Abstract

Two major factors which regulate tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF)-mediated constriction of the afferent arteriole are release of superoxide (O2−) and nitric oxide (NO) by macula densa (MD) cells. MD O2− inactivates NO; however, among the factors that increase MD O2− release, the role of aldosterone is unclear. We hypothesize that aldosterone activates the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) on MD cells, resulting in increased O2− production due to upregulation of cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-2) and NOX-2, and NOX-4, isoforms of NAD(P)H oxidase. Studies were performed on MMDD1 cells, a renal epithelial cell line with properties of MD cells. RT-PCR and Western blotting confirmed the expression of MR. Aldosterone (10−8 mol/l for 30 min) doubled MMDD1 cell O2− production, and this was completely blocked by MR inhibition with 10−5 mol/l eplerenone. RT-PCR, real-time PCR, and Western blotting demonstrated aldosterone-induced increases in COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 expression. Inhibition of COX-2 (NS398), NADPH oxidase (apocynin), or a combination blocked aldosterone-induced O2− production to the same degree. These data suggest that aldosterone-stimulated MD O2− production is mediated by COX-2 and NADPH oxidase. Next, COX-2 small-interfering RNA (siRNA) specifically decreased COX-2 mRNA without affecting NOX-2 or NOX-4 mRNAs. In the presence of the COX-2 siRNA, the aldosterone-induced increases in COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 mRNAs and O2− production were completely blocked, suggesting that COX-2 causes increased expression of NOX-2 and NOX-4. In conclusion 1) MD cells express MR; 2) aldosterone increases O2− production by activating MR; and 3) aldosterone stimulates COX-2, which further activates NOX-2 and NOX-4 and generates O2−. The resulting balance between O2− and NO in the MD is important in modulating TGF.

Keywords: tubuloglomerular feedback, renal hemodynamics, nitric oxide, kidney

in patients with myocardial infarction or heart failure, aldosterone has been shown to promote cardiac inflammation. This is accompanied by increases in myocardial oxidative stress and release of inflammatory markers that include cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (35). Aldosterone also causes nitric oxide (NO)-mediated vasodilation and superoxide (O2−) release due to activation of NADPH oxidase (18) in cerebral and mesenteric arterioles. In cultured aortic endothelial cells, aldosterone has also been shown to induce O2− generation by activating NADPH oxidase (9).

Tubuloglomerular glomerular feedback (TGF) is a critical mechanism for regulation of renal hemodynamics, NaCl excretion, and blood pressure (4, 39, 43). Increasing tubular flow to the macula densa (MD) initiates a TGF signal causing constriction of the afferent arteriole, thus decreasing GFR. NO released from the MD modulates the TGF response, and O2− release from the MD will inactivate NO (10, 24, 25, 28). Recently, we found that NOX-2 and NOX-4 isoforms of NAD(P)H oxidase are expressed in the rat MD and MMDD1 cells (46). Although the role of aldosterone as a prooxidant and a proinflammatory agent has been established in the heart and in blood vessels, the prooxidant role of aldosterone in the MD is poorly understood. In addition, aldosterone activates mineralocorticoid receptors (MR), which have been found throughout the body but of particular interest to this paper, in the distal tubules, connecting tubules, and collecting ducts of the kidney (13, 29). The presence of MR in the MD cells has not been reported. Our hypothesis is that aldosterone increases O2− production from MD cells acting through MR, and this is accompanied by increases in COX-2 production and NADPH oxidase via NOX-2 and NOX-4 production. These studies will greatly enhance our understanding of the role of aldosterone in regulating TGF and renal hemodynamics.

METHODS

All experiments were approved by the University of Mississippi Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee before any procedures were performed. All reagents for cell culture were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), except DMSO and lucigenin, which were obtained from Invitrogen.

MMDD1 cells.

We used MMDD1 cells, a renal epithelial cell line with properties of MD cells, developed and kindly supplied by Dr. J. Schnermann (National Institutes of Health). These cells were derived from SV40 transgenic mice and have been shown to express well-known MD markers, e.g., COX-2, neuronal NO synthase (nNOS), ROMK, and the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (44). In the present study, MMDD1 cells at passages 21–27 were routinely trypsinized and suspended in DMEM nutrient mixture-Ham's F-12, supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The cells were plated onto culture dishes and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% room air-5% CO2. The medium was changed every 2 days, and once the cells reached confluence (typically in 2–3 days), the cells were ready for small-interfering RNA (siRNA) and O2− experiments.

Measurement of O2− with lucigenin.

We measured O2− production in the MMDD1 cells using a lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence assay, as described previously (10). Briefly, MMDD1 cells (10-cm dish) were washed by PBS two times, trypsinized from the dish, and kept in 12 ml Krebs/HEPES buffer [containing (in mmol/l) 115 NaCl, 20 HEPES, 1.17 K2HPO4, 1.17 MgSO4, 4.3 KCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 11.7 glucose, and 0.1 NAD(P)H, pH adjusted to 7.4]. The Krebs/HEPES buffer was evenly divided among the following five groups with different antagonists: control; aldosterone (10−8 mol/l); aldosterone (10−8 mol/l) and NS398 (10−6 mol/l); aldosterone (10−8 mol/l) and apocynin (10−5 mol/l); and aldosterone (10−8 mol/l), NS398 (10−6 mol/l), and apocynin (10−5 mol/l). Then, lucigenin (5 × 10−6 mol/l) was added to each of the samples, which were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with bubbling oxygen. From each group, a 0.5-ml sample was transferred into 1.6-ml polypropylene 8 × 50-mm tubes (Evergreen Scientific), and then using a Sirius luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany), O2− was measured following the manufacturer's instructions. Luminescence was measured for 10 s with a delay of 5 s.

RT-PCR for MMDD1 cells.

Total RNA from the MMDD1 cells and mouse heart cells (as a positive control for the MR receptor) was extracted with an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed for 1 h at 42°C using 1 μl random primer (3 μg/μl, Invitrogen) and an Ambion RETROscript kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer's instructions. In the protocol of RT-PCR for COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4, measured by specific subunit for each NOX isoform, the resultant RT product was then amplified by PCR by adding 1 μl of the RT reaction, 1 μmol/l of the gene-specific primers (Invitrogen), 2 μl 10× complete PCR buffer (Ambion), 1 μl dNTP mix (Ambion), 2.5 mmol/l each, 0.2 μl Super Taq, 5 U/μl (Ambion), (1.2 μl glycerol, 50% only for NOX-2 and NOX-4), and adding nuclear-free water (Invitrogen) to achieve a volume of 20 μl. The mixed samples were heated to 94°C for 3 min and cycled at 94°C for 20 s, 59.4°C (COX-2), 56.6°C (NOX-2), 52.9°C (NOX-4) for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s for 40 cycles. Final extension was for 8 min at 72°C. In the protocol for RT-PCR for the MR receptor, the mixed samples (50 μl containing 1 μl cDNA or 1 μl mouse heart cDNA) using the described primers and using Titanium Taq polymerase were heated to 95°C for 2 min and cycled at 95°C for 40 s, annealing temperature 58°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 55 s for 40 cycles. Final extension was for 8 min at 72°C. The amplified products of RT-PCR were run on 1.4% (0.5% for MR receptor) agarose gels containing ethidium bromide (10 mg/ml, Invitrogen) and visualized under UV light. β-Actin, as a housekeeping gene, was set up as an internal loading control. A 100-bp DNA ladder marker was used to identify the molecular weight of the targeted DNA. Primer sequences and expected bands are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences and expected band

| Gene | Primer Sequences | PCR Length, bp |

|---|---|---|

| COX-2 | F: 5′-cacagcctaccaaaacagcca-3′ | 99 |

| R: 5′-gctcagttgaacgccttttga-3′ | ||

| NOX-2 | F: 5′-ccagtgaagatgtgttcagct-3′ | 155 |

| R: 5′-gcacagccagtagaagtagat-3′ | ||

| NOX-4 | F: 5′-accagatgttgggcctaggattgt-3′ | 261 |

| R: 5′-agttcactgagaagttcagggcgt-3′ | ||

| β-Actin | F: 5′-aaccctaaggccaaccgtgaaaag-3′ | 241 |

| R: 5′-tcatgaggtagtctgtcaggt-3′ | ||

| MR | F: 5′-cacggctcttttgaagaagact-3′ | 90 |

| R: 5′-atctgtttggtgtgtggagatg-3′ |

F, forward; R, reverse; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; NOX-2 and NOX-4, isoforms of NAD(P)H oxidase; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor.

Real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR was used to quantify the mRNA level of the COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 responses to aldosterone. Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen), and complementary DNA synthesis was carried out as described in the method for RT-PCR. Real-time PCR was performed in a C1000TM Thermal Cycler real-time PCR machine (Bio-Rad). β-Actin was used as a housekeeping gene.

Preparations for siRNA.

COX-2 siRNA was used a predesigned product (Ambion). siRNA transfection was performed using a siPORTTM Amine Transfection Agent (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Scrambled siRNAs were synthesized and used as negative controls (Invitrogen). At 24 h before transfection, MMDD1 cells were transferred onto six-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well) with antibiotic-free medium. The cells were transfected with 10 nmol/l COX-2 siRNA duplex using an Amine Transfection Agent for 18 h in medium devoid of antibiotics. This procedure does not affect cell viability, measured with calcein as we described previously (26, 27). The MMDD1 cells were washed once with PBS and grown in complete medium. Gene silencing was monitored by measuring RNA after incubation for 24 h. We added aldosterone (10−8 mol/l) into each cell culture well and incubated it at 37°C for 30 min in a cell incubator before harvesting the MMDD1 cells.

Western blotting for MMDD1 cells.

MMDD1 cell proteins were extracted with RIPA buffer plus a protease inhibitor cocktail. Protein concentration was measured using a Nanodrop instrument (Thermo Scientific). Cells were homogenized in RIPA buffer, centrifuged, and protein was measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer measuring absorption at 280 nm. Proteins extracted from MMDD1 cells in the amount of 100, 50, and 20 μg were separated by 8% PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, respectively. After the transfer, membranes were blocked at room temperature for 1 h with 1% fat-free dry milk in TTBS (10 mmol/l Tris·HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/l NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20). The membranes were blocked and probed with the following primary antibodies, respectively: 1) MR, mixture of rMR 1–18 clone 1D5 (1:50 dilution) and MRN 365 clone 2D6 (1:100 dilution, overnight incubation); 2) COX-2 antibody (1:500 dilution, ab52237, Abcam); NOX-2 antibody (1:1,000 dilution, ab80508, Abcam); 3) NOX-4 antibody (horseradish peroxidase, 1:1,000 dilution, ab81967, Abcam); and 4) GAPDH (1:5,000, G8795, 4°C, overnight incubation, Sigma); this was followed by the secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase goat anti-mouse IgG1, 10,000 dilution, 1-h incubation, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). The bands were visualized using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and captured with a VersaDoc image analysis system (Bio-Rad).

Statistics.

Data were analyzed as repeated measures over time or compared with a common control. We tested only the effects of interest, using ANOVA for repeated measures and a post hoc Fisher least significant difference test. The changes were considered to be significant if P < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

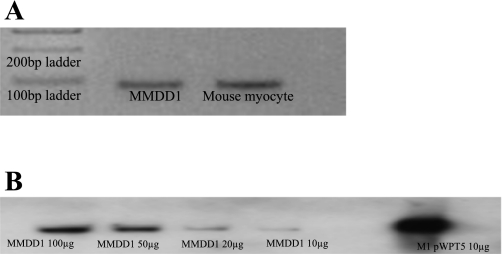

Mineralocorticoid receptors exist on MMDD1 cells.

Figure 1A shows the RT-PCR results for the MR on MMDD1 cells. We used mouse myocardial cells as a positive control. Figure 1B shows the Western blot results of MR protein compared with the positive control. The results for the first time demonstrate the existence of mRNA and protein for MR in MMDD1 cells.

Fig. 1.

Expression of mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) in MMDD1 cells. A: RT-PCR shows that the MMDD1 cells express the mRNA for the MR. Mouse myocytes were used as a positive control. B: Western blotting demonstrates the MR protein in MMDD1 cells.

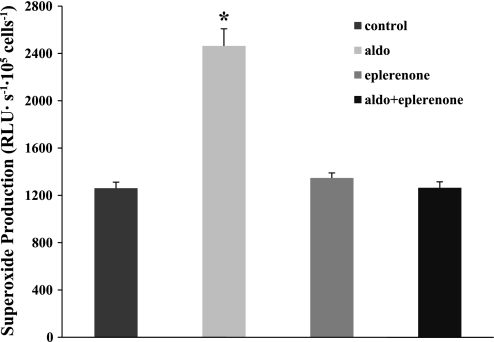

Aldosterone acts through the MR to produce superoxide.

We measured O2− levels in aldosterone-treated MMDD1 cells with and without the MR receptor inhibitor (eplerenone, 10−5 mol/l) to confirm that the effect of aldosterone is mediated by the MR. As shown in Fig. 2, eplerenone completely prevented aldosterone-induced increases in O2− in the MMDD1 cells. O2− levels were 1,260.9 ± 50.9 RLU·s−1·105 cells−1 in untreated MMDD1 cells. It increased to 2,463.5 ± 145.2 RLU·s−1·105 cells−1 after treatment with aldosterone (10−8 mol/l) for 30 min. In the presence of the MR antagonist eplerenone (10−5 mol/l), aldosterone-induced O2− production was blocked (1,264.4 ± 50.0 RLU·s−1·105 cells−1). Eplerenone itself had no significant effect on O2− levels in MMDD1 cells (1,347.0 ± 42.9 RLU·s−1·105 cells−1).

Fig. 2.

Aldosterone (aldo) stimulates superoxide production via MR in MMDD1 cells. Aldosterone stimulates O2− significantly (n = 45, where n is the number of independent samples). Blocking MR with eplerenone (n = 45) blocked aldosterone-induced increased in O2−. Eplerenone (n = 48) had no effect on O2− in the absence of aldosterone compared with control group (n = 44). *P < 0.05 vs. untreated cells, which were used as a control.

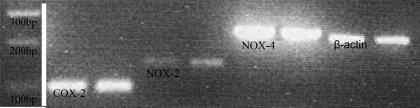

COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 are expressed in MMDD1 cells.

Because the MMDD1 cell line may have some subtle differences from MD cells isolated in vivo (15), we made sure the MMDD1 cells expressed COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4. The representative blot depicted in Fig. 3 shows that COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 are expressed in the MMDD1 cells, and this result also verifies the efficacy of all of our primers to detect COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4.

Fig. 3.

mRNAs of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and NOX-2 and NOX-4, isoforms of NAD(P)H oxidase, are detected in MMDD1 cells. RT-PCR shows that COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 are expressed in MMDD1 cells. The ladder was cut from the same gel film.

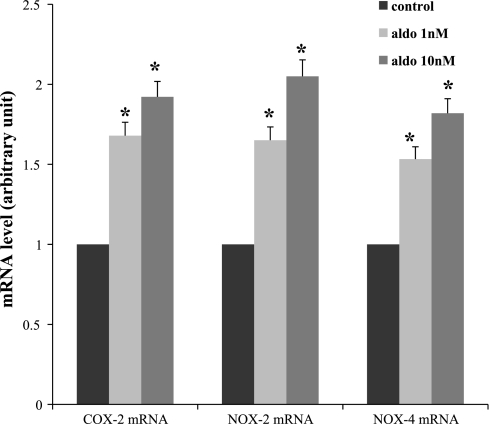

Aldosterone enhances COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 mRNA and protein expression.

We used different aldosterone concentrations (1 and 10 nmol/l) to stimulate the MMDD1 cells for 30 min. The results in Fig. 4 show that exposing MMDD1 cells to aldosterone at different concentrations enhances COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4. Aldosterone at 10−8 mol/l had the greatest effect (1.84-, 1.95-, and 1.82-fold increases in COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 mRNA expression, respectively). Therefore, we used this concentration of aldosterone in the following experiment.

Fig. 4.

Dose-response of aldosterone in mRNAs of COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4. Aldosterone at 10−9 and 10−8 mol/l for 30 min enhances mRNAs of COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4, and aldosterone at 10−8 mol/l had the greater effect; n = 3 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. control.

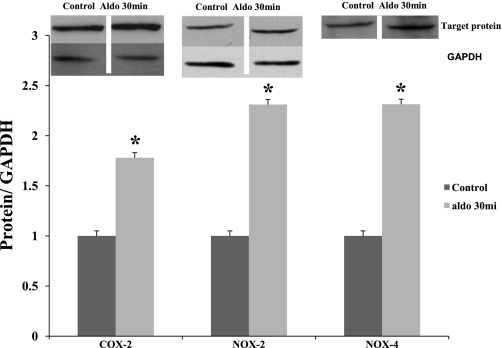

We measured protein levels of COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX4 with specific antibodies in MMDD1 cells stimulated with aldosterone (10−8 mol/l) for 30 min. The results in Fig. 5 show that aldosterone significantly increased protein levels of COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 by 1.78-, 2.31-, and 2.33-fold.

Fig. 5.

Aldosterone enhances protein levels of COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 as measured by Western blotting. Aldosterone at 10−8 mol/l for 30 min increases protein levels of COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 in MMDD1 cells. The amount of protein for the band was 40 ng. The bands were cut from the same gel films. GAPDH was used as a control for both NOX-2 and NOX-4.

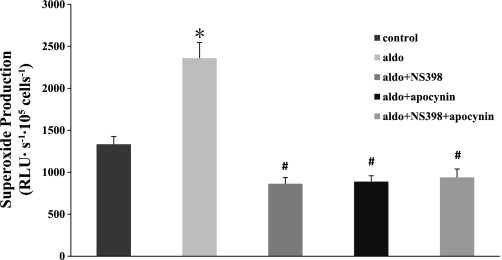

COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 are a major source of aldosterone-induced O2−.

We next identified the major sources of aldosterone-induced O2− in MMDD1 cells. For this, we measured O2− levels in aldosterone-treated cells (10−8 mol/l) in the presence of NS-398 (10−6 mol/l, inhibits COX-2), apocynin (10−5 mol/, inhibits NOX), or in the presence of both NS-398 (10−6 mol/l) and apocynin (10−5 mol/l). As shown in Fig. 6, apocynin, NS398, or both NS398 and apocynin completely prevented aldosterone-induced increases in O2− in MMDD1 cells. O2− levels were 1,333.8 ± 92.8 RLU·s−1·105 cells−1 in untreated MMDD1 cells. It increased to 2,359.1 ± 187.5 RLU·s−1·105 cells−1 after treatment with aldosterone. In the presence of either NS-398 or apocynin, aldosterone-induced increases in O2− were blocked (863.3 ± 74.7 RLU·s−1·105 cells−1, 939.3 ± 100.5 RLU·s−1·105 cells−1, respectively). These data suggested that COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 were the primary sources of O2− produced by the MMDD1 cells during aldosterone stimulation.

Fig. 6.

Aldosterone-induced O2− production is blocked by COX-2 or NAD(P)H oxidase inhibition. Aldosterone (10−8 mol/l) stimulated O2− significantly in MMDDl cells (n = 61) compared with untreated control cells (n = 58). Blocking COX-2 with NS-398 (n = 60), NAD(P)H oxidase with apocynin (n = 61), or both COX-2 and NAD(P)H oxidase (n = 48) blocked aldosterone-induced O2−. *P < 0.05 vs. control. #P < 0.05 vs. aldosterone group.

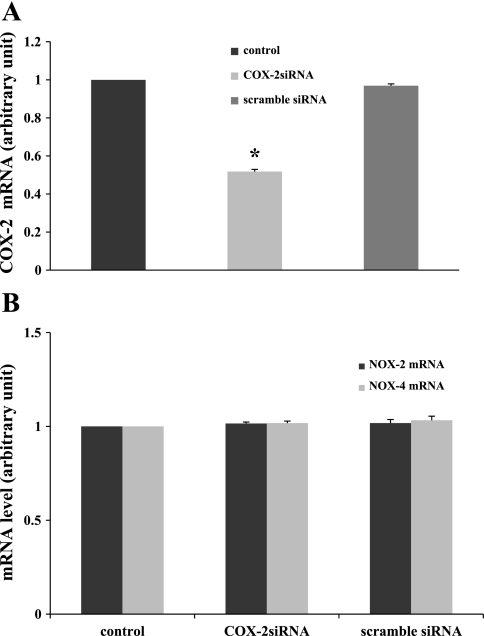

An siRNA knocked down COX-2 in MMDD1 cells.

To study the function of COX-2 in aldosterone-induced O2− generation, we used an siRNA to silence COX-2. As shown in Fig. 7A, COX-2 siRNA significantly reduced its target COX-2 mRNA (51.8 ± 1.2% vs. control). Scrambled siRNA had no significant effect on COX-2 mRNA (96.9 ± 0.9% vs. control). Therefore, the results show that the COX-2 siRNA effectively knocked down COX-2 mRNA. Next, we determined whether this siRNA had any effect on NOX-2 or NOX-4 mRNA levels. Figure 7B shows that COX-2 siRNA did not affect NOX-2 mRNA expression (101.5 ± 0.8% vs. control) or NOX-4 mRNA expression (101.8 ± 1.0% vs. control). Scrambled siRNA had no effect on NOX-2 mRNA expression (101.6 ± 1.4% vs. control) or NOX-4 mRNA expression (106.1 ± 5.0% vs. control). These data demonstrate the efficiency and specificity of COX-2 siRNA.

Fig. 7.

Efficiency and specificity of COX-2 siRNA. A: effects of COX-2 small-interfering RNA (siRNA) or scrambled siRNA on COX-2 mRNA. COX-2 siRNA reduces COX-2 mRNA level significantly (n = 17) compared with the untreated control cells (n = 21). Scrambled siRNA (n = 6) had no effect on COX-2 mRNA level. B: knocking down COX-2 mRNA with COX-2 siRNA did not affect the NOX-2 and NOX-4 mRNAs (no. of experiments for each group: control = 9, NOX-2 = 9, NOX-4 = 12; COX-2 siRNA = 12, NOX-2 = 12, NOX-4 = 12). Scrambled siRNA (NOX-2 = 6, NOX-4 = 5) had no effect. *P < 0.05 vs. control.

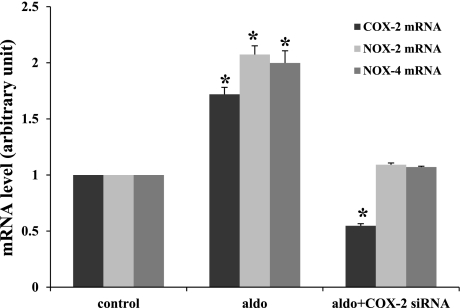

COX-2 siRNA blocked the effect of aldosterone on COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 mRNAs and O2− generation.

To study the role and their interactions between COX-2 and NOX-2 or NOX-4 in aldosterone-induced increases, we knocked down COX-2 and measured NOX-2 and NOX-4 levels. As shown in Fig. 8, aldosterone (10−8 mol/l) stimulated COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 mRNA expression levels to 171.9 ± 6.2, 207.4 ± 7.8, and 199.8 ± 10.9%, respectively. In the MMDD1 cells treated with COX-2 siRNA, aldosterone-induced increases in NOX-2 and NOX-4 mRNAs were blocked (109.1 ± 1.6 and 107.1 ± 0.8%, respectively), and COX-2 mRNA was reduced by 54.7 ± 1.9%.

Fig. 8.

COX-2 siRNA blocked aldosterone-induced increases in mRNAs of COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4. Aldosterone stimulated COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 mRNA levels significantly (control = 7, COX-2 = 7, NOX-2 = 5, NOX-4 = 6; aldo+COX-2 = 5, aldo+NOX-2 = 5, aldo+NOX-4 = 4). Knocking down the COX-2 mRNA with COX-2 siRNA (COX-2 = 8, NOX-2 = 7, NOX-4 = 7) blocked the effect of aldosterone on COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 mRNAs. *P < 0.05 vs. control.

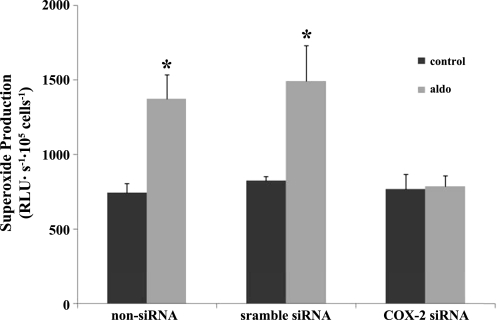

To study the role of COX-2 in aldosterone-induced O2− generation, we knocked down COX-2 and measured O2−. As shown in Fig. 9, aldosterone (10−8 mol/l) enhanced O2− from 748.2 ± 58.4 to 1,372.1 ± 164.7 RLU·s−1·105 cells−1 In the MMDD1 cells treated with COX-2 siRNA, aldosterone-induced increases in O2− generation were blocked (772.2 ± 97.0, 788.3 ± 72.3 RLU·s−1·105 cells−1).

Fig. 9.

COX-2 siRNA blocked aldosterone-induced increases in O2−. Knocking down COX-2 mRNA with COX-2 siRNA blocked the effect of aldosterone on O2−; n = 3. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated control cells.

These data indicate a novel signaling pathway for aldosterone-induced O2− generation in MD cells. Aldosterone stimulates COX-2, which further activates NOX-2 and NOX-4 and generates O2−.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the MR was expressed on MMDD1 cells. Aldosterone stimulates O2− production in MMDD1 cells mediated by MR. Both mRNA and protein levels of COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 were upregulated by aldosterone. Knocking down COX-2 with an siRNA blocked aldosterone-induced increases in NOX-2 and NOX-4 as well as O2− production. Our data indicate that aldosterone stimulates COX-2, which further activates NOX-2 and NOX-4, resulting in enhanced O2− production.

We report for the first time an MR on MMDD1 cells as confirmed by RT-PCR and Western blotting, and these cells demonstrated an elevation in O2− production when exposed to aldosterone. Blocking the MR with eplerenone completely blocked the prooxidant effect of aldosterone. This suggests that aldosterone-induced O2− release from MMDD1 cells is mediated by the MR. PCR analysis clearly showed that COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 were present in MMDD1 cells. COX-2 is profoundly expressed in the MD and is important in modulating TGF and renal hemodynamics (1, 6, 34, 42). NOX-2 and NOX-4 are isoforms of NAD(P)H oxidase expressed in the MD (46), which are important for salt and ANG II-induced O2− production (10, 46). However, the interaction between COX-2 and NOXs are not clear. We found that COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 mRNAs and protein levels increased in MMDD1 cells exposed to aldosterone for 30 min. As shown in Fig. 6, this prooxidant effect of aldosterone was eliminated with NS398, a blocker of COX-2; apocynin, a blocker of NADPH oxidase; and with a combination of NS398 and apocynin. These data indicate that COX-2 and NAD(P)H oxidase are the primary sources for aldosterone-induced O2− production in the MD. Similar O2− production was found in the presence of aldosterone combined with NS398, apocynin, or NS398+apocynin, suggesting a series effect of COX-2 and NAD(P)H oxidase.

Other new data in this study include a strong effect of COX-2 siRNA in inhibiting the aldosterone-induced increases in COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 mRNAs in MMDD1 cells. A specific COX-2 siRNA effectively and selectively knocked down COX-2 mRNA in MMDD1 cells and did not change either NOX-2 mRNA or NOX-4 mRNA levels. These data indicate that COX-2 or a metabolite of COX-2 may increase transcription of NOX-2 and NOX-4 in MMDD1 cells upon stimulation by aldosterone. Limitations of the present study include how COX-2 is activated and whether it interacts with NOX isoforms. Molecular mechanisms, such as which COX-2-derived metabolite(s) stimulates NOX and the specific signaling pathway involved are the focus of future studies.

There are several potential sources of O2− in MD cells including uncoupled NOS, the electron transport system in mitochondria, xanthine oxidase, NAD(P)H oxidase, and COX. The primary sources for aldosterone-induced O2− in MD were COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4. Aldosterone clearly upregulated COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4, and inhibition of NAD(P)H oxidase or cyclooxygenase (Fig. 6) significantly decreased O2− production in MMDD1 cells. The data support a possible stimulatory effect of COX-2 on NOX-2 and NOX-4, since during aldosterone administration, a specific COX-2 siRNA not only decreased COX-2 mRNAs but also mRNAs of NOX-2 and NOX-4. Apocynin is a well-characterized inhibitor of NADPH oxidase. It acts by preventing serine phosphorylation of the cytosolic p47phox subunit and blocking its assembly with gp91phox in the cell membrane (8, 11, 33). Of note, apocynin has recently been reported to have antioxidant effects that are independent of NOXs (17); thus it may be reducing O2− independently of NOX inhibition. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that apocynin may affect the sources of O2− such as cytochrome P-450, mitochondria, xanthine oxidase, or uncoupled forms of NOS.

We designed these experiments to study the direct effects of aldosterone and tried to avoid the complex situation that occurs after superoxide generation. In some situations, NOX activation initiates production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and other oxidase systems often amplify this initial response. ROS can also activate NOX enzymes and increase their own production in a positive feedback loop (5, 7, 22, 23, 32, 45). We found that 30 min is the shortest time period that induces significant and consistent increases in superoxide.

Aldosterone has well-documented genomic and nongenomic effects in multiple tissues. It is believed that the genomic effects of aldosterone are mediated by the MR while nongenomic effects are independent of gene transcription (30). In Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, which share properties with renal cortical collecting duct epithelium, there was within seconds after exposure to aldosterone an increase in intracellular calcium and sodium and an increased potassium flux (12). This was likely caused by a nongenomic effect of aldosterone. In other kidney cell line, M-1 cells, aldosterone produced a rapid increase in intracellular calcium (14). Aldosterone caused constriction of perfused afferent (at 1 nM aldosterone) and efferent arterioles (at 50 nM aldosterone) (2). This constriction was blocked by inhibitors of transcription and protein translation and sprironolactone, an MR inhibitor (2). In endothelial cells, aldosterone at a concentration of 10 nM has been reported to induce superoxide generation from NAD(P)H-oxidase (21). Aldosterone has recently been shown to increase superoxide production and induce cardiovascular injury in mineralocorticoid-induced hypertensive animals, whose effects were blocked by the administration of subpressor doses of MR antagonists as well as antioxidants and/or NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitors (3, 19, 36, 37, 41).

In the present study, our data indicate that even though the effect occurred in 30 min, the changes were due to genomic effects of aldosterone. First, aldosterone's effects on MMDD1 superoxide production were completely blocked with the MR inhibitor eplerenone. Second, increases in both mRNAs and protein levels of COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 were significant in cells exposed to aldosterone. Third, the COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 mRNA changes were specifically inhibited with a COX-2 siRNA.

O2− release by MD cells can potentially increase afferent arteriolar constriction by two mechanisms. First, NO from nNOS opposes the TGF-mediated constriction of the afferent arteriole; therefore, an increase in MD O2− will scavenge NO and thus increase TGF (28, 31, 38, 43). Second, a recent study was done in microdissected afferent arterioles with adherent tubular segments containing the MD. Microperfusion of the MD-containing segments at different flow rates induced TGF. Data obtained from inhibition of NO release from nNOS with 7-nitroindazole and inhibition of O2− with tempol and comparison with afferent arteriole-damaged endothelium showed that O2− directly constricted the afferent arteriole (25).

The plasma aldosterone concentration is ∼5.6–13.9 nmol/l in human (20) and 0.8–3.33 nmol/l in mice (16). Even though the concentration of aldosterone in renal tubules is not clear, renal clearance studies have shown that aldosterone filters into the tubules, and ∼90% of filtered aldosterone is reabsorbed primarily at the distal tubule (40). In our preliminary study, we found that the MR is expressed in rat MD measured with immunohistochemistry and RT-PCR (unpublished data). We speculate that the MR in the MD is activated by aldosterone in the tubular lumen.

In summary, the MR has been found on MMDD1 cells, which mediates the increase in O2− production when exposed to aldosterone, and this prooxidant effect is blocked by eplerenone. COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4 mRNAs have been found in MMDD1 cells, and these mRNAs were significantly upregulated in the presence of aldosterone. The increase in O2− production in MMDD1 cells was blocked by inhibitors of COX-2 or NAD(P)H oxidase. In addition, in aldosterone-stimulated MMDD1 cells, a selective COX-2 siRNA not only completely blocked aldosterone-induced increases in COX-2 but also NOX-2 and NOX-4 mRNAs, suggesting that COX-2 causes increased expression of NOX-2 and NOX-4. Therefore, aldosterone, acting through the MR, can increase O2− production in MD cells via stimulation of COX-2, NOX-2, and NOX-4. The interaction between O2− and NO in the MD will determine the bioavailability of NO, which is one of the most important factors that modulate TGF and GFR. Different amounts of O2− generated by the MD under different physiological and pathophysiological situations might contribute to alter TGF. This in turn will affect renal afferent arteriolar tone, which changes GFR and renal sodium excretion and thus blood pressure.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant RO1HL-086767 and a grant from The China Scholarship Council.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Araujo M, Welch WJ. Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibition suppresses tubuloglomerular feedback: roles of thromboxane receptors and nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F790–F794, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arima S, Kohagura K, Xu HL, Sugawara A, Abe T, Satoh F, Takeuchi K, Ito S. Nongenomic vascular action of aldosterone in the glomerular microcirculation. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2255–2263, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beswick RA, Dorrance AM, Leite R, Webb RC. NADH/NADPH oxidase and enhanced superoxide production in the mineralocorticoid hypertensive rat. Hypertension 38: 1107–1111, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blantz RC, Pelayo JC. A functional role for the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism. Kidney Int 25: 739–746, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DeMarco VG, Habibi J, Whaley-Connell AT, Schneider RI, Heller RL, Bosanquet JP, Hayden MR, Delcour K, Cooper SA, Andresen BT, Sowers JR, Dellsperger KC. Oxidative stress contributes to pulmonary hypertension in the transgenic (mRen2)27 rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2659–H2668, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deng A, Wead LM, Blantz RC. Temporal adaptation of tubuloglomerular feedback: effects of COX-2. Kidney Int 66: 2348–2353, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. El JA, Valente AJ, Lechleiter JD, Gamez MJ, Pearson DW, Nauseef WM, Clark RA. Novel redox-dependent regulation of NOX5 by the tyrosine kinase c-Abl. Free Radic Biol Med 44: 868–881, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ergul A, Johansen JS, Strømhaug C, Harris AK, Hutchinson J, Tawfik A, Rahimi A, Rhim E, Wells B, Caldwell RW, Anstadt MP. Vascular dysfunction of venous bypass conduits is mediated by reactive oxygen species in diabetes: role of endothelin-1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313: 70–77, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fu Y, Katsuya T, Matsuo A, Yamamoto K, Akasaka H, Takami Y, Iwashima Y, Sugimoto K, Ishikawa K, Ohishi M, Rakugi H, Ogihara T. Relationship of bradykinin B2 receptor gene polymorphism with essential hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertens Res 27: 933–938, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fu Y, Zhang R, Lu D, Liu H, Chandrashekar K, Juncos LA, Liu R. NOX2 is the primary source of angiotensin II-induced superoxide in the macula densa. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R707–R712, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gao WD, Liu Y, Marban E. Selective effects of oxygen free radicals on excitation-contraction coupling in ventricular muscle. Implications for the mechanism of stunned myocardium. Circulation 94: 2597–2604, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gekle M, Golenhofen N, Oberleithner H, Silbernagl S. Rapid activation of Na+/H+ exchange by aldosterone in renal epithelial cells requires Ca2+ and stimulation of a plasma membrane proton conductance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 10500–10504, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gomez-Sanchez CE, de Rodriguez AF, Romero DG, Estess J, Warden MP, Gomez-Sanchez MT, Gomez-Sanchez EP. Development of a panel of monoclonal antibodies against the mineralocorticoid receptor. Endocrinology 147: 1343–1348, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harvey BJ, Higgins M. Nongenomic effects of aldosterone on Ca2+ in M-1 cortical collecting duct cells. Kidney Int 57: 1395–1403, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. He H, Podymow T, Zimpelmann J, Burns KD. NO inhibits Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport via a cytochrome P-450-dependent pathway in renal epithelial cells (MMDD1). Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F1235–F1244, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heitzmann D, Derand R, Jungbauer S, Bandulik S, Sterner C, Schweda F, El WA, Lalli E, Guy N, Mengual R, Reichold M, Tegtmeier I, Bendahhou S, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Aller MI, Wisden W, Weber A, Lesage F, Warth R, Barhanin J. Invalidation of TASK1 potassium channels disrupts adrenal gland zonation and mineralocorticoid homeostasis. EMBO J 27: 179–187, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heumuller S, Wind S, Barbosa-Sicard E, Schmidt HH, Busse R, Schroder K, Brandes RP. Apocynin is not an inhibitor of vascular NADPH oxidases but an antioxidant. Hypertension 51: 211–217, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heylen E, Huang A, Sun D, Kaley G. Nitric oxide-mediated dilation of arterioles to intraluminal administration of aldosterone. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 54: 535–542, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirono Y, Yoshimoto T, Suzuki N, Sugiyama T, Sakurada M, Takai S, Kobayashi N, Shichiri M, Hirata Y. Angiotensin II receptor type 1-mediated vascular oxidative stress and proinflammatory gene expression in aldosterone-induced hypertension: the possible role of local renin-angiotensin system. Endocrinology 148: 1688–1696, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hollenberg NK, Stevanovic R, Agarwal A, Lansang MC, Price DA, Laffel LM, Williams GH, Fisher ND. Plasma aldosterone concentration in the patient with diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int 65: 1435–1439, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iwashima F, Yoshimoto T, Minami I, Sakurada M, Hirono Y, Hirata Y. Aldosterone induces superoxide generation via Rac1 activation in endothelial cells. Endocrinology 149: 1009–1014, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lassegue B, Griendling KK. Reactive oxygen species in hypertension; an update. Am J Hypertens 17: 852–860, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li Q, Zhang Y, Marden JJ, Banfi B, Engelhardt JF. Endosomal NADPH oxidase regulates c-Src activation following hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Biochem J 411: 531–541, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu R, Carretero OA, Ren Y, Wang H, Garvin JL. Intracellular pH regulates superoxide production by the macula densa. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F851–F856, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu R, Garvin JL, Ren Y, Pagano PJ, Carretero OA. Depolarization of the macula densa induces superoxide production via NAD(P)H oxidase. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1867–F1872, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu R, Persson AE. Simultaneous changes of cell volume and cytosolic calcium concentration in macula densa cells caused by alterations of luminal NaCl concentration. J Physiol 563: 895–901, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu R, Pittner J, Persson AE. Changes of cell volume and nitric oxide concentration in macula densa cells caused by changes in luminal NaCl concentration. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2688–2696, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu R, Ren Y, Garvin JL, Carretero OA. Superoxide enhances tubuloglomerular feedback by constricting the afferent arteriole. Kidney Int 66: 268–274, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lombes M, Farman N, Oblin ME, Baulieu EE, Bonvalet JP, Erlanger BF, Gasc JM. Immunohistochemical localization of renal mineralocorticoid receptor by using an anti-idiotypic antibody that is an internal image of aldosterone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 1086–1088, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Losel R, Schultz A, Wehling M. A quick glance at rapid aldosterone action. Mol Cell Endocrinol 217: 137–141, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lu D, Fu Y, Lopez-Ruiz A, Zhang R, Juncos R, Liu H, Manning RD, Jr, Juncos LA, Liu R. Salt-sensitive splice variant of nNOS expressed in the macula densa cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F1465–F1471, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Manning RD, Jr, Tian N, Meng S. Oxidative stress and antioxidant treatment in hypertension and the associated renal damage. Am J Nephrol 25: 311–317, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meyer JW, Schmitt ME. A central role for the endothelial NADPH oxidase in atherosclerosis. FEBS Lett 472: 1–4, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Paliege A, Pasumarthy A, Mizel D, Yang T, Schnermann J, Bachmann S. Effect of apocynin treatment on renal expression of COX-2, NOS1, and renin in Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R694–R700, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rebsamen MC, Perrier E, Gerber-Wicht C, Benitah JP, Lang U. Direct and indirect effects of aldosterone on cyclooxygenase-2 and interleukin-6 expression in rat cardiac cells in culture and after myocardial infarction. Endocrinology 145: 3135–3142, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rudolph AE, Rocha R, McMahon EG. Aldosterone target organ protection by eplerenone. Mol Cell Endocrinol 217: 229–238, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schiffrin EL. Effects of aldosterone on the vasculature. Hypertension 47: 312–318, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schnermann J, Levine DZ. Paracrine factors in tubuloglomerular feedback: adenosine, ATP, and nitric oxide. Annu Rev Physiol 65: 501–529, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schnermann J, Ploth DW, Hermle M. Activation of tubulo-glomerular feedback by chloride transport. Pflügers Arch 362: 229–240, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scurry MT, Shear L, Barry KG. The renal tubular handling of aldosterone and its acid-labile conjugate. J Clin Invest 47: 242–248, 1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sun Y, Zhang J, Lu L, Chen SS, Quinn MT, Weber KT. Aldosterone-induced inflammation in the rat heart. Role of oxidative stress. Am J Pathol 161: 1773–1781, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Traynor TR, Smart A, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Inhibition of macula densa-stimulated renin secretion by pharmacological blockade of cycloooxygenase-2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277: F706–F710, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Tubuloglomerular feedback and macula densa-derived NO. In: Nitric Oxide and the Kidney. Physiology and Pathophysiology, edited by Goligorsky MS, Gross SS. New York: Chapman & Hall, 1997, p. 216–232 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang T, Park JM, Arend L, Huang Y, Topaloglu R, Pasumarthy A, Praetorius H, Spring K, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Low chloride stimulation of prostaglandin E2 release and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in a mouse macula densa cell line. J Biol Chem 275: 37922–37929, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yoshimoto T, Fukai N, Sato R, Sugiyama T, Ozawa N, Shichiri M, Hirata Y. Antioxidant effect of adrenomedullin on angiotensin II-induced reactive oxygen species generation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Endocrinology 145: 3331–3337, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang R, Harding P, Garvin JL, Juncos R, Peterson E, Juncos LA, Liu R. Isoforms and functions of NADPH oxidase at the macula densa. Hypertension 53: 556–563, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.