PURPOSE:

Since 2016, the American College of Surgeons' Commission on Cancer (CoC) has required routine distress screening (DS) of cancer survivors treated in their accredited facilities to facilitate early identification of survivors with psychosocial concerns. Lung and ovarian cancer survivors have relatively low 5-year survival rates and may experience high levels of distress. We examined the extent to which ovarian and lung cancer survivors received CoC-mandated DS and whether DS disparities exist on the basis of diagnosis, sociodemographic factors, or facility geography (urban/rural).

METHODS:

This study included a quantitative review of DS documentation and follow-up services provided using existing electronic health records (EHRs). We worked with 21 CoC-accredited facilities across the United States and examined EHRs of 2,258 survivors from these facilities (1,618 lung cancer survivors and 640 ovarian cancer survivors) diagnosed in 2016 or 2017.

RESULTS:

Documentation of DS was found in half (54.8%) of the EHRs reviewed. Disparities existed across race/ethnicity, cancer type and stage, and facility characteristics. Hispanic/Latino and Asian/Pacific Islander survivors were screened at lower percentages than other survivors. Patients with ovarian cancer, those diagnosed at earlier stages, and survivors in urban facilities had relatively low percentages of DS. Non-Hispanic Black survivors were more likely than non-Hispanic White survivors to decline further psychosocial services.

CONCLUSION:

Despite the mandate for routine DS in CoC-accredited oncology programs, gaps remain in how many and which survivors are screened for distress. Improvements in DS processes to enhance access to DS and appropriate psychosocial care could benefit cancer survivors. Collaboration with CoC during this study led to improvement of their processes for collecting DS data for measuring standard adherence.

INTRODUCTION

Studies have shown that 33%-50% of cancer survivors (ie, a person who has ever been diagnosed with cancer)1 experience psychosocial distress at some point during their cancer treatment journey2-7; differences in prevalence of distress vary by cancer type3,4 and prognosis.2,8,9 Distress in cancer survivors is defined as an unpleasant psychological, social, emotional, and/or spiritual experience that interferes with the ability to effectively cope with a cancer diagnosis, symptoms, or subsequent treatment side effects.10

Since 2016, the American College of Surgeons' Commission on Cancer (CoC) has required accredited programs to screen patients with cancer for distress at least once during their initial course of treatment and to document distress screening (DS) and follow-up to a positive screen.11,12 DS provides an opportunity to identify survivors with psychosocial concerns who may be reluctant to discuss them with providers unless asked.13,14 Addressing distress with timely psychosocial interventions reduces distress experienced by survivors, which can improve cancer-related outcomes and reduce strain on the medical system.15-17 Screening for and managing distress in cancer survivors is an essential component of quality care,18-20 and meeting psychosocial needs has been associated with longer survival.21,22

Survival from lung and ovarian cancer is relatively low (5-year survival: 23% and 49%, respectively); lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death among all Americans, and ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death among American women.23 Lung cancer survivors experience high levels of distress.24-28 In 2016, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine called for increased study and attention on psychosocial needs of ovarian cancer survivors,29 recognizing both high rates of depression, anxiety, and distress and under-representativeness in psychosocial research (including DS).30

Studies of DS implementation in oncology settings have identified gaps and highlighted different factors to be considered in some survivor populations31,32 and have documented racial disparities in screening for33,34 and treating distress.31,35 Successful implementation of routine DS in oncology settings requires thoughtful planning, appropriate use of a scientifically valid and culturally responsive tool, and appropriate follow-up.18,32,36,37 Psychosocial distress among older (ie, over 60 years old) cancer survivors who are Black and Hispanic is relatively unknown, because of their under-representation in the literature.38

Given the under-representation of both lung and ovarian cancer survivors in the existing psychosocial literature, this study focused on the extent to which these survivors received CoC-mandated DS and whether racial, ethnic, or other disparities existed in screening percentages or patterns of DS-related care. To our knowledge, this is the first study focused entirely on disparities experienced by lung and ovarian cancer survivors related to DS and management.

METHODS

We designed a mixed-method study that included a quantitative review of existing electronic health records (EHRs) to assess DS and management and qualitative interviews and focus groups with health care practitioners about challenges and facilitators of conducting DS and management. This article reports on the analysis of EHR data. A detailed description of the methods has been published previously.39 Briefly, we enrolled 21 CoC-accredited health care facilities between August 2018 and May 2020 to participate in the study. Facility location and urbanicity were as follows: Midwest (4), Northeast (5), South (7), and West (5); urban (16); and rural (5). As incentive for study participation, facilities were offered credit toward CoC's Standard 4.7 Study of Quality (2016 Edition)12 or credit for the number of survivors as accrued for Standard 9.1 Clinical Research Accrual Study (2020 Edition).41 On study completion, each facility received tailored feedback reports of their findings compared with findings aggregated across all study facilities to be used for identifying gaps in DS and management and opportunities for quality improvement. The investigation was performed after approval by the Centers for Disease Control Human Subjects Review Board (Protocol #7225.0), Westat's Institutional Review Board (Protocol #6282.07), and a local Human Investigations Committee, in accordance with an assurance filed with and approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Informed consent was not needed since this analysis used data already collected in EHRs.

Data Collection

On the basis of results from a power analysis, up to 130 cases were statistically sampled from each facility to collect a minimum of 2,000 patients across facilities. Once the final sample was drawn, we reviewed EHRs for information about DS and related follow-up, using categories (eg, emotional support, financial support, and community services) adapted from the Oncology Social Work intervention index (OSWii),42 an instrument for categorizing psychosocial care. Ten facilities initially recruited were excluded because of ineligibility (eg, low case counts, no DS protocol, or data unavailable for the period of interest).

Demographic and Cancer Characteristics

We compared the following demographic characteristics overall and between lung and ovarian cancer survivor groups: sex (male or female), age (18-44, 45-64, and 65+ years), race/ethnicity (White, non-Hispanic; Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; Asian/Pacific Islander; American Indian/Alaska Native; and Others), urbanicity (rural and urban location of the treatment facility), and health insurance (public, private, other/uninsured, and unknown), which served as a proxy for socioeconomic status. Cancer characteristics were abstracted and compared with American Joint Committee on Cancer stage (I-IV), which was based on a combination of clinical and pathologic staging criteria.43

Health Behavior Characteristics

We compared the proportion overall and between lung and ovarian cancer survivor groups who had any previous diagnoses or history of mental health-related conditions (eg, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and suicidal ideation). Smoking status was classified as survivors who never smoked, survivors who used to smoke, and survivors who smoke, on the basis of self-report and previous referrals for smoking cessation. All health behavior characteristics were defined using a combination of relevant International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification codes,44 EHR problem list (ie, patient history, current diagnoses, and problems the patient was being seen for), or other patient documentation (eg, DS screenings and staff notes).

Patterns of DS-Related Care

We examined whether DS was offered and reasons for DS not being offered overall, between lung and ovarian cancer survivor groups, and across facilities. We classified some cancer survivors as not eligible for DS (and excluded them from analyses) because they were seen only once and/or were not treated at the facility, died before screening occurred or transitioned to hospice, or did not reach the pivotal point for DS (eg, received treatment at the facility but were not seen in a department or service where DS was administered). Of those screened for distress, further information was abstracted from EHRs on whether they screened positive for distress (on the basis of a validated threshold for the screening instrument being used), received a psychosocial assessment, and/or were referred for further psychosocial services, as needed. We also examined reasons that survivors reported being distressed.

Data Analysis

Chi-square analyses were completed to test for significant differences between lung and ovarian cancer survivors across demographic, cancer, and health behavior characteristics and between these characteristics and receipt of DS (overall and within each cancer survivor group). The Breslow-Day test of homogeneity45,46 was used to test for significant differences of DS among lung and ovarian cancer survivors across demographic, cancer, and health behavior characteristics. P < .05 were considered statistically significant. Because of small numbers of survivors of races other than non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black, analyses of disparities in DS patterns of care could only be conducted between those two races. All analyses were completed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

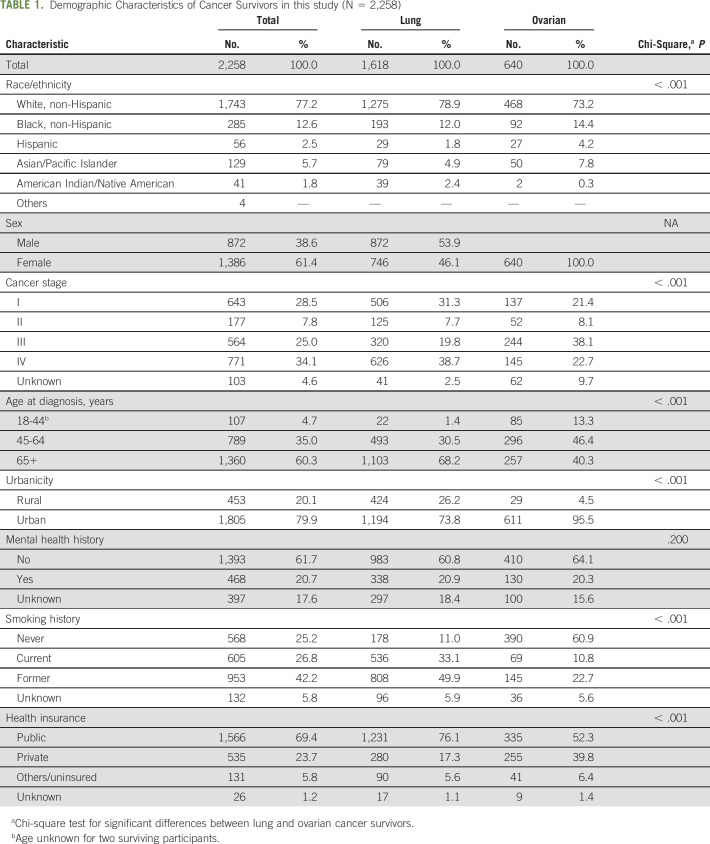

We abstracted data for 2,258 survivors with lung or ovarian cancer across 21 cancer treatment facilities. The primary DS tool used was the Distress Thermometer (61.5%), followed by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 (11.5%), PHQ-4 (7.7%), PHQ-2 (3.8%), and other local instruments (15.4%). Characteristics of participating survivors are summarized in Table 1. Lung and ovarian cancer survivors differed significantly across several demographic characteristics. The majority of survivors were non-Hispanic White (77.2%), age 65 years or older at the time of diagnosis (60.3%), lived in urban areas (79.9%), had no history of mental health conditions (61.7%), and were insured by public (Medicare or Medicaid) insurance (69.4%). Approximately one third (34.1%) of survivors had stage IV disease, and 69% had former (42.2%) or current (26.8%) smoking histories.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Cancer Survivors in this study (N = 2,258)

DS Disparities

Of all eligible participating survivors, 54.8% were screened for distress (Table 2).

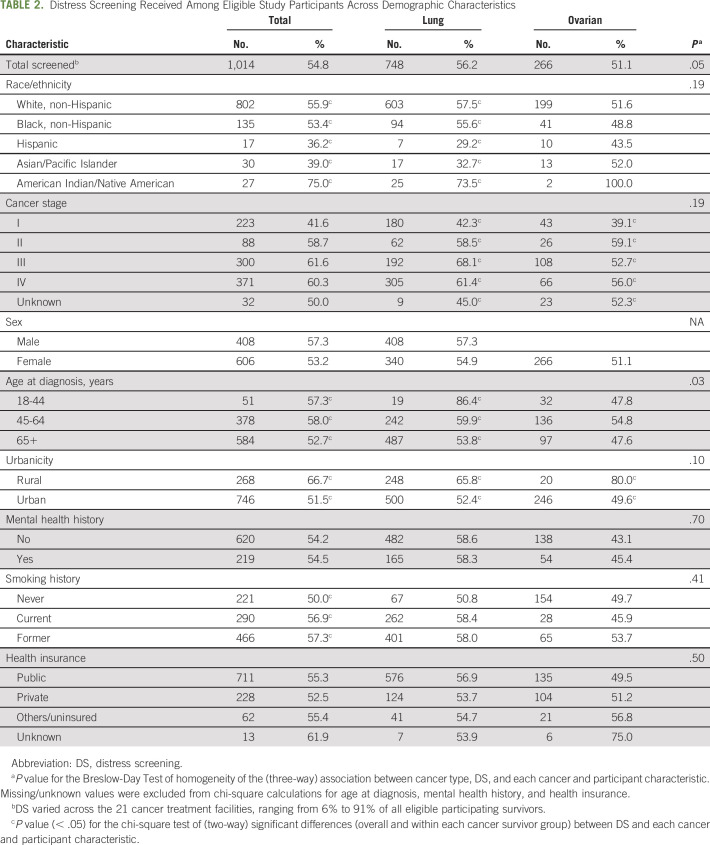

TABLE 2.

Distress Screening Received Among Eligible Study Participants Across Demographic Characteristics

Among all cancer survivors, DS differed significantly by race/ethnicity, cancer stage, urbanicity, and smoking history (P < .05). Screening percentages were highest for American Indian/Alaska Natives (75.0%) and lowest for Hispanic (36.2%) and Asian/Pacific Islander (39.0%) survivors. Screening for survivors in rural areas (66.7%) was significantly higher compared with urban areas (51.5%). Screening for distress was highest among survivors diagnosed with stage III (61.6%) and lowest for stage I (41.6%). Screening percentages for distress among survivors who used to smoke (57.3%) or who smoke (56.9%) were significantly higher than rates for survivors who never smoked (50.0%).

DS was significantly higher among lung cancer survivors (56.2%) than ovarian cancer survivors (51.1%). This association between the cancer site and DS varied significantly by age at diagnosis (P < .03). DS for lung cancer survivors was significantly higher for those who were diagnosed at age 18-44 years (86.4%) compared with those who were diagnosed at age 45-64 years (59.9%) or 65+ years (53.8%). DS for ovarian cancer survivors was significantly higher for those who were diagnosed at age 45-64 years (54.8%) compared with those who were diagnosed at age 18-44 years (47.8%) or 65+ years (47.6%). DS varied widely across the 21 cancer treatment facilities, ranging from 6% to 91% of all eligible participating survivors. The first DS most commonly occurred at the first oncologist visit (point of screening, 35.7%) and in the outpatient medical oncology setting (location screened, 55.1%; results not shown).

DS Reasons and Outcomes

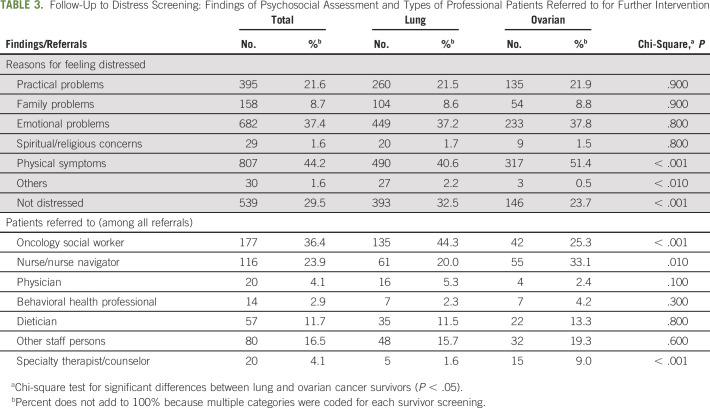

The most common reasons that survivors reported feeling distressed (as noted on the distress screen's problem list) were related to their experience of physical symptoms (44.2%), due to emotional problems (37.4%), and related to practical problems (eg, childcare, housing, insurance/finances, transportation; 21.6%; Table 3). The most common services that survivors were referred to for management of distress were an oncology social worker (36.4%), nurse/nurse navigator (23.9%), other unspecified staff persons (16.5%), or dietician (11.7%).

TABLE 3.

Follow-Up to Distress Screening: Findings of Psychosocial Assessment and Types of Professional Patients Referred to for Further Intervention

The reasons that survivors reported feeling distressed differed significantly between lung and ovarian cancer survivors. Lung cancer survivors were significantly less likely than ovarian survivors to report their reason for feeling distressed as physical symptoms (40.6% v 51.4%, respectively) and significantly more likely to report not being distressed (32.5% v 23.7%, respectively).

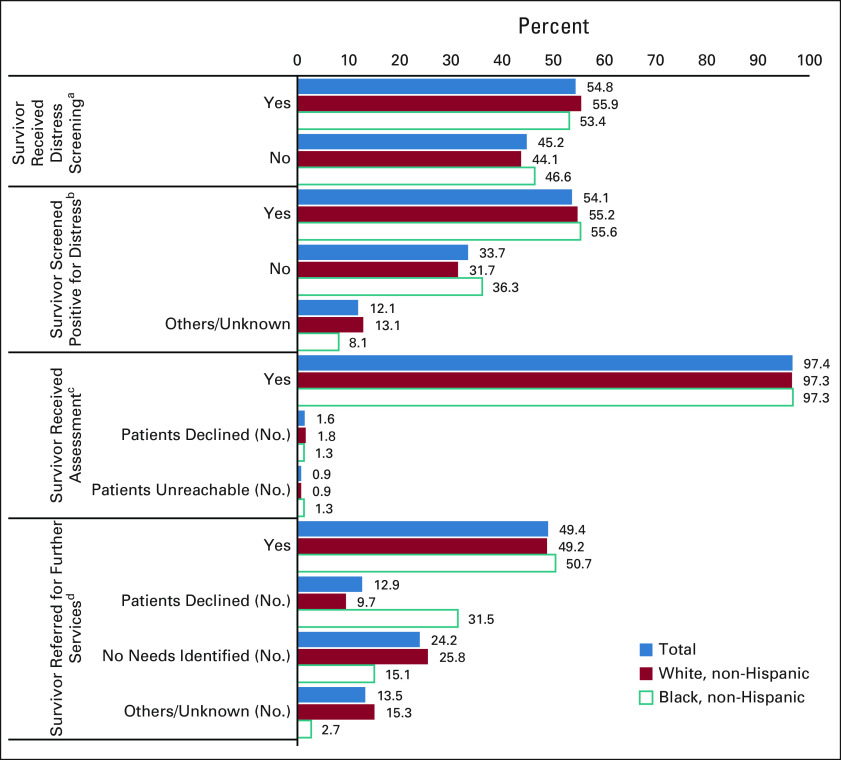

Of survivors screened for distress (n = 1,014, 54.8%), 54.1% (549 of 1,014) screened positive for distress, thereby warranting a psychosocial assessment (Fig 1), but for 12.1% (123 of 1,014) of survivors, the DS score was not documented. Most survivors (97.4%; 535 of 549) screening positive for distress received a psychosocial assessment, but a small percentage declined (1.6%) or were unreachable (0.9%). Of survivors who received a psychosocial assessment, 49.4% were referred for further services, 12.9% declined further services, and follow-up was unknown for 13.5%. A total of 24.2% of survivors had no further needs identified after the psychosocial assessment.

FIG 1.

Patterns of DS-related care among non-Hispanic White (n = 1,743) and non-Hispanic Black (n = 285) cancer survivors (N = 2,258; this analysis could only be conducted with non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black survivor data because of the small numbers of survivors of other races). aFour hundred six study participants were never eligible for DS because they did not reach the pivotal visit for DS, died before there was an opportunity for DS, or were sent to hospice. bOf those who were screened (total [n = 1,014]), 802 were non-Hispanic White survivors and 135 were non-Hispanic Black survivors. cOf those who were screened and screened positive for distress (total [n = 549]), 443 were non-Hispanic White survivors and 75 were non-Hispanic Black survivors. dOf those who were screened, screened positive for distress, and received assessment (total [n = 535]), 431 were non-Hispanic White survivors and 73 were non-Hispanic Black survivors; significant differences were observed between non-Hispanic White and Black survivors (P < .001). DS, distress screening.

Patterns of DS-Related Care Disparities

Receiving DS, screening positive for distress, and receiving an assessment did not differ significantly between non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black survivors although receiving a referral for further services differed significantly (P < .001). Non-Hispanic Black survivors were more likely than non-Hispanic White survivors to decline further services (31.5% v 9.7%, respectively); however, non-Hispanic Black survivors were less likely than non-Hispanic White survivors to have no needs for further services identified (15.1% v 25.8%, respectively).

DISCUSSION

This study identified disparities in the administration and receipt of DS and distress management at both the facility level and the survivor level. DS rates differed greatly depending on the facility where survivors received cancer treatment, and a higher percentage of survivors were screened at rural versus urban facilities. Among cancer survivors, we found disparities throughout the DS and management process, from screening to referral for additional psychosocial services.

The wide variation of DS rates (6%-91%) of lung and ovarian cancer survivors across cancer care facilities was unexpected and indicates that some facility protocols for DS did not include lung and/or ovarian cancer service lines. This can contribute to disparities in DS by cancer diagnosis if survivors are treated in facilities with DS protocols that do not include their diagnosis. At the time of the study, the CoC's main method of determining compliance with the DS standard was based on a facility's reporting of their policies and procedures. If DS protocols were in place and being followed, regardless of whether all cancers were included in the DS protocols, a facility is considered in compliance.47 On the other hand, for facilities to ensure that they are providing the same level of psychosocial care to all cancer survivors, it is important for them to include all service lines in DS and management protocols. Other US studies, not focused on lung and ovarian cancer survivors, found higher rates of DS (62.7%-75.7%),48-50 further supporting our assumption that facility DS protocols may be driving disparities. Institutional capacity, such as availability of psychosocial staff,51 may make such comprehensive protocols difficult to implement. A surprising finding was that cancer survivors treated in rural facilities were screened for distress at higher rates than those treated in urban facilities. Although this finding was unexpected because health and mental health disparities are routinely reported among rural cancer survivors,52-55 it may be an indication of better balance between staff and patients and that progress is being made in addressing disparities in rural cancer survivorship.56

Our study found that disparities in receipt of DS existed across demographic categories, most notably, race/ethnicity, cancer diagnosis, age at diagnosis, and cancer stage. Non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black survivors were screened for distress at similar rates; however, Hispanic/Latino and Asian/Pacific Islander survivors were screened at rates lower than all other survivors. This is concerning given that Latino and Asian/Pacific Islander lung cancer survivors have previously reported a greater number of unmet supportive care needs than their White counterparts57 and a systematic review found quality-of-life outcomes among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors to be worse than any other racial/ethnic group.58 Our findings that lung cancer survivors were screened at higher rates than ovarian cancer survivors could reflect that some CoC-accredited facilities focus screening efforts on the most common cancer diagnoses at their facilities. Our study also found that survivors with more advanced disease got screened at higher rates than those with an earlier disease stage. All survivors, regardless of cancer diagnosis or cancer stage, could benefit from DS and management since they are components of quality cancer care,18-20 and psychosocial support has been associated with longer survival.21

An encouraging finding was that among survivors who screened positive for distress, nearly all (97%) received a psychosocial assessment. This is higher than those documented in other studies.4,48,49,59 Consistent with the previous literature, this study found that the three most common reasons survivors reported feeling distressed were physical symptoms, emotional problems, and practical problems.48,60 Although consistent with other literature,61 our finding that nearly a third of non-Hispanic Black survivors declined psychosocial support is concerning because Black cancer survivors experience higher distress62,63 and have more unmet psychosocial needs than White cancer survivors.58 It is not clear from our data why survivors decline follow-up support, although stigma around mental illness may contribute and has been found to be higher among people from racial and ethnic minority groups than those from majority groups.64 Oncologist recommendations increase survivor uptake of psychosocial support,65 and implicit bias66-69 may contribute to fewer oncologist recommendations of psychosocial support to Black survivors. Relatedly, a study found that the perception of racism in one's health care provider increased the likelihood of delaying or forgoing necessary medical care.69 Our study found that the professionals to whom cancer survivors were most often referred were oncology social workers, a large proportion (91%) of whom are White.70 The lack of racial concordance between psychosocial staff and survivors may also contribute to the higher percentage of Black survivors declining follow-up support, given that studies have shown longstanding mistrust71,72 in the medical system among many in the Black community.73-76

Despite the CoC requirement to maintain DS documentation, our study found that facilities were not always able to document DS results or postassessment referrals. Other studies have also found documentation of DS and management to be lacking.48,49,59 Tools, such as the OSWii, that capture the range and complexity of psychosocial interventions delivered in cancer care may improve documentation of psychosocial support recommended to and received by survivors.42

Study limitations specific to data include that since EHR data were not collected for research purposes, analyses were limited by available data (eg, mental health history was missing in nearly 18% of EHRs reviewed), data collection varied by EHR system and facility, study participants were extremely heterogenous, and DS documentation was not standardized. We developed a data abstraction tool to standardize data from each facility's cancer registry database, including the manual abstraction of nonstandardized data fields. The abstraction tool included the OSWii,42 developed by oncology social work practitioners, to standardize how intervention data after the DS were collected. Second, our study only included a sample of CoC facilities who met the minimum number of lung and ovarian case requirements and who could support study procedures. The findings of DS processes and completion may not be generalizable to all CoC facilities, CoC facilities with smaller numbers of cancer survivors or lesser EHR capabilities, or non-CoC facilities; however, significant ongoing, intentional collaboration between the study investigators and CoC staff and leadership informed development of the study, analyses, reporting, and implementation of findings. Finally, although we captured a large number of cancer survivors overall and oversampled non-White survivors, our sample was not demographically representative of all cancer survivors, and we were limited in the comparisons that could be completed for the various distress-related patterns of care beyond non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black survivors.

In conclusion, DS and management hold promise to improve the quality of life for cancer survivors. Our findings demonstrate that DS is performed variably among lung and ovarian cancer survivors and disparities exist. These results may be used to improve DS processes and enhance access to DS and appropriate psychosocial care for lung and ovarian cancer survivors. Collaborating with CoC enabled them to use these findings to improve processes for collecting DS data for accreditation purposes. This study illustrated that DS protocol reporting may be insufficient for CoC to determine compliance with DS standard and resulted in improvements to the data collection tool in the CoC prereview questionnaire77 that captures how facilities are meeting this standard. Future studies could aim to understand the factors, including implicit bias and structural racism, contributing to refusal of psychosocial services that may help survivors manage their distress. Studies could also explore the intersectionality among race/ethnicity, rural/urban location, and socioeconomic status to further identify disparities in DS and management to ensure that all cancer survivors receive adequate psychosocial care.

APPENDIX 1.

Additional Methods Details

Cases were stratified into four groups by cancer type and race/ethnicity to generate a systematic random sample: (1) ovarian, non-Hispanic White; (2) ovarian, minority (ie, any race/ethnicity other than non-Hispanic White); (3) lung, minority; and (4) lung, non-Hispanic White. Each sample was split evenly between ovarian and lung cancer records where possible; all ovarian records were included from facilities with fewer than 65 ovarian records, and we sampled additional lung cancer records to make up the difference. Within race/ethnicity, minority cases were oversampled for both cancer types at twice the rate of nonminority cases where possible. Within cancer type, cases were sorted by sex (lung cancer only), clinical cancer stage, age at diagnosis, and payment source to ensure a representative sample within those variables of interest. First, facilities provided an extract of standardized data from their cancer registry database, which included demographics data on eligible survivors and cancer data (eg, primary site and stage) that met the following selection criteria: primary site (lung or ovarian), diagnosed in 2016 or 2017, and diagnosed or treated at the participating facility to sample from. Data were abstracted by either study staff through remote access to facility electronic health records or facility staff and securely transferred to study staff to conduct abstraction.38

Additional Discussion Points

Age-related distress screening (DS) disparities varied by diagnosis. Younger (18-44 years) lung cancer survivors were screened for distress more often than older lung cancer survivors (45-64 years), but the opposite was true for ovarian cancer survivors. Older (45-64 years) ovarian cancer survivors had higher rates of DS than younger survivors (18-44 years). Regardless of DS screening rates, studies have found that older cancer survivors, in general, are less likely than younger survivors to be referred for psychosocial services, even when needs were identified (Mayor S: British Medical Journal Publishing Group, 2017).

DISCLAIMER

This is a US Government work. There are no restrictions on its use.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented at American Society of Preventive Oncology 45th annual meeting, March 2021, virtual poster presentation, and American Psychosocial Oncology Society, March 2022, virtual poster presentation (forthcoming).

SUPPORT

Supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Elizabeth A. Rohan, M. Shayne Gallaway, Grace C. Huang, Diane Ng, Jennifer E. Boehm, Karen Stachon

Administrative support: All authors

Provision of study materials or patients: Diane Ng, Karen Stachon

Collection and assembly of data: M. Shayne Gallaway, Diane Ng

Data analysis and interpretation: Elizabeth A. Rohan, M. Shayne Gallaway, Jennifer E. Boehm, Ruvini Samarasinha, Karen Stachon

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disparities in Psychosocial Distress Screening and Management of Lung and Ovarian Cancer Survivors

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control : Cancer Survivors—Cancer Patients: Diagnosis and Treatment. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/survivors/patients/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zabora J, Knight L: The utility of psychosocial screening in primar care settings. Prim Care Cancer 21:50-53, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zabora JR, Macmurray L: The history of psychosocial screening among cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol 30:625-635, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funk R, Cisneros C, Williams RC, et al. : What happens after distress screening? Patterns of supportive care service utilization among oncology patients identified through a systematic screening protocol. Support Care Cancer 24:2861-2868, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson LE, Zelinski EL, Toivonen KI, et al. : Prevalence of psychosocial distress in cancer patients across 55 North American cancer centers. J Psychosoc Oncol 37:5-21, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kendall J, Glaze K, Oakland S, et al. : What do 1281 distress screeners tell us about cancer patients in a community cancer center? Psychooncology 20:594-600, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehnert A, Hartung TJ, Friedrich M, et al. : One in two cancer patients is significantly distressed: Prevalence and indicators of distress. Psychooncology 27:75-82, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krebber AM, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, et al. : Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: A meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psychooncology 23:121-130, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zabora JR, Diaz L, Loscalzo MJ: Psychosocial screening goes mainstream: A prospective problem-solving system as an essential element of comprehensive cancer care: Background and rationale. Psychooncology 12:S71, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Comprehensive Cancer Network : NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Distress Management, Version 2.2018. 2019. https://www.nccn.org/patients/resources/life_with_cancer/distress.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 11.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care (2016 Edition). 2015. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/standards [Google Scholar]

- 12.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer : Optimal Resources for Cancer Care 2020 Standards. 2019. https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/cancer/coc/optimal_resources_for_cancer_care_2020_standards.ashx [Google Scholar]

- 13.Detmar SB, Aaronson NK, Wever LD, et al. : How are you feeling? Who wants to know? Patients' and oncologists' preferences for discussing health-related quality-of-life issues. J Clin Oncol 18:3295-3301, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pirl WF, Muriel A, Hwang V, et al. : Screening for psychosocial distress: A national survey of oncologists. J Support Oncol 5:499-504, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, et al. : Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 31:782-793, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutgendorf SK, Andersen BL: Biobehavioral approaches to cancer progression and survival: Mechanisms and interventions. Am Psychol 70:186-197, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mundle R, Afenya E, Agarwal N: The effectiveness of psychological intervention for depression, anxiety, and distress in prostate cancer: A systematic review of literature. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 24:674-687, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, et al. : Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol 32:1605-1619, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine : Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashing KT, Loscalzo M, Burhansstipanov L, et al. : Attending to distress as part of quality, comprehensive cancer care: Gaps and diversity considerations. Expert Rev Qual Life Cancer Care 1:257-259, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lutgendorf SK, De Geest K, Bender D, et al. : Social influences on clinical outcomes of patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 30:2885-2890, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733-742, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group : U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, Based on 2021 Submission Data (1999-2019). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute, 2022. www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rohan EA, Boehm J, Allen KG, et al. : In their own words: A qualitative study of the psychosocial concerns of posttreatment and long-term lung cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol 34:169-183, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, et al. : Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord 141:343-351, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eichler M, Hechtner M, Wehler B, et al. : Psychological distress in lung cancer survivors at least 1 year after diagnosis—Results of a German multicenter cross-sectional study. Psychooncology 27:2002-2008, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graves KD, Arnold SM, Love CL, et al. : Distress screening in a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic: Prevalence and predictors of clinically significant distress. Lung Cancer 55:215-224, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brintzenhofe-Szoc KM, Levin TT, Li Y, et al. : Mixed anxiety/depression symptoms in a large cancer cohort: Prevalence by cancer type. Psychosomatics 50:383-391, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alvarez RD, Karlan BY, Strauss JF: “Ovarian cancers: Evolving paradigms in research and care”: Report from the Institute of Medicine. Gynecol Oncol 141:413-415, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Fuchs A, et al. : Long-term survival from gynecologic cancer: Psychosocial outcomes, supportive care needs and positive outcomes. Gynecol Oncol 104:381-389, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlson LE, Bultz BD: Benefits of psychosocial oncology care: Improved quality of life and medical cost offset. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:8, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kayser K, Acquati C, Tran TV: No patients left behind: A systematic review of the cultural equivalence of distress screening instruments. J Psychosoc Oncol 30:679-693, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tai-Seale M, Bramson R, Drukker D, et al. : Understanding primary care physicians' propensity to assess elderly patients for depression using interaction and survey data. Med Care 43:1217-1224, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tai-Seale M, McGuire T, Colenda C, et al. : Two-minute mental health care for elderly patients: Inside primary care visits. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:1903-1911, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffman BM, Zevon MA, D'Arrigo MC, et al. : Screening for distress in cancer patients: The NCCN rapid-screening measure. Psychooncology 13:792-799, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohan EA: Removing the stress from selecting instruments: Arming social workers to take leadership in routine distress screening implementation. J Psychosoc Oncol 30:667-678, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ehlers SL, Davis K, Bluethmann SM, et al. : Screening for psychosocial distress among patients with cancer: Implications for clinical practice, healthcare policy, and dissemination to enhance cancer survivorship. Transl Behav Med 9:282-291, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiss T, Weinberger MI, Holland J, et al. : Falling through the cracks: A review of psychological distress and psychosocial service needs in older Black and Hispanic patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 3:163-173, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ng D, Gallaway MS, Huang GC, et al. : Partnering with healthcare facilities to understand psychosocial distress screening practices among cancer survivors: Pilot study implications for study design, recruitment, and data collection. BMC Health Serv Res 21:238, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care (2016 Edition). https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/standards [Google Scholar]

- 41.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer : Optimal Resources for Cancer Care 2020 Standards. 2020 (With 2021 Update). https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/standards/2020 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oktay JS, Rohan EA, Burruss K, et al. : Oncology social work intervention index (OSWii): An instrument to measure oncology social work interventions to advance research. J Psychosoc Oncol 39:143-160, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greene FL, Balch CM, Fleming ID, et al. : JCC Cancer Staging Handbook: TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors (ed 7). Springer Science & Business Media, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 44.International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM), Lyon, France. cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breslow NE, Day NE: Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume I—The analysis of case-control studies. IARC Sci Publ 5-338, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarone RE: On heterogeneity tests based on efficient scores. Biometrika 72:91-95, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 47.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer : Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. 2012. http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.html [Google Scholar]

- 48.Acquati C, Kayser K: Addressing the psychosocial needs of cancer patients: A retrospective analysis of a distress screening and management protocol in clinical care. J Psychosoc Oncol 37:287-300, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zebrack B, Kayser K, Bybee D, et al. : A practice-based evaluation of distress screening protocol adherence and medical service utilization. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 15:903-912, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB: Progress in the implementation of NCCN guidelines for distress management by member institutions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 11:223-226, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zebrack B, Kayser K, Padgett L, et al. : Institutional capacity to provide psychosocial oncology support services: A report from the Association of Oncology Social Work. Cancer 122:1937-1945, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, et al. : Rural-urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer 119:1050-1057, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yao N, Alcala HE, Anderson R, et al. : Cancer disparities in rural appalachia: Incidence, early detection, and survivorship. J Rural Health 33:375-381, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gilbertson-White S, Perkhounkova Y, Saeidzadeh S, et al. : Understanding symptom burden in patients with advanced cancer living in rural areas. Oncol Nurs Forum 46:428-441, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Neil ME, Henley SJ, Rohan EA, et al. : Lung cancer incidence in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties—United States, 2007-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68:993-998, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charlton M, Zahnd W, Patterson J, et al. : Federal agencies' investment in rural cancer control fosters partnerships between researchers and rural communiites. Rural Monitor 2021. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/rural-monitor/rural-cancer-control/

- 57.John DA, Kawachi I, Lathan CS, et al. : Disparities in perceived unmet need for supportive services among patients with lung cancer in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. Cancer 120:3178-3191, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samuel CA, Mbah OM, Elkins W, et al. : Calidad de Vida: A systematic review of quality of life in Latino cancer survivors in the USA. Qual Life Res 29:2615-2630, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zebrack B, Kayser K, Sundstrom L, et al. : Psychosocial distress screening implementation in cancer care: An analysis of adherence, responsiveness, and acceptability. J Clin Oncol 33:1165-1170, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doherty M, Miller-Sonet E, Gardner D, et al. : Exploring the role of psychosocial care in value-based oncology: Results from a survey of 3000 cancer patients and survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol 37:441-455, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sannes TS, Pirl WF, Rossi JS, et al. : Identifying patient-level factors associated with interest in psychosocial services during cancer: A brief report. J Psychosoc Oncol 39:686-693, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perry LM, Hoerger M, Sartor O, et al. : Distress among African American and White adults with cancer in Louisiana. J Psychosoc Oncol 38:63-72, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Apenteng BA, Hansen AR, Opoku ST, et al. : Racial disparities in emotional distress among cancer survivors: Insights from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J Cancer Educ 32:556-565, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eylem O, de Wit L, van Straten A, et al. : Stigma for common mental disorders in racial minorities and majorities a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 20:879, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frey Nascimento A, Tondorf T, Rothschild SI, et al. : Oncologist recommendation matters!—Predictors of psycho‐oncological service uptake in oncology outpatients. Psychooncology 28:351-357, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.FitzGerald C, Hurst S: Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 18:1-18, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feagin J, Bennefield Z: Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Soc Sci Med 103:7-14, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dehon E, Weiss N, Jones J, et al. : A systematic review of the impact of physician implicit racial bias on clinical decision making. Acad Emerg Med 24:895-904, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rhee TG, Marottoli RA, Van Ness PH, et al. : Impact of perceived racism on healthcare access among older minority adults. Am J Prev Med 56:580-585, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Davis C, Kayser K, et al. : Screening for psychosocial distress: A national survey of oncology social workers. J Psychosoc Oncol 33:34-47, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hammond WP: Psychosocial correlates of medical mistrust among African American men. Am J Community Psychol 45:87-106, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dale SK, Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, et al. : Medical mistrust is related to lower longitudinal medication adherence among African-American males with HIV. J Health Psychol 21:1311-1321, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kemet S: Insight medicine lacks—The continuing relevance of Henrietta Lacks. N Engl J Med 381:800-801, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jaiswal J, Halkitis PN: Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behav Med 45:79-85, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gamble VN: A legacy of distrust: African Americans and medical research. Am J Prev Med 9:35-38, 1993. (6 suppl) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, et al. : Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 389:1453-1463, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer : Site Visit Preparation: Pre-review Questionnaire. 2021. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/accreditation/site-visit-prep [Google Scholar]