Abstract

We have analyzed the role of actin polymerization in retinoic acid (RA)-induced HoxB transcription, which is mediated by the HoxB regulator Prep1. RA induction of the HoxB genes can be prevented by the inhibition of actin polymerization. Importantly, inhibition of actin polymerization specifically affects the transcription of inducible Hox genes, but not that of their transcriptional regulators, the RARs, nor of constitutively expressed, nor of actively transcribed Hox genes. RA treatment induces the recruitment to the HoxB2 gene enhancer of a complex composed of “elongating” RNAPII, Prep1, β-actin, and N-WASP as well as the accessory splicing components p54Nrb and PSF. We show that inhibition of actin polymerization prevents such recruitment. We conclude that inducible Hox genes are selectively sensitive to the inhibition of actin polymerization and that actin polymerization is required for the assembly of a transcription complex on the regulatory region of the Hox genes.

INTRODUCTION

The presence of β-actin in the nucleus was documented for the first time many years ago (Egly et al., 1984; Scheer et al., 1984), but the connection between β-actin and gene transcription has only recently been demonstrated (Olave et al., 2002; Pederson and Aebi, 2002; Fomproix and Percipalle, 2004; Grummt, 2006; Jockusch et al., 2006; Percipalle and Visa, 2006; Obrdlik et al., 2007). Nuclear β-actin associates with components of the ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes (Olave et al., 2002; Bettinger et al., 2004), with RNP particles (Percipalle and Visa, 2006), and with the three RNA polymerases in the eukaryotic cell nucleus, both in vitro and in vivo (Hu et al., 2004; Philimonenko et al., 2004; Kukalev et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2006). The above studies have shown that nuclear actin is a component of large protein complexes that include RNA polymerases, transcription elongation factors, and accessory splicing factors that can be recruited to the RNAPII carboxy terminal domain and hence to promoters.

Interestingly, a number of studies have shown the nuclear presence of proteins that stimulate actin polymerization, e.g., N-WASP (neuronal Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Protein) and Arp2/3 (Wu et al., 2006; Yoo et al., 2007), raising the possibility that actin polymerization may occur in this cellular compartment. The observation in a recent FRAP analysis that ∼20% of the total nuclear actin pool is in the polymeric state supports this idea (McDonald et al., 2006). Importantly transcription is affected by the down-regulation of N-WASP or by inhibiting actin polymerization either through the expression of polymerization-deficient actin mutants or by using high concentrations of specific drugs, such as cytochalasin D (CytD) or latrunculin A (LatA; McDonald et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006; Yoo et al., 2007; Ye et al., 2008). These observations indicate that actin polymerization is necessary for gene transcription. However, it is not known whether all genes are equally sensitive to inhibition of actin polymerization. Also it is not known whether actin polymerization is required for the recruitment of active transcription complexes to transcription regulatory sites. This article deals with the role of actin in the induction of Hox gene transcription by retinoic acid (RA). Cell fate–determining clustered Hox genes are expressed colinearly in the same order as their location on the genome, generating anterior-to-posterior identities (Krumlauf, 1994). Several lines of evidence have demonstrated the importance of RA receptors (RARs) for patterning and basal expression of Hox genes in the vertebrate neural tube (Marshall et al., 1994, 1996; Gould et al., 1998; Dupe et al., 1999). However, expression of anterior HoxB genes also depends on an auto-regulatory circuit involving the HoxB1 protein and the Prep1–Pbx1 complex (Marshall et al., 1996; Maconochie et al., 1997; Dupe et al., 1999; Jacobs et al., 1999; Ryoo et al., 1999; Ferretti et al., 2000, 2005; Huang et al., 2002). Prep1 and Pbx1 are essential genes in embryonic development (Selleri et al., 2001; Waskiewicz et al., 2002; Deflorian et al., 2004; Penkov et al., 2005; Ferretti et al., 2006; Di Rosa et al., 2007). Unlike monomeric Prep1 and Pbx1, dimeric Prep1–Pbx1 complexes bind DNA and interact with HoxB1 to activate HoxB1 and HoxB2 transcription (Berthelsen et al., 1998; Ryoo et al., 1999; Ferretti et al., 2000, 2005; Huang et al., 2002).

Colinear transcription can be reproduced in the NT2-D1 teratocarcinoma cell line in which RA induces multilineage differentiation. In these cells, time-course experiments show that the expression of the HoxB cluster initiates at the 3′ end with the HoxB1 gene and time-dependently proceeds toward the 5′ end, transcribing all genes colinearly with their chromosomal location (Simeone et al., 1990).

We have recently shown that Prep1 specifically copurifies and coprecipitates not only with its dimeric partner Pbx1 and with RNAPII, but also with nuclear (but not cytoplasmic) β-actin (Diaz et al., 2007a). As the Prep1 complex is required for transcriptional induction of the HoxB genes (Ferretti et al., 2000, 2005; Waskiewicz et al., 2002; Deflorian et al., 2004), the association of Prep1 to β-actin prompted us to analyze the role of actin polymerization in HoxB transcriptional induction. Here, we report that three different approaches to block actin polymerization: the use of CytD or LatA inhibitors, down-regulation of the actin polymerization stimulator N-WASP, and a dominant-negative actin mutant—all inhibit the induction of HoxB genes by RA. Our studies with CytD demonstrate that actin polymerization is required for the colinear expression of HoxB genes at the time of transcription initiation. Importantly, we show that the inhibition of actin polymerization has no effect on genes whose transcription has already started, indicating that induced genes are more sensitive to β-actin polymerization inhibition than constitutively transcribed genes. Although CytD has no effect on the expression of RARs, actin polymerization is required for the RA-induced recruitment of a number of proteins to the regulatory regions of the HoxB2 gene, such as Prep1, β-actin, the elongating form of the RNAPII phosphorylated in serine 2 of the carboxy-terminal domain (RNAPII-S2p), N-WASP, and the p54/Nrb–PSF complex that was previously shown to interact with N-WASP (Wu et al., 2006). Treatment with CytD totally blocks the recruitment of these proteins to the regulatory region of HoxB2, supporting a direct functional role of actin polymerization in the induction of the HoxB cluster.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Treatments

Human NT2-D1 cells were grown in DMEM (Cambrex BioScience, Milan, Italy) and used at 70% confluence. Trans-RA was from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy). Controls were treated with 0.1% DMSO. CytD was from EMD Biosciences (Darmstadt, Germany).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: monoclonal anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich); polyclonal anti-total RNAPII, anti-RNAPII-S2p, and anti-Pbx1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); anti-Prep-1 polyclonal antibody (Berthelsen et al., 1998) and CH12.2 monoclonal were prepared by standard techniques. Polyclonal anti-N-WASP was published previously (Rohatgi et al., 1999). Polyclonal anti-PSF and monoclonal anti-p54/Nrb antibodies were kind gifts of Drs. A. Krainer (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY) and J. Patton (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), respectively.

RNA and Protein Extraction, Coimmunoprecipitation, Immunoblotting, and Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

RNA was extracted with Qiagen mini columns and RNeasy mini kit-250 (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Nuclear extracts were prepared as described (Dignam et al., 1983).

Coimmunoprecipitations were performed with protein G-Sepharose (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA). Nuclear proteins were diluted in 10 mM Tris, pH 8, 0.2% NP-40, and 150 mM NaCl, precleared, incubated with 5 μg antibodies overnight at 4°C, and pulled down with protein G.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) for Prep1–Pbx1 was carried out with the 32P-labeled O1 oligonucleotide 5′CACCTGAGAGTGACAGAAGGAGGCAGGGAG3′ (Berthelsen et al., 1998).

N-WASP Silencing

hN-WASP-1 (CGGCAAGAAAUGUGUGACUAUGUCU; Invitrogen, Milan, Italy) was transfected in NT2-D1 cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer. At 24 h cells were passed to new medium with RA (1 μM) or DMSO (control) and grown for 16 h. We also used the SC36006 oligonucleotide from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, which totally abolished N-WASP expression.

PCR and Real-Time PCR

RNA, 1 μg, oligodT, 0.5 μg, and SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) were used. Primers were as follows: GADPH: ACCACCTGGTGCTCAGTGTA (sense) and ACATCATCCCTGCCTCTACTG (antisense); HoxB1: GCATCTCCAGCTGCCTCCTT (antisense) and CCTTCTTAGAGTACCCACTCTG (sense); and HoxB2: AGTGGAATTCCTTCTCCAGTTCC (antisense) and TCCTCCTTTCGAGCAAACCTTCC (sense).

cDNA, 5 ng, was amplified (in triplicate) with TaqMan PCR Mastermix and TaqMan Gene expression assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and measured in the ABI/Prism 7900 HT Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems), using a pre-PCR step of 10 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 60 s at 60°C. RNA without reverse transcriptase was used as negative control. 18S rRNA and GAPDH were used as standards. Proprietary primers from Applied Biosystems were used.

For real-time PCR of the HoxB2 expression levels in actin mutant transfections, the reverse-transcribed RNA was amplified in a light cycler (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) using a FastStart DNA mix SYBR Green I kit (Roche). PCR conditions were as follows: for HoxB2 mRNA: denaturation and DNA polymerase activation step, 95°C for 10 min; second denaturation step, 95°C for 15 s; annealing step, 56°C for 6 s; and extension step, 72°C for 20 s. GAPDH conditions were as follows: first denaturation and DNA polymerase activation step, 95°C for 10 min; second denaturation step, 95°C for 15 s; annealing step, 57°C for 6 s; extension step, 72°C for 20 s. The amount of HoxB2 mRNA was normalized to GAPDH mRNA. The primers are reported above.

Pyrene Actin Polymerization Assay

Nuclear extracts from NT2-D1 cells were dialyzed against G buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 0.2 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM CaCl2, and wt/vol, 0.01% NaN3) for 4 h. Actin polymerization was measured by the increase in fluorescence of 10% pyrenil-labeled actin, as described (Disanza et al., 2006) after addition of 0.1 M KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.2 mM EGTA to a solution of Ca-ATP-G-actin (2 μM-10% pyrene) containing 80 μl of extract, and 10 μg of glutathione S-transferase (GST) or GST-vascular cell adhesion (VCA) fusion protein. Purified Arp 2/3 complex (10 nM), supplemented with GST or GST-VCA, was used as internal control.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Chromatin from p-formaldehyde (1%) cross-linked cells was prepared and sonicated as described (Ferrai et al., 2007). Aliquots were immunoprecipitated overnight with 1 μg of antibody, and DNA was extracted after reversion of cross-linking by heating at 65°C for 5 h. Purified immunoprecipitated DNA was quantitated by QT-PCR in a light cycler (Roche): denaturation and DNA polymerase activation, 95°C for 10 min; denaturation, 95°C, 15 s; annealing, 54°C (HoxB2 enhancer) and 60°C (intergenic region) for 6 s; extension, 72°C for 20 s. The relative enrichment was determined by calculating the ratio of immunoprecipitated DNA to input DNA.

The following primers were used: primers for HoxB2 Enhancer: Fw-TGGCTGTTCGCTCTGCTTTCC; Rev-AGGGCACAAGACTCTGAGCC; primers for the uPA intergenic region: Fw-CAGTAATCTGGCCTTGCCTTTCC; Rev-GAGGAATCGAGAGGCTTGTAAATTC.

RESULTS

Actin-depolymerizing Drugs Block HoxB Induction

We analyzed the role of actin polymerization in RA-induced transcription of the HoxB gene cluster in NT2-D1 cells. We measured the levels of various HoxB mRNAs by real-time PCR at different times after RA (1 μM) addition and explored the effect of the actin-capping agent CytD (100 nM). Table 1 shows that, in the absence of CytD, HoxB1, and HoxB2 mRNAs were already induced 16 h after RA addition, whereas HoxB3 and HoxB6 were induced at 48 and 72 h, respectively (as expected) (Simeone et al., 1990). CytD was added to the cells 16 or 24 h before mRNA level determination (i.e., at t = 0 for the 16-h measurement, at t = 24 h after RA for the 48-h measurement, and at t = 48 h after RA for the 72-h measurement; see Table 1). A scheme of the experiment is presented in Supplemental Figure S1. When added with RA at t = 0, CytD completely inhibited HoxB1 and HoxB2 induction, as measured at 16 h (Table 1; raw data obtained by real-time PCR are shown in Supplemental Figure S2). Transcription of HoxB3 and HoxB6, which were induced at 48 or 72 h, respectively, was inhibited significantly when CytD was added 24 or 48 h after RA, respectively (Table 1). However, when CytD was administered after transcription of HoxB1, HoxB2, or HoxB3 had already started, i.e., at 24 or 48 h after RA, respectively, no transcriptional inhibition was observed (Table 1). These results suggest that, at the concentration used (100 nM), CytD inhibits the initiation of HoxB transcription, but that it does not affect transcription that has already initiated. Consequently, genes may be differentially sensitive to CytD, depending on their expression state.

Table 1.

CytD inhibits RA-induced Hox gene expression in NT2–1 cells

| Genes | Control0 h | RA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 h | 16 h + CytD | 48 h | 48 h + CytD | 72 h | 72 h + CytD | ||

| HoxB1 | 0 | 1.0 (1.22–0.82) | 0.177 (0.21–0.15) | 1.0 (1.07–0.94) | 0.996 (1.02–0.97) | 1.0 (1.22–0.821) | 1.07 (1.25–0.925) |

| HoxB2 | 0 | 1.0 (1.052–0.95) | 0.05 (0.061–0.041) | 1.0 (1.12–0.89) | 1.102 (1.12–1.08) | 1.0 (0.876–1,14) | 1.154 (1.095–1.22) |

| HoxB3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 (1.19–0.84) | 0.5 (0.62–0.40) | 1.0 (1.2–0-83) | 0.8 (0.93–0.69) |

| HoxB6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 (1.13–0.89) | 0.377 (0.172–0.83) |

The data are the average of triplicate quantitative PCR experiment performed at least twice. Time in hours (h) refers to the exposure to 1 μM RA. When present, CytD (100 nM) was added before the measurement, i.e., at t = 0 for the 16-h, at t = 24 for the 48-h, and at t = 48 for the 72-h measurement. The level of mRNA expression after induction (in the absence of CytD) is set equal to 1.0; the values in parentheses represent the confidence interval at 95%.

We also measured the CytD sensitivity of other basally expressed or inducible genes after RA treatment (Table 2). The expression of three RA-inducible genes, HoxA1, HoxA2, and Meis1 was not affected by CytD, confirming that not all inducible genes are necessarily inhibited by 100 nM CytD. Eps8, which is constitutively expressed independently of RA, likewise, was not affected by CytD (Table 2).

Table 2.

CytD does not inhibit transcription of inducible HoxA and Meis1 genes or of constitutively expressed Eps8 gene in NT2-D1 cells

| Gene | Untr. | Untr. CytD at t = 0 | RA 16 h | RA 16 h CytD at t = 0 | RA 48 h | RA 48 h CytD t = 24 h | RA 72 h | RA 72 h CytD t = 48 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HoxA1 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 (0.94–1.06) | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | 1.0 (1.13–0.88) | 0.946 (1.16–0.77) | ND | ND |

| HoxA2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND | ND | ||

| Meis1 | 0.1 (0.114–0.1) | 0.15 (0.12–0.20) | 0 | 0 | 1.0 (1.25–0.8) | 0.90 (0.98–0.82) | ND | ND |

| Eps8a | 1.33 (1.6–1.1) | ND | ND | ND | 1.0 (1.22–0.82) | 0.885 (1.02–0.77) | ||

| Eps8a | 0.762 (0.65–0.9) | ND | ND | ND | 1.0 (0.79–1.27) | 0.92 (0.79–1.06) |

The data are the average of triplicate quantitative PCR experiment performed at least twice. Time in hours (h) refers to the exposure to 1 μM RA. When present, CytD (100 nM) was added before the measurement, i.e., at t = 0 for the 16-h, at t = 24 for the 48-h, and at t = 48 for the 72-h measurement. The level of mRNA expression after induction (in the absence of CytD) is always set equal to 1.0; the values in parentheses represent the confidence interval at 95%. Untr., untranslated.

a Eps8 was measured in two experiments, with different times of induction and CytD addition.

We used another inhibitor of actin polymerization, LatA, and measured HoxB3 mRNA levels 48 h after RA addition to confirm our data. Indeed, LatA inhibited HoxB3 transcription by 75% (data obtained by Q-PCR, Supplemental Table S1). For reasons not fully understood, the effect of LatA on HoxB1 and HoxB2 early expression was not as strong as CytD. Similarly to CytD, LatA had no effect on the transcription of HoxB1 and HoxB2 after their expression had been induced, but inhibited well HoxB3 and HoxB6 expression. We also compared the effects of 100 nM CytD to that of two F-actin–stabilizing drugs, jasplakinolide and phalloidin, on the RA-induction of HoxB1 and HoxB2 by performing RT-PCR at 24 h (drugs added together with RA). At the concentrations used, these two drugs had a slight stimulatory effect on HoxB1 and HoxB2 transcription (Supplemental Figure S3). Overall, our data support the interpretation that the CytD-dependent inhibition of transcription is due to a block in actin polymerization.

The inhibition of actin polymerization can certainly also affect the properties of cells, for example, neuronal differentiation after RA addition. However, the effect of CytD on HoxB expression seems to be specific and we believe is unlikely to be secondary to changes in cell morphology or cell division. In fact, both CytD or LatA do not drastically change the cell shape (even at the low concentrations used) and have no effect on NT2-D1 cell division (data not shown).

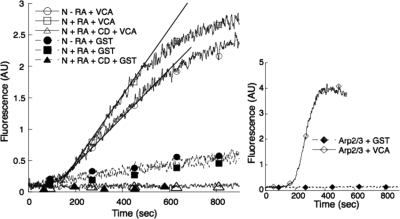

N-WASP Down-Regulation Inhibits the Expression of the HoxB Cluster

We next tested the effect of RA on actin polymerization mediated by the ARP2/3 complex. N-WASP is an effector protein for actin polymerization that is also present in the nucleus (Wu et al., 2006). The WCA domain of N-WASP can promote actin nucleation and its subsequent polymerization by simultaneously associating with the ARP2/3 complex and monomeric actin present in the nuclear extracts. The formation of this tripartite unit allows the thermodynamic barrier of actin nucleation to be overcome (Pantaloni et al., 2000, 2001). We reasoned that the addition of RA may facilitate the formation of the actin–ARP2/3 complex, thus accelerating the polymerization of actin in the presence of exogenous WCA. We thus incubated purified C-terminal WCA domain of N-WASP with pyrenil-labeled actin and nuclear extract of cells treated or not with RA. Remarkably, the rate of N-WASP–dependent actin polymerization was increased in nuclear extracts of RA-treated cells in a CytD-dependent manner (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

RA increases the polymerization rate in NT2-D1 nuclear extracts, in vitro. Nuclear extracts from NT2-D1 cells were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Left, equal amounts of extracts were mixed with GST or GST-VCA (10 μg), as indicated, and subjected to the pyrene actin polymerization assay. The lines represent the initial rate of polymerization. Right, purified Arp2/3 complex (10 nM) was used as an internal control for the reaction. N, nuclear extract; RA, retinoic acid; CD, cytochalasin D.

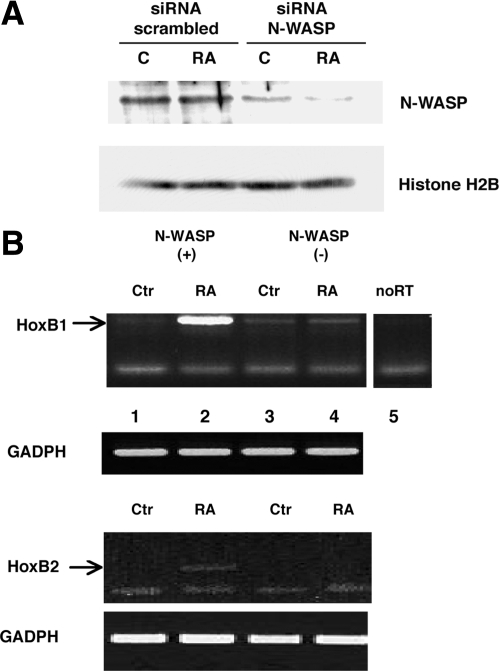

We then decided to down-regulate N-WASP and to study the RA-induction of HoxB1 and HoxB2. Transfection of an h-N-WASP RNAi oligonucleotide into NT2-D1 cells strongly reduced the level of N-WASP in total cell extracts (Figure 2A). The expression level of an internal control, histone H2B, was unaffected. We then compared by RT-PCR the induced level of HoxB1 and HoxB2 mRNAs at high (i.e., normal) and low levels of N-WASP. Figure 2B shows an experiment in which, when N-WASP is down-regulated, the induction of HoxB1 and HoxB2 mRNAs by RA (at 16 h) is abolished, whereas transcription of the constitutive GAPDH gene is not affected. These results confirm that actin polymerization is required at least for the transcription of the 3′ HoxB genes. They further provide a functional connection between RA-induced HoxB transcription and N-WASP. The different levels of HoxB1 versus HoxB2 mRNA in this experiment are expected, because at the time of measurement (24 h) HoxB1 is already fully induced, whereas HoxB2 transcription is at an earlier phase of induction (Simeone et al., 1990).

Figure 2.

Down-regulation of N-WASP prevents HoxB1 and HoxB2 induction by RA. (A) Immunoblotting analysis to assess the down-regulation of N-WASP in NT2-D1 cells. Cells were transfected with an h-N-WASP–interfering oligonucleotide (siRNA) or with a scrambled oligonucleotide (see Materials and Methods). After 24 h, 1 μM RA was added, and 16 h thereafter proteins were isolated and immunoblotted with anti N-WASP and Histone 2b antibodies. (B) N-WASP down-regulation prevents HoxB1 induction. RNA isolated in parallel from the same experiment of A, was subjected to semiquantitative RT-PCR with primers specific for the HoxB1 and GADPH mRNA (see Materials and Methods). Lane 1, control, N-WASP+ cells; lane 2, RA-treated N-WASP+ cells (16 h) in which HoxB1 is induced; lane 3, control N-WASP− cells; lane 4, RA-treated N-WASP− cells; lane 5, control transcription of the sample used in lane 2 performed in the absence of reverse transcriptase. At the bottom, the same RNA samples used for lanes 1–4 were used to measure HoxB2 (with primers specific for HoxB2) and GAPDH RNA (see Materials and Methods). This experiment was carried out in duplicate with identical results.

We obtained identical results when we used N-WASP–specific siRNA oligonucleotides (SC36006), which totally abolished N-WASP expression (not shown).

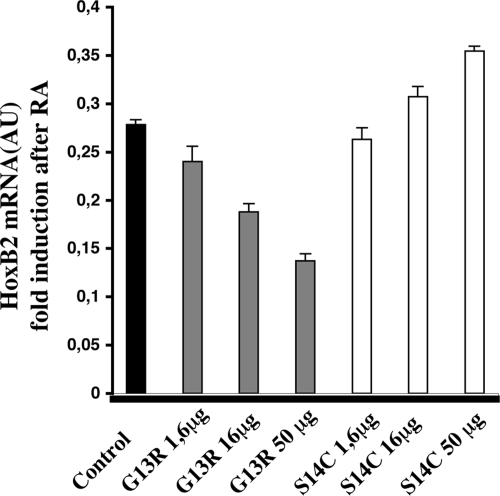

A Nuclear-Targeted Dominant Negative Actin Mutant Blocks HoxB Induction by RA

To further demonstrate a direct role of actin polymerization in gene regulation, we used two actin mutant constructs that contain a nuclear localization signal (NLS) that allows the nuclear localization of the mutant actin forms (Chuang et al., 2006; Dundr et al., 2007). Of these, mRFP-NLS-G13R is deficient in actin polymerization and blocks F-actin polymerization in a dominant-negative manner (Chuang et al., 2006), whereas mRFP-NLS-S14C favors nuclear actin polymerization (Chuang et al., 2006). We transfected these constructs into NT2-D1 cells and confirmed by immunofluorescence the nuclear localization of both RFP-actin mutants (not shown). We measured HoxB2 mRNA levels by real-time PCR after treating cells with RA for 24 h. Figure 3 shows that the G13R mutant decreased the level of RA-induced HoxB2 expression in a dose-dependent manner. Conversely, the S14C mutant, which favors F-actin polymerization, had a slight enhancing effect on HoxB2 expression. This result implicates actin polymerization in the process of transcriptional activation of the HoxB genes. Importantly the use of the nuclear targeted dominant-negative construct that blocks F-actin polymerization excludes the possibility that transcriptional inhibition of the HoxB genes could simply be a secondary effect resulting from an alteration in cytoplasmic actin polymer levels.

Figure 3.

Effect of a dominant-negative actin mutant on the RA-induced HoxB2 transcription. NT2-D1 cells were transfected with 1.6, 16, or 50 μg of DNA encoding either of two variants of actin containing a nuclear localization signal, the G13R mutant that is polymerization-defective (dominant-negative) and the S14C mutant, which is facilitated in polymerization. Cells were treated with RA for 24 h, after which RNA was extracted and HoxB2 mRNA measured by quantitative PCR. The data are the average of at least two independent experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars, SD.

Overall, our data show, using three distinct and independent approaches, that a block of actin polymerization inhibits the RA-dependent transcription of HoxB genes.

The Role of RA Receptors and Prep1 in Actin-dependent HoxB Induction by RA

Because RARs are important in HoxB expression in the neural region (Marshall et al., 1994, 1996; Gould et al., 1998), we tested whether treatment with CytD affected the expression of any of these receptors. As shown in Table 3, CytD did not affect the expression levels of any of the RAR and retinoid X receptor (RXR) transcription factors, either in the absence or in the presence of RA. Therefore, the effect of CytD on HoxB transcription cannot be due to interference with the expression of the RARs. Our results here also confirm that not all inducible genes are sensitive to CytD (see RARα, Table 3).

Table 3.

Lack of effect of 100 nM CytD on the expression of RARs in RA-treated NT2-D1 cells

| Gene | Control | 16 h, RA | 16 h, CytD | 16 h, RA + CytD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RARα | 1.0 | 5.5 | 0.855 | 5.01 |

| RARβ | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| RARγ | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.35 | 1.15 |

| RXRα | 1.0 | 1.09 | 1.35 | 1.15 |

| RXRβ | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.37 | 1.42 |

| RXRγ | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

Cells were treated (or not) with 10 μM RA and/or 100 nM CytD at t = 0, and the level of mRNA was assessed after 16 h.

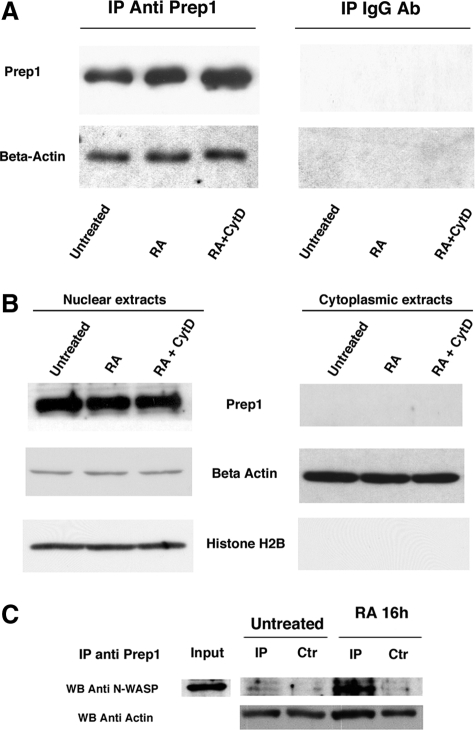

Expression of the 3′ HoxB genes requires Prep1 both in cell culture (including NT2-D1 cells) and in vivo (Ferretti et al., 2000, 2005; Deflorian et al., 2004; Diaz et al., 2007b). We previously showed that β-actin was specifically copurified with Prep1 from the nucleus (but not from the cytoplasm) of NIH-3T3 cells (Diaz et al., 2007a). We immunoprecipitated nuclear extracts from control, RA- (1 μM), or RA + CytD– (100 nM) treated cells with anti-Prep1 antibodies, and the cells were immunoblotted with actin antibodies. Figure 4A confirms this interaction between Prep1 and β-actin and demonstrates that it is constitutive and unaffected by CytD. The interaction of Prep1 and actin is most likely indirect because purified recombinant Prep1 and polymerized actin did not cosediment after high-speed ultracentrifugation (90,000 × g; not shown).

Figure 4.

Prep1 interaction with actin and N-WASP. (A) Nuclear extracts of untreated, 1 μM RA- and RA + CytD-(100 nM) treated NT2-D1 cells were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Prep1 antibody and blotted against a β-actin antibody. Right panel, the results with an irrelevant antibody. (B) RA and CytD do not modify the nuclear localization of Prep1. Nuclear or cytoplasmic extracts of NT2-D1 cells treated as indicated were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. An anti-histone and an anti-β-actin 2B antibody was used to assess equal loading of extracts. (C) RA-dependent interaction of Prep1 with N-WASP. Nuclear extracts from untreated or RA-treated (24 h) cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-Prep1 (IP) or control (Ctr) antibodies and blotted with N-WASP and actin antibodies.

Previous experiments showed that the use of drugs that inhibit actin polymerization control the nuclear translocation of the MAL transcription factor (Vartiainen et al., 2007). To test whether CytD affects Prep1 nucleocytoplasmic distribution, we analyzed nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from control, RA-, or RA + CytD-treated cells by immunoblotting. Our data show that these treatments do not affect Prep1 levels or its nuclear localization (Figure 4B). It is therefore unlikely that inhibition of actin polymerization acts via the sequestration of Prep1.

Finally, because both Prep1 (Diaz et al., 2007b) and N-WASP (see above) are required for HoxB induction in NT2-D1 cells, we tested for the presence of a Prep1–N-WASP interaction in NT2-D1 nuclear extracts by immunoprecipitating with anti-Prep1 and blotting with anti-N-WASP antibodies. N-WASP was immunoprecipitated by anti-Prep1 antibodies only in extracts of RA-treated cells (Figure 4C). Overall, these results suggest that RA induces actin polymerization by recruiting N-WASP into a complex that may already contain actin and Prep1.

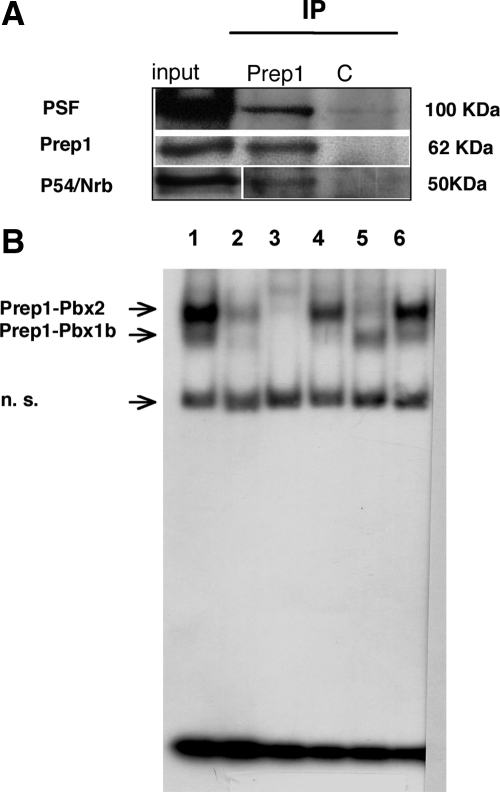

In the nucleus, N-WASP is associated with p54Nrb–PSF (Wu et al., 2006), a protein complex that interacts with both RNAPII and the splicing machinery (Shav-Tal and Zipori, 2002). We therefore tested the association of Prep1 with p54Nrb–PSF. An anti-Prep1 antibody pulled down both p54Nrb and PSF from nuclear extracts of untreated NT2-D1 cells (Figure 5A), in addition to the known Prep1 interactor Pbx1 (not shown). Prep1 was, likewise, immunoprecipitated by PSF antibodies (not shown). We also confirmed (not shown) that PSF antibodies pulled down actin and N-WASP, as previously shown (Wu et al., 2006).

Figure 5.

DNA-binding Prep1 is associated with p54Nrb and PSF. (A) Nuclear extracts of untreated NT2-D1 cells were immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal anti-Prep1 or a control (C) antibody and blotted using polyclonal PSF, Prep1, or p54Nrb antibodies. (B) P54Nrb is present on the DNA-binding Prep1–Pbx complexes. EMSA analysis of HeLa nuclear extracts with the specific Prep1–Pbx-binding oligonucleotide (see Materials and Methods). n.s., nonspecific band. The nuclear extract from HeLa cells (lanes 1 and 6) forms two specifically retarded bands. Prep1 antibodies prevent the formation of both bands (lane 2). The lower band is inhibited by the anti-Pbx1 antibodies (lane 4), whereas the upper band is inhibited by the anti-Pbx2 (lane 5) antibodies. Therefore the two bands are identified as Prep1–Pbx1b (lower band) and Prep1–Pbx2 (upper band) as previously reported (Berthelsen et al., 1998). Formation of both bands is inhibited by anti-p54Nrb antiserum (lane 3).

In preliminary experiments in HeLa cells (in which Prep1 and p54Nrb and PSF are rather abundant), we found that the Prep1–Pbx complex is bound to the p54Nrb component of the p54Nrb–PSF complex (not shown). We also showed that p54Nrb, at least, is part of the Prep1–Pbx DNA-binding complex. We previously showed that, in nuclear extracts of HeLa cells, Prep1 is bound to either of the two isoforms of Pbx, Pbx1b, and Pbx2, forming DNA-binding complexes (Berthelsen et al., 1998). We performed EMSA to test whether p54Nrb is associated with these DNA-binding complexes. As shown in Figure 5B the two bands that formed with the specific labeled oligonucleotide (lane 1) correspond to Prep1–Pbx1a and Prep1–Pbx2 complexes, as expected. Indeed, anti-Prep1 antibodies inhibited the formation of both complexes (lane 2); anti-Pbx1 antibodies inhibited formation of only the lower complex (lane 4), whereas anti-Pbx2 inhibited only the upper complex (lane 5). Importantly, anti-p54Nrb antibodies inhibited the formation of both complexes (lane 3), whereas preimmune IgGs had no effect (lane 6). We conclude that the DNA-binding Prep1–Pbx complex is constitutively associated with p54Nrb.

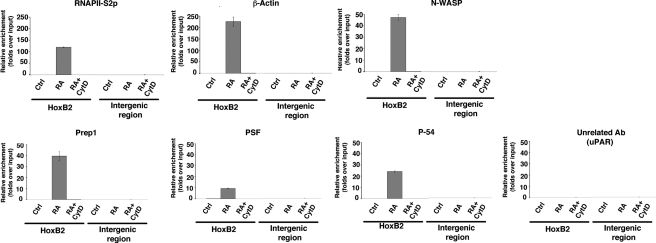

RA Recruits Prep1, RNAPII, the Actin-Polymerization Machinery, and the p54Nrb–PSF Complex onto the Enhancer of the HoxB2 Gene

To confirm the above results we tested whether RA was able to recruit to the regulatory regions of the HoxB genes a complex containing Prep1, actin, and associated components like RNAPII, p54Nrb, PSF, and N-WASP. We immunoprecipitated sonicated, cross-linked chromatin from untreated, RA-, and RA + CytD-treated NT2-D1 cells with antibodies against Prep1, β-actin, N-WASP, p54Nrb, PSF, or RNAPII-S2p and tested by quantitative PCR whether the HoxB2 enhancer was enriched in the immunoprecipitated material. Hyperphosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNAPII is required for its active engagement in transcription. In particular, the initiation form of RNAPII is phosphorylated at serine 5 (RNAPII-S5p), whereas the elongating form of the enzyme is phosphorylated at serine 2 (RNAPII-S2p). Because RNAPII-S5p has recently been shown to be often associated with genes that are on the point of being, but are not yet, transcribed (Stock et al., 2007; Core and Lis, 2008; Ferrai, unpublished data), we used antibodies that recognize RNAPII-S2p as a mark of active transcription. As shown in Figure 6, in the absence of RA, when HoxB2 is not transcribed, none of the antibodies immunoprecipitated the HoxB2 enhancer. However, a strong enrichment of the HoxB2 enhancer was detected after the immunoprecipitation with all the antibodies (Prep1, β-actin, N-WASP, p54Nrb PSF, and RNAPII-S2p) in cells treated with RA for 24 h, a condition in which HoxB2 is transcribed. No enrichment was seen using unrelated control antibodies and the specificity of the immunoprecipitation was further confirmed by the absence of signal in experiments performed using an intergenic region (of the uPA gene; Figure 6). Importantly, cotreatment of RA-induced cells with 100 nM CytD completely prevented the immunoprecipitation of the HoxB2 enhancer sequences by all antibodies, including RNAPII-S2p.

Figure 6.

RA treatment induces the recruitment of Prep1, actin, N-WASP, p54Nrb, PSF, and the elongating form of RNAPII on the enhancer of the HoxB2 gene, but this recruitment is prevented by CytD. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of NT2-D1 cells (untreated, 24-h RA-treated and 24-h RA + CytD-treated). Cross-linked chromatin was immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies and the precipitated DNA amplified by quantitative PCR with oligonucleotides specifically identifying the HoxB2 enhancer or the uPA intergenic region (see Materials and Methods). The antibodies used are indicated on top. Antibodies to RNPII-S2p recognize the elongating form of the RNAPII enzyme. Results and error bars shown are the average and SD of quantitative PCRs performed in triplicate from three independent chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments. Values are reported as fold enrichment relative to input DNA.

This experiment demonstrates that the “active” RNAPII, the specific transcription factor Prep1, the actin polymerization machinery (or, at least, actin and N-WASP) and the two N-WASP– and Prep1-associated factors p54 and PSF are recruited by RA to the enhancer of the HoxB2 gene. Importantly, this recruitment is completely abrogated by CytD. This result not only functionally implicates actin polymerization in the regulation of expression of the HoxB genes, but in particular identifies the mechanism by which actin polymerization affects HoxB induction. Therefore, we conclude that actin polymerization is functionally implicated in the transcriptional regulation of HoxB genes, showing for the first time that actin polymerization is required to recruit the transcription complex onto the regulatory region of HoxB2.

DISCUSSION

The role of actin and its participation in transcription by all three forms of RNAP is well documented in vivo and in vitro (Visa, 2005; Percipalle and Visa, 2006). However, despite the importance of nuclear actin, the exact role of actin polymerization and its impact in transcription is still unclear. In this article, we have shown that the RA induction of the HoxB genes is inhibited by rather low doses of CytD and LatA, by the down-regulation of N-WASP, and by the use of a dominant-negative actin mutant. On the other hand, F-actin stabilizers jasplakinolide and phalloidin as well as a dominant-positive actin mutant slightly enhance HoxB transcription. Overall our data demonstrate that the induction of the HoxB genes requires actin polymerization.

Importantly because CytD and LatA inhibit HoxB induction only when added before the start of transcription (Table 1), actin polymerization appears to be required for the initiation of transcription. Moreover, other RA-inducible genes, such as HoxA1, -A2, and Meis1 or the constitutively expressed gene Eps8 (Tables 1 and 2), are not affected by CytD and LatA. Likewise, although the down-regulation of N-WASP prevents HoxB1 and HoxB2 induction, it has no effect on the levels of expression of the housekeeping gene GAPDH (Figure 1). Even the RA-inducible RARα gene was not sensitive to CytD (Table 3). Thus, it appears that specific genes are differentially sensitive to the inhibition of actin polymerization.

Previous data have shown that CytD affects general transcription (McDonald et al., 2006). However, these data were obtained at a concentrations (1 μM) of CytD 10-fold higher than those used in the present article, in which we nevertheless achieved a strong, but incomplete inhibition of actin polymerization (McDonald et al., 2006). The intriguing evidence that different subsets of genes could be differentially sensitive to the inhibition of actin polymerization is new. On the basis of the present and of the literature data, we conclude that actin polymerization is generally required for transcription; however, this requirement may vary from gene to gene. Our data give no indication that different forms of polymeric actin (possibly differentially sensitive to CytD) are involved, although this cannot be excluded.

The possibility that CytD or N-WASP down-regulation might affect HoxB transcription by regulating the subcellular localization of Prep1 was considered because CytD inhibits the nuclear translocation of MAL (Vartiainen et al., 2007). However, Prep1 is present in the nucleus of NT2-D1 cells both before and after RA treatment, and its localization is unaffected by CytD (Figure 4B). Furthermore, because a dominant-negative actin mutant with a NLS also inhibits HoxB induction, the inhibitory effect of CytD is likely due to its inhibitory effect on nuclear actin polymerization.

We also report that RA treatment slightly affects actin polymerization in nuclear extracts. The conditions we used favor the formation of a tripartite complex between monomeric actin, the WCA domain of N-WASP and Arp2/3, leading to a slight but detectable enhancement of actin polymerization (Figure 1). Although the molecular mechanism through which RA controls this process is unclear, it is conceivable that the assembly of sequence-specific transcription factors and of an actin-polymerization–competent complex is coordinated on at least some RA-dependent promoters, providing spatially confined actin dynamics that aid transcription initiation.

We also found that Prep1 (which is normally present in a DNA-binding complex with Pbx1) is associated with p54Nrb and PSF. These two accessory splicing factors also bind RNAPII and other transcription factors (Shav-Tal and Zipori, 2002) as well as N-WASP (Wu et al., 2006), whose down-regulation prevents HoxB induction by RA (Figure 2). Although in a different cell model (HeLa cells), we show that Prep1 and Pbx1 bind p54Nrb and that the resulting complex still binds DNA (Figure 5B), which indicates that these proteins can be recruited to the same DNA target sequence. Indeed these two proteins are recruited in NT2-D1 cells after induction with RA, together with actin, Prep1, N-WASP, and RNAPII onto the enhancer of the HoxB2 gene. Importantly, none of these proteins is associated with DNA in the absence of RA induction or when the RA induction of gene expression is prevented by CytD treatment (Figure 6). These data demonstrate that the recruitment of these proteins in vivo to the enhancer of a HoxB gene requires both actin polymerization and RA.

RA therefore induces the recruitment of both sequence-specific DNA-binding elements (Prep1 at the very least, but more likely the Prep1–Pbx1 dimer or the Prep1–Pbx1-HoxB1 trimer; Ferretti et al., 2000, 2005), actin, and its polymerizing enzyme(s) N-WASP and RNAPII.

In the chromatin immunoprecipitation experiment of Figure 6, the presence of the active form of RNAPII-S2p on the HoxB2 enhancer demonstrates that the RA-recruited proteins are actively involved in transcription. These data are therefore in complete agreement with the inhibition of HoxB transcription by all conditions that block actin polymerization. The same complex is also likely present on the enhancer of HoxB1 (because Prep1 also regulates this gene; Ferretti et al., 2000, 2005). The nature of the β-actin–Prep1 interaction is still unknown. Although the two proteins can easily be coimmunoprecipitated (Figure 4A), the interaction is most likely indirect. The protein connecting Prep1 to actin is probably N-WASP, a member of the WASP family of proteins that regulates actin filaments in the cytoplasm and whose nuclear localization can be regulated by its activation state and by phosphorylation (Wu et al., 2004). In the nucleus of 293T cells, N-WASP is associated with the p54Nrb–PSF complex (Wu et al., 2006). Because the p54Nrb–PSF complex binds both N-WASP (Wu et al., 2006) and Prep1–Pbx1 (Figure 5A), it might also be the link between the actin polymerization machinery and Prep1–Pbx1. Preliminary experiments from our laboratory have demonstrated that p54Nrb binds the Pbx1 moiety of the Prep1–Pbx1 complex (Palazzolo and Blasi, unpublished data).

The interaction of actin with Prep1 and its presence on the enhancer of HoxB2 is functionally relevant because HoxB2 expression in vivo during embryogenesis depends on the activity of the Prep1–Pbx1 complex (Waskiewicz et al., 2002; Deflorian et al., 2004; Di Rosa et al., 2007). Here we show that actin polymerization is involved in the induction of the HoxB genes by regulating the recruitment of the large transcriptional complex on the regulatory sequence. Our results not only reinforce previous data showing that actin plays a key role in transcription, but highlight the participation of actin polymerization in orchestrating transcription and in fine tuning the transcriptome, acting at different levels in different subclasses of genes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors dedicate this article to the memory of Ludovico Faini. We thank Ana Pombo and Tom Misteli for critically reading the manuscript. Flavia Troglio and Maud Hertzog helped with the N-WASP RNAi design and the in vitro actin polymerization. We thank Laura Tizzoni from the IFOM PCR facility for QT-PCR. This work was supported by Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) and Telethon Onlus to F.B. and from AIRC and Ministero della Sanità to M.P.C. V.M.D. was a recipient of an EU Marie Curie fellowship. The authors are indebted to Dr. A. Krainer and J. Patton for their generous gifts of cDNA and antibodies directed against p54 and PSF and to Andrew Belmont (University of Illinois, Urbana, IL) for providing the mRFP-NLS-G13R and mRFP-NLS-S14C actin mutants.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E09-02-0114) on May 28, 2009.

REFERENCES

- Berthelsen J., Zappavigna V., Ferretti E., Mavilio F., Blasi F. The novel homeoprotein Prep1 modulates Pbx-Hox protein cooperativity. EMBO J. 1998;17:1434–1445. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger B. T., Gilbert D. M., Amberg D. C. Actin up in the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;5:410–415. doi: 10.1038/nrm1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang C. H., Carpenter A. E., Fuchsova B., Johnson T., de Lanerolle P., Belmont A. S. Long-range directional movement of an interphase chromosome site. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:825–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Core L. J., Lis J. T. Transcription regulation through promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II. Science. 2008;319:1791–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.1150843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deflorian G., Tiso N., Ferretti E., Meyer D., Blasi F., Bortolussi M., Argenton F. Prep1.1 has essential genetic functions in hindbrain development and cranial neural crest cell differentiation. Development. 2004;131:613–627. doi: 10.1242/dev.00948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Rosa P., Villaescusa J. C., Longobardi E., Iotti G., Ferretti E., Diaz V. M., Miccio A., Ferrari G., Blasi F. The homeodomain transcription factor Prep1 (pKnox1) is required for hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell activity. Dev. Biol. 2007;311:324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz V. M., Bachi A., Blasi F. Purification of the Prep1 interactome identifies novel pathways regulated by Prep1. Proteomics. 2007a;7:2617–2623. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz V. M., Mori S., Longobardi E., Menendez G., Ferrai C., Keough R. A., Bachi A., Blasi F. p160 Myb-binding protein interacts with Prep1 and inhibits its transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007b;27:7981–7990. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01290-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam J. D., Lebovitz R. M., Roeder R. G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disanza A., et al. Regulation of cell shape by Cdc42 is mediated by the synergic actin-bundling activity of the Eps8-IRSp53 complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:1337–1347. doi: 10.1038/ncb1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundr M., Ospina J. K., Sung M. H., John S., Upender M., Ried T., Hager G. L., Matera A. G. Actin-dependent intranuclear repositioning of an active gene locus in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:1095–1103. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupe V., Ghyselinck N. B., Wendling O., Chambon P., Mark M. Key roles of retinoic acid receptors alpha and beta in the patterning of the caudal hindbrain, pharyngeal arches and otocyst in the mouse. Development. 1999;126:5051–5059. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.5051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egly J. M., Miyamoto N. G., Moncollin V., Chambon P. Is actin a transcription initiation factor for RNA polymerase B? EMBO J. 1984;3:2363–2371. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrai C., Munari D., Luraghi P., Pecciarini L., Cangi M. G., Doglioni C., Blasi F., Crippa M. P. A transcription-dependent micrococcal nuclease-resistant fragment of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator promoter interacts with the enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:12537–12546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700867200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti E., Cambronero F., Tumpel S., Longobardi E., Wiedemann L. M., Blasi F., Krumlauf R. Hoxb1 enhancer and control of rhombomere 4 expression: complex interplay between PREP1-PBX1-HOXB1 binding sites. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:8541–8552. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.19.8541-8552.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti E., Marshall H., Popperl H., Maconochie M., Krumlauf R., Blasi F. Segmental expression of Hoxb2 in r4 requires two separate sites that integrate cooperative interactions between Prep1, Pbx and Hox proteins. Development. 2000;127:155–166. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti E., et al. Hypomorphic mutation of the TALE gene Prep1 (pKnox1) causes a major reduction of Pbx and Meis proteins and a pleiotropic embryonic phenotype. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:5650–5662. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00313-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomproix N., Percipalle P. An actin-myosin complex on actively transcribing genes. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;294:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould A., Itasaki N., Krumlauf R. Initiation of rhombomeric Hoxb4 expression requires induction by somites and a retinoid pathway. Neuron. 1998;21:39–51. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grummt I. Actin and myosin as transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2006;16:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P., Wu S., Hernandez N. A role for beta-actin in RNA polymerase III transcription. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3010–3015. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D., Chen S. W., Gudas L. J. Analysis of two distinct retinoic acid response elements in the homeobox gene Hoxb1 in transgenic mice. Dev. Dyn. 2002;223:353–370. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs Y., Schnabel C. A., Cleary M. L. Trimeric association of Hox and TALE homeodomain proteins mediates Hoxb2 hindbrain enhancer activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:5134–5142. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jockusch B. M., Schoenenberger C. A., Stetefeld J., Aebi U. Tracking down the different forms of nuclear actin. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumlauf R. Hox genes in vertebrate development. Cell. 1994;78:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukalev A., Nord Y., Palmberg C., Bergman T., Percipalle P. Actin and hnRNP U cooperate for productive transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:238–244. doi: 10.1038/nsmb904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maconochie M. K., Nonchev S., Studer M., Chan S. K., Popperl H., Sham M. H., Mann R. S., Krumlauf R. Cross-regulation in the mouse HoxB complex: the expression of Hoxb2 in rhombomere 4 is regulated by Hoxb1. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1885–1895. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall H., Morrison A., Studer M., Popperl H., Krumlauf R. Retinoids and Hox genes. FASEB J. 1996;10:969–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall H., Studer M., Popperl H., Aparicio S., Kuroiwa A., Brenner S., Krumlauf R. A conserved retinoic acid response element required for early expression of the homeobox gene Hoxb-1. Nature. 1994;370:567–571. doi: 10.1038/370567a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald D., Carrero G., Andrin C., de Vries G., Hendzel M. J. Nucleoplasmic beta-actin exists in a dynamic equilibrium between low-mobility polymeric species and rapidly diffusing populations. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:541–552. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrdlik A., Kukalev A., Percipalle P. The function of actin in gene transcription. Histol. Histopathol. 2007;22:1051–1055. doi: 10.14670/HH-22.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olave I. A., Reck-Peterson S. L., Crabtree G. R. Nuclear actin and actin-related proteins in chromatin remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002;71:755–781. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaloni D., Boujemaa R., Didry D., Gounon P., Carlier M. F. The Arp2/3 complex branches filament barbed ends: functional antagonism with capping proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:385–391. doi: 10.1038/35017011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaloni D., Le Clainche C., Carlier M. F. Mechanism of actin-based motility. Science. 2001;292:1502–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.1059975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson T., Aebi U. Actin in the nucleus: what form and what for? J. Struct. Biol. 2002;140:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penkov D., Di Rosa P., Fernandez Diaz L., Basso V., Ferretti E., Grassi F., Mondino A., Blasi F. Involvement of Prep1 in the alphabeta T-cell receptor T-lymphocytic potential of hematopoietic precursors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:10768–10781. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10768-10781.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percipalle P., Visa N. Molecular functions of nuclear actin in transcription. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:967–971. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philimonenko V. V., Zhao J., Iben S., Dingova H., Kysela K., Kahle M., Zentgraf H., Hofmann W. A., de Lanerolle P., Hozak P., Grummt I. Nuclear actin and myosin I are required for RNA polymerase I transcription. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:1165–1172. doi: 10.1038/ncb1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi R., Ma L., Miki H., Lopez M., Kirchhausen T., Takenawa T., Kirschner M. W. The interaction between N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex links Cdc42-dependent signals to actin assembly. Cell. 1999;97:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo H. D., Marty T., Casares F., Affolter M., Mann R. S. Regulation of Hox target genes by a DNA bound Homothorax/Hox/Extradenticle complex. Development. 1999;126:5137–5148. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.5137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer U., Hinssen H., Franke W. W., Jockusch B. M. Microinjection of actin-binding proteins and actin antibodies demonstrates involvement of nuclear actin in transcription of lampbrush chromosomes. Cell. 1984;39:111–122. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selleri L., Depew M. J., Jacobs Y., Chanda S. K., Tsang K. Y., Cheah K. S., Rubenstein J. L., O'Gorman S., Cleary M. L. Requirement for Pbx1 in skeletal patterning and programming chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Development. 2001;128:3543–3557. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.18.3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shav-Tal Y., Zipori D. PSF and p54(nrb)/NonO—multi-functional nuclear proteins. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone A., Acampora D., Arcioni L., Andrews P. W., Boncinelli E., Mavilio F. Sequential activation of HOX2 homeobox genes by retinoic acid in human embryonal carcinoma cells. Nature. 1990;346:763–766. doi: 10.1038/346763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock J. K., Giadrossi S., Casanova M., Brookes E., Vidal M., Koseki H., Brockdorff N., Fisher A. G., Pombo A. Ring1-mediated ubiquitination of H2A restrains poised RNA polymerase II at bivalent genes in mouse ES cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:1428–1435. doi: 10.1038/ncb1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartiainen M. K., Guettler S., Larijani B., Treisman R. Nuclear actin regulates dynamic subcellular localization and activity of the SRF cofactor MAL. Science. 2007;316:1749–1752. doi: 10.1126/science.1141084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visa N. Actin in transcription. Actin is required for transcription by all three RNA polymerases in the eukaryotic cell nucleus. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:218–219. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waskiewicz A. J., Rikhof H. A., Moens C. B. Eliminating zebrafish pbx proteins reveals a hindbrain ground state. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:723–733. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00319-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Suetsugu S., Cooper L. A., Takenawa T., Guan J. L. Focal adhesion kinase regulation of N-WASP subcellular localization and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:9565–9576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310739200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Yoo Y., Okuhama N. N., Tucker P. W., Liu G., Guan J. L. Regulation of RNA-polymerase-II-dependent transcription by N-WASP and its nuclear-binding partners. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:756–763. doi: 10.1038/ncb1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., Zhao J., Hoffmann-Rohrer U., Grummt I. Nuclear myosin I acts in concert with polymeric actin to drive RNA polymerase I transcription. Genes Dev. 2008;22:322–330. doi: 10.1101/gad.455908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo Y., Wu X., Guan J. L. A novel role of the actin-nucleating Arp2/3 complex in the regulation of RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:7616–7623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.