Highlights

-

•

We compared MERS-CoV RBD-induced immune responses via i.n. and s.c. routes.

-

•

I.n. induced comparable systemic humoral immune responses as s.c.

-

•

I.n. induced similar neutralization but more robust cellular responses than s.c.

-

•

I.n. elicited significantly higher local mucosal immune responses than s.c.

-

•

Has potential to be developed as an effective and safe MERS mucosal vaccine.

Keywords: MERS-CoV, Spike protein, Receptor-binding domain, Mucosal immune response, Systemic immune response, Neutralizing antibody

Abstract

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was originally identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012. It has caused MERS outbreaks with high mortality in the Middle East and Europe, raising a serious concern about its pandemic potential. Therefore, development of effective vaccines is crucial for preventing its further spread and future pandemic. Our previous study has shown that subcutaneous (s.c.) vaccination of a recombinant protein containing receptor-binding domain (RBD) of MERS-CoV S fused with Fc of human IgG (RBD-Fc) induced strong systemic neutralizing antibody responses in vaccinated mice. Here, we compared local and systemic immune responses induced by RBD-Fc via intranasal (i.n.) and s.c. immunization pathways. We found that i.n. vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc induced systemic humoral immune responses comparable to those induced by s.c. vaccination, including neutralizing antibodies, but more robust systemic cellular immune responses and significantly higher local mucosal immune responses in mouse lungs. This study suggests the potential of developing MERS-CoV RBD protein into an effective and safe mucosal candidate vaccine for prevention of respiratory tract infections caused by MERS-CoV.

1. Introduction

The recently emerged Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus (MERS-CoV) has caused a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-like disease with high case-fatality rate (CFR) [1], [2], [3]. As of December 27, 2013, a total of 170 laboratory-confirmed cases of infection with MERS-CoV, including 72 deaths, have been reported (http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_12_27/en/index.html). The continuous threat of MERS-CoV calls for the development of effective vaccines.

Unlike SARS-CoV, the causative agent of SARS, which uses human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as its functional receptor [4], MERS-CoV utilizes a novel coronavirus receptor, human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4, also known as CD26) for viral entry into the target cells [5], [6]. Different from SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV has a broader tissue tropism capable of infecting a variety of human and non-human cell types, including primate, porcine, and bat cells, and it maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines [7], [8]. Nevertheless, considering the similarity between MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, which both belong to the genus betacoronavirus [1], the approaches for the development of effective SARS vaccines are expected to be applicable to MERS vaccine development.

Previous studies on SARS have revealed that systemic humoral and cellular immune responses play important roles in the prevention of viral infection based on the production of high neutralizing antibodies and T cell immune responses [9], [10], [11]. In addition, mucosal immune response represented by secretory IgA is also crucial in the clearance of infected virus [12], [13]. The studies from SARS suggested that systemic humoral, cellular, and local mucosal immune responses will also be important in the prevention of MERS infection.

Because it can induce highly potent neutralizing antibodies and protection against virus infection, the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV spike (S) protein has been shown to be an attractive target for developing vaccines against SARS [10], [12], [14]. Similar to the RBD of SARS-CoV S protein, recent studies have shown that the RBD of MERS-CoV S protein also mediates virus binding to its receptor DPP4 [15], [16], [17], [18]. Thus, it is plausible that the RBD of MERS-CoV could be a comparably effective vaccine target.

Fc of human IgG, an immune enhancer, has been used as an important fusion tag capable of co-expressing with viral proteins to promote protein expression and purification, and improve the immunogenicity of the fusion proteins [19]. Our previous studies have shown that a recombinant SARS-CoV RBD protein fused with human Fc induced highly potent immune responses that completely protected vaccinated mice against SARS-CoV challenge [20], [21]. We have also demonstrated that recombinant Fc fusion proteins containing conserved sequences of hemagglutinin 1 (HA1) of H5N1 influenza virus elicited stronger neutralizing antibody responses than those without fusion with Fc that cross-protected mice from divergent strains of H5N1 virus challenge [22], confirming the ability of Fc in the enhancement of immunogenicity of the fusion proteins. The potential mechanism may be associated with its ability to promote correct folding of the fusion proteins, and allow the proteins binding to Fc receptor (FcR)-containing antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [23], [24]. Notably, the immunogenicity of human Fc region in mice has no detrimental effect on the immunogenicity of the specific antigen in the fusion proteins, as evidenced by the fact that H5N1 HA1 or MERS-CoV RBD proteins fused with human IgG Fc could elicit high titers of H5N1 influenza virus HA1 or MERS-CoV S1-specific antibody responses, respectively, in vaccinated mice [22], [25].

We thus constructed and expressed a recombinant protein containing RBD (residues 377–662) of MERS-CoV S protein fused with Fc of human IgG (S-RBD-Fc, hereinafter named RBD-Fc), and demonstrated in previous study that this protein induced significant antibody responses with neutralizing activity through the subcutaneous (s.c.) vaccination pathway [18]. To further evaluate the ability of this protein to elicit immune responses via the intranasal (i.n.) route, we compared in the present study the systemic and mucosal immune responses induced by the i.n. and s.c. vaccination pathways and emphasized the importance of developing i.n.-based mucosal vaccines for the prevention of MERS infection.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines and animals

HEK293T cells for expression of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Female BALB/c mice aged 4–6 weeks were used for the study. Animals were housed in the animal facility of New York Blood Center. The animal studies were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The animal protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the New York Blood Center (Permit Number: 194.14).

2.2. Construction and expression of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc recombinant protein

The construction, expression and purification of recombinant MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein were done as previously described [18]. Briefly, genes encoding RBD protein (residues 377–662) of MERS-CoV S were amplified by PCR using synthesized codon-optimized MERS-CoV S sequences (GenBank accession no. AFS88936.1) as the template and fused to the Fc of human IgG using pFUSE-hIgG1-Fc2 expression vector (hereinafter named Fc, InvivoGen, San Diego, CA). The MERS-CoV S1 (residues 18–725) plus 6× Histidine (His) was amplified as above and inserted into the pJW4303 expression vector (Jiangsu Taizhou Haiyuan Protein Biotech, Co., Ltd., China). The proteins were expressed in HEK293T cell culture supernatant and purified by protein A affinity chromatography (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) (for MERS-CoV RBD-Fc) or Ni-NTA Superflow (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) (for MERS-CoV S1), according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

2.3. Mouse vaccination and sample collection

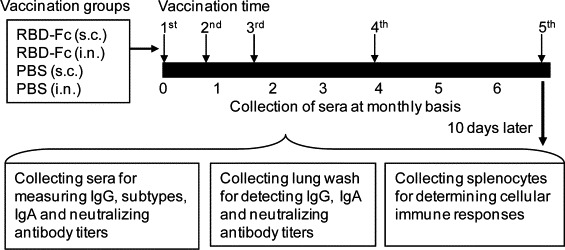

This was done using previously described immunization protocols with some modifications [22], [26]. Briefly, mice were prime-vaccinated, either s.c. with RBD-Fc (10 μg/mouse) plus adjuvant (Montanide ISA51, Seppic, Fairfield, NJ) (200 μl/mouse) or i.n. with RBD-Fc (10 μg/mouse) plus adjuvant (Poly(I:C), InvivoGen) (20 μl/mouse) after mice were anesthetized with isoflurane. Vaccinated mice were initially boosted twice at 21 and 42 days after the first vaccination and further boosted at the end of 3 and 6 months. Additionally, two groups of mice vaccinated with the same doses of PBS plus adjuvant (ISA51 for s.c. or Poly(I:C) for i.n.) were used as the negative controls. Mouse sera were collected on a monthly basis for up to 6 months, and lung wash and splenocytes were collected 10 days post-last vaccination (Fig. 1 ). Collected samples were detected for humoral systemic IgG antibody response and subtypes, local mucosal IgA antibody response, neutralizing antibodies, as well as cellular immune responses.

Fig. 1.

Mouse immunization, sample collection and immune response detection. Four groups of mice (5 mice/group) were respectively s.c. or i.n. prime-vaccinated with MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein plus adjuvant as the vaccine groups, or with PBS plus adjuvant as their respective controls. Mice were initially boosted twice at 21 and 42 days and further boosted at the end of the 3rd and 6th months with the same immunogens and vaccination routes, and sera were collected on a monthly basis. Ten days post-last vaccination, mouse sera and lung wash were collected to detect IgG, subtypes and IgA antibodies by ELISA, or neutralizing antibodies by neutralization assay. Mouse splenocytes collected at 10 days post-last vaccination were detected for cellular immune responses by flow cytometric analysis.

2.4. ELISA

MERS-CoV S-RBD-specific IgG, subtypes and IgA antibody responses were tested by ELISA in collected mouse sera and lung wash using our previously described protocols [12], [22]. Briefly, serially diluted mouse sera or lung flush were added to 96-well microtiter plates precoated with MERS-CoV RBD-Fc or MERS-CoV S1 protein, respectively. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, followed by four washes with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST). Bound antibodies were then reacted with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:3000, GE Healthcare), IgG1 (1:2000), IgG2a (1:5000), IgG3 (1:2000), or IgA (1:2000) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37 °C for 1 h. After four washes, the substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (Invitrogen) was added to the plates, and the reaction was stopped by adding 1 N H2SO4. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured by ELISA plate reader (Tecan, San Jose, CA).

2.5. Intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry analysis

T cell responses in immunized mice were detected by intracellular cytokine staining followed by flow cytometry analysis as previously described [12], [26]. Briefly, splenocytes (2 × 106) were stimulated with or without MERS-CoV S1 protein or SARS-CoV RBD protein (as the negative control) for 3 days at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in the presence of GolgiPlug™ containing brefeldin A (1 μl/ml; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 20 ng/ml) and ionomycin (2 μg/ml) (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were used as positive controls. The cells were fixed using a Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Plus Kit in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol (BD Biosciences) and then stained directly with conjugated anti-mouse-CD4 (APC), anti-mouse-CD8 (P-Cy5-5), anti-mouse-IL-2 (FITC), and anti-mouse-IFN-γ (PE) (BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4 °C. Appropriate isotype-matched controls for cytokines were included in each staining. The stained cells were analyzed using flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences), and the data were evaluated by FACSDiva software v.6.1.2 (BD Biosciences).

2.6. Neutralization assay

Titers of neutralizing antibodies in immunized mouse sera and lung wash were detected as previously described with some modifications [18], [25], [27]. Briefly, serum samples were diluted at serial 2-fold in 96-well tissue culture plates and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with ∼100 infectious MERS-CoV/Erasmus Medical Center (EMC)-2012 in each well before transferring the resulting mixtures to duplicate wells of confluent Vero E6 cells. After 72 h of incubation, when the virus control wells exhibited advanced virus-induced cytopathic effect (CPE), the neutralizing capacities of individual serum or lung wash specimens were assessed by determining the presence or absence of CPE. Neutralizing antibody titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of serum or lung wash that completely (100%) inhibited virus-induced CPE in at least 50% of the wells.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean with standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance between different vaccination groups was calculated by Student's t test using SPSS 19.0 statistical software. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Intranasal vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc induced systemic humoral IgG antibody response similar to that of s.c. vaccination in mouse sera and lungs

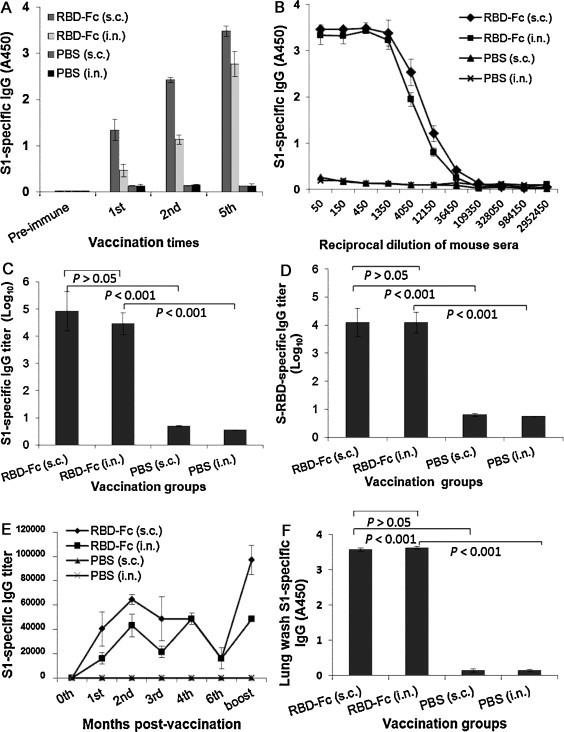

To evaluate the ability of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc to induce systemic humoral immune responses via the i.n. route, as well as compare the differences between immune responses induced via both s.c. and i.n. routes, we collected mouse sera at different time points and used ELISA to detect IgG antibodies specific to MERS-CoV S1 or S-RBD protein. As shown in Fig. 2A, a single prime dose i.n. vaccination of RBD-Fc did not elicit significant IgG antibody response, while MERS-CoV S1-specific IgG antibodies rapidly increased to a higher level post-last vaccination. In comparison, a single prime dose s.c. vaccination of RBD-Fc induced a relatively higher level of specific IgG antibody response. Although s.c. boost vaccination of the protein elicited increasing levels of IgG antibodies after the last vaccination, the antibody titer (1:3000) was similar to that induced via i.n. vaccination. Sera from s.c. and i.n. vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc could bind specifically to MERS-CoV S1 protein without fusion with Fc (Fig. 2B), with the endpoint IgG antibody titers reaching similar levels at 1:8.3 × 104 for s.c., or 1:4.0 × 104 for i.n., respectively (Fig. 2C), post-last vaccination. As expected, MERS-CoV RBD-Fc s.c.- and i.n.-vaccinated mouse sera were both able to bind significantly to MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein (Fig. 2D). No significant difference of IgG production was seen between s.c. and i.n. vaccination groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2C and D).

Fig. 2.

Detection of total IgG antibody responses by ELISA in vaccinated mouse sera and lung wash. (A) Reactivity of serum IgG antibodies specific to MERS-CoV S1 protein. The MERS S1-specific IgG was detected using sera (1:3000) from mice before (pre-immune) and 10 days post-1st, -2nd, and -last vaccination. The data are presented as mean A450 ± standard deviation (SD) of five mice per group. (B) Ability of IgG binding to MERS-CoV S1 protein was detected using sera from 10 days post-last vaccination. The data are presented as mean A450 ± SD of five mice per group at various dilution points. MERS-CoV S1- (C) or S-RBD- (D) specific IgG endpoint titers were detected using sera from 10 days post-last vaccination. The data are presented as geometric mean titer (GMT) ± SD of five mice per group. (E) Detection of long-term antibody responses using sera collected at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 months and 10 days post-last vaccination. The data are presented as mean (IgG endpoint titers) ± SD of five mice per group. (F) Reactivity of lung wash IgG antibodies specific to MERS-CoV S1 was detected using mouse lung wash (1:1000) 10 days post-last vaccination. The data are presented as mean A450 ± SD of five mice per group.

We then assessed the capability of RBD-Fc protein to induce long-term antibody responses and compared the results between i.n. and s.c. vaccinations. As expected, elevated IgG specific to the S1 of MERS-CoV was detected in i.n.-vaccinated mouse sera, quickly reaching a higher level at the 2nd month. Although IgG antibody titers induced by the i.n. route decreased to a lower level at the 3rd month, they could rapidly increase to a level equal to that attained by the s.c. route at the 4th month after further boost at the end of the 3rd month. For both i.n. and s.c. routes, the 5th vaccination at the end of the 6th month helped increase IgG antibody to the highest titer, suggesting that the i.n. injection of RBD-Fc was, much like injection of RBD-Fc by the s.c. pathway, able to stimulate long-term humoral immune responses in vaccinated mice and that multiple boost vaccinations are required to maintain strong antibody responses (Fig. 2E). In the collected mouse lung wash, both s.c. and i.n. vaccinations of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein elicited similar level of MERS-CoV S1-specific IgG antibodies (Fig. 2F), while immunizations from both s.c. and i.n. PBS control groups only induced background levels of IgG antibody responses (Fig. 2).

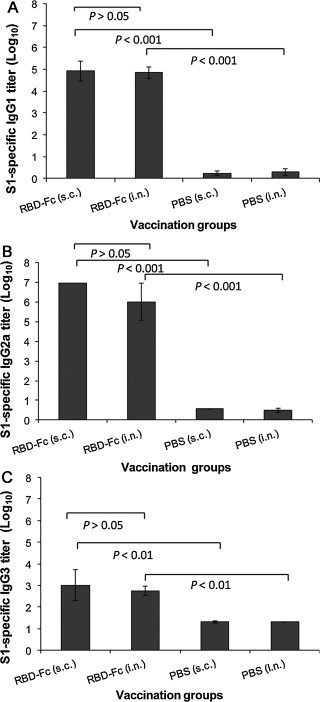

Further evaluation of serum IgG subtype antibody responses revealed that i.n. vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc elicited MERS-CoV S1-specific IgG1 (Th2-associated), IgG2a (Th1-associated) and IgG3 antibody responses similar to that induced by s.c. vaccination (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3 ). It should be noted that the values of IgG2a (Th1-associated) antibody against MERS-CoV S1 protein were relatively higher than those of IgG1 (Th2-associated) antibody for both i.n. and s.c. vaccinations, suggesting that MERS-CoV RBD-Fc induced a slightly biased Th1-associated antibody response. Only background levels of serum IgG1, IgG2a and IgG3 antibodies against the test antigen were detectable in s.c. and i.n. PBS control groups (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Detection of IgG subtypes by ELISA in vaccinated mouse sera. MERS-CoV S1-specific IgG1 (A), IgG2a (B) and IgG3 (C) antibodies induced by i.n. or s.c. vaccination were detected using sera from 10 days post-last vaccination. The endpoint titer of each sample was determined as the highest dilution that yielded an OD450 nm value greater than twice that of similarly diluted serum sample collected pre-immunization with an optical density of 0.15. The data are presented as GMT ± SD of five mice per group.

The above results suggest that mice i.n. vaccinated with MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein induced strong systemic humoral IgG antibody responses in sera and lungs, reflecting results similar to the s.c. vaccinated mice.

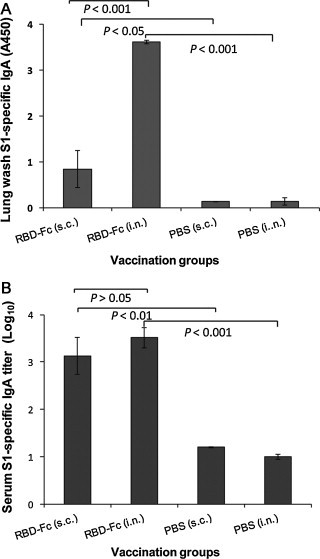

3.2. Intranasal vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc induced significantly higher local mucosal immune responses in mouse lungs compared to s.c. vaccination

To assess the ability of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein to induce local mucosal immune responses, mucosal IgA antibody response was detected by ELISA in the collected mouse lung wash. IgA from vaccinated mouse sera was included as the control. As shown in Fig. 4 , i.n. vaccination of RBD-Fc elicited strong MERS-CoV S1-specific IgA antibody response in lung wash, which was significantly higher than that induced by RBD-Fc s.c. immunization (P < 0.001). These data suggest that vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein by the i.n., but not by the s.c. route, induced strong local mucosal immune response, as represented by a high level of mucosal IgA. In particular, the lung wash from the mice i.n.-vaccinated with the test protein contained MERS-CoV S1-specific IgA antibody, which was still highly detectable, even after 1:1000 dilution of the test samples. However, only background level of IgA was detected from mouse lung wash samples of s.c. and i.n. PBS control groups (Fig. 4). Additionally, it was noticed that RBD-Fc-vaccinated mouse sera contained IgA antibody and that such samples maintained a slightly higher titer by the i.n. route compared to the s.c. route (P > 0.05). This evidence suggests that i.n. vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc was able to induce a stronger local mucosal immune response than that achieved by the s.c. route.

Fig. 4.

Detection of IgA antibody responses by ELISA in vaccinated mouse lung wash and sera. The MERS-CoV S1-specific IgA antibodies induced by i.n. or s.c. vaccination were detected using mouse lung wash (1:1000) (A) or serial diluted sera (B) 10 days post-last vaccination. The data from lung wash are presented as mean A450 ± SD of five mice per group. The endpoint titer of each serum sample was determined as the highest dilution that yielded an OD450 nm value greater than twice that of similarly diluted serum sample collected pre-immunization with an optical density of 0.15. The data from serum samples are presented as GMT ± SD of five mice per group.

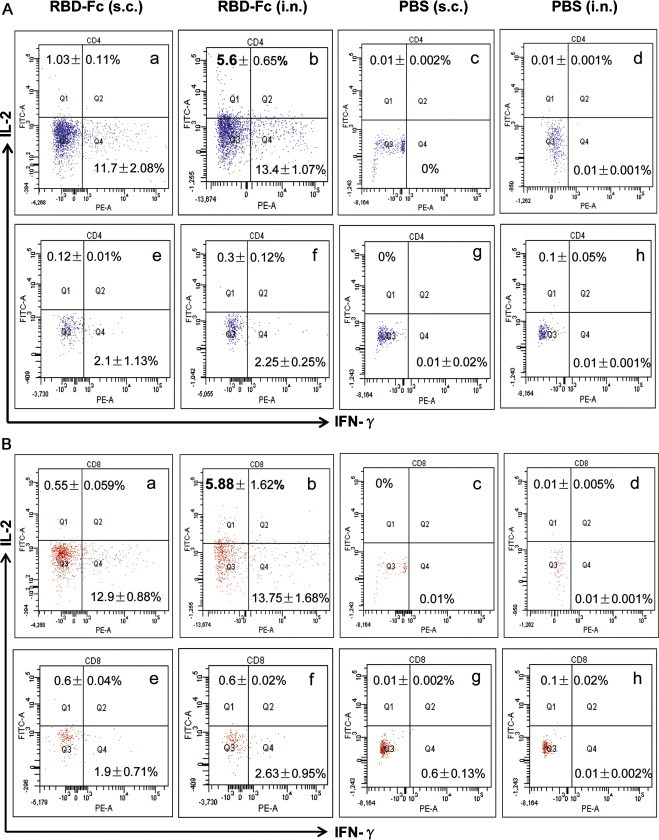

3.3. Intranasal vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc induced more robust cellular immune responses than s.c. vaccination in mouse spleens

To evaluate and compare cellular immune responses potentially induced by i.n. and s.c. vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc, IL-2- or IFN-γ-producing T cell responses were detected in the splenocytes of immunized mice by cell surface marker and intracellular cytokine staining, followed by flow cytometric analysis. As shown in Fig. 5 , i.n. and s.c. vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein was capable of inducing substantial T cell immune responses, as represented by the high frequency of IL-2- and IFN-γ-producing T cells after stimulation of splenocytes with MERS-CoV S1 protein. In particular, i.n. vaccination of RBD-Fc elicited a significantly higher frequency of MERS-CoV S1-specific IL-2-producing T cells and a slightly higher level of IFN-γ-producing T cells in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations, as compared with those from s.c. vaccination of the same protein. Importantly, SARS-CoV RBD protein control failed to stimulate the splenocytes derived from MERS-CoV RBD-Fc-vaccinated mice, irrespective the routes of immunization. Also, mice immunized via either i.n. or s.c. route in the PBS control group did not reveal any MERS-CoV S1-specific IL-2- or IFN-γ-producing T cell responses. Taken together, these results suggest that vaccination via the i.n. route with MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein has the ability to elicit stronger cellular responses than the s.c. route, as represented by IL-2- and IFN-γ-producing T cells.

Fig. 5.

Detection of cellular immune responses by flow cytometric analysis in spleens of vaccinated mice 10 days post-last vaccination. MERS-CoV S1-specific T cell responses were detected for frequencies of IL-2- and IFN-γ-producing CD4+ splenocytes (A) and CD8+ splenocytes (B) by cell surface marker, followed by intracellular cytokine staining using flow cytometric analysis. Splenocytes from MERS-CoV RBD-Fc-vaccinated mice were incubated with recombinant MERS-CoV S1 protein (panels a and b in A and B), or SARS-CoV RBD protein (as the control) (panels e and f in A and B). Splenocytes of mice from the PBS control were also stimulated with MERS-CoV S1 (panels c and d in A and B) or SARS-CoV RBD protein (panels g and h in A and B). Frequencies of IL-2- and IFN-γ-producing cells were expressed as percentages of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. The data in the upper left or the bottom right corner of each graph represent the frequencies of IL-2- or IFN-γ-producing CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. The samples were tested in triplicate and presented as mean ± SD (five mice per group). The numbers in bold indicate significant difference between corresponding s.c. and i.n. vaccination groups. The experiments were repeated for three times, and similar results were obtained.

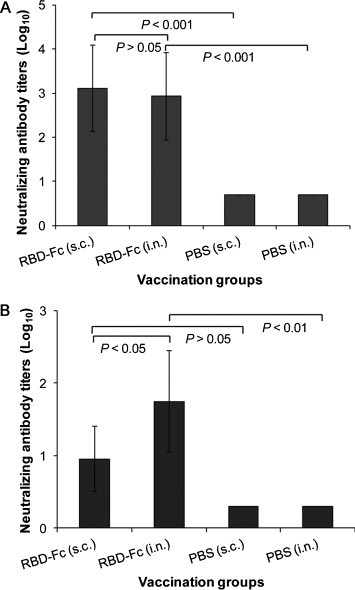

3.4. Intranasal vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc elicited a considerable neutralizing antibody titer in mouse sera and lung wash

To investigate the ability of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc to induce neutralizing antibodies via the i.n. route, sera containing the highest IgG antibody (e.g., 10 days post-5th vaccination) and lung wash were detected for the neutralization of MERS-CoV infection in Vero E6 cells. Data from Fig. 6A demonstrated that both i.n. and s.c. vaccinations of RBD-Fc could induce equally strong neutralizing antibody responses against MERS-CoV in immunized mouse sera (P > 0.05). Notably, i.n. vaccination of RBD-Fc induced a significantly higher level of neutralizing antibody in the collected mouse lung wash than s.c. vaccination of RBD-Fc, indicating that i.n. immunization with RBD-Fc is able to induce stronger mucosal immune responses with neutralizing activity (Fig. 6B). The s.c. and i.n. PBS control groups only induced a background level of neutralizing antibody titers in both vaccinated mouse sera and lung wash. These results suggest that RBD-Fc has the potential for development as a mucosal vaccine for i.n. vaccination to prevent MERS-CoV infection.

Fig. 6.

Detection of neutralizing antibody titers by neutralization assay in vaccinated mouse samples. Sera (A) and lung wash (1:1000 dilution in PBS during collection) (B) from i.n. or s.c. vaccination groups were collected at 10 days post-last vaccination and analyzed for neutralization of MERS-CoV infection in Vero E6 cells. Neutralizing antibody titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of serum that completely inhibited virus-induced CPE in at least 50% of the wells (NT50), and are presented as GMT ± SD from five mice per group.

4. Discussion

MERS, a novel emerging infectious respiratory tract disease, was first identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012 and then spread to other countries in the Middle East and Europe [1], [3], [28], [29]. With increasing numbers of infections and deaths from the disease, development of effective and safe vaccines, including one capable of inducing mucosal immune responses to the sites of virus infection, will be crucial to prevent further spread of MERS-CoV and its potential pandemic. Using reverse genetics system, a full-length infectious cDNA clone of MERS-CoV genome has been successfully constructed into a bacterial artificial chromosome, providing the possibility of developing attenuated viruses as MERS mucosal vaccine candidates [30].

Previous studies on SARS have revealed that vaccines targeting the RBD of SARS-CoV S protein are effective in inducing potent systemic immune responses with neutralizing activity that completely protects vaccinated animals from virus challenge [10], [20], [31]. In addition, intranasal vaccination of a SARS-CoV RBD-based vaccine was able to elicit strong mucosal immune responses, providing long-term protection against SARS-CoV infection [12]. These studies indicated that the S protein, particularly RBD, of SARS-CoV is an important target for SARS vaccine development and that mucosal immune response, in addition to systemic immunity, also plays a significant role in the prevention of SARS-CoV infection. Experience based on SARS studies suggests that the S protein, including RBD, of MERS-CoV, another coronavirus in the same genus of betacoronavirus [1], [32], [33], could be a promising target for the development of vaccines against MERS.

As expected, recent studies have shown that a recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) expressing full-length S protein of MERS-CoV (MVA-MERS-S) produced high levels of serum antibodies in vaccinated mice that neutralized MERS-CoV infection [34]. Our previous study also showed that s.c. vaccination of a recombinant vaccine targeting the RBD (residues 377–662) of MERS-CoV S fused to Fc of human IgG (RBD-Fc) protein elicited humoral IgG antibody responses with favorable neutralizing activity, and that a truncated Fc-fused RBD protein of MERS-CoV S (S377-588-Fc) induced strong neutralizing antibody responses in vaccinated mice [18], [25], suggesting that the RBD of MERS-CoV is indeed a promising vaccine target. In this study, we compared the capability of RBD-Fc protein to induce systemic humoral and cellular immune responses, and local mucosal immune responses via i.n. and s.c. vaccinations. As for the adjuvant, we used Poly(I:C) for i.n. vaccination and Montanide ISA 51 for s.c. immunization. This is because that Poly(I:C), a synthetic double-stranded RNA polymer, has been previously reported as an efficient mucosal adjuvant for influenza vaccines [35], [36], and Montanide ISA 51, a mineral oil-based adjuvant, has been shown in our previous studies to be effective in inducing strong influenza HA or MERS-CoV S-RBD-specific humoral immune responses with neutralizing activity via the s.c. route [22], [25].

Interestingly, results from this study demonstrated that systemic humoral IgG antibody responses and their subtypes induced by the i.n. vaccination pathway were comparable to those induced by the s.c. pathway in the collected mouse sera and lung wash that are specific to S1 and RBD of MERS-CoV. More specifically, both vaccination pathways induced a relatively higher level of Th1-associated IgG2a than Th2-associated IgG1. It should be noted that similar levels of IgG3, which is considered important in antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and virus neutralization [37], were detectable in vaccinated mouse sera via both i.n. and s.c. routes. These data suggested that MERS-CoV RBD-Fc immunization by the i.n. route was capable of eliciting similar, if not greater, systemic humoral antibody responses than those elicited by the s.c. pathway in vaccinated mice. Significantly, a similarly high titers of serum neutralizing antibodies were raised in mice vaccinated with 5 doses of RBD-Fc protein via both i.n. and s.c. routes (P > 0.05, Fig. 6), about 4-fold higher than that attained from 2 doses of s.c. vaccination of the same protein [18]. That the increase of vaccination doses leads to improved neutralizing antibody titers indicates the need for multiple vaccinations of RBD protein containing residues 377–662 of MERS-CoV S to induce stronger neutralizing antibody responses that can be maintained up to 6 months.

MERS-CoV infects humans through the respiratory tract, presenting severe acute respiratory syndromes like SARS [38], [39]. Accordingly, vaccines capable of inducing strong local mucosal immunity represented by secretory IgA would be helpful in preventing MERS-CoV infection. Our data indicated that MERS-CoV S1-specific IgA antibody responses with neutralizing activity in vaccinated mouse lungs were elicited by i.n. vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein, which were significantly higher than those induced by s.c. vaccination of the same protein, confirming the ability of RBD-Fc to induce strong local mucosal immunity via the i.n. route. Our previous studies on SARS-CoV RBD-based vaccines demonstrated that induction of mucosal IgA via the i.n. pathway played an important role in preventing SARS-CoV infection. We have previously demonstrated that in the presence of high titer of mucosal IgA, mice with serum neutralizing antibody as low as 1:190 can still be fully protected from SARS-CoV challenge replication [12]. It is thus reasonable to prospect that high titers of local mucosal neutralizing IgA, and serum neutralizing antibodies induced by i.n. vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc protein, as shown in this study, will effectively inhibit MERS-CoV infection and protect the animals from MERS-CoV challenge.

Previous reports from SARS studies revealed that SARS-CoV S protein-specific CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cell immune responses could be induced in vaccinated animals and that IFN-γ-producing memory CD8+ T cells, as well as IFN-γ-, IL-2- or TNF-α-producing memory CD4+ T cells, were still detectable from recovered patients 4 years after SARS infection [26], [40], [41], [42], suggesting that cellular immune responses also play a role in the prevention of viral infection. Similarly, when compared to the s.c. route adjuvanted with Montanide ISA 51, we found that MERS-CoV RBD-Fc was able to induce a higher frequency of MERS-CoV S1-specific, IL-2-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in vaccinated mouse spleens through the i.n. route in the presence of Poly(I:C) adjuvant. The higher cellular immune responses induced by RBD-Fc vaccination through the i.n. route, compared to the s.c. route, are possibly because of different adjuvants used in the corresponding pathway. It was reported that that s.c.-vaccination of a cancer vaccine formulated with Montanide ISA 51 and Picibanil OK-432 adjuvants is able to induce antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in majority of the vaccinated patients [43], while i.n. administration of Yersinia pestis LcrV protein fused to anti-DEC antibody adjuvanted with Poly(I:C) induced high frequencies of IFN-γ secreting CD4+ T cells as well as IFN-γ/TNF-α/IL-2-secreting polyfunctional CD4+ T cells in the airway and lung of vaccinated mice [44]. Thus, further optimization of the MERS-CoV candidate vaccines in the presence of different adjuvants is essential to evaluate the roles of cellular immune response, in addition to humoral and mucosal immunity, in protecting against MERS-CoV infection once an animal challenge model for MERS becomes available.

To summarize, we compared the systemic humoral and cellular immune responses, and local mucosal immune responses via i.n. and s.c. vaccination of a recombinant RBD protein containing residues 377–662 of MERS-CoV S fused with Fc of human IgG (RBD-Fc). We found that i.n. vaccination of MERS-CoV RBD-Fc induced systemic humoral immune responses, including neutralizing antibodies, comparable to those induced by s.c. vaccination, but more robust systemic cellular immune responses and significantly higher local (lung) mucosal immune responses in the vaccinated mice. Therefore, our results suggest the possibility of developing this protein into an effective and safe mucosal MERS vaccine for preventing MERS-CoV infection and stopping further spread of MERS-CoV.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the grants from the National Institute of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (AI109094), an intramural fund of the New York Blood Center (NYB000068), and the National 973 Program of China (2011CB504706 and 2012CB519001).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Lanying Du, Email: ldu@nybloodcenter.org.

Shibo Jiang, Email: sjiang@nybloodcenter.org.

References

- 1.Zaki A.M., van B.S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Memish Z.A., Zumla A.I., Assiri A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections in health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:884–886. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1308698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assiri A., McGeer A., Perl T.M., Price C.S., Al Rabeeah A.A., Cummings D.A. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li W., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S.K., Berne M.A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raj V.S., Mou H., Smits S.L., Dekkers D.H., Muller M.A., Dijkman R. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature. 2013;495:251–254. doi: 10.1038/nature12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gierer S., Bertram S., Kaup F., Wrensch F., Heurich A., Kramer-Kuhl A. The spike protein of the emerging betacoronavirus EMC uses a novel coronavirus receptor for entry, can be activated by TMPRSS2, and is targeted by neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2013;87:5502–5511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00128-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller M.A., Raj V.S., Muth D., Meyer B., Kallies S., Smits S.L. Human coronavirus EMC does not require the SARS-coronavirus receptor and maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines. MBio. 2012:3. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00515-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan J.F., Chan K.H., Choi G.K., To K.K., Tse H., Cai J.P. Differential cell line susceptibility to the emerging novel human betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012: implications for disease pathogenesis and clinical manifestation. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1743–1752. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai B., Lu X., Meng J., Hu Q., Mao P., Lu B. Vaccination of mice with recombinant baculovirus expressing spike or nucleocapsid protein of SARS-like coronavirus generates humoral and cellular immune responses. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:868–875. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du L., Zhao G., Chan C.C., Sun S., Chen M., Liu Z. Recombinant receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV spike protein expressed in mammalian, insect and E. coli cells elicits potent neutralizing antibody and protective immunity. Virology. 2009;393:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Y., Lu H., Siddiqui P., Zhou Y., Jiang S. Receptor-binding domain of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein contains multiple conformation-dependent epitopes that induce highly potent neutralizing antibodies. J Immunol. 2005;174:4908–4915. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du L., Zhao G., Lin Y., Sui H., Chan C., Ma S. Intranasal vaccination of recombinant adeno-associated virus encoding receptor-binding domain of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) spike protein induces strong mucosal immune responses and provides long-term protection against SARS-CoV infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:948–956. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J.S., Poo H., Han D.P., Hong S.P., Kim K., Cho M.W. Mucosal immunization with surface-displayed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein on Lactobacillus casei induces neutralizing antibodies in mice. J Virol. 2006;80:4079–4087. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.4079-4087.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du L., He Y., Zhou Y., Liu S., Zheng B.J., Jiang S. The spike protein of SARS-CoV – a target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:226–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y., Rajashankar K.R., Yang Y., Agnihothram S.S., Liu C., Lin Y.L. Crystal structure of the receptor-binding domain from newly emerged Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2013;87:10777–10783. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01756-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mou H., Raj V.S., van Kuppeveld F.J., Rottier P.J., Haagmans B.L., Bosch B.J. The receptor binding domain of the new Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus maps to a 231-residue region in the spike protein that efficiently elicits neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2013;87:9379–9383. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01277-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang N., Shi X., Jiang L., Zhang S., Wang D., Tong P. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res. 2013;23:986–993. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du L., Zhao G., Kou Z., Ma C., Sun S., Poon V.K. Identification of a receptor-binding domain in the S protein of the novel human coronavirus Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an essential target for vaccine development. J Virol. 2013;87:9939–9942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01048-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y., Du L., Qiu H., Zhao G., Wang L., Zhou Y. A recombinant protein containing highly conserved hemagglutinin residues 81–122 of influenza H5N1 induces strong humoral and mucosal immune responses. Biosci Trends. 2013;7:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du L., Zhao G., He Y., Guo Y., Zheng B.J., Jiang S. Receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV spike protein induces long-term protective immunity in an animal model. Vaccine. 2007;25:2832–2838. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He Y., Zhou Y., Liu S., Kou Z., Li W., Farzan M. Receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV spike protein induces highly potent neutralizing antibodies: implication for developing subunit vaccine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:773–781. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du L., Zhao G., Sun S., Zhang X., Zhou X., Guo Y. A critical HA1 neutralizing domain of H5N1 influenza in an optimal conformation induces strong cross-protection. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martyn J.C., Cardin A.J., Wines B.D., Cendron A., Li S., Mackenzie J. Surface display of IgG Fc on baculovirus vectors enhances binding to antigen-presenting cells and cell lines expressing Fc receptors. Arch Virol. 2009;154:1129–1138. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen H., Xu X., Jones I.M. Immunogenicity of the outer domain of a HIV-1 clade C gp120. Retrovirology. 2007;4:33. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du L., Kou Z., Ma C., Tao X., Wang L., Zhao G. A truncated receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV spike protein potently inhibits MERS-CoV infection and induces strong neutralizing antibody responses: implication for developing therapeutics and vaccines. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e81587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du L., Zhao G., Lin Y., Chan C., He Y., Jiang S. Priming with rAAV encoding RBD of SARS-CoV S protein and boosting with RBD-specific peptides for T cell epitopes elevated humoral and cellular immune responses against SARS-CoV infection. Vaccine. 2008;26:1644–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao X., Hill T.E., Morimoto C., Peters C.J., Ksiazek T.G., Tseng C.T. Bilateral entry and release of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus induces profound apoptosis of human bronchial epithelial cells. J Virol. 2013;87:9953–9958. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01562-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cauchemez S., Van K.M., Riley S., Donnelly C., Fraser C., Ferguson N. Transmission scenarios for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and how to tell them apart. Euro Surveill. 2013:18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breban R., Riou J., Fontanet A. Interhuman transmissibility of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: estimation of pandemic risk. Lancet. 2013;382:694–699. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61492-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Almazan F., DeDiego M.L., Sola I., Zuniga S., Nieto-Torres J.L., Marquez-Jurado S. Engineering a replication-competent, propagation-defective Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus as a vaccine candidate. MBio. 2013;4:e00650–e713. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00650-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du L., Zhao G., Li L., He Y., Zhou Y., Zheng B.J. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV S protein receptor-binding domain stably expressed in CHO cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384:486–490. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan J.F., Li K.S., To K.K., Cheng V.C., Chen H., Yuen K.Y. Is the discovery of the novel human betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012 (HCoV-EMC) the beginning of another SARS-like pandemic? J Infect. 2012;65:477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van B.S., de G.M., Lauber C., Bestebroer T.M., Raj V.S., Zaki A.M. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. MBio. 2012;3:e00473-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00473-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song F., Fux R., Provacia L.B., Volz A., Eickmann M., Becker S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein delivered by modified vaccinia virus ankara efficiently induces virus-neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2013;87:11950–11954. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01672-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ichinohe T., Watanabe I., Ito S., Fujii H., Moriyama M., Tamura S. Synthetic double-stranded RNA poly(I:C) combined with mucosal vaccine protects against influenza virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:2910–2919. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2910-2919.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ichinohe T., Kawaguchi A., Tamura S., Takahashi H., Sawa H., Ninomiya A. Intranasal immunization with H5N1 vaccine plus Poly I:Poly C12U, a Toll-like receptor agonist, protects mice against homologous and heterologous virus challenge. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:1333–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frasca D., Diaz A., Romero M., Mendez N.V., Landin A.M., Blomberg B.B. Effects of age on H1N1-specific serum IgG1 and IgG3 levels evaluated during the 2011-2012 influenza vaccine season. Immun Ageing. 2013;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guery B., Poissy J., El M.L., Sejourne C., Ettahar N., Lemaire X. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet. 2013;381:2265–2272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drosten C., Seilmaier M., Corman V.M., Hartmann W., Scheible G., Sack S. Clinical features and virological analysis of a case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:745–751. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70154-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao K., Yang B., Xu Y., Wu C. CD8+ T cell response in HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice is elicited by epitopes from SARS-CoV S protein. Vaccine. 2010;28:6666–6674. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fan Y.Y., Huang Z.T., Li L., Wu M.H., Yu T., Koup R.A. Characterization of SARS-CoV-specific memory T cells from recovered individuals 4 years after infection. Arch Virol. 2009;154:1093–1099. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0409-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang J., Ma R., Wu C.Y. Immunization with SARS-CoV S DNA vaccine generates memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cell immune responses. Vaccine. 2006;24:4905–4913. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kakimi K., Isobe M., Uenaka A., Wada H., Sato E., Doki Y. A phase I study of vaccination with NY-ESO-1f peptide mixed with Picibanil OK-432 and Montanide ISA-51 in patients with cancers expressing the NY-ESO-1 antigen. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2836–2846. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Do Y., Didierlaurent A.M., Ryu S., Koh H., Park C.G., Park S. Induction of pulmonary mucosal immune responses with a protein vaccine targeted to the DEC-205/CD205 receptor. Vaccine. 2012;30:6359–6367. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]