Abstract

BACKGROUND

There is limited information about the safety of chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease.

METHODS

This was a post hoc analysis from the INternational VErapamil Trandolapril STudy (INVEST), which enrolled patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease. At each visit, patients were asked by the local site investigator if they were currently taking NSAIDs. Patients who reported NSAID use at every visit were defined as chronic NSAID users, while all others (occasional or never users) were defined as nonchronic NSAID users. The primary composite outcome was all-cause death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke. Cox regression was used to construct a multivariate analysis for the primary outcome.

RESULTS

There were 882 chronic NSAID users and 21,694 nonchronic NSAID users (n = 14,408 for never users and n = 7286 for intermittent users). At a mean follow-up of 2.7 years, the primary outcome occurred at a rate of 4.4 events per 100 patient-years in the chronic NSAID group, versus 3.7 events per 100 patient-years in the nonchronic NSAID group (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.47; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19–1.82; P = .0003). This was due to an increase in cardiovascular mortality (adjusted HR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.70–3.01; P = .0001).

CONCLUSION

Among hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease, chronic self-reported use of NSAIDs was associated with an increased risk of adverse events during long-term follow-up.

Keywords: Coronary artery disease, Hypertension, Myocardial infarction, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs

Clinical trials and systematic reviews have shown that selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors increase the hazard for myocardial infarction.1–6 This finding likely resulted in more frequent use of nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as an alternative for chronic pain syndromes; however, current data are incomplete in regard to the cardiovascular safety profile of these agents.7,8

Among patients with a low prevalence of coronary artery disease and aspirin use, studies have consistently documented increased cardiovascular risk with diclofenac.9–11 Naproxen and ibuprofen are generally regarded as safer agents;12 however, a network meta-analysis in over 100,000 patients documented the highest risk for stroke with ibuprofen.13 Also, a randomized trial designed to prevent Alzheimer’s dementia with the use of NSAIDs was terminated early due to a possible excess in cardiovascular events with naproxen.14

In patients with established coronary artery disease, aspirin is unequivocally beneficial;15 however, data about concomitant use of aspirin and NSAIDs are limited. In one study, the use of aspirin plus ibuprofen (at least 1200 mg daily) after an acute myocardial infarction was associated with a 2.2-fold increase in mortality, despite a relatively short duration of use (median 37 days).16 A brief report in post-myocardial infarction patients also documented increased mortality with aspirin plus ibuprofen;17 however, another report found no effect on mortality.18

In summary, the current database is incomplete regarding the long-term safety of NSAIDs, especially among patients with coronary artery disease. Additionally, most of these studies were not designed to capture or control blood pressure during follow-up, and furthermore, they lacked appropriate prospective cardiovascular outcome data capture and adjudication. The INternational VErapamil Trandolapril STudy (INVEST) provided an opportunity to further investigate the association between chronic NSAID use, on-treatment blood pressure, and adverse outcomes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the association between chronic NSAID use, blood pressure, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes among hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease within the INVEST.

METHODS

Original Study Protocol

INVEST was an international randomized trial conducted in 14 countries that compared the effects of a calcium antagonist (verapamil SR)-based strategy with a beta-blocker (atenolol)-based strategy for hypertension among patients with stable coronary artery disease. Enrollment was from September 1997 to February 2003. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Local ethics committees approved the protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The main outcomes have been previously reported.19 Patients at least 50 years of age with hypertension and clinically stable coronary artery disease were eligible for enrollment. Protocol-scheduled follow-up visits occurred every 6 weeks for the first 6 months and then biannually until 2 years after the last patient was enrolled.

Post Hoc Analysis/Outcomes

At baseline and every follow-up visit, patients were asked if they were currently taking aspirin (yes or no) and NSAID medications (yes or no). These data were recorded by the local site physician investigator. We categorized NSAID exposure into chronic use (defined as individuals who reported NSAID use at baseline and each follow-up visit) versus nonchronic use (defined as individuals who never took NSAIDS or reported use at only some visits).

The primary outcome was the first occurrence of all-cause mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke. Secondary individual outcomes were all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, total myocardial infarction (nonfatal plus fatal myocardial infarctions), and total stroke (nonfatal plus fatal strokes). Outcomes were adjudicated by a blinded events committee by review of pertinent patient records, hospital records, and death registries.

To further assess the long-term cumulative effect of chronic NSAIDs on all-cause mortality, we searched the national death index among United States (US) patients up to 5 years after INVEST follow-up was concluded. To be considered a confirmed death, 4 of 5 matches of the following were required: name, social security number, date of birth, city, and state. Patients who did not experience any component of the primary outcome were censored at the last study visit. For the extended follow-up analysis, patients who did not appear in the national death index were censored on the day the death index search was completed.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were reported as frequencies. Continuous and categorical variables were compared with Student’s t test and the chi-squared test, respectively. Kaplan- Meier analysis was used to plot the time to first occurrence of the primary outcome, and the 2 groups were compared with the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare chronic and nonchronic NSAID users for risk of the primary and secondary outcomes using stepwise selection of baseline covariates. The percentage of visits with aspirin use also was considered as a covariate. A P value of .2 was used to select covariates to enter the model, while a P value of .05 was used to retain covariates in the model. For each treatment group, the hazard ratios (HR) for the primary outcome were displayed for on-treatment systolic blood pressure in 10 mm Hg increments, using 130 to <140 mm Hg as the referent.

To adjust for the independent contribution of baseline characteristics on the risk of an adverse outcome, chronic NSAID users were compared with a propensity-matched sample (1:1 ratio) of nonchronic NSAID users. A propensity score was calculated using the SAS PROC logistic procedure by determining the probability for each patient to be in one group or another. Then for each chronic NSAID user, a nonchronic NSAID user with approximately the same propensity score (± 0.01) was randomly selected. The 2 propensity- matched groups were then compared using the same Cox regression analysis as described above.

All outcomes were reported from Cox regression analysis unless specifically noted otherwise and were expressed as HR and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Analyses were performed with SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There were 882 chronic NSAID users and 21,694 nonchronic NSAID users (n = 14,408 for never users and n = 7286 for intermittent users). There were significant differences between the chronic and nonchronic groups at baseline. For chronic NSAID versus nonchronic NSAID users, the mean age was 65.3 years versus 66.1 years (P = .02), women were 66.9% versus 51.5% (P < .0001), diabetics were 33.1% versus 28.2% (P = .0014), and a history of peripheral arterial disease was present in 26.5% versus 11.4% (P < .001), respectively. Chronic NSAID users also were less likely to use aspirin and lipid-lowering medications. Detailed baseline characteristics and nonstudy medications are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Medications of the Study Population

| Baseline Characteristic | Chronic NSAIDs (n = 882) |

Nonchronic NSAIDs (n = 21,694) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (SD) | 65.3 (9.9) | 66.1 (9.8) | .02 |

| Age >70 years, % | 29.7 | 33.5 | .02 |

| Women, % | 66.9 | 51.5 | <.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | <.0001 | ||

| White | 11.7 | 49.9 | |

| African American | 10.0 | 13.6 | |

| Hispanic | 75.5 | 34.0 | |

| BMI, mean kg/m2(SD) | 29.5 (5.6) | 29.2 (7.2) | .18 |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | |||

| Systolic, mean (SD) | 147.9 (19.9) | 151.0 (19.5) | <.0001 |

| Diastolic, mean (SD) | 85.0 (10.5) | 87.3 (12.0) | <.0001 |

| History of, % | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 12.9 | 32.8 | <.0001 |

| Stable angina | 90.7 | 65.7 | <.0001 |

| CABG or PCI | 8.7 | 28.1 | <.0001 |

| Stroke or TIA | 5.0 | 7.3 | .009 |

| LVH | 19.2 | 22.0 | .044 |

| Arrhythmia | 3.0 | 7.3 | <.0001 |

| HF (class I to III) | 3.7 | 5.6 | .016 |

| Smoker, current | 12.1 | 12.5 | .78 |

| Smoker, ever | 51.9 | 46.1 | .0006 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33.1 | 28.2 | .0014 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 64.7 | 55.4 | <.0001 |

| Renal insufficiency | 0.68 | 1.9 | .0075 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 26.5 | 11.4 | <.0001 |

| Medications, % | |||

| Aspirin | 46.9 | 57.1 | <.0001 |

| NSAIDs | 100 | 14.4 | <.0001 |

| Diabetes medication | 30.4 | 22.2 | <.0001 |

| Lipid-lowering medication | 32.7 | 36.9 | .01 |

| Nitrates | 71.3 | 34.6 | <.0001 |

| Hormone replacement | 17.2 | 9.2 | <.0001 |

BMI = body mass index; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; HF = heart failure; LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

Mean duration of follow-up for the total patient cohort was 2.7 years (median 2.7 years, 60,970 patient-years), and the mean number of follow-up visits per patient was 8.7 (SD 3.9). Gastrointestinal bleeding occurred in 0% of the chronic NSAID group versus 0.8% of the nonchronic NSAID group. Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures were slightly but statistically lower in the chronic NSAID group throughout follow-up (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure over time by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory group. P < .05 for all time points, except for diastolic blood pressure at 30 months (P = .12) and 36 months (P = .41). NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

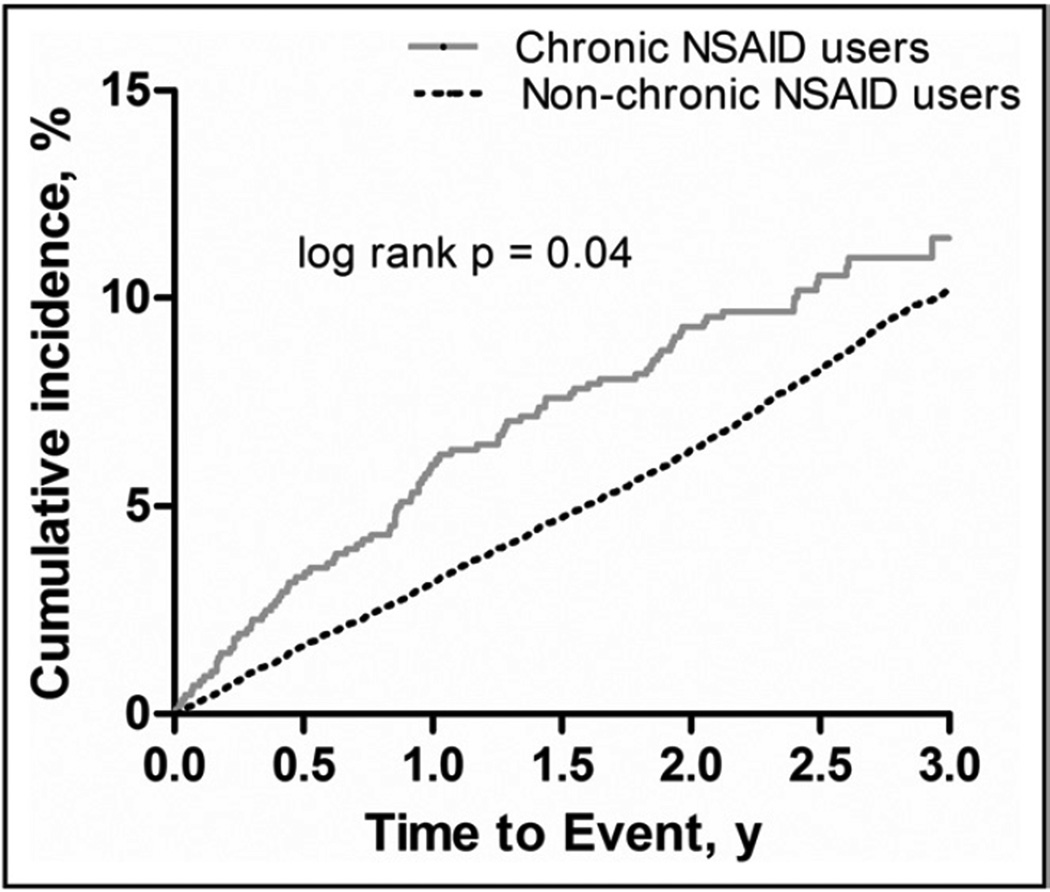

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve for time to the primary outcome by NSAID group. The primary outcome occurred at a rate of 4.4 events per 100 patient-years for chronic NSAID users versus 3.7 events per 100 patient-years for nonchronic NSAID users (adjusted HR 1.47; 95% CI, 1.19–1.82; P = .0003). Independent predictors for the primary outcome are displayed in Table 2. Compared with never users, chronic NSAID users were associated with harm (adjusted HR 1.29; 95% CI, 1.05–1.60; P = .018), while intermittent users were not (adjusted HR 0.73; 95% CI, 0.66–0.80; P < .0001). In the analysis of chronic NSAID users propensity-matched to nonchronic NSAID users, the adjusted HR for the primary outcome was 1.60 (95% CI, 1.18–2.17; P = .0023). Incidence and event rates for additional outcomes are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for the time (years) to first occurrence of the primary outcome by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory group (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.47; 95% confidence interval, 1.19–1.82; P = .0003). NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Table 2.

Independent Predictors of the Primary Outcome

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic NSAID use | 1.47 | 1.19–1.82 | .0003 |

| Percentage of visits with aspirin use | 1.23 | 1.09–1.40 | .0009 |

| Age, per decade | 1.63 | 1.56–1.72 | <.0001 |

| Men | 1.11 | 1.01–1.21 | .028 |

| United States residency | 1.65 | 1.43–1.89 | <.0001 |

| BMI, per 5 kg/m2 | 0.88 | 0.84–0.92 | <.0001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.79 | 0.72–0.86 | <.0001 |

| Diabetes | 1.75 | 1.60–1.91 | <.0001 |

| Current smoking | 1.40 | 1.28–1.54 | <.0001 |

| PAD | 1.25 | 1.12–1.40 | <.0001 |

| Renal insufficiency | 1.49 | 1.22–1.81 | <.0001 |

| Prior: | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 1.36 | 1.24–1.48 | <.0001 |

| CABG or PCI | 1.14 | 1.03–1.25 | .0087 |

| Heart failure | 2.05 | 1.81–2.33 | <.0001 |

| Stroke or TIA | 1.41 | 1.25–1.59 | <.0001 |

| Arrhythmia | 1.16 | 1.02–1.33 | .029 |

| Mean on-treatment SBP* | 1.06 | 1.04–1.08 | <.0001 |

| Mean on-treatment DBP* | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 | .0033 |

BMI = body mass index; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; CI = confidence interval; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; HR = hazard ratio; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PAD = peripheral arterial disease; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; SBP = systolic blood pressure; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

per 5 mm Hg.

Table 3.

Event Rates for Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes

| Variable | Chronic NSAIDs (Events per 100 Pt-yrs) |

Nonchronic NSAIDs (Events per 100 Pt-yrs) |

Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death, MI, stroke | 4.4 | 3.7 | 1.47 (1.19–1.82) | .0003 |

| All-cause mortality | 4.3 | 2.8 | 1.89 (1.53–2.35) | <.0001 |

| All-cause mortality (extended follow-up)* | 3.1 | 2.4 | 1.24 (1.05–1.47) | .013 |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 2.4 | 1.4 | 2.26 (1.70–3.01) | <.0001 |

| Fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.66 (1.21–2.28) | .0017 |

| Fatal and nonfatal stroke | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.85 (0.43–1.65) | .63 |

CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; MI = myocardial infarction; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; Pt-yrs = patient-years.

US cohort of patients.

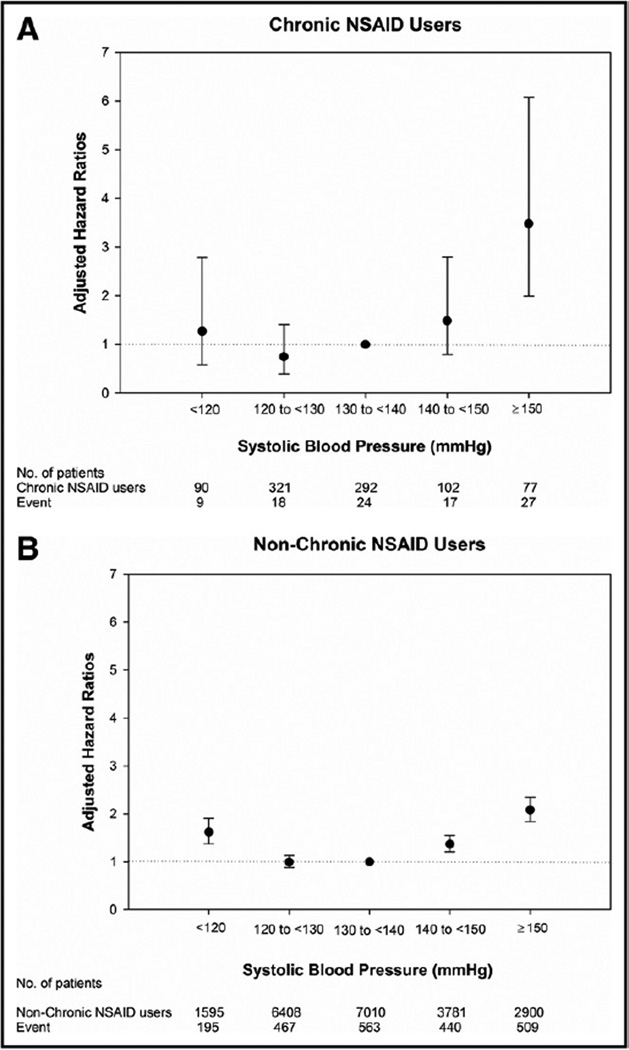

Blood pressure modified the relationship between chronic NSAID exposure and adverse outcomes (P for interaction <.0001). The adjusted HR for the primary outcome and mean systolic blood pressure (in increments of 10 mm Hg) was displayed for the 2 groups in Figure 3. For chronic NSAID users, the risk of the primary outcome was markedly increased for mean systolic blood pressure >150 mm Hg (although with wide confidence intervals) compared with patients with a mean systolic blood pressure of 130–140 mm Hg.

Figure 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios for the primary outcome in the 2 treatment groups as a function of mean systolic blood pressure. NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

As an added note, during the extended follow-up of the US cohort, there were 833 chronic NSAID users and 16,298 nonchronic NSAID users. Over a mean duration of follow-up of 7.6 years (median 8.4 years, 130,772 patient-years), all-cause mortality was significantly increased from earlier self-reported chronic NSAID use (adjusted HR = 1.24; 95% CI, 1.05–1.47; P = .013).

DISCUSSION

Among hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease, chronic self-reported NSAID use over a mean of 2.7 years was associated with a 47% increase in the first occurrence of death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke. This was due to a 90% increase in all-cause mortality (which persisted into extended follow-up of more than 5 years), a 126% increase in cardiovascular mortality, and a 66% increase in total myocardial infarctions. There was no significant difference in total stroke.

Because we did not have information on NSAID type or dose, our findings should be considered a class effect. It is unknown if a particular agent was responsible for the excess risk. The ongoing Prospective Randomized Evaluation of Celecoxib Integrated Safety versus Ibuprofen Or Naproxen (PRECISION) trial should help to determine the relative safety of these 3 particular NSAIDs.20 Placebo-controlled trials also are needed to determine the overall safety of NSAIDs. Until randomized trial data are reported, clinical judgment should be exercised in caring for at-risk individuals.

It is noteworthy that the average age of our study participants was 65 years and approximately one third were older than 70 years. Study participants also had clinically stable coronary artery disease, including remote myocardial infarction in one third. Approximately 50% of participants were chronically taking aspirin throughout the study. A recent American Geriatrics Society Panel on the treatment of chronic pain in the elderly recommended acetaminophen as the first-line agent.21 The panel suggested that nonselective NSAIDs or cyclooxygenase-2-specific agents only be used with extreme caution. Our findings support this recommendation.

Chronic NSAID users had a lower mean systolic blood pressure at baseline and throughout the follow-up period. The current opinion is that NSAIDs increase blood pressure, but this has not been established with long-term use from studies that focus on blood pressure and blood pressure control. In one meta-analysis, short-term use of NSAIDs was associated with a 5 mm Hg increase in systolic blood pressure;22 however, a more recent meta-analysis of short-term use of NSAIDs documented a significant blood pressure-raising effect only for ibuprofen.23 Despite lower mean systolic blood pressure and other characteristics that would have been expected to decrease the risk for adverse events (for example, younger age and less frequent history of myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure), the net effect from multivariate modeling and propensity matching was an increase in long-term adverse cardiovascular events.

The Physicians’ Health Study enrolled male patients without preexisting cardiovascular disease and found that aspirin was effective at preventing first myocardial infarction except among those who reported taking NSAIDs at least 60 days per year, where the risk of myocardial infarction was increased.24 The mechanism for the harmful effect of NSAIDs could be that these agents interfere with the irreversible inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase-1 enzyme by aspirin because they compete for binding at the same site.25,26 This effect might be minimized by taking a nonselective NSAID at least 30 to 60 minutes after aspirin, or taking aspirin at least 8 hours after a short-acting nonselective NSAID.

The relationship between the primary outcome and mean systolic blood pressure between the study groups was similar except for very high systolic blood pressures. Chronic NSAID users appeared to be disproportionately harmed by markedly elevated blood pressure (systolic blood pressure >150 mm Hg); however, the level of uncertainty was high at this blood pressure level due to relatively few events.

Strengths

This observational study was conducted within a large randomized trial that provided long-term blood pressure measures, target blood pressures, and standardized assessment of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Many of the previous analyses on this topic have been conducted from case- control studies. We did not find a difference in serious gastrointestinal bleeding events from chronic NSAID use, as might have been expected.27,28 While this was somewhat counterintuitive, chronic NSAID users likely started these medications before study enrollment, at which time major bleeding events could have occurred. Therefore, patients who remained on these medications into study enrollment had essentially demonstrated that they were able to tolerate them without adverse events. It also is possible that because bleeding was not a primary focus of this trial, some events might have been missed.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. As previously pointed out, we did not have information on the specific type of NSAIDs or doses that patients were taking. The Nurses’ Health Study was conducted during a similar time period and found that naproxen or ibuprofen was used in the majority of patients; therefore, one might expect a similar proportionate use of these medications in the present study.29 In a very limited sample of patients in the current study, the most commonly used NSAIDs were naproxen and ibuprofen. Diclofenac and celecoxib were reported in a small proportion of patients.

Long-term NSAID use might be a marker for chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, which has been shown to independently predict adverse outcomes.30 A more frequent indication for chronic NSAID use is osteoarthritis, which also is associated with an increased prevalence of most of the cardiovascular risk factors, including metabolic syndrome.31–33 We did not have baseline information on rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. In addition, other unknown patient characteristics make confounding by indication a possibility. A separate study documented a harmful association between NSAIDs and adverse events after controlling for rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis.29

The Kaplan-Meier curves appeared to converge late in follow-up. This was likely due to a variety of reasons. Events in chronic NSAID users occurred more rapidly than nonchronic NSAID users. Due to the smaller sample size of the chronic NSAID users, the Kaplan-Meier curve for that group becomes unstable late in follow-up. Given a long enough study time, all Kaplan-Meier curves will eventually converge when all patients have either experienced the event or become censored. In multivariate modeling, obesity and hypercholesterolemia appeared to have protective effects from adverse events. These paradoxes have been previously described and they deserve further study.34,35 Lastly, we considered the use of NSAIDs at each follow-up visit as a proxy for daily use. It is possible that some of the patients categorized as chronic NSAID users were not daily users; however, this potential miscategorization would have posed more of a problem if no association was found with chronic NSAID use.

CONCLUSIONS

Among coronary artery disease patients with hypertension, chronic self-reported use of NSAIDs was associated with harmful outcomes, and this practice should be avoided where possible. This association did not appear to be due to elevated blood pressure because chronic NSAID users actually had slightly lower on-treatment blood pressure over a mean of 2.7 years of follow-up. Until further data are available, alternative modes of pain relief should be considered for these patients.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE.

Chronic pain syndromes are commonly treated with long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Many of these patients have underlying hypertension and coronary artery disease.

Currently, there is a paucity of data about possible harmful effects of chronic NSAIDs in patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding: INVEST was funded by a grant from Abbott Laboratories and the University of Florida Opportunity Fund.

Dr. Handberg received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [NHLBI]), Abbott Laboratories, Fujisawa, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Cooper-DeHoff received research funding from Abbott Laboratories during the conduct of INVEST and is currently receiving funding from NIH (NHLBI) K23HL086558. Dr. Pepine received research grants from NIH (NHLBI), Baxter, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bioheart, Inc. and is a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Forest Laboratories, Novartis/Cleveland Clinic, NicOx, Angioblast, Sanofi-Aventis, NHLBI, NIH, Medtelligence, and SLACK Inc. Drs. Handberg and Pepine have received educational grants from the Vascular Biology Working Group (AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, Daiichi-Sankyo Lilly, AtCor Medical, and XOMA).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Drs. Bavry, Khaliq, and Gong have no financial disclosures.

Authorship: This work is original, and all authors significantly contributed to this paper and accept responsibility for its scientific content.

References

- 1.Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1520–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1092–1102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, et al. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1071–1080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juni P, Nartey L, Reichenbach S, Sterchi R, Dieppe PA, Egger M. Risk of cardiovascular events and rofecoxib: cumulative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2004;364:2021–2029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17514-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon SD, Wittes J, Finn PV, et al. Cardiovascular risk of celecoxib in 6 randomized placebo-controlled trials: the cross trial safety analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:2104–2113. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.764530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J, Halls H, Emberson JR, Patrono C. Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2006;332:1302–1308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antman EM, Bennett JS, Daugherty A, Furberg C, Roberts H, Taubert KA. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;115:1634–1642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.181424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waksman JC, Brody A, Phillips SD. Nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiovascular risk: are they safe? Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1163–1173. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham DJ, Campen D, Hui R, et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death in patients treated with cyclooxygenase 2 selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: nested case-control study. Lancet. 2005;365:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17864-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients taking cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: population based nested case-control analysis. BMJ. 2005;330:1366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7504.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fosbol EL, Folke F, Jacobsen S, et al. Cause-specific cardiovascular risk associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs among healthy individuals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:395–405. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.861104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk and inhibition of cyclooxygenase: a systematic review of the observational studies of selective and nonselective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase 2. JAMA. 2006;296:1633–1644. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.13.jrv60011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:c7086. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin BK, Szekely C, Brandt J, et al. Cognitive function over time in the Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT): results of a randomized, controlled trial of naproxen and celecoxib. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:896–905. doi: 10.1001/archneur.2008.65.7.nct70006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gislason GH, Jacobsen S, Rasmussen JN, et al. Risk of death or reinfarction associated with the use of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006;113:2906–2913. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.616219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald TM, Wei L. Effect of ibuprofen on cardioprotective effect of aspirin. Lancet. 2003;361:573–574. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curtis JP, Wang Y, Portnay EL, Masoudi FA, Havranek EP, Krumholz HM. Aspirin, ibuprofen, and mortality after myocardial infarction: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2003;327:1322–1323. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7427.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Cooper-DeHoff RM, et al. A calcium antagonist vs a non-calcium antagonist hypertension treatment strategy for patients with coronary artery disease. The International Verapamil-Trandolapril Study (INVEST): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2805–2816. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.21.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker MC, Wang TH, Wisniewski L, et al. Rationale, design, and governance of Prospective Randomized Evaluation of Celecoxib Integrated Safety versus Ibuprofen Or Naproxen (PRECISION), a cardiovascular end point trial of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents in patients with arthritis. Am Heart J. 2009;157:606–612. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Geriatrics Society Panel on Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1331–1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson AG, Nguyen TV, Day RO. Do nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs affect blood pressure? A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:289–300. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-4-199408150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison A, Ramey DR, van Adelsberg J, Watson DJ. Systematic review of trials of the effect of continued use of oral non-selective NSAIDs on blood pressure and hypertension. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2395–2404. doi: 10.1185/030079907X219553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurth T, Glynn RJ, Walker AM, et al. Inhibition of clinical benefits of aspirin on first myocardial infarction by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Circulation. 2003;108:1191–1195. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000087593.07533.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catella-Lawson F, Reilly MP, Kapoor SC, et al. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors and the antiplatelet effects of aspirin. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1809–1817. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Capone ML, Sciulli MG, Tacconelli S, et al. Pharmacodynamic interaction of naproxen with low-dose aspirin in healthy subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1295–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1888–1899. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906173402407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjorkman DJ, Kimmey MB. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gastrointestinal disease: pathophysiology, treatment and prevention. Dig Dis. 1995;13:119–129. doi: 10.1159/000171493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan AT, Manson JE, Albert CM, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and the risk of cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2006;113:1578–1587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodson N. Coronary artery disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14:115–120. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh G, Miller JD, Lee FH, Pettitt D, Russell MW. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among US adults with self-reported osteoarthritis: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:S383–S391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puenpatom RA, Victor TW. Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in individuals with osteoarthritis: an analysis of NHANES III data. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:9–20. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.11.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Velasquez MT, Katz JD. Osteoarthritis: another component of metabolic syndrome? Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2010;8:295–305. doi: 10.1089/met.2009.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uretsky S, Messerli FH, Bangalore S, et al. Obesity paradox in patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 2007;120:863–870. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang TY, Newby LK, Chen AY, et al. Hypercholesterolemia paradox in relation to mortality in acute coronary syndrome. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:E22–E28. doi: 10.1002/clc.20518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]