Abstract

The human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) is a member of the lentivirus genus. The virus does not rely exclusively on the host cell machinery, but also on viral proteins that act as molecular switches during the viral life cycle which play significant functions in viral pathogenesis, notably by modulating cell signaling. The role of HIV-1 proteins (Nef, Tat, Vpr, and gp120) in modulating macrophage signaling has been recently unveiled. Accessory, regulatory, and structural HIV-1 proteins interact with signaling pathways in infected macrophages. In addition, exogenous Nef, Tat, Vpr, and gp120 proteins have been detected in the serum of HIV-1 infected patients. Possibly, these proteins are released by infected/apoptotic cells. Exogenous accessory regulatory HIV-1 proteins are able to enter macrophages and modulate cellular machineries including those that affect viral transcription. Furthermore HIV-1 proteins, e.g., gp120, may exert their effects by interacting with cell surface membrane receptors, especially chemokine co-receptors. By activating the signaling pathways such as NF-kappaB, MAP kinase (MAPK) and JAK/STAT, HIV-1 proteins promote viral replication by stimulating transcription from the long terminal repeat (LTR) in infected macrophages; they are also involved in macrophage-mediated bystander T cell apoptosis. The role of HIV-1 proteins in the modulation of macrophage signaling will be discussed in regard to the formation of viral reservoirs and macrophage-mediated T cell apoptosis during HIV-1 infection.

Introduction

HIV-1 infection is characterized by sustained activation of the immune system. As macrophages, along with other cell types, are permissive to HIV-1 infection, they may be infected by the virus, resulting in signaling modulation [1]. Even uninfected macrophages may be activated by the soluble gp120 HIV-1 protein, or gp120 virion, via several signaling pathways. Additionally, soluble HIV-1 proteins such as Nef, Tat, and Vpr have been detected in serum of HIV-1 infected patients, possibly released by infected/apoptotic cells. Soluble exogenous HIV-1 proteins are able to enter macrophages and modulate both cellular machinery and viral transcription. Deciphering the signaling pathways involved in the activation of macrophages in HIV infection is critical to a better understanding of AIDS pathogenesis as this could lead to innovative therapeutic approaches.

HIV-1 Proteins and Macrophage Signaling

Nef

Nef is a 27-kDa myristylated protein which is expressed early in the virus life cycle. Nef down-regulates the cell surface expression of CD4, CD28, and MHC class I [2]. Nef also modulates several signaling pathways [3-8]. While Nef is not considered to be a secreted protein, exogenous Nef has been detected in the sera of AIDS patients and in cultures of HIV-1-infected cells [9]. There is increasing evidence of the ability of extracellular Nef to activate signaling pathways in uninfected cells [9-13]. Indeed, Nef is internalized by MDMs and dendritic cells, but not by T cells [14], when added to cell cultures [14-16]. Recently, Qiao et al. [11] reported that Nef was internalized in B cells in vitro, thereby suppressing CD40-dependent immunoglobulin class switching. The presence of Nef in the sera of HIV-infected patients at concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 ng/mL has also been described [9]. This concentration may be higher in the lymphonodal germinal centers where virion-trapping dendritic cells, as well as virion-infected CD4+ T cells and macrophages, are densely packed [17,18]. Infected cells may release Nef through a non-classical secretory pathway or after lysis. Following this, bystander cells may internalize Nef via endocytosis, pinocytosis or other yet-unknown mechanisms. Regarding intracellular signaling induced by Nef treatment of MDMs, it has been reported that Nef modulates the expression of a significant number of genes as early as 2 hours after treatment [19]. This suggested that a prompt transcriptional cell reprogramming induced by Nef leads to the synthesis and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, which in turn, activate STAT1 and STAT3 signal transducers and transcription activators [20,21]. In line with these results, Nef treatment of MDMs was reported to induce rapid activation of IKK/NF-kB, MAPK and IRF-3 signalling pathways. Nef induces prompt phosphorylation of three MAPKs, i.e., ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 [13,22,23]. A Nef treatment as short as 15 minutes is able to induce p38 phosphorylation, most likely due to rapid recruitment and activation of p38 signaling upstream intermediates. Exogenously added Nef induces rapid phosphorylation of the transcription factor IRF-3, the main regulator of IFN-β gene expression [24-26]. It has also been shown to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT2, well known to be induced by type I IFN signaling, at an early infection stage (8 to 16 h) [22].

Macrophage activation and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by Nef involves NF-κB activation, especially its p50/p50 homodimeric and p65/p50 heterodimeric forms. This event leads to sustained LTR activation [13,19,27]. The activation of NF-κB in macrophages treated with exogenously added Nef occurs as early as 2 hours after treatment [13,28]. NF-κB activation in primary macrophages treated with recombinant Nef is mediated via the canonical pathway, primarily involving IKKβ phosphorylation [28]. Furthermore, many of the transcripts induced in macrophages treated by Nef are encoded by genes regulated by κB-like responsive elements [19] (Figure 1). Therefore, there is evidence that exogenously added Nef plays a critical role in "hijacking" the NF-κB signaling pathway, most likely upstream of IKK, as observed after endogenous expression in macrophages [29]. This observation is in line with the role of Nef-mediated activation of NF-κB, which promotes HIV-1 replication via both direct and cytokine-mediated effects [13]. Thus, in monocyte-derived macrophages, recombinant Nef enhances the production of cytokines such as macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP1α), MIP1β, TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6 involved in the inflammatory response (Figure 1). Additionally, features observed in promonocytic cells and primary macrophages following exposure to recombinant Nef are very similar to those observed following TNFα treatment [30]. Both recombinant Nef and TNFα activate NF-κB, AP-1 and JNK. That recombinant Nef and TNFα activate these signaling pathways suggests the two events might modulate the cellular machinery in a similar way. Therefore, they may have the same effects on HIV-1 replication in mononuclear phagocytes [28]. Exogenous Nef may modulate intracellular signaling pathways downstream of the TNFα receptors (TNFRs), and thus mimic the effects of TNFα on primary macrophages [13].

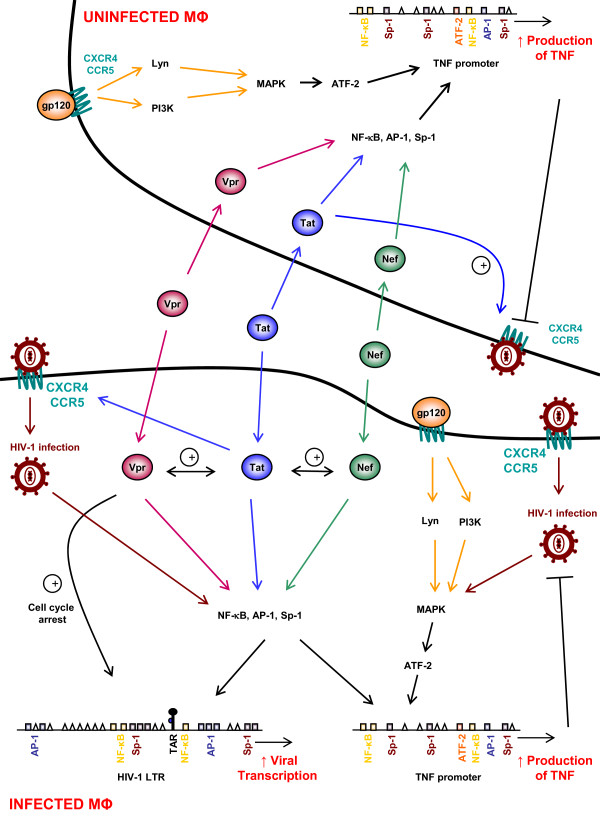

Figure 1.

HIV-1 proteins modulate signaling in the macrophage. The HIV-1 proteins Nef, Tat, Vpr, and gp120 alter cell signaling pathways, both in infected and uninfected macrophages. The presence of exogenous Nef, Tat and Vpr has been reported in sera of AIDS patients, which have the ability to enter the cells. HIV-1 proteins activate multiple transcription factors in macrophages including NF-κB, Sp-1 and AP-1, which have binding sites in the long terminal repeat (LTR) of HIV-1. The induction of these factors results in increased viral production. Furthermore, the activation of these transcription factors enhances cytokine production by macrophages primarily involved in AIDS pathogenesis. TNF promoter is shown as a prototype containing binding sites of NF-κB, Sp-1, and AP-1. Exogenous Nef and Vpr may enhance Tat-mediated transcription in addition to their effect on transcription factors. Moreover, the viral glycoprotein gp120 activates MAPK in uninfected and infected cells, resulting in increased TNFα production through ATF-2 binding sites of its promoter. Tat also stimulates CXCR4/CCR5 surface co-receptor expression, thus enhancing viral entry in cells. Besides LTR activation through transcription factors, Vpr-induced cell cycle arrest facilitates LTR stimulation.

Tat

HIV-1 Tat is a virally encoded transactivating protein which plays a critical role in viral replication and is conserved in genomes of primate lentiviruses [31,32]. Tat is a HIV-1 protein reportedly detected in the sera of infected patients as well as in the media of infected cells [33]. This suggests that it might have a role both as endogenous modulator of cellular functions within infected cells and act on bystander cells. Tat activates monocytes, macrophages, and microglial cells.

Tat Action on monocytes, macrophages, and monocytic cell lines

The HIV-1 Tat protein is essential for efficient transcription of viral genes and for viral replication. It also regulates the expression of several cellular genes and interferes with intracellular signaling [34,35]. The mature protein has a variable size, ranging from 86 to 101 amino acids. It is organized in functional domains required for transactivation activity. The C-terminus contains an RDG motif which mediates cell adhesion and Tat binding to integrin receptors [36]. Specific Tat binding has been reported for at least three cell surface molecules including heparin sulfate, beta-integrin and chemokine receptors. Tat as well as peptides spanning its cysteine-rich region compete with cognate ligands to bind CXCR4, CCR2, and CCR3 chemokine receptors in primary human monocytes and PBMCs. Tat has also been reported to trigger Ca2+ mobilization in macrophages in a concentration-dependent manner through CCR2 and CCR3 [37,38]. Moreover, Tat induces the expression of CCR3, CCR5 and CXCR4 in monocytes/macrophages in a concentration-dependent manner, possibly promoting HIV-1 infection [39]. Finally, Tat has been shown to serve as chemoattractant for monocytes, and pretreatment with Tat enhanced the monocyte invasive properties [40,41].

Functional consequences of Tat activation include TNFα release from macrophages, monocytes and THP-1 monocytic cell lines [42]. Tat-induced TNFα release was dependent on NF-κB activation and mediated through the activation of protein kinase A, phospholipase C (PLC) and protein tyrosine kinase pathways [43]. Transient [Ca2+]i release was observed in macrophages through IP3 receptor-regulated intracellular Ca2+ stores [43]. This Tat-induced [Ca2+]i elevation was not dependent on extracellular Ca2+ or caffeine-sensitive ryanodine receptor-regulated intracellular Ca2+ stores but rather on the PLC, protein kinase C (PKC) and Gi/0 protein pathways. Tat-induced calcium signaling in macrophages leads to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, possibly contributing to inflammation and HIV-1 neuropathogenesis.

Thus, Tat displays biological activities mimicking those mediated by TNFα [28]. HIV-1 Tat may induce the expression of TNFα and various cytokines, including IL-6, TNFβ and TGFβ as well as the expression of cytokine receptors such as the IL-4 receptor [44-49]. Like TNFα, Tat may activate NF-κB, AP-1 and MAPK, including c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK) [50]. Tat activates NF-κB, JNK, and AP-1, but not MEK [50]. These results suggest that HIV-1 Tat and TNFα act through different mechanisms and that HIV-1 Tat does not activate all of the kinases involved in TNFR signaling [51]. In short, like Nef, Tat mimics the effects of TNFα resulting in the enhancement of viral replication via activation of NF-κB, AP-1, JNK, and MAPK.

Action of Tat on microglia

Tat protein is actively produced and released in the central nervous system (CNS) by infected cells [52]. Elevated Tat mRNA levels have been detected in the brain of AIDS patients [53], where Tat is believed to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of HAD through not only its direct neurotoxicity, but also through the release of deleterious products in microglial cells [54]. Although they act as CNS macrophages, microglia cells differ in many aspects from peripheral macrophages. Their morphological and functional specificity responds to cell-cell contacts and secreted factors from surrounding astrocytes and neurons. The strict separation of microglia cells from blood components is due to the blood brain barrier (BBB). This results in a down-regulated "surveillance" phenotype [55]. Microglial cells are nevertheless able to undergo activation and acquire typical macrophage functions such as phagocytosis of microbes or apoptotic bodies and the secretion of inflammatory or anti-inflammatory mediators [56,57].

Tat activates microglia and impairs major molecular mechanisms that normally prevent or shorten microglial activation. As is the case in macrophages, Tat increases microglial production of free radicals as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [42,43,58,59]. Tat induction of NO and inducible NO synthase (iNOS) is enhanced by IFN-γ [60]. This suggests that Tat and IFN-γ cooperatively contribute to the severity of brain damage observed in brain tissues from AIDS patients and animal HAD models.

The transcription factor NF-κB plays a central role in the regulation of inflammatory gene expression and is involved in most Tat-induced effects in microglial cultures [61]. In surveillance microglia, signals provided by astrocytes actively contribute to NF-κB down-modulation [62]. Elevated immunoreactivity for p50/p65 heterodimer subunits was found in microglia and brain macrophages of children with HIV encephalitis [63] despite repression by the surrounding cells. Likewise, nuclear staining for NF-κB in the perivascular microglia/macrophages of deep white matter and basal ganglia correlated with the severity of HIV-associated dementia in AIDS patients [64]. Interestingly, Tat-induced formation of free radicals in microglial cells occurs independently from NF-κB activation [65,66], as lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress still occur in microglial cultures exposed to Tat in the presence of NF-κB inhibitors [65]. Likewise, the pro-oxidant activities of Tat in the N9 microglial cell line depend on MAP kinase activation [66]. Additionally, antioxidants abrogate oxidative stress rather than the other Tat-induced functions such as IL-1β, NO, and TNF-α production or IkBα degradation [65]. Thus, Tat-induced NF-κB activation in microglia may not require the formation of free radicals, although oxidative stress is contributive to its activation [67].

In different cell types, including macrophages and microglia, Tat influences cell function by modifying Ca2+ homeostasis [43]. Indeed, Tat possesses a cysteine-cysteine-phenylalanine domain, enabling Tat to mimic beta chemokine effects on both Ca2+ movements and chemotaxis [38]. In microglia, Ca2+ mobilization and cell migration by Tat are sensitive to pertussis toxin (PTX), but not cholera toxin. This observation supports the involvement of Gi rather than Gs type proteins, as expected for chemokine receptor stimulation [37]. Furthermore, cross-desensitization studies revealed CCR3 receptor involvement. Similar to findings in monocytes, Tat-induced Ca2+ signals in human microglia are characterized by rapid desensitization [68].

Nanomolar concentrations of recombinant Tat have been shown to decrease in a dose- and time-dependent manner, cAMP accumulation induced in microglial cultures by the β-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol, or by forskolin, an activator of adenylyl cyclase [69]. In microglia, increased cAMP accumulation lowers potentially neurotoxic pro-inflammatory molecules [70-76] and promotes the production of neuroprotective or immunosuppressive substances [70]. Thus, Tat may interfere with cAMP's control on microglial activation.

Among the ion channels expressed by microglial cells, there are two major classes of K+-permeable channels: the delayed-outward-rectifying (Kdr) and the inward-rectifying (Kir) channels. Their expression differs in macrophages and microglia. Their expression is finely modulated by both activation and differentiation [77-81]. Chronic microglial cell treatment with high Tat concentration (≥ 100 ng/mL) up-regulates Kdr currents due to NF-κB-dependent increase in channel expression without a significant increase in Kdr currents [82]. Therefore, the hyperpolarization thus induced by Tat may has several consequences. Ca2+ influx depends on a hyperpolarized membrane potential and Tat's β-chemokine mimicry may thus be favored by Kdr currents. Kdr currents may also modulate the microglial respiratory burst and the transport of amino acids through voltage-dependent transporters. The latter is likely to modify the availability of amino acids for protein synthesis [83,84], as well as the dynamics of glutamate exchange between intracellular and extracellular pools. This may affect the regulation of both extracellular glutamate concentration in the vicinity of glutamate-sensitive neurons and glutathione synthesis rate in microglia [85-87].

Vpr

Vpr is a 96 amino acid-long virion-associated protein located in the cytoplasm and nucleus of HIV-infected cells [88-93]. Vpr is not essential for viral replication in T cells, but critical for HIV replication in non-dividing cells such as macrophages [94-99]. Vpr has pleiotropic effects on viral replication, cellular proliferation and differentiation, cytokine production, NF-κB-mediated transcription and apoptosis [100-103].

Vpr has been shown to induce cell cycle arrest at the G2 cell cycle phase [104-107]. G2 cell cycle arrest correlates with the inhibition of Cdc2 activity and parallels enhanced viral replication [108-110]. G2 cell cycle arrest is followed by apoptosis in HIV-infected and Vpr-expressing cells [111]. Apoptosis is mediated through the interaction of Vpr with the mitochondrion permeability transition pore. This interaction opens the pore, causing mitochondrial swelling, release of cytochrome C as well as caspase 9 and caspase 3 activation [111]. p53 tumor suppressor protein may be implicated in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis mediated by Vpr in certain cell types [107].

Vpr transactivates the viral promoter and HIV-1 LTR resulting in increased viral replication. The G2 cell cycle arrest is concomitant with high levels of viral replication in primary human CD4+ T cells. An interaction between Vpr, Sp1 and TFIIB transcription factors is required for Vpr-mediated transcriptional enhancement of HIV-1 LTR [112,113].

Vpr-mediated transactivation necessitates intact NF-κB sites and depends on Vpr's ability to stimulate p300/CBP coactivator function, which promotes cooperative interaction between the RelA subunit of NF-κB and the cyclin B1Cdc2 [114]. A structural and functional interaction between Vpr and Tat has been reported, synergistically enhancing the transcriptional activity of the HIV-1 LTR [114].

The activity of recombinant Vpr (rVpr) in macrophages has been investigated. High concentrations of rVpr as well as the carboxy-terminal Vpr peptide are cytotoxic to macrophages. However, at low concentrations rVpr was shown to enhance the activity of several transcription factors including AP-1, c-Jun, and, NF-κB [115]. Amino- and carboxy-terminal Vpr peptides retained transcription factor activation properties, albeit to a lesser extent than with the full-length rVpr. Similarly to Vpr expressed in infected cells, rVpr stimulated HIV-1 replication in acutely infected primary macrophages. Furthermore, reduced p24 production by macrophages infected with Vpr-deficient virus could be rescued by adding rVpr to culture medium [116]. Exposure to rVpr also increased transcription and p21/waf1 levels in macrophages [117]. These Vpr effects on macrophages may reflect the mechanisms by which Vpr activates the HIV-1 LTR and enhances virus replication in acutely and latently infected cells [88]. Although primarily considered to be a regulator of viral promoter transactivation, transcription factor activation may have significant effects on macrophage cellular functions [117,118]. Additionally, macrophages and PBLs produce less chemokines following recombinant Vpr treatment. This observation suggests that Vpr modulates cytokine production by interfering with NF-κB-mediated transcription [119,120].

gp120

HIV-1 infects human T cells and monocytes/macrophages through the interaction of gp120 with CD4 and the CXCR4 or CCR5 co-receptor, which determines the cellular tropism [121-131]. HIV-1 gp120 down-regulates CD4 expression in primary human macrophages through induction of endogenous TNFα [121,132-136]. Actually, TNFα down-regulates both surface and total CD4 expression in primary human macrophages at the transcription level [134,137-140]. TNFα inhibits R5 and R5/X4 HIV-1 entry into primary macrophages via downregulation of both cell surface CD4 and CCR5 and via enhanced secretion of CC-chemokines, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and RANTES [129,137,141-146]. An iterative pretreatment of primary macrophages with TNFα prior to HIV infection inhibits HIV-1 replication in primary macrophages [142]. The inhibition of HIV-1 entry into primary macrophages following TNFα pretreatment involves TNFR2 and is mediated by the secretion of CC-chemokines such as RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β[140,141]. TNFα induces the production of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β, which in turn down-regulate cell surface CCR5 expression on primary macrophages, resulting in the inhibition of R5 HIV-1 entry [147-151]. In agreement with this observation RANTES inhibits HIV-1 envelope-mediated membrane fusion in primary macrophages [152] and inhibits the activity of the RANTES promoter containing four NF-κB binding sites which is up-regulated by TNFα [153].

Many studies conducted over the past two decades have shown that besides infection, exposure of macrophages to intact virions or soluble gp120 may exert various functional effects on macrophages, including cytokine secretion activation [121,135,154]. However, the specific pathways involved in gp120-induced responses have only been defined recently. The presence of non-infectious virion particles in excess of infectious virus, the ability of gp120 to dissociate from the transmembrane gp41 portion of Env as well as detection of circulating gp120 in infected patients [155] have raised the question of what biological activities this protein is involved in aside from mediating infection. Such studies have demonstrated the ability of gp120 to activate intracellular signaling in multiple cell types as a result of its binding to receptor/co-receptor complex. Although gp120-induced signaling has been extensively investigated in CD4+ T cells, gp120 has also been reported to activate intracellular signals in macrophages [156].

In primary human macrophages, both R5 and X4 gp120 induce calcium mobilization, although R5 gp120 elicited higher peaks and more sustained elevations than X4 gp120 [157,158]. Single-cell patch-clamp recording combined with pharmacological antagonists and current reversal potential analysis identified the ion channels associated with CCR5 and CXCR4 activation: chloride, calcium-activated potassium, and non-selective cation (NSC) channels [157]. These responses to HIV-1 gp120 were mediated by chemokine receptors, but not by CD4, since the responses to R5 Env were absent in macrophages from patients lacking cell surface CCR5 expression (CCR5Δ 32); responses to X4 gp120 were inhibited by a small molecule CXCR4 antagonist [157,159]. While R5 and X4 gp120 generally induced similar signals through CCR5 and CXCR4, respectively, certain differences were noted. R5 Env opened the calcium-activated outward K+ channels more frequently than X4 gp120, and induced Cl- currents of greater amplitude. Gp120, instead of CXCR4 or CCR5 binding chemokines, activated the NSC channel [160].

In addition, gp120 has been shown to activate all three MAPK family members (ERK1/2, JNK, and p38) in macrophages. R5 gp120 triggered macrophage release of MIP-1, MCP-1, and TNFα. The secretion of these products was blocked by small molecule inhibitors of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPKs [39,161].

The src kinases Lyn and Hck are highly expressed in macrophages, and recent in vitro kinase assays demonstrated that R5 gp120 and MIP-1β activated Lyn in macrophages [162]. Neither R5 gp120 nor MIP-1β activated Lyn in macrophages derived from CCR5Δ 32 donors or in cells treated with a small molecule CCR5 inhibitor, indicating that Lyn activation was elicited through CCR5 receptor. Unlike Lyn, Hck activation did not occur in response to gp120 or chemokine stimulation [162,163]. Both a Lyn-specific peptide pseudo-substrate inhibitor and PP2, a broad src family kinase inhibitor, suppressed gp120-induced TNFα production. These results are suggestive of a signaling cascade initiated by gp120 through CCR5, involving Lyn activation of the MAPK pathway, resulting in gp120-induced TNFα release.

Several lines of evidence indicate that HIV-1 gp120/chemokine receptor interactions activate PI3K in macrophages [39,164]. This finding is based upon R5 gp120 activation of protein kinase B (PKB), a downstream target for class I PI3K and a useful indirect indicator of its activation. Furthermore, several small molecule PI3K inhibitors blocked gp120-induced CCR5-mediated ERK1/2 and p38 phosphorylation, as well as TNFα release. These results not only suggest a role for PI3Ks in CCR5 signaling but also indicate that, like Lyn, PI3K acts upstream of MAPKs in the regulation of cytokine production through this pathway [39]. It is unclear which PI3K isoform is involved in these R5 gp120-induced signals, and the relationship between PI3K and Lyn remains to be determined.

Besides chemokine receptors, interactions between HIV-1 gp120 and CD4 stimulate signal transduction pathways, such as activation of PKC, generation of PKC-dependent phosphorylation of CD4, and activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway, which in turn stimulates transcription factors such as NF-kB, AP-1, and Elk-1, as well as induction of cytokine and chemokine gene expression [115,165-172]. Early inflammatory gene products such as TNFα, may stimulate HIV-1 replication in the absence of HIV-1 Tat protein. Thus, the activation of cellular signaling pathways leading to the production of cytokine and chemokine genes by HIV-1 gp120 could facilitate viral replication in the early phases of the viral life cycle [50].

Proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) activation has been suggested as a critical signalling mechanism for integrin-mediated formation of adhesion contacts in macrophages known as podosomes. Pyk2 is known to be activated by chemokines, triggering cell migration [173,174]. CCR5 and CXCR4 are both linked to Pyk2, which is activated by R5 gp120 and MIP-1β as well as X4 gp120 and SDF-1α [161]. Recently, a functional role for Pyk2 in the migration of macrophages has been demonstrated using Pyk2 knockout mice [175], suggesting that gp120 may be involved in macrophage migration.

Macrophage Signaling and HIV-1 Pathogenesis

In this section, we report that several HIV-1 proteins may modulate the macrophage signaling pathway resulting in T lymphocytes depletion and viral cellular reservoir formation, especially in macrophages [176].

Macrophage signaling and T cell apoptosis

Increased spontaneous and activation-induced apoptosis of peripheral CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected patients is observed ex vivo in lymph nodes of HIV-infected patients and of SIV-infected macaques [177-180]. Deciphering the molecular mechanisms involved in CD4+ T cell apoptosis in HIV-infected patients is critical to understanding HIV pathogenesis.

In macrophages, Nef has been shown to activate multiple cellular pathways, possibly leading to increased infection of adjacent T cells through bystander mechanisms involving T cell activation (Figure 2). It has been shown that Nef-expressing macrophages enhance resting CD4+ T cell permissiveness through a complex cellular and soluble interaction involving macrophages, B cells, and CD4+ T cells [29]. Nef expression within macrophages via adenoviral vectors has been shown to induce the secretion of soluble CD23 and ICAM, resulting in up-regulation of costimulatory B cell receptors, including CD22, CD54, CD58, and CD80. This leads to T cell activation upon interaction with B cells via these costimulatory receptors, thus enabling the generation of non-productive or productive reservoirs, depending on the interactions [29].

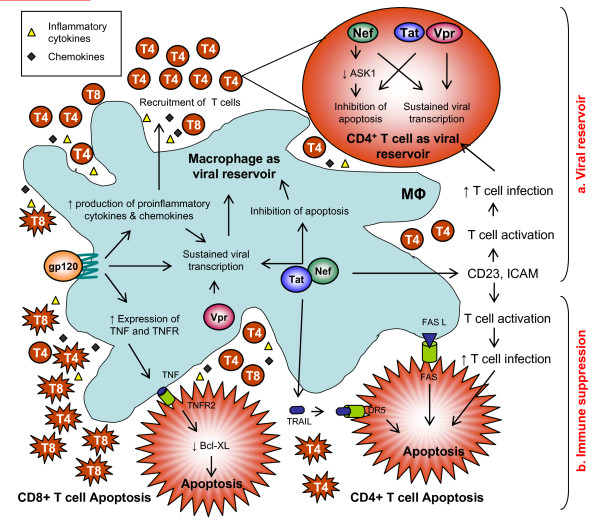

Figure 2.

A model of HIV-1 pathogenesis based on interactions between macrophages and T cells which account for increased immune suppression and cellular virion reservoirs. a) Viral glycoprotein gp120 activates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by macrophages, attracting T cells in the vicinity of macrophages, thereby increasing the number of infected cells and fueling the viral reservoirs. HIV-1 proteins Nef, Tat, and Vpr activate the long terminal repeat (LTR) of HIV-1, resulting in sustained viral growth while also activating anti-apoptotic pathways that favor viral persistence and formation of viral reservoir. b) Viral protein Tat participates in CD4+ T cell death through TRAIL secretion by HIV-1 infected macrophages. Viral gp120 glycoproteins increase the expression of TNF and TNFR on macrophages and T cells, leading to CD8+ T cell apoptosis. Thus, macrophage signaling using viral proteins accounts for both viral persistence and immune suppression during HIV-1 infection.

Furthermore, Nef has been reported to prevent Fas- and TNF-receptor-mediated deaths observed in HIV-infected T cells via interaction with the apoptosis signal regulating kinase-1 (ASK-1). Nef inhibits ASK-1, caspase 3 and caspase 8 activation, resulting in apoptosis blockade in HIV-infected cells [181-184]. Apoptosis was measured in productively infected CD4+ T lymphocytes using a reporter virus and a recombinant HIV infectious clone expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the presence and absence of autologous macrophages. The survival of productively infected CD4+ T lymphocytes has been shown to require Nef expression and activation by TNFα expressed on macrophage surface, thereby participating in the formation and maintenance of viral reservoirs in HIV-infected patients [184].

In addition to the macrophage-mediated formation of T cell reservoirs, in vitro culture models demonstrate that uninfected CD4+ T cells undergo apoptosis upon contact with HIV-infected cells; for example mononuclear phagocytes [180]. Macrophages play a major role in this process, suggesting that apoptosis-inducing ligands expressed by macrophages mediate apoptosis of susceptible CD4+ T cells [159,185-187]. Activated macrophages produce TNFα following HIV infection in vitro [135]. TNFα is released as a soluble factor or expressed on the surface of macrophages under a membrane-bound form that primarily targets TNFR2 rather than TNFR1 [188,189]. TNFR2 stimulation may trigger T cell apoptosis, especially in CD8+ T cells [188]. TNFα and TNF receptors are increased in HIV-infected patients and inversely correlated with CD4+ T cell counts [190]. TNFα is expressed on the surface of activated macrophages, and cell surface TNFR2 is not increased on CD4+ infected T cells. Therefore, for the most part, the apoptosis of CD4+ T lymphocytes is mediated via Fas/Fas ligand interaction [185,186,191]. TNFα causes death at a later stage than Fas and may be transduced through TNFR2, which does not contain homology to the Fas death domain and uses different signaling pathways than TNFR1 [115,185]. Recently, Tat has been reported to induce secretion of soluble TNF-related apoptosis-induced ligand (TRAIL) in human macrophages, leading to the death of bystander CD4+ T lymphocytes [73]. Thus, the production of TRAIL by Tat-stimulated monocytes/macrophages is likely to be an additional mechanism by which HIV-1 infection destroys uninfected bystander cells.

CD8+ T cell apoptosis during HIV infection has been shown to result from the interaction between membrane-bound TNFα expressed on the surface of activated macrophages and TNFR2 expressed on the surface of activated CD8+ T cells [158]. Both membrane-bound TNFα and TNFR2 are up-regulated on macrophages and CD8+ T cells, respectively, following CXCR4 stimulation by HIV gp120. However, CCR5 may also play a role, albeit minor [158]. TNFR2 stimulation of T cells results in decreased intracellular levels of apoptosis protective protein Bcl-XL, a member of the Bcl-2 family [192]. Impaired induction of Bcl-XL has been observed in PBMC isolated from HIV-infected patients [193]. Therefore, TNFR2 stimulation of CD8+ T cells by membrane-bound TNFα expressed on the surface of macrophages might decrease the intracellular levels of anti-apoptotic proteins resulting in CD8+ T cell death.

Additionally, chemokines and activated macrophages have been reported to play a role in HIV-1 gp120-induced neuronal apoptosis [194,195].

Macrophage signaling and formation of viral reservoirs

Whereas CD4+ T cells die within a few days after becoming infected with HIV, infected macrophages seem to persist for months, continuing to release viruses. Several reasons may explain why macrophages are a major cellular reservoir of virions during infection (Figure 2). Macrophages are more resistant than T cells to HIV-induced apoptosis and therefore allow for sustained viral production without fatal cell death. Persistent HIV infection of macrophages results in increased NF-κB levels, involved in the resistance to TNFα-induced apoptosis. Macrophages release CC-chemokines which have the ability to attract CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in their vicinity [196]. They may also block the entry of R5 HIV-1 virions into CD4+ target cells [122]. CC-chemokine production is often associated with that of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα and IL-1β, which stimulate the transcription of HIV LTR via activation of NF-kB [197,198]. Additionally, TNFα may block entry of R5 HIV-1 strains into macrophages via a decreased expression of CCR5 on cell surfaces [137,141,142,147]. Thus, CC-chemokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines facilitate the recruitment and productive infection of CD4+ T lymphocytes via increased viral transcription, while regulating the entry of virions into macrophages, thereby preventing macrophage superinfection. Additionally, apoptosis inhibition in HIV-1 infected T cells enhances virus production and facilitates persistent infection [199]. HIV-1 proteins, by modulation of the TNFR signaling pathway, lead to the formation of viral reservoirs, especially in primary macrophages [50]. Altogether, the data indicate that both viral and cellular factors are involved in the controlled and sustained production of virions in infected CD4+ T lymphocytes and macrophages, thereby expanding the viral reservoir which fuels disease progression.

Conclusion

The macrophage is essential in the loss of T lymphocytes and formation of viral reservoirs; it plays a critical role in HIV-1 disease progression. Several HIV-1 proteins modulate signaling in infected and bystander macrophages, thereby facilitating disease progression. A better understanding of the manner by which HIV-1 modulates signaling in macrophages may be instrumental in the development of new therapeutic approaches that may ultimately restrict or decrease the size of cellular virion reservoirs in HIV-1-infected patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GH was responsible for drafting and revising the manuscript as well as organizing the content. GG was responsible for drafting and revising the section "Action of Tat on microglia". KAK created Figures 1 and 2. WA assisted in revising the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Georges Herbein, Email: georges.herbein@univ-fcomte.fr.

Gabriel Gras, Email: gabriel.gras@cea.fr.

Kashif Aziz Khan, Email: kashif_aziz_khan@yahoo.com.

Wasim Abbas, Email: wazim_cemb@hotmail.com.

Acknowledgements

This review is the result of a reflection conducted by the Association for Macrophages and Infection Research (AMIR). The work of G. Herbein, W. Abbas, and K.A. Khan was supported by institutional funding from Franche-Comté University. W. Abbas and K.A. Khan are supported by grants of the Higher Education Committee of Pakistan. The group led by G. Gras was supported by grants from the Agence nationale de recherche sur le sida et les hépatites virales, the Fondation pour la recherche médicale and Ensemble contre le sida (Sidaction).

References

- Coleman CM, Wu L. HIV interactions with monocytes and dendritic cells: viral latency and reservoirs. Retrovirology. 2009;6:51. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JL, Garcia JV. HIV-1 Nef: at the crossroads. Retrovirology. 2008;5:84. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken C, Trono D. Nef stimulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA synthesis. J Virol. 1995;69:5048–5056. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5048-5056.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan JF, Bacon KB, Hardiman G, Wang W, Soo K, Rossi D, Greaves DR, Zlotnik A, Schall TJ. A new class of membrane-bound chemokine with a CX3C motif. Nature. 1997;385:640–644. doi: 10.1038/385640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M, Keshav S, Harris N, Gordon S. Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 1992;176:287–292. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MD, Warmerdam MT, Gaston I, Greene WC, Feinberg MB. The human immunodeficiency virus-1 nef gene product: a positive factor for viral infection and replication in primary lymphocytes and macrophages. J Exp Med. 1994;179:101–113. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lama J, Mangasarian A, Trono D. Cell-surface expression of CD4 reduces HIV-1 infectivity by blocking Env incorporation in a Nef- and Vpu-inhibitable manner. Curr Biol. 1999;9:622–631. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80284-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz O, Marechal V, Le Gall S, Lemonnier F, Heard JM. Endocytosis of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules is induced by the HIV-1 Nef protein. Nat Med. 1996;2:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii Y, Otake K, Tashiro M, Adachi A. Soluble Nef antigen of HIV-1 is cytotoxic for human CD4+ T cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;393:93–96. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00859-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigino E, Haraguchi S, Koutsonikolis A, Cianciolo GJ, Owens U, Good RA, Day NK. Interleukin 10 is induced by recombinant HIV-1 Nef protein involving the calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphodiesterase signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3178–3182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao X, He B, Chiu A, Knowles DM, Chadburn A, Cerutti A. Human immunodeficiency virus 1 Nef suppresses CD40-dependent immunoglobulin class switching in bystander B cells. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:302–310. doi: 10.1038/ni1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobiume M, Fujinaga K, Suzuki S, Komoto S, Mukai T, Ikuta K. Extracellular Nef protein activates signal transduction pathway from Ras to mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades that leads to activation of human immunodeficiency virus from latency. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2002;18:461–467. doi: 10.1089/088922202753614227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varin A, Manna SK, Quivy V, Decrion AZ, Van Lint C, Herbein G, Aggarwal BB. Exogenous Nef protein activates NF-kappa B, AP-1, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase and stimulates HIV transcription in promonocytic cells. Role in AIDS pathogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2219–2227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandrini L, Santarcangelo AC, Olivetta E, Ferrantelli F, d'Aloja P, Pugliese K, Pelosi E, Chelucci C, Mattia G, Peschle C, Verani P, Federico M. T-tropic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 Nef protein enters human monocyte-macrophages and induces resistance to HIV replication: a possible mechanism of HIV T-tropic emergence in AIDS. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:2905–2917. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-12-2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta MG, Camponeschi B, Straface E, Malorni W, Viora M. Induction of interleukin-15 production by HIV-1 nef protein: a role in the proliferation of uninfected cells. Exp Cell Res. 1999;250:112–121. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta MG, Mattioli B, Spadaro F, Straface E, Giordani L, Ramoni C, Malorni W, Viora M. HIV-1 Nef triggers Vav-mediated signaling pathway leading to functional and morphological differentiation of dendritic cells. FASEB J. 2003;17:2025–2036. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0272com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuster H, Opravil M, Ott P, Schlaepfer E, Fischer M, Gunthard HF, Luthy R, Weber R, Cone RW. Treatment-induced decline of human immunodeficiency virus-1 p24 and HIV-1 RNA in lymphoid tissue of patients with early human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1973–1986. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65070-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soudeyns H, Rebai N, Pantaleo GP, Ciurli C, Boghossian T, Sekaly RP, Fauci AS. The T cell receptor V beta repertoire in HIV-1 infection and disease. Semin Immunol. 1993;5:175–185. doi: 10.1006/smim.1993.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivetta E, Percario Z, Fiorucci G, Mattia G, Schiavoni I, Dennis C, Jager J, Harris M, Romeo G, Affabris E, Federico M. HIV-1 Nef induces the release of inflammatory factors from human monocyte/macrophages: involvement of Nef endocytotic signals and NF-kappa B activation. J Immunol. 2003;170:1716–1727. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federico M, Percario Z, Olivetta E, Fiorucci G, Muratori C, Micheli A, Romeo G, Affabris E. HIV-1 Nef activates STAT1 in human monocytes/macrophages through the release of soluble factors. Blood. 2001;98:2752–2761. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.9.2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percario Z, Olivetta E, Fiorucci G, Mangino G, Peretti S, Romeo G, Affabris E, Federico M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Nef activates STAT3 in primary human monocyte/macrophages through the release of soluble factors: involvement of Nef domains interacting with the cell endocytotic machinery. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:821–832. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0403161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangino G, Percario ZA, Fiorucci G, Vaccari G, Manrique S, Romeo G, Federico M, Geyer M, Affabris E. In vitro treatment of human monocytes/macrophages with myristoylated recombinant Nef of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 leads to the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases, IkappaB kinases, and interferon regulatory factor 3 and to the release of beta interferon. J Virol. 2007;81:2777–2791. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01640-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrager JA, Der Minassian V, Marsh JW. HIV Nef increases T cell ERK MAP kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6137–6142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscott J, Pitha P, Genin P, Nguyen H, Heylbroeck C, Mamane Y, Algarte M, Lin R. Triggering the interferon response: the role of IRF-3 transcription factor. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1999;19:1–13. doi: 10.1089/107999099314360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Tanaka N, Hata N, Oda E, Taniguchi T. Involvement of the IRF family transcription factor IRF-3 in virus-induced activation of the IFN-beta gene. FEBS Lett. 1998;425:112–116. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama M, Suhara W, Fukuhara Y, Fukuda M, Nishida E, Fujita T. Direct triggering of the type I interferon system by virus infection: activation of a transcription factor complex containing IRF-3 and CBP/p300. EMBO J. 1998;17:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilareski EM, Shah S, Nonnemacher MR, Wigdahl B. Regulation of HIV-1 transcription in cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage. Retrovirology. 2009;6:118. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbein G, Varin A, Larbi A, Fortin C, Mahlknecht U, Fulop T, Aggarwal BB. Nef and TNFalpha are coplayers that favor HIV-1 replication in monocytic cells and primary macrophages. Curr HIV Res. 2008;6:117–129. doi: 10.2174/157016208783884985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swingler S, Brichacek B, Jacque JM, Ulich C, Zhou J, Stevenson M. HIV-1 Nef intersects the macrophage CD40L signalling pathway to promote resting-cell infection. Nature. 2003;424:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nature01749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlknecht U, Will J, Varin A, Hoelzer D, Herbein G. Histone deacetylase 3, a class I histone deacetylase, suppresses MAPK11-mediated activating transcription factor-2 activation and represses TNF gene expression. J Immunol. 2004;173:3979–3990. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KA. Tat and the HIV-1 promoter. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:461–468. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90012-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeang KT, Xiao H, Rich EA. Multifaceted activities of the HIV-1 transactivator of transcription, Tat. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28837–28840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.28837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensoli B, Buonaguro L, Barillari G, Fiorelli V, Gendelman R, Morgan RA, Wingfield P, Gallo RC. Release, uptake, and effects of extracellular human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein on cell growth and viral transactivation. J Virol. 1993;67:277–287. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.277-287.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan D, Albini A. From the outside in: extracellular activities of HIV Tat. Adv Pharmacol. 2000;48:229–250. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(00)48008-7. full_text. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier VW, Gu L, O'Donoghue N, Pennington S, Sheehy N, Hall WW. In vitro nuclear interactome of the HIV-1 Tat protein. Retrovirology. 2009;6:47. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HK, Gallo RC, Ensoli B. Regulation of Cellular Gene Expression and Function by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Tat Protein. J Biomed Sci. 1995;2:189–202. doi: 10.1007/BF02253380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albini A, Benelli R, Giunciuglio D, Cai T, Mariani G, Ferrini S, Noonan DM. Identification of a novel domain of HIV tat involved in monocyte chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15895–15900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.15895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Neuveut C, Tiffany HL, Benkirane M, Rich EA, Murphy PM, Jeang KT. Selective CXCR4 antagonism by Tat: implications for in vivo expansion of coreceptor use by HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11466–11471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona AE, Pioro EP, Sasse ME, Kostenko V, Cardona SM, Dijkstra IM, Huang D, Kidd G, Dombrowski S, Dutta R, Lee JC, Cook DN, Jung S, Lira SA, Littman DR, Ransohoff RM. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:917–924. doi: 10.1038/nn1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafrenie RM, Wahl LM, Epstein JS, Hewlett IK, Yamada KM, Dhawan S. HIV-1-Tat modulates the function of monocytes and alters their interactions with microvessel endothelial cells. A mechanism of HIV pathogenesis. J Immunol. 1996;156:1638–1645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafrenie RM, Wahl LM, Epstein JS, Hewlett IK, Yamada KM, Dhawan S. HIV-1-Tat protein promotes chemotaxis and invasive behavior by monocytes. J Immunol. 1996;157:974–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science. 2005;308:1314–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power C, McArthur JC, Nath A, Wehrly K, Mayne M, Nishio J, Langelier T, Johnson RT, Chesebro B. Neuronal death induced by brain-derived human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope genes differs between demented and nondemented AIDS patients. J Virol. 1998;72:9045–9053. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9045-9053.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri RK, Aggarwal BB. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat gene up-regulates interleukin 4 receptors on a human B-lymphoblastoid cell line. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3787–3790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautonen J, Rautonen N, Martin NL, Wara DW. HIV type 1 Tat protein induces immunoglobulin and interleukin 6 synthesis by uninfected peripheral blood mononuclear cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:781–785. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry KJ, Reddy HR, Pandita R, Totpal K, Aggarwal BB. HIV-1 tat gene induces tumor necrosis factor-beta (lymphotoxin) in a human B-lymphoblastoid cell line. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20091–20093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri RK, Leland P, Aggarwal BB. Constitutive expression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat gene inhibits interleukin 2 and interleukin 2 receptor expression in a human CD4+ T lymphoid (H9) cell line. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:31–40. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain SR, Leland P, Aggarwal BB, Puri RK. Transcriptional up-regulation of interleukin 4 receptors by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat gene. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:1349–1359. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz M, Clark-Lewis I, Ganu V. HIV-1 transactivator protein Tat induces proliferation and TGF beta expression in human articular chondrocytes. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:365–371. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbein G, Khan KA. Is HIV infection a TNF receptor signalling-driven disease? Trends Immunol. 2008;29:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Manna SK, Dhawan S, Aggarwal BB. HIV-Tat protein activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase and activator protein-1. J Immunol. 1998;161:776–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensoli B, Buonaguro L, Barillari G, Fiorelli V, Gendelman R, Morgan RA, Wingfield P, Gallo RC. Release, uptake, and effects of extracellular human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein on cell growth and viral transactivation. J Virol. 1993;67:277–287. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.277-287.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath A, Geiger J. Neurobiological aspects of human immunodeficiency virus infection: neurotoxic mechanisms. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;54:19–33. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(97)00053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghafouri M, Amini S, Khalili K, Sawaya BE. HIV-1 associated dementia: symptoms and causes. Retrovirology. 2006;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial physiology: unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:119–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minghetti L, Levi G. Microglia as effector cells in brain damage and repair: focus on prostanoids and nitric oxide. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;54:99–125. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(97)00052-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit WJ. Microglia and the response to brain injury. Ernst Schering Res Found Workshop. 2002. pp. 11–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheng WS, Hu S, Hegg CC, Thayer SA, Peterson PK. Activation of human microglial cells by HIV-1 gp41 and Tat proteins. Clin Immunol. 2000;96:243–251. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya BE, Thatikunta P, Denisova L, Brady J, Khalili K, Amini S. Regulation of TNFalpha and TGFbeta-1 gene transcription by HIV-1 Tat in CNS cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;87:33–42. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(98)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polazzi E, Levi G, Minghetti L. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein stimulates inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide production in microglial cultures. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:825–831. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199908000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Simone R, Ajmone-Cat MA, Minghetti L. Atypical antiinflammatory activation of microglia induced by apoptotic neurons: possible role of phosphatidylserine-phosphatidylserine receptor interaction. Mol Neurobiol. 2004;29:197–212. doi: 10.1385/MN:29:2:197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstiel P, Lucius R, Deuschl G, Sievers J, Wilms H. From theory to therapy: implications from an in vitro model of ramified microglia. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;54:18–25. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollard SC, James HJ, Sharer LR, Epstein LG, Gelbard HA, Dewhurst S. Activation of nuclear factor kappa B in brains from children with HIV-1 encephalitis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1995;21:518–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1995.tb01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostasy K, Monti L, Yiannoutsos C, Wu J, Bell J, Hedreen J, Navia BA. NFkappaB activation, TNF-alpha expression, and apoptosis in the AIDS-Dementia-Complex. J Neurovirol. 2000;6:537–543. doi: 10.3109/13550280009091954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini A, Ajmone-Cat MA, Bernardo A, Levi G, Minghetti L. Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 Tat protein induces nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB activation and oxidative stress in microglial cultures by independent mechanisms. J Neurochem. 2001;79:713–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller AJ, Barger SW, Moss NI, Pham JT, Keller JN, Nath A. Pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant properties of the HIV protein Tat in a microglial cell line: attenuation by 17 beta-estradiol. J Neurochem. 2001;78:1315–1324. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie A, O'Neill LA. Oxidative stress and nuclear factor-kappaB activation: a reassessment of the evidence in the light of recent discoveries. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:13–23. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegg CC, Hu S, Peterson PK, Thayer SA. Beta-chemokines and human immunodeficiency virus type-1 proteins evoke intracellular calcium increases in human microglia. Neuroscience. 2000;98:191–199. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrizio M, Colucci M, Levi G. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein decreases cyclic AMP synthesis in rat microglia cultures. J Neurochem. 2001;77:399–407. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi F, De Simone R, Columba-Cabezas S, Levi G. Opposite effects of interferon-gamma and prostaglandin E2 on tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-10 production in microglia: a regulatory loop controlling microglia pro- and anti-inflammatory activities. J Neurosci Res. 1999;56:571–580. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990615)56:6<571::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi F, Penna G, Cerase J, Menendez Iglesias B, Adorini L. IL-12 production by central nervous system microglia is inhibited by astrocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:1604–1612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano AO, Kraig RP. Prostaglandin E receptor subtypes in cultured rat microglia and their role in reducing lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-1beta production. J Neurochem. 1999;72:565–575. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos D, Grutzendler J, Yang G, Kim JV, Zuo Y, Jung S, Littman DR, Dustin ML, Gan WB. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:752–758. doi: 10.1038/nn1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minghetti L, Nicolini A, Polazzi E, Creminon C, Maclouf J, Levi G. Prostaglandin E2 downregulates inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in microglia by increasing cAMP levels. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;433:181–184. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1810-9_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minghetti L, Nicolini A, Polazzi E, Creminon C, Maclouf J, Levi G. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in activated rat microglial cultures is downregulated by exogenous prostaglandin E2 and by cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Glia. 1997;19:152–160. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199702)19:2<152::AID-GLIA6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Prinz M, Stagi M, Chechneva O, Neumann H. TREM2-transduced myeloid precursors mediate nervous tissue debris clearance and facilitate recovery in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr B, Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettenmann H, Hoppe D, Gottmann K, Banati R, Kreutzberg G. Cultured microglial cells have a distinct pattern of membrane channels different from peritoneal macrophages. J Neurosci Res. 1990;26:278–287. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490260303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotzer AR, Cotman CW. Voltage-gated currents expressed by rat microglia in culture. Glia. 1992;6:81–88. doi: 10.1002/glia.440060202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visentin S, Agresti C, Patrizio M, Levi G. Ion channels in rat microglia and their different sensitivity to lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma. J Neurosci Res. 1995;42:439–451. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490420402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone C, Le Pavec G, Meme W, Porcheray F, Samah B, Dormont D, Gras G. Characterization of human monocyte-derived microglia-like cells. Glia. 2006;54:183–192. doi: 10.1002/glia.20372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visentin S, Levi G. Protein kinase C involvement in the resting and interferon-gamma-induced K+ channel profile of microglial cells. J Neurosci Res. 1997;47:233–241. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19970201)47:3<233::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visentin S, Renzi M, Levi G. Altered outward-rectifying K(+) current reveals microglial activation induced by HIV-1 Tat protein. Glia. 2001;33:181–190. doi: 10.1002/1098-1136(200103)33:3<181::AID-GLIA1017>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman CI. Molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of amino acid transport. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1991;55:71–84. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(91)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gras G, Porcheray F, Samah B, Leone C. The glutamate-glutamine cycle as an inducible, protective face of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1067–1075. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcheray F, Leone C, Samah B, Rimaniol AC, Dereuddre-Bosquet N, Gras G. Glutamate metabolism in HIV-infected macrophages: implications for the CNS. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C618–626. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00021.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimaniol AC, Mialocq P, Clayette P, Dormont D, Gras G. Role of glutamate transporters in the regulation of glutathione levels in human macrophages. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1964–1970. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur JC, Hoover DR, Bacellar H, Miller EN, Cohen BA, Becker JT, Graham NM, McArthur JH, Selnes OA, Jacobson LP. Dementia in AIDS patients: incidence and risk factors. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Neurology. 1993;43:2245–2252. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerman M. HIV-1, Vpr and the cell cycle. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00676-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway GP, Martin SR, Huang Y, Nagashima KA, Cayanan C, Maddon PJ, Koup RA, Moore JP, Paxton WA. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbramanian RA, Kessous-Elbaz A, Lodge R, Forget J, Yao XJ, Bergeron D, Cohen EA. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr is a positive regulator of viral transcription and infectivity in primary human macrophages. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1103–1111. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodicka MA, Koepp DM, Silver PA, Emerman M. HIV-1 Vpr interacts with the nuclear transport pathway to promote macrophage infection. Genes Dev. 1998;12:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquot G, Le Rouzic E, David A, Mazzolini J, Bouchet J, Bouaziz S, Niedergang F, Pancino G, Benichou S. Localization of HIV-1 Vpr to the nuclear envelope: impact on Vpr functions and virus replication in macrophages. Retrovirology. 2007;4:84. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzinger NK, Bukinsky MI, Haggerty SA, Ragland AM, Kewalramani V, Lee MA, Gendelman HE, Ratner L, Stevenson M, Emerman M. The Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 influences nuclear localization of viral nucleic acids in nondividing host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7311–7315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Shibata R, Kiyomasu T, Higuchi I, Kishida Y, Ishimoto A, Adachi A. Mutational analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus vpr open reading frame. J Virol. 1989;63:4110–4114. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.4110-4114.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westervelt P, Henkel T, Trowbridge DB, Orenstein J, Heuser J, Gendelman HE, Ratner L. Dual regulation of silent and productive infection in monocytes by distinct human immunodeficiency virus type 1 determinants. J Virol. 1992;66:3925–3931. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3925-3931.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balotta C, Lusso P, Crowley R, Gallo RC, Franchini G. Antisense phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides targeted to the vpr gene inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in primary human macrophages. J Virol. 1993;67:4409–4414. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4409-4414.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balliet JW, Kolson DL, Eiger G, Kim FM, McGann KA, Srinivasan A, Collman R. Distinct effects in primary macrophages and lymphocytes of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 accessory genes vpr, vpu, and nef: mutational analysis of a primary HIV-1 isolate. Virology. 1994;200:623–631. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albright AV, Shieh JT, Itoh T, Lee B, Pleasure D, O'Connor MJ, Doms RW, Gonzalez-Scarano F. Microglia express CCR5, CXCR4, and CCR3, but of these, CCR5 is the principal coreceptor for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 dementia isolates. J Virol. 1999;73:205–213. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.205-213.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerman M, Malim MH. HIV-1 regulatory/accessory genes: keys to unraveling viral and host cell biology. Science. 1998;280:1880–1884. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel AD, Young JA. HIV-1: fifteen proteins and an RNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukrinsky M, Adzhubei A. Viral protein R of HIV-1. Rev Med Virol. 1999;9:39–49. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1654(199901/03)9:1<39::AID-RMV235>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SA, Poon B, Song JY, Chen IS. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr induces apoptosis through caspase activation. J Virol. 2000;74:3105–3111. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.7.3105-3111.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Choe S, Walker R, Di Marzio P, Morgan DO, Landau NR. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J Virol. 1995;69:6705–6711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6705-6711.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jowett JB, Planelles V, Poon B, Shah NP, Chen ML, Chen IS. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr gene arrests infected T cells in the G2 + M phase of the cell cycle. J Virol. 1995;69:6304–6313. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6304-6313.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re F, Braaten D, Franke EK, Luban J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr arrests the cell cycle in G2 by inhibiting the activation of p34cdc2-cyclin B. J Virol. 1995;69:6859–6864. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6859-6864.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya BE, Khalili K, Mercer WE, Denisova L, Amini S. Cooperative actions of HIV-1 Vpr and p53 modulate viral gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20052–20057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartz SR, Rogel ME, Emerman M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cell cycle control: Vpr is cytostatic and mediates G2 accumulation by a mechanism which differs from DNA damage checkpoint control. J Virol. 1996;70:2324–2331. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2324-2331.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao XJ, Mouland AJ, Subbramanian RA, Forget J, Rougeau N, Bergeron D, Cohen EA. Vpr stimulates viral expression and induces cell killing in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected dividing Jurkat T cells. J Virol. 1998;72:4686–4693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4686-4693.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Yamaguchi T, Akimoto Y, Rattner JB, Hirano H, Nakauchi H. Induction of M-phase arrest and apoptosis after HIV-1 Vpr expression through uncoupling of nuclear and centrosomal cycle in HeLa cells. Exp Cell Res. 2000;258:261–269. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacotot E, Ferri KF, El Hamel C, Brenner C, Druillennec S, Hoebeke J, Rustin P, Metivier D, Lenoir C, Geuskens M, Vieira HL, Loeffler M, Belzacq AS, Briand JP, Zamzami N, Edelman L, Xie ZH, Reed JC, Roques BP, Kroemer G. Control of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization by adenine nucleotide translocator interacting with HIV-1 viral protein rR and Bcl-2. J Exp Med. 2001;193:509–519. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.4.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummuluru S, Emerman M. Cell cycle- and Vpr-mediated regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression in primary and transformed T-cell lines. J Virol. 1999;73:5422–5430. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5422-5430.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Mukherjee S, Jia F, Narayan O, Zhao LJ. Interaction of virion protein Vpr of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with cellular transcription factor Sp1 and trans-activation of viral long terminal repeat. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25564–25569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya BE, Khalili K, Gordon J, Taube R, Amini S. Cooperative interaction between HIV-1 regulatory proteins Tat and Vpr modulates transcription of the viral genome. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35209–35214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varin A, Decrion AZ, Sabbah E, Quivy V, Sire J, Van Lint C, Roques BP, Aggarwal BB, Herbein G. Synthetic Vpr protein activates activator protein-1, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and NF-kappaB and stimulates HIV-1 transcription in promonocytic cells and primary macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42557–42567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502211200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein DA, Sherman MP, Penn ML, Chin PS, De Noronha CM, Greene WC, Goldsmith MA. HIV-1 Vpr enhances viral burden by facilitating infection of tissue macrophages but not nondividing CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1407–1419. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez N, Greenwell-Wild T, Marinos NJ, Swaim WD, Nares S, Ott DE, Schubert U, Henklein P, Orenstein JM, Sporn MB, Wahl SM. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-induced macrophage gene expression includes the p21 gene, a target for viral regulation. J Virol. 2005;79:4479–4491. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4479-4491.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthumani K, Hwang DS, Choo AY, Mayilvahanan S, Dayes NS, Thieu KP, Weiner DB. HIV-1 Vpr inhibits the maturation and activation of macrophages and dendritic cells in vitro. Int Immunol. 2005;17:103–116. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthumani K, Kudchodkar S, Papasavvas E, Montaner LJ, Weiner DB, Ayyavoo V. HIV-1 Vpr regulates expression of beta chemokines in human primary lymphocytes and macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:366–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthumani K, Hwang DS, Dayes NS, Kim JJ, Weiner DB. The HIV-1 accessory gene vpr can inhibit antigen-specific immune function. DNA Cell Biol. 2002;21:689–695. doi: 10.1089/104454902760330237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbein G, Keshav S, Collin M, Montaner LJ, Gordon S. HIV-1 induces tumour necrosis factor and IL-1 gene expression in primary human macrophages independent of productive infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;95:442–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb07016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocchi F, DeVico AL, Garzino-Demo A, Arya SK, Gallo RC, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1 alpha, and MIP-1 beta as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder CC, Feng Y, Kennedy PE, Murphy PM, Berger EA. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath PD, Wu L, Mackay CR, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton RE, Hill CM, Davis CB, Peiper SC, Schall TJ, Littman DR, Landau NR. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Hao W, Letiembre M, Walter S, Kulanga M, Neumann H, Fassbender K. Suppression of microglial inflammatory activity by myelin phagocytosis: role of p47-PHOX-mediated generation of reactive oxygen species. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12904–12913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2531-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doranz BJ, Rucker J, Yi Y, Smyth RJ, Samson M, Peiper SC, Parmentier M, Collman RG, Doms RW. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the beta-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtmayerova H, Sherry B, Bukrinsky M. Chemokines and HIV replication. Nature. 1996;382:767. doi: 10.1038/382767a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Roderiquez G, Oravecz T, Norcross MA. Cytokine regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry and replication in human monocytes/macrophages through modulation of CCR5 expression. J Virol. 1998;72:7642–7647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7642-7647.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verani A, Gras G, Pancino G. Macrophages and HIV-1: dangerous liaisons. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:195–212. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melikyan GB. Common principles and intermediates of viral protein-mediated fusion: the HIV-1 paradigm. Retrovirology. 2008;5:111. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamini A, Faggioli E, Bolacchi F, Gessani S, Cappannoli L, Uccella I, Demin F, Capozzi M, Cicconi R, Placido R, Vendetti S, Colizzi GM, Rocchi G. Enhanced production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 due to prolonged response to lipopolysaccharide in human macrophages infected in vitro with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:832–842. doi: 10.1086/314662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse KA, Cosentino LM, Weih KA, Pyle SW, Robbins PB, Hochstein HD, Natarajan V, Farrar WL. The HIV-1 gp120 envelope protein has the intrinsic capacity to stimulate monokine secretion. J Immunol. 1991;147:2892–2901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsten V, Gordon S, Kirn A, Herbein G. HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 down-regulates CD4 expression in primary human macrophages through induction of endogenous tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Immunology. 1996;88:55–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Koyanagi Y, Chen IS. Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha can be induced from mononuclear phagocytes by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 binding to the CD4 receptor. J Virol. 1989;63:4404–4408. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4404-4408.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe W, Volsky DJ, Potash MJ. Induction of rapid and extensive beta-chemokine synthesis in macrophages by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and gp120, independently of their coreceptor phenotype. J Virol. 2001;75:10738–10745. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10738-10745.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailer RT, Lee B, Montaner LJ. IL-13 and TNF-alpha inhibit dual-tropic HIV-1 in primary macrophages by reduction of surface expression of CD4, chemokine receptors CCR5, CXCR4 and post-entry viral gene expression. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1340–1349. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(200005)30:5<1340::AID-IMMU1340>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faltynek CR, Finch LR, Miller P, Overton WR. Treatment with recombinant IFN-gamma decreases cell surface CD4 levels on peripheral blood monocytes and on myelomonocyte cell lines. J Immunol. 1989;142:500–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner LJ, Herbein G, Gordon S. Regulation of macrophage activation and HIV replication. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;374:47–56. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1995-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter RL, Zheng J, Che M, Niemann D, Liu Y, He J, Thomas E, Gendelman HE. Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection, beta-chemokine production, and CCR5 expression in CD40L-stimulated macrophages: immune control of viral entry. J Virol. 2001;75:4308–4320. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4308-4320.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbein G, Montaner LJ, Gordon S. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibits entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 into primary human macrophages: a selective role for the 75-kilodalton receptor. J Virol. 1996;70:7388–7397. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7388-7397.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbein G, Gordon S. 55- and 75-kilodalton tumor necrosis factor receptors mediate distinct actions in regard to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in primary human macrophages. J Virol. 1997;71:4150–4156. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.4150-4156.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan PR, Guatelli JC, Munis JR, Richman DD, Kornbluth RS. Mechanisms for the inhibition of HIV replication by interferons-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in primary human macrophages. Virology. 1993;193:138–148. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitseva M, Lee S, Lapham C, Taffs R, King L, Romantseva T, Manischewitz J, Golding H. Interferon gamma and interleukin 6 modulate the susceptibility of macrophages to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Blood. 2000;96:3109–3117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer I, Vieillard V, De Maeyer E. Retrovirally mediated IFN-beta transduction of macrophages induces resistance to HIV, correlated with up-regulation of RANTES production and down-regulation of C-C chemokine receptor-5 expression. J Immunol. 2000;164:1582–1587. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewson TJ, Logie JJ, Simmonds P, Howie SE. A CCR5-dependent novel mechanism for type 1 HIV gp120 induced loss of macrophage cell surface CD4. J Immunol. 2001;166:4835–4842. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.4835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane BR, Markovitz DM, Woodford NL, Rochford R, Strieter RM, Coffey MJ. TNF-alpha inhibits HIV-1 replication in peripheral blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages by inducing the production of RANTES and decreasing C-C chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) expression. J Immunol. 1999;163:3653–3661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey MJ, Woffendin C, Phare SM, Strieter RM, Markovitz DM. RANTES inhibits HIV-1 replication in human peripheral blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L1025–1029. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.5.L1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Jolly PE. Effect of beta-chemokines on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication, binding, uncoating, and CCR5 receptor expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Hum Virol. 1999;2:123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capobianchi MR, Abbate I, Antonelli G, Turriziani O, Dolei A, Dianzani F. Inhibition of HIV type 1 BaL replication by MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta, and RANTES in macrophages. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:233–240. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylisastigui L, Amzazi S, Bakri Y, Vizzavona J, Vita C, Gluckman JC, Benjouad A. Effect of RANTES on the infection of monocyte-derived primary macrophages by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and type 2. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 1998;52:447–453. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(99)80023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stantchev TS, Broder CC. Consistent and significant inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope-mediated membrane fusion by beta-chemokines (RANTES) in primary human macrophages. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:68–78. doi: 10.1086/315700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriuchi H, Moriuchi M, Fauci AS. Nuclear factor-kappa B potently up-regulates the promoter activity of RANTES, a chemokine that blocks HIV infection. J Immunol. 1997;158:3483–3491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl LM, Corcoran ML, Pyle SW, Arthur LO, Harel-Bellan A, Farrar WL. Human immunodeficiency virus glycoprotein (gp120) induction of monocyte arachidonic acid metabolites and interleukin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:621–625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]