Abstract

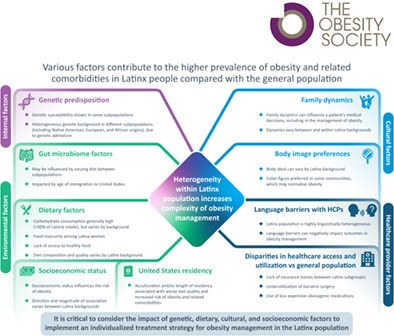

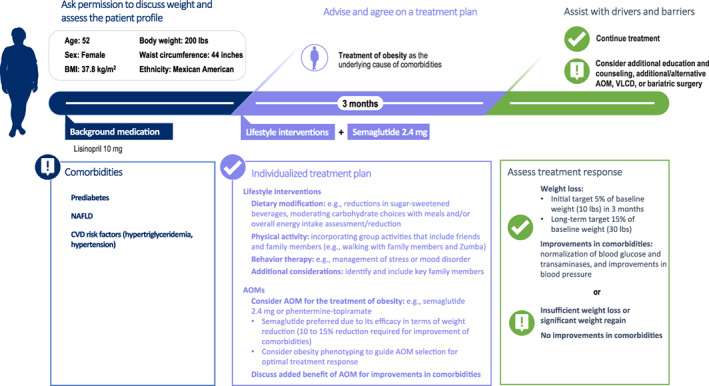

Obesity is a serious, chronic disease that is associated with a range of adiposity‐based comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. In the United States, obesity is a public health crisis, affecting more than 40% of the population. Obesity disproportionately affects Latinx people, who have a higher prevalence of obesity and related comorbidities (such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease) compared with the general population. Many factors, including genetic predisposition, environmental factors, traditional calorie‐dense Latinx diets, family dynamics, and differences in socioeconomic status, contribute to the increased prevalence and complexity of treating obesity in the Latinx population. Additionally, significant heterogeneity within the Latinx population and disparities in health care access and utilization between Latinx people and the general population add to the challenge of obesity management. Culturally tailored interventions have been successful for managing obesity and related comorbidities in Latinx people. Antiobesity medications and bariatric surgery are also important options for obesity treatment in Latinx people. As highlighted in this review, when managing obesity in the Latinx population, it is critical to consider the impact of genetic, dietary, cultural, and socioeconomic factors, in order to implement an individualized treatment strategy.

Study Importance.

What is already known?

Obesity is a chronic disease with complex etiology and risk factors, usually requiring long‐term lifestyle interventions, medications, and/or bariatric surgery.

In the United States, obesity disproportionately affects Latinx people, who have a higher prevalence of obesity and related comorbidities compared with the general population.

What does this review add?

This review highlights that the Latinx population is highly heterogeneous in terms of genetics, diet, language, and culture; therefore, individualized obesity care is critical to improve outcomes.

Key to successful management of obesity in the Latinx population is the development of culturally sensitive intervention strategies, ideally including bilingual and bicultural staff, adjusting interventions to suit Latinx diets, and encouraging the participation of key family members.

How might these results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice?

This review emphasizes the need for individualized care in Latinx people with obesity, as the population is highly heterogeneous in terms of genetics, diet, language, and culture.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a complex disease with serious health consequences, and it often requires medical interventions for clinically meaningful weight loss and lifelong management for weight maintenance. Defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥30.0 kg/m2, obesity is a growing public health crisis in the United States. In the National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHANES) 2017‐2018, 42.4% of adults in the United States met the criteria for obesity [1]. The prevalence of obesity varies by racial or ethnic background, with a higher prevalence in Hispanic/Latinx (hereafter referred to as Latinx) people compared with the general population.

Among Latinx and Mexican American populations, 44.8% and 50.4%, respectively, met the criteria for obesity in 2017‐2018, compared with 42.2% of the non‐Latinx White population [1]. The disproportionate risk of obesity in Latinx people is mirrored by a greater impact of obesity on health in this population. Obesity‐related comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes (T2D), and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), occur more frequently in Latinx people versus non‐Latinx White people [2, 3]. Furthermore, there is a higher prevalence of T2D at a lower BMI for Latinx people compared with non‐Latinx White people, affecting 25.6% versus 16.4%, respectively, of those with class 1 obesity (BMI 30.0‐34.9 kg/m2) [4]. Because of the heterogeneity in genetic, cultural, and lifestyle factors across the Latinx population [5, 6], tailored obesity programs that take these differences into account are key.

This manuscript reviews the impact of obesity on Latinx people and describes the key challenges and nuances when managing obesity in this population. Practical guidance for health care providers on how these challenges can be overcome is also provided.

LITERATURE SEARCH

A narrative literature search was conducted on January 22, 2021. Search terms related to ethnicity (Hispanic* OR Latin* OR ethnic*), background (Mexic* OR Guatemala* OR Colombia* OR Salvador* OR Cuba* OR Dominican OR Central OR Latin* OR Puerto Ric* OR Caribbean), location (America* OR States), obesity (obese OR obesity OR overweight OR “weight loss”), and topics of interest (prevalence OR etiology OR barrier* OR disparit* OR comorbidit* OR risk*).

The Medline database was searched using a combination of these key words, with results limited to 2010 to 2021 and English language. The articles were reviewed for relevance based on the title and abstract.

Additional references were identified from the bibliographies of retrieved articles, through additional targeted searches, and through author suggestions.

DISCUSSION

Pathophysiology of obesity

International societies recognize obesity as an adiposity‐based chronic disease, characterized by altered quantity, distribution, and/or function of adipose tissue that leads to disease [7].

The pathogenesis of obesity involves disordered regulation of gut–brain communication in the context of an obesogenic environment. After eating, people with obesity have reduced suppression of ghrelin and lower circulating levels of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 and peptide YY (PYY) compared with people with a healthy weight [8, 9]. As ghrelin stimulates appetite, and glucagon‐like peptide‐1 and PYY suppress appetite [8, 9], these disordered signals may result in greater food intake to maintain higher levels of adiposity.

Following weight loss, long‐term changes occur in these mediators of appetite and homeostatic body weight regulation [10]. Increased ghrelin and decreased PYY levels persist for more than 1 year after weight loss [10]. In addition, weight loss leads to physiologic adaptations that reduce energy expenditure, often including a reduced basal metabolic rate, which promote weight regain and make weight maintenance difficult [11]. Through these maladaptive responses, “obesity protects obesity” by resisting weight loss and promoting recurrence of overweight.

Burden of obesity in the Latinx population

The prevalence of multiple comorbidities, including CVD, T2D, NAFLD, and dyslipidemia, is elevated in the Latinx population compared with the non‐Latinx White population [2, 3, 12, 13].

NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis disproportionately affect the Latinx population, with a higher burden in terms of prevalence and severity compared with the non‐Latinx White population [3].

Modest weight losses of 5% to 10% are associated with improvements in many of these comorbidities, including CVD risk factors, T2D, and NAFLD [14, 15, 16, 17]. However, greater weight loss is associated with greater benefits. For example, in the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) study of people with T2D, a ≥10% weight loss was associated with a 21% lower risk of CVD compared with those with stable weight or weight gain [18]. Greater weight loss is therefore an essential long‐term goal in the management of obesity‐related comorbidities.

Challenges in managing obesity in Latinx people

Several challenges exist in obesity management. Hormonal responses to eating are altered in people with obesity compared with people of a healthy weight [8, 9]; these alterations can increase food intake, reduce energy expenditure, and limit weight loss. These homeostatic responses can amplify following weight loss, often contributing to recurrence of overweight [10].

Long‐term weight management is also challenging in part because of an increasingly obesogenic environment. Owing to the high prevalence of comorbidities in people with obesity, many receive drug treatment for additional conditions. However, many of these medications may cause weight gain, although data on medication‐induced weight gain are limited [19]. Medications that can result in weight gain include antidiabetic agents, antidepressants, and glucocorticoids [19]. Several factors specific to Latinx people add to the challenges in managing obesity in this population. Differences in these factors contribute to the heterogeneity of this population (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Overview of the challenges in obesity management in Latinx populations due to heterogeneity

| Challenge in obesity management in the Latinx population | Manifestation in different Latinx subpopulations |

|---|---|

| Internal factors | |

| Genetic susceptibility to obesity and obesity‐related comorbidities |

|

| Environmental factors | |

| Traditional Latinx diets tend to be high in carbohydrates [6], which can promote obesity | |

| Acculturation and/or length of residency is associated with worse diet quality and increased risk of obesity and related comorbidities [26, 68] |

|

| Socioeconomic status influences the risk of obesity [29] |

|

| Gut microbiome factors associated with obesity | |

| Cultural factors | |

| The fuller figure preferred in some Latinx communities may normalize obesity [31] |

|

| Family dynamics can influence a patient's medical decisions, including in the management of obesity [33] |

|

| Health care provider factors | |

| Language barriers can negatively impact on outcomes in obesity management [36] |

|

| Bariatric surgery is underutilized among Latinx people [38], in part because of lack of insurance |

|

Internal factors

Internal factors specific to the Latinx population, such as genetic and epigenetic factors, are associated with obesity and obesity‐related comorbidities, particularly when exposed to an obesogenic environment.

Single‐nucleotide polymorphisms have been identified that are associated with obesity, fat distribution, waist circumference, triglyceride levels, and insulin resistance in Mexican American people [20, 21]. A genome‐wide association study in European and Mexican participants identified three Mexican‐specific single‐nucleotide polymorphisms that were associated with high triglyceride levels [21]. These included the SIK family kinase 3 (SIK3) risk variant rs139961185, which delayed triglyceride clearance after fatty meals [21]. However, environmental factors appear to influence the development of obesity despite similar genetic predisposition within ethnic heritage groups, as illustrated by the higher BMI of Pima Indian people in Arizona (a more affluent environment) compared with those in a remote location in Mexico (living a more traditional lifestyle) [22].

Environmental factors

Environmental factors, such as diet and exercise, also provide challenges in obesity management. A traditional Latinx diet tends to be high in carbohydrates, representing approximately 50% of energy intake across Latinx backgrounds [6]. Diet quality (based on the Healthy Eating Index) varies by background, with better overall dietary quality among people with Mexican, Dominican, and Central American heritage, compared with other Latinx groups [23]. As lower diet quality is associated with obesity, this highlights the need for nutritional interventions to manage obesity in Latinx people.

Access to healthy foods is key in weight management among Latinx people. Food insecurity is associated with obesity in Latina women [24]. In an urban sample, a majority of Latina women reported regularly not having enough money to buy food, and half had been told to change their diet but could not afford to do so [25].

Acculturation of Latinx people to US behaviors and practices is associated with worse diet quality [26]. Similarly, length of residency in the United States predicts moderate and extreme obesity among Latinx people, suggesting that prolonged exposure to the environment in Latinx communities in the United States is a major risk factor for obesity [27]. Among Mexican American people, the association between obesity and length of residency in the United States is mediated primarily by sedentary behavior, suggesting that physical activity interventions may limit the development of obesity [28].

Individual socioeconomic status also predicts obesity and related comorbidities. Among Latinx people, greater household income is associated with lower obesity rates, and higher educational attainment is associated with lower risk of obesity and greater chance of weight loss success [29, 30]. However, the direction and magnitude of the association between socioeconomic status and obesity vary between Latinx groups [29].

Cultural factors

Cultural factors are key contributors to the complexity of obesity management in Latinx people. For example, there are cultural disparities in body ideal, with a larger, curvy body considered acceptable, or even desirable, in many Latinx communities, in contrast with the slender body ideal of the United States [31]. This may contribute to Latinx people who have overweight or obesity being less likely to perceive themselves as having overweight than non‐Latinx White people [32].

Family dynamics play a role in obesity management in Latinx people. In Latinx communities, the extended family is typically considered more important than the individual, and people often seek advice, including on health care matters, from a large number of family members (reviewed by Caballero et al. [33]). In Latinx families, mothers and grandmothers are typically the primary caretakers of many family matters, including health care (reviewed by Caballero et al. [33]). Parental influence impacts obesity management in children, with parenting style, feeding practices, and modeling of healthy behaviors all influencing a child's eating behavior and BMI [34]. When managing obesity among Latinx people, it is therefore critical to understand the family dynamics and to include key family members in discussions and decisions on treatment.

Health care provider factors

Health care provider–related factors can affect obesity management in Latinx communities. There are insufficient health care providers with a Latinx background, with only 4.4% of US physicians in 2013 identifying as Hispanic or Latinx [35]. The shortage of Latinx health care providers can lead to language barriers between Latinx people and their health care providers, which can negatively impact the management of obesity and related comorbidities [36]. Limited English proficiency among Latinx patients is associated with lower receipt of advice about diet and exercise [36].

Access to health care is limited owing to the high rate of uninsured people in the US Latinx population, with 16.1% uninsured in 2017 compared with 6.3% of non‐Latinx White people [37]. This contributes to the lower utilization of bariatric surgery by Latinx people compared with non‐Latinx White people with obesity [38] and likely also to the lower use of antiobesity medications (AOMs) in this population [39]. Lack of health insurance coverage may lead to increased medication‐induced weight gain, as some older, less expensive medications (particularly medications for T2D), may be more obesogenic than newer, more expensive options [19].

Ethnic disparities are also evident in existing clinical criteria, which tend to be developed for broader populations and which may not be appropriate for Latinx populations. For example, the waist circumference threshold to define abdominal obesity as a risk factor for coronary heart disease does not appear to be appropriate for Latina women. The waist circumference cutoff point for optimal discrimination appears higher for Latina women compared with the general population, leading to an overestimate of the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in this group [40].

Strategies for managing obesity in Latinx people: Recommendations for action

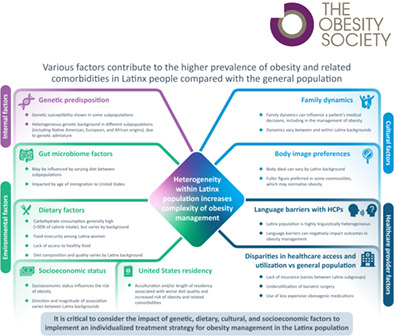

Obesity management typically involves a combination of several strategies, including dietary, lifestyle, pharmacologic, and/or surgical interventions. A patient case illustrating some of these strategies is included in Figure 1. Strategies for the management of obesity tend to be most effective when personalized to the individual. The development of culturally sensitive strategies is therefore key to long‐term successful management of obesity as a chronic disease in the Latinx population.

FIGURE 1.

Case study on the management of obesity and obesity‐related comorbidities in a Latinx patient. AOM, antiobesity medication; CVD, cardiovascular disease; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; VLCD, very low‐calorie diet

Dietary and lifestyle interventions

Interventions that create new models of a healthy diet and lifestyle among matriarchs and patriarchs are key to obesity management in the Latinx population.

Dietary interventions

Promotion of a healthy diet can support the prevention and control of obesity in the Latinx population. Nutrition education programs targeted toward the Latinx community can change dietary behaviors and lead to weight loss [41]. Low‐income Latinx families who received tailored nutrition education from a bicultural dietitian were more likely to adopt healthier food purchasing habits. This challenges the perception that dietary interventions are not feasible in lower‐income families, owing to the higher cost of healthier foods.

Intervening early may be particularly beneficial, as younger age appears to be a risk factor for consuming a diet rich in sugar and fat among Latina women [42].

Lifestyle interventions

Culturally tailored lifestyle intervention programs have shown benefits in obesity management in the Latinx population [43, 44]. A randomized controlled trial assessed the effectiveness of the “Vida Sana/Healthy Life” program, a culturally adapted lifestyle intervention for Latinx families that involved 1 year of in‐person intervention sessions, alongside the use of an activity tracker and a diet‐ and exercise‐tracking app [43]. The intervention was significantly superior to usual care in terms of weight loss and reduction in BMI at 12 months but not at 24 months, suggesting a need for continued support following program completion.

Lifestyle intervention programs can also have a positive impact on obesity‐related comorbidities. The 12‐week Compañeros en Salud program involved educational sessions and home visits by a promotora (facilitator) from the community [44]. The program led to weight loss in the majority of participants, accompanied by improvements in metabolic parameters, including reductions in blood pressure, total cholesterol, glucose, and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) [44]. However, response to a lifestyle intervention in Latinx youth with obesity was found to vary between participants [45]. This could be in part due to the heterogeneity of the Latinx population, suggesting a need for more personalized interventions.

Lastly, interventions that include a physical activity component may be particularly beneficial in attenuating genetic risk [46] or preventing loss of muscle mass that is associated with the development of T2D [47].

Medical and surgical interventions

AOMs can be beneficial in obesity management in Latinx people. Among Mexican American women with obesity, 1 year of orlistat treatment in addition to a culturally tailored lifestyle intervention was associated with weight loss and reductions in waist circumference, total cholesterol, and low‐density lipoprotein compared with waitlist controls [48].

In post hoc analyses of phase 3 studies, weight loss with liraglutide and semaglutide was similar between Latinx and non‐Latinx populations [49, 50, 51]. However, withdrawal rates were numerically higher among Latinx versus non‐Latinx participants [49]. The response to lifestyle intervention in the placebo group was also numerically lower among Latinx participants [49], emphasizing the need for culturally targeted interventions.

In phase 3 trials evaluating the efficacy of semaglutide or phentermine‐containing AOMs, the proportion of Latinx participants was low (12%–20%) [52, 53, 54, 55], highlighting a need for more data in the Latinx population. As with the general population [56] and veteran population [57], determining obesity phenotypes within the Latinx population may help to enhance weight loss and minimize variability in AOM response.

Bariatric surgery can also be beneficial for Latinx people with obesity. Following bariatric surgery, weight loss and BMI reduction were similar between Latinx people and non‐Latinx White people [58, 59], and no differences in terms of mortality, morbidity, hospital length of stay, or costs were observed [60]. However, it has been found that metabolic syndrome is less likely to resolve following bariatric surgery in Latinx adults than non‐Latinx White adults [61]. Although the reasons for this are unknown, it is possible that more severe cardiometabolic disease in Latinx people may lead to impaired metabolic processes that are less responsive to weight loss following surgery [61].

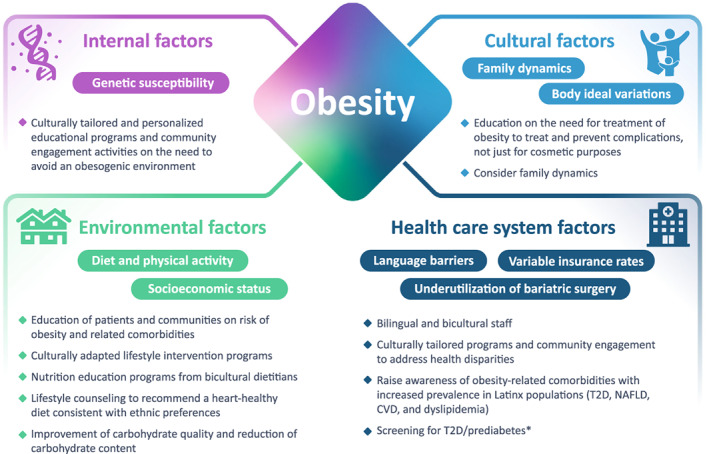

Implementation of personalized, culturally sensitive intervention strategies

Intervention strategies are likely to be most successful when personalized to the individual, with cultural factors a key consideration for Latinx‐targeted interventions.

Ideally, interventions should include bilingual and bicultural staff members who are familiar with the participant's cultural background [62]. Dietary interventions should be adjusted to suit a Latinx diet and more specifically, the diet of the participant's regional background [62].

Understanding family dynamics and including key family members is critical to successful intervention. As matriarchs are typically the primary caretakers in Latinx families (reviewed in Caballero et al. [33]), their participation may be particularly important. However, among Mexican American women, these same familial values can negatively impact weight loss and adherence to interventions [63]. It is important that these cultural aspects are discussed with the individual and not assumed [62], in order to target the intervention to the individual.

The heterogeneity of the Latinx population should also be acknowledged when developing and implementing intervention strategies, as this can impact factors including health care utilization, food choices, and language preference [62] (Table 1). It is also important to understand the acculturation process and consider an individual's level of acculturation, as dietary patterns and food choices typically change on immigration to the United States [64]. However, few studies distinguish between Latin backgrounds, except for Mexican American, as the largest Latinx group in the United States.

When managing obesity, health care providers must be clear when explaining to patients that the concern with obesity is not about being “large” or “fat” but that it involves having excess dysfunctional adipose tissue, which results in disease with comorbidities and complications. Similarly, the aim of treatment is not simply “being thinner,” which may not be desired within the Latinx community, but to prevent and treat obesity‐related diseases. Health care providers should emphasize the importance of screening for obesity‐related conditions, such as T2D, as the prevalence of undiagnosed comorbidities can be high among Latinx people [65].

Programs directed at Latinx patients with T2D have been successful and provide lessons for reaching underserved minority groups in the management of obesity [66]. Factors that were associated with improved outcomes in this population included cultural relevance, longer intervention period, tailoring for low literacy, multimodal implementation (e.g., a combination of in‐person and telephone delivery), and social and familial elements [66].

SUMMARY

In the United States, obesity disproportionately affects the Latinx population, with a higher prevalence of obesity and related comorbidities. The increased burden occurs because of a complex interplay of numerous genetic, dietary, cultural, and socioeconomic factors, with disparities in health care access and low numbers of health care providers from a Latinx background adding to the challenges of managing obesity in the Latinx population. These factors are summarized in Figure 2, alongside recommendations on how to optimize obesity management in Latinx populations. Culturally adapted lifestyle intervention programs and nutritional counseling are essential, in addition to educational programs and community engagement, to increase awareness of the health implications of obesity. Access to bilingual and bicultural health care staff and appropriate screening for comorbidities that have increased prevalence in Latinx populations, such as T2D, can help to reduce health disparities. Latinx groups need individualized care, as they are highly heterogeneous in terms of genetics, diet, language, and culture. When managing obesity, it is critical to consider the many factors that contribute to the increased burden in Latinx people, in order to implement a culturally congruent, personalized strategy to improve outcomes.

FIGURE 2.

Factors for consideration and practical recommendations for action in the management of obesity in Latinx populations. *Testing is recommended in asymptomatic adults with overweight or obesity and one or more risk factors, which include Latinx ethnicity [72]. CVD, cardiovascular disease; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; T2D, type 2 diabetes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to manuscript writing (assisted by a medical writer paid for by the funder) and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

José Orlando Alemán serves on the advisory board for Intellihealth, is a consultant for Novo Nordisk, and receives research support from the NYU Langone Health Comprehensive Program in Obesity Research. Jaime P. Almandoz serves on advisory boards for Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. Juan Pablo Frias reports receiving research support from AbbVie, Akero, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Intercept, Janssen, Madrigal, Metacrine, MSD, NorthSea Therapeutics, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Oramed, Pfizer, Poxil, Sanofi, and Theracos; serving on advisory boards and consulting for 89bio, Akero, Altimmune, Axcella Health, Boehringer Ingelheim, Carmot Therapeutics, Echosens, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Intercept, Merck, Metacrine, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Sanofi; and participating in speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly, Merck, and Sanofi. Rodolfo J. Galindo has received research support (to Emory University) for investigator‐initiated studies from Dexcom, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk, and consulting fees from Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Weight Watchers, outside of this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Rebecca Bridgewater‐Gill of Axis, a division of Spirit Medical Communications Group Limited, under the direction of the authors. Novo Nordisk Inc. performed a medical accuracy review.

Alemán JO, Almandoz JP, Frias JP, Galindo RJ. Obesity among Latinx people in the United States: A review. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023;31(2):329‐337. doi: 10.1002/oby.23638

Funding information Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, New Jersey, USA

REFERENCES

- 1. Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Afful J. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and severe obesity among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 1960–1962 through 2017–2018. National Center for Health Statistics Health E‐Stats; 2020.

- 2. Zhang H, Rodriguez‐Monguio R. Racial disparities in the risk of developing obesity‐related diseases: a cross‐sectional study. Ethn Dis. 2012;22:308‐316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rich NE, Oji S, Mufti AR, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease prevalence, severity, and outcomes in the United States: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:198‐210.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhu Y, Sidell MA, Arterburn D, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes by BMI: Patient Outcomes Research To Advance Learning (PORTAL) multisite cohort of adults in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:2211‐2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Conomos MP, Laurie CA, Stilp AM, et al. Genetic diversity and association studies in US Hispanic/Latino populations: applications in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:165‐184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Siega‐Riz AM, Sotres‐Alvarez D, Ayala GX, et al. Food‐group and nutrient‐density intakes by Hispanic and Latino backgrounds in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:1487‐1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mechanick JI, Hurley DL, Garvey WT. Adiposity‐based chronic disease as a new diagnostic term: the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology position statement. Endocr Pract. 2017;23:372‐378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carroll JF, Kaiser KA, Franks SF, Deere C, Caffrey JL. Influence of BMI and gender on postprandial hormone responses. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:2974‐2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. le Roux CW, Batterham RL, Aylwin SJ, et al. Attenuated peptide YY release in obese subjects is associated with reduced satiety. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, et al. Long‐term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1597‐1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hall KD, Guo J. Obesity energetics: body weight regulation and the effects of diet composition. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1718‐1727.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Masterson Creber RM, Fleck E, Liu J, Rothenberg G, Ryan B, Bakken S. Identifying the complexity of multiple risk factors for obesity among urban Latinas. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19:275‐284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hanis CL, Redline S, Cade BE, et al. Beyond type 2 diabetes, obesity and hypertension: an axis including sleep apnea, left ventricular hypertrophy, endothelial dysfunction, and aortic stiffness among Mexican Americans in Starr County, Texas. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:86. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0405-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481‐1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koutoukidis DA, Koshiaris C, Henry JA, et al. The effect of the magnitude of weight loss on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Metabolism. 2021;115:154455. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Winslow DH, Bowden CH, DiDonato KP, McCullough PA. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study of an oral, extended‐release formulation of phentermine/topiramate for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in obese adults. Sleep. 2012;35:1529‐1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, et al. Recommendations from the international evidence‐based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1602‐1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Look AHEAD Research Group ; Gregg EW, Jakicic JM, Blackburn G, et al. Association of the magnitude of weight loss and changes in physical fitness with long‐term cardiovascular disease outcomes in overweight or obese people with type 2 diabetes: a post‐hoc analysis of the Look AHEAD randomised clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:913‐921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. May M, Schindler C, Engeli S. Modern pharmacological treatment of obese patients. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2020;11:2042018819897527. doi: 10.1177/2042018819897527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boeta‐Lopez K, Duran J, Elizondo D, et al. Association of interleukin‐6 polymorphisms with obesity or metabolic traits in young Mexican‐Americans. Obes Sci Pract. 2017;4:85‐96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ko A, Cantor RM, Weissglas‐Volkov D, et al. Amerindian‐specific regions under positive selection harbour new lipid variants in Latinos. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3983. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ravussin E, Valencia ME, Esparza J, Bennett PH, Schulz LO. Effects of a traditional lifestyle on obesity in Pima Indians. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1067‐1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Siega‐Riz AM, Pace ND, Butera NM, et al. How well do U.S. Hispanics adhere to the dietary guidelines for Americans? Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Health Equity. 2019;3:319‐327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. López‐Cepero A, Frisard C, Lemon SC, Rosal MC. Emotional eating mediates the relationship between food insecurity and obesity in Latina women. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2020;52:995‐1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suplee PD, Jerome‐D'Emilia B, Burrell S. Exploring the challenges of healthy eating in an urban community of Hispanic women. Hisp Health Care Int. 2015;13:161‐170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yoshida YX, Simonsen N, Chen L, Zhang LU, Scribner R, Tseng TS. Sociodemographic factors, acculturation, and nutrition management among Hispanic American adults with self‐reported diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27:1592‐1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Isasi CR, Ayala GX, Sotres‐Alvarez D, et al. Is acculturation related to obesity in Hispanic/Latino adults? Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. J Obes. 2015;2015:186276. doi: 10.1155/2015/186276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murillo R, Albrecht SS, Daviglus ML, Kershaw KN. The role of physical activity and sedentary behaviors in explaining the association between acculturation and obesity among Mexican‐American adults. Am J Health Promot. 2015;30:50‐57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. López‐Cevallos DF, Gonzalez P, Bethel JW, et al. Is there a link between wealth and cardiovascular disease risk factors among Hispanic/Latinos? Results from the HCHS/SOL sociocultural ancillary study. Ethn Health. 2018;23:902‐913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guendelman S, Ritterman Weintraub M, Kaufer‐Horwitz M. Weight loss success among overweight and obese women of Mexican‐origin living in Mexico and the United States: a comparison of two national surveys. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19:41‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Franko DL, Coen EJ, Roehrig JP, et al. Considering J.Lo and Ugly Betty: a qualitative examination of risk factors and prevention targets for body dissatisfaction, eating disorders, and obesity in young Latina women. Body Image. 2012;9:381‐387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pourat N, Chen X, Lu C, et al. Racial/ethnic variations in weight management among patients with overweight and obesity status who are served by health centres. Clin Obes. 2020;10:e12372. doi: 10.1111/cob.12372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Caballero AE. Understanding the Hispanic/Latino patient. Am J Med. 2011;124(10 suppl):S10‐S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ochoa A, Berge JM. Home environmental influences on childhood obesity in the Latino population: a decade review of literature. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19:430‐447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Association of American Medical Colleges . Current status of the U.S. physician workforce. Diversity in the Physician Workforce: Facts & Figures 2014. Accessed May 26, 2021. http://www.aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org/section-ii-current-status-of-us-physician-workforce/

- 36. Lopez‐Quintero C, Berry EM, Neumark Y. Limited English proficiency is a barrier to receipt of advice about physical activity and diet among Hispanics with chronic diseases in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(suppl 5):S62‐S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Berchick ER, Hood E, Barnett JC. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2017. Current Population Reports, P60‐264, Issued September 2018. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-264.pdf

- 38. Messiah SE, Xie L, Atem F, et al. Disparity between United States adolescent class II and III obesity trends and bariatric surgery utilization, 2015–2018. Ann Surg. 2022;276:324‐333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Elangovan A, Shah R, Smith ZL. Pharmacotherapy for obesity‐trends using a population level national database. Obes Surg. 2021;31:1105‐1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chirinos DA, Llabre MM, Goldberg R, et al. Defining abdominal obesity as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in the U.S.: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Diabetes Care. 2020;43:1774‐1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cortés DE, Millán‐Ferro A, Schneider K, Vega RR, Caballero AE. Food purchasing selection among low‐income Spanish‐speaking Latinos. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(3 suppl 3):S267‐S273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Arias‐Gastélum M, Lindberg NM, Leo MC, et al. Dietary patterns with healthy and unhealthy traits among overweight/obese Hispanic women with or at high risk for type 2 diabetes. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8:293‐303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rosas LG, Lv N, Xiao L, et al. Effect of a culturally adapted behavioral intervention for Latino adults on weight loss over 2 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2027744. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schwartz R, Powell L, Keifer M. Family‐based risk reduction of obesity and metabolic syndrome: an overview and outcomes of the Idaho Partnership for Hispanic Health. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(2 suppl):129‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Peña A, McNeish D, Ayers SL, et al. Response heterogeneity to lifestyle intervention among Latino adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2020;21:1430‐1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moon JY, Wang T, Sofer T, et al. Objectively measured physical activity, sedentary behavior, and genetic predisposition to obesity in U.S. Hispanics/Latinos: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Diabetes. 2017;66:3001‐3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. LeCroy MN, Hua S, Kaplan RC, et al. Associations of changes in fat free mass with risk for type 2 diabetes: Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;171:108557. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Poston WS, Reeves RS, Haddock CK, et al. Weight loss in obese Mexican Americans treated for 1‐year with orlistat and lifestyle modification. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:1486‐1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. O'Neil PM, Garvey WT, Gonzalez‐Campoy JM, et al. Effects of liraglutide 3.0 mg on weight and risk factors in Hispanic versus non‐Hispanic populations: subgroup analysis from scale randomized trials. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:1277‐1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Davidson JA, Ørsted DD, Campos C. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide, a once‐daily human glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogue, in Latino/Hispanic patients with type 2 diabetes: post hoc analysis of data from four phase III trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:725‐728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. DeSouza C, Cariou B, Garg S, et al. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide for type 2 diabetes by race and ethnicity: a post hoc analysis of the SUSTAIN trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:543‐556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once‐weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:989‐1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Davies M, Færch L, Jeppesen OK, et al. Semaglutide 2·4 mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2): a randomised, double‐blind, double‐dummy, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:971‐984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wadden TA, Bailey TS, Billings LK, et al. Effect of subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo as an adjunct to intensive behavioral therapy on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:1403‐1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Look M, et al. Two‐year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled‐release phentermine/topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): a randomized, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 extension study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:297‐308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Acosta A, Camilleri M, Abu Dayyeh B, et al. Selection of antiobesity medications based on phenotypes enhances weight loss: a pragmatic trial in an obesity clinic. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29:662‐671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pendse J, Valljo‐García F, Parziale A, et al. Obesity pharmacotherapy is effective in the Veterans Affairs patient population: a local and virtual cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29:308‐316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Khorgami Z, Arheart KL, Zhang C, Messiah SE, de la Cruz‐Muñoz N. Effect of ethnicity on weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2015;25:769‐776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhao J, Samaan JS, Abboud Y, Samakar K. Racial disparities in bariatric surgery postoperative weight loss and co‐morbidity resolution: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17:1799‐1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kröner Florit PT, Corral Hurtado JE, Wijarnpreecha K, Elli EF, Lukens FJ. Bariatric surgery, clinical outcomes, and healthcare burden in Hispanics in the USA. Obes Surg. 2019;29:3646‐3652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Coleman KJ, Huang YC, Koebnick C, et al. Metabolic syndrome is less likely to resolve in Hispanics and non‐Hispanic blacks after bariatric surgery. Ann Surg. 2014;259:279‐285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lindberg NM, Stevens VJ, Halperin RO. Weight‐loss interventions for Hispanic populations: the role of culture. J Obes. 2013;2013:542736. doi: 10.1155/2013/542736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Austin JL, Smith JE, Gianini L, Campos‐Melady M. Attitudinal familism predicts weight management adherence in Mexican‐American women. J Behav Med. 2013;36:259‐269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gray VB, Cossman JS, Dodson WL, Byrd SH. Dietary acculturation of Hispanic immigrants in Mississippi. Salud Publica Mex. 2005;47:351‐360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lindberg NM, Vega‐López S, LeBlanc ES, et al. High prevalence of undiagnosed hyperglycemia in low‐income overweight and obese Hispanic women in Oregon. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6:799‐805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fortmann AL, Savin KL, Clark TL, Philis‐Tsimikas A, Gallo LC. Innovative diabetes interventions in the U.S. Hispanic population. Diabetes Spectr. 2019;32:295‐301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Norris ET, Wang L, Conley AB, et al. Genetic ancestry, admixture and health determinants in Latin America. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(suppl 8):861. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5195-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Commodore‐Mensah Y, Ukonu N, Obisesan O, et al. Length of residence in the United States is associated with a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in immigrants: a contemporary analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e004059. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kaplan RC, Wang Z, Usyk M, et al. Gut microbiome composition in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos is shaped by geographic relocation, environmental factors, and obesity. Genome Biol. 2019;20:219. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1831-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. George VA, Erb AF, Harris CL, Casazza K. Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders in Hispanic females of diverse ethnic background and non‐Hispanic females. Eat Behav. 2007;8:1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health . Minority population profiles: Hispanic/Latino Americans. Updated September 26, 2022. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=64#:~:text=Among%20Hispanic%20subgroups%2C%20coverage%20varied,percent%20for%20non%2DHispanic%20whites

- 72. American Diabetes Association . 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Ddiabetes‐2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S15‐S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]