Abstract

Although recent data suggest that some long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) exert widespread effects on gene expression and organelle formation, lncRNAs as a group constitute a sizable but poorly characterized fraction of the human transcriptome. We investigated whether some human lncRNA sequences were fortuitously represented on commonly used microarrays, then used this annotation to assess lncRNA expression in human brain. A computational and annotation pipeline was developed to identify lncRNA transcripts represented on Affymetrix U133 arrays. A previously published dataset derived from human nucleus accumbens (hNAcc) was then examined for potential lncRNA expression. Twenty-three lncRNAs were determined to be represented on U133 arrays. Of these, dataset analysis revealed that five lncRNAs were consistently detected in samples of hNAcc. Strikingly, the abundance of these lncRNAs was upregulated in human heroin abusers compared to matched drug-free control subjects, a finding confirmed by quantitative PCR. This study presents a paradigm for examining existing Affymetrix datasets for the detection and potential regulation of lncRNA expression, including changes associated with human disease. The finding that all detected lncRNAs were upregulated in heroin abusers is consonant with the proposed role of lncRNAs as mediators of widespread changes in gene expression as occurs in drug abuse.

Keywords: MIAT, MALAT1, MEG3, NEAT1, lncRNA, nucleus accumbens

As a result of genome sequencing, it is evident that humans possess roughly the same number of protein-coding genes as simpler multicellular organisms despite quite obvious differences in biological complexity. Furthermore, only a small proportion (~2%) of mammalian genomes encodes protein-coding mRNAs, whereas a much greater proportion is transcribed as noncoding RNAs (Wilusz et al. 2009; Guttman et al. 2009; Taft et al. 2010). Over the past decade, a great deal of attention has been devoted to short regulatory ncRNAs (e.g. microRNAs and small interfering RNAs); whereas long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs; generally defined as >200nt), though hypothesized to contribute to biological complexity, are less well understood. LncRNAs have been categorized in terms of localization relative to protein-coding genes (e.g. intergenic, intronic, cis-antisense), splicing and polyadenylation status, and extent of their sequence conservation, although the utility of these broad classifications remains unclear. In terms of functionality, some lncRNAs seem to function as epigenetic regulators of gene expression (including imprinting) via chromatin remodeling, others directly regulate the expression of individual genes through various transcriptional or post-transcriptional mechanisms, whereas still other lncRNAs have been implicated in organelle formation or intracellular trafficking (Wilusz et al. 2009; Guttman et al. 2009; Taft et al. 2010). Because of the variety of regulatory functions they perform, lncRNAs seem to be particularly well-positioned to exert widespread effects on patterns of gene and protein expression.

In addition to sequence conservation, the precise temporal and cellular specificity of lncRNA expression is considered prima facie evidence of their functional importance. Nowhere is this more evident than in the CNS, where scores of lncRNAs exhibit robust and specific expression patterns and likely influence brain development, neurotransmission, and neuropsychiatric disorders (Mercer et al. 2008; Qureshi et al. 2010). Although our understanding in this regard is rudimentary, a recent study (Faghihi et al. 2008) found that one particular lncRNA is directly implicated in the increased CNS abundance of Aβ 1–42 seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

In the course of our previous Affymetrix microarray studies of postmortem brain from human drug abusers, (Albertson et al. 2006) we found that one of the transcripts most robustly increased by drug abuse was derived from a gene assumed to encode a hypothetical protein (LOC150271). Subsequent bioinformatic analysis has revealed that this transcript does not encode a protein but actually corresponds to a known lncRNA, MIAT (Ishii et al. 2006). Given the proposed role of some lncRNAs as top-down regulators of gene expression, and the widespread changes in gene expression seen in drug abuse (Albertson et al. 2006; Lehrmann and Freed 2008), we developed a computational and manual annotation pipeline to identify additional lncRNA transcripts represented on Affymetrix arrays. We went on to determine the lncRNAs expressed in human nucleus accumbens (hNAcc) and, of these, which show altered abundance in heroin abusers. This study reveals that the expression of numerous lncRNAs is unusually responsive to heroin abuse, and presents a paradigm for examining existing Affymetrix datasets for disease-related changes in lncRNA expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

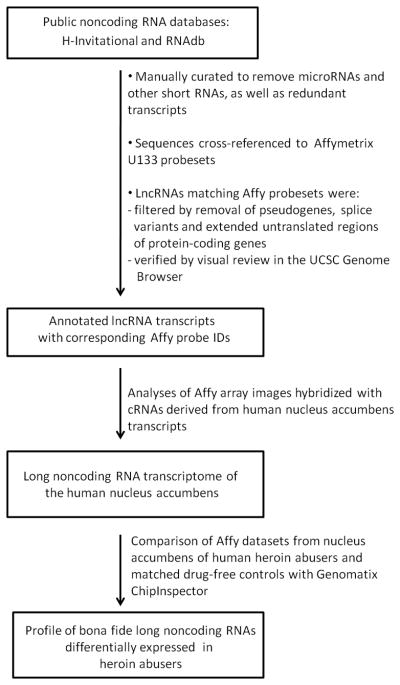

In order to assess the expression of lncRNAs, we generated a computational pipeline to identify lncRNAs represented on Affymetrix arrays (Figure 1). Briefly, the public RNA databases RNAdb (Pang et al. 2005) and H-Invitational (Yamasaki et al. 2008) (HI) were curated to generate a list of lncRNAs (i.e. excluding short RNAs such as tRNA or microRNAs). This list was then mapped to Affymetrix U133 probesets and transcripts annotated using the University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser (Kent et al. 2002). Microarray data available from a previously published study of human postmortem brain (Albertson et al. 2006) were then reanalyzed to assess the basal expression of curated lncRNAs in hNAcc and differential expression in heroin abusers relative to matched drug-free control subjects. LncRNA microarray data were verified by quantitative real time-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). For more detail about the computational pipeline, please read below.

Figure 1.

An overview of the long noncoding RNA computational pipeline developed to analyze Affymetrix U133 datasets.

NCBI resource access

National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Entrez Nucleotide search (GenBank database search) was accessed at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; nucleotide BLAST search (BLASTN) was accessed at http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, Nucleotide BLAST. The options were: Database = Others, nucleotide collection (nr/nt); Program Selection BLASTN., with the nr/nt option.

Public ncRNA databases

H--Invitational version 5 (Yamasaki et al. 2008) was accessed at http://www.h-invitational.jp. The advanced search options were: Dataset = Representative H-Inv Transcripts; Genome Location (now named Gene Structures in version 6) = all chromosomes except Y, M, UM, hapmap; Coding Potential (now named Transcript Info in version 6) = Non-protein-coding transcripts only; Classification of ncRNA (now Non-coding functional RNAs) = all options selected; Curation status = all options selected. The query retrieved 578 transcripts. RNAdb (Pang et al. 2005) was accessed at http://research.imb.uq.edu.au/rnadb/. The options were: Curated from literature; Species = Homo sapiens. The query retrieved 531 transcripts that were text-searched for microRNA, miRNA, rRNA, tRNA, pseudogene, snRNA, and snoRNA. Transcripts whose annotation appeared to indicate pseudogenes or known short RNAs or host genes thereof were excluded. Only the remaining transcripts with GenBank accession numbers were used for subsequent analyses.

UCSC Genome Browser and Genome Database resources

The University of California at Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser (Kent et al. 2002) was accessed at http://genome.ucsc.edu. BLAT (Kent 2002) sequence search was accessed at http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgBlat. All analysis was done on the Human, Mar. 2006 (hg18) assembly. For matching cDNA GenBank accession numbers and Affymetrix U133 A and B probeset IDs, the UCSC Genome Database (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg18/database/) resource files all_mrna.txt and affyU133.txt, respectively, were parsed.

Matching database ncRNAs to Affymetrix probesets

For each transcript from the filtered HI and RNAdb retrievals, chromosome, genomic strand (transcription orientation along the genome), starting coordinate, and ending coordinate were retrieved from the UCSC all_mrna table. The UCSC affyU133 resource contains genomic coordinate information in the same format for each probeset ID from the U133 A and B arrays. All transcripts that mapped unambiguously (based on the genomic coordinates) to Affy probesets were included in this study. Affy probe mapping for HI transcripts was also verified by using the Net.Affx search tool (http://www.affymetrix.com/analysis/index.affx) with UCSC BLAT to confirm that at least one individual probe per probeset overlapped with the transcript on the same genomic strand.

UCSC-based manual curation of Affymetrix-represented lncRNA hits

The lists of Affymetrix-matched lncRNA hits were sorted to exclude redundancies in accession numbers or genomic positions. The remaining Affymetrix-matching lncRNAs were curated with the UCSC Genome Browser displaying the following UCSC Tracks in Pack mode: UCSC Genes, RefSeq Genes, Ensembl Genes, sno/miRNA, Human mRNAs, Human ESTs, Affy U133, Conservation, and RepeatMasker. This manual curation verified that these lncRNA-Affymetrix matches were nonredundant, bona fide lncRNA genes. Transcribed pseudogenes, alternative splice products of protein-coding genes, extended untranslated regions (UTRs) of protein-coding genes, and microRNA host genes were excluded.

Affymetrix Microarray Dataset

Subjects and microarray methods used to obtain this published dataset were described in detail (Albertson et al. 2006). Briefly, nucleus accumbens RNA was extracted from 6 drug-free control subjects and 6 heroin-abusing subjects closely matched for age, race, sex and tissue pH. Total RNA abundance, several measures of RNA quality and efficiencies of cRNA generation and hybridization to Affymetrix U133A and U133B chips did not differ between the control and drug cohorts, which were processed in parallel at each step (Albertson et al. 2006).

Bioconductor microarray analysis

We used the Affy Bioconductor package in the R language (Gentleman et al. 2004) (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/vignettes/affy/inst/doc/affy.pdf) to implement the Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5.0 (MAS5) algorithm on the Affymetrix CEL files corresponding to the subjects from our previous study (Albertson et al. 2006), using the options (bgcorrect.method=“mas”, normalize.method=“qspline”, pmcorrect.method=“mas”, summary.method=“mas”). For our analyses, a given transcript was considered detected if at least one individual probe received a present call in all 6 of the control subjects. This criterion was selected on the basis of initial experiments in which we were able to validate microarray data by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) for 4 transcripts that were detected in all of the control samples. One transcript, SRA-1, was detected in all but one of the control subjects, narrowly missing our criterion for detection. To verify that curated lncRNAs not detected in the NAcc were, in fact, detectable using the corresponding Affymetrix probes, these Affymetrix probe IDs were input into the Gene Expression Omnibus database [(Edgar et al. 2002); http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geoprofiles/] along with the search term brain to demonstrate transcript detection in other human brain regions.

ChipInspector microarray analysis

Affymetrix CEL files corresponding to the subjects from our previous study (Albertson et al. 2006) were imported into Genomatix ChipInspector software, version 2 (ElDorado database version: E20R0903). All 12 subjects were analyzed using the group-wise exhaustive analysis with False Discovery Rate =0 and 3-probe minimum coverage required. In addition to the transcripts discussed below that were both consistently detected and differentially expressed, one additional lncRNA, SMAD5OS (aka DAMS (Zavadil et al. 1999)), was expressed in most but not all subjects and showed a trend towards a group-wise difference in expression levels (not shown).

QRTPCR validation of microarray results

Methods used for qRT-PCR were described previously (Albertson et al. 2006). Briefly, RNA from the subjects used in the initial microarray study was used for verification of the microarray data. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed (Sensiscript RT Kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with random hexamer primers. PCR was performed in the LightCycler version 3.3 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) with the Qiagen SYBR Green PCR Kit as described previously following the manufacturers’ protocol. Equivalent amounts of RNA from each subject were pooled to create standard curves (input RNA 1–16ng) that were assayed in parallel with replicate samples (5ng RNA) from individual subjects. A linear standard curve was generated and all samples fell within the range of the curve. For sample normalization, individual transcript values were divided by the subject's -actin values determined using the same RT reaction. -Actin transcript levels did not differ between heroin abusers and control subjects, as determined by either RT-PCR (p=0.85) or microarray (p=0.10). Differences in transcript abundance between heroin abusers and matched controls were assessed by paired t-tests. (This analysis was performed on only 5 of 6 pairs of subjects due to initial failure of the RT reaction for one subject and insufficient remaining RNA to repeat the reaction.) The PCR primers used for this study were: NEAT2 5′-GCCTGTTACGGTTGGGATTG-3′ and 5′-TGGGAGTTACTTGCCAACTTG-3′ (bases 4115-4256 of accession EF177381.1) ; NEAT1 5′-GACGAGATTAGATGGGCTCTTCTG-3′ and 5′-CGACCAAACACAGAAAAGACAACA-3′ (bases 575-734 of accession AF001893.1) ; MEG3 5′-TGGATGCCTACGTGGGAAGG-3′ and 5′-AGAGGGCGGGTCTCTACTCAAGG-3′ (bases 1314-1476 of accession AY314975.1); MIAT 5′-GGAGGCATCTAAGCTGAGCTGTG-3′ and 5′-CGGCACCATGTCCATGTCTC-3′ (bases 8644-8808 of accession AB263417). Pearson correlations between Affymetrix microarray data (signal log ratio calculated with MAS5) and qRT-PCR data were performed with GraphPadPrism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

The lncRNA MIAT is upregulated in heroin abusers

In our previously published study (Albertson et al. 2006), pair-wise comparisons of transcript levels from postmortem hNAcc of heroin abusers were made relative to matched controls. One of the top regulated transcripts identified corresponded to the hypothetical protein LOC150271 gene. Updated annotation has since revealed that LOC150271 corresponds to GenBank accession number XM_097859.4 which, in turn, shows 100% identity with the lncRNA MIAT.

Identification of additional lncRNAs represented by Affymetrix probesets

Detection and differential expression of MIAT in heroin abusers led us to investigate whether other lncRNAs are also unknowingly represented on Affymetrix U133 arrays. Utilizing two prominent public databases: (H-Invitational v 5.0 and RNAdb v2) and our computational pipeline (see Materials and Methods and Fig. 1), we identified 23 nonredundant, documented lncRNAs that are represented on Affymetrix U133 arrays (Tables 1 & 2). For each lncRNA, any additional designations used in rodent or human are notated.

Table 1.

Long noncoding RNAs represented on Affymetrix U133 arrays that were not consistently detected in human nucleus accumbens

Entrez Gene ID, alternative gene names (in human or other species), corresponding accession numbers and Affymetrix U133 probe IDs are indicated. Those lncRNAs detected in hNAcc are listed in Table 2.

| Entrez Gene ID | lncRNA genes | Accession numbers | Affymetrix probe IDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAA1 | lncRNA from asthma-associated region 1 | AY312365-AY312373 | U133B:234117_at |

| DIO3-OS | deiodinase, iodothyronine, type III opposite strand | AF469201 | U133B:239727_at |

| GNAS-AS | guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha stimulating antisense RNA | AJ251759 | U133B:232881_at |

| LOC750631 | P53 INTRONIC NCRNA | U58658 | U133B:224185_at |

| PCA3 | prostate cancer antigen 3 | AF103907 | U133B:232575_at |

| PCGEM1 | noncoding prostate-specific transcript 1 | AF223389 | U133B:234529_at |

| pregnancy-induced hypertension syndrome-related | AF232216 | U133B:234822_at | |

| PRINS | psoriasis susceptibilty-related gene | AK022045 | U133B:242846_at |

| SRA1 | steroid receptor RNA activator 1 noncoding splice variant also known as SRA, SRAP, STRAA1, pp7684, MGC87674 | AF293024-26 | U133B:224864_at U133B:224130_s_at |

| TTTY12 | testis-specific transcript, y-linked 12 | AF332241 | U133B:224195_at |

| SMAD5OS | SMAD family member 5 opposite strand (also known as DAMS) | AF086556 | U133A:220263_at |

| previously unknown lncRNA | AY927572, AY927579 | U133B:237480_at | |

| LOC440432 | clone DKFZp564H213 | AL049275 | U133B:234787_at |

| clone DKFZp564E202 | AL049986 | U133B:235826_at | |

| clone IMAGE:5723825 | BC033874 | U133B:235534_at | |

| clone CS0DI009YA14 | CR613972 | U133B:227044_at | |

| clone JKA5 mRNA induced upon T cell activation | U38434 | U133B:237664_at | |

| clone ZD68B12 | AF086375 | U133B:230302_at |

Table 2.

Long noncoding RNAs represented on Affymetrix U133 arrays that were reliably detected in human nucleus accumbens

An lncRNA was considered reliably detected in human NAcc if at least one probe corresponding to the transcript gave a specific signal in all control subjects. No transcripts undetected in the controls were consistently detected in drug abusers.

| Entrez Gene ID | lncRNA genes | Accession numbers | Affymetrix probe IDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIAT | myocardial infarction associated transcript also known as rncr2, gomafu, C22orf35, FLJ25887, FLJ25967, FLJ38367 FLJ45323 | AB263417 | U133B:227168_at U133B:237322_at U133B:232340_at U133B:237429_at U133B:228658_at |

| MEG3 | maternally expressed gene 3 also known as GTL2, FLJ31163, FLJ42589, FP504, NCRNA00023, PRO0518 PRO2160, prebp1 |

AY314975.1 AY927554 |

U133A:210794_s_at U133B:226210_s_at U133B:226211_at U133B:227390_at U133B:235077_at |

| NEAT1 | nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1 also known as nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1, TncRNA, NCRNA00084, MEN epsilon/beta, VINC-1 |

AF001892.1 AF001893.1 AF080092 AF508303 |

U133B:224565_at U133B:224566_at U133A:214657_s_at U133B:227062_at U133B:234989_at U133B:238320_at U133B:225239_at U133B:239269_at |

| NEAT2 | nuclear enriched abundant transcript 2 also known as MALAT1 - metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1, NCRNA00047, PRO2853, HCN |

EF177381.1 CR606626 BC025986 BX538238 FJ209305 BC104662 BC063689 AK130345 CR595720 AL050210 |

U133B:223940_x_at U133B:224567_x_at U133B:224568_x_at U133B:226675_s_at U133B:224559_at U133B:224558_s_at |

| EMX2OS | empty spiracles homeobox 2 opposite strand also known as NCRNA00045, FLJ41539 |

AY117034 AY117413 |

U133B:230963_at U133B:232531_at |

Human NAcc lncRNA expression profile

To date, there are few studies of lncRNA expression in the human brain, despite an abundance of rodent studies (Qureshi et al. 2010 and references therein). We therefore examined our previously published Affymetrix microarray dataset (Albertson et al. 2006) using analysis with Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5.0 to determine the expression of these 23 Affymetrix-represented lncRNAs in hNAcc. Of the 23 lncRNAs represented on the Affymetrix U133 arrays, we determined that 18 were not consistently expressed in hNAcc (Table 1).

In contrast, 5 of the 23 Affy-represented lncRNAs were reproducibly detected in all of the control subjects in the hNAcc (Table 2). A search of the Gene Expression Omnibus database revealed that all 18 lncRNAs not consistently expressed in hNAcc were detected in the cerebellar cortex (GSE4036), entorhinal cortex (GSE4757) and substantia nigra (GSE8397) (Moran et al. 2006); one (SMAD5OS) was also detected in prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex (GSE5388 and GSE5389). Thus all of the curated lncRNA transcripts represented by Affymetrix probes can be detected in at least some regions of human brain. We went on to examine that lncRNA subset expressed in hNAcc.

Differential expression of Affymetrix-represented lncRNAs in hNAcc of heroin abusers

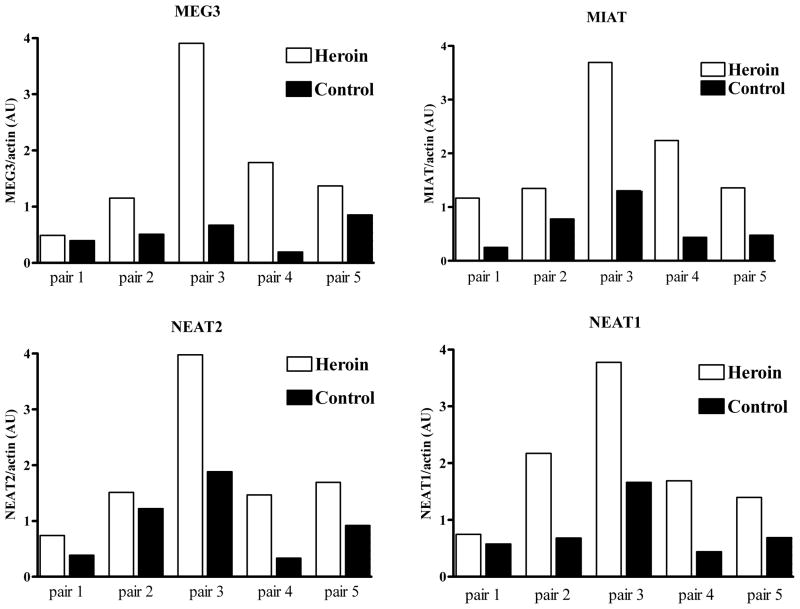

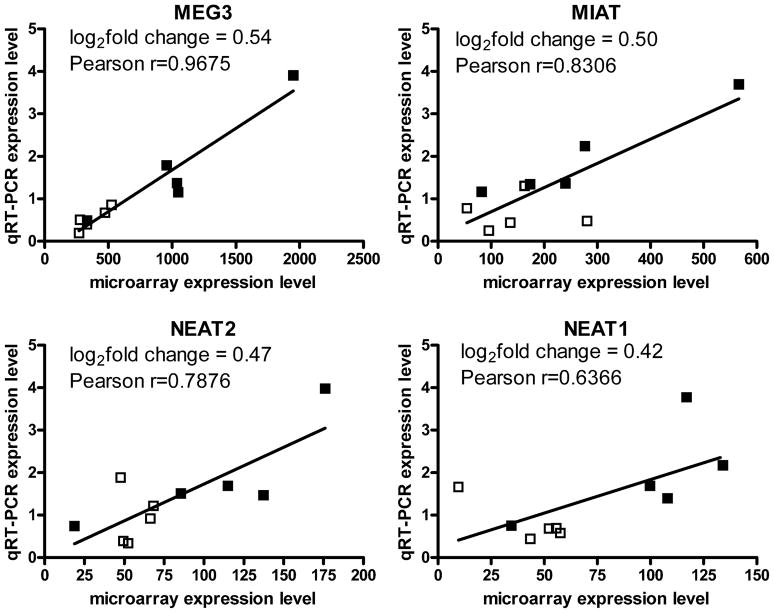

In light of this lncRNA annotation, we reexamined the Affymetrix Microarray Suite data from our previous (Albertson et al., 2006) pair-wise analysis of heroin abusers and controls. We found that four lncRNAs were upregulated in heroin abusers compared to matched, drug-free controls: MIAT, NEAT1, NEAT2, and MEG3. Differential expression of these lncRNAs was validated by qRT-PCR (Figure 2) and positively correlated with the previous Affymetrix microarray data (Figure 3). A subsequent group-wise analysis of the microarray data (performed with Genomatix ChipInspector) similarly identified changes in these four lncRNAs as well as an additional upregulated lncRNA (EMX2OS, log2fold change=0.35; not validated by RT-PCR due to exhaustion of sample). Thus each lncRNA consistently detected in the hNAcc of control subjects (Table 2) was also upregulated in matched heroin abusing subjects (Figures 2 & 3).

Figure 2.

qRT-PCR validation of four long noncoding RNAs differentially expressed between heroin abusers and matched controls. LncRNA abundances were corrected for actin transcript levels in the same sample and RT reaction. Black bars- control subjects, white bars- heroin subjects. For all four target genes, p<0.05 by paired t-test. AU-arbitrary units.

Figure 3.

Significant correlation between lncRNA transcript abundance as seen in Affymetrix microarray data and by qRT-PCR. □-control subjects, ■-heroin subjects. Log2fold change shown is calculated from the ChipInspector group-wise analysis. Microarray data for probes 223940_x_at, 224566_at, 210794_s_at, 227168_at were used for NEAT2, NEAT1, MEG3 and MIAT, respectively. For all correlations, p<0.03.

DISCUSSION

We have described the annotation of probe IDs for 23 lncRNAs unknowingly but fortuitously included in the design of Affymetrix U133 microarrays, which have been commonly used to produce gene expression profiles of human tissues, cell lines and disease states. While representing only a fraction of the lncRNAs encoded by the human genome, (Wilusz et al. 2009; Guttman et al. 2009; Taft et al. 2010) our analysis showed that ~20% of the Affymetrix-represented lncRNAs were reliably detected in postmortem hNAcc, and those not found in the hNAcc were all expressed in some other regions of human brain. Our present finding that all lncRNAs reliably detected in hNAcc were upregulated in heroin abusers contrasts with our previous analysis (Albertson et al. 2006) of the same dataset, which showed that overall ~50% of the total transcripts represented on the arrays were expressed in hNAcc but only ~5% of these differentially expressed between heroin users and controls. While the low number of lncRNAs present in the dataset might bias these calculations, these results seem consistent with the proposed role of lncRNAs as top-down regulators of gene expression (Taft et al. 2010; Wilusz et al. 2009; Guttman et al. 2009).

What do we know about the five heroin-regulated lncRNAs (Table 2)? MEG3 is a well-studied cAMP-responsive (Zhao et al. 2006) maternally imprinted lncRNA expressed in the nuclei of select populations of neurons in the brain (McLaughlin et al. 2006). MEG3 is upregulated during GABA neuron neurogenesis (Mercer et al. 2010) and MEG3 knockout mice have increased brain microvessel formation and altered expression of angiogenesis genes (Gordon et al. 2010). Some of the alternatively spliced MEG3 transcripts are transcriptional co-activators (Zhang et al. 2010). Intriguingly a genome-wide association study has implicated MEG3 in the vulnerability to heroin addiction (Nielsen et al. 2008).

The lncRNA EMX2OS is generated from the opposite strand of the homeodomain transcription factor EMX2 gene in neuronal precursor cells (Noonan et al. 2003). EMX2OS post-transcriptionally regulates the abundance of the coding transcript, thereby regulating activity of EMX2 (Spigoni et al. 2010).

Though discovered initially in other biological contexts, NEAT1 and NEAT2 are known to be expressed in the brain (Hutchinson et al. 2007). NEAT1 and NEAT2 are associated with nuclear paraspeckles (Wilusz et al. 2009) and speckles, respectively, (Bond and Fox 2009) ribonucleoprotein structures found in the nuclei of differentiated mammalian cells that appear to regulate the nuclear retention of select mRNAs and pre-mRNA splicing, respectively, allowing for rapid post-transcriptional regulation of expression of certain genes (Bond and Fox 2009). Significantly, NEAT2 appears to regulate synaptic density and mRNA levels of multiple synaptic genes in cultured hippocampal neurons (Bernard et al. 2010).

MIAT, originally found associated with increased risk for myocardial infarction (Ishii et al. 2006) is distributed in a spotty pattern throughout the nucleoplasm of a subset of neurons as a component of the nuclear matrix that does not involve the nucleolus, nuclear speckles, paraspeckles or coiled bodies, and thus appears novel. MIAT expression was also recently shown to be altered during development of the oligodendrocyte lineage (Mercer et al. 2010).

The purpose of this study was, first, to assess the representation of lncRNAs from public databases on a widely used commercial microarray platform (Affymetrix U133). Using this annotation, we then examined an existing dataset to determine if these lncRNAs were expressed in a human brain region of interest and differentially expressed in a human drug-abusing cohort. Interestingly, all of the small group of lncRNAs represented on the platform and reliably detected in hNAcc were upregulated in heroin abusers. Preliminary examination of a published (Albertson et al., 2004) dataset from cocaine abusers indicates a similar upregulation of many of the same transcripts (log2fold increases 0.23–0.32 for NEAT2, MIAT, MEG3 and EMX2OS; data not shown), suggesting a commonality of response across drug-abusing cohorts.

In turn, 3 of these 5 lncRNAs (MIAT, NEAT1 and NEAT2) are associated with novel nuclear domains, suggesting that modification of nuclear domains may, at least in part, underlie the much broader alterations in gene expression we previously observed within the hNAcc of heroin abusers (Albertson et al. 2006) More generally, lncRNA-related nuclear modifications may play a role in neural adaptation to environment changes (e.g. drug abuse) through rapid post-transcriptional changes in gene expression. These preliminary observations, arising from annotation of lncRNAs represented on Affymetrix arrays, suggest that a re-examination of published datasets could provide important new insights into the roles of these lncRNAs into the regulation of the human genome.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jian Wang for his contribution to the preliminary work that led to this publication. This work was supported by NIH grants DA026021 to L.L., DA006470 to M.J.B. and NS026081 to G.K. All authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- lncRNAs

long noncoding RNAs

- hNAcc

human nucleus accumbens

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real time-polymerase chain reaction

References

- Albertson DN, Schmidt CJ, Kapatos G, Bannon MJ. Distinctive profiles of gene expression in the human nucleus accumbens associated with cocaine and heroin abuse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2304–2312. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertson DN, Pruetz B, Schmidt CJ, Kuhn DM, Kapatos G, Bannon MJ. Gene Expression profile of the nucleus accumbens of human cocaine abusers: evidence for dysregulation of myelin. J Neurochem. 2004;88:1211–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard D, Prasanth KV, Tripathi V, et al. A long nuclear-retained non-coding RNA regulates synaptogenesis by modulating gene expression. EMBO J. 2010;29:3082–3093. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond CS, Fox AH. Paraspeckles: nuclear bodies built on long noncoding RNA. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:637–644. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faghihi MA, Modarresi F, Khalil AM, et al. Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of beta-secretase. Nat Med. 2008;14:723–730. doi: 10.1038/nm1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon FE, Nutt CL, Cheunsuchon P, Nakayama Y, Provencher KA, Rice KA, Zhou Y, Zhang X, Klibanski A. Increased expression of angiogenic genes in the brains of mouse meg3-null embryos. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2443–2452. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M, Amit I, Garber M, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson JN, Ensminger AW, Clemson CM, Lynch CR, Lawrence JB, Chess A. A screen for nuclear transcripts identifies two linked noncoding RNAs associated with SC35 splicing domains. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii N, Ozaki K, Sato H, et al. Identification of a novel non-coding RNA, MIAT, that confers risk of myocardial infarction. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:1087–1099. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. BLAT--the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrmann E, Freed WJ. Transcriptional correlates of human substance use. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1139:34–42. doi: 10.1196/annals.1432.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin D, Vidaki M, Renieri E, Karagogeos D. Expression pattern of the maternally imprinted gene Gtl2 in the forebrain during embryonic development and adulthood. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:394–399. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Sunkin SM, Mehler MF, Mattick JS. Specific expression of long noncoding RNAs in the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:716–721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706729105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer TR, Qureshi IA, Gokhan S, Dinger ME, Li G, Mattick JS, Mehler MF. Long noncoding RNAs in neuronal-glial fate specification and oligodendrocyte lineage maturation. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran LB, Duke DC, Deprez M, Dexter DT, Pearce RK, Graeber MB. Whole genome expression profiling of the medial and lateral substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Neurogenetics. 2006;7:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10048-005-0020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen DA, Ji F, Yuferov V, Ho A, Chen A, Levran O, Ott J, Kreek MJ. Genotype patterns that contribute to increased risk for or protection from developing heroin addiction. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:417–428. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan FC, Goodfellow PJ, Staloch LJ, Mutch DG, Simon TC. Antisense transcripts at the EMX2 locus in human and mouse. Genomics. 2003;81:58–66. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(02)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang KC, Stephen S, Engstrom PG, Tajul-Arifin K, Chen W, Wahlestedt C, Lenhard B, Hayashizaki Y, Mattick JS. RNAdb--a comprehensive mammalian noncoding RNA database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D125–D130. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi IA, Mattick JS, Mehler MF. Long non-coding RNAs in nervous system function and disease. Brain Res. 2010;1338:20–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spigoni G, Gedressi C, Mallamaci A. Regulation of Emx2 expression by antisense transcripts in murine cortico-cerebral precursors. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft RJ, Pang KC, Mercer TR, Dinger M, Mattick JS. Non-coding RNAs: regulators of disease. J Pathol. 2010;220:126–139. doi: 10.1002/path.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilusz JE, Sunwoo H, Spector DL. Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1494–1504. doi: 10.1101/gad.1800909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki C, Murakami K, Fujii Y, et al. The H-Invitational Database (H-InvDB), a comprehensive annotation resource for human genes and transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D793–D799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavadil J, Svoboda P, Liang H, Kottickal LV, Nagarajan L. An antisense transcript to SMAD5 expressed in fetal and tumor tissues. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;255:668–672. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Rice K, Wang Y, Chen W, Zhong Y, Nakayama Y, Zhou Y, Klibanski A. Maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3) noncoding ribonucleic acid: isoform structure, expression, and functions. Endocrinology. 2010;151:939–947. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Zhang X, Zhou Y, Ansell PJ, Klibanski A. Cyclic AMP stimulates MEG3 gene expression in cells through a cAMP-response element (CRE) in the MEG3 proximal promoter region. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1808–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]