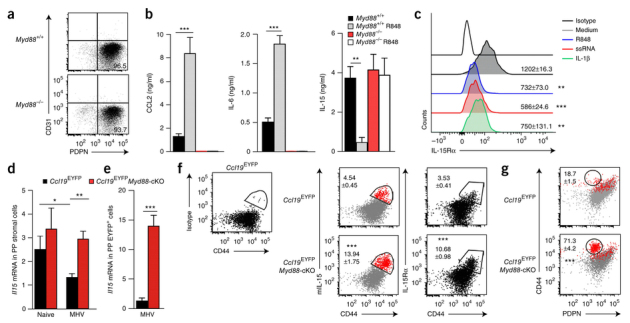

FRCs restrain ILC1 activity through IL-15 deprivation

The differentiation and activation of cytotoxic and non-cytotoxic ILCs is stringently regulated by cytokines24. In addition, NK cell activity is controlled by inhibitory receptors that bind to major histocompatibility complex class I molecules25. Since MyD88-deficient FRCs in PPs and mLNs did not show altered expression of major histocompatibility complex class I during intestinal infection with MHV (data not shown), we established an in vitro cell-culture system (Fig. 3a) to probe FRC cytokine responses following exposure to R848, a synthetic agonist of TLR7 and TLR8. We found that MyD88-sufficient FRCs responded to stimulation of TLR7 with considerable production of the inflammatory mediators IL-6 and CCL2, whereas FRCs lacking MyD88 failed to respond to stimulation with R848 (Fig. 3b). Exposure to this TLR7 ligand led to a substantial reduction in the production of IL-15 by MyD88-sufficient FRCs, whereas MyD88-deficient FRCs continued to produce large amounts of this NK cell– and ILC1-activating cytokine (Fig. 3b). Since IL-15 acts mainly in a cell-contact-dependent manner via trans-presentation by IL-15 receptor α-chain (IL-15Rα)26, we used expression of IL-15Rα as an additional marker of differential FRC activation. Expression of IL-15Rα in MyD88-sufficient FRCs was significantly reduced after stimulation with the TLR7 ligands R848 or single-stranded RNA or with IL-1β (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3). MyD88-dependent regulation of the production of IL-15 in vivo was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis showing significantly higher expression of Il15 mRNA in CD45− PP stromal cells from MyD88-cKO mice than in those from Myd88-sufficient mice (Fig. 3d) and in EYFP+ cells sorted from the PPs of Ccl19EYFPMyd88-cKO mice than in those sorted from the PPs of Ccl19EYFP mice (Fig. 3e), on day 3 after infection. Moreover, flow cytometry revealed that IL-15 was detectable on the surface of EYFP+ cells expressing the cell-adhesion molecule CD44 (Fig. 3f). The lack of MyD88 substantially increased not only the amount of surface-bound IL-15 but also expression of the IL-15-trans-presenting molecule IL-15Rα (Fig. 3f). Back-gating showed that the enhanced IL-15 production under conditions of MyD88 deficiency could be attributed to PDPNdimCD44hi FRCs (Fig. 3g), which suggested that a distinct FRC subpopulation activated group 1 ILCs via trans-presentation of IL-15.

Figure 3. MyD88-dependent regulation of IL-15 in PP FRCs.

(a) Flow cytometry of fibroblastic stromal cells isolated from the PPs of C57BL/6 Myd88+/+ or Myd88−/− mice and cultured in vitro for 7 d. Numbers indicate percent CD31−PDPN+ cells (bottom right quadrant). (b) Production of the chemokine CCL2 and the cytokines IL-6 and IL-15 by CD45−CD31− stromal cells from the PPs of Myd88+/+ (Ctrl) or Myd88−/− mice without R848 or at 24 h after exposure to R848 (key). (c) Expression of IL-15Rα on CD45−PDPN+ cells after exposure to medium, R848 (100 ng/ml), single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) (100 ng/ml) or IL-1β (10 ng/ml) (above lines), assessed by flow cytometry. Numbers, mean fluorescence intensity of IL-15Rα (± s.e.m.). Top line, staining with isotype-matched control antibody. (d,e) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Il15 mRNA in CD45− PP stromal cells (d) or CD45−EYFP+PDPN+ PP FRCs (e) sorted by flow cytometry from Ccl19EYFP and Ccl19EYFPMyd88-cKO mice before infection (Naive) and on day 3 after infection with MHV. (f) Binding of isotype-matched control antibody (Isotype) on CD44hi cells from a Ccl19EYFP mouse (left), and expression of membrane-bound IL-15 (mIL-15) (middle) and IL-15Rα (right) on CD44hi cells from Ccl19EYFP and Ccl19EYFPMyd88-cKO mice on day 3 after infection with MHV, assessed by flow cytometry. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate percent mIL-15+CD44+ cells (middle) or IL-15Rα+CD44+ cells (right) (mean ± s.e.m.). (g) Expression of membrane-bound IL-15 on PDPN+ FRCs, assessed with back-gating (red). Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate percent CD44+PDPN+ cells among mIL15+ cells (± s.e.m.). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (one- way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test (b,c) or Student's t-test (d–g)). Data are from one experiment representative of four independent experiments (a) or two experiments (b; mean + s.e.m.) or are pooled from three independent experiments (c) or two independent experiments with n ≥ 4 mice per group (d–g; mean + s.e.m. in d,e).

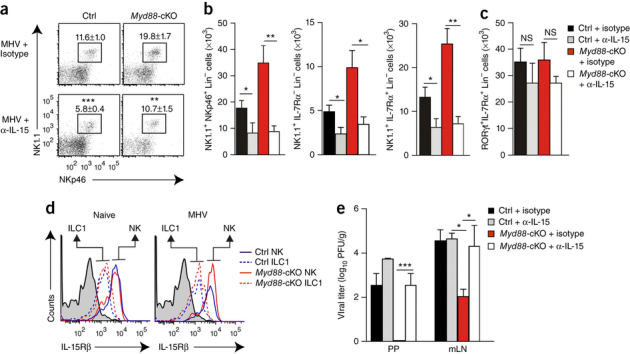

To assess whether IL-15 is the dominant FRC-derived factor that mediates the population expansion of group 1 ILCs and controls viral replication, we applied a neutralizing antibody to IL-15 (anti-IL-15) during the course of the infection starting 1 d before infection with MHV. We found that treatment with anti-IL-15 efficiently blunted the exaggerated population expansion of group 1 ILCs in Myd88-cKO PPs (Fig. 4a,b). Notably, neutralization of IL-15 led to a reduced frequency (Fig. 4a) and absolute number (Fig. 4b) of group 1 ILCs in Myd88-sufficient mice and diminished the ILC3 population both in Myd88-sufficient PPs and in Myd88-cKO PPs (Fig. 4c). These data confirmed the importance of IL-15 for ILC homeostasis in PPs24 and indicated that innate immunological signaling in FRCs functioned as an important regulatory switch for this IL-15-driven ILC1 proliferation. Assessment of the expression of CD122, a component of the IL-15 receptor, on Eomes1+ and Eomes1− ILC1 subsets revealed no major change in expression of the IL-15 receptor β-chain (CD122) under conditions of FRC-specific MyD88 deficiency (Fig. 4d), indicative of an ILC1-extrinsic regulation circuit. Notably, in vivo neutralization of IL-15 disinhibited viral replication in Myd88-cKO mice, while Myd88-sufficient mice showed only minor changes in viral load (Fig. 4e). Together these data revealed that the ILC1 activity in PPs and mLNs was controlled almost exclusively via a single cytokine derived from a particular FRC subset. Moreover, it appeared that innate immunological activation of FRCs via direct recognition of viral RNA or through IL-1β-mediated stimulation was critical for the adjustment of ILC1 reactivity.

Figure 4. FRC-dependent population expansion and activation of group 1 ILCs and NK cells.

(a,b) Frequency (a) and absolute number (b) of group 1 ILCs among CD45+CD3−CD19−GR1− cells from Myd88-cKO mice and their Cre-negative littermates (Ctrl) treated with neutralizing antibody to IL-15 (α-IL-15) or isotype-matched control antibody (isotype) before and during infection with MHV, assessed on day 3 after infection by staining for NK1.1, NKp46 and IL-7Rα. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas (a) indicate percent NK1.1+NKp46+ cells (mean ± s.e.m.). (c) Quantification of RORγt-expressing group 3 ILCs in mice as in a,b. (d) Expression of CD122 (IL-15Rβ) on IL-7Rα+EOMES− group 1 ILCs and IL-7Rα−EOMES+ NK cells (brackets and arrows above plots) from the PPs of Myd88-cKO mice and their Cre-negative littermates (key), assessed before (Naive) and on day 3 after infection (MHV). Shaded curves, isotype-matched control antibody. (e) Viral titers in PPs and mLNs of mice as in a,b, assessed on day 6 after infection. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (Student's t-test (a–c) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test (e)). Data are pooled from two independent experiments with n = 6 mice per group (a–c,e; mean + s.e.m. in b,c,e) or are from one experiment representative of two experiments with similar results (d).

FRCs regulate homeostatic ILC1 and NK cell maintenance

To assess whether FRC-derived IL-15 not only controls the proliferation and activity of group 1 ILCs and/or NK cells during an infection but also contributes to their homeostasis, we selectively abolished IL-15 expression in FRCs by generating Ccl19-CreIl15fl/fl mice (called 'Il15-cKO' mice here). We found that FRC-specific ablation of IL-15 affected neither PP formation (Supplementary Fig. 4a) nor the composition of T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes in this SLO (Supplementary Fig. 4b). NK1.1+NKp46+ cells were almost completely absent under conditions of FRC-specific loss of IL-15, whereas neither the ILC2 compartment nor the ILC3 compartment was significantly affected (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 4c,d). Since the Ccl19-Cre transgene was active in less than 0.08% of non-endothelial bone marrow stromal cells (Supplementary Fig. 4e), we concluded that the IL-15-expressing FRCs in gut-associated SLOs generated an essential niche for the maintenance of group 1 ILCs and NK cells under homeostatic conditions.

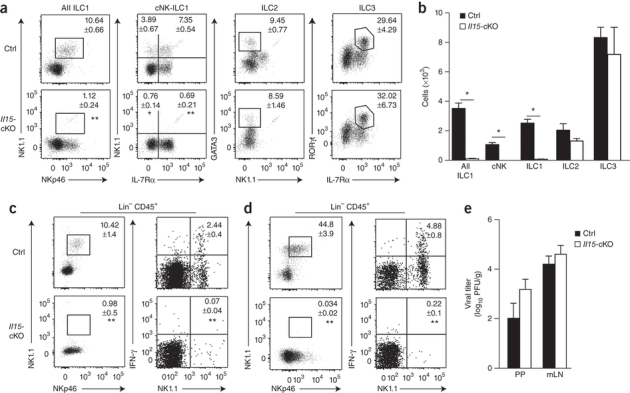

Figure 5. Activity of group 1 ILCs and NK cells in the absence of IL-15 expression in FRCs.

(a) Flow cytometry of CD45+CD3−CD19−GR1− cells from the PPs of Il15-cKO mice and their Il15-sufficient littermates (control (Ctrl)) to distinguish ILC subsets (above plots) through the use of various combinations of staining for NK1.1, NKp46, IL-7Rα and GATA3. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas or quadrants indicate percent cells in each subset (mean ± s.e.m.). (b) Absolute number of various ILC populations (horizontal axis) in the PPs of naive Il15-sufficient or Il15-cKO mice. (c,d) Flow cytometry of CD45+CD3−CD19−GR1−NK1.1+ cells in the PPs (c) and mLNs (d) of Il15-sufficient or Il15-cKO mice on day 3 after infection with MHV. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas (left) indicate percent NK1.1+NKp46+ cells; numbers in top right quadrants (right) indicate percent IFN-γ+ cells (mean ± s.e.m. for both). (e) Viral titers in the PPs and mLNs of Il15-sufficient or Il15-cKO mice at day 6 after infection with MHV. *P < 0.001 (Student's t-test). Data are pooled from two or three independent experiments with n = 5 mice per genotype (a–d; mean + s.e.m. in b) or are pooled from two independent experiments with n = 7–8 mice per group (e; mean + s.e.m.).

Next we assessed to what extent such specific ablation of Il15 in FRCs affected the activation of ILC1- and/or NK cell–mediated antiviral immunity. Even under inflammatory conditions, we found an almost complete absence of NK1.1+NKp46+ cells in the PPs (Fig. 5c) and mLNs (Fig. 5d) of Il15-cKO mice. Moreover, other CD45+Lin− cells (i.e., group 2 and group 3 ILCs) did not produce IFN-γ during the early phase of the viral infection in Il15-cKO mice (Fig. 5c,d), which indicated that other sources of IL-15, such as dendritic cells or macrophages27,28, failed to compensate for the lack of this growth factor in the FRC niche. Consistent with the results of the anti-NK1.1 ablation experiment (Fig. 2k), we found only a moderate effect of the selective loss of group 1 ILCs and/or NK cells on the control of viral replication (Fig. 5e). Thus, we concluded that the FRCs built and maintained an exclusive IL-15-dependent niche for the maintenance of group 1 ILCs and/or NK cells in the PPs and mLNs and controlled antiviral immunity in gut-associated SLOs through cessation of IL-15 production.

Innate immunological sensing in FRCs restricts gut inflammation

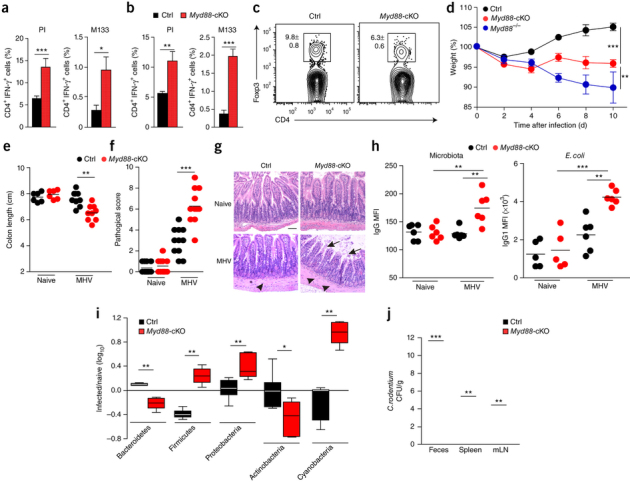

Early IFN-γ production by NK cells has been shown to be important for the differentiation of helper T cell subsets29. Accordingly, the greater abundance of IFN-γ-secreting group 1 ILCs in Myd88-cKO mice was associated with an elevated frequency of antiviral CD4+ T cells that secreted IFN-γ in the PPs and mLNs on day 10 after infection with MHV (Fig. 6a,b and Supplementary Fig. 5a,b) but only moderate proliferation of IL-17-producing helper T cells (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Notably, MyD88 deficiency in FRCs precipitated a significantly lower abundance of regulatory T cells expressing the transcription factor Foxp3 in the PPs of Myd88-cKO mice than that in the PPs of Myd88-sufficient mice (Fig. 6c), which suggested that immunological regulation in the small intestine might have been compromised. Indeed, the lack of innate immunological sensing in FRCs led to substantial weight loss in MHV-infected Myd88-cKO mice (Fig. 6d), despite their accelerated viral clearance (Fig. 2a). As expected, global deficiency in MyD88, which permitted almost unrestricted replication of the cytopathic virus (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5d), was associated with a worsened clinical appearance (Fig. 6d). Gross pathological analysis revealed that the intestinal wall of Myd88-cKO mice was considerably inflamed on day 10 after MHV infection, with a significantly shorter colon length than that of Myd88-sufficient mice (Fig. 6e). Histopathological examination confirmed that the enhanced immunopathology in the small intestine of Myd88-cKO mice (Fig. 6f) included an edematous muscular layer and blunting of villi (Fig. 6g). Those pathological changes were associated with a greater antibody response to intestinal microbiota such as Escherichia coli than that of Myd88-sufficient mice (Fig. 6h), which indicated that the integrity of the epithelial barrier was compromised in infected Myd88-cKO mice. Such weakening of the epithelial barriers in MHV-infected Myd88-cKO mice was accompanied by pronounced changes in the composition of the microbiome (Fig. 6i and Supplementary Fig. 5e), whereas the composition of the commensal flora in naive mice was not affected by FRC-specific MyD88 deficiency (Supplementary Fig. 5e). The finding that Myd88-cKO mice showed significantly lower resistance to colonization by other intestinal pathogens such as Citrobacter rodentium on day 12 after infection with MHV, relative to that of Myd88-sufficient mice (Fig. 6j), further emphasized the importance of immunoregulatory functions of FRCs and their ability to adjust global immune responsiveness in the intestine.

Figure 6. Innate immunological signaling in FRCs regulates intestinal homeostasis.

(a,b) Frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells among CD4+ T cells obtained from the PPs (a) and mLNs (b) of Myd88-cKO mice and their Cre-negative littermates (Ctrl) (key) at day 10 after oral infection with MHV and then stimulated in vitro with phorbol ester PMA and ionomycin (PI) or the MHV peptide M133 (above plots). (c) Flow cytometry of cells from the PPs of Myd88-cKO mice and their Cre-negative littermates (above plots) at day 10 after oral infection with MHV. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate percent Foxp3+CD4+ T cells (mean ± s.e.m.). (d,e) Weight change in Myd88-cKO mice and their Cre-negative littermates (key) at various times (horizontal axis) after oral infection with MHV, relative to initial weight (set as 100%). (e) Colon length of Myd88-cKO mice and their Cre-negative littermates (key) left uninfected (Naive) or after infection as in c. (f) Histopathological analysis of ileal sections from mice as in e. (g) Microscopy of ileal sections from mice as in e: arrowheads indicate muscular layer; arrows indicate villi. Scale bar, 100 μm. (h) Binding of serum IgG to microbiota (left) or E. coli (right) in mice as in e, as determined by flow cytometry. (i) Ileal microbiota composition (horizontal axis) in mice infected as in c, relative to that in their naive counterparts. (j) Bacterial load in the feces, spleen and mLNs of Myd88-cKO mice and their Cre-negative littermates (key) infected with 2 × 109 colony-forming units of C. rodentium on day 12 after infection with MHV, assessed at day 6 after bacterial infection. Each symbol (e,f,h) represents an individual mouse; small horizontal lines indicate the mean. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (Student's t-test (a–c,e,j), two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post-test (d), Mann-Whitney U-test (f, i) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post analysis (h)). Data are pooled from three independent experiments with n = 6–8 mice per group (a,b; mean + s.e.m.) or two independent experiments with n = 6–9 mice per group (c–e,j; mean ± s.e.m. in d), are representative of two experiments with n = 5, 6 or 11 mice per group (f,h) or two experiments (g) or are from one experiment representative of two independent experiments with n = 6 mice per group (i; mean ± interquartile range).

Discussion

Genetic association studies have provided evidence that multiple TLRs are involved in balancing the sensing of microbes in chronic inflammatory disease of the intestine30,31. Moreover, experimental studies have revealed that innate signal integration via the shared adaptor MyD88 promotes epithelial integrity32,33. It has been suggested that ILCs secreting cytokines involved in chronic intestinal inflammation, such as IL-17, IL-22 or IFN-γ, serve as critical sentinels by translating innate immunological signals for the activation of adaptive immunity34. Our study has identified a MyD88-dependent pathway of ILC regulation that is called into action once the epithelial barrier has been breached by a pathogen. Our results showed that antiviral ILC1 and NK cell responses in PPs and mLNs were efficiently regulated through limiting of the provision of IL-15 by FRCs. Both direct recognition of viral RNA via TLR7 and indirect activation of FRCs via IL-1β led to activation of this potent control mechanism. It appears that this direct and simple regulatory pathway acts proximal to more elaborate immunoregulatory circuits that involve the balancing of helper T cell differentiation and the generation of regulatory T cells.

ILCs are recognized as the main drivers of the diverse immune responses needed to maintain mucosal surface integrity and protection5. However, these cells are almost completely unresponsive to microbial ligands35, which suggests that ILCs utilize indirect means to regulate their activation and functionality after microbial invasion. The data presented here suggest that FRCs in gut-associated SLOs function as an intermediate cell to regulate ILC1 function specifically via IL-15. The importance of IL-15 production by FRCs was emphasized by the almost complete absence of group 1 ILCs and/or NK cells in mice that lacked Il15 expression in FRCs. Thus, it appears that FRCs in PPs and mLNs form a highly specialized niche for group 1 ILCs and/or NK cells. That interpretation is in line with the finding that IL-15 production by myeloid cells is not an exclusive regulator of the homeostasis of group 1 ILCs and/or NK cells in SLOs27. Thus, it appears that IL-15 production by FRCs secures the maintenance of group 1 ILCs and/or NK cells in SLOs and prevents exaggerated innate immune reactions through MyD88-dependent restriction of IL-15 production under conditions in which myeloid cells start to provide IL-15 via its trans-presentation by IL-15Rα36 to other activated immune cells.

The conceptual framework of intestinal immunoregulation outlined by published studies1,37 predicts that innate immune signaling in intestinal tissues needs to be equilibrated at levels that preserve both tissue repair and host defense. Indeed, the absence of MyD88 signaling in all cells rendered the host highly susceptible to infection with cytopathic murine coronavirus. This virus exhibits strong tropism for myeloid cells, and the provision of type 1 interferons is needed to prevent cell death20,21. Moreover, type 1 interferons are important stimulators of NK cells38 and potentiate early antiviral immune responses, for example, through the stimulation of IL-15 production by dendritic cells39,40. Interestingly, IL-15-mediated counter-balancing of this protective mechanism was induced in FRCs immediately after the recognition of viral RNA via TLR7, following exposure to IL-1β and the transmission of these innate immunological signals via MyD88. Our finding that the proliferation and activity of group 1 ILCs and NK cells in PPs and mLNs was controlled almost exclusively via IL-15 is in line with the finding that intraepithelial group 1 ILCs are highly responsive to IL-15 (ref. 41). It remains to be determined whether the ILC1 subset, and other ILC subsets, outside of PPs and mLNs are subject to regulation by stromal cells. It is possible that mesenchymal stromal cells of the lamina propria, such as myofibroblasts or mural cells, exert immunoregulatory functions comparable to those of FRCs in PPs. Clearly, lamina propria mesenchymal stromal cells not only form the scaffold of the tissue but also provide a plethora of positive and negative regulatory factors that impinge on innate and adaptive immune processes42.

In sum, our study has extended the current paradigm of immunoregulation in the intestine and has revealed innate immunological sensing in FRCs as a key mechanism for the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. It will be important to further delineate the FRC-ILC axis of intestinal immunoregulation to facilitate the targeting of processes that efficiently restrain intestinal immunopathology.

Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6/N (B6) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Germany). Myd88−/− and Tlr7−/− mice were obtained from the Institute for Laboratory Animal Sciences at the University of Zürich. BAC-transgenic C57BL/6N-Tg(Ccl19-Cre)489Biat (Ccl19-Cre) mice have been previously described15 and were crossed with R26R-EYFP mice43. To specifically ablate MyD88 or IL-15 in FRCs, Ccl19-Cre and Ccl19EYFP mice were crossed with mice with loxP-flanked Myd88 alleles (Jackson Laboratory) or with mice with loxP-flanked Il15 alleles. Constitutive ablation of Il15 was achieved by flanking exon 5 with two loxP sequences by standard germline recombination in embryonic stem cells. All mice were on the C57BL/6N genetic background and were maintained in individually ventilated cages and were used between 8 and 10 weeks of age. As control animals, co-housed and Cre-negative littermate mice have been used in all experiments. Experiments were performed in accordance with federal and cantonal guidelines (Tierschutzgesetz) under permission numbers SG11/05, SG09/14 and SG10/14 following review and approval by the Cantonal Veterinary Office (St. Gallen, Switzerland).

Viral and bacterial infection.

Mice were infected with MHV A59, orally by gavage with 5 × 104 plaque-forming units as previously described21. Mice were sacrificed and organs were stored at −70 °C until further analysis. MHV titers were determined by standard plaque assay using L929 cells44. L929 cells were purchased from the European Collection of Cell Cultures. A nalidixic-acid-resistant strain of Citrobacter rodentium (ICC169) was grown overnight at 37 °C in Luria broth supplemented with nalidixic acid (50 μg/ml, Sigma Aldrich). Mice were fed, on average, 2 × 109 bacteria by oral gavage at day 12 after MHV infection (resolution phase). Organs were harvested at day 6 after infection, homogenized and cultured on selective plates45.

Preparation of stromal cells.

PPs or mLNs were dissected into small pieces and transferred into a 24-well dish filled with RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% FCS, 20 mM HEPES (all from Lonza), 1 mg/ml collagenase D (Sigma) and 25 μg/ml DNaseI (Applichem). Dissociated PPs or LNs were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After enzymatic digestion, cell suspensions were washed with PBS containing 0.5% FCS and 10 mM EDTA. To enrich for fibroblastic stromal cells, hematopoietic cells were depleted by incubating the cell suspension with MACS anti-CD45 and anti-Ter119 microbeads and passing over a MACS LS column (Miltenyi Biotec). Cell sorting was performed using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences) or a S3 cell sorter (Biorad). For in vitro assays, PP or mLN fibroblastic stromal cells were cultured for 7 d in RPMI with 10% FCS, and 5 × 104 cells were stimulated with 100 ng of R848 or left untreated. Supernatants were collected after 24 h, and IL-6 and CCL2 concentrations were determined by cytomeric bead array (CBA, BD biosciences) and IL-15 concentration was determined by ELISA (Abcam).

Flow cytometry.

Single-cell suspensions were incubated for 20 min at 4 °C in PBS containing 1% FCS and 10 mM EDTA with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies (Supplementary Table 1). Cells were acquired with a FACSCanto (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar Inc.). Analysis of EOMES, GATA-3, TBET, Foxp3 and RORγt expression was performed using the Foxp3/transcription factor staining buffer set from eBioscience, according the manufacturer's instructions.

Analysis of NK1.1+ and CD4+ T cells responses was performed using cytokine production after stimulation with phorbolmyristateacetate (PMA, 50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (500 ng/ml; both purchased from Sigma) in the presence of brefeldin A (5 μg/ml) for 3 h at 37 °C. For peptide-specific cytokine production, cells were restimulated with M133 peptide (TVYVRPIIEDYHTLT; GenScript) in the presence of brefeldin A (5 μg/ml) for 4 h at 37 °C. For intracellular staining, restimulated cells were surface-stained and fixed with cytofix-cytoperm (BD Biosciences) for 20 min. Fixed cells were incubated at 4 °C for 40 min with permeabilization buffer (2% FCS, 0.5% Saponin in PBS) containing antibodies to IFN-γ and to IL-17A (Supplementary Table 1). Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCanto (Becton Dickinson), data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.).

Histology.

PPs and mLNs were fixed overnight in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (Merck) at 4 °C under agitation. Fixed organs were embedded in 4% low melting agarose (Invitrogen) in PBS and sectioned with a vibratome (Leica VT-1200). 20- to 30-μm-thick sections were blocked in PBS containing 10% FCS, anti-Fcγ receptor (Supplementary Table 1) and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma). Sections were incubated over night at 4 °C with the following antibodies: anti-PDPN, anti-B220, anti-CD31, anti-CD4, anti- smooth muscle actin-α, anti-EYFP and anti-CCL21 (Supplementary Table 1). Unconjugated antibodies were detected with the following secondary antibodies: Dylight649-conjugated anti-rat-IgG, Alexa488-conjugated anti-rabbit-IgG, Dylight549-conjugated anti-syrian hamster-IgG and Dylight549-conjugated Streptavidin (Supplementary Table 1). Microscopy was performed using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM-710) and images were processed with ZEN 2010 software (Carl Zeiss, Inc.) and Imaris (Bitplane).

Assessment of intestinal inflammation.

Intestinal tissues were removed and cleaned and the distal ileum was immediately fixed in neutral buffered 10% formalin solution. Two to four 5-μm-thick sections of the ileum from each mouse were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Each sample was graded for the following four criteria on a scale of 0–3 (0, none; 1, mild; 2, intermediate; 3 severe): leukocyte infiltration in the lamina propria; iedema; villus distortion; and presence of markers of severe inflammation such as crypt abscesses, submucosal inflammation, and ulcers. Scores for each criterion were added to generate an overall inflammation score for each sample. Sections were scored in a blinded fashion by two independent observers.

NK cell depletion and IL-15 neutralization.

Mice were administrated 400 μl/mouse of a NK1.1-depleting monoclonal antibody (clone PK136; produced in-house) at days −3, −1 and 2 of infection (day 0)23. Efficacy of NK1.1+ cell depletion was assessed by flow cytometry. For neutralization of IL-15, mice were given daily intraperitoneal injection of 25 μg/mouse of an IL-15-neutralizing antibody (eBiosciences, clone AIO.3), from day −1 to day 2 of the infection.

Detection of bacteria specific IgG.

Serum samples from mice at day 10 after infection with MHV were heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min. Heat-inactivated sera were incubated with cultivable ileal microbiota or E. coli K12 for 30 min at 4 °C. A647-labeled anti-mouse IgG was used for detection in flow cytometry (Supplementary Table 1). Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCanto (BD Biosciences). Data was analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Total cellular RNA was extracted from homogenized tissues and sorted cells using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was prepared using cDNA archive kit (Applied Biosystems), and quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the Light Cycler-FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche Diagnostics) on a LightCycler machine (Roche Diagnostics). mRNA expression was measured using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR primers (Qiagen).

Microbiota analysis.

For microbial composition analysis, the ileal content of naive or MHV-infected Myd88-cKO and their Cre-negative littermates was used. Microbial composition was assessed by a 16S high-throughput amplicon analysis. The 16S rRNA gene segments spanning the variable V5 and V6 regions were amplified from DNA from ileal content samples, using a multiplex approach with the barcoded forward fusion primer 5′-CCATCTCATCCCTGCGTGTCTCCGACTCAG BARCODE ATTAGATACCCYGGTAGTCC-3′ in combination with the reverse fusion primer 5′-CCTCTCTATGGGCAGTCGGTGATACGAGCTGACGACARCCATG-3′. The PCR-amplified 16S V5-V6 amplicons were purified and prepared for sequencing on the Ion torrent PGM system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Life Technologies). Samples with over 500 reads were accepted for analysis. Data analysis was performed using the QIIME pipeline version 1.8.0. Operational taxonomic units were picked using UCLUST with a 97% sequence identity threshold, followed by taxonomy assignment using either the latest Greengenes database.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed with Graphpad Prism 5.0 using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney test. Longitudinal comparison between different groups was performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test or two-way ANOVA with Benferroni's post-test. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Supplementary Information

Integrated supplementary information

(a) PP numbers in 8–10 week old Cre-negative littermate (Ctrl) and Myd88-cKO mice (n = 11 mice; each dot represents one individual mouse, bars indicate mean). (b–e) Composition of hematopoietic cells in PPs and mLNs as determined by flow cytometry; values indicate means ± s.e.m. of the indicated cell population (n = 8 mice, pooled data from 2 independent experiments). (f) Confocal microscopic analysis of Ccl19-Cre transgene activity (assessed as EYFP fluorescence) in interfollicular regions of PPs from 8-10 week old Ccl19EYFP and Ccl19EYFP Myd88-cKO mice; co-staining with FRC markers is indicated (scale bars = 10 μm); representative sections from one out of four mice. (g) Composition of the indicated EYFP+ fibroblastic stromal cell subsets in Ccl19EYFP and Ccl19EYFP Myd88-cKO mice as determined by the indicated marker combination (mean ± s.e.m., n = 8 mice, pooled from 2 independent experiments). Statistical analyses using Student’s t test did not reveal significant differences between Ccl19EYFP and Ccl19EYFP Myd88-cKO mice.

(a) Mice were infected with 5 × 104 PFU of MHV and viral titers were determined in Cre-negative littermate (Ctrl) and Myd88-cKO mice at day 6 post infection in spleen and liver (mean of log-transformed values ± s.e.m., n = 8 mice per group, pooled from 2 independent experiments). (b, c) ILC subset analysis in indicated organs. Representative plots show ILCs subsets in CD45+CD3− CD19−GR1− cells (Lin−). Bar graphs show frequencies (b) and absolute numbers (c) of ILC subsets in mLNs or PP on day 3 post infection (mean percentage or number ± s.e.m. of indicated cell populations, n ≥ 6 mice per group, pooled from 3 independent experiments). (d) Confirmation of ILC1 and NK cell identity using intracellular staining for EOMES; representative data from one out of three independent experiments. (e) Representative dot plots showing reduction of NK1.1+NKp46+ cells on day 3 of the infection following application of anti-NK1.1 antibody. (f) Frequencies of ILC subsets in PPs on day 3 post infection in anti-NK1.1 antibody-treated mice (mean percentage ± s.e.m. of CD45+ CD3−CD19−GR1− (Lin−) cells, n = 6 mice per group, pooled from 3 independent experiments). Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ND, non-detectable)

CD45− stromal cells were isolated from PPs of C57BL/6 or Myd88−/− mice by magnetic sorting. After 7 days in culture, expression of IL-15Rα on CD45− PDPN+ cells was determined by flow cytometry following exposure to IL-1β or the TLR7-ligands R848 or ssRNA 40 LyoVec at the indicated concentrations (ng/ml) (mean MFI ± s.e.m.). Pooled values from 3 independent experiments with 2 replicates per condition. Statistical analysis was performed using one way ANOVA with Tukey’s posttest (*, P < 0.05; **; P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

(a) Confocal microscopic analysis of Ccl19-Cre transgene activity (assessed as EYFP fluorescence) and distribution of CD4+ T cells and B220+ B cells in PPs of 8–10 week old Ccl19EYFP and Ccl19EYFP Il15-cKO mice (scale bar = 100 μm). (b) Abundance of indicated cell populations in PPs as determined by flow cytometry (mean ± s.e.m., n = 5 mice, pooled data from 3 independent experiments). (c,d) ILC subset analysis in mLNs of Cre-negative littermate (Ctrl) and Il15-cKO mice. (c) Plots from the CD45+Lin− cell fraction (mean ± s.e.m., n = 5 mice, pooled data from 3 independent experiments). (d) Absolute numbers of the indicated ILC populations in Cre-negative littermate (Ctrl) and Il15-cKO naive mice. (e) Flow cytometric analysis of EYFP reporter gene expression in bone marrow stromal cells from 8 wk old Ccl19EYFP mice (mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 mice) Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (***, P< 0.001)

(a,b) Representative flow cytometric analyses of IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin (PI) or MHV peptide M133 in PPs (a) and mLNs (b) on day 10 post infection. Values indicate percentage of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells. (c) CD4+ T cells producing IL-17 in PP and mLN following PI incubation. Values indicate mean percentage ± s.e.m., n = 8 mice, pooled from two independent experiments. (d) Viral titers on day 10 post infection in the indicated organs (mean ± s.e.m., n = 4 mice, pooled data from 2 independent experiments; ND, not detectable). (e) Ileal microbiota composition in naive and infected (day 10) Cre-negative littermate (Ctrl) and Myd88-cKO mice. Values indicate mean relative abundance ±s.e.m., n = 6 mice, one representative of two experiments of the indicated bacterial taxa. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; NS, not significant).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figures 1–5 and Supplementary Table 1 (PDF 1225 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank K.J. Maloy (University of Oxford) for C. rodentium strain ICC169; and C. Mooser, R. De Guili, A. Printz and A. De Martin for technical support. Supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (146133 and 141918 to B.L.; and 151370 to E.S.), the Promedica Foundation (B.L.), Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (25460589, 16H05172 and 15H01153 to K.I.), the German Research Council (SFB974 and GRK1949 to P.A.L.) and the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (G.C.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, the decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Source data

Author Contributions

C.G.-C. and C.P.-S. designed the study, performed experiments and wrote the paper; L.O., Q.C., J.C., H.-W.C. and M.N. performed experiments; P.A.L., M.B.G. and K.D.M. discussed data; S.A., G.C. and K.I. generated and provided mice and discussed data; and E.S. and B.L. designed the study, discussed data and wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Cristina Gil-Cruz and Christian Perez-Shibayama: These authors contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Elke Scandella, Email: elke.scandella@kssg.ch.

Burkhard Ludewig, Email: burkhard.ludewig@kssg.ch.

References

- 1.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nature10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tumanov AV, et al. Lymphotoxin controls the IL-22 protection pathway in gut innate lymphoid cells during mucosal pathogen challenge. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macpherson AJ, Hapfelmeier S, McCoy KD. The armed truce between the intestinal microflora and host mucosal immunity. Semin. Immunol. 2007;19:57–58. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macpherson AJ, Geuking MB, Slack E, Hapfelmeier S, McCoy KD. The habitat, double life, citizenship, and forgetfulness of IgA. Immunol. Rev. 2012;245:132–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huntington ND, Carpentier S, Vivier E, Belz GT. Innate lymphoid cells: parallel checkpoints and coordinate interactions with T cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2016;38:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klose CS, et al. Differentiation of type 1 ILCs from a common progenitor to all helper-like innate lymphoid cell lineages. Cell. 2014;157:340–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nussbaum JC, et al. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 2013;502:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geiger TL, et al. Nfil3 is crucial for development of innate lymphoid cells and host protection against intestinal pathogens. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:1723–1731. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Randall TD, Carragher DM, Rangel-Moreno J. Development of secondary lymphoid organs. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:627–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Junt T, Scandella E, Ludewig B. Form follows function: lymphoid tissue microarchitecture in antimicrobial immune defence. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:764–775. doi: 10.1038/nri2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fletcher AL, Acton SE, Knoblich K. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15:350–361. doi: 10.1038/nri3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown FD, Turley SJ. Fibroblastic reticular cells: organization and regulation of the T lymphocyte life cycle. J. Immunol. 2015;194:1389–1394. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Link A, et al. Fibroblastic reticular cells in lymph nodes regulate the homeostasis of naive T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1255–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scandella E, et al. Restoration of lymphoid organ integrity through the interaction of lymphoid tissue-inducer cells with stroma of the T cell zone. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:667–675. doi: 10.1038/ni.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chai Q, et al. Maturation of lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells from myofibroblastic precursors is critical for antiviral immunity. Immunity. 2013;38:1013–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cremasco V, et al. B cell homeostasis and follicle confines are governed by fibroblastic reticular cells. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:973–981. doi: 10.1038/ni.2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mionnet C, et al. Identification of a new stromal cell type involved in the regulation of inflamed B cell follicles. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katakai T. Marginal reticular cells: a stromal subset directly descended from the lymphoid tissue organizer. Front. Immunol. 2012;3:200. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malhotra D, et al. Transcriptional profiling of stroma from inflamed and resting lymph nodes defines immunological hallmarks. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:499–510. doi: 10.1038/ni.2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cervantes-Barragan L, et al. Control of coronavirus infection through plasmacytoid dendritic-cell-derived type I interferon. Blood. 2007;109:1131–1137. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cervantes-Barragán L, et al. Type I IFN-mediated protection of macrophages and dendritic cells secures control of murine coronavirus infection. J. Immunol. 2009;182:1099–1106. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavi E, Gilden DH, Highkin MK, Weiss SR. The organ tropism of mouse hepatitis virus A59 in mice is dependent on dose and route of inoculation. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1986;36:130–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang PA, et al. Natural killer cell activation enhances immune pathology and promotes chronic infection by limiting CD8+ T-cell immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:1210–1215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118834109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Artis D, Spits H. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2015;517:293–301. doi: 10.1038/nature14189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tassi I, Klesney-Tait J, Colonna M. Dissecting natural killer cell activation pathways through analysis of genetic mutations in human and mouse. Immunol. Rev. 2006;214:92–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waldmann TA. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nri1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mortier E, et al. Macrophage- and dendritic-cell-derived interleukin-15 receptor alpha supports homeostasis of distinct CD8+ T cell subsets. Immunity. 2009;31:811–822. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castillo EF, Stonier SW, Frasca L, Schluns KS. Dendritic cells support the in vivo development and maintenance of NK cells via IL-15 trans-presentation. J. Immunol. 2009;183:4948–4956. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martín-Fontecha A, et al. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN-γ for TH1 priming. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:1260–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Jager PL, et al. The role of the Toll receptor pathway in susceptibility to inflammatory bowel diseases. Genes Immun. 2007;8:387–397. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Török HP, et al. Crohn's disease is associated with a toll-like receptor-9 polymorphism. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:365–366. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cario E. Innate immune signalling at intestinal mucosal surfaces: a fine line between host protection and destruction. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2008;24:725–732. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32830c4341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg R, Prescott N, Lord GM, MacDonald TT, Powell N. The unusual suspects--innate lymphoid cells as novel therapeutic targets in IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015;12:271–283. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klose CS, Diefenbach A. Transcription factors controlling innate lymphoid cell fate decisions. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014;381:215–255. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mortier E, Woo T, Advincula R, Gozalo S, Ma A. IL-15Rα chaperones IL-15 to stable dendritic cell membrane complexes that activate NK cells via trans presentation. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:1213–1225. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asquith M, Powrie F. An innately dangerous balancing act: intestinal homeostasis, inflammation, and colitis-associated cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1573–1577. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biron CA. Initial and innate responses to viral infections--pattern setting in immunity or disease. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1999;2:374–381. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucas M, Schachterle W, Oberle K, Aichele P, Diefenbach A. Dendritic cells prime natural killer cells by trans-presenting interleukin 15. Immunity. 2007;26:503–517. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baranek T, et al. Differential responses of immune cells to type I interferon contribute to host resistance to viral infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:571–584. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuchs A, et al. Intraepithelial type 1 innate lymphoid cells are a unique subset of IL-12- and IL-15-responsive IFN-γ-producing cells. Immunity. 2013;38:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Powell DW, Pinchuk IV, Saada JI, Chen X, Mifflin RC. Mesenchymal cells of the intestinal lamina propria. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2011;73:213–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Züst R, et al. Identification of coronavirus non-structural protein 1 as a major pathogenicity factor—implications for the rational design of live attenuated coronavirus vaccines. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e109. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghaem-Maghami M, et al. Intimin-specific immune responses prevent bacterial colonization by the attaching-effacing pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:5597–5605. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5597-5605.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(a) PP numbers in 8–10 week old Cre-negative littermate (Ctrl) and Myd88-cKO mice (n = 11 mice; each dot represents one individual mouse, bars indicate mean). (b–e) Composition of hematopoietic cells in PPs and mLNs as determined by flow cytometry; values indicate means ± s.e.m. of the indicated cell population (n = 8 mice, pooled data from 2 independent experiments). (f) Confocal microscopic analysis of Ccl19-Cre transgene activity (assessed as EYFP fluorescence) in interfollicular regions of PPs from 8-10 week old Ccl19EYFP and Ccl19EYFP Myd88-cKO mice; co-staining with FRC markers is indicated (scale bars = 10 μm); representative sections from one out of four mice. (g) Composition of the indicated EYFP+ fibroblastic stromal cell subsets in Ccl19EYFP and Ccl19EYFP Myd88-cKO mice as determined by the indicated marker combination (mean ± s.e.m., n = 8 mice, pooled from 2 independent experiments). Statistical analyses using Student’s t test did not reveal significant differences between Ccl19EYFP and Ccl19EYFP Myd88-cKO mice.

(a) Mice were infected with 5 × 104 PFU of MHV and viral titers were determined in Cre-negative littermate (Ctrl) and Myd88-cKO mice at day 6 post infection in spleen and liver (mean of log-transformed values ± s.e.m., n = 8 mice per group, pooled from 2 independent experiments). (b, c) ILC subset analysis in indicated organs. Representative plots show ILCs subsets in CD45+CD3− CD19−GR1− cells (Lin−). Bar graphs show frequencies (b) and absolute numbers (c) of ILC subsets in mLNs or PP on day 3 post infection (mean percentage or number ± s.e.m. of indicated cell populations, n ≥ 6 mice per group, pooled from 3 independent experiments). (d) Confirmation of ILC1 and NK cell identity using intracellular staining for EOMES; representative data from one out of three independent experiments. (e) Representative dot plots showing reduction of NK1.1+NKp46+ cells on day 3 of the infection following application of anti-NK1.1 antibody. (f) Frequencies of ILC subsets in PPs on day 3 post infection in anti-NK1.1 antibody-treated mice (mean percentage ± s.e.m. of CD45+ CD3−CD19−GR1− (Lin−) cells, n = 6 mice per group, pooled from 3 independent experiments). Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ND, non-detectable)

CD45− stromal cells were isolated from PPs of C57BL/6 or Myd88−/− mice by magnetic sorting. After 7 days in culture, expression of IL-15Rα on CD45− PDPN+ cells was determined by flow cytometry following exposure to IL-1β or the TLR7-ligands R848 or ssRNA 40 LyoVec at the indicated concentrations (ng/ml) (mean MFI ± s.e.m.). Pooled values from 3 independent experiments with 2 replicates per condition. Statistical analysis was performed using one way ANOVA with Tukey’s posttest (*, P < 0.05; **; P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

(a) Confocal microscopic analysis of Ccl19-Cre transgene activity (assessed as EYFP fluorescence) and distribution of CD4+ T cells and B220+ B cells in PPs of 8–10 week old Ccl19EYFP and Ccl19EYFP Il15-cKO mice (scale bar = 100 μm). (b) Abundance of indicated cell populations in PPs as determined by flow cytometry (mean ± s.e.m., n = 5 mice, pooled data from 3 independent experiments). (c,d) ILC subset analysis in mLNs of Cre-negative littermate (Ctrl) and Il15-cKO mice. (c) Plots from the CD45+Lin− cell fraction (mean ± s.e.m., n = 5 mice, pooled data from 3 independent experiments). (d) Absolute numbers of the indicated ILC populations in Cre-negative littermate (Ctrl) and Il15-cKO naive mice. (e) Flow cytometric analysis of EYFP reporter gene expression in bone marrow stromal cells from 8 wk old Ccl19EYFP mice (mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 mice) Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (***, P< 0.001)

(a,b) Representative flow cytometric analyses of IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin (PI) or MHV peptide M133 in PPs (a) and mLNs (b) on day 10 post infection. Values indicate percentage of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells. (c) CD4+ T cells producing IL-17 in PP and mLN following PI incubation. Values indicate mean percentage ± s.e.m., n = 8 mice, pooled from two independent experiments. (d) Viral titers on day 10 post infection in the indicated organs (mean ± s.e.m., n = 4 mice, pooled data from 2 independent experiments; ND, not detectable). (e) Ileal microbiota composition in naive and infected (day 10) Cre-negative littermate (Ctrl) and Myd88-cKO mice. Values indicate mean relative abundance ±s.e.m., n = 6 mice, one representative of two experiments of the indicated bacterial taxa. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; NS, not significant).

Supplementary Figures 1–5 and Supplementary Table 1 (PDF 1225 kb)