Abstract

Ric-8A (resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 8A) and Ric-8B are guanine nucleotide exchange factors that enhance different heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide–binding protein (G protein) signaling pathways by unknown mechanisms. Because transgenic disruption of Ric-8A or Ric-8B in mice caused early embryonic lethality, we derived viable Ric-8A– or Ric-8B–deleted embryonic stem (ES) cell lines from blastocysts of these mice. We observed pleiotropic G protein signaling defects in Ric-8A−/− ES cells, which resulted from reduced steady-state amounts of Gαi, Gαq, and Gα13 proteins to <5% of those of wild-type cells. The amounts of Gαs and total Gβ protein were partially reduced in Ric-8A−/− cells compared to those in wild-type cells, and only the amount of Gαs was reduced substantially in Ric-8B−/− cells. The abundances of mRNAs encoding the G protein α subunits were largely unchanged by loss of Ric-8A or Ric-8B. The plasma membrane residence of G proteins persisted in the absence of Ric-8 but was markedly reduced compared to that in wild-type cells. Endogenous Gαi and Gαq were efficiently translated in Ric-8A−/− cells but integrated into endomembranes poorly; however, the reduced amounts of G protein α subunits that reached the membrane still bound to nascent Gβγ. Finally, Gαi, Gαq, and Gβ1 proteins exhibited accelerated rates of degradation in Ric-8A−/− cells compared to those in wild-type cells. Together, these data suggest that Ric-8 proteins are molecular chaperones required for the initial association of nascent Gα subunits with cellular membranes.

INTRODUCTION

Resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 8A (Ric-8A) and Ric-8B are guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for the α subunits of heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide–binding proteins (G proteins) (1, 2). Ric-8A stimulates the intrinsic nucleotide exchange rates of three of the four classes of G protein α subunits, Gαi, Gαq, and Gα12/13, whereas Ric-8B is a GEF for Gαs. RIC-8 was discovered during a genetic screen of Caenorhabditis elegans that was designed to uncover mutants with defective neurotransmitter release (3). Genetically, the single C. elegans Ric-8 protein was predicted to act upstream of, or in parallel with, Gαq and Gαs to regulate synaptic vesicle priming and to work with Gαo to control centrosome movements (4-6). The role of Ric-8 in regulation of mitotic spindle pole movements with complexes containing Gαi/o and GoLoco proteins has been dissected in detail and is conserved in worms, flies, and mammals (7-12). In mammalian cells, Ric-8A appears to potentiate Gαq signaling, and Ric-8B overexpression enhances activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC) by Gs and Golf (13-15). This latter finding resulted in a technical advance, namely, that Ric-8B enabled efficient odorant coupling to Golf in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells reconstituted with odorant receptors (16, 17).

The positive roles that Ric-8 proteins have on divergent G protein signaling pathways are consistent with the capacities of Ric-8A and Ric-8B to collectively act as GEFs for all classes of G protein α subunits; however, there has been no demonstration of the GEF activities of Ric-8 proteins in cells, and it is unclear whether they directly activate G proteins to evoke effector enzyme signaling outputs. An alternative hypothesis for the regulation of G protein function by Ric-8 proteins was originally proposed from work with Drosophila Ric-8. Mutants of Drosophila Ric-8 or Ric-8–specific RNA interference (RNAi) result in defective asymmetric cell division and, consequently, the unorganized gastrulation of embryos and differentiation of neuroblasts (18-20). The abundances of Gαi/o and Gβ proteins are also reduced in these mutants, and these G proteins are mislocalized to undescribed cytosolic puncta. Similarly, a reduction in the amount of the Gαi homolog Gpa16 in so-called cortical crescents (plasma membrane) is observed in mitotic ric-8 reduction-of-function mutant C. elegans embryos (21). Ric-8B enhances the amounts of Gαolf and Gαs in cultured mammalian cells (13, 22). The abundance of recombinant G protein α subunit in Sf9 insect cells was increased greatly by co-infection with recombinant Ric-8A– or Ric-8B–expressing baculoviruses and provided an enhanced method for the purification of all classes of G protein α subunits (23). Together, these results suggest that a function of Ric-8 proteins is to promote G protein biosynthesis or to stabilize mature G proteins.

G protein biosynthesis is a complex process that begins with the translation of Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits on free ribosomes. The cytosolic chaperonin–containing t-complex polypeptide 1 (CCT) mediates the folding of Gαt (transducin) and Gβ (24, 25). The co-chaperone protein phosducin-like protein-1 (PhLP-1) acts with CCT to fold nascent Gβ subunits and assemble Gβγ dimers. Gβ is released from the CCT in a complex with PhLP-1. Dopamine receptor–interacting protein 78 (DRIP78)–promoted folding of nascent Gγ precedes the formation of a PhLP-1–GβGγ ternary complex that translocates to the outer leaflet of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane (26-29). Isoprenylation of the C-terminal CAAX motif of Gγ anchors the nascent Gβγ dimer in the membrane (30, 31). The events underlying the attachment of Gα subunits to the ER membrane and initial association with Gβγ dimers are less well understood. No chaperone or escort factor, such as PhLP-1 or DRIP78, is known to work with the CCT to fold or process G protein α subunits. Once Gα binds to the ER-associated Gβγ dimer and becomes palmitoylated, the intracellularly formed G protein heterotrimers are trafficked to the plasma membrane (32, 33). All members of the Gαi class of G proteins are also myristoylated irreversibly during translation (34). Myristoylated Gαi has enhanced affinity for the membrane and increased receptor coupling compared to unmodified Gαi (35, 36).

Mature heterotrimeric G proteins traffic among the plasma membrane and locales within the cytoplasm through mechanisms that are either dependent or independent of G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) action (37-40). Trafficking can be vesicle-mediated or diffusive and, in one case, may be regulated by a cycle of dynamic G protein palmitoylation and depalmitoylation. Depalmitoylated G protein α subunits at the plasma membrane are transported to the Golgi to become repalmitoylated by Golgi-resident aspartate-histidine-histidine-cysteine (DHHC) palmitoyl transferases and are then recycled back to the plasma membrane (41, 42). It is not clear how G proteins are transported by so-called diffusive mechanisms. Factors that might aid or escort G proteins during diffusive shuttling processes have yet to be defined.

To investigate the mechanism by which mammalian Ric-8A and Ric-8B regulate heterotrimeric G protein function in vivo, we created transgenic mice with single deletions of Ric-8A or Ric-8B. Complete knockouts of these genes resulted in mouse strains that were not viable and died early during embryogenesis [before embryonic day 8.5 (E8.5)]. An independently derived Ric-8A knockout mouse was also not viable and exhibited early embryonic lethality and severe gastrulation defects (43). As neither knockout mouse was born, we derived Ric-8A−/− or Ric-8B−/− embryonic stem (ES) cell lines from viable blastocysts for the purpose of creating cultured cell models with which to study G protein function in the complete absence of Ric-8A or Ric-8B. We observed pleiotropic G protein signaling defects in the Ric-8A–null cell lines, which we attributed to a >95% reduction in the steady-state abundances of Gαi, Gαq, and Gα13 proteins and partial reductions in the amounts of Gαs and total Gβ. The abundance of Gαs alone was reduced ~85% in Ric-8B–null cells. In Ric-8A–null cells, the translation of Gαi and Gαq proceeded normally, but both nascent G protein α subunits were defective in initial association with the membrane. Much of the nascent Gα subunits remained soluble and were rapidly degraded. Thus, we conclude that Ric-8 proteins control G protein abundance and function by acting as molecular chaperones that mediate the initial association of G protein α subunits with an endomembrane.

RESULTS

Ric-8A−/− and Ric-8B−/− mouse ES cell lines derived from blastocysts are viable

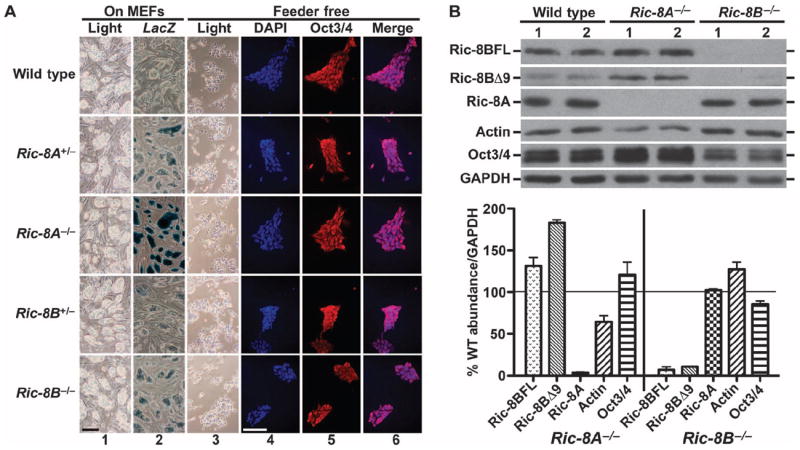

Transgenic Ric-8A– or Ric-8B–deleted C57BL/6J mice were created with VelociGene technology (44). The complete Ric-8A coding sequence or the first three exons and a portion of the third intron of Ric-8B were replaced with LacZ expression cassettes under the control of the endogenous Ric-8 promoters (fig. S1). Homozygous Ric-8A−/− or Ric-8B−/− mice were not born and exhibited lethality before E8.5 (n > 100 mice). Heterozygote mice of each strain were reproductive and had no obvious defects. Fifty-three and 49 preimplantation blastocysts (chemically delayed from E3.5 to E6.5) were harvested from Ric-8A+/− or Ric-8B+/− intercrosses and grown in culture. Viable inner cell masses were detached and subcultured to enable outgrowth of mouse ES (mES) cell lines. Those surviving derivation resulted in four Ric-8A+/+, nine Ric-8A+/−, three Ric-8A−/−, one Ric-8B+/+, three Ric-8B+/−, and seven Ric-8B−/− viable mES cell lines as determined by genomic polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based genotyping (fig. S1). Ric-8A and Ric-8B were not required for embryonic development of viable blastocysts, placing the timing of embryonic death between E4 and E8.5 for both gene deletions. No obvious morphological differences were observed among mES cell lines cultured on mitotically inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or in feeder-free culture (Fig. 1A). Ric-8A and Ric-8B promoters were active in mES cell colonies. Dose-dependent β-galactosidase activity was observed as a function of LacZ reporter gene copy number (Fig. 1A). mES cell colonies of each genotype uniformly expressed the pluripotency marker Oct3/4 (Fig. 1A) (45).

Fig. 1.

Mouse ES cell lines derived from blastocysts deficient in Ric-8A or Ric-8B are viable. (A) Wild-type (C57BL/6J), Ric-8A+/−, Ric-8A−/−, Ric-8B+/−, and Ric-8B−/− mES cell lines were derived from blastocysts and cultured on mitotically inactivated wild-type MEFs (columns 1 and 2) and adapted to grow in feeder-free culture (columns 3 to 6). β-Galactosidase activity from LacZ transgenes under control of the endogenous Ric-8A or Ric-8B promoters was measured in each cell line (column 2). mES colonies were costained with DAPI (column 4) and with antibody against Oct3/4 (column 5) to show homogeneous Oct3/4 abundance (Merge, column 6). Scale bar, 200 μm. (B) Quantitative Western blotting analysis of the amounts of Ric-8A, Ric-8B, actin, Oct3/4, and GAPDH was performed with whole-cell lysates prepared from two independently derived wild-type (WT), Ric-8A−/−, and Ric-8B−/− mES cell lines. The amounts of the indicated proteins relative to that of GAPDH were quantified by pixel densitometry analysis with Adobe Photoshop 4.0 (Adobe Systems Inc.). Error bars represent the means ± SEM of three experiments with averaged results from two independent cell lines of each genotype.

Relative amounts of Ric-8A and Ric-8B were measured by quantitative Western blotting of whole-cell lysates prepared from two independently derived wild-type, Ric-8A−/−, and Ric-8B−/− cell lines. Ric-8A and two Ric-8B isoforms (Ric-8BFL and Ric-8BΔ9) were not found in the Ric-8A−/− or Ric-8B−/− cell lines, respectively (Fig. 1B). The amounts of the Ric-8BFL and Ric-8BΔ9 isoforms were increased ~30 and ~80%, respectively, in the Ric-8A−/− cells compared to those in wild-type cells, and the amount of actin was reduced by 40%. The amounts of Ric-8A and actin were unchanged in the Ric-8B–deleted cells.

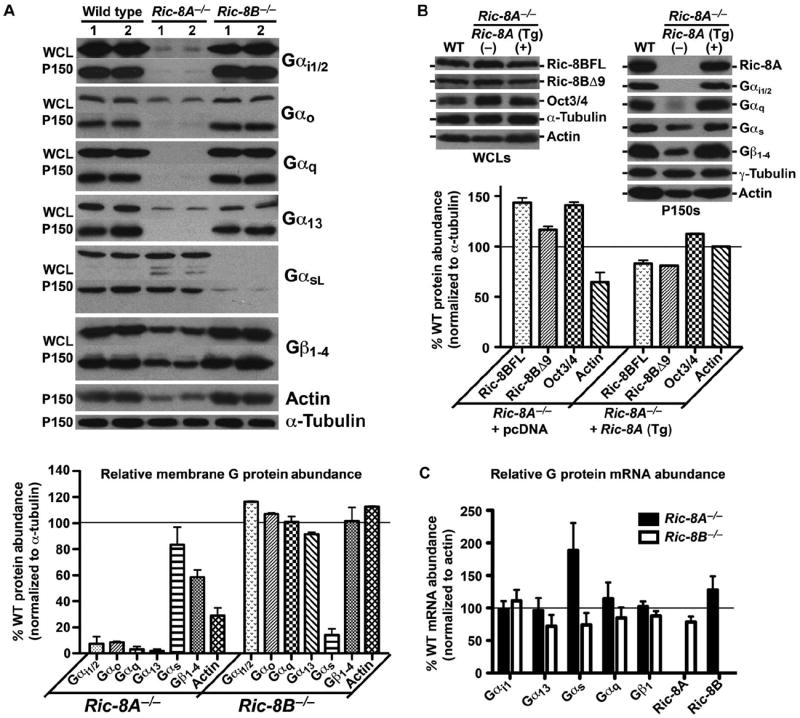

Ric-8A and Ric-8B are required to maintain normal amounts of G protein subunits at steady state

We tested the effects of complete ablation of Ric-8A or Ric-8B on steady-state G protein amounts in crude membrane fractions (150,000g pellets, P150) and whole-cell lysates prepared from duplicate wild-type, Ric-8A−/−, and Ric-8B−/− mES cell lines. Equal amounts of total protein (20 μg of P150 fraction and 60 μg of whole-cell lysate) were analyzed by Western blotting with G protein subunit–specific antisera (Fig. 2A). In both Ric-8A−/− cell lines, we observed a marked reduction in the amounts of Gαi1/2, Gαo, Gαq, and Gα13 in the membrane to <5% of those of wild-type cells. The amount of total Gβ (including Gβ1 to Gβ4) was reduced by 40% compared to that in wild-type cells, and the amount of membrane Gαs was reduced modestly (~20%). The amount of Gαs protein in the membrane of both Ric-8B−/− cell lines was reduced by 85% compared to that of wild-type cells, but the amounts of all other G proteins were similar to those of wild-type cells. In whole-cell lysates from Ric-8A−/−or Ric-8B−/− cells, the same patterns of overall reduction in the amounts of G proteins were observed, with the exception of Gαs in the Ric-8A−/− cells. The magnitude of the reductions in the amounts of Gαo, Gα13, and Gαs in whole-cell lysates of Ric-8A−/− cells was not great as those in the membrane fraction, indicating that the overall defects in G protein abundance were likely a consequence of Ric-8–mediated association of G proteins with the membrane or stabilization of G proteins at the membrane after attainment of membrane residence. In the absence of Ric-8A, some G proteins were partially shifted to the soluble fraction. The amount of polymerized actin (F-actin) was also reduced in the Ric-8A−/− cells compared to that in wild-type cells, but no such reduction occurred in the Ric-8B–deleted cell lines.

Fig. 2.

Steady-state amounts of heterotrimeric G proteins are selectively abrogated in Ric-8A– or Ric-8B–deleted mES cells. (A) Whole-cell lysates (WCL) or crude membrane fractions (from 150,000g centrifugation, P150) prepared from two independently derived wild-type, Ric-8A−/−, and Ric-8B−/− mES cell lines were subjected to quantitative Western blotting for actin, α-tubulin, and the G protein subunits Gαi1/2, Gαo, Gαq, Gα13, Gαs, and total Gβ1. The amounts of the indicated proteins in membrane fractions compared to that of α-tubulin were quantified by pixel densitometry, as described earlier. Error bars represent the means ± SEM obtained from duplicate cell lines of each genotype. (B) Stable expression of the Ric-8A cDNA as a trans-gene (Tg) in a Ric-8A−/− cell line restored G protein and actin protein amounts as determined by quantitative Western blotting. Error bars represent the means ± SEM. (C) Relative amounts of Gαi1, Gα13, Gαs, Gαq, Gβ1, Ric-8A, and Ric-8B mRNAs in Ric-8A−/− and Ric-8B−/− cell lines were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Error bars represent the means ± SEM obtained from duplicate, independently derived cell lines of each genotype.

Gα and Gβγ subunit abundances are interdependent (33). We tested whether transient transfection of Ric-8A−/− and Ric-8B−/− mES cell lines with plasmids encoding FLAG-tagged Gβ1 and Gγ2 subunits would rescue the steady-state deficits in G protein α subunits in these cell lines (fig. S2). In Ric-8A−/− cells, transient overexpression of Gβγ restored the amount of Gαs in crude membranes to that of wild-type cells, but the amount of Gαi1/2 was only rescued from 2.2 to 3.5% of that of wild-type cells. We observed similar percentages in the Gβγ-dependent increase in the amounts of membrane-associated Gαs and Gαi1/2 in wild-type cells. In Ric-8B−/− cells, the amount of membrane Gαi1/2 was increased in response to the increase in Gβγ abundance, but the amount of membrane Gαs remained reduced at ~6% of that of wild-type cells.

We then performed genetic complementation tests of the Ric-8A– or Ric-8B–null cell defects. A Ric-8A−/− mES cell line made to stably express human Ric-8A complementary DNA (cDNA) as a transgene (Tg) did not exhibit the defects in G protein and F-actin abundance that were observed in Ric-8A−/− cells, and restored the amounts of Ric-8BFL and Ric-8BΔ9 to amounts similar to those in wild-type cells (Fig. 2B). We could not generate genetically complemented Ric-8B−/− cell lines because stable expression of cDNA encoding Ric-8BFL or Ric-8BΔ9 in mES cells seemed to be repressed. The abundance of the mES cell pluripotency marker Oct3/4 in Ric-8A−/− cells was 40% greater than that in wild-type cells but was reduced to ~10% above that of wild-type cells upon complementation with Ric-8A. The absence of Ric-8A may contribute to the increased pluripotent potential of mES cells, a role consistent with observations that the single ric-8 genes of C. elegans and Drosophila are required for asymmetric cell division and differentiation (10, 46).

We conducted quantitative PCR analyses comparing the relative abundances of G protein subunit mRNAs in wild-type mES cell lines with those in Ric-8A−/− or Ric-8B−/− cell lines to test the possibility that Ric-8 proteins regulated G protein abundance through a pretranslational mechanism (Fig. 2C). The relative amounts of Gαi, Gα13, Gαq, and Gβ mRNAs remained largely unchanged in the Ric-8A–null and Ric-8B–null cell lines compared to those in wild-type cells. The abundance of Gαs mRNA was increased twofold in the Ric-8A−/− cell lines compared to that in wild-type cells, perhaps through a compensatory mechanism. A modest increase in the abundance of Ric-8B mRNA was observed in the Ric-8A−/− cells, which coincided with the increased amounts of Ric-8BFL and Ric-8BΔ9 proteins.

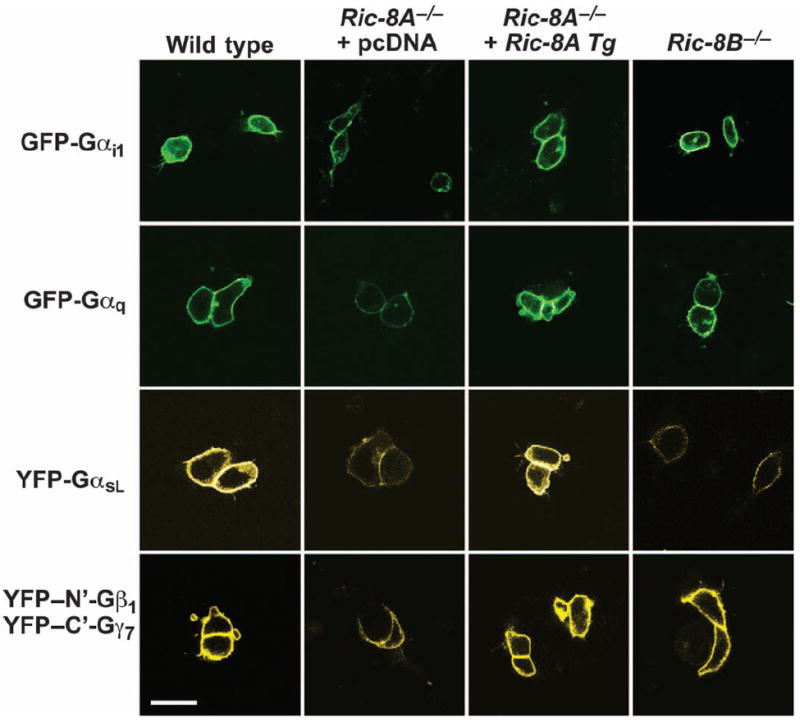

G proteins are reduced in abundance but not absent from the plasma membrane in Ric-8A– and Ric-8B–null mES cells

To assess the residency of G protein α subunits and Gβγ dimers in the plasma membranes of wild-type, Ric-8B−/−, and Ric-8A−/− cells, we transiently transfected the mES cell lines with plasmids encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP)– or yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)–tagged G protein α subunits and a split YFP pair that reconstituted the Gβ1γ7 dimer (Fig. 3) (47). Analysis of confocal microscopy images revealed that GFP-Gαi, GFP-Gαq, YFP-GαsL, and split YFP-Gβ1γ7 were present in the plasma membranes of Ric-8A–deleted cells, but at substantially reduced intensities compared to those in the plasma membranes of transfected wild-type cells. In the Ric-8A−/− cell line expressing the Ric-8A cDNA, the fluorescence intensities of each expressed G protein in the plasma membrane were restored. In the Ric-8B−/− cells, only YFP-GαsL exhibited a reduced intensity in the plasma membrane. These results were consistent with the patterns of reduced abundances of endogenous G proteins at steady state that were observed earlier (Fig. 2). We conclude that Ric-8 proteins are not essential for the trafficking of overexpressed G protein heterotrimers to the plasma membrane but are indeed necessary to establish or maintain normal amounts of G proteins in the membrane.

Fig. 3.

G proteins are localized less efficiently at the plasma membrane in Ric-8A– or Ric-8B–deleted mES cells than in wild-type cells. Wild-type mES cells, Ric-8A−/− mES cells stably expressing pcDNA or Ric-8A cDNA transgene (Tg), and Ric-8B−/− mES cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding GFP-Gαi1, GFP-Gαq, and YFP-GαsL or the split YFP constructs, YFP–N′-Gβ1 and YFP–C′-Gγ7. Cells were visualized by confocal fluorescence microscopy. The signal gain in these images was uniformly enhanced to observe the weak plasma membrane–localized fluorescence of G proteins in the respective Ric-8−/− cells. The enhancement resulted in some saturated cell images, such that the apparent differences in G protein plasma membrane signal intensity are not linear. Scale bar, 20 μm.

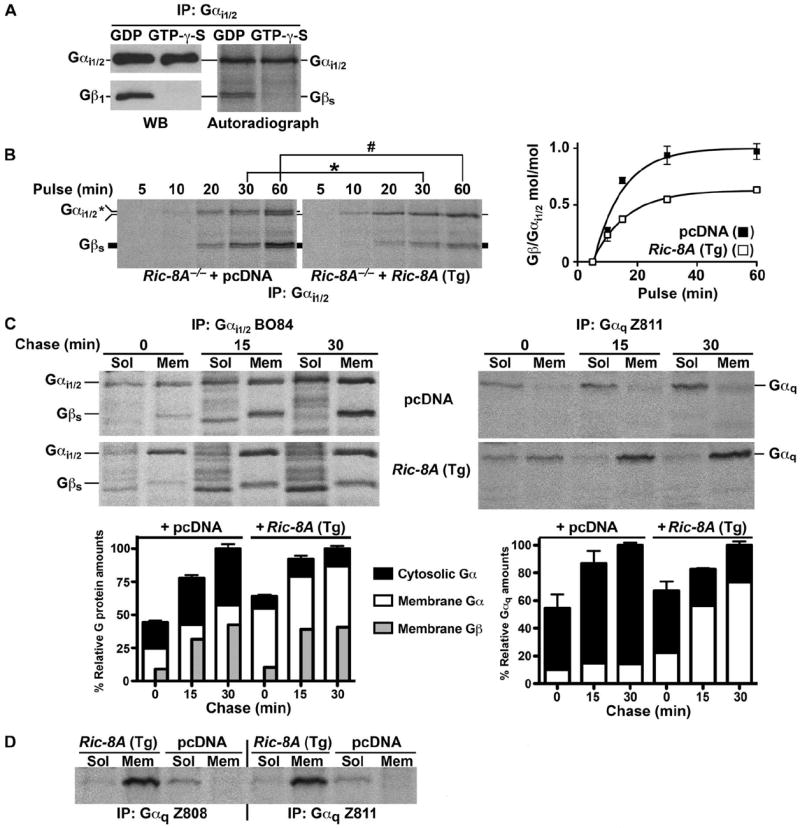

The biosynthesis and initial association of G proteins with intracellular membranes are defective in Ric-8A−/− mES cells

The reduced abundances of select G protein α subunits in Ric-8A– or Ric-8B–null cells might be accounted for if Ric-8 proteins functioned as chaperones that escorted nascent G protein α subunits to the membrane, aided the folding of nascent G α subunits, or both. We developed metabolic labeling and coimmunoprecipitation procedures to address the mechanism of synthesis of G protein α subunits and assembly of G protein heterotrimers in Ric-8A−/− cells. Wild-type mES cells were first labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S] cysteine for 60 min. Labeled whole-cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antiserum (B084) against Gαi1/2 (48) in the presence of guanosine diphosphate (GDP) or Mg2+ and guanosine 5′-O-(3′-thiotriphosphate) (GTP-γ-S). Gβγ is dissociated from Gα when the latter becomes bound to GTP-γ-S. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiserum against Gαi1/2 and antiserum (U49) against Gβ1 (48), or were subjected to autoradiography. When GTP-γ-S was included, Gβ1 was not present in the Gαi1/2 immunoprecipitates, and two prominent ~37-kD bands were also absent on the autoradiograph (Fig. 4A). We concluded that these bands represented two or more endogenous Gβ isoforms that bound to endogenous Gαi1/2.

Fig. 4.

Nascent Gαi1/2 and Gαq are defective in their initial association with the membrane in Ric-8A–deleted mES cells. (A) Nucleotide-dependent coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous Gαi1/2 and Gβ subunits. WCLs from wild-type mES cells that were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine for 1 hour and were supplemented with GDP or Mg+2–GTP-γ-S were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with antiserum against Gαi1/2. The immunoprecipitated samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to autoradiography or were analyzed by Western blotting (WB) for Gαi1/2 and Gβ1. (B) Nascent Gαi1/2 synthesis and association with nascent Gβ subunits over a 1-hour time course of metabolic pulse labeling. Ric-8A−/− mES cells expressing pcDNA or Ric-8A (Tg) were metabolically labeled for the indicated times. WCLs were prepared and subjected to quantitative immunoprecipitation with antiserum against Gαi1/2. Immunoprecipitated Gαi1/2 and associated Gβ subunits were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. Molar ratios of the amount of Gβ to that of Gαi1/2 were quantified by pixel densitometry, as described earlier, after factoring in a 22:18 ratio of methionines and cysteines within the two processed proteins. Error bars represent the means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.0085; #P < 0.0091. (C) Subcellular fractionation of newly synthesized Gαq and Gαi1/2 with associated nascent Gβ subunits was measured after metabolic pulse (10 min) and chase (to 30 min) labeling of Ric-8A−/− cells expressing sham cDNA or Ric-8A cDNA. Labeled proteins were immunoprecipitated from cytosolic (Sol) and crude membrane (Mem) fractions and subjected to quantitative autoradiography. Error bars on the accompanying histographs represent the means ± SEM of three independent experiments. (D) Metabolic 2-hour pulse-labeling and subcellular fractionation analysis of Gαq in cytosolic (Sol) and crude membrane (Mem) fractions was measured by immunoprecipitation with antisera against Gαq (Z808 and Z811). The panel shown is representative of three independent experiments.

We next measured the time course of Gαi1/2 synthesis and its association with nascent Gβγ subunits in the Ric-8A−/− and genetically complemented mES cell lines. The mES cells were metabolically pulse-labeled for up to 1 hour and subjected to immunoprecipitation with antiserum against Gαi1/2 at the indicated times (Fig. 4B). Gαi1/2 was synthesized at equivalent rates in Ric-8A−/− cells stably expressing pcDNA or the human Ric-8A cDNA (Tg), showing that the translation of G protein α subunits was not affected by the loss of Ric-8A; however, we uncovered other differences between these cell lines. In the Ric-8A−/− cells, two Gαi species of different apparent molecular masses were reproducibly recovered from the Gαi1/2 immunoprecipitates over the course of the pulse labeling study, whereas only one species of lower apparent mobility was recovered from the Ric-8A–complemented Ric-8A−/− cells (Fig. 4B and fig. S3). At 60 min of cell labeling, the ratio of the two Gαi1/2 species approached 1:1 in the Ric-8A−/− cells. Before this, most of the nascent Gαi1/2 had a higher apparent mobility. Gαi subunits are myristoylated cotranslationally, and the modified and unmodified forms can be resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (1, 34, 49). We tested whether these might be the two forms of nascent Gαi observed in Ric-8A−/− cells by examining the SDS-PAGE mobilities of transiently expressed Glu-Glu–tagged wild-type Gαi1 or the myristoylation-defective mutant Gαi1 G2A (fig. S3). Nascent, wild-type Glu-Glu–tagged Gαi1 migrated distinctly faster than did Glu-Glu–tagged G2A Gαi1, as was expected for the myristoylated protein; however, a wild-type Glu-Glu–tagged Gαi1 doublet could not be resolved in samples from Ric-8A−/− cells that were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibody against Glu-Glu despite the clear resolution of Glu-Glu–tagged wild-type Gαi1 and Glu-Glu–tagged G2A Gαi1 in adjacent lanes. This suggested that the endogenous nascent Gαi doublet observed in the Ric-8A−/− cell lines might not correspond to the myristoylated and unmodified forms of the protein. Gαi may be subject to a hitherto unknown modification during early biosynthesis that is revealed when Ric-8A is not present.

Next, we investigated the temporal association of newly synthesized Gαi1/2 and Gαq with cell membranes and the formation of Gi heterotrimers. Ric-8A−/− cells expressing Ric-8A (Tg) or sham cDNA were pulse-labeled for 10 min and were fractionated into soluble and crude membranes by centrifugation at different chase times (0, 15, and 30 min). Gαi1/2 or Gαq was immunoprecipitated from the subcellular fractions and visualized with coimmunoprecipitating Gβγ by autoradiography (Fig. 4C). Gβγ was not efficiently coimmunoprecipitated with the antiserum against Gαq. At each time of chase, ~45 to 50% of the newly made Gαi1/2 and ~90% of the newly made Gαq was defectively retained in the soluble fraction of Ric-8A−/− cells. The reduced portion of nascent Gαi1/2 that fractionated with membranes in the Ric-8A−/− cells became bound to Gβγ with high stoichiometry (~1:1). In the Ric-8A–complemented Ric-8A−/− cells, membrane-associated nascent Gαi1/2 reached a stoichiometry of only ~0.4 to 0.6 mol of Gβγ per mole of Gαi1/2. These results are consistent with the Gαi:Gβγ stoichiometry measurements made in the whole-cell pulse-labeling experiment (Fig. 4B), but were unexpected given the defects in the steady-state amounts of Gαi1/2 and total Gβγ in the Ric-8A−/− cells. We speculate that cotranslationally myristoylated Gαi is better able to complete initial endomembrane association in the absence of Ric-8A than are other classes of G protein α subunits because these other α subunits are not myristoylated. Although the overall abundance of nascent membrane-bound Gβγ may also be reduced in Ric-8A−/− cells, the availability of free Gβγ sites to accept nascent, myristoylated Gαi may actually be higher because of the bulk reduction in the amounts of all membrane Gα subunits.

The defect in the association of Gαq with membranes was more marked than that of Gαi1/2 in Ric-8A−/− cells, and we reasoned that a lengthened kinetic delay might account for this defect. We immunoprecipitated Gαq with two polyclonal Gαq-specific antisera (Z808 and Z811) from subcellular fractions of cells pulse-labeled for 2 hours (which approximated the steady-state condition) (Fig. 4D). Nearly all of the Gαq was membrane-associated in Ric-8A–complemented Ric-8A−/− mES cells, but a reduced quantity was present predominantly in the cytosol of Ric-8A−/− cells. Unlike Gαi1, nascent Gαq is not cotranslationally lipidated and it has a stringent requirement for Ric-8A for its initial membrane association.

Enhanced G protein turnover accounts for reduced steady-state amounts in Ric-8A–null mES cells

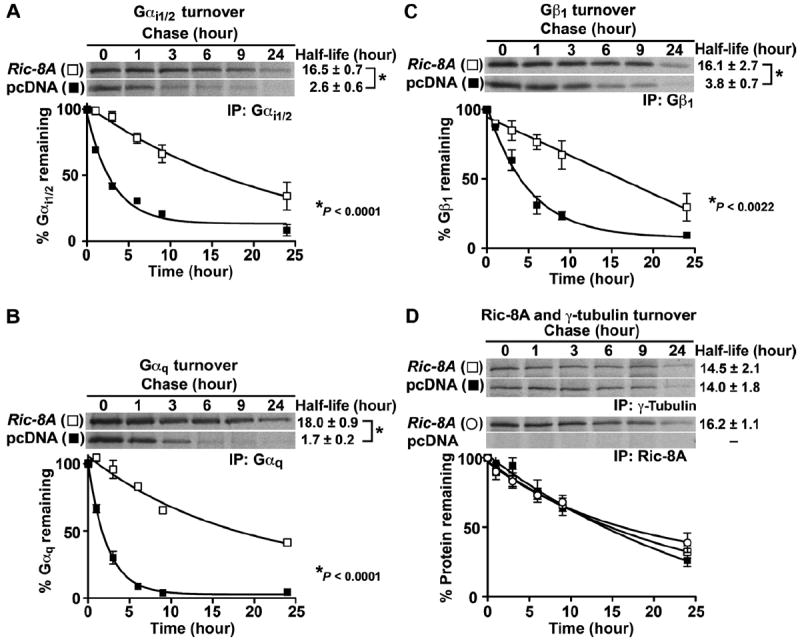

The large Ric-8A–dependent reductions in the steady-state amounts of Gα and total Gβ could be explained if the nascent Gα subunits that did not associate with the membrane were rapidly degraded. We measured the protein turnover rates of endogenous Gαi1/2, Gαq, and Gβ1 in Ric-8A−/− cells expressing Ric-8A (Tg) or sham cDNA. Cells were pulse-labeled for 60 min and chased over a 24-hour time course. Gαi1/2, Gαq, Gβ1, Ric-8A, and γ-tubulin were individually immunoprecipitated and visualized by SDS-PAGE or autoradiography (Fig. 5). The turnover rates of Gαi1/2 and Gαq were enhanced markedly in the Ric-8A–deleted cells, with half-lives (t1/2) of 2.6 ± 0.6 and 1.7 ± 0.2 hours compared to 16.5 ± 0.7 and 18 ± 0.9 hours, respectively, when Ric-8A was expressed. Gβ1 was also degraded faster in Ric-8A–deleted cells with a t1/2 of 3.8 ± 0.7 hours compared to 16.1 ± 2.7 hours in cells in which Ric-8A was expressed. An unrelated control protein, γ-tubulin was degraded with similar kinetics in both cell lines, and the t1/2 of Ric-8A turnover was 16.2 ± 1.1 hours. In the Ric-8A−/− cells, the substantial delay in Gβ1 turnover in comparison to that of Gα (Δt1/2 ~1.2 to 2.1 hours) may reflect the higher stability of Gβ1 compared to that of Gα, or it could delineate the sequence of events in the turnover of these proteins in the absence of Ric-8A.

Fig. 5.

Newly synthesized Gα subunits and Gβ1 are degraded rapidly in Ric-8A−/− mES cells. Ric-8A−/− cells stably expressing Ric-8A (Tg) or pcDNA were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine for 1 hour and chased in the presence of unlabeled amino acids for 0 to 24 hours. (A to D) Endogenous Gαi1/2 (A), Gαq (B), Gβ1 (C), and γ-tubulin (D) and stably expressed Ric-8A were immunoprecipitated at each time point, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography. The percentages of proteins that remained with time were quantified by pixel densitometry analysis as described earlier. The data were fit to monoexponential turnover functions to calculate half-lives with GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. Error bars represent the means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Basal and β-adrenergic–stimulated AC activities are attenuated in Ric-8A−/− and Ric-8B−/− mES cells

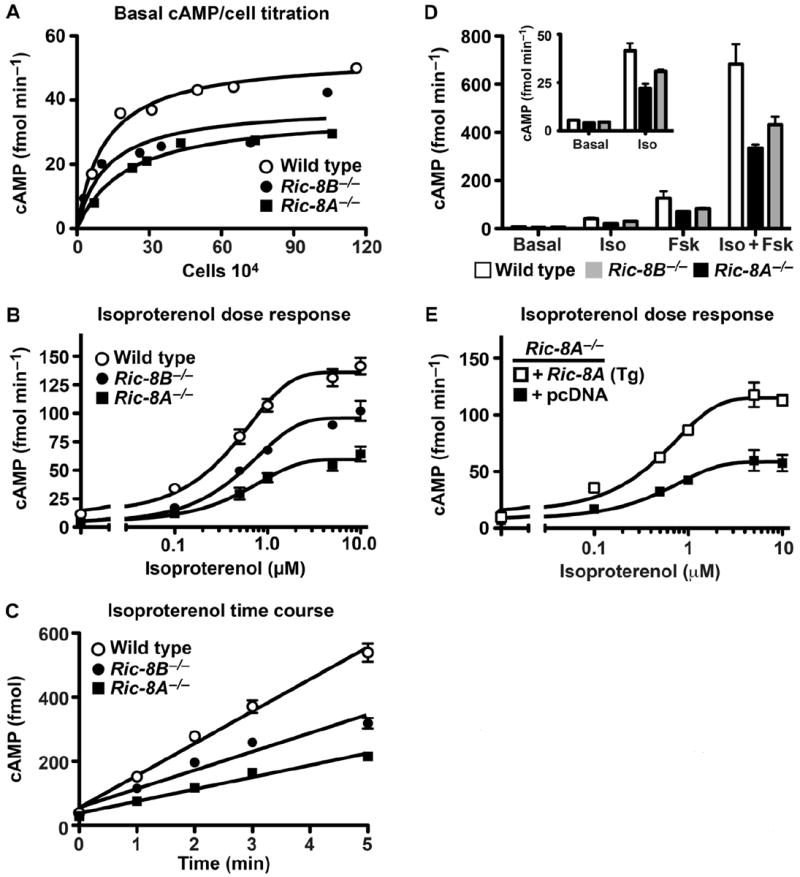

G protein allosteric modulators of AC enzymes include the stimulatory Gαs protein and the inhibitory Gαi protein, as well as Gβγ-specific regulation of AC isoforms (50). Ric-8A deletion resulted in reduced amounts of Gαi and total Gβ proteins and modestly lowered amounts of membrane-bound Gαs, whereas deletion of Ric-8B affected the abundance of Gαs alone. We measured total AC activity in duplicate wild-type and Ric-8–null mES cell lines. Basal amounts of adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP) in Ric-8B−/− and Ric-8A−/− were lower than that in wild-type cells (Fig. 6A). Stimulation of wild-type, Ric-8A−/−, and Ric-8B−/− cells with a β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) agonist produced a similar result. The maximal amounts of isoproterenol-induced cAMP were lower in Ric-8B–null cells than in wild-type cells, but were most reduced in Ric-8A–null cells. Isoproterenol was equipotent in each of the three cell types [median effective concentration (EC50) range of ~410 to 515 nM], suggesting that the observed dysregulation of cAMP accumulation did not occur at the level of β-ARs in the absence of Ric-8A or Ric-8B (Fig. 6B). The defects were manifested in the initial phase of cAMP accumulation because a saturating concentration of isoproterenol (10 μM) in the presence of phosphodiesterase inhibitors stimulated wild-type cells to accumulate cAMP at the fastest rate (100 fmol/min) and Ric-8A−/− cells to accumulate cAMP at the slowest rate (38 fmol/min), whereas Ric-8B−/− cells produced cAMP at an intermediate rate (58 fmol/min) (Fig. 6C). Treatment of mES cells with forskolin, a direct activator of AC, recapitulated the results observed with isoproterenol. Forskolin potency was largely unaffected by Ric-8A or Ric-8B deletion, but the maximal response to forskolin was blunted the most in Ric-8A−/− cells and to an intermediate extent in Ric-8B−/− cells (Fig. 6D and fig. S4). We observed the known synergism between forskolin and isoproterenol in each cell type, but similar overall patterns of cAMP accumulation persisted.

Fig. 6.

Basal and β-AR–stimulated AC activity is attenuated in Ric-8A– and Ric-8B–deleted mES cells. (A) Wild-type, Ric-8A−/−, and Ric-8B−/− (1 × 104 to 75 × 104) mES cell lines were seeded in duplicate 96-well plates 24 hours before basal cAMP measurements were made. Cell counts were determined from one parallel plate at the time of basal cAMP measurement. Results are the average of two independent experiments from duplicate cell lines of each genotype. (B) Accumulated cAMP was measured after treatment of cells with isoproterenol (0 to 10 μM) for 2 min at 22°C. Error bars represent the means ± SEM for three independent experiments with duplicate cell lines of each genotype. (C) Accumulated cAMP was measured after cell treatment with a saturating concentration of isoproterenol (10 μM) for the indicated times at 22°C. Error bars represent the means ± SEM for three independent experiments with duplicate cell lines of each genotype. (D) Basal and accumulated cAMP amounts were measured after cell treatment with vehicle (basal), isoproterenol (100 nM, EC20), forskolin (50 μM, EC20), or isoproterenol and forskolin (EC20s) for 5 min at 22°C. Error bars represent the means ± SEM for three independent experiments with duplicate cell lines of each genotype. (E) Induction of cAMP accumulation by isoproterenol (0 to 10 μM) was measured in Ric-8A−/− mES cell lines stably transfected with Ric-8A cDNA (Tg) or sham vector. Error bars represent the means ± SEM for three independent experiments.

The dose-dependent relationship between isoproterenol and cAMP accumulation in the Ric-8A−/− mES cell line genetically complemented with Ric-8A (Tg) or expressing sham cDNA showed that stable Ric-8A expression rescued the defect in cAMP accumulation in Ric-8A–null cells (Fig. 6E). In summary, basal as well as hormone- and forskolin-stimulated cAMP amounts were most depressed in Ric-8A−/− cell lines and to an intermediate extent in the Ric-8B−/− cell lines. The simplest interpretation of these reductions in the amounts of cAMP in Ric-8B−/− cells is that they are a result of the ~85% loss in the abundance of the AC activator, Gαs. It is not intuitively clear why cAMP concentrations were further depressed in Ric-8A–null cells because these cells expressed substantially more Gαs and less Gαi than did the Ric-8B−/− cells. The pronounced reduction in the amount of total G proteins, particularly steady-state Gβγ abundance in the Ric-8A−/− cells, may have contributed to the reduced total AC activities. Alternatively, misregulation at the level of AC enzyme(s) or combinatorial effects thereof with the reduced G protein amounts seems likely.

Lysophosphatidic acid receptor–dependent and Rho-dependent modulation of F-actin amounts and structure are perturbed in Ric-8A–null mES cells

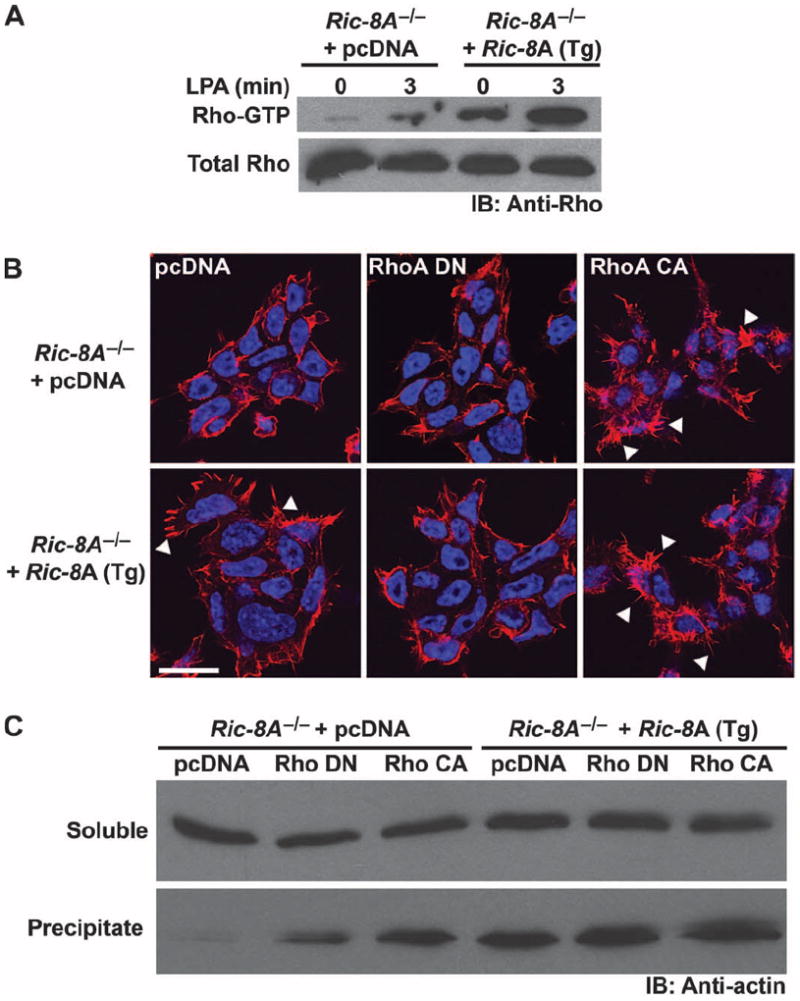

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) receptors activateG12/13 family G proteins, whose Gα12 and Gα13 subunits in turn bind to p115 Rho GEFs to activate Rho family guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) (51). Activated Rho signals to alter the actin cytoskeleton and the adhesive properties of cells. Ric-8A stimulates guanine nucleotide exchange on Gα13 (1), and we found that it was required for optimal Gα13 abundance (Fig. 2). Whole-cell actin and precipitable actin (F-actin) were also reduced 40 and 70%, respectively, in Ric-8A−/− cells, but not in Ric-8B−/− cells (Figs. 1B and 2A). To test whether the defect in F-actin was attributed to aberrant G12/13-mediated regulation of Rho signaling, we measured basal (continuous serum only) and LPA-stimulated amounts of Rho-GTP by glutathione S-transferase (GST)–Rhotekin pull-down assays in Ric-8A−/− mES cells that stably expressed Ric-8A (Tg) or sham cDNA (Fig. 7A). We found that the total amounts of Rho in these cells were equivalent, but that the basal amount of Rho-GTP was markedly reduced in the Ric-8A−/− cells compared to that in the Ric-8A–complemented Ric-8A−/− cells. The percentage increase in LPA-stimulated production of Rho-GTP over basal amounts was similar in both cell types, but LPA-induced Rho-GTP amounts were substantially higher in Ric-8A−/− cells than in Ric-8A−/− cells complemented with Ric-8A cDNA.

Fig. 7.

Basal and LPA receptor–stimulated Rho signaling is attenuated in Ric-8A–deleted mES cells. (A) Ric-8A−/− cells stably expressing Ric-8A or sham cDNA were not stimulated or were stimulated with LPA (10 μM) for 3 min. Rho-GTP was isolated from equivalent amounts of cell lysates in GST-Rhotekin pull-down assays. Relative amounts of total Rho and Rho-GTP were visualized by Western blotting with an antibody against Rho (Anti-Rho). Data are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Ric-8A−/− cells stably expressing Ric-8A (Tg) or sham cDNA were transiently transfected with control plasmid (pcDNA), plasmid encoding dominant-negative (DN) RhoA T19N, or plasmid encoding constitutively active (CA) RhoA G14V. After 48 hours, cells were costained with DAPI and rhodamine-phalloidin to visualize nuclei and F-actin structures, respectively. Arrowheads denote actin filopodia. Scale bar, 20 μm. Data are representative of three or more independent experiments. (C) Ric-8A−/− cells stably expressing Ric-8A (Tg) or sham cDNA were transiently transfected with pcDNA, RhoA (DN), or RhoA (CA) and fractionated by centrifugation of postnuclear supernatants at 150,000g. Relative amounts of G-actin and F-actin were visualized by Western blotting analysis with antibody against actin (Anti-actin). Data are representative of two independent experiments.

We then transiently transfected the cell lines with plasmids encoding dominant-negative or constitutively active RhoA proteins and incubated the cells with rhodamine-phalloidin to visualize actin microfilaments and filopodia by microscopy (Fig. 7B). Sham-transfected Ric-8A−/− cells had reduced amounts of actin microfilaments and filopodia-like structures compared to those of Ric-8A−/− cells stably expressing Ric-8A cDNA (Tg). Expression of dominant-negative RhoA reduced the numbers of phalloidin stained actin structures in the Ric-8A–expressing cells, whereas constitutively active RhoA increased the numbers of such structures in both cell types. Fractionation of total soluble G-actin from precipitable F-actin corroborated the microscopic analysis. The amounts of G-actin were unchanged, but substantially less F-actin was present in the Ric-8A–null cells than was in the Ric-8A–expressing cells (Fig. 7C). Constitutively active RhoA restored the deficit in F-actin observed in Ric-8A−/− cells. Signaling downstream of Rho was not perturbed in Ric-8A−/− cells, which implied that the misregulation of the actin cytoskeleton was at the level of Rho activation. Likely candidates of this misregulation include Gα12/13 and Gαq subunits because these G proteins activate Rho GEFs and were reduced in abundance >95% in Ric-8A−/− cells relative to wild-type cells.

DISCUSSION

Here, we found that Ric-8 GEFs were molecular chaperones that directed the initial association of nascent G protein α subunits with intracellular membranes. In cultured mES cell lines with deletions of Ric-8A or Ric-8B, we observed marked reductions in the steady state abundances of G protein α subunits. In Ric-8A–null cells, substantial portions of newly synthesized α subunits remained soluble and were degraded rapidly. Weak plasma membrane staining of transiently expressed G protein subunits persisted in the Ric-8–deficient cells. The basic scheme of the plasma membrane trafficking pathway remained intact for the small portion of nascent G proteins that became associated with intracellular membranes.

Reduced amounts of G proteins in Ric-8A– or Ric-8B–null cells resulted in GPCR signaling defects. We examined AC activity because control of this effector system by Gαi and Gαs is well characterized, and Ric-8A and Ric-8B act with exclusivity as GEFs and binding partners for these respective G proteins. Ric-8A–null cells had the lowest basal, β-AR agonist–, and forskolin-stimulated AC activities. Ric-8B–null cells had only partially depressed AC activities despite having the least amount of Gαs. The greater loss of total AC activity in Ric-8A–null cells was unexpected and may have been a consequence of the substantial partial loss of total Gβ, which would reduce the efficiency of functional coupling between the GPCR and Gαs. Misregulation of additional signaling inputs, including reductions in the abundance or function of AC, is a plausible possibility in Ric-8–deleted cells and merits further examination. It is clear that the near-complete loss of Gαi class subunits in Ric-8A–null cells and thus the relief of tonic Gαi-mediated inhibition of AC was far less consequential toward total cellular AC activities than were the 20 and 40% reductions in the amounts of membrane Gαs and total Gβγ, respectively, in addition to any potential misregulation of AC that might have occurred.

The cause of the reduction in the amount of Gβγ in Ric-8A–null, but not Ric-8B–null, cells was secondary to the reduced bulk steady-state amounts of Gα subunits (the Gαi class being the most abundant). In HeLa cells, short interfering RNA (siRNA)–mediated silencing of Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3 resulted in a 50% reduction in the amount of total Gβ (52). Extending this logic, the 20% reduction in the amount of membrane Gαs in Ric-8A–null cells would be a tertiary consequence of the ~40% loss of the total Gβ pool, because Ric-8A is not a GEF for Gαs and does not bind to this subunit. Furthermore, the deficit in membrane Gαs was rescued by overexpression of Gβ1 and Gγ2 in Ric-8A−/− cells, but not in Ric-8B−/− cells. In summary, the primary defects in G protein α subunit abundance in Ric-8A– or Ric-8B–deleted mES cells are consistent with the known enzymatic and binding preferences that Ric-8A and Ric-8B have for distinct subsets of the G protein α subunit classes, with Ric-8A binding to Gαi, Gαq, andGα12/13, whereas Ric-8B binds to Gαs.

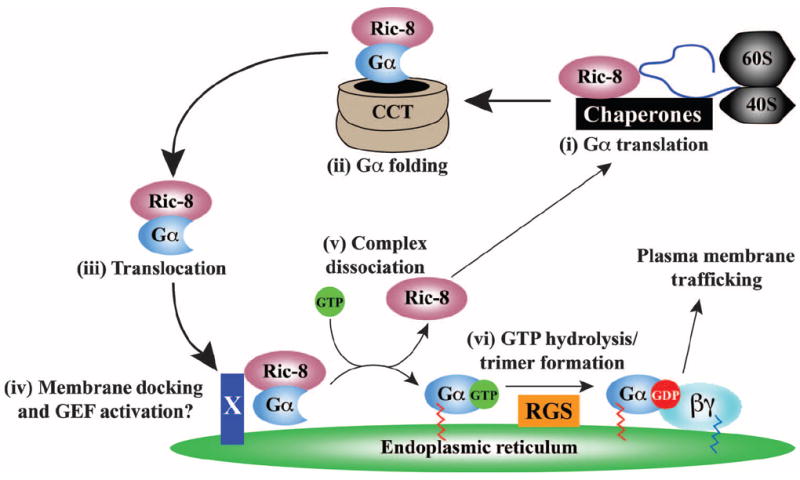

Our study prompts the question of how the GEF activity of Ric-8 regulates the membrane attachment of newly synthesized Gα subunits. We propose that Ric-8 GEF activity may not necessarily (or always) be for the purpose of producing activated Gα-GTP to evoke signaling outputs (1). Rather, Ric-8 may make use of the G protein guanine nucleotide switch as a means to become dissociated from Gα. Ric-8 proteins preferentially bind to nucleotide-free G protein α subunits, and they become dissociated upon binding of GTP to Gα. Nascent Gα subunit protein chains that emerge from ribosomes are not bound to guanine nucleotide until they fold properly and develop a guanine nucleotide–binding pocket. If Ric-8 binds to a G protein α subunit that is emerging fromthe ribosome, it could assist the folding or presentation of the unfolded Gα protein chain to the CCT (Fig. 8). Analogous to the actions of PhLP-1 and Gβ, Ric-8 could form a ternary complex with Gα and CCT during folding of the G protein α subunit (Fig. 8) and subsequently act as the escort chaperone to shuttle the nascent, nucleotide-free G protein α subunit to an ER-docking site (Fig. 8). At the ER, Ric-8 could be stimulated to induce nucleotide exchange and release free Gα-GTP onto the membrane (Fig. 8). Subsequent GTP hydrolysis by Gα may occur intrinsically or may be aided by the GTPase-activating activity of an endomembrane-specific regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) protein (Fig. 8). Gα-GDP would then be primed to bind to free Gβγ and assemble a nascent G protein heterotrimer before it is targeted to the plasma membrane.

Fig. 8.

Proposed model for the action of Ric-8 during G protein biosynthesis. Gα subunits are translated on free, cytosolic ribosomes. (i) The emerging Gα chain may be bound by Ric-8 and cellular chaperones during initial protein folding, or (ii) it may be folded as part of a ternary complex withCCTand Ric-8. (iii) The nucleotide-free Ric-8–Gα complex then translocates to a putative, ER membrane–specific docking factor (X) that may also serve as the cellular activator (iv) of Ric-8 nucleotide exchange stimulatory activity, enabling production of (v) dissociated Ric-8 and membrane-bound Gα-GTP. (vi) Gα hydrolyzes GTP, perhaps through the aid of organelle-specific RGS GAPs (GTPase-activating proteins). The resultant Gα-GDP binds to Gβγ before the newly formed G protein heterotrimer traffics to the plasma membrane.

Here, we have defined a specific role for Ric-8 proteins as molecular chaperones that regulate G protein biosynthesis. This role provides an explanation of how Ric-8 proteins seemingly regulate diverse G protein signaling outputs in worms, flies, and mammals. Other roles for Ric-8–mediated regulation of G proteins in cells should not be overlooked. Ric-8A and C. elegans RIC-8 are recruited to the growing mitotic spindle and may work with Gαi and GPR/GoLoco-containing proteins to regulate spindle positioning during cell division (9, 12). Documented localization of Ric-8A at the spindle is not intuitively consistent with an exclusive role for Ric-8A as a chaperone that regulates the biosynthesis of G protein α subunits. A study found that Ric-8B is recruited to the plasma membrane upon chronic stimulation with high concentrations of GPCR agonists (53). In that study, the plasma membrane–docking site for Ric-8B was not shown but was inferred to be G protein α subunits dissociated from Gβγ dimers. Mature G proteins are thought to transit diffusively among the plasma membrane and endomembranes. Perhaps, additional roles for Ric-8 proteins as escort chaperones for G protein α subunits in trafficking pathways distinct from initial biosynthesis exist and remain to be explored.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents, antibodies, and plasmids

Rabbit polyclonal antiserum 2414 against Ric-8B was produced by Capralogics Inc., using purified full-length Ric-8B protein as an immunogen. Rabbit polyclonal antiserum against Ric-8A was used to detect Ric-8A protein (54). G protein subunit–specific antisera were used to detect Gαi1/2 (BO84), Gβ1-4 (B600) (55), Gαo (S214), Gαs (584), Gβ1 (U49) (48), Gαq (WO82, Z811, and Z808) (56, 57), and Gα13 (B860) (58). Antibodies against actin, α-tubulin, γ-tubulin, and Oct3/4 were from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. Antibody against glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. Antibody against Rho (clone 55) was from Millipore. cDNA encoding human Ric-8A was subcloned by linker-based PCR from HeLa cell cDNA into the Nhe I and Not I sites of pcDNA3.1/Hygro or pcDNA3.1/Neo. Plasmids encoding Gαi-GFP and Gαq-GFP were gifts from A. Smrcka and S. Malik. Plasmids encoding GαsL-YFP, YFP–N-β1, and YFP–C-γ7 were gifts from C. Berlot (47, 59). cDNAs encoding human Glu-Glu–tagged Gαi1, FLAG-Gβ1, Gγ2, RhoT19N, and RhoG12V in pcDNA3.1/Neo (Invitrogen) were obtained from the S&T cDNA Resource Center. Sequences encoding wild-type and Glu-Glu–tagged G2A Gαi1 were amplified by PCR (using a mutant sense strand primer to create G2A) and subcloned into pcDNA3.1/Hygro (Invitrogen).

Engineering of mouse Ric-8A– and Ric-8B–null alleles

Targeted mES cells harboring null alleles of Ric-8A (VelociGene ID: VG #546) or Ric-8B (VelociGene ID: VG#547) were generated with VelociGene technology (44). Bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) containing mouse genomic DNA encompassing Ric-8A or Ric-8B were selected by a PCR-based screen from a 129/Svj mouse genomic DNA BAC library (Incyte). The BAC ID for Ric-8A was from BAC ES release 2: 109m11 and contained ~135 kb of genomic DNA. The BAC ID for Ric-8B was from BAC ES release 2: 292o14 and contained ~170 kb of genomic DNA. To generate the targeting vectors, we replaced a 4961–base pair (bp) region of the Ric-8A locus consisting of the entire coding sequence with a transmembrane domain–LacZ/Neomycin phosphotransferase (TM-LacZ/Neo)–encoding cassette by bacterial homologous recombination (BHR) (60-63). An ~30,689-bp region spanning the first three exons and a portion of the third intron of the Ric-8B locus was also replaced with this cassette. In preparation for targeting, the modified BACswere subjected to restriction digest with Not I to generate linear targeting vectors with BAC homology arms of about 40 and 95 kb, for Ric-8A, or 50 and 100 kb, for Ric-8B, flanking the TM-LacZ/Neo cassettes. The ES line F1H4, a C57BL/6-129SvJ hybrid, was electroporated with the linearized constructs. 288 Ric-8A and 288 Ric-8B ES cell clones were selected and genotyped by loss-of-allele (LOA) assays (44). Seventeen of 288 Ric-8A clones and 8 of 288 Ric-8B clones were targeted, indicating targeting frequencies of 5.9 and 2.8%, respectively. Mice were generated by microinjection of the targeted ES cells into C57BL/6 blastocysts and backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice.

Derivation and culture of mES cell lines

Three- to 5-week-old Ric-8A+/− or Ric-8B+/− (C57BL/6) mice were superovulated by intraperitoneal injection of 5 IU of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG), whichwas followed 48 hours later by injection of 5 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (Sigma-Aldrich). Mice were mated and, 48 hours after fertilization, were injected intraperitoneally with 0.1 mg of tamoxifen and subcutaneously with 3 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent blastocyst implantation. After 4 days (delayed ~E6.5), pregnant mice were killed, uteri and oviducts were dissected, and blastocysts were flushed out with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) buffered with 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4) (Invitrogen). Blastocysts were cultured individually on 0.1% gelatin–coated plates in RESGRO medium (Millipore). After 2 days of growth, inner cell masses were mechanically detached and subcultured in RESGRO medium. Derived mES cell lines were maintained in ES cell medium [DMEM containing 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1× nonessential amino acid mixture (Invitrogen), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and recombinant leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (10 μg/ml; Millipore)]. MEFs were isolated from E14.5 wild-type C57BL/6 mouse embryos as described previously (64). To assess β-galactosidase activity in stem cells, we washed the cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed them with 0.2% glutaraldehyde, and stained them in 2 μM MgCl2, 4 μM ferrous cyanide, 4 μM ferric cyanide, and X-galactosidase (0.5 mg/ml) in PBS at 37°C for up to 2 hours.

AC assays

In standard assays, 4 × 104 ES cells were seeded per well in 96-well plates 24 hours before commencement of the assay. For the basal cAMP cell titration experiment, 1 × 104 to 75 × 104 cells were seeded per well. The medium was exchanged with DMEM containing 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 0.1 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX), 0.1 mM rolipram, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for all experiments. For the isoproterenol time course experiment, cells were incubated with isoproterenol (10 μM) for 0 to 5 min at 22°C. For the isoproterenol dose-response experiments, cells were incubated with isoproterenol (0 to 10 μM) for 2 min at 22°C. To measure the combined effects of forskolin and isoproterenol, we incubated cells with isoproterenol (100 nM) with or without soluble forskolin (50 μM, Tocris Bioscience) for 5 min at 22°C. Reactions were quenched with the LANCE cAMP Detection Kit lysis reagent (PerkinElmer), and the accumulated cAMP was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions with a Victor 3V plate reader (PerkinElmer). Signals were measured at 615 and 665 nm.

Measurements of Rho-GTP and F-actin abundance

Cells were either left untreated or treated with oleoyl-l-α-lysophosphatidic acid (LPA, 10 μM; Avanti Polar Lipids Inc.) for 3 min and lysed in the lysis/binding/wash buffer supplied in the EZ-Detect Rho Activation Kit (Pierce). Total protein was quantified by Amido Black Protein Assay (65). Equivalent samples were supplemented with GST-Rhotekin RBD, and Rho-GTPwas isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce). Total Rho and Rho-GTP were visualized by Western blotting analysis with an antibody against Rho that detected Rho protein (clone 55, Millipore). ES cells grown on gelatin-coated glass were rinsed in PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldeyhyde (PFA), blocked with 5% BSA in PBS, and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin (0.25 U/ml; Invitrogen) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (0.1 μg/ml; Invitrogen). F-actin structures and nuclei were imaged by confocal microscopy with a 60× oil immersion objective [numerical aperture (NA) = 1.35]. For fractionation of F-actin and G-actin, cells were lysed by nitrogen cavitation (Parr Industries), and lysates were centrifuged at 150,000g for 60 min. Laemmli sample buffer was added to the soluble and precipitate fractions. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with an antibody against actin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from feeder-free ES cells with the RNA queous RNA isolation kit (Ambion). RNA was converted to cDNA with a Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). PCR assays (each containing 20 μl of reaction volume) were performed in triplicate with an ABI Prism 7000 Real-Time PCR cycler (Invitrogen) and consisted of 1 μg of cDNA, uniquely designed combinations of TaqMan probes and primers (Roche Universal Probe Library Assay Design Center), and FastStart Universal Probe Master Mix with ROX (Roche). The relative amounts of mRNAs in the Ric-8 knockout cell line compared to those in wild-type cells were calculated with the ΔΔCt method (66) and an actin reference gene TaqMan assay. All TaqMan assays were verified to be >85% efficient.

Metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitations

Feeder-free ES cells were grown in gelatin-coated dishes and starved in cysteine- and methionine-free DMEM (Mediatech Inc.) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 1× nonessential amino acid mixture (Invitrogen), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 15% dialyzed FBS (Invitrogen) for 20 to 45 min. Cells were metabolically pulse-labeled at 37°C in this medium supplemented with l-[35S]cysteine and l-[35S]methionine (200 to 300 μCi/ml; EXPRE35S35S Protein Labeling Mix, PerkinElmer) for the indicated times. Cells subjected to chase were washed once and incubated at 37°C in chase medium (ES cell medium without LIF, supplemented with 1 mM l-cysteine and 1 mM l-methionine). For biosynthesis and coimmunoprecipitation experiments, labeled cells (from ~90% confluent 60-mm dishes) were washed with ice-cold PBS and solubilized in PBS containing 2% NP-40, 1 μM GDP, and a mixture of protease inhibitors [phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (23 μg/ml), Nα-tosyl-l-lysine-chloromethyl ketone (21 μg/ml), l-1-p-tosylamino-2-phenylethyl-chloromethyl ketone (21 μg/ml), leupeptin (3.3 μg/ml), and lima bean trypsin inhibitor (3.3 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich)]. Clarified detergent lysates were incubated with antisera for 18 hours at 4°C followed by incubation with Protein A–Agarose (Roche) for 4 hours at 4°C. Protein A–captured antibody-antigen complexes were solubilized in Laemmli sample buffer and resolved on 12% tris-glycine-SDS gels. Gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography. For subcellular fractionation pulse-chase labeling experiments, labeled cells (from two ~90% confluent 10-cm dishes) were lysed by nitrogen cavitation in fractionation lysis buffer (PBS containing 1 mM EDTA, 1 μM GDP, and protease inhibitor mixture). The postnuclear 500g supernatants were centrifuged at 150,000g for 30 min. Soluble fractions were supplemented with 1% sodium cholate and 1% NP-40, precleared with Protein A–Agarose, and subjected to immunoprecipitation as described earlier. Crude membrane fractions were dounce-homogenized in fractionation lysis buffer containing 1% sodium cholate and 1% NP-40 and rotated for 10 min at 22°C to extract proteins. The membrane extracts were clarified by centrifugation and subjected to immunoprecipitation. For protein turnover measurements, metabolically labeled cells (from ~90% confluent 60-mm dishes) were lysed in cholate lysis buffer [40 mM tris (pH 7.7), 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 1% sodium cholate, BSA (100 μg/ml), and protease inhibitor mixture] and clarified by centrifugation at 21,000g. To immunoprecipitate partially denatured individual antigens (Gαi1/2, Gαq, Gβ1, Ric-8A, and γ-tubulin), we added SDS (0.5%) and Triton X-100 (1%) and precleared the supernatants with Protein A–Agarose before immunoprecipitation.

Cell imaging

For Oct3/4 immunofluorescence experiments, cells seeded on coverslips were rinsed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA in PBS for 20 min at 22°C. Fixed cells were treated with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, blocked in 5% BSA in PBS, and incubated with antibody against Oct3/4. Cells were washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated antibody against mouse antibody (Invitrogen). Washed cells were stained with DAPI, mounted, and imaged with a Nikon TE200 inverted microscope with 10× or 20× objective lenses coupled to a monochrometer-based epifluorescence illumination system (TILL Photonics). Excitation was performed at 405 and 568 nm, and images were captured with a high-speed, digital charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (TILL Photonics). To image live cells that were transfected with plasmids encoding fluorescently tagged G protein subunits, we exchanged the cell medium with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS). Cells were imaged on an Olympus BX61WI upright microscope coupled to an Olympus Fluoview 1000 multiphoton/confocal (FV1000MP) microscope equipped with a suite of diode and gas lasers. Imaging was performed with a 60× water immersion objective (NA = 0.9).

Statistical analysis

Error bars represent the SEM for at least three independent experiments as indicated throughout. Two-tailed unpaired t tests with confidence intervals of 95% were conducted as indicated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Yule for discussions and expert microscopy consultation, A. Smrcka for discussions, R. Tall for qPCR expertise and assay design, and T. O’Leary for technical assistance.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grant GM088242 (to G.G.T.) and New York State Stem Cell Science grant C024307 (to G.G.T.). M.E.P. received support from the Summer Scholar REU Site Program in Cellular and Molecular Biology at Rochester (0755117, NSF/Division of Biological Infrastructure).

Footnotes

Author contributions: M.G., M.E.P., F.A.W., and G.G.T. performed the experiments; A.J.M., D.M.V., and G.D.Y. designed and created Ric-8A and Ric-8B transgenic mice; and M.G., P.C., and G.G.T. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencesignaling.org/cgi/content/full/4/200/ra79/DC1

Fig. S1. Genomic PCR scheme to genotype Ric-8A– and Ric-8B–deleted mice and derived mES cell lines.

Fig. S2. Increased abundance of Gβγ does not rescue the defects in Gα protein abundance observed in Ric-8−/− cells.

Fig. S3. Nascent Gαi appears to be differentially modified in Ric-8A−/− and wild-type cells by means other than myristoylation.

Fig. S4. Forskolin-stimulated cAMP production is blunted in Ric-8A−/− and Ric-8B−/− cells compared to that in wild-type cells.

Competing interests: A.J.M., D.M.V., and G.D.Y. are employees of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Use of the Ric-8A– or Ric-8B–null mice requires a materials transfer agreement (MTA) from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Chan P, Gabay M, Wright FA, Tall GG. Ric-8B is a GTP-dependent G protein αs guanine nucleotide exchange factor. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19932–19942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.163675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tall GG, Krumins AM, Gilman AG. Mammalian Ric-8A (synembryn) is a heterotrimeric Gα protein guanine nucleotide exchange factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8356–8362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller KG, Alfonso A, Nguyen M, Crowell JA, Johnson CD, Rand JB. A genetic selection for Caenorhabditis elegans synaptic transmission mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12593–12598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller KG, Emerson MD, McManus JR, Rand JB. RIC-8 (synembryn): A novel conserved protein that is required for Gqα signaling in the C. elegans nervous system. Neuron. 2000;27:289–299. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00037-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller KG, Rand JB. A role for RIC-8 (synembryn) and GOA-1 (Goα) in regulating a subset of centrosome movements during early embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2000;156:1649–1660. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.4.1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds NK, Schade MA, Miller KG. Convergent, RIC-8-dependent Gα signaling pathways in the Caenorhabditis elegans synaptic signaling network. Genetics. 2005;169:651–670. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.031286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afshar K, Willard FS, Colombo K, Johnston CA, McCudden CR, Siderovski DP, Gönczy P. RIC-8 is required for GPR-1/2-dependent Gα function during asymmetric division of C. elegans embryos. Cell. 2004;119:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couwenbergs C, Spilker AC, Gotta M. Control of embryonic spindle positioning and Gα activity by C. elegans RIC-8. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1871–1876. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hess HA, Röper JC, Grill SW, Koelle MR. RGS-7 completes a receptor-independent heterotrimeric G protein cycle to asymmetrically regulate mitotic spindle positioning in C. elegans. Cell. 2004;119:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuzaki F. Drosophila G-protein signalling: Intricate roles for Ric-8? Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1047–1049. doi: 10.1038/ncb1105-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tall GG, Gilman AG. Resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 8A catalyzes release of Gαi-GTP and nuclear mitotic apparatus protein (NuMA) from NuMA/LGN/Gαi-GDP complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16584–16589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508306102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodard GE, Huang NN, Cho H, Miki T, Tall GG, Kehrl JH. Ric-8A and Giα recruit LGN, NuMA, and dynein to the cell cortex to help orient the mitotic spindle. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3519–3530. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00394-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr DS, Von Dannecker LEC, Davalos M, Michaloski JS, Malnic B. Ric-8B interacts with Gαolf and Gγ13 and co-localizes with Gαolf, Gβ1 and Gγ13 in the cilia of olfactory sensory neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishimura A, Okamoto M, Sugawara Y, Mizuno N, Yamauchi J, Itoh H. Ric-8A potentiates Gq-mediated signal transduction by acting downstream of G protein-coupled receptor in intact cells. Genes Cells. 2006;11:487–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Dannecker LEC, Mercandante AF, Malnic B. Ric-8B, an olfactory putative GTP exchange factor, amplifies signal transduction through the olfactory-specific G-protein Gαolf. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3793–3800. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4595-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Von Dannecker LEC, Mercadante AF, Malnic B. Ric-8B promotes functional expression of odorant receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9310–9314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600697103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhuang H, Matsunami H. Synergism of accessory factors in functional expression of mammalian odorant receptors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15284–15293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.David NB, Martin CA, Segalen M, Rosenfeld F, Schweisguth F, Bellaïche Y. Drosophila Ric-8 regulates Gαi cortical localization to promote Gαi-dependent planar orientation of the mitotic spindle during asymmetric cell division. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1083–1090. doi: 10.1038/ncb1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hampoelz B, Hoeller O, Bowman SK, Dunican D, Knoblich JA. Drosophila Ric-8 is essential for plasma-membrane localization of heterotrimeric G proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1099–1105. doi: 10.1038/ncb1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang H, Ng KH, Qian H, Siderovski DP, Chia W, Yu F. Ric-8 controls Drosophila neural progenitor asymmetric division by regulating heterotrimeric G proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1091–1098. doi: 10.1038/ncb1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afshar K, Willard FS, Colombo K, Siderovski DP, Gönczy P. Cortical localization of the Gα protein GPA-16 requires RIC-8 function during C. elegans asymmetric cell division. Development. 2005;132:4449–4459. doi: 10.1242/dev.02039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagai Y, Nishimura A, Tago K, Mizuno N, Itoh H. Ric-8B stabilizes the α subunit of stimulatory G protein by inhibiting its ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11114–11120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.063313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan P, Gabay M, Wright FA, Kan W, Oner SS, Lanier SM, Smrcka AV, Blumer JB, Tall GG. Purification of heterotrimeric G protein α subunits by GST-Ric-8 association: Primary characterization of purified Gαolf. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2625–2635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.178897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farr GW, Scharl EC, Schumacher RJ, Sondek S, Horwich AL. Chaperonin-mediated folding in the eukaryotic cytosol proceeds through rounds of release of native and nonnative forms. Cell. 1997;89:927–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wells CA, Dingus J, Hildebrandt JD. Role of the chaperonin CCT/TRiC complex in G protein βγ-dimer assembly. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20221–20232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dupré DJ, Robitaille M, Richer M, Ethier N, Mamarbachi AM, Hébert TE. Dopamine receptor-interacting protein 78 acts as a molecular chaperone for Gγ subunits before assembly with Gβ. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13703–13715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukov GL, Baker CM, Ludtke PJ, Hu T, Carter MD, Hackett RA, Thulin CD, Willardson BM. Mechanism of assembly of G protein βγ subunits by protein kinase CK2-phosphorylated phosducin-like protein and the cytosolic chaperonin complex. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22261–22274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukov GL, Hu T, McLaughlin JN, Hamm HE, Willardson BM. Phosducin-like protein acts as a molecular chaperone for G protein βγ dimer assembly. EMBO J. 2005;24:1965–1975. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehm A, Ploegh HL. Assembly and intracellular targeting of the βγ subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:305–317. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dupré DJ, Robitaille M, Rebois RV, Hébert TE. The role of Gβγ subunits in the organization, assembly, and function of GPCR signaling complexes. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:31–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-061008-103038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willardson BM, Howlett AC. Function of phosducin-like proteins in G protein signaling and chaperone-assisted protein folding. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2417–2427. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linder ME, Middleton P, Hepler JR, Taussig R, Gilman AG, Mumby SM. Lipid modifications of G proteins: α subunits are palmitoylated. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3675–3679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marrari Y, Crouthamel M, Irannejad R, Wedegaertner PB. Assembly and trafficking of heterotrimeric G proteins. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7665–7677. doi: 10.1021/bi700338m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mumby SM, Heukeroth RO, Gordon JI, Gilman AG. G-protein α-subunit expression, myristoylation, and membrane association in COS cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:728–732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones TL, Simonds WF, Merendino JJ, Jr, Brann MR, Spiegel AM. Myristoylation of an inhibitory GTP-binding protein α subunit is essential for its membrane attachment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:568–572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Preininger AM, Parello J, Meier SM, Liao G, Hamm HE. Receptor-mediated changes at the myristoylated amino terminus of Gαil proteins. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10281–10293. doi: 10.1021/bi800741r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes TE, Zhang H, Logothetis DE, Berlot CH. Visualization of a functional Gαq-green fluorescent protein fusion in living cells. Association with the plasma membrane is disrupted by mutational activation and by elimination of palmitoylation sites, but not by activation mediated by receptors or . J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4227–4235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ransnas LA, Svoboda P, Jasper JR, Insel PA. Stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors of S49 lymphoma cells redistributes the α subunit of the stimulatory G protein between cytosol and membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7900–7903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Svoboda P, Novotny J. Hormone-induced subcellular redistribution of trimeric G proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:501–512. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8441-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wedegaertner PB, Bourne HR, von Zastrow M. Activation-induced subcellular redistribution of Gsα. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1225–1233. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.8.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsutsumi R, Fukata Y, Noritake J, Iwanaga T, Perez F, Fukata M. Identification of G protein α subunit-palmitoylating enzyme. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:435–447. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01144-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chisari M, Saini DK, Kalyanaraman V, Gautam N. Shuttling of G protein subunits between the plasma membrane and intracellular membranes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24092–24098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704246200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tõnissoo T, Lulla S, Meier R, Saare M, Ruisu K, Pooga M, Karis A. Nucleotide exchange factor RIC-8 is indispensable in mammalian early development. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:3404–3415. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Frendewey D, Gale NW, Economides AN, Auerbach W, Poueymirou WT, Adams NC, Rojas J, Yasenchak J, Chernomorsky R, Boucher M, Elsasser AL, Esau L, Zheng J, Griffiths JA, Wang X, Su H, Xue Y, Dominguez MG, Noguera I, Torres R, Macdonald LE, Stewart AF, DeChiara TM, Yancopoulos GD. High-throughput engineering of the mouse genome coupled with high-resolution expression analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:652–659. doi: 10.1038/nbt822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nichols J, Zevnik B, Anastassiadis K, Niwa H, Klewe-Nebenius D, Chambers I, Schöler H, Smith A. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siderovski DP, Willard FS. The GAPs, GEFs, and GDIs of heterotrimeric G-protein α subunits. Int J Biol Sci. 2005;1:51–66. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hynes TR, Tang L, Mervine SM, Sabo JL, Yost EA, Devreotes PN, Berlot CH. Visualization of G protein βγ dimers using bimolecular fluorescence complementation demonstrates roles for both β and γ in subcellular targeting. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30279–30286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mumby SM, Kahn RA, Manning DR, Gilman AG. Antisera of designed specificity for subunits of guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:265–269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linder ME, Ewald DA, Miller RJ, Gilman AG. Purification and characterization of Goα and three types of Giα after expression in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:8243–8251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang WJ, Gilman AG. Adenylyl cyclases. Cell. 1992;70:869–872. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hart MJ, Jiang X, Kozasa T, Roscoe W, Singer WD, Gilman AG, Sternweis PC, Bollag G. Direct stimulation of the guanine nucleotide exchange activity of p115 RhoGEF by Gα13. Science. 1998;280:2112–2114. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krumins AM, Gilman AG. Targeted knockdown of G protein subunits selectively prevents receptor-mediated modulation of effectors and reveals complex changes in non-targeted signaling proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10250–10262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klattenhoff C, Montecino M, Soto X, Guzmán L, Romo X, de los Angeles García M, Mellstrom B, Naranjo JR, Hinrichs MV, Olate J. Human brain synembryn interacts with Gsα and Gqα and is translocated to the plasma membrane in response to isoproterenol and carbachol. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195:151–157. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malik S, Ghosh M, Bonacci TM, Tall GG, Smrcka AV. Ric-8 enhances G protein βγ-dependent signaling in response to βγ-binding peptides in intact cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:129–136. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.010116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mumby SM, Gilman AG. Synthetic peptide antisera with determined specificity for G protein α or β subunits. Methods Enzymol. 1991;195:215–233. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)95168-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gutowski S, Smrcka A, Nowak L, Wu DG, Simon M, Sternweis PC. Antibodies to the αq subfamily of guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory protein α subunits attenuate activation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis by hormones. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20519–20524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pang IH, Sternweis PC. Purification of unique α subunits of GTP-binding regulatory proteins (G proteins) by affinity chromatography with immobilized βγ subunits. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18707–18712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singer WD, Miller RT, Sternweis PC. Purification and characterization of the α subunit of G13. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19796–19802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hein P, Rochais F, Hoffmann C, Dorsch S, Nikolaev VO, Engelhardt S, Berlot CH, Lohse MJ, Bünemann M. GS activation is time-limiting in initiating receptor-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33345–33351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu Q, Li MZ, Leibham D, Cortez D, Elledge SJ. The univector plasmid-fusion system, a method for rapid construction of recombinant DNA without restriction enzymes. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1300–1309. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00560-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Narayanan K, Williamson R, Zhang Y, Stewart AF, Ioannou PA. Efficient and precise engineering of a 200 kb β-globin human/bacterial artificial chromosome in E. coli DH10B using an inducible homologous recombination system. Gene Ther. 1999;6:442–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang XW, Model P, Heintz N. Homologous recombination based modification in Escherichia coli and germline transmission in transgenic mice of a bacterial artificial chromosome. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:859–865. doi: 10.1038/nbt0997-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang Y, Buchholz F, Muyrers JPP, Stewart AF. A new logic for DNA engineering using recombination in Escherichia coli. Nat Genet. 1998;20:123–128. doi: 10.1038/2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagy A, Gertsenstein M, Vintersen K, Behringer R. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schaffner W, Weissmann C. A rapid, sensitive, and specific method for the determination of protein in dilute solution. Anal Biochem. 1973;56:502–514. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.