Abstract

Background and purpose:

To determine whether KMUP-1, a novel xanthine-based derivative, attenuates isoprenaline (ISO)-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rats, and if so, whether the anti-hypertrophic effect is mediated by the nitric oxide (NO) pathway.

Experimental approach:

In vivo, cardiac hypertrophy was induced by injection of ISO (5 mg·kg−1·day−1, s.c.) for 10 days in Wistar rats. In the treatment group, KMUP-1 was administered 1 h before ISO. After 10 days, effects of KMUP-1 on survival, cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, the NO/guanosine 3′5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP)/protein kinase G (PKG) and hypertrophy signalling pathways [calcineurin A and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2] were examined. To investigate the role of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) in the effects of KMUP-1, a NOS inhibitor, Nω-nitro-L-arginine (L-NNA) was co-administered with KMUP-1. In vitro, anti-hypertrophic effects of KMUP-1 were studied in ISO-induced hypertrophic neonatal rat cardiomyocytes.

Key results:

In vivo, KMUP-1 pretreatment attenuated the cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and improved the survival of ISO-treated rats. Plasma NOx (nitrite and nitrate) and cardiac endothelial NOS, cGMP and PKG were all increased by KMUP-1. The activation of hypertrophic signalling by calcineurin A and ERK1/2 in ISO-treated rats was also attenuated by KMUP-1. All these effects of KMUP-1 were inhibited by simultaneous administration of L-NNA. Similarly, in vitro, KMUP-1 attenuated hypertrophic responses and signalling induced by ISO in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes.

Conclusions and implications:

KMUP-1 attenuates the cardiac hypertrophy in rats induced by administration of ISO. These effects are mediated, at least in part, by NOS activation. This novel agent, which targets the NO/cGMP pathway, has a potential role in the prevention of cardiac hypertrophy.

Keywords: KMUP-1, cardiac hypertrophy, isoprenaline, nitric oxide, calcineurin A

Introduction

Cardiac hypertrophy is often induced in pathological conditions such as pressure or volume overload and has been regarded as an adaptive response of cardiac muscle (Sadoshima and Izumo, 1997). However, prolonged cardiac hypertrophy is associated with a significant increase in the risk of heart failure, leading to increased cardiovascular mortality (Levy et al., 1990).

There are multiple signalling and transcription pathways that contribute to hypertrophic remodelling (Frey et al., 2004). In addition, emerging evidence suggests that the nitric oxide (NO)/guanosine 3′5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) pathway plays an important role in the modulation of cardiac hypertrophy. For example, overexpression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS) in mice has been shown to attenuate cardiac hypertrophy (Ozaki et al., 2002). Increasing myocardial cGMP by the phosphodiesterase inhibitor sildenafil has been found to exert cardioprotection with decreasing hypertrophic responses (Hassan and Ketat, 2005;Takimoto et al., 2005). Therefore, activation of NO/cGMP pathway may be a potential therapeutic strategy in the prevention or treatment of cardiac hypertrophy.

It has been demonstrated that extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK)1/2 are essential players in many cellular and physiological signalling responses. β-Adrenoceptor-mediated stimulation of ERK1/2 may play a role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Aberrant ERK1/2 signalling is in part responsible for significant pathologies such as hypertrophy, proliferation and oncogenesis (Ramos, 2008). Much investigation has focused on the signalling pathways controlling cardiac hypertrophy, including Ca2+/calmodulin-activated phosphatase calcineurin A (Fiedler and Wollert, 2004). It has been reported that activation of Ca2+ induces the phosphorylation of calcineurin A, which then translocates calcineurin-nuclear factor activation transcription into the nucleus for gene expression, and in turn enhances hypertrophy or apoptosis of cardiomyocytes (Molkentin, 2004).

KMUP-1 is a unique xanthine and piperazine derivative developed by our group. Our recent studies indicate that KMUP-1 can activate soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), increase cGMP and inhibit phosphodiesterases, resulting in relaxations of smooth muscles in aorta (Wu et al., 2001), corporeal carvenosa (Lin et al., 2002) and trachea (Wu et al., 2004). KMUP-1 has been shown to suppress tumour necrosis factor-α-induced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in tracheal smooth muscle cells and the sGC/cGMP/protein kinase G (PKG) expression pathway is involved in this effect (Wu et al., 2006). Moreover, KMUP-1 has been found to have anti-proliferation activity in the prostate epithelial cell and inhibit tumour formation in prostate cancer (Liu et al., 2007; 2009;). However, it is not known whether it can also activate the NO/cGMP pathway in the heart with resultant cardioprotective effects. Thus, the aims of this study were to investigate in vivo and in vitro whether KMUP-1 has an anti-hypertrophic effect in cardiac hypertrophy, and if so, whether the anti-hypertrophic effect is mediated by the NO pathway.

Methods

Experimental animals

Male Wistar rats weighing 250 to 300 g were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Breeding and Research Centre (Taipei, Taiwan). They were housed under conditions of constant temperature and controlled illumination (light on between 7 h 30 min and 19 h 30 min). Food and water were available ad libitum. All protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Kaohsiung Medical University.

Experimental groups and treatment

Rats were randomly divided into five groups. (i) Control group (n = 10): normal saline was given s.c. for 10 days; (ii) isoprenaline (ISO) group (n = 20): to induce cardiac hypertrophy, ISO 5 mg·kg−1·day−1 s.c. was administered for 10 days; (iii) ISO/KMUP-1 group (n = 10): KMUP-1 was injected i.p. for 10 days at a dose of 0.5 mg·kg−1·day−1, prior to ISO 5 mg·kg−1·day−1; (iv) ISO/L-NNA (Nω-nitro-L-arginine) 10/KMUP-1 group (n = 10): drugs given to this group were the same as the ISO/KMUP-1 group, except that the NOS inhibitor, L-NNA at a dose of 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 was added to the drinking water of this group; and (v) ISO/L-NNA 20/KMUP-1 group (n = 10): drugs given to this group were the same as the ISO/L-NNA 10/KMUP-1 group, except that a higher dose of L-NNA (20 mg·kg−1·day−1) was administered. After 10 days of treatment, under pentobarbitone anaesthesia, the hearts were removed for assessment. Myocardial interstitial fibrosis was stained by Masson's trichrome. All hearts were sectioned across the ventricles for histological analyses. The extent of fibrosis in both the viable and infarcted region of the left ventricle was quantified using Masson's trichrome stained heart sections.

Determination of survival and heart weight indices

The number of survivors in each group was recorded daily until the end of study. After the defined treatment period, the rats were killed by an i.p. injection of 40 mg·kg−1 pentobarbitone sodium. The heart weight and body weight were both recorded. The heart weight index was calculated by dividing the heart weight by the body weight.

Measurement of plasma nitrite and nitrate (NOx)

Plasma NOx was measured by Griess reaction. In brief, blood was sampled from the aorta and was centrifuged at 370× g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatants were extracted three times. A total of 150 µL of the samples were incubated with 150 µL of the Griess reagent (part I: 1% sulphanilamide; part II: 0.1% naphthylethylene diamide dihydrochloride and 2% phosphoric acid) at room temperature. Ten minutes later, the absorbance was measured at 540 nm using an automatic plate reader, and the NOx concentrations were expressed as µmol·L−1 and calculated using a standard curve of NOx.

cGMP determination

Intracellular cGMP concentrations were assayed as previously described (Wu et al., 2001). In brief, the left ventricle was sonicated in ice-cold 5–10% trichloroacetic acid and then centrifuged at 13 000× g for 60 min at 4°C. Then the protein content was determined using Bio-Rad protein assay. The cGMP level was determined by a commercially available radioimmunoassay kit subsequently (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Culture of neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes

Cardiomyocytes were obtained from 1–3-day-old neonatal Wistar rat ventricles as previously described (Morisco et al., 2001). Briefly, the ventricular cells were dispersed by digestion with trypsin and collagenase II. The cell supernatant was collected by centrifugation, and the pellet was resuspended in fetal bovine serum. The above steps were repeated 7–10 times until the ventricle was completely digested. Cells were plated onto collagen-coated culture dishes or cover slips and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mmol·L−1 L-glutamate and 100 µmol·L−1 5-bromodeoxyuridine. To induce hypertrophy, cardiomyocytes were cultured in serum-free medium for at least 24 h and then treated with 1 µmol·L−1 ISO for 48 h.

Preparation of cytosolic and nuclear protein extracts

Separation and preparation of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were performed using NE-CER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). In brief, cardiomyocytes were harvested and resuspended in 100 µL of ice-cold cytoplasmic extraction reagent (CER) I containing protease inhibitor, and incubated on ice for 10 min. Then 5.5 µL of ice-cold CER II was added to the cell suspension. After being vortexed for another 5 s, the cell extract was centrifuged at 4°C for 5 min at maximum speed, and the supernatant, which embraces the cytoplasmic fraction, was transferred to a fresh, prechilled tube and stored at −80°C. The pellet was resuspended in 50 µL of ice-cold nuclear extraction reagent for a total of 40 min. The insoluble fraction was precipitated by centrifugation at 4°C for 10 min at maximum speed, and the supernatant was used for nuclear fraction. The protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay. For subcellular location determination, the protein extracts were reacted with antibodies against lamin B (ProteinTech Group, Chicago, IL, USA), the nuclear marker, and β-actin, the cytoplasmic marker respectively.

Western blot analysis

Lysates of cardiomyocytes and cardiac tissue were prepared as described previously (Wu et al., 2009). In brief, cardiomyocytes were made quiescent for 24 h, followed by incubation in the absence or presence of KMUP-1 for 1 h and then stimulated with ISO (1 µmol·L−1). Reactions were terminated by washing twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline, and the cells were then harvested. Left ventricle was homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer and protease inhibitor (Sigma). The homogenate was centrifuged at 830× g for 60 min at 4°C, and supernatant was recovered as the total cellular protein. Total protein from each sample was separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% acrylamide gels, transferred to a polyvinylidine difluoride membrane and then blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline. Membrane was subsequently incubated with a 1:1000 dilution of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), iNOS, PKG, phospho-ERK1/2, calcineurin A and NFATc3 antibodies. Proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase conjugated second antibody (1:1000 dilution, Chemicon). The immunoreactive bands detected by chemiluminescence reagents (PerkinElmer Life Sciences Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) were developed by Hyperfilm (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA).

Calcineurin phosphatase activity assay

Calcineurin activity was measured using a calcineurin cellular assay kit plus (BIOMOL, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA; catalogue number AK-816) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, neonatal rat ventricular myocytes were collected in 400 µL of lysis buffer (50 mmol·L−1 Tris, pH 7.5, 0.1 mmol·L−1 EDTA, 0.1 mmol·L−1 EGTA, 1 mmol·L−1 dithiothreitol, 0.2% Nonidet P-40). Free phosphate was removed by passing the lysates through a desalting column before assaying. The RII phosphopeptide was used as a specific substrate for calcineurin

Statistical analysis

The survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier analysis, and the log-rank test was used to detect any significant difference between survival curves. The values of other parameters were expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical significance was estimated by Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance (anova) followed by Dunnett's t-test. A P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Drugs

Isoprenaline and L-NNA were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). KMUP-1 was synthesized in our laboratory and was dissolved in normal saline or water. Anti-eNOS and ERK1/2 antibodies were obtained from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (Lake Placid, New York, NY, USA); anti-PKG antibodies were purchased from Calbiochem Co. (San Diego, CA, USA); anti-iNOS, calcineurin A and β-actin antibodies were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Inc.; Anti-phospho ERK1/2 antibody was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA); anti-NFATc3 antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). All other reagents used were of analytical grades or higher and were obtained from standard commercial sources.

Results

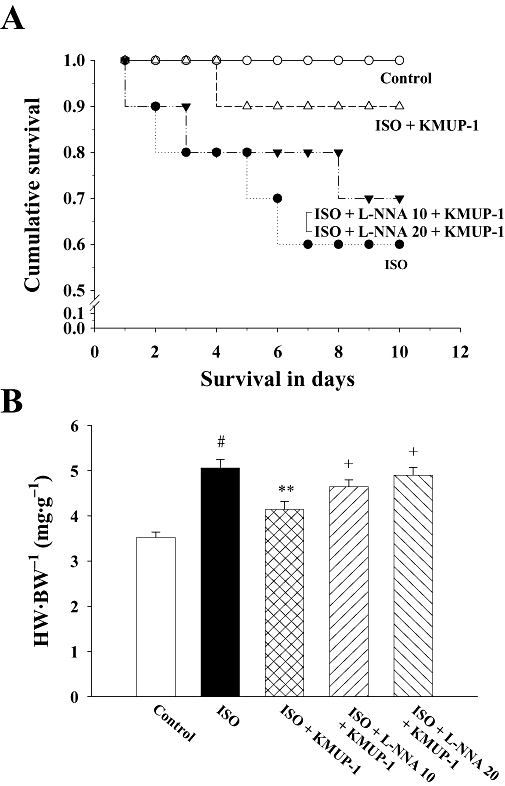

Effects of KMUP-1 on survival

Firstly we investigated whether KMUP-1 can improve the survival of rats after chronic treatment with ISO. As shown in Figure 1A, in the control group, survival was 100% until termination of the study (10 days). Compared with the control group, the survival rate in the ISO group was significantly decreased to 60% at the end of study; however, KMUP-1 preserved the survival rate in the ISO/KMUP-1 group to 90%. On the other hand, L-NNA tended to attenuate the protective effect of KMUP-1 by decreasing the survival rate from 90% to 70% in both the ISO/L-NNA 10/KMUP-1 and ISO/L-NNA 20/KMUP-1 groups; however, the differences were not significant.

Figure 1.

Effects of KMUP-1 on the survival rate (A) and heart weight to body weight ratio (B) in rats. #P < 0.05 versus control group; **P < 0.01 versus ISO group; +P < 0.05 versus ISO/KMUP-1 group. HW/BW, heart weight/body weight; ISO, isoprenaline; L-NNA, Nω-nitro-L-arginine.

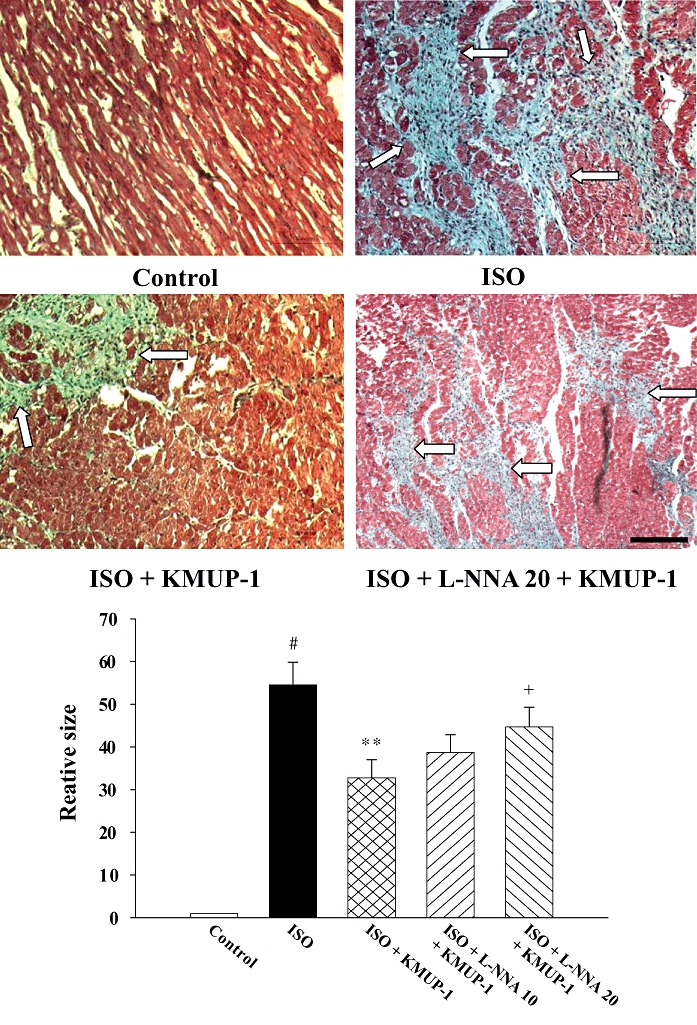

Effects on cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis

We further investigated the anti-hypertrophic and anti-fibrotic effects of KMUP-1. Figure 1B shows that ISO caused cardiac hypertrophy, indicated by an increased heart weight/body weight ratio. The hypertrophy was attenuated by simultaneous administration of KMUP-1. The anti-hypertrophic effect of KMUP-1 was blocked by L-NNA, as shown in both ISO/L-NNA 10/KMUP-1 and ISO/L-NNA 20/KMUP-1 groups, in a dose-dependent manner. Figure 2 shows that ISO caused significant cardiac fibrosis. Similarly, the fibrosis was attenuated by pretreatment with KMUP-1, and this anti-fibrotic effect of KMUP-1 was inhibited by L-NNA.

Figure 2.

Effects of KMUP-1 on cardiac fibrosis. Representative photomicrographs of heart slices dyed with Masson's trichrome stain (original magnification ×100) were shown with white arrows indicating fibrotic tissue. Quantification of fibrotic area was shown in the bottom panel. Data are shown as mean ± SE. #P < 0.05 versus control group; **P < 0.01 versus ISO group; +P < 0.05 versus ISO/KMUP-1 group. The size of the bar is 100 µm. ISO, isoprenaline; L-NNA, Nω-nitro-L-arginine.

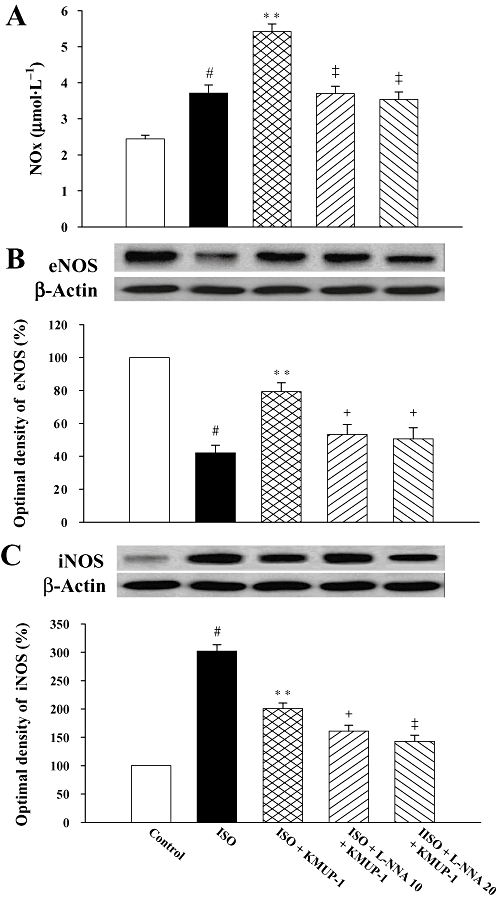

Effects of KMUP-1 on plasma NOx (nitrite/nitrate) and expression of cardiac eNOS and iNOS

Endogenous NO was found to be an important negative modulator for the hypertrophic responses. Therefore, we next investigated the effects of KMUP-1 on the endogenous NO system. As shown in Figure 3A, plasma NOx was increased by ISO when compared with control and was further increased by pretreatment with KMUP-1 when compared with the ISO group. The NOx-enhancing effect of KMUP-1 was blocked by L-NNA.

Figure 3.

Effects of KMUP-1 on serum nitric oxide (NOx) content and protein expression of cardiac eNOS and iNOS. The NOx production was quantified by measurements of nitrite and nitrate in rat serum (A). Effects of KMUP-1 on eNOS (B) and iNOS (C) protein expression in rat hearts were determined by Western blot analysis and densitometry. #P < 0.05 versus control group; **P < 0.01 versus ISO group; + P < 0.05, ‡P < 0.01 versus ISO/KMUP-1 group. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; ISO, isoprenaline; L-NNA, Nω-nitro-L-arginine.

The expression of eNOS and iNOS in rat hearts is shown in Figure 3B and C respectively. In heart tissues, ISO decreased eNOS expression and increased iNOS expression. However, pretreatment with KMUP-1 resulted in an up-regulation of eNOS expression and down-regulation of iNOS (P < 0.01 vs. ISO group). L-NNA significantly decreased the concentrations of both eNOS and iNOS.

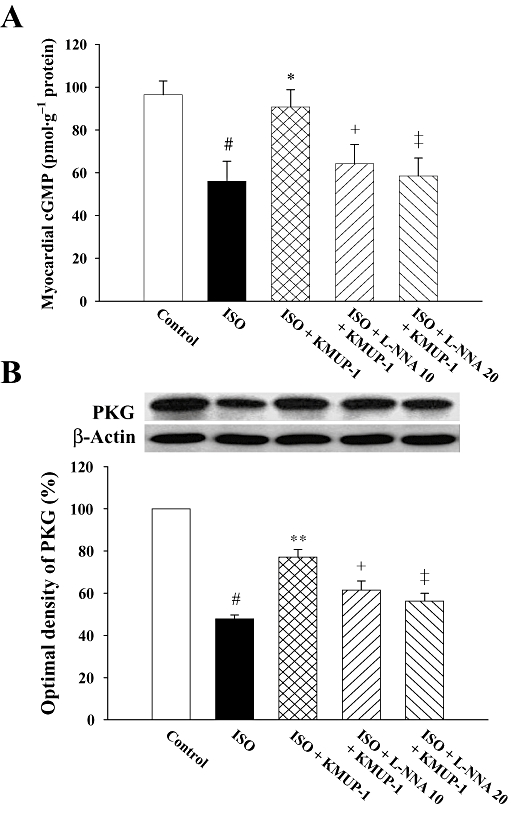

Effects of KMUP-1 on cGMP and PKG in rat hearts

We then investigated how KMUP-1 affected myocardial cGMP and PKG, the second messenger of NO and downstream cGMP-dependent protein kinase respectively. ISO decreased cardiac cGMP and PKG concentrations as shown in Figure 4A and B. Pretreatment with KMUP-1 increased both cGMP and PKG concentrations when compared with ISO alone. These effects of KMUP-1 on cGMP and PKG were both attenuated by L-NNA.

Figure 4.

Effects of KMUP-1 on levels of cGMP (A) and PKG (B) protein expression in rat hearts, determined by Western blot analysis and densitometry. #P < 0.05 versus control group; **P < 0.01 versus ISO group; +P < 0.05, ‡P < 0.01 versus ISO/KMUP-1 group. cGMP, guanosine 3′5′-cyclic monophosphate; ISO, isoprenaline; L-NNA, Nω-nitro-L-arginine; PKG, protein kinase G.

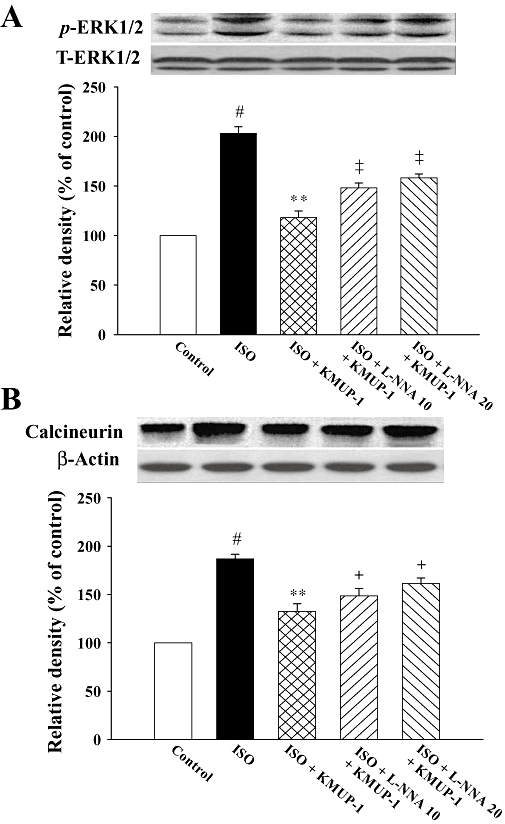

Effects of KMUP-1 on activation of ERK1/2 and calcineurin A in rat hearts

Activation of phosphate ERK1/2 and calcineurin A can both contribute to cardiac hypertrophy. Accordingly, we next examined whether KMUP-1 affected the signalling of these two pathways. As shown in Figure 5, ISO significantly activated the signalling of both ERK1/2 and calcineurin A pathways. Pretreatment with KMUP-1 blocked the activation of these two pathways induced by ISO, and these effects of KMUP-1 were attenuated by L-NNA in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 5.

Effects of KMUP-1 on the activation of calcineurin A (A) and ERK1/2 (B) protein expression in rat hearts determined by Western blot analysis and densitometry. #P < 0.05 versus control group; **P < 0.01 versus ISO group; +P < 0.05, ‡P < 0.01 versus ISO/KMUP-1 group. ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; ISO, isoprenaline; L-NNA, Nω-nitro-L-arginine.

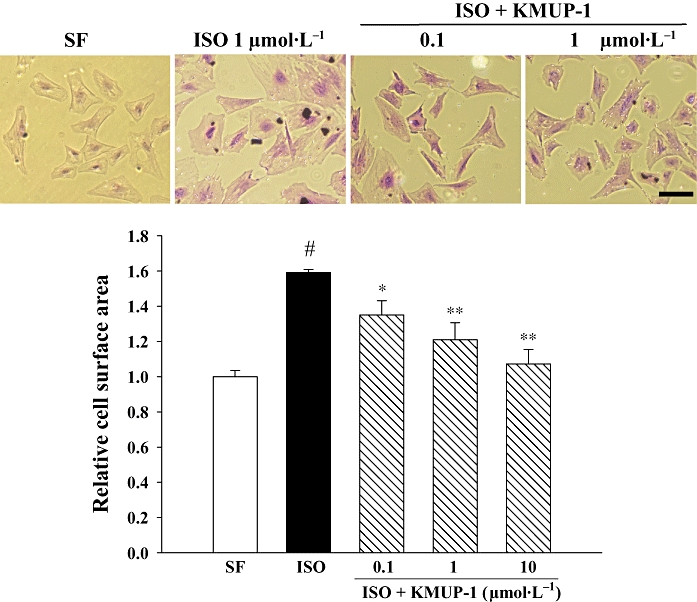

Effects of KMUP-1 on isoprenaline-induced hypertrophy of cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes

Exposure of neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes to ISO (1 µmol·L−1) for 48 h resulted in a robust hypertrophic response as evidenced by significant increases in cell surface area. When KMUP-1 (0.1–10 µmol·L−1) was given 1 h before ISO treatment, the ISO-induced cellular hypertrophy was significantly inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of KMUP-1 on isoprenaline (ISO)-induced hypertrophy of neonatal rat cardiomocytes. Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with KMUP-1 (0.1, 1 and 10 µmol·L−1) for 1 h before addition of 1 µmol·L−1 ISO for 48 h. After being washed with phosphate-buffered saline, adherent cells were fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10 min. Cell surface area was determined by planimetry, and >100 cells were analysed per condition in six repeated experiments. #P < 0.05 versus serum-free (SF) group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus ISO group. The size of the bar is 100 µm.

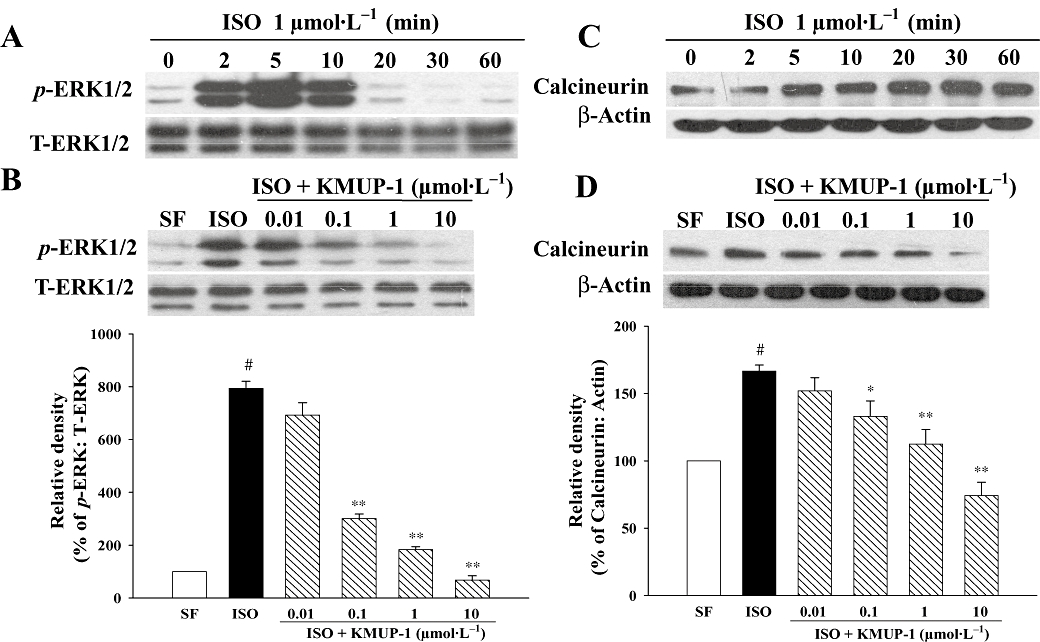

Effects of KMUP-1 on activations of ERK1/2 and calcineurin A in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes

As seen in Figure 7A, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes was induced by ISO (1 µmol·L−1) incubation within 2 min, peaking at 5 min. Pretreatment with KMUP-1 for 1 h inhibited ISO-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 7B). Similarly, ISO induced the expression of calcineurin A in cardiomyocytes (Figure 7C), peaking at 30 min, whereas pretreatment with KMUP-1 attenuated these effects dose-dependently (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Effects of KMUP-1 on ISO-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation and calcineurin A protein expression in neonatal rat cardiomocytes. Western blots show time courses of ISO-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (A) and calcineurin expression (C). Quiescent neonatal cardiomocytes were pretreated with different concentrations of KMUP-1, followed by incubation with ISO (1 µmol·L−1). KMUP-1 attenuated ISO-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (B) and calcineurin A activation (D). Representative Western blots and densitometric quantification of all experiments (n = 5) for each group are shown. #P < 0.05 versus serum-free (SF) group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus ISO group. ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; ISO, isoprenaline.

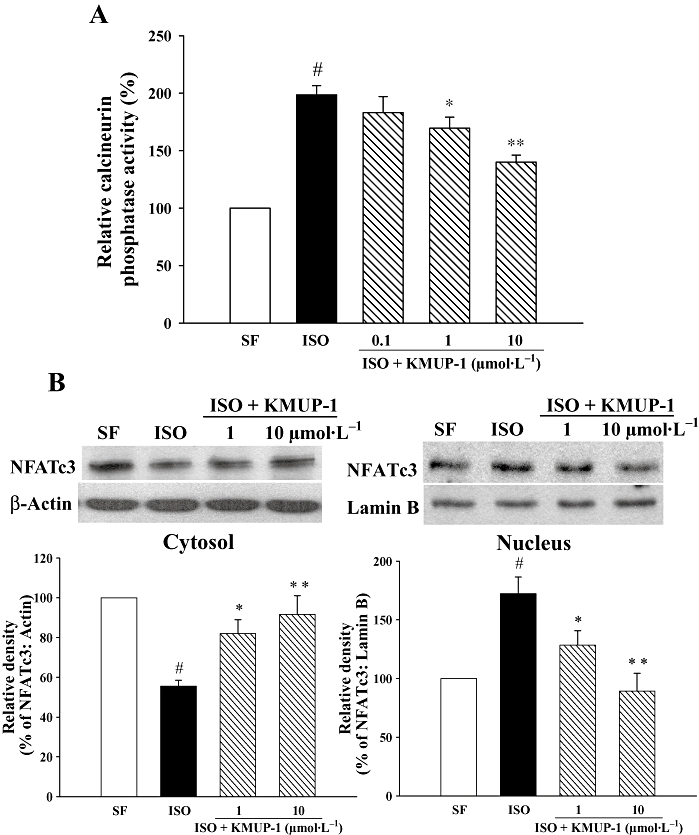

Effects of KMUP-1 on calcineurin activity and NFATc3 translocation in cultured neonatal cardiomocytes

To investigate effects of KMUP-1 on ISO-induced activation of calcineurin–NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T cell) signalling further, we examined calcineurin phosphatase activity and translocation of NFATc3, an important NFAT subtype involved in hypertrophic signalling (Wilkins et al., 2002). We first found that ISO conferred a twofold increase in calcineurin phosphatase activity (Figure 8A). However, the increase was significantly attenuated by KMUP-1.

Figure 8.

Effect of KMUP-1 on calcineurin activity and NFATc3 translocation in cardiomyocytes. Neonatal rat cardiomocytes were treated for 1 h in the presence or absence of KMUP-1, followed by incubation with ISO (1 µmol·L−1) for 24 h. (A) Cell lysates were subjected to calcineurin phosphatase activity assays (n = 3). (B) Immunoblotting studies on cytosolic and nuclear fractions of NFATc3 were performed separately. The quantifications of NFATc3 protein are shown in the bottom panels (n = 3). #P < 0.05 versus serum-free (SF) group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus ISO group. ISO, isoprenaline; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cell.

We then examined the translocation of NFATc3 from the cytosolic compartment to the nuclear compartment, by immunoblotting for NFATc3 using cytosolic and nuclear fractions separately in cardiomyocytes (Figure 8B). Our results demonstrate that ISO caused decreased cytosolic NFATc3 protein and increased nuclear NFATc3 protein in cardiomyocytes, suggesting that ISO induce the translocation of NFATc3 from cytosol into the nucleus. Similarly, the ISO-induced translocation was blocked by KMUP-1.

Discussion

The results from the present study indicate that KMUP-1, a novel xanthine-based derivative, can attenuate cardiac hypertrophic responses induced by ISO from physiological, morphological and molecular standpoints. We demonstrated that KMUP-1 improves the survival of rats treated with ISO. In addition, cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis and activation of hypertrophic signalling pathways (calcineurin A and ERK1/2) induced by ISO were all attenuated in rats pretreated with KMUP-1. Furthermore, KMUP-1 augmented the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway, and the cardioprotective effects of KMUP-1 were blunted by NOS inhibition. Taken together, these results indicate that the anti-hypertrophic effect of KMUP-1 is mediated, at least in part, by activation of NOS.

Emerging evidence suggests that the NO system plays an important role in the modulation of cardiac hypertrophy (Loke et al., 1999; Ozaki et al., 2002). The role of NO in heart failure is complex and remains controversial. In the present study, we tried to determine the role of the NO system in this animal model of cardiac hypertrophy and how KMUP-1 regulates the NO system in this model. Our results demonstrated that plasma NOx, an indirect indicator of total endogenous production of NO, was increased by ISO. However, KMUP-1 further increased the plasma concentration of NOx to a greater extent. Interestingly, we found that in heart tissue KMUP-1 increased eNOS and decreased iNO expression and so counteracted the discrepant expression of eNOS and iNOS induced by ISO. In addition, our results suggest that the increased endogenous production of NO in rats with ISO-induced cardiac hypertrophy was mainly caused by cardiac iNOS expression; whereas the greater increase of endogenous NO production induced by KMUP-1 might be primarily caused by cardiac eNOS expression.

The roles of eNOS and iNOS in pathological conditions of the heart are complex. However, recent studies have shown that NO may have beneficial or deleterious effects on myocardium, if derived from eNOS or iNOS respectively. For example, in chick embryonic cardiac myocytes, cytokine-induced expression of iNOS was accompanied by a depression of basal myocardial shortening caused by a reduction in cytolosic calcium transient (Kinugawa et al., 1997). In addition, the induction of iNOS in vitro resulted in myocardial apoptosis, partly through the generation of reactive oxygen species (Ing et al., 1999). Indeed, chronic cardiac-specific up-regulation of iNOS in transgenic mice led to increased production of peroxynitrite, bradyarrhythmia and sudden death, with associated cardiac fibrosis, hypertrophy and dilatation (Mungrue et al., 2002). On the other hand, in eNOS knockout mice, bradykinin-induced reduction of myocardial oxygen consumption was abolished (Loke et al., 1999). Recent studies also showed that overexpression of eNOS attenuates cardiac hypertrophy in mice (Ozaki et al., 2002) and that reduced eNOS activity contributes to the onset of myocardial hypertrophy and increased cytokine expression (Wenzel et al., 2007). Consistent with these studies, our results demonstrated effects of KMUP-1 in augmenting eNOS and decreasing iNOS protein, which were beneficial in the reduction of myocardial oxygen consumption, and thus offset cardiac hypertrophy and improved the survival.

A large body of emerging evidence supports a role for cGMP as a cardioprotective agent against hypertrophy. For example, NO-induced cGMP via the sGC receptor can block hypertrophy (Calderone et al., 1998). In addition, stimulation of adult cardiac myocytes with a cGMP analogue or natriuretic pepetides has the same anti-hypertrophic effect (Calderone et al., 1998; Rosenkranz et al., 2003). Conversely, disruption of cardiac guanylate cyclase-A gene caused cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy (Kishimoto et al., 2001). Precisely how increased cGMP production prevents cardiac hypertrophy has not been entirely elucidated but it probably involves cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG), a serine/threonine kinase activated by cGMP. PKG inhibits L-type Ca2+ channels thus reducing Ca2+ transient amplitude and blocking calcineurin-mediated activation of NFAT, a transcription factor that is obligatory for hypertrophy (Fiedler et al., 2002). Therefore, in the present study, increased cardiac cGMP and PKG with down-regulation of calcineurin/NFAT signalling caused by KMUP-1 explain how it can be the braking force against ISO-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Similar to our study, increased intracellular concentration of cGMP within cardiomyocytes induced by activation of atrial natriuretic peptide receptor in the mouse heart has been shown to convey protective effects against ISO-induced cardiac hypertrophy (Zahabi et al., 2003).

Because cGMP is the common second messenger of NO and natriuretic peptides, the anti-hypertrophic, vasodilatory and diuretic properties of natriuretic peptides have generated interest in the potential clinical use of natriuretic peptides. Of all the natriuretic peptides, human B-type natriuretic peptide (nesiritide) has been approved by the US FDA for the treatment of heart failure. However, a recent meta-analysis suggested that there may be some unappreciated safety issues (Aaronson and Sackner-Bernstein, 2006). Therefore, therapy targeted at the NO/cGMP pathway may be potentially better as an alternative strategy for the management of cardiac hypertrophy in the future. In the present study, we demonstrated that the cGMP-enhancing effect induced by KMUP-1 was inhibited by L-NNA in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that the effect of KMUP-1 on cGMP is mediated by activation of the NO pathway rather than natriuretic peptides.

Similar to calcineurin A, the ERK1/2 plays an important role in the hypertrophic signalling. Indeed, ERK1/2 is activated in response to almost every known hypertrophic agonist (Bueno and Molkentin, 2002) and is itself a contributor to hypertrophy (Bueno et al., 2000). In the present study, we also examined the effect of KMUP-1 on ERK1/2 and found that the activation of ERK1/2 by ISO was blocked by KMUP-1. However, the deactivating effect of KMUP-1 on ERK1/2, similar to the effect on calcineurin A, was attenuated but not abolished by L-NNA, suggesting that some pathway other than NOS activation may also be targeted by KMUP-1 and warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, KMUP-1 attenuates ISO-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rats. These effects are mediated, at least in part, by NOS activation. This novel agent that targets the NO/cGMP pathway has potential for use in the prevention of cardiac hypertrophy and associated cardiovascular morbidity.

Acknowledgments

The present work was supported by research grants NSC-95-2314-B-037-089-MY3 and NSC-96-2628-B-037-008-MY3 from the National Science Council, Taiwan. We would also like to thank Ms Li-Ying Chen for technical assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- cGMP

guanosine 3′5′-cyclic monophosphate

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- ISO

isoprenaline

- L-NNA

Nω-nitro-L-arginine

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T cell

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- PKG

protein kinase G

Conflict of interest

None of our authors have conflicts of interests.

References

- Aaronson KD, Sackner-Bernstein J. Risk of death associated with nesiritide in patients with acutely decompensated heart failure. JAMA. 2006;296:1465–1466. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.12.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno OF, Molkentin JD. Involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 in cardiac hypertrophy and cell death. Circ Res. 2002;91:776–781. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000038488.38975.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno OF, De Windt LJ, Tymitz KM, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Klevitsky R, et al. The MEK1-ERK1/2 signaling pathway promotes compensated cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 2000;19:6341–6350. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderone A, Thaik CM, Takahashi N, Chang DL, Colucci WS. Nitric oxide, atrial natriuretic peptide, and cyclic GMP inhibit the growth-promoting effects of norepinephrine in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:812–818. doi: 10.1172/JCI119883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler B, Wollert KC. Interference of antihypertrophic molecules and signaling pathways with the Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT cascade in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler B, Lohmann SM, Smolenski A, Linnemuller S, Pieske B, Schroder F, et al. Inhibition of calcineurin-NFAT hypertrophy signaling by cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I in cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11363–11368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162100799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey N, Katus HA, Olson EN, Hill JA. Hypertrophy of the heart: a new therapeutic target? Circulation. 2004;109:1580–1589. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000120390.68287.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan MA, Ketat AF. Sildenafil citrate increases myocardial cGMP content in rat heart, decreases its hypertrophic response to isoproterenol and decreases myocardial leak of creatine kinase and troponin T. BMC Pharmacol. 2005;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ing DJ, Zang J, Dzau VJ, Webster KA, Bishopric NH. Modulation of cytokine-induced cardiac myocyte apoptosis by nitric oxide, Bak, and Bcl-x. Circ Res. 1999;84:21–33. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinugawa KI, Kohmoto O, Yao A, Serizawa T, Takahashi T. Cardiac inducible nitric oxide synthase negatively modulates myocardial function in cultured rat myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H35–H47. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.1.H35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto I, Rossi K, Garbers DL. A genetic model provides evidence that the receptor for atrial natriuretic peptide (guanylyl cyclase-A) inhibits cardiac ventricular myocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2703–2706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051625598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1561–1566. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005313222203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin RJ, Wu BN, Lo YC, Shen KP, Lin YT, Huang CH, et al. KMUP-1 relaxes rabbit corpus cavernosum smooth muscle in vitro and in vivo: involvement of cyclic GMP and K+ channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:1159–1166. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CM, Lo YC, Wu BN, Wu WJ, Chou YH, Huang CH, et al. cGMP-enhancing- and alpha1A/alpha1D-adrenoceptor blockade-derived inhibition of Rho-kinase by KMUP-1 provides optimal prostate relaxation and epithelial cell anti-proliferation efficacy. Prostate. 2007;67:1397–1410. doi: 10.1002/pros.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CM, Lo YC, Tai MH, Wu BN, Wu WJ, Chou YH, et al. Piperazine-designed alpha 1A/alpha 1D-adrenoceptor blocker KMUP-1 and doxazosin provide down-regulation of androgen receptor and PSA in prostatic LNCaP cells growth and specifically in xenografts. Prostate. 2009;69:610–623. doi: 10.1002/pros.20919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loke KE, McConnell PI, Tuzman JM, Shesely EG, Smith CJ, Stackpole CJ, et al. Endogenous endothelial nitric oxide synthase-derived nitric oxide is a physiological regulator of myocardial oxygen consumption. Circ Res. 1999;84:840–845. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.7.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin JD. Calcineurin-NFAT signaling regulates the cardiac hypertrophic response in coordination with the MAPKs. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisco C, Zebrowski D, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. β-Adrenergic cardiac hypertrophy is mediated primarily by the β1-subtype in rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:561–573. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungrue IN, Gros R, You X, Pirani A, Azad A, Csont T, et al. Cardiomyocyte overexpression of iNOS in mice results in peroxynitrite generation, heart block, and sudden death. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:735–743. doi: 10.1172/JCI13265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki M, Kawashima S, Yamashita T, Hirase T, Ohashi Y, Inoue N, et al. Overexpression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase attenuates cardiac hypertrophy induced by chronic isoproterenol infusion. Circ J. 2002;66:851–856. doi: 10.1253/circj.66.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos JW. The regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in mammalian cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2707–2719. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz AC, Woods RL, Dusting GJ, Ritchie RH. Antihypertrophic actions of the natriuretic peptides in adult rat cardiomyocytes: importance of cyclic GMP. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:515–522. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00667-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoshima J, Izumo S. The cellular and molecular response of cardiac myocytes to mechanical stress. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:551–571. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto E, Champion HC, Li M, Belardi D, Ren S, Rodriguez ER, et al. Chronic inhibition of cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase 5A prevents and reverses cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2005;11:214–222. doi: 10.1038/nm1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel S, Rohde C, Wingerning S, Roth J, Kojda G, Schluter KD. Lack of endothelial nitric oxide synthase-derived nitric oxide formation favors hypertrophy in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes. Hypertension. 2007;49:193–200. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000250468.02084.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins BJ, De Windt LJ, Bueno OF, Braz JC, Glascock BJ, Kimball TF, et al. Targeted disruption of NFATc3, but not NFATc4, reveals an intrinsic defect in calcineurin-mediated cardiac hypertrophic growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7603–7613. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7603-7613.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu BN, Lin RJ, Lin CY, Shen KP, Chiang LC, Chen IJ. A xanthine-based KMUP-1 with cyclic GMP enhancing and K+ channels opening activities in rat aortic smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:265–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu BN, Lin RJ, Lo YC, Shen KP, Wang CC, Lin YT, et al. KMUP-1, a xanthine derivative, induces relaxation of guinea-pig isolated trachea: the role of the epithelium, cyclic nucleotides and K+ channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:1105–1114. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu BN, Chen CW, Liou SF, Yeh JL, Chung HH, Chen IJ. Inhibition of proinflammatory tumor necrosis factor-{alpha}-induced inducible nitric-oxide synthase by xanthine-based 7-[2-[4-(2-chlorobenzene)piperazinyl]ethyl]-1,3-dimethylxanthine (KMUP-1) and 7-[2-[4-(4-nitrobenzene)piperazinyl]ethyl]-1, 3-dimethylxanthine (KMUP-3) in rat trachea: The involvement of soluble guanylate cyclase and protein kinase G. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:977–985. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.024919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JR, Liou SF, Lin SW, Chai CY, Dai ZK, Liang JC, et al. Lercanidipine inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointimal formation via reducing intracellular reactive oxygen species and inactivating Ras-ERK1/2 signaling. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahabi A, Picard S, Fortin N, Reudelhuber TL, Deschepper CF. Expression of constitutively active guanylate cyclase in cardiomyocytes inhibits the hypertrophic effects of isoproterenol and aortic constriction on mouse hearts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47694–47699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]