Abstract

The exact residues within severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) S1 protein and its receptor, human ACE2, involved in their interaction still remain largely undetermined. Identification of exact amino acid residues that are crucial for the interaction of S1 with ACE2 could provide working hypotheses for experimental studies and might be helpful for the development of antiviral inhibitor. In this paper, a molecular docking model of SARS-CoV S1 protein in complex with human ACE2 was constructed. The interacting residue pairs within this complex model and their contact types were also identified. Our model, supported by significant biochemical evidence, suggested receptor-binding residues were concentrated in two segments of S1 protein. In contrast, the interfacial residues in ACE2, though close to each other in tertiary structure, were found to be widely scattered in the primary sequence. In particular, the S1 residue ARG453 and ACE2 residue LYS341 might be the key residues in the complex formation.

Keywords: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Spike protein, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, Receptor binding, Protein docking

1. Introduction

As a structural glycoprotein on the virion surface, the spike protein of coronavirus is responsible for binding to host cellular receptors and the following fusion between the viral envelope and the cellular membrane (Hofmann and Pohlmann, 2004). The identification of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a functional receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) (Li et al., 2003) has provided insights into the host range, cell tropism and pathogenesis of this newly identified etiological agent. Binding analyses (Babcock et al., 2004, Wong et al., 2004) localized a 193 amino-acid (residues 318–510) receptor-binding domain (RBD) in the S1 domain of SARS-CoV spike glycoprotein. This fragment was shown to bind ACE2 more potently than the full-length S1 domain, and an initial search for S-protein residues critical to receptor-binding also pinpointed GLU452 and ASP454 within this fragment. However, the exact residues within S1 and ACE2 involved in their interaction still remain largely undetermined (Hofmann and Pohlmann, 2004). Since previous structural bioinformatics technology has showed its great power in the study of SARS-CoV (Cai et al., 2003, Yu et al., 2003, Liu et al., 2004a, Liu et al., 2004b, Zhang and Yap, 2004, Zhang et al., 2004), we expect a molecular docking model (PDB code: 1XJP) of S1/ACE2 complex presented here will be helpful to uncover amino acid residues potentially crucial for the association between S1 and ACE2.

2. Materials and methods

The theoretical model of the SARS-CoV S1 domain (PDB code: 1Q4Z) (Spiga et al., 2003) and the native crystal structure of the human ACE2 extracellular domain (PDB code: 1R42) (Towler et al., 2004) were downloaded from the protein data bank (PDB) (Berman et al., 2000) and used as inputs to the fully automatic ZDOCK (Chen and Weng, 2003) server (http://zdock.bu.edu/) for protein docking computation. Relying on a composite scoring function combining pairwise shape complementarity with desolvation and electrostatics (Chen and Weng, 2003), ZDOCK uses a fast Fourier transform based algorithm (Chen and Weng., 2002) to perform a global search in the translational and rotational space without the need for assumption about binding sites. As shown in previous critical assessment of prediction of interaction (CAPRI) challenge, ZDOCK is among the best for protein docking algorithms (Chen et al., 2003a, Chen et al., 2003b). But due to the difficulty of protein docking task, ZDOCK server, like other approaches, always generates multiple predictions ranked in descending order on the basis of scoring function for one target, and consequently the identification and incorporation of crucial biological knowledge must play a significant role in the following manual inspection to choose the most likely complex model (Chen et al., 2003a, Chen et al., 2003b). In this case, a previous study derived from a homologous model of ACE2 (Prabakaran et al., 2004) has indicated that the distal ridge of this molecule was likely to participate in binding because there was no room for the S1 protein to associate with its receptor at the cellular membrane proximal face of the ACE2 ectodomain. Moreover, a recent research (Moore et al., 2004), suggesting that the S protein-binding site of ACE2 is topologically separated from its catalytic site that is surrounded by the two distal ridges, further strengthened this point of view. Furthermore, the previously identified RBD, especially the two key residues within this fragment, must be on the interface of selected complex model. In conclusion, our criteria for model selection is to choose the highest ranked prediction in agreement with the biological information mentioned above. Based on the criteria, the fourth model, out of 1000 predictions generated, was proposed as the best model (Fig. 1 ). Subsequently, interface forming residue graphical contacts (IFRgc) (Mancini et al., 2004), which is a web-based tool integrated in the STING Millennium Suite (Higa et al., 2004) (http://asparagin.cenargen.embrapa.br/SMS/), was used to identify and analyze amino acid contacts across protein interfaces within the proposed complex model. The resulting list of interacting residue pairs and their contact types are shown in Table 1 .

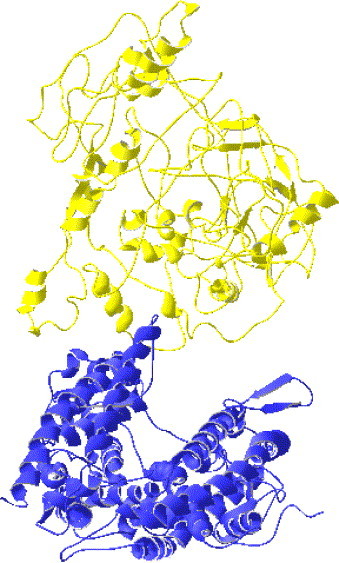

Fig. 1.

Ribbon diagram of the SARS-CoV S1 (yellow)/ACE2 (blue) complex model (PDB code: 1XJP). The theoretical model of S1 domain (PDB code: 1Q4Z) and the native crystal structure of the human ACE2 extracellular domain (PDB code: 1R42) were downloaded from the protein data bank (PDB). This model was generated by the fully automatic ZDOCK protein–protein docking server and manually selected on the basis of structural biology knowledge.

Table 1.

The interacting residue pairs in the S1/ACE2 complex model

| S1 residue | ACE2 residue | Contact type |

|---|---|---|

| VAL307 | VAL298 | Hydrophobic interaction |

| VAL308 | VAL298 | |

| VAL308 | VAL364 | |

| ASP312 | THR334 | |

| PRO450 | LYS341 | |

| ARG453 | LYS341 | |

| ARG449 | GLU57 | Electrostatic interaction (attractive) |

| ARG453 | GLU56 | |

| ASP454 | LYS341 | |

| ASP312 | ASP335 | Electrostatic interaction (repulsive) |

| ARG453 | LYS341 | Hydrogen bond |

| ASP312 | THR334 | |

3. Results and discussion

In our selected complex model, a positively charged cavity at the distal end of S1 protein envelopes one highly negatively charged ridge on the top of ACE2, i.e., it is consistent with earlier speculation stated above. And contacting residues are concentrated in two segments of S1 ternary structure. One segment, including four residues (ARG449, PRO450, ARG453, and ASP454) nested in the previously identified RBD, contained all of the three attractive charged residues determined above. In particular, the residue ARG453 interacted in several ways—electrostatic complementarity, hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions—with the residues LYS341 and GLU56 of ACE2. This suggests that it might be the key residue in the complex formation. Moreover, the negative charge of ASP454 complemented the positive charge of ACE2 residue LYS341, in agreement with the observation that the substitution of ASP454 with alanine completely inhibited ACE2 binding (Wong et al., 2004). Similarly, another important residue (GLU452) (Wong et al., 2004) was adjacent to the interface of this complex, hinting at a possible effect on the receptor binding. All of this evidence suggests that this segment is probably the primary determinant for formation of the complex and hence could be an attractive target for antiviral inhibitors. In contrast, the other segment comprising of the remaining three residues, might only provide a secondary contribution to the complex formation because it is not nested in the RBD. Notably, the existence of electrostatic repulsion at the residue ASP312, even though it might be partially counteracted by the hydrogen bond at the same site, could serve as a likely explanation for the low receptor-binding affinity of the whole S1 protein relative to that of the RBD (Wong et al., 2004).

Unlike the S1 protein, the interfacial residues in ACE2 ectodomain, though close to each other in tertiary structure, were found to be widely scattered in the primary sequence. One instance was the hydrophobic patch formed by the residues VAL298, THR334, LYS341 and VAL364. The other example was that two neighboring acidic residues (GLU56 and GLU57) and a distant basic residue (LYS341) together formed attractive electrostatic interactions with three adjacent residues (ARG449, ARG453 and ASP454) in the S1 tertiary structure. The residue LYS341, similarly to its counterpart the S1 residue ARG453, made multiple contacts with residues of the S1 protein, playing a central role in the associations between ACE2 and S1. Also, recent research (Li et al., 2004) showed that murine ACE2 bound the S1 domain of SARS-CoV with lower affinity than the human receptor and allowed less-efficient spike protein-mediated cellular entry. Consequently, the comparison between human and murine ACE2 sequences could provide valuable information on the mapping of the S protein-binding region onto ACE2. In fact, the pairwise alignment of human ACE2 (GenBank accession number: AAT45083) and its murine homolog (GenBank accession number: AAH26801) revealed two point mutations occurring at the interfacial sites. One was the substitution from human VAL298 to murine methionine while another was the residue ASP335 in human sequence substituted with murine glutamate. Both substitutions lead to an increase in side chain volume that may cause steric hindrance or clash with contacting residues. Finally, it is reasonable to expect that the substitution of ASP335 with basic amino acids, such as lysine, will result in greatly increased S1 protein-binding affinity. In other words, a fragment containing THR334, LYS341 and mutated residue 335 might have the potential to effectively block the receptor binding and cellular entry of SARS-CoV.

In summary, the results presented here reveal amino acid residues potentially crucial for the interaction of S1 with ACE2, and offer an opportunity for the application of site-directed mutagenesis technology to test our hypothesis and the development of effective antiviral therapies. In fact, our hypothesis has been strengthened by a recently published docking study (Huentelman et al., 2004) in which a novel ACE2 inhibitor that potently blocked the SARS-CoV spike protein-mediated cell fusion, was successfully identified and experimentally confirmed. Moreover, the roles of two S1 segments, implied by our model, can be strongly supported by some preliminary results [Hsiao et al., unpublished data, abstract available at http://www.egms.de/en/meetings/sars2004/04sars058.shtml] that identified two separate ACE2-binding domains on the S1 protein. The low affinity binding domain was mapped within the N-terminal 333 residues while the high affinity binding domain was located between the residue 334 and 666. Furthermore, rabbit antisera raised against peptide fragment, which corresponded to S1 residues 433–467 (containing our predicted primary determinant), could completely block S protein binding to VERO E6 cells that use ACE2 as the receptor for SARS-CoV. Clearly, all of this evidence indicates that our complex model is very likely to shed light on the development of oligopeptide competitive inhibitors.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Key Projects for Basic Research (973) (2002CB512801, 2003CB715904). Editors’ Note added in proof

The Editors and the Authors decided to publish this paper as soon as possible because of a very high potential medical importance of the findings. We are aware of the fact that the evidence based on molecular docking alone may not be strong enough to fully justify the conclusions reached in this commentary paper.

References

- Babcock G.J., Esshaki D.J., Thomas W.D., Jr., Ambrosino D.M. Amino acids 270 to 510 of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein are required for interaction with receptor. J. Virol. 2004;78:4552–4560. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4552-4560.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T.N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I.N., Bourne P.E. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q.C., Jiang Q.W., Zhao G.M., Guo Q., Cao G.W., Chen T. Putative caveolin-binding sites in SARS-CoV proteins. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2003;24:1051–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Li L., Weng Z. ZDOCK: an initial-stage protein-docking algorithm. Proteins. 2003;52:80–87. doi: 10.1002/prot.10389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Tong W., Mintseris J., Li L., Weng Z. ZDOCK predictions for the CAPRI challenge. Proteins. 2003;52:68–73. doi: 10.1002/prot.10388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Weng Z. Docking unbound proteins using shape complementarity. desolvation, and electrostatics. Proteins. 2002;47:281–294. doi: 10.1002/prot.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Weng Z. A novel shape complementarity scoring function for protein–protein docking. Proteins. 2003;51:397–408. doi: 10.1002/prot.10334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higa R.H., Togawa R.C., Montagner A.J., Palandrani J.C., Okimoto I.K., Kuser P.R., Yamagishi M.E., Mancini A.L., Neshich G. STING Millennium Suite: integrated software for extensive analyses of 3D structures of proteins and their complexes. BMC Bioinform. 2004;5:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann H., Pohlmann S. Cellular entry of the SARS coronavirus. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huentelman M.J., Zubcevic J., Hernandez Prada J.A., Xiao X., Dimitrov D.S., Raizada M.K., Ostrov D.A. Structure-based discovery of a novel angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 inhibitor. Hypertension. 2004;44:903–906. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000146120.29648.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Greenough T.C., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J.L., Farzan M., Choe H. Efficient replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in mouse cells is limited by murine angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Virol. 2004;78:11429–11433. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11429-11433.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S.K., Berne M.A., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J.L., Luzuriaga K., Greenough T.C., Choe H., Farzan M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.L., Lin J.C., Ho Y., Hsieh W.C., Chen C.W., Su Y.C. Homology models and molecular dynamics simulations of main proteinase from coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2004;51:889–900. doi: 10.1002/jccs.200400134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.L., Lin J.C., Ho Y., Hsieh W.C., Chen C.W., Su Y.C. Molecular dynamics simulations of various coronavirus main proteinases. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2004;22:65–78. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2004.10506982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini A.L., Higa R.H., Oliveira A., Dominiquini F., Kuser P.R., Yamagishi M.E., Togawa R.C., Neshich G. STING contacts: a web-based application for identification and analysis of amino acid contacts within protein structure and across protein interfaces. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2145–2147. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M.J., Dorfman T., Li W., Wong S.K., Li Y., Kuhn J.H., Coderre J., Vasilieva N., Han Z., Greenough T.C., Farzan M., Choe H. Retroviruses pseudotyped with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein efficiently infect cells expressing angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Virol. 2004;78:10628–10635. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10628-10635.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabakaran P., Xiao X., Dimitrov D.S. A model of the ACE2 structure and function as a SARS-CoV receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;314:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiga O., Bernini A., Ciutti A., Chiellini S., Menciassi N., Finetti F., Causarono V., Anselmi F., Prischi F., Niccolai N. Molecular modelling of S1 and S2 subunits of SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;310:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towler P., Staker B., Prasad S.G., Menon S., Tang J., Parsons T., Ryan D., Fisher M., Williams D., Dales N.A., Patane M.A., Pantoliano M.W. ACE2 X-ray structures reveal a large hinge-bending motion important for inhibitor binding and catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:17996–18007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311191200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S.K., Li W., Moore M.J., Choe H., Farzan M. A 193-amino acid fragment of the SARS coronavirus S prote in efficiently binds angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:3197–3201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.J., Luo C., Lin J.C., Hao P., He Y.Y., Guo Z.M., Qin L., Su J., Liu B.S., Huang Y., Nan P., Li C.S., Xiong B., Luo X.M., Zhao G.P., Pei G., Chen K.X., Shen X., Shen J.H., Zou J.P., He W.Z., Shi T.L., Zhong Y., Jiang H.L., Li Y.X. Putative hAPN receptor binding sites in SARS_CoV spike protein. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2003;24:481–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.W., Yap Y.L. The 3D structure analysis of SARS-CoV S1 protein reveals a link to influenza virus neuraminidase and implications for drug and antibody discovery. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem. 2004;681:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.theochem.2004.04.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zheng N., Hao P., Zhong Y. Reconstruction of the most recent common ancestor sequences of SARS-Cov S gene and detection of adaptive evolution in the spike protein. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2004;49:1311–1313. doi: 10.1360/04wc0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]