Abstract

Benzimidazole nucleosides have been shown to be potent inhibitors of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) replication in vitro. As part of the exploration of structure-activity relationships within this series, we synthesized the 2-isopropylamino derivative (3322W93) of 1H-β-d-ribofuranoside-2-bromo-5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole (BDCRB) and the biologically unnatural l-sugars corresponding to both compounds. One of the l derivatives, 1H-β-l-ribofuranoside-2-isopropylamino-5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole (1263W94), showed significant antiviral potency in vitro against both laboratory HCMV strains and clinical HCMV isolates, including those resistant to ganciclovir (GCV), foscarnet, and BDCRB. 1263W94 inhibited viral replication in a dose-dependent manner, with a mean 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.12 ± 0.01 μM compared to a mean IC50 for GCV of 0.53 ± 0.04 μM, as measured by a multicycle DNA hybridization assay. In a single replication cycle, 1263W94 treatment reduced viral DNA synthesis, as well as overall virus yield. HCMV mutants resistant to 1263W94 were isolated, establishing that the target of 1263W94 was a viral gene product. The resistance mutation was mapped to the UL97 open reading frame. The pUL97 protein kinase was strongly inhibited by 1263W94, with 50% inhibition occurring at 3 nM. Although HCMV DNA synthesis was inhibited by 1263W94, the inhibition was not mediated by the inhibition of viral DNA polymerase. The parent benzimidazole d-riboside BDCRB inhibits viral DNA maturation and processing, whereas 1263W94 does not. The mechanism of the antiviral effect of l-riboside 1263W94 is thus distinct from those of GCV and of BDCRB. In summary, 1263W94 inhibits viral replication by a novel mechanism that is not yet completely understood.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a herpesvirus that causes a benign infection in an estimated 40 to 100% of populations in the United States (reviewed by Sia and Patel [23]). In most cases, HCMV infection is not associated with disease; however, in patients with an immature or compromised immune system, HCMV infection can be a serious or even life-threatening disease. Four drugs—ganciclovir (GCV), its prodrug valganciclovir, cidofovir, and foscarnet—are currently used for the treatment of systemic HCMV infection; however, there are a number of disadvantages associated with each of these therapies. Cidofovir and foscarnet are available only as intravenous formulations, whereas GCV is given intravenously for initial treatment of systemic disease. With all anti-HCMV drugs currently available, there can be serious side effects associated with prolonged treatment. In addition, the drugs have similar mechanisms of action, all ultimately targeting the HCMV polymerase; therefore, selection of cross-resistant HCMV mutants can occur. Thus, there is a need for other therapeutic agents that are safe, potent, and orally bioavailable, with a novel mechanism of action.

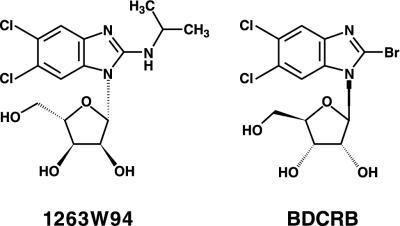

As part of an ongoing program to develop novel anti-HCMV compounds that could potentially yield new therapeutic agents for treatment of HCMV, a series of benzimidazole compounds have been evaluated and shown to be potent inhibitors of HCMV replication in vitro (8, 26, 30). One compound, 1H-β-d-ribofuranoside-2-bromo-5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole(BDCRB) (Fig. 1), was shown to be highly selective against HCMV in vitro and relatively nontoxic both to laboratory cell lines and to primary human bone marrow progenitor cells (21, 26). In addition, BDCRB was shown to inhibit HCMV replication by a novel mechanism: unlike GCV, BDCRB did not inhibit HCMV DNA synthesis but instead blocked the maturational cleavage of high-molecular-weight DNA, a step mediated by the products of the UL89 and UL56 genes (17, 27). However, pharmacokinetic studies in rats and monkeys revealed that the glycosidic bond of BDCRB was rapidly cleaved in a first-pass metabolic process, liberating the inactive and significantly more toxic aglycone (2-bromo-5,6-dichloro benzimidazole) (8).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of 1263W94 and BDCRB.

In an attempt to circumvent the metabolic instability of BDCRB, we designed additional compounds that were analogues of BDCRB. We replaced the 2′-halogen with an isopropylamine moiety to create 1H-β-d-ribofuranoside-2-isopropylamino-5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole (3322W93), and we synthesized the biologically unnatural l-sugars corresponding to both BDCRB and 3322W93. The antiviral properties of these compounds were assessed by standard assays. Compared to the parent compound, BDCRB, one of these derivatives, 1H-β-l-ribofuranoside-2-isopropylamino-5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole (1263W94; Fig. 1), showed significantly increased potency in vitro, similarly low cytotoxicity, and a unique mechanism of action.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents.

BDCRB and its l-ribofuranosyl analog (3858W92) were synthesized according to previously published procedures (26). Compound 1263W94 (Fig. 1) and its d-ribofuranosyl and carbocyclic analogs (3322W93 and 2916W93, respectively) were synthesized according to procedures previously described (4). [3H]-1263W94 (14.9 Ci/mmol) was synthesized by Moravek Biochemicals, Inc. (Brea, Calif.). GCV triphosphate and the 1263W94 5′-mono- and triphosphates were prepared by the previously described chemical method (19).

[α-32P]deoxynucleoside triphosphates ([α-32P]dNTPs) were obtained from Amersham (Piscataway, N.J.). Cell media and reagents were obtained from Gibco-BRL (Grand Island, N.Y.), except as noted.

Cell and viral culture.

HCMV strain AD169 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.) and was the laboratory strain used in characterization of the antiviral activity of 1263W94. GCV-resistant recombinants of AD169 were derived from marker rescue experiments with GCV-resistant clinical isolates and wild-type AD169, as reported previously (1, 7, 13, 25). Ten HCMV clinical isolates were obtained from diverse geographical locations within the United States. The HCMV clinical isolates were recovered from immunocompromised patients, including organ transplant patients and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected patients who had not yet received therapy for HCMV infection. Human T-cell leukemia lines Molt-4, CEM, and CEM CD4+ and human B-cell leukemia line IM9 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Human diploid fibroblast cells (MRC-5 lung cells, embryonic kidney cells, and human foreskin cells) were from BioWhittaker (Walkersville, Md.). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and coronary artery smooth muscle cells (CASMC) were obtained from Clonetics (San Diego, Calif.). Clinical strains were used if they tested negative for the presence of mycoplasma by using the Gen Probe Mycoplasma Rapid Detection System (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.).

Monolayer cultures of human diploid fibroblast cells were grown at 37°C in Eagle minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with either 8 or 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone Laboratories, Logan, Utah), 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 U of penicillin G/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin sulfate/ml (designated MEM 8-1-1 with 8% FBS or MEM 2-1-1 with 2% FBS). Media for HUVEC and CASMC were obtained from Clonetics and cultured according to recommended protocols.

Determination of antiviral activity.

Assessment of antiviral activity and determination of 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) for 1263W94 and other antiviral compounds were made based on three methods of quantitation of virus: (i) measurement of viral plaque formation (plaque reduction assay), (ii) measurement of extracellular infectious virus in a single cycle of viral replication (yield reduction assay), and (iii) measurement of intracellular viral DNA by specific DNA-DNA hybridization after multiple cycles of viral replication. To define the dose-response curves for each antiviral compound assessed, up to eight concentrations of each compound were tested.

Plaque reduction assays were performed with both cell-free virus and cell-associated clinical strains on MRC-5 cells according to standard protocols (24). Plaques were counted by using a binocular microscope at magnifications of ×10 to ×70. IC50s were calculated from the data by using PROBIT, version 79.3 (SAS, Cary, N.C.).

For the virus yield reduction assay, MRC-5 cells were grown to confluence (1.1 × 105 cells/well) in 24-well plates, infected with cell-free virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ca. 1 and incubated in MEM 2-1-1 at 37°C in the presence or absence of drug. After 72 h, culture supernatants were removed, and limiting dilutions of virus in the culture supernatant were used to infect monolayers of MRC-5 cells. Inoculation media containing residual concentrations of drugs were removed after viral adsorption. Plaques were quantitated as described for the plaque reduction assay. The IC50 values were calculated by fitting viral yield as a function of drug concentration to the Hill equation by weighted linear regression (15, 20).

For assessment of antiviral activity by inhibition of viral DNA synthesis of laboratory strain AD169, 0.7 × 104 MRC-5 cells/well were grown for 3 days to confluence (∼2 × 104 cells/well) in 96-well plates. Medium was removed to leave 20 μl per well, and 150 PFU of AD169 in 25 μl of MEM 2-1-1 was added to each well, for an MOI of ca. 0.008. After a 10-min centrifugation at 1,500 rpm, plates were incubated at 37°C for 90 min to allow viral adsorption to occur, and 180 μl of MEM 2-1-1 containing no drug or containing specified concentrations of antiviral compounds was added to each well. For each antiviral compound investigated, a range of concentrations was chosen to bracket the expected IC50 value. Incubation was continued at 37°C for 6 to 8 days until viral controls without drug showed ∼100% cytopathic effect. Since nearly 99% of the cells were infected by virus produced during the first round of replication, measurement of viral DNA at the end of the second round of replication provides a measure of the antiviral effects of compounds regardless of their mechanism of action. For assessment of antiviral activity of various anti-HCMV compounds against clinical HCMV isolates in a DNA hybridization assay, cell monolayers were infected with cell-associated virus stocks of each clinical isolate corresponding to ca. 100 infectious centers (24).

In both cases, culture medium was then removed by aspiration, and cells were lysed by the addition of 50 μl of lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8; 50 mM EDTA; 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate; 0.1 mg of proteinase K/ml)/well and incubation for 1 to 2 h at 56°C. The lysate was extracted with phenol, and viral DNA in the resulting aqueous phase was measured by quantitative DNA hybridization as previously described (27). IC50 values were calculated by fitting viral DNA as a function of the drug concentration to the Hill equation as described above.

Selection of drug-resistant virus.

Laboratory strain AD169 was serially passaged in increasing concentrations of 2916W93, beginning with 4 μM 2916W93, approximately twice the IC50, and ending with 80 μM, a concentration higher than the IC90 value for 2916W93. Virus amplification was accomplished after cultures achieved maximum cytopathic effect by passage of either cell-associated or cell-free supernatant virus, depending upon the extent of virus infection and the integrity of the cell monolayer.

Virus that grew in 80 μM 2916W93 at passage 13 was purified by three cycles of plaque purification in the absence of 2916W93 selective pressure. The resulting virus strain, designated 2916rA, was compared with parent strain AD169 for the ability to replicate in the presence of benzimidazole compounds 1263W94, 2916W93, and BDCRB. GCV was included in the assays for comparison.

Marker rescue experiments.

High-molecular-weight DNA was isolated from virus pellets of strain 2916rA, and a cosmid library was constructed and screened for HCMV DNA by hybridization against defined fragments of HCMV as described previously (27). Marker rescue experiments were performed as previously described (27) with the cosmids and subfragments from 2916rA cotransfected with AD169 infectious DNA. After incubation in the absence of drug until maximum cytopathic effect was achieved, 250,000 PFU from each resulting recombinant pool were plated on MRC5 cells and incubated in the presence of 10 μM 1263W94. Incubation was at 34°C, which gave the optimum selective advantage to the resistant mutants. The supernatant virus yield was measured and the cell monolayer was resuspended and used as the inoculum for the second plating.

DNA sequence analysis.

The 2.25-kb DNA fragment encompassing the UL97 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified by PCR from genomic HCMV DNA isolated from wild-type strain AD169, the parent strain 2916rA, and the 2916rA-UL97rec virus. The primers used were CPT0 (5′-TCGACGACGCCGTCTA-3′) and CPTZ (5′-CAACCGTCACGTTCCGCG-3′). Sequencing reactions of PCR fragments from the UL97 ORF were performed with primers designed from the published sequence of HCMV AD169 (6) and standard protocols with the ABI 377 fluorescent DNA sequencer (PE Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Sequencing data were analyzing by using Sequencher DNA analysis software, version 3.0 (GeneCodes Corporation, Ann Arbor, Mich.).

pUL97 enzyme preparation and assay.

The baculovirus construct BVGSTUL97 (14) encoding the pUL97 protein kinase as a glutathione S-transferase fusion protein was generously provided by D. Coen. The protein was produced and purified exactly as described previously (14). The enzyme was assayed as described, except that sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels from autophosphorylation assays were quantitated after exposure to a phosphorimager screen by using ImageQuant software and, to determine histone phosphorylation, the final reaction mixture was mixed with 150 μl of 0.5% phosphoric acid and applied to a phosphocellulose filter (Millipore MAPHNB010). The filter was washed three times with 300 μl of 0.5% phosphoric acid and air dried. Then, 30 μl of Wallac Optiphase Supermix scintillation fluid was added, and the filter was counted in a Wallac Micro Beta scintillation counter. This filter-binding method reported both autophosphorylation and histone phosphorylation.

The pUL97 protein concentration used was 9 nM in the histone phosphorylation assays and 0.5 μM in the autophosphorylation assays. Reaction times and pUL97 concentrations were such that, in the histone phosphorylation assays, only 5% of the total filter-binding signal was due to autophosphorylation.

Effect of 1263W94 on HCMV DNA synthesis and maturation.

For these studies MRC-5 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at ∼5 × 104 cells/well and grown for 3 days in MEM 8-1-1 to confluence (∼1.1 × 105 cells/well). The cells were infected with AD169 in MEM 2-1-1 at an MOI ranging from 1 to 3 and incubated at 37°C for 90 min to allow viral adsorption. The unadsorbed virus was removed and replaced with 1 ml of MEM 2-1-1. To test the effect of compounds on viral DNA synthesis or maturation, 1263W94, BDCRB, or GCV was added to the medium at the concentrations indicated for each experiment.

For experiments examining DNA synthesis, HCMV-infected cells were treated with drug for 3 to 4 days, and viral DNA was isolated at various times and quantitated by DNA hybridization as described above. For experiments examining the effects of 1263W94 and BDCRB on viral DNA maturation, viral DNA was prepared at various times postinfection and subjected to contour-clamped homogenous electric field gel electrophoresis and DNA hybridization analysis of the proportions of monomeric and concatemeric viral DNA as previously described (27).

A novel method was developed to examine whether 1263W94 inhibited maturation of HCMV DNA, the step in DNA replication and processing affected by BDCRB. The “BDCRB wash-out” was a modification of the experiment described above investigating the effect of 1263W94 or BDCRB on viral DNA maturation. Cells were infected at an MOI of 1.0, and 20 μM BDCRB was added after adsorption. Infected cells were incubated for 4 days to allow maximum accumulation of newly synthesized concatemeric viral DNA. Medium containing BDCRB was then removed, and cultures were washed and refed with medium containing the compound to be tested or with drug-free or BDCRB-containing medium as negative and positive controls, respectively. After 24 h of further incubation, the effects of these inhibitors on the processing and packaging of viral DNA were measured. Since the effects of BDCRB are reversible (26, 27), its removal allows the accumulated concatemeric viral DNA to be rapidly processed to unit length genomes and packaged as infectious virus. Supernatant medium was sampled for measurement of the infectious virus titer. Viral DNA was prepared from the cell monolayers, and the proportions of monomeric and concatemeric viral DNA were measured as described above.

Isolation and assay of HCMV DNA polymerase.

HCMV DNA polymerase was partially purified from lysed HCMV-infected MRC-5 cells by centrifugation and dialysis, followed by anion-exchange chromatography by using a DEAE cellulose column (16). Assay mixtures and methods were the same as previously described (16). The activity of HCMV DNA polymerase was assessed in the presence of 100 μM concentrations of 1263W94, 1263W94-5′-monophosphate (1263W94-MP), or 1263W94-5′-triphosphate (1263W94-TP). Because benzimidazole ribosides could compete with one or more of the natural dNTPs, assays evaluating 1263W94 and the phosphorylated derivatives were performed in a series of four reactions, with each reaction having three dNTPs present at saturating conditions and the fourth dNTP present in a concentration at or near its Km.

Anabolism of 1263W94 in human fibroblast cells.

Confluent monolayers of MRC-5 cells in 162-cm2 flasks, with ca. 107 cells per flask, were mock infected or infected with 2 × 107 PFU of HCMV AD169. High-pressure liquid chromatography-purified [3H]-labeled 1263W94 (diluted to 1 Ci/mmol) in dimethyl sulfoxide was added to the MEM 2-1-1 at a final concentration of 0.5 μM. At the indicated times after infection the cells were washed and extracted by suspension in 11 ml of ice-cold 80% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in water at −70°C overnight (3). The cells were removed by centrifugation, the supernatant liquid was evaporated to dryness, and the extract was dissolved in water. 1263W94 and its potential anabolites were separated on a Partisil 5 SAX RacII anion-exchange column (Whatman, Inc., Clifton, N.J.) at pH 5.0 with a gradient of KCl. Because 1263W94 was not well resolved from the monophosphate form, the samples were also analyzed on a μBondapak C18 column (Waters Corp., Milford, Mass.) at pH 3.5 with an acetonitrile gradient. In both cases fractions were collected, scintillation fluid was added, and the amount of 3H was counted.

Cytotoxicity assays.

Cytotoxicity of 1263W94, BDCRB, and GCV to bone marrow progenitor cells was determined by evaluating growth inhibition (i.e., CFU of granulocytes-macrophages and burst-forming unit-erythroid [see Table 8]), as previously described (11). Cytotoxicity to human leukemia cell lines was determined as previously described (22).

TABLE 8.

Cytotoxicity of benzimidazole ribosides and GCV to primary human bone marrow progenitor cellsa

| Test compound | Mean IC50 (μM) ± SEM

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CFU-GM | BFU-E | No. of determinations (no. of donors) | |

| 1263W94 | 90 ± 4 | 88 ± 4 | 4 (4) |

| BDCRB | 110 ± 18 | 90 ± 10 | 9 (9) |

| GCV | 15 ± 3 | 39 ± 10 | 18 (15) |

Data for 1263W94 were previously reported by Chan et al. (5). CFU-GM, CFU of granulocytes-macrophages; BFU-E, burst-forming unit-erythroid.

RESULTS

Antiviral activity of benzimidazole compounds.

The antiviral activity of 1263W94 against HCMV strain AD169 grown on MRC-5 lung fibroblast cells is compared to those of other related benzimidazole compounds and of GCV in Table 1. In the benzimidazole series, the most potent compound by DNA hybridization was 1263W94, with a mean IC50 by DNA hybridization ∼4-fold lower than that for GCV. The relative ranking of antiviral potency of the compounds in the series was similar in each of the three antiviral assays employed.

TABLE 1.

Sensitivity of HCMV strain AD169 to benzimidazole ribosides and GCV in MRC-5 lung fibroblast cells

| Test compound

|

Mean IC50 (μM) ± SEMa as determined by:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Benzimidazole 2-substituent | Ribose configuration | DNA hybridization | Plaque reduction | Yield reduction |

| 1263W94 | 2-Isopropylamino | l | 0.12 ± 0.01 (71) | 0.54 ± 0.05 (10) | 0.06 ± 0.018 (4) |

| 3322W93 | 2-Isopropylamino | d | 2.3 ± 0.5 (3) | 7.5 (1) | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| 3858U92 | 2-Bromo | l | 0.9 ± 0.2 (5) | 1.3 ± 0.7 (3) | 0.5 ± 0.06 |

| BDCRB | 2-Bromo | d | 0.54 ± 0.08 (20) | 0.31 ± 0.06 (6) | 0.018 ± 0.001 |

| GCV | NAb | Acyclic | 0.53 ± 0.04 (117) | 6.3 ± 0.7 (6) | 0.30 ± 0.15 (2) |

The number of experiments is shown in parentheses.

NA, not applicable.

Activity of 1263W94 and GCV against HCMV AD169 was also measured by the yield reduction assay in HUVEC and CASMC. 1263W94 was active at submicromolar concentrations and was ∼5-fold more active than GCV. In experiments performed in triplicate, the mean IC50 values (± the standard error [SE]) for 1263W94 in CASMC and HUVEC were 0.08 ± 0.03 and <0.01 μM (the lowest concentration tested), respectively, compared to the mean IC50 values of 0.52 ± 0.35 and 1.08 ± 0.22 μM for GCV.

To verify that the antiviral activity of 1263W94 was not restricted to the laboratory strain AD169, the antiviral activity of 1263W94 was assessed against 10 clinical isolates of HCMV. All were sensitive to 1263W94, with IC50s obtained in the DNA hybridization assays that ranged from 0.03 to 0.13 μM for 1263W94 and from 0.15 to 1.10 μM for GCV. Similar results were obtained for these 10 clinical strains in the plaque reduction assays, with IC50s ranging from 0.12 to 0.56 μM for 1263W94 and from 0.80 to 7.00 μM for GCV (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Susceptibility of HCMV clinical isolates to 1263W94 and GCVa

| Virus strain | Mean IC50 (μM) as determined by:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA hybridization assay

|

Plaque reduction assay

|

|||

| 1263W94 | GCV | 1263W94 | GCV | |

| AD169 | 0.04 | 0.40 | 0.97 | 4.30 |

| C8301 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 1.10 |

| C8501 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 0.34 | 1.00 |

| C8910 | 0.12 | 0.70 | 0.19 | 1.40 |

| C9207 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.44 | 6.70 |

| C8303 | 0.09 | 0.80 | 0.54 | 0.80 |

| C8302 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 2.70 |

| C8803 | 0.13 | 0.70 | 0.21 | 3.40 |

| C8912 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 0.21 | 2.60 |

| C9003 | 0.12 | 1.10 | 0.56 | 1.00 |

| C9213 | 0.04 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 7.00 |

Assays were performed with HCMV-infected MRC-5 lung fibroblast cells. Values represent the average of two independent determinations. The standard error of the mean was <30% of the value shown in all assays.

Activities of 1263W94, GCV, and BDCRB against GCV- or BDCRB-resistant strains were assessed by using the multicycle DNA hybridization assay. The mutations conferring resistance to GCV had previously been mapped to UL97 (1, 7, 13, 25) and to viral DNA polymerase (2), and the BDCRB-resistant mutations to UL89 in the HCMV genome (27). The strains tested included recombinant strains in which the GCV resistance mutations were recombined into an AD169 background. As shown in Table 3, there were no significant differences in IC50s of 1263W94 among seven of the eight strains tested. An eighth strain, 2916rA, had been selected for resistance to 2916W93 (see below). Notably, these strains that were resistant to BDCRB or to GCV retained sensitivity to 1263W94.

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity of drug-resistant strains of HCMV to benzimidazole ribosides and GCV, as determined by a DNA hybridization assay

| Virus strain | Mean IC50 ± SEM (μM)a

|

Altered gene | Amino acid change (s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1263W94 | GCV | BDCRB | |||

| AD169 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.31 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | NAb | NA |

| 8805rec1 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 2 ± 1 | UL97 | Met460Val |

| 9330rec5 | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | UL97 | His520Glu |

| 8702rec2 | NDd | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 0.75 ± 0.3 | UL97 | Ala594Val |

| 9219rec7 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.8 | UL97 | Leu595del |

| XbaF.4 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | UL97 | AlaAlaCysArg593del |

| 4955rec | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.7 ± 0.07 | ND | polc | Thr700Ala |

| 1038rB | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.06 | >20 | UL89 | Asp344Glu and Ala355Val |

| 2916rAe | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.12 | UL97 | Leu397Arg |

That is, the mean values based on a minimum of three independent determinations.

NA, not applicable.

pol, polymerase.

ND, not determined.

DNA sequencing of the entire virus was not performed. The sequence change in the UL97 ORF conferred resistance to 1263W94 when transferred into wild-type strain AD169.

Isolation of drug-resistant virus.

In an effort to confirm that 1263W94 inhibits HCMV through a specific antiviral mechanism that targets a viral gene or gene product, we selected HCMV specifically resistant to 1263W94. Strain AD169 was serially passaged in increasing concentrations of 1263W94 or of the closely related carbocyclic analog 2916W93. The selective pressure resulted in the enrichment of several viral populations capable of variable growth in the presence of the drugs. Plaque purification of the most growth-competent strains selected with 2916W93 yielded strain 2916rA, which clearly showed a drug-resistant phenotype. Cross-resistance was tested by DNA hybridization assays, which showed strain 2916rA to be sensitive to both BDCRB and GCV (Table 3). This finding confirms results presented in Gudmundsson et al. (12). Both the BDCRB-resistant strain 1038r and the GCV-resistant XbaF4 were sensitive to 1263W94.

A cosmid library was constructed from strain 2916rA, and a fragment identified as S7 was shown to confer resistance to 1263W94 in marker transfer experiments. Analysis of fragment S7 showed that it contained HindIII fragments P, R, S, and T (6), and resistance to 1263W94 was associated only with HindIII fragment S (Table 4). At the same time that these results were obtained, we found that 1263W94 was a potent inhibitor of the HCMV UL97 protein kinase (see below), which is encoded by one of the ORFs on HindIII fragment S. Consequently, the genetic mapping then focused on the UL97 ORF. The 2.25-kb PCR fragment designated PCR-UL97-2916rA encompassing the UL97 ORF and defined by primers CPTZ and CPTO (see Materials and Methods) was recombined with wild-type strain AD169, and the recombinant progeny virus was found to be resistant to 1263W94 (Table 4). DNA sequencing of the 2.25-kb fragment identified a single nucleotide substitution, T1190G, which would result in a predicted amino acid substitution of Leu to Arg at position 397 of the UL97 polypeptide.

TABLE 4.

Virus yields in the presence of 10 μM 1263W94 after recombinant pools from marker rescue of HCMV AD169 were plated

| DNA fragment from 2916rA recombined with AD169 | Virus yield (PFU/ml)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Plating 1 | Plating 2 | |

| None | 100 | 300 |

| PCR-UL97-2916rA | 60 | 212,300 |

| S7 | 10,000 | 37,500 |

| S7 8.5-kb HindIII | 2,400 | 17,500 |

| S7 HindIII-P | 120 | 1,600 |

| S7 HindIII-R | 80 | 1,000 |

| S7 HindIII-S | 6,500 | 2,220,000 |

| S7 HindIII-T | 120 | 11,500 |

After plaque purification the recombinant virus, now designated 2916rA-UL97rec, was compared to its parents, the wild-type AD169 and the 2916rA viruses, in a multicycle DNA hybridization assay for resistance phenotype. The IC50s for 1263W94 were 0.056 ± 0.01 μM for AD169, 0.7 ± 0.3 μM for 2916rA, and 0.9 ± 0.02 μM for 2916rA-UL97rec. These data suggest that the mutation in UL97 is sufficient to account for the observed resistance of 2916rA to 1263W94.

1263W94 inhibits wild-type UL97 protein kinase but not UL97 kinase from the 2916rA virus.

1263W94 was a potent inhibitor of histone phosphorylation catalyzed by wild-type pUL97 in vitro, with an IC50 of 3 nM, close to one-half of the concentration of active enzyme. In contrast, the IC50 of 1263W94 for histone phosphorylation catalyzed by the UL97 kinase with the Leu397Arg mutation of the 2916rA virus was increased 20,000-fold to 60 μM. IC50 determinations were not performed for autophosphorylation; however, wild-type pUL97 autophosphorylation was inhibited 99% by 1 μM 1263W94. Autophosphorylation of pUL97 from the 2916rA virus was inhibited by <5% by 1 μM 1263W94.

1263W94 inhibits HCMV DNA synthesis in infected cells but does not directly inhibit HCMV DNA polymerase.

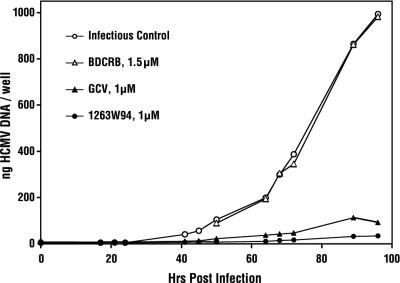

Viral DNA was measured in HCMV-infected MRC-5 cells during a single-cycle infection in the presence or absence of the antiviral drugs BDCRB, 1263W94, or GCV (Fig. 2). Synthesis of HCMV DNA was unaffected by the presence of 1.5 μM BDCRB, as previously reported (27). However, the continuous presence of 1 μM 1263W94 or GCV, viral DNA synthesis was reduced to <10% of control levels. These measurements were repeated with a range of concentrations of 1263W94 from 0.025 to 0.5 μM and of GCV from 0.5 to 5 μM, permitting the calculation of IC50s for inhibition of DNA synthesis by 1263W94 and GCV at different times postinfection. At 72 h postinfection the IC50 was 0.19 ± 0.07 μM for 1263W94 and 1.9 ± 0.3 μM for GCV; at 92 h postinfection the IC50 was 0.11 ± 0.01 μM for 1263W94 and 0.8 ± 0.13 μM for GCV. The IC50s for inhibition of HCMV DNA synthesis by 1263W94 and GCV in a single cycle of viral replication are similar to those measured for viral replication by any of the standard methods employed. These observations were extended by comparing the inhibition by 1263W94, BDCRB, GCV, and phosphonoformic acid (PFA) (10) of HCMV DNA synthesis and of viral yield at 72 h postinfection (Table 5). For GCV and PFA, the IC50s for DNA synthesis were two- to threefold higher than the IC50s for yield reduction. Similarly, for 1263W94 the IC50s for DNA synthesis were four- to fivefold higher than those for yield reduction; in contrast, for BDCRB the IC50s for DNA synthesis were >750-fold higher than those for yield reduction.

FIG. 2.

Effects of 1263W94, GCV, and BDCRB on HCMV DNA synthesis during a single-cycle infection of MRC-5 cells.

TABLE 5.

Relative inhibition at 72 h postinfection of virus DNA synthesis and virus yield by 1263W94 and other compounds in a single-cycle infection

| Test compound | Mean IC50 ± SEM (μM)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| DNA synthesis | Virus yield | |

| 1263W94 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.018 |

| BDCRB | >25 | 0.03 ± 0.005 |

| GCV | 0.95 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.15 |

| PFA | 79 ± 11 | 33 ± 1 |

That is, of at least three determinations.

To investigate whether inhibition of viral DNA synthesis by 1263W94 resulted from a direct effect on viral DNA polymerase, HCMV DNA polymerase activity was assessed in the presence of 1263W94, 1263W94-MP, or 1263W94-TP. No significant inhibition of HCMV DNA polymerase was observed in the presence of 100 μM concentrations of any of the compounds tested (Table 6). GCV triphosphate inhibited this HCMV polymerase preparation with a Ki value of 0.43 μM. Thus, 1263W94 inhibits viral DNA synthesis but by a mechanism different from that of GCV.

TABLE 6.

Effect of 1263W94 and phosphorylated derivatives on the activity of HCMV DNA polymerase

| Inhibitor | HCMV DNA polymerase (% activity by limiting dNTP)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dATP | dCTP | dGTP | TTP | |

| 1263W94 | 91 | 96 | 90 | 91 |

| 1263W94-MP | 84 | 96 | 101 | 102 |

| 1263W94-TP | 86 | 89 | 100 | 108 |

Phosphorylation of 1263W94 to 1263W94-MP or 1263W94-TP does not occur in uninfected or HCMV-infected human fibroblasts.

To determine whether human fibroblast cells produce phosphorylated anabolites of 1263W94, both uninfected and HCMV-infected MRC-5 cells were cultured in the presence of radiolabeled 1263W94. Anion-exchange and reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography were used to examine cell extracts prepared at 0, 48, and 96 h postinfection. The sensitivities of the methods employed were such that intracellular concentrations of as little as 10 nM would have been detected. No phosphorylated anabolites of 1263W94 were observed in either uninfected or HCMV-infected cells (data not shown).

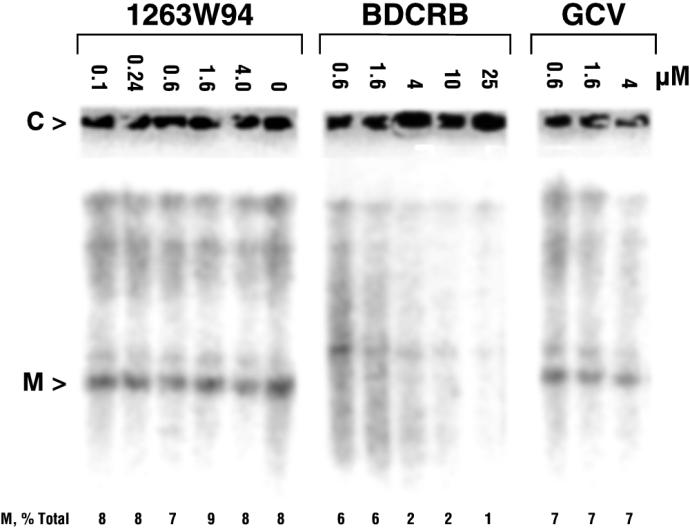

Effect of 1263W94 on HCMV DNA maturation.

Previous reports demonstrated that BDCRB blocks HCMV replication by inhibiting the maturational cleavage of high-molecular-weight viral DNA concatemers (27), an obligatory process, conserved in all herpesviruses, that occurs in conjunction with viral DNA packaging (28). To determine whether 1263W94 inhibits this process, the accumulation of high-molecular-weight viral DNA in HCMV-infected cells was measured in the presence or absence of 1263W94 (Fig. 3). The total amount of HCMV DNA synthesized decreased with increasing concentrations of 1263W94, but there were only minor changes in the extent of conversion of the precursor HCMV concatemers to mature unit-length viral DNA. In contrast, BDCRB did not inhibit the total amount of HCMV DNA synthesized but clearly inhibited the conversion of HCMV concatemers to monomers in a dose-dependent manner.

FIG. 3.

Synthesis and processing of high-molecular-weight HCMV DNA in HCMV-infected cells in the presence or absence of 1263W94, BDCRB, and GCV. Calculations from integrated band intensities are shown below the figure. Abbreviations: M, monomeric viral DNA; C, concatemeric viral DNA.

The “BDCRB washout” method was also employed to examine more directly the effects of 1263W94 on DNA concatemer cleavage. As shown in Fig. 4 and as quantified in Table 7, the exposure of infected cells to 1263W94 only after removal of the BDCRB-mediated block in viral maturation did not prevent subsequent production of mature HCMV DNA and infectious virus. BDCRB inhibited both measures of viral maturation, with IC50 calculated to be 0.1 μM.

FIG. 4.

“BDCRB washout” experiment for determining the effects of 1263W94, BDCRB, and GCV on the processing of concatemeric HCMV DNA that had accumulated during 96 h in the presence of BDCRB. Calculations from integrated band intensities are shown below the figure. Abbreviations: M, monomeric viral DNA; C, concatemeric viral DNA.

TABLE 7.

Effect of drug treatment on HCMV DNA maturation and virus yield after reversal of BDCRB treatment

| Test compound | IC50 ± SEM (μM)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| DNA maturation | Virus yield | |

| 1263W94 | 27 ± 7 | 18 ± 0.5 |

| BDCRB | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| GCV | >25 | >25 |

Cytotoxicity results.

Like other benzimidazoles (21), 1263W94 was significantly less toxic to human bone marrow progenitor cells than was GCV (Table 8). Growth inhibition studies with 1263W94 were also conducted in three human T-cell leukemia lines (Molt-4, CEM, and CEM-CD4+) and one human B-cell leukemia line (IM9). The IC50s ranged from 35 μM for MOLT-4 cells to 72 μM for CEM-CD4+ cells (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The benzimidazole ribosides are a series of compounds with potent antiviral activity against HCMV. The lead compound in the series, BDCRB, proved to be disappointing due to its rapid metabolism to the inactive and toxic aglycone (8). In an effort to discover metabolically stable derivatives with the anti-HCMV activity of BDCRB, various d- and l-riboside analogs of BDCRB were synthesized. Synthesis and analysis of a number of riboside derivatives in the benzimidazole series has led to a preliminary description of the structure activity relationship of the series. The compounds described here represent the 2′-substituted d- and l-riboside analogs that were the most thoroughly characterized.

In the benzimidazole series tested, both the biologically unnatural l-riboside derivatives and the d-riboside derivatives were potent antiviral agents against laboratory HCMV strains in vitro. The l-riboside of BDCRB, 3858W92, showed an anti-HCMV activity but was less potent than BDCRB (Table 1). Substitution of a 2′-isopropyl moiety for the 2′-bromo moiety of BDCRB and 3858W92 produced the 2′-isopropylamino d-riboside analog 3322W93 and the corresponding l-riboside 1263W94. The d-riboside 3322W93 was somewhat less potent than BDCRB. In contrast, 1263W94 exhibited an anti-HCMV potency comparable to that of BDCRB in each of the viral assays performed, with IC50s 4- to 10-fold lower than those of GCV. Furthermore, 1263W94 was highly active against GCV- or PFA-resistant HCMV strains and against a panel of HCMV clinical isolates from different geographical areas of the United States.

The d-riboside compounds in the benzimidazole series, BDCRB and 3322W93, do not inhibit viral DNA synthesis but instead inhibit viral replication at the stage of viral DNA maturation, when the viral DNA concatemers are processed to form unit length DNA for viral packaging (27). An unexpected finding in our studies was that the antiviral activity of 1263W94 stems from a different mechanism of action from that of BDCRB, the parent compound. As shown by direct analysis (Fig. 3) and by the “BDCRB washout” experiment (Fig. 4), incubation of HCMV-infected cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of 1263W94 does not significantly inhibit processing of concatemeric DNA. As shown in Fig. 2 and Table 5, 1263W94 and GCV both inhibit viral DNA synthesis in a single cycle assay, and the ratios of the IC50s for DNA synthesis and viral yield are similar for both compounds. Like GCV, 1263W94 inhibits viral DNA replication, but it does so by a different mechanism of action. This conclusion is consistent with the lack of cross-resistance of the 1263W94- and GCV-resistant viral strains examined in this study.

The antiviral activity of GCV results from incorporation of the triphosphorylated metabolite of GCV into the growing DNA chain as GCV monophosphate (18). The mechanisms of antiviral action of the benzimidazole compounds differ from that of GCV, since they are active against viral strains resistant to GCV. Unlike GCV (18), 1263W94 is not phosphorylated in infected cells, nor does the compound itself nor any of its synthetic phosphorylated derivatives inhibit HCMV DNA polymerase. The antiviral activity of 1263W94 results from a novel mechanism of action, one different from that of both GCV and the parent compound, BDCRB.

We show here that resistance to 1263W94 in the HCMV mutant 2916rA maps to the UL97 ORF and that 1263W94 is a potent inhibitor of the UL97 protein kinase of HCMV. Wolf et al. (29) have recently reported that a UL97 deletion mutant of HCMV shows a reduction in DNA synthesis comparable to that described here in the presence of 1263W94. It is probable, therefore, that the primary target of 1263W94 is the UL97 kinase, but as yet it is not known how inhibition of the kinase results in inhibition of viral replication.

Wolf et al. also presented the results of BDCRB washout experiments showing that the UL97 deletion mutant was defective in capsid assembly, a finding inconsistent with those presented here (29). Since deletion and inhibition of an enzyme may not be exactly equivalent, the inconsistency may be more apparent than real. In any case, our data cannot exclude the possibility that pUL97 is also involved in late stages of viral replication. Indeed, data presented in Fig. 3 indicate that 1263W94 at higher concentrations reduces the formation of monomeric DNA. The lack of measurable effect of 1263W94 on DNA concatemer maturation in the BDCRB washout experiments (Fig. 4) could indicate that the effects of 1263W94 on monomer formation, presumably mediated through inhibition of pUL97, occur earlier in replication.

Others have observed less-potent inhibition of HCMV DNA replication by 1263W94 than shown here (D. Coen, unpublished data). Such differences in experimental observations on the role of pUL97 in viral replication could result from different experimental conditions, particularly in the physiological state of the infected cells resulting from differences in culture conditions. All of the experiments reported here were carried out with fully confluent, quiescent cells, conditions that yielded the most reproducible replication of HCMV strain AD169.

In vitro assays indicate that 1263W94 shows not only a potency advantage over GCV but also a selectivity advantage. One of the side effects associated with prolonged GCV therapy is bone marrow toxicity, resulting in leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and bone marrow hypoplasia (9). Previous work had shown BDCRB and certain related benzimidazole nucleosides to be less toxic to bone marrow cells in vitro than GCV (21). Our data with 1263W94 extended these results, showing that both benzimidazole compounds have low cytotoxicity, reducing the possibility of bone marrow suppression with therapy.

In conclusion, we have shown that 1263W94 is a novel, selective, and potent anti-HCMV compound with a novel mechanism of action. The mechanism has proven relevant to antiviral therapy, since 1263W94 (maribavir) has recently shown potent reduction of viral load in a phase I-II clinical study in HIV-infected patients (J. Lalezari, J. Aberg, L. Wang, M. Wire, R. Miner, W. Snowden, C. Talarico, S. Shaw, M. Jacobson, and W. Drew, unpublished data).

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Hopson and Joseph Paisley for technical assistance with the bone marrow progenitor cytotoxicity assays, Ernest Dark for technical assistance with the human leukemia cell line cytotoxicity assays, and Barbara J. Rutledge for assistance with writing and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Mary Lou Hemphill.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldanti, F., E. Silini, A. Sarasini, C. Talarico, S. Stanat, K. Biron, M. Furione, F. Bono, G. Palu, and G. Gerna. 1995. A three-nucleotide deletion in the UL97 open reading frame is responsible for the ganciclovir resistance of a human cytomegalovirus clinical isolate. J. Virol. 69:796-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldanti, F., M. Underwood, S. Stanat, K. Biron, S. Chou, A. Sarasini, E. Silini, and G. Gerna. 1996. Single amino acid changes in the DNA polymerase confer foscarnet resistance and slow-growth phenotype, while mutations in the UL97-encoded phosphotransferase confer ganciclovir resistance in three double-resistant human cytomegalovirus strains recovered from patients with AIDS. J. Virol. 70:1390-1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanchard, J. 1981. Evaluation of the relative efficacy of various techniques for deproteinizing plasma samples prior to high-performance liquid chromatographic analysis. J. Chromatogr. 226:455-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamberlain, S., S. Daluge, and G. Koszalka. June 2000. Antiviral benzimidazole nucleoside analogues and a method for their preparation. U.S. patent 6077832.

- 5.Chan, J., S. Chamberlain, K. Biron, M. Davis, R. Harvey, D. Selleseth, R. Dornsife, E. Dark, L. Frick, L. Townsend, J. Drach, and G. Koszalka. 2000. Synthesis and evaluation of a series of 2′-deoxy analogues of the antiviral agent 5,6-dichloro-2-isopropylamino-1-(β-l-ribofuranosyl)-1H-benzimidazole (1263W94). Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 19:101-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chee, M., A. Bankier, S. Beck, R. Bohni, C. Brown, R. Cerny, T. Hornshell, C. Hutchison III, T. Kouzarides, J. Martignetti, E. Preddie, S. Satchwell, P. Tomlinson, K. Weston, and B. Barrell. 1990. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 154:125-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou, S., A. Erice, M. C. Jordan, G. Vercellotti, K. Michels, C. Talarico, S. Stanat, and K. Biron. 1995. Analysis of the UL97 phosphotransferase coding sequence in clinical isolates and identification of mutations conferring ganciclovir resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 171:576-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chulay, J., K. Biron, L. Want, M. Underwood, S. Chamberlain, L. Frick, S. Good, M. Davis, R. Harvey, L. Townsend, J. Drach, and G. Koszalka. 1999. Development of novel benzimdazole riboside compounds for treatment of cytomegalovirus disease, p. 129-134. In J. Mills, P. Volberding, and L. Corey (ed.), Antiviral therapy 5: new directions for clinical applications and research. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Crumpacker, C. 1996. Ganciclovir. New Engl. J. Med. 335:721-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Clercq, E. 1997. In search of a selective antiviral chemotherapy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:674-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dornsife, R., M. St Clair, A. Huang, T. Panella, G. Koszalka, C. Burns, and D. Averett. 1991. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus synergism by zidovudine (3′-azidothymidine) and didanosine (dideoxyinosine) contrasts with their additive inhibition of normal human marrow progenitor cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:322-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gudmundsson, K., J. Tidwell, N. Lippa, G. Koszalka, N. van Draanen, R. Ptak, J. Drach, and L. Townsend. 2000. Synthesis and antiviral evaluation of halogenated β-d- and -l-erythrofuranosylbenzimidazoles. J. Med. Chem. 43:2464-2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanson, M., L. Preheim, S. Chou, C. Talarico, K. Biron, and A. Erice. 1995. Novel mutation in the UL97 gene of a clinical cytomegalovirus strain conferring resistance to ganciclovir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1204-1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He, Z., Y.-S. He, Y. Kim, L. Chu, C. Ohmstede, K. Biron, and D. Coen. 1997. The human cytomegalovirus UL97 protein is a protein kinase that autophosphorylates on serines and threonines. J. Virol. 71:405-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill, A. 1910. The possible effects of the aggregation of the molecules of haemoglobin on its dissociation curves. J. Physiol. 40:4-8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang, E. 1975. Human cytomegalovirus. III. Virus-induced DNA polymerase. J. Virol. 16:298-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krosky, P., M. Underwood, S. Turk, K. Feng, R. Jain, R. Ptak, A. Westerman, K. Biron, L. Townsend, and J. Drach. 1998. Resistance of human cytomegalovirus to benzimidazole ribonucleosides maps to two open reading frames: UL89 and UL56. J. Virol. 72:4721-4728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin, J., C. Dvorak, D. Smee, T. Matthews, and J. Verheyden. 1983. 9-[(1,3-Dihydroxy-2-propoxy)methyl]guanine: a new potent and selective antiherpes agent. J. Med. Chem. 26:759-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGuigan, C., A. Perry, C. Yarnold, P. Sutton, D. Lowe, W. Miller, S. Rahim, and M. Slater. 1998. Synthesis and evaluation of some masked phosphate esters of the anti-herpesvirus drug 882C (netivudine) as potential antiviral agents. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 9:233-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monod, J., J.-P. Changeux, and F. Jacob. 1963. Allosteric proteins and cellular control systems. J. Mol. Biol. 6:306-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nassiri, M., S. Emerson, R. Devivar, L. Townsend, J. Drach, and R. Taichman. 1996. Comparison of benzimidazole nucleosides and ganciclovir on the in vitro proliferation and colony formation of human bone marrow progenitor cells. Br. J. Haematol. 93:273-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prus, K., D. Averett, and T. Zimmerman. 1990. Transport and metabolism of 9-β-d-arabinofuranosylguanine in a human T-lymphoblastoid cell line: nitrobenzylthioinosine-sensitive and -insensitive influx. Cancer Res. 50:1817-1821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sia, I., and R. Patel. 2000. New strategies for prevention and therapy of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in solid-organ transplant recipients. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:83-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanat, S., J. Reardon, A. Erice, M. Jordan, W. Drew, and K. Biron. 1991. Ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus clinical isolates: mode of resistance to ganciclovir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:2191-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan, V., C. Talarico, S. Stanat, M. Davis, D. Coen, and K. Biron. 1992. A protein kinase homologue controls phosphorylation of ganciclovir in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Nature 358:162-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Townsend, L., R. Devivar, S. Turk, M. Nassiri, and J. Drach. 1995. Design, synthesis, and antiviral activity of certain 2,5,6-trihalo-1-(β-d-ribofuranosyl)benzimidazoles. J. Med. Chem. 38:4098-4105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Underwood, M., R. Harvey, S. Stanat, M. Hemphill, T. Miller, J. Drach, L. Townsend, and K. Biron. 1998. Inhibition of human cytomegalovirus DNA maturation by a benzimidazole ribonucleoside is mediated through the UL89 gene product. J. Virol. 72:717-725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vlazny, D., A. Kwong, and N. Frenkel. 1982. Site-specific cleavage/packaging of herpes simplex virus DNA and the selective maturation of nucleocapsids containing full-length viral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:1423-1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf, D., C. Courcelle, M. Prichard, and E. Mocarski. 2001. Distinct and separate roles for herpesvirus-conserved UL97 kinase in cytomegalovirus DNA synthesis and encapsidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:1895-1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zou, R., E. Kawashima, G. Freeman, G. Koszalka, J. Drach, and L. Townsend. 2000. Design, synthesis, and antiviral evaluation of 2-deoxy-d-ribosides of substituted benzimidazoles as potential agents for human cytomegalovirus infections. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 19:125-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]