Abstract

Protein folding is a prominent chaperone function of the Hsp70 system. Refolding of an unfolded protein is efficiently mediated by the Hsc70 system with either type 1 DnaJ protein, DjA1 or DjA2, and a nucleotide exchange factor. A surface plasmon resonance technique was applied to investigate substrate recognition by the Hsc70 system and demonstrated that multiple Hsc70 proteins and a dimer of DjA1 initially bind independently to an unfolded protein. The association rate of the Hsc70 was faster than that of DjA1 under folding-compatible conditions. The Hsc70 binding involved a conformational change, whereas the DjA1 binding was bivalent and substoichiometric. Consistently, we found that the bound 14C-labeled Hsc70 to the unfolded protein became more resistant to tryptic digestion. The gel filtration and cross-linking experiments revealed the predominant presence of the DjA1 dimer. Furthermore, the Hsc70 and DjA1 bound to distinct sets of peptide array sequences. All of these findings argue against the generality of the widely proposed hypothesis that the DnaJ-bound substrate is targeted and transferred to Hsp70. Instead, these results suggest the importance of the bivalent binding of DjA1 dimer that limits unfavorable transitions of substrate conformations in protein folding.

Keywords: Chaperone Chaperonin, Heat Shock Protein, Kinetics, Protein Folding, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Bag1, DnaJ/Hsp40, Hsc70

Introduction

Molecular chaperones are a group of key molecules that act in numerous biological processes by assisting in conformational transitions of various proteins within the cell. The 70-kDa heat shock cognate protein (Hsc70, also known as Hsp73) in the cytosol engages in the folding of unfolded or newly translated proteins, prevention of misfolded proteins to form aggregates, assembly of protein complexes for signal transduction, translocation of proteins across organelle membranes, and degradation of proteins (reviewed in Refs. 1–3). Protein folding is the prominent function.

The Hsp70 protein usually functions as a chaperone system with various combinations of components including an Hsp70 protein, a DnaJ/Hsp40 protein, and a cochaperone(s). Several cytosolic DnaJ proteins have been investigated, and the biological significance of the canonical DnaJ proteins DjA1 (DnajA1: dj2/HSDJ/hdj2) and DjA2 (DnajA2: dj3/HIRIP4/hdj3) have been reported (4–6). The canonical DnaJ proteins are represented by Escherichia coli DnaJ and classified as type 1(7). The general features of the Hsp70 reaction cycle were mainly obtained from studies of the bacterial Hsp70 (DnaK) system (reviewed in Refs. 8 and 9). The chaperone activity of the Hsp70 is regulated by the nucleotide state. Hsp70-ATP induces an “open” state of the adjacent substrate-binding domain, and this state allows for the fast exchange of substrate polypeptides. Hsp70-ADP induces a “closed” state that tightly binds a substrate (slow exchange). These two states cycle with a rate determined primarily by the Hsp70 ATPase and nucleotide exchange. The cycle is further regulated by other components: a DnaJ/Hsp40 protein accelerates the ATPase of the Hsp70 (10), and the ADP/ATP exchange rate is enhanced by a group of cochaperones called nucleotide exchange factors (11). Many species of DnaJ/Hsp40 proteins and cochaperones are present in the cytosol. Some have a defined role in a specific biological process, whereas the others have redundant or alternative roles. How the individual components discriminate the chaperoning substrate proteins remains to be elucidated. The direct measurement of the initial binding processes of the components is obviously lacking.

The binding motifs for bacterial Hsp70 component (12, 13) and eukaryotic DnaJ proteins (14) have hydrophobic characteristics. These binding motifs are frequently present in protein sequences and are usually buried in the native structure (12). Exposure of these hydrophobic regions in an unfolded state frequently results in irreversible misfolding and aggregate formation. Most of the direct binding studies have investigated chaperone interactions with peptide substrates or aggregate-free proteins because of various technical difficulties in handling an unfolded protein.

Many studies have focused on the folding mechanism of the Hsp70 system (8, 9). The most comprehensive model shows that DnaJ binds a substrate polypeptide and then transfers the bound substrate to the substrate-binding cavity of Hsp70. This model couples the substrate transfer and ATP hydrolysis and provides an elegant explanation for the cooperative and sequential interactions among the substrate and the chaperones (15). The substrate transfer model for DnaJ is consistent with the published findings regarding several DnaJ proteins (16). However, a precise analysis is still needed to confirm the generality of the model by measuring the kinetics and stoichiometry of the chaperone binding to a whole molecule of substrate protein.

The current study was conducted to further elucidate the folding mechanism of the Hsc70 chaperone system. A folding-compatible concentration of individual components to refold an unfolded protein was examined. A surface plasmon resonance (SPR)2 method was developed to monitor the initial process of chaperone binding to the unfolded protein. A conformational change of the bound Hsc70 to the unfolded protein was suggested by tryptic digestion. The predominant presence of DjA1 dimer was detected by gel filtration and cross-linking experiments. The binding sites for the chaperones were investigated by screening 180 peptides derived from the substrate protein. All of the results clearly delineated the unexpected and essential features of the substrate recognition process by the Hsc70 and the DjA1 and argue against the generality of the hypothesis for the DnaJ proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Screening of Cellulose-bound Peptides

A peptide library covering the entire firefly luciferase was prepared by automated spot synthesis (PepSpot peptides; JPT Peptide Technologies GmbH). Approximately 5 nmol of peptides were synthesized in each grid with a spacing of 0.37 cm. The peptides were C-terminally attached to cellulose membrane via a (β-Ala)2 spacer. The screening followed previous procedures (12, 13) with some modifications. Rat Hsc70 (500 nm, purified as described in Ref. 4) was allowed to react with the PepSpot peptides as described for DnaK by Rüdiger et al. (12). Unbound Hsc70 was extensively washed out with Tris-buffered saline buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 137 mm NaCl) containing 0.05% Tween 20, and tightly bound Hsc70 on the PepSpot peptides was probed with Hsc70 antibody (B6; Stressgen). Human H6DjA1 (100 nm, purified as described in Ref. 4) was allowed to react with the PepSpot peptides as described for DnaJ (13). Unbound DjA1 was removed with Tris-buffered saline, and peptide-bound DjA1 was electrotransferred onto membranes. Transferred DjA1 was probed with a monoclonal antibody (MS225; NeoMarkers). The chaperone-antibody complexes on membranes were detected with appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence kits (GE Healthcare) using a chemiluminescence imaging system (LAS4000; Fujifilm Corp.).

Preparation of Liver Extract

Freshly dissected mouse liver was washed twice and homogenized with three strokes of Teflon pestle in 2 volumes of homogenization buffer (10 mm Hepes-NaOH, pH 7.2, 250 mm sorbitol, 50 mm KCl, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm NaF, 0.1 mm Na2VO4, and protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science)) at 4 °C. To obtain the cytosolic extract, the homogenate was sequentially centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min, 10,000 × g for 10 min, and 100,000 × g for 30 min. Typically, the protein concentration of the extracts ranged from 25 to 30 mg/ml. The extract was divided into aliquots and stored at −80 °C until use. The luciferase refolding assay was done as described (5).

SPR Analysis

The SPR measurement was conducted with a BIAcore 2000 system (GE Healthcare) at 25 °C in HKMB buffer (20 mm Hepes-KOH, pH 7.4, 120 mm potassium acetate, 1.6 mm magnesium acetate, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin) at a flow rate of 20 μl/min. The chaperone solutions were assembled on ice 3 min before the injection. Firefly luciferase (Sigma) was prepared at 2–10 μg/ml in 10 mm sodium acetate (pH 4.0) and coupled to the CM5 sensor chip via the standard amine coupling procedure. The coupled protein was completely denatured with multiple injections of 6 m guanidine HCl. To unfold the denatured protein in a chaperone-accessible conformation, 5 μl of 50 mm NaOH was passed through before sample injection. Similar binding was obtained with unfolding by guanidine HCl. After washing with HKMB buffer for 2 min, a chaperone protein was allowed to bind for 3 min. The sensor chip was regenerated with 15 μl of NaOH. The regeneration was conducted initially with Bag1 (5) and ATP when Hsc70 protein was injected and subsequently with NaOH. After 10 cycles of binding and regeneration, the decrease of response was <10% for the Hsc70 and <4.0% for the DjA1. The mass of the coupled protein was estimated from the resonance units according to the following equation: 1 resonance unit = 1 pg/mm2 (17).

Kinetic Analysis of Sensorgram Data

The kinetic constants were calculated from the sensorgrams using the BIAevaluation software (version 4.1) with predefined models. A molecular mass of 70.9 kDa was used for Hsc70 monomer and 91.7 kDa for DjA1 dimer to obtain the kinetic constants. The response was collected every 1 s, and all binding curves were subtracted by a mock reference flow cell. The data points corresponding to 20 s after the injection start and 20 s after the injection end were excluded from the fitting procedure as recommended in the BIAevaluation software handbook. The goodness of fit was assessed by inspecting the statistical value (x2 < 2) and the residuals.

Tryptic Digestion of Hsc70

The Hsc70 protein was 14C-labeled by reductive methylation using [14C]formaldehyde (PerkinElmer; 2.1 GBq/mmol) and NaBH4 (18). Luciferase was coupled to the CM-Sepharose beads as described to the sensor chip. The coupled luciferase (15 μl of a packed slurry of beads, 1.4 μg of luciferase/μl of beads) was successively unfolded with guanidine HCl and NaOH and rapidly exchanged to HKMB buffer using the Ultrafree-MC centrifugal filter device (Millipore; 0.1-μm pore). The unfolded luciferase was incubated with 20 μl of the HKM buffer containing 4 μg of the 14C-labeled Hsc70 (25 KBq) and 0.1 mm ATP. After 3 or 40 min of incubation, the solution was spun down, and the remaining protein in the filter cup was treated with 12 ng of trypsin in 20 μl of the buffer for 5 min. The treatment was halted by the addition of 3 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride, and the filtrate was recovered by centrifugation. The remaining proteins in the filter cup was further extracted with the sample buffer containing 4% SDS, and the filtrates were combined for analysis. The 14C-labeled Hsc70 (2 μg) in a nucleotide-bound state was also tested for the tryptic digestion. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by fluorography.

Detection of DjA1 Dimer

The DjA1 protein at 1 mg/ml was cross-linked with 4 mm of dimethyl suberimidate in 0.2 m triethanolamine HCl buffer (pH 8.5). The excess cross-linker was inactivated with 0.2 m ammonium acetate. The sample was analyzed by SDS-PAGE according to the procedure of Weber and Osborn (19). DjA1 protein (150 μg) was separated by a G3000SwXL gel filtration column (Tosoh Corp.) using a Hitachi 655 high pressure liquid chromatography system at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The running buffer was 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and 0.5 m NaCl, and absorbance at 280 nm was recorded. The protein did not elute with a lower salt buffer. The marker proteins were obtained from Sigma.

RESULTS

Nature of Luciferase Refolding

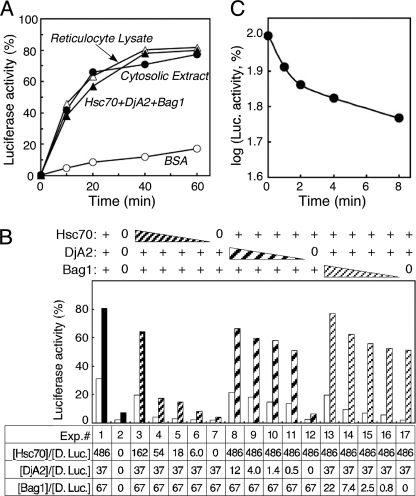

Both rabbit reticulocyte lysate and the reconstituted Hsc70 system have a potent chaperone activity in refolding denatured luciferase (4, 5). As shown in Fig. 1A, an extract from the mouse liver could efficiently refold denatured luciferase at 10 mg/ml. The concentrations of the purified Hsc70 and the DjA2 (as well as DjA1) used for the reconstitution were set to similar levels in comparison with those in the extract at 10 mg/ml (supplemental Fig. S1). There are three kinds of nucleotide exchange factors for the Hsc70 system (11), and Bag1 was selected for the experiments. A series of experiments with decreasing amounts of individual components showed that a substoichiometric amount of DjA2 but not Hsc70 could achieve significant refolding (Fig. 1B). DjA1 worked a similar manner as well (4). The absence of Bag1 resulted in slight reduction in total yield of refolding after 60 min, but the refolding proceeded almost linearly with a lag time at the initial 10 min as reported earlier (5). Next, the Hsc70 system was added with staggered timing to assess the folding competence of the unfolded protein (Fig. 1C). The unfolded luciferase lost its folding competence rapidly (t½ < 3.5 min) in the first few minutes. The loss of competence was slower in the subsequent period (t½ = 13 min). Approximately 60% of the competence was retained after 8 min of incubation without chaperones. These results prompted an investigation of the chaperone interaction with the unfolded protein using the SPR technique.

FIGURE 1.

Refolding activity of the Hsc70 system. A, refolding of chemically denatured firefly luciferase. The protein was refolded in the mixture without (open circle) or with 10 mg/ml of the cytosolic extract (filled circle). For comparison purposes, the luciferase was refolded in the reticulocyte lysate (40%, open triangle) or the combination of purified components (filled triangle, 200 μg/ml Hsc70, 20 μg/ml DjA2, and 20 μg/ml Bag1). Similar results were obtained with DjA1. B, refolding of denatured luciferase (5.7 nm) with variable amounts of chaperone components. The activity was monitored after 10 (open bars) and 60 min (solid or hatched bars). Hsc70 was added at 200 μg/ml (+), serial dilution by a factor of 3 (hatched box) and 0. DjA2 was added at 20 μg/ml (+), serial dilution by a factor of 3 (hatched box) and 0. Bag1 at 20 μg/ml (+), serial dilution by a factor of 3 (hatched box) and 0. The molar ratios of chaperone component and the luciferase are shown on the bottom of the graph. C, refolding of luciferase with delayed addition of the chaperone combination. The denatured luciferase was added into the refolding buffer without chaperones. The three chaperone components were added at the indicated times and allowed to refold for 60 min.

Several Hsc70 Proteins and Substoichiometric Numbers of DjA1 Bind to an Unfolded Luciferase

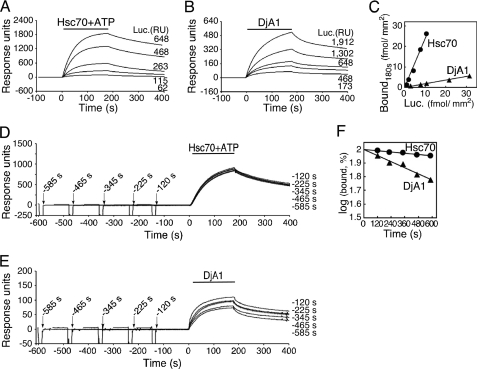

Various amounts of luciferase was coupled covalently to sensor chips and unfolded by a denaturant completely, and individual chaperone binding was investigated (Fig. 2, A and B). The amount of chaperone binding increased almost linearly with the amount of coupled protein (Fig. 2C). The binding of Hsc70 at the end of the association period well exceeded to the amount of coupled luciferase (the molar ratio was 2.4). Surprisingly, the amount of bound DjA1 was much lower than that of the coupled protein (the molar ratio was 0.18, DjA1 as a dimer). Although these molar ratios merely represented the amounts of chaperone binding during the course of substrate recognition, a single molecule of unfolded luciferase could bind several Hsc70 proteins and a substoichiometric amount of DjA1 dimer.

FIGURE 2.

Binding of chaperones to the coupled and unfolded luciferase. A and B, binding of Hsc70 (200 μg/ml or 2.8 μm) and DjA1 (20 μg/ml or 0.22 μm as a dimer) to various amounts of coupled luciferase. C, the molar ratios for binding of chaperones to the luciferase on sensor chips. The bound Hsc70 (A) and DjA1 (B) at the ends of association phases were plotted against amount of the luciferase. D and E, sensorgrams for delayed injections of Hsc70 (80 μg/ml) and DjA1 (20 μg/ml). The luciferase on the chip was unfolded prior to chaperone injection (arrow) and washed by the running buffer for the indicated times. F, decrease of chaperone binding capacity. The bound chaperones at the ends of association phases (D and E) were plotted versus the delayed injection times.

As expected, the binding of Hsc70 was ATP-dependent, whereas that of DjA1 was ATP-independent (supplemental Fig. S2). Neither Bag1 nor glutathione S-transferase (a control protein) bound to the coupled protein.

Unfolded Protein Dynamically Changes Its Conformation

The chaperone injection was started just after the unfolding of coupled protein at the indicated times (Fig. 2, D and E). The binding of the individual chaperone was apparently decreased in a first order reaction (Fig. 2F). The unfolded luciferase lost its binding capacity for DjA1 more rapidly (t½ = 13 min) than that for Hsc70 (t½ = 63 min). The binding capacities for Hsc70 and for DjA1 were estimated to be 95 and 80%, respectively, when unfolded protein was left for 2 min before chaperone injection. These results demonstrate that the unfolded and binding-competent protein on a chip gradually hides its binding sites for the chaperones by an intramolecular conformational change. However, the decrease of the binding capacity (Rmax) was relatively small within the time necessary for monitoring the association. We then attempted to evaluate the chaperone binding.

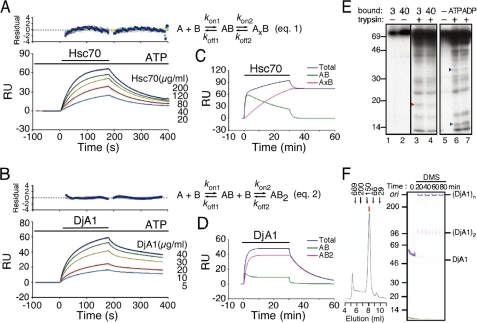

Hsc70 Binding Involves a Conformational Change, whereas DjA1 Binds at Two Sites

Sensorgrams were obtained with various concentrations of individual chaperones in the presence of ATP throughout (Fig. 3, A and B). The slopes of the secondary plots were not linear (supplemental Fig. S3), indicating that the binding process could not be described by a single reaction. Initial attempts to fit the experimental data globally to the various predefined models yielded unsatisfactory results (poor x2 values; data not shown). This may be due to the metastable nature of unfolded proteins (Fig. 2, D–F). The binding competence for the chaperones was decreased in a time-dependent manner (and chaperone concentration-dependent), and this severely affected the association rate constants and the maximum binding. However, the decrease in the binding capacity may have little influence during the dissociation phase. In fact, the secondary plots for the dissociation phase had very similar curves (supplemental Fig. S3). Consequently, only the dissociation rate constants (koff values) were globally fitted. This approach gave satisfactory fitting results. Hsc70 showed a curve consistent with a two-state reaction model and the DjA1 with a bivalent analyte model, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Binding of Hsc70 and DjA1 to coupled luciferase. A and B, sensorgrams (colored curves) for various amounts of the respective chaperones. The running buffer was supplemented with 1 mm ATP. The model equations used to fit the model are shown. The residual plots (top panels) were also provided to give a graphical indication of experimental data deviation from the fitted curves (black). C and D, simulation of the sensorgrams with longer time periods (30 min of association and 30 min of dissociation). The curves were obtained from the kinetics parameters in Table 1 using the BIAsimulation software program. The bulk refractive index was subtracted from the total data. E, tryptic digestion of Hsc70. The 14C-methylated Hsc70 was allowed to bind to the unfolded luciferase beads (lanes 1–4). After the incubation for 3 or 40 min, the bound Hsc70 was separated and treated with trypsin for 5 min (lanes 3 and 4). The [14C]Hsc70 with a nucleotide was also treated (lanes 6 and 7). The blue triangles represent bands found only in [14C]Hsc70 samples without unfolded substrate. The red triangle represents the band with the bound [14C]Hsc70 samples (lanes 3 and 4). The amount of samples: 5% (lanes 1 and 2); 50% (lanes 3, 4, 6, and 7); 0.2 μg of [14C]Hsc70 (lane 5). F, detection of DjA1 dimer. The DjA1 protein was eluted mainly at a position corresponding to 100,000 by a gel filtration experiment (red arrow, left panel). The DjA1 protein was cross-linked with dimethyl suberimidate, separated by SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (right panel).

The kinetic constants were summarized in representative conditions (Table 1). Most of the bound Hsc70 reached a tightly bound state (AxB, t½ = 17 min) when sensorgrams were simulated for longer association periods (Fig. 3, C and D). In contrast, the bound DjA1 rapidly reached an equilibrium state with a bivalent form (AB2, t½ = 3 min). The bivalent form of DjA1 on the unfolded protein dissociates much faster than the tight form of Hsc70.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic constants for the interaction of chaperones with unfolded luciferase

The rate constants were calculated from the responses in Fig. 3. RU, resonance units.

| Chaperones | kon1 | koff1 | KD1a | kon2 | koff2 | KD2a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m−1s−1 | s−1 | μm | s−1 | |||

| Hsc70b | 4.9 × 103 | 1.0 × 10−2 | 2.1 | 1.0 × 10−3s−1 | 5.8 × 10−7 | 5.6 × 10−4 |

| DjA1c | 4.0 × 104 | 3.7 × 10−2 | 0.91 | 2.5 × 10−4RU−1s−1 | 1.9 × 10−3 | 7.7 RU |

a The KD values were calculated from the kon and koff values.

b The responses with 200 μg/ml of Hsc70 were analyzed by the two-state model. The multiplicity of the binding sites was not considered.

c The responses with 20 μg/ml of DjA1 were analyzed by the bivalent analyte model.

A two-state (conformational change) reaction was widely expected for the binding process of Hsp70 proteins. The time required for the formation of the tightly bound state was approximately the same as the turnover of ATPase activity (t½ = 20 min) (5). Therefore, the conformational change may implicate a change in the binding status of Hsc70 after the ATP hydrolysis (a switch from the open to the closed state of the substrate-binding domain). Consistent with this notion, the 14C-labeled Hsc70, which bound to the unfolded protein, was found to have become more resistant to tryptic digestion (Fig. 3E). The SPR analysis also demonstrated that a bivalent binding model is suitable for DjA1. The predominant presence of DjA1 dimer was detected by gel filtration and cross-linking experiments (Fig. 3F). The bivalent analyte model also demonstrated a better fit for the other DnaJ proteins (supplemental Fig. S4), but none of the DnaJ proteins fully saturated the binding sites at 20 μg/ml (∼0.2 μm).

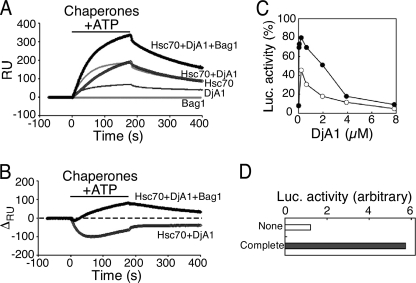

DjA1 Decreases Hsc70 Binding in the Absence of Bag1

The individual addition of Hsc70 and DjA1 at folding-compatible concentrations revealed that the amount of Hsc70 binding always exceeded that of DjA1 (Fig. 4A). The response was lower than the sum of responses from the individual chaperones during the association period when the Hsc70 and the DjA1 were added to the unfolded protein simultaneously (Fig. 4, A and B). The slope of dissociation showed a similar curve to that for the single addition of Hsc70, thus indicating that the contribution of the bound DjA1 was slight. The slow binding kinetics with the two components was consistent with the initial lag times observed for the refolding reaction (4). The DjA1 accelerates the intrinsic ATPase activity of Hsc70 (5), and a DnaJ protein binds to an Hsp70-ATP in solution with a dissociation constant of 0.5–0.6 μm (20, 21), thus leading to the rapid formation of Hsp70-ADP. Therefore, the simultaneous addition of Hsc70 and DnaJ protein lowers the concentrations of both Hsc70-ATP and free DnaJ protein in solution and causes detrimental effects on the chaperone binding to the unfolded protein. This is further supported by the observations that a higher amount of DjA1 impaired rather than facilitated the refolding yield (Fig. 4C) and that the addition of a component with staggered timing showed little difference between the order of addition (supplemental Fig. S5).

FIGURE 4.

Simultaneous addition of chaperone components. A, sensorgrams of the interaction between chaperone combinations and the luciferase (thick curves). ATP, together with the chaperone components, was only added during the association phase. B, differences between the combinational and individual chaperon binding. C, refolding of luciferase with a higher amount of DjA1. The refolding mixtures contained Hsc70 (2.8 μm) and variable amount of DjA1 (0–7.9 μm) with (closed circles) or without (open circles) Bag1 (0.77 μm). The activity was monitored after 60 min. D, refolding of the denatured luciferase on the sensor chip. The coupled luciferase on the sensor chip was manually processed for the unfolding procedure. The chip was immersed in the HKMB-ATP solution with or without the chaperone combination for 30 min and soaked into the luciferase assay buffer to check the activity.

The poor binding of the two components was improved by further addition of Bag1. The response from the simultaneous addition of the three components was similar to the sum of the responses from the individual addition in the initial 20 s of association period (Fig. 4B). Thereafter, the response exceeded the sum of the responses. The precise kinetics of the individual binding components (directly or indirectly) is yet to be determined; however, there was no synergistic effect during the initial association period. These results indicate that ATP-bound Hsc70 and free DjA1 initially bind to the unfolded protein independently, and a proper folding reaction can be started only after a sufficient number of Hsc70 molecules and a DjA1 dimer bind to an unfolded protein.

The ability of unfolded luciferase on a chip to be folded by the bound chaperones was investigated. As illustrated in Fig. 4D, the luciferase on a chip could be refolded in an Hsc70 system-dependent manner. This simple SPR method yielded new insights into the binding mechanism of chaperone components to a metastable unfolded protein.

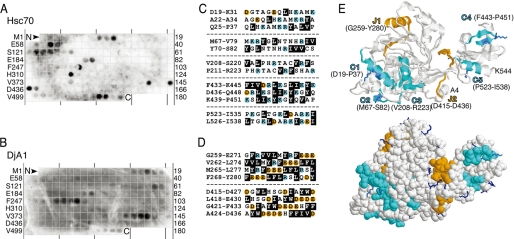

Screening of Binding Peptides for Hsc70 and DjA1

Cellulose-bound PepSpot peptides were screened to determine the binding site(s) within luciferase sequence recognized by Hsc70 and DjA1. The PepSpot peptides were composed of 13-mers that overlap with adjacent peptides by 10 residues and presented all the potential binding sites to the chaperones. Rüdiger et al. (12, 13) successfully determined binding motifs for the bacterial Hsp70 system with similar peptide arrays. The PepSpot membranes were individually incubated with Hsc70 and DjA1, respectively, to equilibrium. The PepSpot membrane was washed stringently and immunodetected directly because the Hsc70 binding was very tight at equilibrium (Fig. 4). Five clusters of consecutive spots as well as some isolated spots gave positive signals (Fig. 5A). The clusters were fewer and shorter than those reported for the bacterial DnaK (12), and most of the clusters overlapped with those for DnaK. The similarity in the binding specificity for DnaK and Hsc70 has also been previously reported (22). The screening for the DjA1 binding sites was performed according to the published protocol for DnaJ (13). The DjA1 binding gave two clusters of consecutive spots with strong signals (Fig. 5B). These clusters overlapped with those for the bacterial DnaJ (13). The overlap was only four residues (Phe433–Asp436) among the clusters for Hsc70 and DjA1 (Fig. 5, C and D). The identified clusters were scattered along the sequence and denoted in the native structure of luciferase (Fig. 5E).

FIGURE 5.

Chaperone binding to cellulose-bound peptide scan. A and B, a peptide scan derived from sequences of luciferase was screened for Hsc70 (A) and DjA1 (B) binding. The last spots of rows (right) and the N-terminal residues of peptides of the first spots of rows (left) are indicated. C and D, differential binding of Hsc70 and DjA1 to peptides. Peptides that bind to Hsc70 contain several large hydrophobic and aromatic residues (Leu, Ile, Phe, Val, Trp, and Tyr; black boxes) with basic residues (Arg and Lys; blue circles). Peptides that bind to DjA1 contain large hydrophobic and aromatic residues with multiple acidic residues (Glu and Asp; yellow circles). E, ribbon and space filling representations of the structure of native luciferase from the x-ray structure (Protein Data Bank entry 1LCI) (43) using the RasMol 2.7 software program. The cyan and yellow regions indicate the binding sites for Hsc70 (C) and DjA1 (D), respectively. Lysine residues in the Hsc70 binding sites are indicated by sticks. The other lysine residues (31 of 40 residues) are blue sticks (bottom).

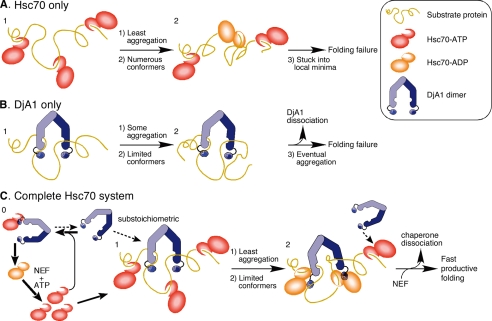

DISCUSSION

The current study revealed three key findings regarding the initial binding process of the Hsc70 components, thus indicating a dynamic mechanism of folding reaction. First, the amount of DjA2 as well as DjA1 could be strikingly decreased to a substoichiometric level with that of the unfolded protein for significant folding (Fig. 1). Intermolecular interactions are disfavored in a diluted condition, and the folding competence of unfolded luciferase was relatively maintained in a second phase (Fig. 1C). This observation prompted an investigation of the chaperone binding to the unfolded protein on a sensor chip by SPR measurement, and the results provided the second key finding. The Hsc70 binding was consistent with a two-state model that allows a step for ATP hydrolysis, whereas the DjA1 binding to a bivalent model indicated a dimer function (Fig. 3). Multiple Hsc70 proteins and a substoichiometric amount of DjA1 dimer independently bound to a substrate protein (Fig. 2). The third key finding was revealed by the screening of the PepSpot peptides (Fig. 5). There were discrete binding sites for the Hsc70 and the DjA1. There was no overlap between the sites for Hsc70 and for DjA1 binding. All of these findings argue against the possible idea that a bound DnaJ protein on a substrate protein recruits and targets the Hsp70 protein. This was further supported by the observation that the initial association rate of Hsc70 was faster than that of DjA1 at folding-compatible concentrations (Fig. 4).

Hsc70 Binding to the Unfolded Protein

It was surprising to find a large amount of Hsc70 bound to the unfolded protein. The SPR analysis suggested that Hsc70 bound a maximum of three or four sites (Figs. 2 and 3). This estimation is consistent with the number of clusters that were identified in the peptide screening (Fig. 5). The luciferase polypeptide contains 40 lysine residues, among which nine residues are present in the identified clusters. The amine coupling procedure utilizes a small number of lysine residues within the polypeptide, and this was likely to have detrimental effects on Hsc70 binding and subsequent folding reaction. In any case, several Hsc70 molecules bind to a luciferase molecule in an unfolded state.

The unfolded luciferase gradually lost its binding competence (Fig. 2). The appropriate number of Hsc70 molecules cannot saturate the multiple binding sites at a lower Hsc70 concentration (Fig. 3A), and this results in poor refolding (Fig. 1B). The primary function of Hsc70 appears to be the prevention of inappropriate hydrophobic interactions, and the saturation of the multiple binding sites is necessary for the unfolded protein to reduce the chance of a misfolded conformation (Fig. 6). Therefore, the Hsc70 binding at multiple sites on the unfolded protein is a prerequisite for the refolding reaction. It is generally postulated that multiple Hsp70 molecules bind to a protein and support unidirectional translocation across organelle membranes (23, 24).

FIGURE 6.

Model for refolding of luciferase by the Hsc70 system. Step 1, multiple Hsc70 proteins and a dimer of DjA1 independently bind to the proper binding sites on an unfolded substrate protein. A, Hsc70 only. Step 2, the bound Hsc70-ATP molecules suppress hydrophobic interactions among the binding sites. Conversion to the ADP form is slow. The complex undergoes multiple transitions in an energy landscape. The complex constraints on the transitions or gets stuck into the local minima of the landscape. B, DjA1 only. Step 2, a U-shaped dimer of DjA1 binds to two distant sites on a substrate and reduces a considerable range of the conformational transitions. The DjA1 binding prevents some hydrophobic interactions, but DjA1 dissociation results in eventual aggregation. C, the complete Hsc70 system. Step 0, the Hsc70-ATP and free DjA1 are in equilibrium in the solution. Step 2. The bound Hsc70-ATP suppresses the unfavorable interactions, whereas the bound DjA1 reduces the range of transitions. Some of the bound DjA1 accelerates ATP hydrolysis of the bound Hsc70. A free DnaJ protein in solution may act on the other bound Hsc70-ATP. A nucleotide exchange factor facilitates dissociation of the bound Hsc70-ADP.

The finding that the unfolded protein has multiple sites for Hsc70 binding suggests that a model that takes into consideration the multiple parallel binding reactions with two-state conformational changes on individual binding sites is a more plausible model. However, this model is too complicated to solve based on the current fitting algorithms. Therefore, a practical approach was used to fit the experiment data with a simple “two-state reaction” model. Although this approximation assumes few differences among the affinities of the individual binding sites, the model gave satisfactory results with the statistical values (x2 < 2) and includes the basic features of Hsc70 binding at the initial step. The apparent first dissociation constant of the Hsc70-ATP (KD1) was at the micromolar level (Table 1). The KD1 value is comparable with the dissociation constants for other Hsp70s and peptide substrates (25, 26) or native σ32 (27). The association rate constant (kon1) is a little lower than the kon value reported for DnaK-σ32 (27).

The association rate of the second step is much slower than that of the first step (Fig. 3 and Table 1). The time required for the half-maximum binding of the second step (Fig. 3C, t½ = ∼17 min) is very close to the turnover of the ATPase (t½ = ∼20 min) (5). A slight increase in the binding to the unfolded protein was also observed for the labeled Hsc70 (Fig. 3E, lanes 1 and 2), and it appeared to be more resistant to tryptic digestion (Fig. 3E, lanes 3 and 4). In the absence of the unfolded protein, some tryptic fragments of the Hsc70 in an ADP state were slightly weaker that those in an ATP state (Fig. 3E, lanes 6 and 7). Unfolded proteins accelerate the ATPase activity of Hsp70 in combination with the other components (15). However, the presence of unfolded luciferase had little effect on the ATPase of DnaK without other components (15). The tight binding of Hsc70 in the second step is corroborated by many examples of stable complexes found in Hsc70 and various proteins within the cells (for example, please see Ref. 28).

Binding of DnaJ Proteins to the Unfolded Protein

Either of the two type 1 DnaJ proteins, DjA1 and DjA2, was an essential component of the Hsc70 system for the refolding reaction (5). The DjA1 was predominantly dimer, and the monomeric species of DjA1 was hardly detected (Fig. 3F). The structural studies revealed that the type 1 DnaJ proteins exist as “U-shaped” dimers (29, 30). The dimeric binding to a substrate protein was suggested for the bacterial DnaJ (31); however, no kinetic evidence of bivalency has been reported for DnaJ protein binding to an unfolded protein. The present study indicated that DjA1 reasonably bound to an unfolded protein bivalently (Fig. 3), and there were two clusters of strong binding sites (Fig. 5). Apart from the issue of the amount of binding, the bivalent model nicely describes the dimeric DjA1 binding. We also found minor species of DjA1 with a high molecular weight (Fig. 3F). The DjA1 protein tends to form aggregates, and it is adsorbed on the tube wall or the column under a low salt buffer.3 These problems were relieved by the addition of either protein (such as albumin) or a high amount of salt (for instance, 0.5 m NaCl). It is therefore unlikely that these minor species of DjA1 participate in the refolding reaction.

The two binding sites for DjA1 are separated by ∼150 residues and were located in two distinct domains (Fig. 5E). Obviously, the bivalent binding considerably restricts the range of conformational transitions for the unfolded protein (Fig. 6), and this would be an important and necessary function for a type 1 DnaJ protein in the refolding reaction.

The DjA1 as well as DjA2 bound to the unfolded luciferase in a substoichiometric manner (Figs. 2 and 3 and supplemental Fig. S4). This contrasts with the finding that the Hsc70 binding showed a higher stoichiometry. This was rather surprising; however, a substoichiometric amount of DjA1 to the unfolded luciferase could permit significant refolding (Fig. 1B). Hence, the serial DjA1 binding to the multiple Hsc70-bound substrate promotes the folding reaction.

The apparent first dissociation constant of the DjA1 (KD1) was found to be 0.9 μm (Table 1) and was comparable with the dissociation constant reported for DnaJ-σ32 (27). The initial association rate of the Hsc70 to the unfolded protein was faster than that of the DjA1 in folding-compatible conditions (Fig. 4). Therefore, these results not only demonstrate the independent processes of Hsc70 and DjA1 binding but also suggest that the slow saturation of the binding sites for DjA1 determines the rate of the folding reaction.

The simultaneous addition of DjA1 and DjA2 to the Hsc70 system has little effect on the refolding reaction (4, 5). The DjA2 binding to the unfolded protein was comparable with the DjA1 binding (supplemental Fig. S4). It is likely that DjA1 and DjA2 compete for the same binding sites, and a bound DnaJ protein functions similarly for the refolding reaction. The DjB1, in contrast, was dispensable for the refolding reaction (5), and the SPR measurement showed a small amount of bivalent binding with a high bulk refractive index (supplemental Fig. S4). The high refractive index indicates that this type 2 DnaJ protein associates to the unfolded protein in a rapid and loose manner. This feature may promote recruitment of Hsc70 to newly synthesized proteins for the de novo folding (2) and accelerate the conversion of the bound Hsc70-ATP into the Hsc70-ADP. Accordingly, the direct binding of the DnaJ proteins was not observed for the nascent polypeptides (32). The physiological amount of DjB1 showed little bivalent binding (supplemental Fig. S4). This may be why a larger amount of DjB1 and an extra addition of the reticulocyte lysate was necessary for efficient refolding (33). The DjB1 is not the prime DnaJ protein for the refolding of the unfolded protein (4, 5), and the DjB1 knock-out animal showed no obvious abnormal phenotype under normal conditions (34).

Initial Recognition of Substrate Proteins by Hsc70 Components

The SPR measurements of individual chaperone binding in folding-compatible concentrations demonstrated that the initial association rate of DjA1 was slower than that of the Hsc70. Attenuated binding was observed with the simultaneous addition of Hsc70 and DjA1, but it was apparently improved by further addition of Bag1 (Fig. 4). A DnaJ protein promotes hydrolysis of the ATP bound to the Hsc70 and generates ADP-bound Hsc70, whereas Bag1 exchanges bound ADP to ATP and restored the population of ATP-bound Hsc70 (35). Furthermore, a DnaJ protein complexes with Hsp70-ATP in solution with dissociation constants at the submicromolar level (21, 36), whereas the Bag1 complexes with Hsc70 at a dissociation constant of 1–3 μm (37). Therefore, the effective concentrations of the Hsc70-ATP and DnaJ protein that can bind to the unfolded protein differ significantly from the original concentrations of the components. They are dependent on the kinds, ratio, and concentrations of the constituted components.

The postulated roles for DnaJ protein in targeting of Hsp70 and transferring of substrate to the Hsp70 are not always operative in the refolding of luciferase. The conformational changes in the inactivation process of σ32 led to a similar conclusion by the bacterial DnaK-DnaJ system (38). Native σ32 appears to have two distinct binding sites for DnaK and DnaJ. Therefore, the canonical type 1 DnaJ proteins bind to distinct sites on the substrates without subsequent transferring of the bound substrate to Hsp70 proteins (38). Some noncanonical DnaJ proteins (types 2 and 3) are membrane-anchored and engage in protein translocation across organelle membranes (16). Although the proximal effect of a DnaJ protein for recruiting an Hsp70 was reported previously (39), the transferring of the DnaJ-bound site to Hsp70 is remained to be determined. In any case, distinct binding mechanisms may exist among the Hsp70 systems dependent upon the type of accompanying DnaJ protein.

The current findings emphasize the importance of interactions between an unfolded protein and chaperones. Although the refolding on a sensor chip seems not to be perfect, the SPR analysis demonstrated important features of the unfolded protein recognition by the Hsc70 system at the initial step. Furthermore, they provide insights into the mechanistic action of the DnaJ protein among various cochaperone-mediated biological processes of the other Hsp70 systems. The substrate polypeptides have diverse fates on the biological processes. Some have an appropriate binding site(s) to be mediated by the canonical DnaJ protein as an Hsc70 system. However, the slow and substoichiometric binding of DjA1 to the unfolded protein suggests that the remaining Hsc70-bound but DjA1-unbound substrates have a good chance to be recognized by either other DnaJ proteins or other cochaperones that have tetratricopeptide repeat domains. The tetratricopeptide repeat-containing cochaperones bind to the EEVD-terminal sequence of Hsc70 and modulate the Hsc70 system to engage in other biological processes besides folding (40–42).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We give our thanks to Rieko Shindo and Yasuko Indo for valuable technical assistance.

This work was supported by Grants 19058010 and 20590287 from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (to K. T.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

K. Terada, unpublished observation.

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bukau B., Horwich A. L. (1998) Cell 92, 351–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartl F. U., Hayer-Hartl M. (2002) Science 295, 1852–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsell D. A., Lindquist S. (1993) Annu. Rev. Genet. 27, 437–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terada K., Kanazawa M., Bukau B., Mori M. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 139, 1089–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terada K., Mori M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 24728–24734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terada K., Yomogida K., Imai T., Kiyonari H., Takeda N., Kadomatsu T., Yano M., Aizawa S., Mori M. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 611–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohtsuka K., Hata M. (2000) Cell Stress Chaperones 5, 98–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fink A. L. (1999) Physiol. Rev. 79, 425–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayer M. P., Bukau B. (2005) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 62, 670–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley W. L. (1998) Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 222–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendrickson W. A., Liu Q. (2008) Structure 16, 1153–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rüdiger S., Germeroth L., Schneider-Mergener J., Bukau B. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 1501–1507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rüdiger S., Schneider-Mergener J., Bukau B. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 1042–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J., Qian X., Sha B. (2003) Structure 11, 1475–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laufen T., Mayer M. P., Beisel C., Klostermeier D., Mogk A., Reinstein J., Bukau B. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 5452–5457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Summers D. W., Douglas P. M., Ramos C. H., Cyr D. M. (2009) Trends Biochem. Sci. 34, 230–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stenberg E., Persson B., Roos H., Urbaniczky C. (1991) J. Colloid Interface Sci. 143, 513–526 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chappell T. G., Konforti B. B., Schmid S. L., Rothman J. E. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 746–751 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber K., Osborn M. (1969) J. Biol. Chem. 244, 4406–4412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang R. F., Greener T., Barouch W., Greene L., Eisenberg E. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 6141–6145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suh W. C., Lu C. Z., Gross C. A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30534–30539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gragerov A., Gottesman M. E. (1994) J. Mol. Biol. 241, 133–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neupert W., Herrmann J. M. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 723–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rapoport T. A. (2007) Nature 450, 663–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flynn G. C., Chappell T. G., Rothman J. E. (1989) Science 245, 385–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pierpaoli E. V., Sandmeier E., Baici A., Schönfeld H. J., Gisler S., Christen P. (1997) J. Mol. Biol. 269, 757–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamer J., Multhaup G., Tomoyasu T., McCarty J. S., Rüdiger S., Schönfeld H. J., Schirra C., Bujard H., Bukau B. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 607–617 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beckmann R. P., Mizzen L. E., Welch W. J. (1990) Science 248, 850–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borges J. C., Fischer H., Craievich A. F., Ramos C. H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 13671–13681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sha B., Lee S., Cyr D. M. (2000) Structure 8, 799–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wickner S. H. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 2690–2694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagata H., Hansen W. J., Freeman B., Welch W. J. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 6924–6938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minami Y., Höhfeld J., Ohtsuka K., Hartl F. U. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19617–19624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uchiyama Y., Takeda N., Mori M., Terada K. (2006) J. Biochem. 140, 805–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Höhfeld J., Jentsch S. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 6209–6216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barouch W., Prasad K., Greene L., Eisenberg E. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 4303–4308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sondermann H., Scheufler C., Schneider C., Hohfeld J., Hartl F. U., Moarefi I. (2001) Science 291, 1553–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez F., Arsène-Ploetze F., Rist W., Rüdiger S., Schneider-Mergener J., Mayer M. P., Bukau B. (2008) Mol. Cell 32, 347–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Misselwitz B., Staeck O., Rapoport T. A. (1998) Mol. Cell 2, 593–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cyr D. M., Höhfeld J., Patterson C. (2002) Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 368–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith D. F. (2004) Cell Stress Chaperones 9, 109–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young J. C., Barral J. M., Ulrich Hartl F. (2003) Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 541–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conti E., Franks N. P., Brick P. (1996) Structure 4, 287–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.