Abstract

The recent discovery of the unique genome of influenza virus H17N10 in bats raises considerable doubt about the origin and evolution of influenza A viruses. It also identifies a neuraminidase (NA)-like protein, N10, that is highly divergent from the nine other well-established serotypes of influenza A NA (N1–N9). The structural elucidation and functional characterization of influenza NAs have illustrated the complexity of NA structures, thus raising a key question as to whether N10 has a special structure and function. Here the crystal structure of N10, derived from influenza virus A/little yellow-shouldered bat/Guatemala/153/2009 (H17N10), was solved at a resolution of 2.20 Å. Overall, the structure of N10 was found to be similar to that of the other known influenza NA structures. In vitro enzymatic assays demonstrated that N10 lacks canonical NA activity. A detailed structural analysis revealed dramatic alterations of the conserved active site residues that are unfavorable for the binding and cleavage of terminally linked sialic acid receptors. Furthermore, an unusual 150-loop (residues 147–152) was observed to participate in the intermolecular polar interactions between adjacent N10 molecules of the N10 tetramer. Our study of influenza N10 provides insight into the structure and function of the sialidase superfamily and sheds light on the molecular mechanism of bat influenza virus infection.

Keywords: enzymatic activity, crystallography

Influenza virus is one of the most common causes of human respiratory infections that result in high morbidity and mortality (1). Among the three types of influenza virus (A, B, and C), the influenza A viruses, particularly the pandemic 2009 H1N1 (pH1N1) and highly pathogenic H5N1, embody the significant threat of host switch events (2–6). The recently discovered influenza virus H17N10 (only the genome was identified) from bats has the potential to reassort with human influenza viruses (7), providing insight into the origin and evolution of influenza A viruses beyond the predominant hypothesis of waterfowls/shorebirds as the primary natural reservoir (8). The products of the eight gene segments of H17N10 are unique among all known influenza A viruses at the primary sequence level, however. Thus, the current lack of structural and functional characterization impedes our understanding of the biology of this unusual viral genome.

Before the discovery of the bat-derived influenza virus genome, the nine serotypes of influenza A virus neuraminidase (NA) could be classified into two groups according to their primary sequence: group 1, comprising N1, N4, N5, and N8, and group 2, comprising N2, N3, N6, N7, and N9 (9). Extensive structural and functional studies of group 2 influenza NAs have led to the development of NA as the most successful drug target against flu to date (10–16). The recent identification of group 1 NA structures, including H5N1 NA (17), pandemic 2009 H1N1 NA (09N1) (18), 1918 H1N1 NA (18N1) (19), N4 (17), N5 (20), and N8 (17), further illustrates the complexity of influenza NA structures and offers some ideas for the design of next-generation NA inhibitors (21, 22). However, the identification of N10 revealed an NA-like protein that is significantly divergent from other influenza NAs (7), and thus whether N10 has special structural and/or functional features remains unknown.

Here we report the crystal structure of the bat-derived influenza virus N10. Our findings demonstrate that N10 has a canonical sialidase fold but lacks sialidase activity. The dramatic changes in the conserved active site residues relative to canonical influenza NAs account for both unfavorable binding and cleavage of the sialidase substrate. Moreover, a unique 150-loop (residues 147–152) is directly involved in the intermolecular interaction of monomers in the N10 tetramer.

Results

Overall Structure.

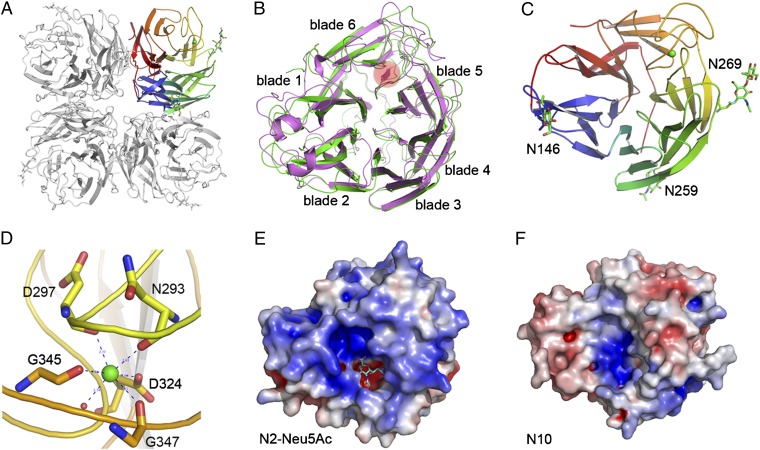

The ectodomain of N10 from influenza virus A/little yellow-shouldered bat/Guatemala/153/2009 (H17N10) was cloned and expressed using a baculovirus expression system based on a previously reported method (18, 19, 23) with slight modifications. The crystal structure of N10 was solved at a resolution of 2.20 Å and exhibited an overall structure similar to that of canonical influenza virus NAs. N10 subunits were assembled into a box-shaped tetramer, with each monomer containing a propeller-like arrangement of six-bladed β sheets (Fig. 1A). Comprehensive structural alignment among N10, influenza B NAs (with NA from influenza B Beijing/1/87 as the representative), and all available canonical influenza A NA subtypes revealed rmsds for Cα atoms of one N10 monomer relative to the other NAs ranging from 1.463 to 2.757 Å (Table S1). The average rmsd was much higher than that between two canonical influenza A NAs (<1 Å), but only moderately higher than that between canonical influenza A NAs and influenza B NA. N10 is most structurally similar to N1, particularly 09N1, and least related to influenza B NA (Table S1). Therefore, the structural alignment is consistent with the recent phylogenetic analysis indicating that N10 is divergent from all other influenza NAs (7).

Fig. 1.

Overall crystal structure of N10. (A) N10 adopts a typical box-shaped NA tetramer structure, even though the highest primary sequence identity of N10 to all other influenza NAs is only 29%. (B) Each NA monomer has six blades (blades 1–6), with blade 6 of N10 (green) containing three β strands and N2 (magenta) has four β strands. (C) Each N10 monomer contains three N-glycosylation sites: N146, N259, and N269 (presented as sticks in green). (D) Each N10 monomer contains the calcium-binding site conserved in other influenza NA structures. Coordination of the calcium ion (green) is shown by the dashed blue lines. (E) The pocket accommodating sialic acid in the N2-Neu5Ac complex contains a positively charged “edge” region and a negatively charged “platform” region. Here the N2 and N10 structures appear in surface representation with the electrostatic potential scaled from −5kT/e to 5KT/e. (F) The electrostatic potential of the uncomplexed N10 reveals no obvious charge in the canonical sialic acid carboxylate-binding site. Furthermore, the platform located at the bottom of the binding site is positively charged compared with the negatively charged platform in the N2-Neu5Ac complex.

Unexpectedly, N10 was found to not contain four antiparallel β strands in each blade. As illustrated by superimposition with the N2 structure from A/Tokyo/3/67 (H2N2) virus (PDB ID code 1NN2), N10 lacks a β strand in blade 6, which is buried in the protein core, and instead contains a loop structure (Fig. 1B). Two additional unique NA structural features were also found by comparison with available influenza NA structures (excluding the drug escape mutants); N9 derived from tern [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 7NN9] has only three β strands in blade 6, whereas the duck influenza N6 (PDB ID code 1V0Z) lacks one β strand in both blade 4 and blade 6.

A detailed structural analysis confirmed the presence in N10 of the highly conserved N-glycosylation site N146 (N2 numbering is used throughout the text according to the sequence alignment shown in Fig. S1) shared by all known influenza A NA structures. Interestingly, two sites, N259 and N269, were also identified in blade 4 of N10. The N-linked glycans of N259 are located at the bottom of the N10 head and protrude toward the virion membrane, whereas in N269, the glycans are near the top of the head and point away from the center of the putative enzymatic active site (Fig. 1C). Regarding the calcium-binding site, each N10 monomer has the conserved high-affinity site important for stability in all known NAs (19). This site in N10 is formed with slight differences from other NA structures, in which the calcium ion is coordinated by the main chain carbonyl oxygens of N293, D297, G345, and G347; the carbonyl group of the D324 side chain; and a water molecule (Fig. 1D).

Lack of Sialidase Activity.

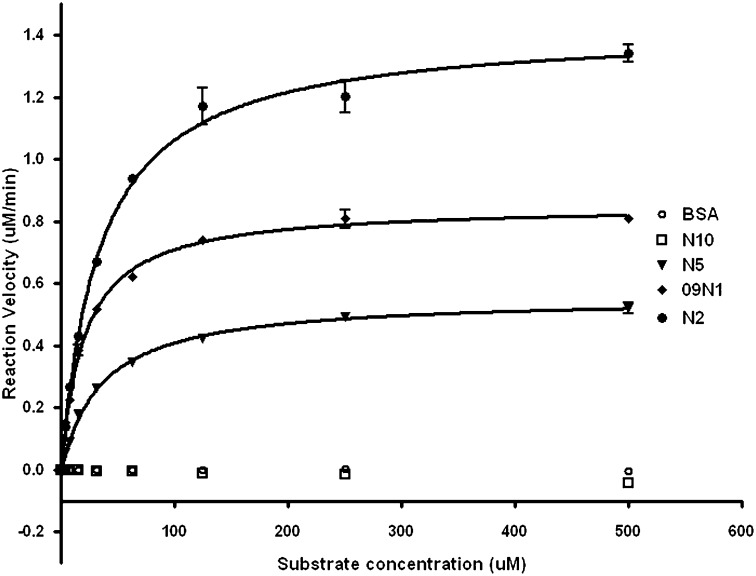

Influenza A virus NAs can be grouped based on their primary sequences (group 1 and group 2) and featured by variant structural properties (open or closed state) of the 150-loop (24). As demonstrated by an in vitro fluorescence-based activity assay, typical group 2 N2, atypical group 1 09N1, and typical group 1 N5 displayed high sialidase activity and similar Km values (20.3–36.1 μM) as reported previously (25, 26). In contrast, N10 exhibited no NA activity at a concentration of 1 μM using the standard NA substrate methylumbelliferyl-N-acetylneuraminic acid (MUNANA) (Fig. 2). Even at a concentration of 10 μM, no N10 activity was detected, demonstrating that N10 lacks sialidase activity and may have an unknown function distinct from canonical influenza NAs.

Fig. 2.

N10 has no sialidase activity. The reaction velocity (μM/min) of NAs is shown based on substrate conversion. Fluorogenic MUNANA substrate was used at a final concentration of 0–500 μM. 09N1 (rhombus), N2 (black cycle), and N5 (triangle) display obvious enzymatic activity, whereas N10 (square) lacks sialidase activity. BSA (white cycle) was used as a negative control. Mean values were determined from at least three duplicates and are presented with SDs indicated by error bars.

Alterations of Conserved NA Active Site Architecture.

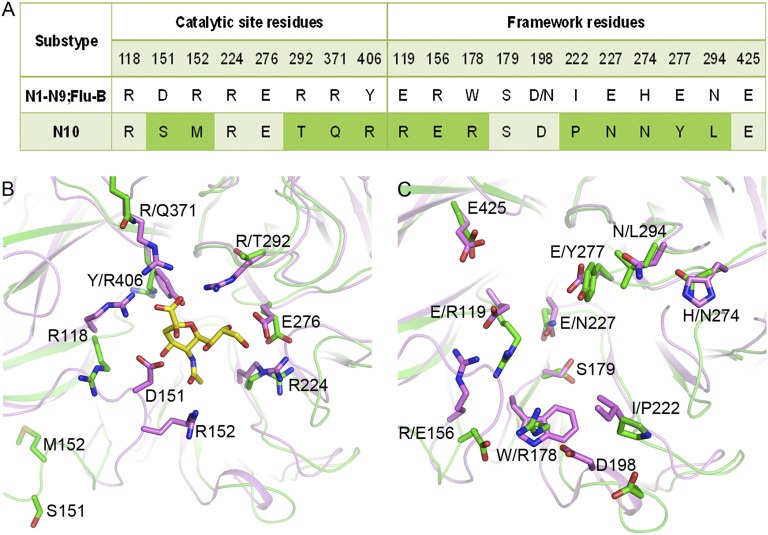

We next investigated the structural basis for the inability of N10 to bind and hydrolyze the sialidase substrate with a terminally linked sialic acid. As illustrated in Figs. 1E and 3 by the N2-Neu5Ac complex (PDB ID code 2BAT), a classical reference structure, the charged pocket accommodating sialic acid in typical influenza A NA, can be divided into two distinct regions. First, there is an important “edge” region consisting of a positively charged arginine triad (R118, R292, and R371), as well as R152 and R224. The arginine triad forms critical high-energy salt bridges with the negatively charged C1 carboxylate of sialic acid, whereas R152 forms a hydrogen bond with the sialic acid N-acetyl group. Second, there is a negatively charged “platform” region composed of E119, E227, E276, and E277, located below the bound sialic acid. E119 and E276 form hydrogen bonds to noncharged portions of the sialic acid, and E276 is thought to play an important role in the catalytic mechanism via interaction with Tyr406 (27). All of these residues, including influenza B, are highly conserved in N1–N9. In contrast, N10 lacks the conserved arginine triad responsible for binding of the sialic acid carboxylate group (Fig. 1F), and the corresponding negatively charged platform region is replaced by a positively charged region in the N10 structure. Why the platform region is negatively charged rather than positively charged or neutral remains unclear, and should be addressed in the near future.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the catalytic site and framework residues in the N2-Neu5Ac complex with those in N10. (A) Sequence alignment shows that 5 of the 8 key catalytic site residues and 8 of the 11 framework residues are substituted in N10. (B) Superimposition of the N10 structure (green) with the N2-Neu5Ac complex structure (magenta) reveals the dramatic changes of the eight catalytic site residues. The natural ligand sialic acid is shown in stick presentation (yellow). (C) Structural comparison of the 11 framework residues in the N2-Neu5Ac complex with the corresponding residues of N10.

In addition, N10 has a more open pseudoactive site cavity, conferring a lower capability, if any, to tightly bind sialic acid (Fig. 1 E and F). More specifically, the key catalytic site residues and the framework residues responsible for stabilizing the active site are highly conserved (with the exception of D/N for residue 198) among N1–N9, as well as influenza B virus NA, but is highly divergent in N10 (Fig. 3A). Surprisingly, N10 contains only three of the eight canonical influenza NA catalytic site residues. The salt bridge between R224 and E276 is maintained in N10. The conformation of E276 is nearly the same as that observed in the NA-oseltamivir complex structures and might be sufficiently flexible to hydrogen-bond with the glycerol group of sialic acid, as reported previously (11, 16). R118 is shifted by 1.20 Å (Cα atom), and the position of its side chain is oriented toward the bottom of the pseudoactive site. Furthermore, residue 371 is found 2.35 Å (Cα atom) away from the center of the referenced NA active site, and both residues 292 and 371 are replaced with shorter polar residues, T and Q, respectively. In addition, residues 151 and 152 are shifted even further away from the pseudoactive site (11.72 and 11.63 Å, respectively, in terms of Cα atoms compared with the N2-Neu5Ac complex). These alterations lead to the loss of the crucial interactions essential for the recognition of the sialidase substrate. Most importantly, the proposed key nucleophilic residue Y406 is replaced by a positively charged R406 in N10 (27), which is unlikely to function in a similar manner, especially with its side chain oriented in the opposite direction relative to the canonical Y406 (Fig. 3B). The deficiency of a key catalytic residue further supports the idea that N10 is not a canonical sialidase.

As stated earlier, only 3 of the 11 framework residues of canonical influenza NAs could be identified in N10. The conformations of both E425 and S179 in N10 resemble those in the N2-Neu5Ac complex; however, the conserved E119, E227, W178, and I222 residues, which also form contacts with sialic acid, are replaced in N10 by R119, N227, R178, and P222, respectively. This both further weakens the sialic acid-binding capability of N10 and greatly contributes to replacement of the highly conserved acidic pocket with a predominantly basic site in N10. Further analysis of the remaining five residues revealed an interesting pattern in which framework residues are altered in coordination with the substitution of key catalytic site residues. In the canonical N2-Neu5Ac complex, E277, N294, H274, and D198 help stabilize the conformation of Y406, R292, E276, and R152, respectively, and R156 is important for stabilizing the conformation of E119 and the 150-loop. Nevertheless, the N10 D198 is shifted 3.6 Å (Cα atom) outward from the center compared with D198 in the N2-Neu5Ac complex. Moreover, the remaining four residues are replaced by Y277, L294, N274, and E156, resulting in significantly different chemical properties (Fig. 3C). Overall, the effects caused by these alterations explain why N10 has a unique pseudoactive site architecture.

Special Features of the 150-Loop.

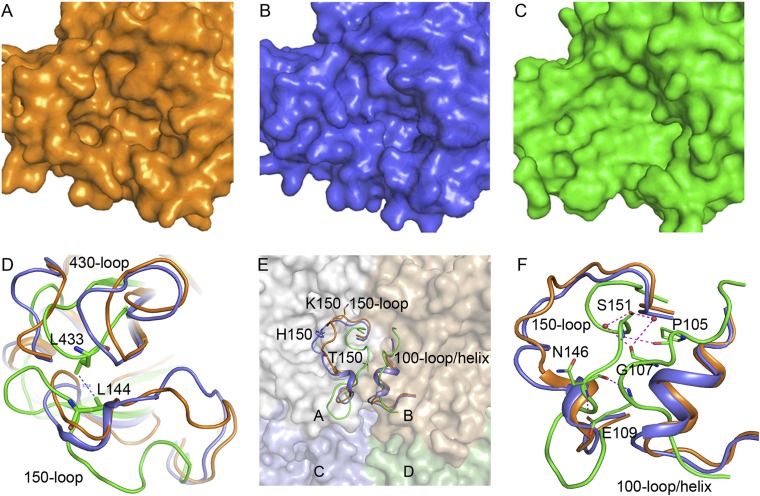

Numerous studies have confirmed that the 150-loop is one of the most flexible parts of the influenza NA structure (28–30), and there are striking structural differences among variant influenza NA subtypes at this site (17, 18, 20). No 150-cavity in N10 could be identified compared with the uncomplexed typical group 1 VN04N1 (NA from Vietnam 2004 H5N1; PDB ID code 2HTY) and typical group 2 N2 structures (Fig. 4 A–C).

Fig. 4.

N10 has a unique 150-loop conformation. (A) Typical group 1 NA:VN04N1 (orange) has the 150-cavity in its active site. (B) Typical group 2 NA: N2 (blue) has no 150-cavity. (C) N10 (green) has a more open pseudoactive site without obvious bounds and lacks the 150-cavity. (D) The 150-loop of N10 (green) adopts an unusually extended conformation, and L144 and L433 in N10 form a stable hydrophobic interaction. (E) The N10 150-loop in one monomer forms strong contacts with the 100-loop of the adjacent monomer, which makes the two loops in N10 much closer compared with those of other influenza NAs. (F) Detailed presentation of the polar interactions between the N10 150-loop of one monomer and the 100-loop of the other monomer. S151 forms one hydrogen bond with P105, and N146 forms two hydrogen bonds with E109. S151 also forms hydrogen bonds with G107 that are mediated by two water molecules.

Detailed comparison of these three structures revealed an abnormally extended conformation of the N10 150-loop, which is located far beyond the VN04N1 active site. The 430-loop of N10 is also moved outward relative to the center of the referenced active sites so as to maintain coordination with the 150-loop, in accordance with other known NAs (18, 28). Compared with the van der Waals interaction between P431 and I149 in 09N1 (PDB ID code 3NSS), L144 forms a more stable hydrophobic interaction with L433 in N10 (Fig. 4D).

In view of a tetrameric N10, the 150-loop of each monomer is positioned much closer to the respective neighboring monomer compared with that in other influenza NAs (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, it is directly involved in the intermolecular interaction at the interface of two NA monomers, which has not been reported previously. There are strong polar contacts between the 150-loop of one N10 molecule and the 100-loop (residues 105–109) of the other. In particular, the S151 main chain nitrogen hydrogen-bonds with the P105 carbonyl, and the N146 carbonyl group forms a hydrogen bond with the E109 peptide bond nitrogen. In addition, two water molecules mediate the interaction of the S151 side chain hydroxyl group with the G107 carbonyl oxygen, whereas the E109 side chain exhibits an extended state to hydrogen-bond with the N146 peptide-bound nitrogen (Fig. 4F). We also noted the consistent presence of a helix in place of the N10 100-loop in all other active influenza NA structures. The unique secondary structure of the N10 100-loop may be attributed primarily to the presence of two proline residues at positions 105 and 108.

Discussion

The bat-derived influenza virus genome N10 protein reported here has been confirmed to have a canonical influenza NA fold. Based on previous sequence analyses (7) and our structural alignment, N10 is highly distinct from influenza B virus NA, as we have shown. Moreover, either the average sequence identity or average structural similarity of N10 to influenza A N1–N9 is lower than that of influenza B NA to influenza A N1–N9. This indicates that it may be inappropriate to designate this bat-derived NA-like molecule as a member of influenza A virus NAs, and that instead N10 might be derived from another, unknown influenza type (either extinct or yet to be identified); however, further investigations are needed to elucidate its true evolutionary origin.

Our biochemical analysis further demonstrates that N10 is unable to function as a canonical sialidase. A recent study revealed that bats are hosts to major viral pathogens from the Paramyxoviridae family (31); thus, we compared the influenza virus N10 with the important attachment glycoprotein (also known as the “vestigial NA”) of several key paramyxoviruses. In terms of both the sequence and overall structure, N10 differs dramatically from the measles virus hemagglutinin (MV-H) (32), Nipah virus G protein (NiV-G) (33), and Hendra virus G protein (HeV-G) (34) (Table S2 and Fig. S2). These attachment proteins play pivotal roles in virus entry and do not contain a calcium-binding site. These findings, together with the presence of the conserved calcium-binding site important for the conformational stability of the canonical influenza NA (25), suggest that N10 may have unknown activity. In this case, the three N-glycosylation sites observed might be important for the stability of N10 as a surface enzyme against proteolytic digestion, as reported previously (19), and also might provide a mechanism through which the bat influenza virus evades host immune recognition (35).

Our detailed structural analysis explains why N10 does not function as a sialidase. With its significantly altered key active site residues, surprisingly open pseudoactive site, and unfavorable surface electrostatic potential, N10 is poorly equipped to bind to sialic acid. Thus, our inability to obtain an N10-sialic acid complex structure from crystal soaking experiments despite great effort is reasonable. Furthermore, taking the hemagglutinin-neuramnidase balance into consideration (36), H17 is also divergent from known HAs, and the H17N10 virus is unable to propagate in either cell cultures or chicken embryos (7). This may further explain why N10 cannot use terminally linked sialic acid receptors (i.e., α2,3- or α2,6-linked type) as its substrate, and why identifying the H17 receptor would be helpful in confirming its actual substrate. Therefore, the currently available influenza NA inhibitors are highly unlikely to be effective against the bat-derived influenza virus if it in fact is an actual pathogen.

More importantly, the unique N10 150-loop was found to participate in the intermolecular interaction between two adjacent NA molecules. The extended conformation of the N10 150-loop is stabilized by strong hydrogen bonds with the 100-loop of the neighboring molecule and may be much less flexible than other influenza NAs. These interactions may limit either the movement on inhibitor binding, as shown in typical group 1 NA crystal structures (17, 19, 20), or the variant conformations in solution, as seen in the molecular dynamics simulations with several group 2 NAs (29, 30). In addition, there is still the possibility that the 150-loop of N10 might not be involved in catalysis, whereas the flexible 150-loop in canonical influenza NA might act as an important switch in the catalytic cycle (37).

Taken together, the data from our successful structural and functional characterization of the bat-derived influenza virus N10 reveal an unusual influenza protein that lacks NA activity despite its canonical NA fold. Not only does the present study offer insight into the structure and function of the sialidase superfamily, it also raises further questions about how the bat influenza virus enters and is released from host cells if in fact it is an actual mammalian virus.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of Influenza Virus NAs.

The preparation procedures for recombinant 09N1, N2, and N5 were as described in our previous reports (18, 20, 24). Recombinant N10 protein was prepared using our established baculovirus expression system. The cDNA encoding the ectodomain (residues 83–460, based on N2 numbering) of influenza A/little yellow-shouldered bat/Guatemala/153/2009(H17N10) NA-like protein N10 was cloned into the pFastBac1 baculovirus transfer vector (Invitrogen). A GP67 signal peptide was added at the N terminus to facilitate secretion of the recombinant protein, followed by a His tag, a tetramerizing sequence, and a thrombin cleavage site (18). Recombinant pFastBac1 plasmid was used to transform DH10BacTM Escherichia coli (Invitrogen). The recombinant baculovirus was obtained following the manufacturer’s protocol, and Hi5 cell suspension cultures were infected with high-titer recombinant baculovirus. After growth of the infected Hi5 suspension cultures for 2 d, centrifuged media were applied to a 5-mL HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare), which was washed with 20 mM imidazole. Then NA was eluted using 300 mM imidazole. After dialysis and thrombin digestion (3 U/mg NA; BD Biosciences) overnight at 4 °C, gel filtration chromatography was performed with a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) with 20 mM Tris⋅HCl and 50 mM NaCl (pH 8.0). High-purity NA fractions were pooled and concentrated using a membrane concentrator with a molecular weight cutoff of 10 kDa (Millipore).

Enzymatic Activity Assay.

The activities of purified 09N1, N2, N5, and N10 were tested using MUNANA (J&K Scientific) as a fluorogenic substrate (26). The appropriate protein and substrate concentrations were chosen after several rounds of preliminary tests. Protein (10 μL) was mixed with 10 μL of buffer containing 33 mM MES and 4 mM CaCl2 (pH 6.0) in each well of a 96-well plate, after which the plate was incubated at 37 °C. The final concentrations were 10 nM for 09N1, 10 nM for N2, 10 nM for N5, 1 μM for N10, and 10 μM for BSA. Serial dilutions (0–500 μM) of preheated MUNANA (30 μL) were then added. The fluorescence intensity of the released product was measured every 30 s for 1 h at 37 °C on a microplate reader (SpectraMax M5; Molecular Devices), with excitation and emission wavelengths of 355 nm and 460 nm, respectively. All assays were performed three or more times, and the Km and Vm values for active NAs were calculated using GraphPad Prism.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination.

N10 crystals were obtained using the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method. N10 protein [1 μL of 10 mg/mL protein in 20 mM Tris and 50 mM NaCl (pH 8.0)] was mixed with 1 μL of reservoir solution [30% (wt/vol) PEG2000 monomethyl ether (MME), 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.6), and 0.2 M ammonium sulfate]. N10 crystals were cryoprotected in mother liquor with the addition of 20% (vol/vol) glycerol before being flash-cooled at 100 K. Diffraction data for N10 were collected at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility beamline BL17U. The collected intensities were indexed, integrated, corrected for absorption, and scaled and merged using HKL-2000 (38). Data collection statistics are summarized in Table S3. The structure of N10 was solved by molecular replacement using Phaser (39) from the CCP4 program suite (40), with the structure of 09N1 (PDB ID code 3NSS) as the search model. The initial model was refined by rigid body refinement using REFMAC5 (41), and extensive model building was performed using COOT (42). Further rounds of refinement were performed using the phenix.refine program implemented in the PHENIX package (43) with energy minimization, isotropic ADP refinement, and bulk solvent modeling. Final statistics for the N10 structure are presented in Table S3. The stereochemical quality of the final model was assessed with PROCHECK (44).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yanfang Zhang for help with protein preparation and the staff at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (beamline 17U) for assistance. This work was supported by National 973 Project Grant 2011CB504703 and National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) Grant 81021003. C.J.V. is the recipient of Chinese Academy of Sciences Fellowship for Young International Scientists 2011Y2SA01 and a research grant from the NSFC Research Fund for Young International Scientists 31150110147. G.F.G. is a leading principal investigator of the NSFC Innovative Research Group.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 4FVK).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1211037109/-/DCSupplemental.

See Commentary on page 18635.

References

- 1.Medina RA, García-Sastre A. Influenza A viruses: New research developments. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:590–603. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumann G, Noda T, Kawaoka Y. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature. 2009;459:931–939. doi: 10.1038/nature08157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu D, Liu X, Yan J, Liu WJ, Gao GF. Interspecies transmission and host restriction of avian H5N1 influenza virus. Sci China C Life Sci. 2009;52:428–438. doi: 10.1007/s11427-009-0062-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao GF, Sun Y. It is not just AIV: From avian to swine-origin influenza virus. Sci China Life Sci. 2010;53:151–153. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-0017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan Y, et al. The emergence of pandemic influenza viruses. Protein Cell. 2010;1(1):9–13. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0008-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Y, et al. In silico characterization of the functional and structural modules of the hemagglutinin protein from the swine-origin influenza virus A (H1N1)-2009. Sci China Life Sci. 2010;53:633–642. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-4010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong S, et al. A distinct lineage of influenza A virus from bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:4269–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116200109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:152–179. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.152-179.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Air GM. Influenza neuraminidase. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6:245–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colman PM, Varghese JN, Laver WG. Structure of the catalytic and antigenic sites in influenza virus neuraminidase. Nature. 1983;303:41–44. doi: 10.1038/303041a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker AT, Varghese JN, Laver WG, Air GM, Colman PM. Three-dimensional structure of neuraminidase of subtype N9 from an avian influenza virus. Proteins. 1987;2:111–117. doi: 10.1002/prot.340020205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varghese JN, McKimm-Breschkin JL, Caldwell JB, Kortt AA, Colman PM. The structure of the complex between influenza virus neuraminidase and sialic acid, the viral receptor. Proteins. 1992;14:327–332. doi: 10.1002/prot.340140302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chong AK, Pegg MS, Taylor NR, von Itzstein M. Evidence for a sialosyl cation transition-state complex in the reaction of sialidase from influenza virus. Eur J Biochem. 1992;207:335–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Itzstein M, et al. Rational design of potent sialidase-based inhibitors of influenza virus replication. Nature. 1993;363:418–423. doi: 10.1038/363418a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim CU, et al. Influenza neuraminidase inhibitors possessing a novel hydrophobic interaction in the enzyme active site: Design, synthesis, and structural analysis of carbocyclic sialic acid analogues with potent anti-influenza activity. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:681–690. doi: 10.1021/ja963036t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varghese JN, et al. Drug design against a shifting target: A structural basis for resistance to inhibitors in a variant of influenza virus neuraminidase. Structure. 1998;6:735–746. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell RJ, et al. The structure of H5N1 avian influenza neuraminidase suggests new opportunities for drug design. Nature. 2006;443:45–49. doi: 10.1038/nature05114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q, et al. The 2009 pandemic H1N1 neuraminidase N1 lacks the 150-cavity in its active site. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1266–1268. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu X, Zhu X, Dwek RA, Stevens J, Wilson IA. Structural characterization of the 1918 influenza virus H1N1 neuraminidase. J Virol. 2008;82:10493–10501. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00959-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang M, et al. Influenza A virus N5 neuraminidase has an extended 150-cavity. J Virol. 2011;85:8431–8435. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00638-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudrawar S, et al. Novel sialic acid derivatives lock open the 150-loop of an influenza A virus group-1 sialidase. Nat Commun. 2010;1:113. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohan S, McAtamney S, Haselhorst T, von Itzstein M, Pinto BM. Carbocycles related to oseltamivir as influenza virus group-1–specific neuraminidase inhibitors: Binding to N1 enzymes in the context of virus-like particles. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7377–7391. doi: 10.1021/jm100822f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, et al. Crystal structure of the swine-origin A (H1N1)-2009 influenza A virus hemagglutinin (HA) reveals similar antigenicity to that of the 1918 pandemic virus. Protein Cell. 2010;1:459–467. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0059-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vavricka CJ, et al. Structural and functional analysis of laninamivir and its octanoate prodrug reveals group specific mechanisms for influenza NA inhibition. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002249. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chong AK, Pegg MS, von Itzstein M. Influenza virus sialidase: Effect of calcium on steady-state kinetic parameters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1077:65–71. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(91)90526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yen HL, et al. Hemagglutinin-neuraminidase balance confers respiratory-droplet transmissibility of the pandemic H1N1 influenza virus in ferrets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14264–14269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Itzstein M. The war against influenza: Discovery and development of sialidase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:967–974. doi: 10.1038/nrd2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amaro RE, et al. Remarkable loop flexibility in avian influenza N1 and its implications for antiviral drug design. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7764–7765. doi: 10.1021/ja0723535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amaro RE, Cheng X, Ivanov I, Xu D, McCammon JA. Characterizing loop dynamics and ligand recognition in human- and avian-type influenza neuraminidases via generalized born molecular dynamics and end-point free energy calculations. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4702–4709. doi: 10.1021/ja8085643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amaro RE, et al. Mechanism of 150-cavity formation in influenza neuraminidase. Nat Commun. 2011;2:388. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drexler JF, et al. Bats host major mammalian paramyxoviruses. Nat Commun. 2012;3:796. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colf LA, Juo ZS, Garcia KC. Structure of the measles virus hemagglutinin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1227–1228. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu K, et al. Host cell recognition by the henipaviruses: Crystal structures of the Nipah G attachment glycoprotein and its complex with ephrin-B3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9953–9958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804797105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowden TA, Crispin M, Harvey DJ, Jones EY, Stuart DI. Dimeric architecture of the Hendra virus attachment glycoprotein: Evidence for a conserved mode of assembly. J Virol. 2010;84:6208–6217. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00317-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vigerust DJ, Shepherd VL. Virus glycosylation: Role in virulence and immune interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner R, Matrosovich M, Klenk HD. Functional balance between haemagglutinin and neuraminidase in influenza virus infections. Rev Med Virol. 2002;12:159–166. doi: 10.1002/rmv.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vavricka CJ, et al. Special features of the 2009 pandemic swine-origin influenza A H1N1 hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. Chin Sci Bull. 2011;56:1747–1752. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Read RJ. Pushing the boundaries of molecular replacement with maximum likelihood. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:1373–1382. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901012471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12):2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laskowski RA, Macarthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.