Abstract

BACKGROUND

Understanding trends in cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and CV disease according to age, sex, race, and ethnicity is important for policy planning and public health interventions.

OBJECTIVES

The goal of this study was to project the number of people with CV risk factors and disease and further explore sex, race, and ethnical disparities.

METHODS

The prevalence of CV risk factors (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity) and CV disease (ischemic heart disease, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke) according to age, sex, race, and ethnicity was estimated by using logistic regression models based on 2013–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data and further combining them with 2020 U.S. Census projection counts for years 2025–2060.

RESULTS

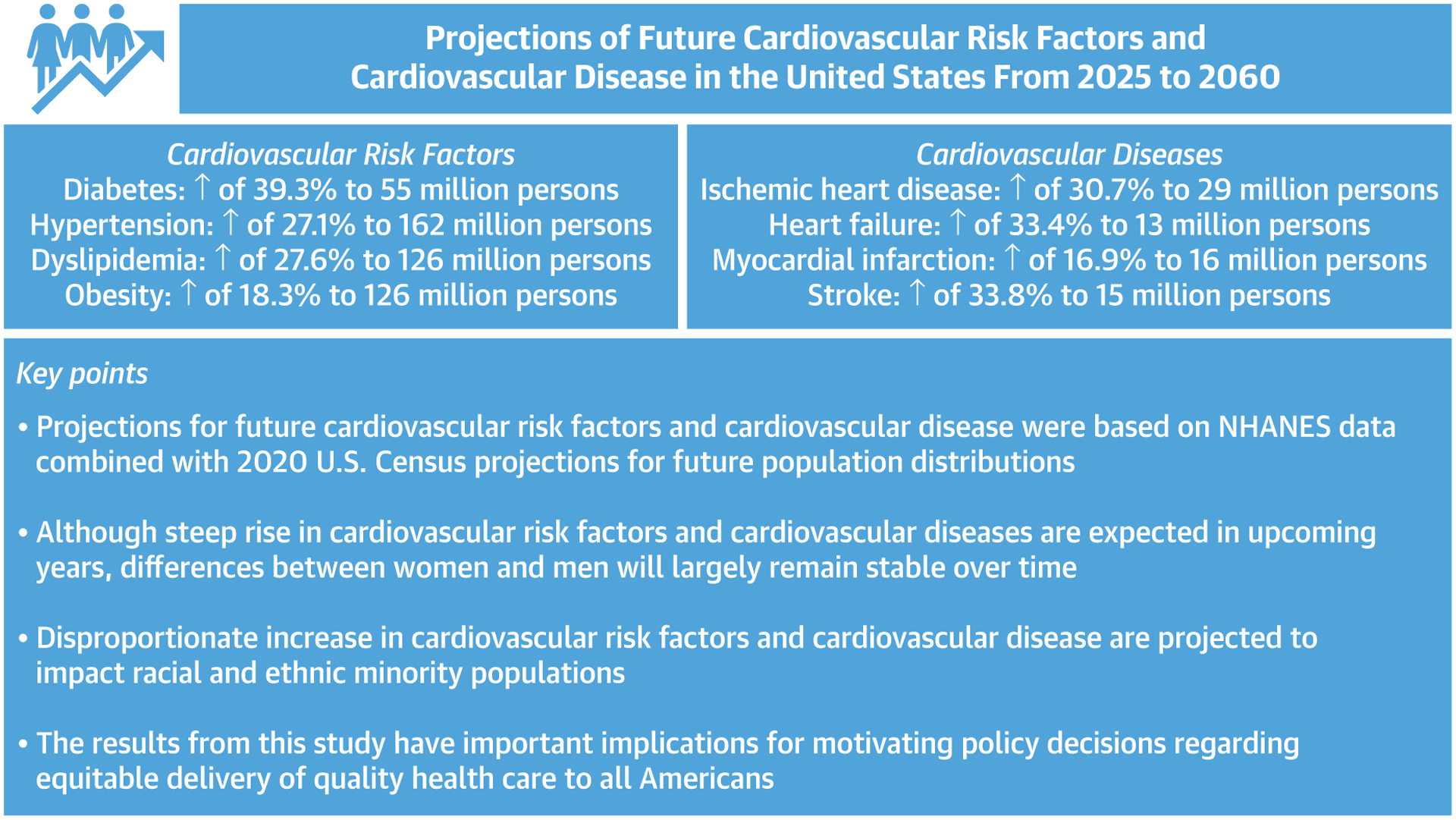

By the year 2060, compared with the year 2025, the number of people with diabetes mellitus will increase by 39.3% (39.2 million [M] to 54.6M), hypertension by 27.2% (127.8M to 162.5M), dyslipidemia by 27.5% (98.6M to 125.7M), and obesity by 18.3% (106.3M to 125.7M). Concurrently, projected prevalence will similarly increase compared with 2025 for ischemic heart disease by 31.1% (21.9M to 28.7M), heart failure by 33.0% (9.7M to 12.9M), myocardial infarction by 30.1% (12.3M to 16.0M), and stroke by 34.3% (10.8M to 14.5M). Among White individuals, the prevalence of CV risk factors and disease is projected to decrease, whereas significant increases are projected in racial and ethnic minorities.

CONCLUSIONS

Large future increases in CV risk factors and CV disease prevalence are projected, disproportionately affecting racial and ethnic minorities. Future health policies and public health efforts should take these results into account to provide quality, affordable, and accessible health care.

Keywords: ethnicity, heart disease, population health, projection, race, sex

With changes in lifestyle and increases in cardiovascular (CV) risk factors such as diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity during the past 50 years, increased incidence and prevalence of ischemic heart disease (IHD), heart failure (HF), myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke have occurred globally. Although preventive measures and public health initiatives encouraging healthy lifestyle modifications led to substantial declines in CV mortality rates and a gradual increase in the age at first CV event,1,2 the aging of the population together with an increase in DM and obesity incidence undermine these gains.3–5

An understanding of preventative strategies and therapies for CV risk factors and CV disease has improved; however, it is important to determine secular trends in CV risk factor and disease development to project future needs for prevention and treatment efforts and to identify higher risk subgroups of the population who could benefit from focused preventive and therapeutic measures.6 To better plan such efforts, factors including population growth (eg, birth rates, international immigration, mortality) must be considered. Furthermore, because health-related disparities affect the prevalence of CV risk factors and CV disease, population trends in race and ethnicity must also be considered.

With an aging U.S. population expected to grow in racial and ethnic diversity,7 a need exists to estimate the domestic prevalence of CV risk factors and disease among racial/ethnic subgroups to inform efforts toward prevention or treatment. Using 2020 U.S. Census projection data, we sought to forecast trends in the prevalence of CV risk factors and CV disease in the adult population of the United States and to examine the potential impact of sex, race, and ethnicity differences in each.

METHODS

Data from the 2013–2018 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) were used to provide an updated, population-based estimate for the prevalence of CV risk factors and disease in the general adult (age ≥18 years) population. Using a complex multistage design, the survey is asked of 5,000 persons each year who are selected from 15 of ~3,000 counties across the country and includes an interview, physical examination, and specimen collection; the interview component includes information about demographic characteristics and health-related conditions (self-reported diagnosis by health professionals of CV risk factors or diseases, among others). Physical examinations include medical, dental, and physiological measurements. Blood and urine samples are collected from all participants. The National Center for Health Statistics ethics review board approved all NHANES protocols. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS.

In NHANES, prevalence of DM was defined by a glycosylated hemoglobin value ≥6.5% or self-reported past diagnosis of DM or taking glucose-lowering medications. The prevalence of hypertension was defined by using blood pressure measurements during physical examination (systolic blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥80 mm Hg) or the responses to interview questions about being told of having high blood pressure or taking blood pressure medications. Dyslipidemia was defined based on self-report or taking cholesterol-lowering medication. Obesity was defined by a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2. The prevalence of IHD was based on patient self-report during an interview that asked about IHD, angina, and MI. The prevalence of HF and stroke was also based on patient self-report.

STATISTICAL METHODS.

The “survey” package in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was used to account for the complex sampling design of the NHANES study. Sample weights were used in the required analyses. Using NHANES data from 2013 to 2018, logistic regression models were developed adjusting for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and survey years as independent variables and each CV risk factor and CV disease as a dependent variable. Furthermore, we assessed and included any significant interactions between demographic characteristics in the model. To account for stability and generaliz-ability of our results, we calculated the 95% CI of the prevalence estimates by performing bootstrap resampling 1,000 times and providing CIs for the projections. Using predictions from these logistic regression models, the prevalence of each CV risk factor or disease was estimated in each of 40 groups of sex (male and female), age category (18–44, 45–64, 65–79, and ≥80 years), and race and ethnicity (Asian, Black, Hispanic, White, and Other [Alaska Native, Native American, Native Hawaiian, Other Pacific Islanders, and those with 2 or more races]).

We next combined these prevalence estimates with U.S. Census projections of population counts (provided for each age/sex/race and ethnicity group) for years 2025–2060 using data released by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2020, to project the number of people with prevalent CV risk factors or CV disease through 2060.8 The projections are based on assumptions about future births, deaths, and net international immigration.9 To integrate prevalence estimates with U.S. Census projection counts, the predicted prevalence of each CV risk factor or condition in each sex/age/race and ethnicity group was multiplied by the projected population counts in the corresponding groups for years 2025–2060 to project the number of people with CV risk factors or disease in each cell according to 5-year blocks. To consider the percentage of change in both CV risk factors and disease, the following was used:

All P values reported are 2-sided. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed by using R version 3.6.2.

RESULTS

The projected population sizes according to race and ethnicity across years 2025–2060 are presented in Supplemental Table 1. The estimated prevalence of each CV risk factor or disease in each of 40 categories of sex (male and female), age group (18–44, 45–64, 65–79, and ≥80 years), and race and ethnicity (Asian, Black, Hispanic, White, and Other) is detailed in Supplemental Table 2. These prevalence estimates expressed as a function of 2020 U.S. projected number of individuals based on 2020 U.S. census estimates according to age, sex, race, and ethnicity groups are detailed in Supplemental Table 3.

CV RISK FACTORS.

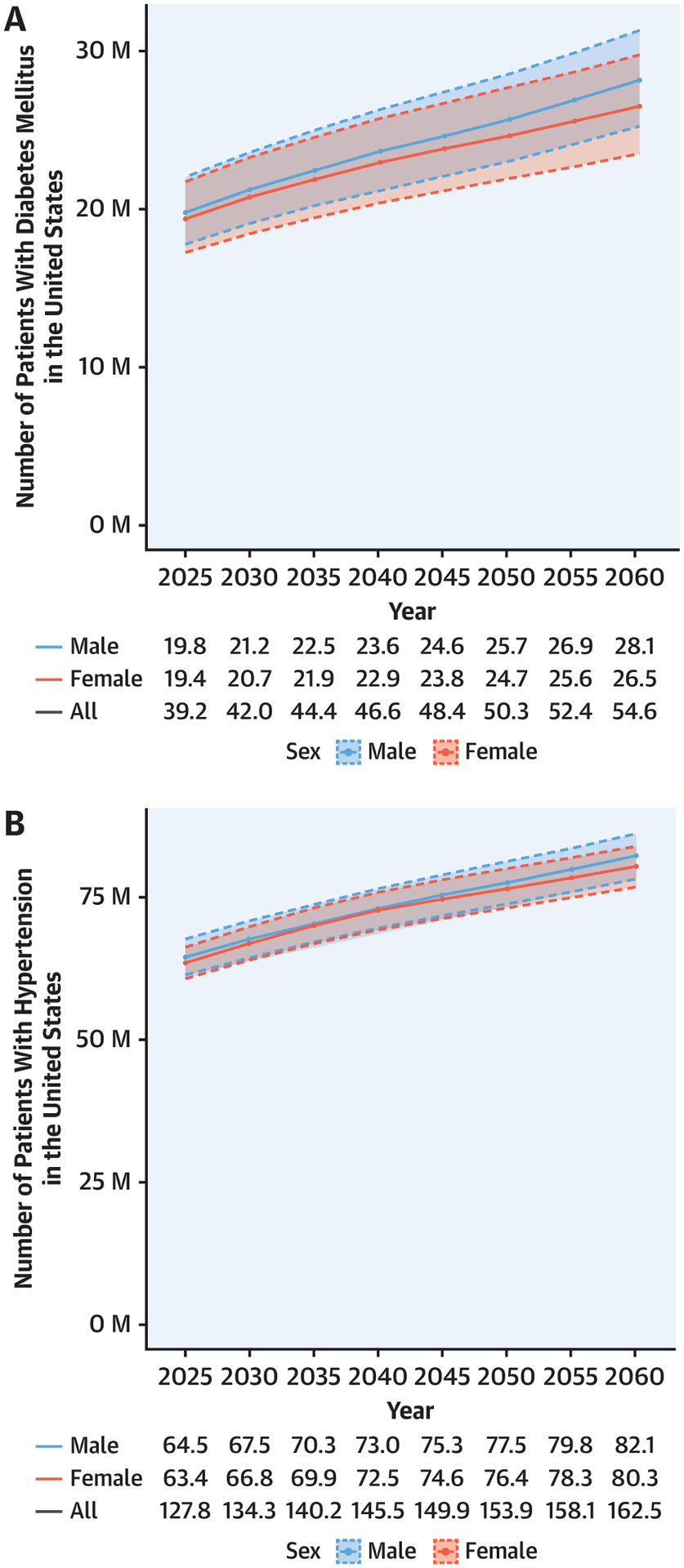

Figure 1 shows the projected overall prevalence of CV risk factors from 2025 to 2060 among the general U.S. population. By the year 2060, the prevalence of CV risk factors is estimated to rise: DM, 39.3% increase compared with 2025 (16.8% of the population or 54.6 million persons); hypertension, 27.1% increase compared with 2025 (50.1% of the population or 162.5 million persons); dyslipidemia, 27.6% increase compared with 2025 (38.7% of the population or 125.7 million persons); and obesity, 18.3% increase compared with 2025 (38.8% of the population or 125.7 million persons). The fastest rate of increase in DM, hypertension, and dyslipidemia is projected to occur between the years 2025 and 2030. The prevalence of obesity is projected to decrease slightly from 39.4% in 2025 to 38.8% in 2060, although the absolute number of individuals with obesity is expected to rise. As shown in Figure 1, apart from obesity (for which women are projected to continue to have higher prevalence), differences in projected prevalence of other CV risk factors are generally negligible between women and men.

FIGURE 1. Projected Number (95% CI) of Adults With CV Risk Factors, 2025–2060.

Diabetes mellitus (A), hypertension (B), dyslipidemia (C), and obesity (D). Under each figure is provided the total number in millions (M) and stratified according to sex. CV = cardiovascular.

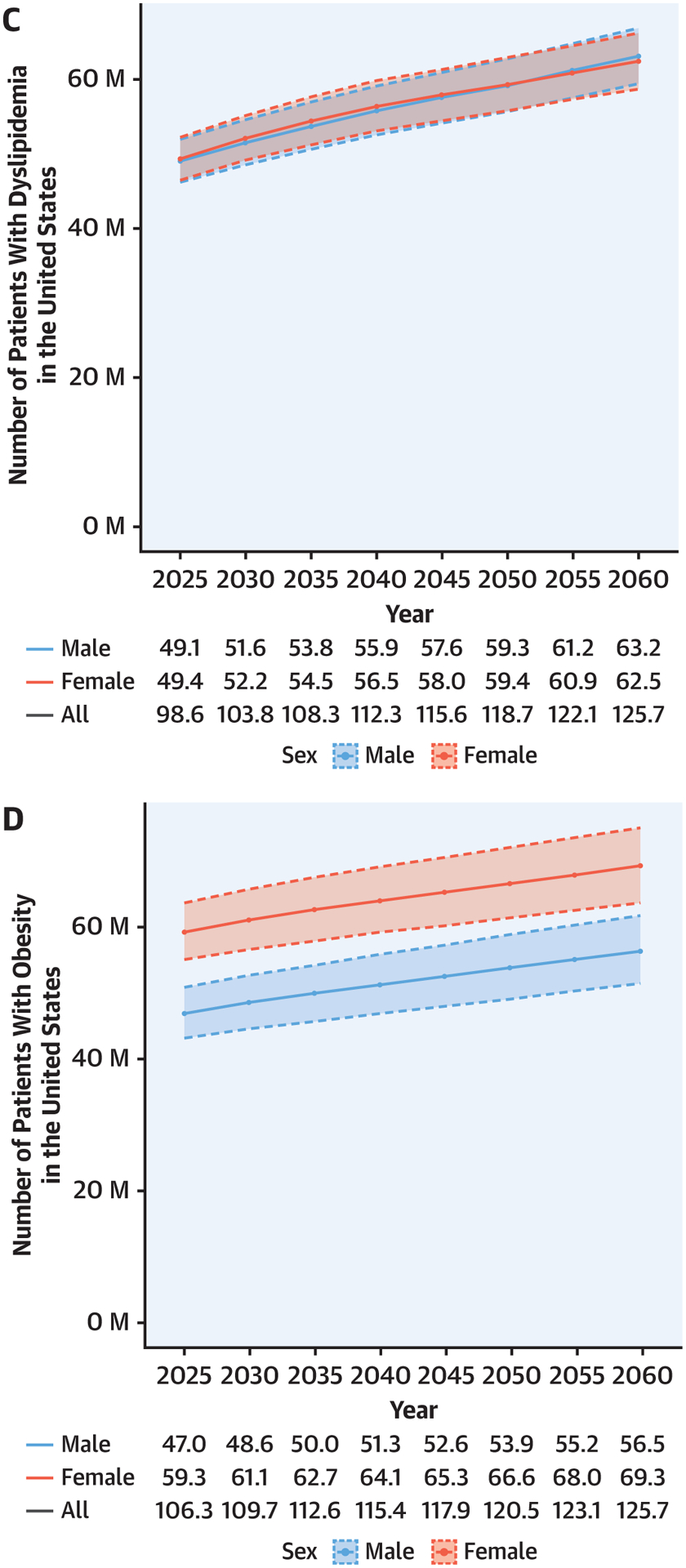

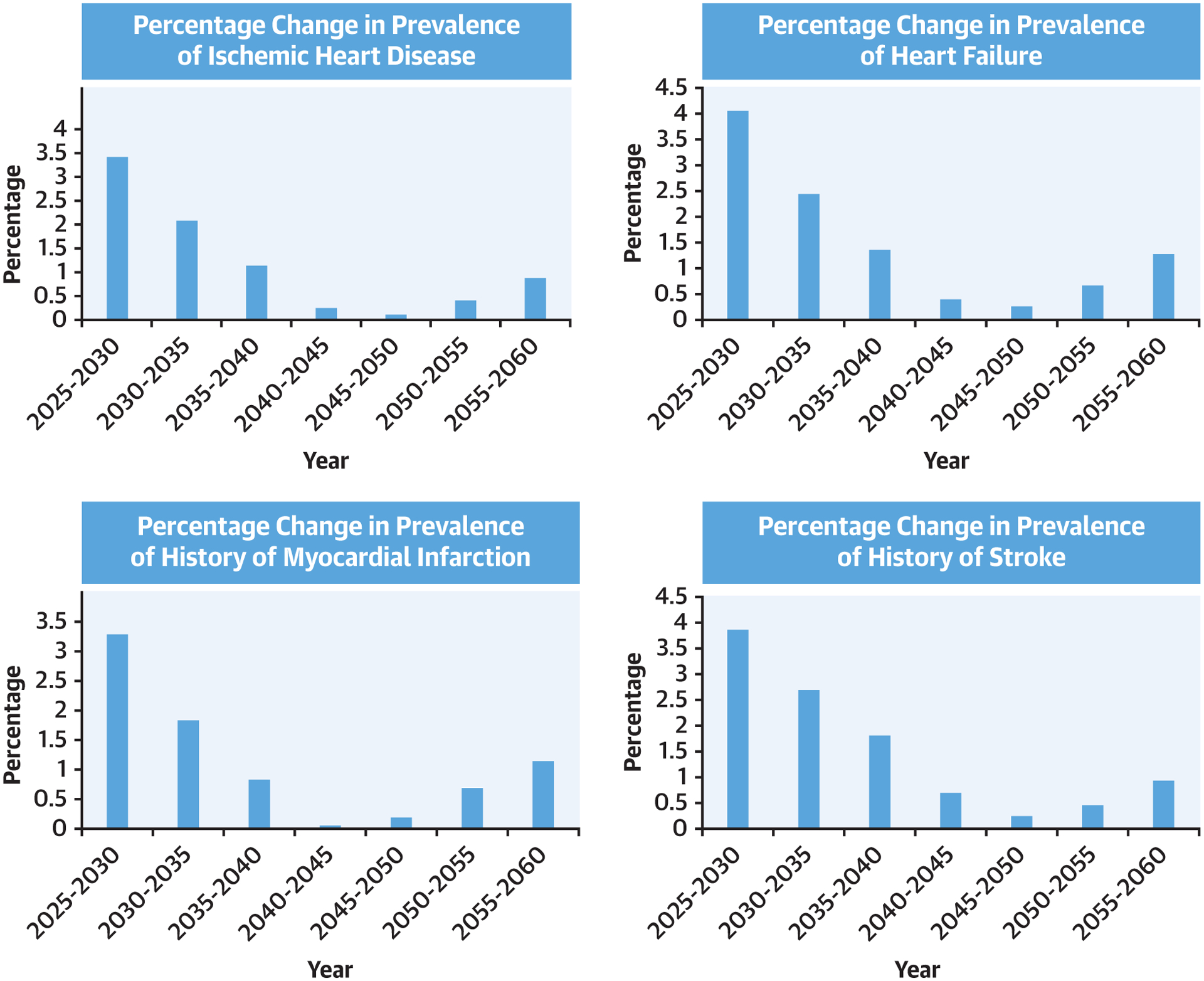

The projected change in the prevalence of each CV risk factor during the 5-year blocks shows a noteworthy pattern across decades: the most rapid increase in prevalence is projected between 2025 and 2030, then slows until 2045 or 2050, after which the increase in prevalence grows more quickly again for CV risk factors (except obesity) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Percent Change in Prevalence of CV Risk Factors Every 5 Years.

Percentage change was calculated as: [prevalence (at the end of 5 years) – prevalence (in the beginning of 5 years)]/prevalence (in the beginning of 5 years) × 100. The greatest percent changes in prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors are expected to occur between 2025 and 2030.

CV DISEASES.

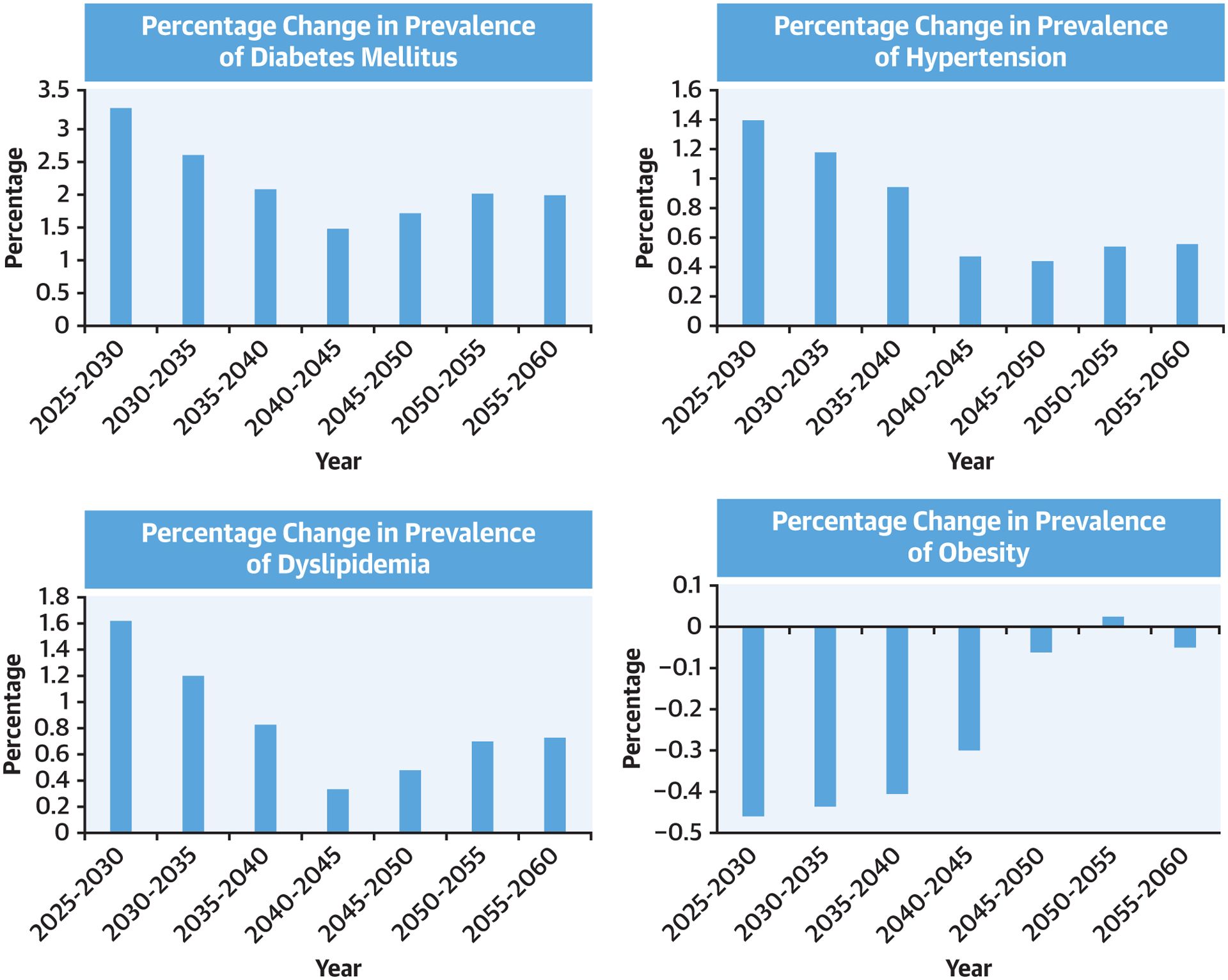

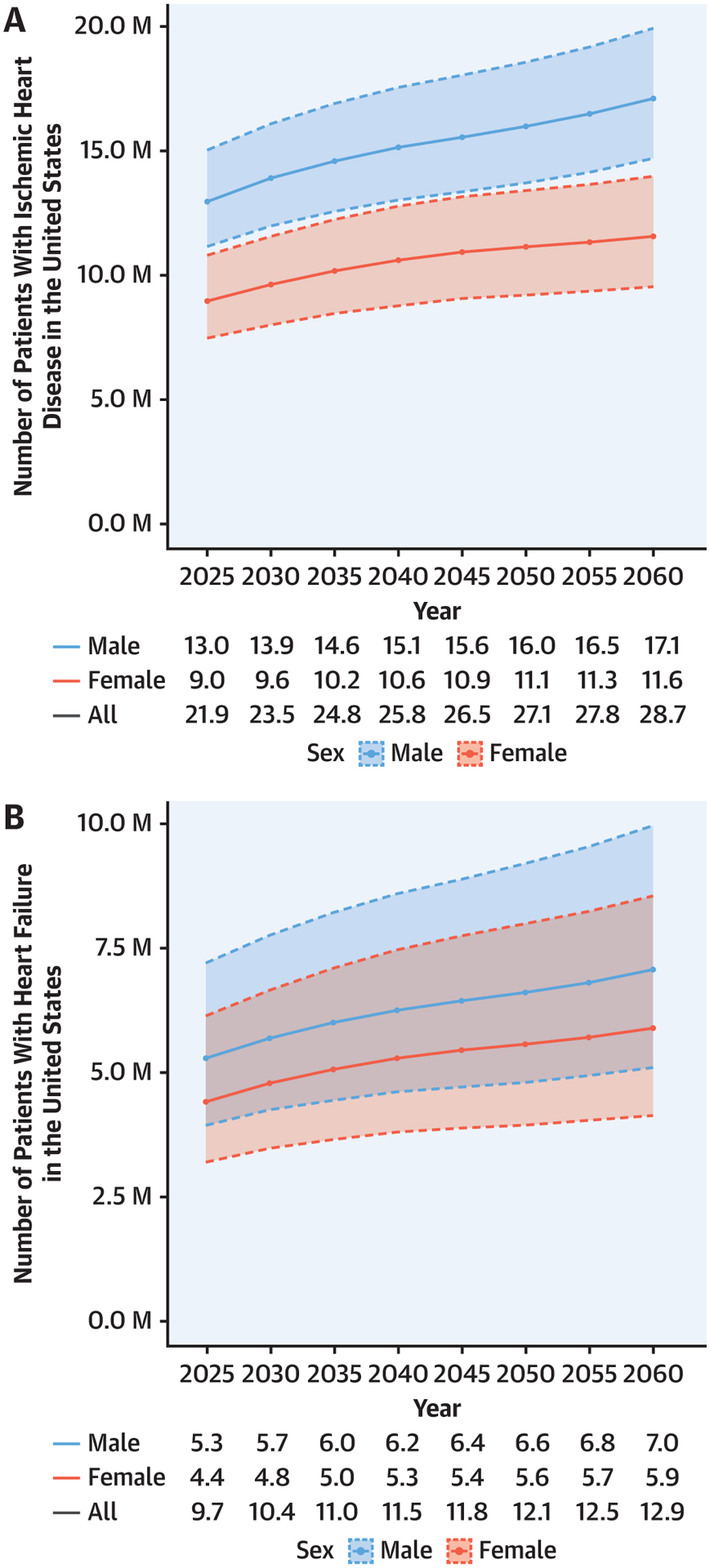

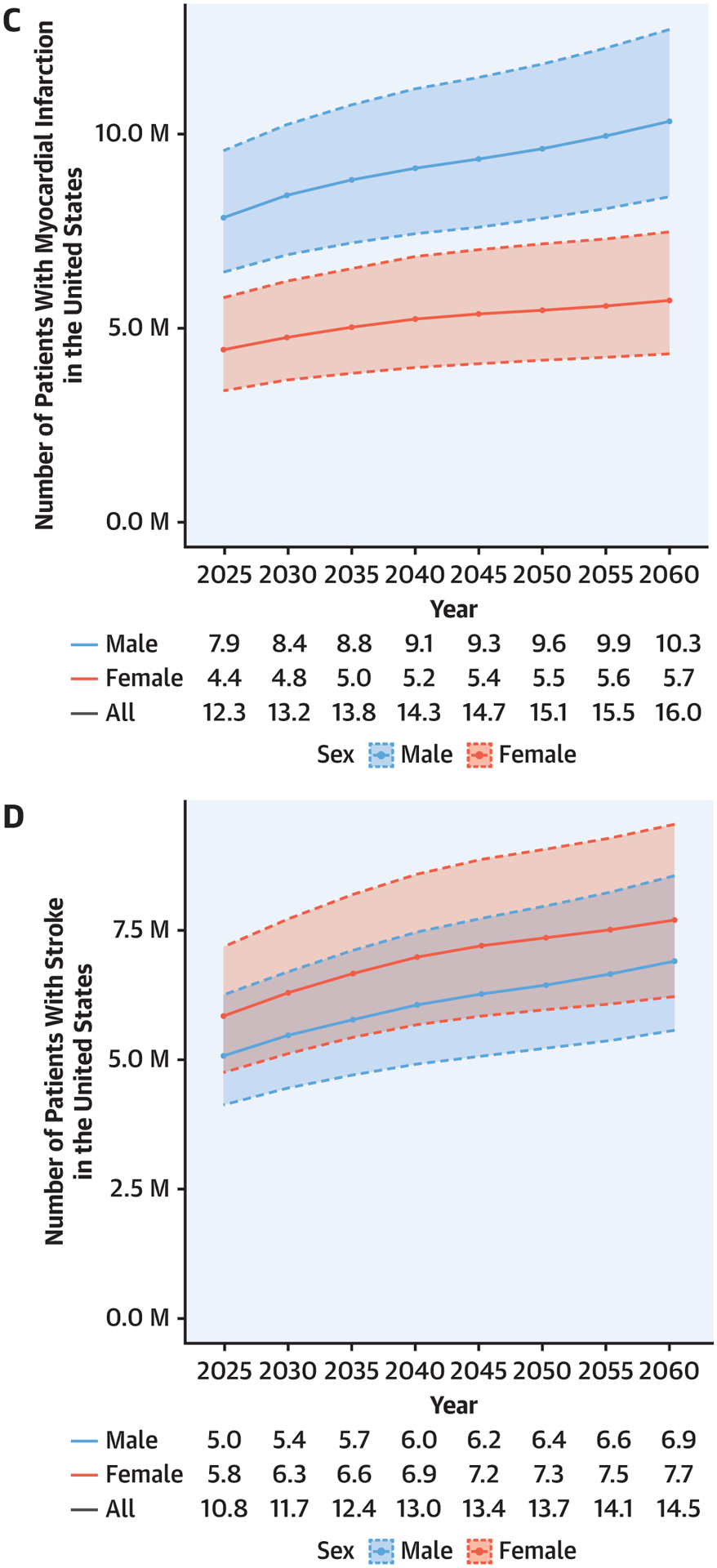

Figure 3 details the projected prevalence of CV diseases by 2060. The prevalence is projected to rise for IHD (30.7% increase compared with 2025; 8.8% of the population or 28.7 million persons), HF (33.4% increase compared with 2025; 4.0% of the population or 12.9 million persons), MI (16.9% increase compared with 2025; 4.9% of the population or 16.0 million persons), and stroke (33.8% increase compared with 2025; 4.5% of the population or 14.5 million persons). As shown in Figure 3, men will have a higher prevalence of IHD and MI compared with women, but the projected change in CV disease prevalence among both sexes over time is similar. The change in each CV disease prevalence during 5-year blocks exhibits a noteworthy pattern across decades: between 2040 and 2050, projections show a state of little or no change before rising again in 2050. The highest rate of increase is projected to occur between 2025 and 2030 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3. Projected Number (95% CI) of Adults With CV Disease, 2025–2060.

Ischemic heart disease (A), heart failure (B), myocardial infarction (C), and stroke (D). Under each figure is provided the total number in millions and stratified according to sex. CV = cardiovascular.

FIGURE 4. Percent Change in Prevalence of CV Diseases Every 5 Years.

Percentage change was calculated as: [prevalence (at the end of 5 years) – prevalence (in the beginning of 5 years)]/prevalence (in the beginning of 5 years) × 100. The greatest percent changes in prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) diseases are expected to occur between 2025 and 2030.

PROJECTED CHANGE ACCORDING TO RACE AND ETHNICITY.

Distribution of projected prevalence and race and ethnic-specific prevalence (within one’s group) of CV risk factors according to race and ethnicity through 2060 are shown in Table 1. By 2060, the highest prevalence of CV risk factors will remain among the White population due to its overall size, despite a gradual decrease in prevalence of CV risk factors. Conversely, the projected prevalence of CV risk factors is expected to rise among all other race and ethnicities. As an example, the projected race- and ethnic-specific prevalence of DM, hypertension, and obesity will be highest in the Black population starting from 2025 and increasing further through 2060; in 2060, 19.8% of all Black adults are projected to have DM, 59.9% to have hypertension, 35.9% to have dyslipidemia, and 45.6% to have obesity. The percent change in race- and ethnic-specific prevalence of CV risk factors and CV disease is further detailed in Supplemental Table 4, which shows a rise in race- and ethnic-specific CV risk factor burden in racial and ethnic minority groups. For DM, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, Hispanic persons are projected to have the largest increase in prevalence by 2060.

TABLE 1.

Projected Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors From 2025 Through 2060 as a Function of Race and Ethnicity

| Years | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | 2055 | 2060 | |||||||||

| Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | |

| Diabetes | ||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 2.9 | 16.0 | 3.3 | 16.6 | 3.6 | 17.2 | 3.9 | 17.8 | 4.3 | 18.3 | 4.6 | 18.8 | 4.9 | 19.2 | 5.2 | 19.6 |

| White | 8.2 | 13.5 | 8.1 | 13.9 | 7.9 | 14.1 | 7.6 | 14.1 | 7.3 | 14.1 | 7.1 | 14.2 | 6.9 | 14.3 | 6.7 | 14.5 |

| Black | 2.1 | 17.2 | 2.2 | 17.7 | 2.3 | 18.2 | 2.4 | 18.7 | 2.5 | 18.9 | 2.5 | 19.1 | 2.6 | 19.4 | 2.7 | 19.8 |

| Asian | 1.0 | 15.3 | 1.1 | 15.8 | 1.2 | 16.3 | 1.3 | 16.7 | 1.4 | 17.0 | 1.5 | 17.3 | 1.5 | 17.5 | 1.6 | 17.8 |

| Others | 0.4 | 13.4 | 0.4 | 13.5 | 0.4 | 13.6 | 0.5 | 13.8 | 0.5 | 14.0 | 0.6 | 14.2 | 0.7 | 14.5 | 0.7 | 14.8 |

| All | 14.5 | - | 15.0 | - | 15.4 | - | 15.7 | - | 15.9 | - | 16.2 | - | 16.5 | - | 16.8 | - |

| Hypertension | ||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 7.1 | 38.9 | 7.8 | 39.8 | 8.5 | 40.7 | 9.2 | 41.7 | 9.9 | 42.6 | 10.6 | 43.3 | 11.2 | 44.0 | 11.8 | 44.7 |

| White | 29.6 | 49.1 | 29.1 | 50.0 | 28.4 | 50.6 | 27.5 | 50.9 | 26.5 | 51.0 | 25.5 | 51.2 | 24.6 | 51.3 | 23.8 | 51.5 |

| Black | 6.9 | 55.7 | 7.0 | 56.5 | 7.2 | 57.5 | 7.5 | 58.4 | 7.6 | 58.9 | 7.8 | 59.2 | 7.9 | 59.5 | 8.1 | 59.9 |

| Asian | 2.6 | 40.4 | 2.8 | 41.4 | 3.1 | 42.3 | 3.3 | 43.1 | 3.5 | 43.6 | 3.7 | 44.1 | 3.9 | 44.5 | 4.1 | 44.9 |

| Others | 1.2 | 45.7 | 1.4 | 45.9 | 1.5 | 46.2 | 1.6 | 46.7 | 1.8 | 47.1 | 2.0 | 47.4 | 2.1 | 48.0 | 2.3 | 48.5 |

| All | 47.4 | - | 48.1 | - | 48.6 | - | 49.1 | - | 49.3 | - | 49.6 | - | 49.8 | - | 50.1 | - |

| Dyslipidemia | ||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 5.6 | 30.9 | 6.2 | 31.8 | 6.8 | 32.6 | 7.4 | 33.6 | 8.0 | 34.4 | 8.6 | 35.1 | 9.1 | 35.8 | 9.6 | 36.4 |

| White | 24.1 | 40.0 | 23.7 | 40.7 | 23.1 | 41.2 | 22.4 | 41.4 | 21.5 | 41.5 | 20.8 | 41.6 | 20.1 | 41.8 | 19.5 | 42.1 |

| Black | 3.9 | 31.9 | 4.1 | 32.7 | 4.2 | 33.5 | 4.4 | 34.3 | 4.5 | 34.7 | 4.6 | 35.0 | 4.7 | 35.4 | 4.8 | 35.9 |

| Asian | 2.1 | 32.4 | 2.3 | 33.3 | 2.5 | 34.1 | 2.7 | 34.8 | 2.9 | 35.2 | 3.0 | 35.7 | 3.2 | 36.2 | 3.3 | 36.6 |

| Others | 0.8 | 29.7 | 0.9 | 29.8 | 1.0 | 30.1 | 1.1 | 30.4 | 1.2 | 30.7 | 1.3 | 31.1 | 1.4 | 31.6 | 1.5 | 32.1 |

| All | 36.6 | - | 37.1 | - | 37.6 | - | 37.9 | - | 38.0 | - | 38.2 | - | 38.5 | - | 38.8 | - |

| Obesity | ||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 7.9 | 43.6 | 8.5 | 43.5 | 9.1 | 43.4 | 9.6 | 43.3 | 10.0 | 43.2 | 10.5 | 43.2 | 11.0 | 43.1 | 11.4 | 43.1 |

| White | 23.7 | 39.3 | 22.7 | 39.1 | 21.8 | 38.9 | 20.9 | 38.7 | 20.0 | 38.6 | 19.3 | 38.6 | 18.6 | 38.6 | 17.9 | 38.7 |

| Black | 5.7 | 46.1 | 5.7 | 46.0 | 5.8 | 45.9 | 5.9 | 45.9 | 5.9 | 45.9 | 6.0 | 45.8 | 6.1 | 45.8 | 6.1 | 45.6 |

| Asian | 0.9 | 14.1 | 1.0 | 14.0 | 1.0 | 13.9 | 1.1 | 13.8 | 1.1 | 13.7 | 1.2 | 13.7 | 1.2 | 13.6 | 1.2 | 13.5 |

| Others | 1.2 | 44.6 | 1.3 | 44.6 | 1.4 | 44.5 | 1.6 | 44.5 | 1.7 | 44.5 | 1.8 | 44.5 | 2.0 | 44.5 | 2.1 | 44.6 |

| All | 39.4 | - | 39.3 | - | 39.1 | - | 38.9 | - | 38.8 | - | 38.8 | - | 38.8 | - | 38.8 | - |

Values are %.

RE = prevalence of disease within specific race and ethnic group; Total = prevalence of disease in the total population.

Projected race and ethnicity distribution of prevalence and race- and ethnic-specific CV disease prevalence is detailed in Table 2. The projected prevalence of CV diseases will decrease for the White population and rise in all other race/ethnicities, leading to higher race- and ethnic-specific prevalence and greater rates of increase for IHD, MI, HF, and stroke, particularly in the Black and Hispanic populations.

TABLE 2.

Projected Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease From 2025 Through 2060 as a Function of Race and Ethnicity

| Year | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | 2055 | 2060 | |||||||||

| Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | Total | RE | |

| IHD | ||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 1.0 | 5.3 | 1.1 | 5.5 | 1.2 | 5.8 | 1.4 | 6.1 | 1.5 | 6.4 | 1.6 | 6.6 | 1.7 | 6.8 | 1.8 | 7.0 |

| White | 6.0 | 9.9 | 6.1 | 10.4 | 6.0 | 10.7 | 5.9 | 10.9 | 5.7 | 10.9 | 5.5 | 11.0 | 5.3 | 11.1 | 5.2 | 11.2 |

| Black | 0.7 | 5.9 | 0.8 | 6.2 | 0.8 | 6.5 | 0.9 | 6.7 | 0.9 | 6.8 | 0.9 | 6.9 | 0.9 | 7.1 | 1.0 | 7.3 |

| Asian | 0.3 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 4.2 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 4.4 | 0.4 | 4.5 | 0.4 | 4.7 | 0.4 | 4.8 |

| Others | 0.2 | 7.7 | 0.2 | 7.8 | 0.3 | 8.0 | 0.3 | 8.1 | 0.3 | 8.2 | 0.3 | 8.3 | 0.4 | 8.4 | 0.4 | 8.6 |

| All | 8.1 | - | 8.4 | - | 8.6 | - | 8.7 | - | 8.7 | - | 8.7 | - | 8.8 | - | 8.8 | - |

| Heart failure | ||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.4 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 2.9 |

| White | 2.5 | 4.2 | 2.6 | 4.4 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 4.6 | 2.4 | 4.6 | 2.3 | 4.7 | 2.3 | 4.7 | 2.2 | 4.7 |

| Black | 0.5 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 4.1 | 0.5 | 4.3 | 0.6 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 0.6 | 4.6 | 0.6 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 4.8 |

| Asian | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 1.8 |

| Others | 0.1 | 3.9 | 0.1 | 4.1 | 0.1 | 4.2 | 0.2 | 4.3 | 0.2 | 4.3 | 0.2 | 4.4 | 0.2 | 4.4 | 0.2 | 4.6 |

| All | 3.6 | - | 3.7 | - | 3.8 | - | 3.9 | - | 3.9 | - | 3.9 | - | 3.9 | - | 4.0 | - |

| MI | ||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.5 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 3.7 |

| White | 3.4 | 5.6 | 3.4 | 5.9 | 3.4 | 6.0 | 3.3 | 6.1 | 3.2 | 6.1 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 3.0 | 6.2 | 2.9 | 6.3 |

| Black | 0.4 | 3.3 | 0.4 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 3.7 | 0.5 | 3.8 | 0.5 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 0.6 | 4.2 |

| Asian | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 2.1 |

| Others | 0.1 | 5.3 | 0.2 | 5.4 | 0.2 | 5.5 | 0.2 | 5.6 | 0.2 | 5.6 | 0.2 | 5.7 | 0.3 | 5.9 | 0.3 | 6.1 |

| All | 4.6 | - | 4.7 | - | 4.8 | - | 4.8 | - | 4.8 | - | 4.9 | - | 4.9 | - | 4.9 | - |

| Stroke | ||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.4 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 0.7 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 3.0 |

| White | 2.8 | 4.6 | 2.8 | 4.8 | 2.8 | 5.0 | 2.8 | 5.1 | 2.7 | 5.2 | 2.6 | 5.2 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 2.4 | 5.2 |

| Black | 0.6 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 5.0 | 0.7 | 5.2 | 0.7 | 5.4 | 0.7 | 5.5 | 0.7 | 5.6 | 0.8 | 5.7 | 0.8 | 5.8 |

| Asian | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 1.9 |

| Others | 0.2 | 5.5 | 0.2 | 5.6 | 0.2 | 5.7 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 0.2 | 5.9 | 0.3 | 6.0 | 0.3 | 6.2 |

| All | 4.0 | - | 4.2 | - | 4.3 | - | 4.4 | - | 4.4 | - | 4.4 | - | 4.4 | - | 4.5 | - |

Values are %.

IHD = ischemic heart disease; MI = myocardial infarction; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Accounting for changes to demographic characteristics in the United States over the next 40 years, this analysis projects that the prevalence of CV risk factors and CV diseases will continue to rise, with worrisome trends (Central Illustration). Although differences between women and men will remain largely stable over time, projected increased prevalence of CV risk factors and CV diseases will disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minority populations. Understanding these concerning findings may help to inform future decisions regarding public health and policy efforts to implement prevention and treatment measures in a more equitable manner.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Projected Future of Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Cardiovascular Diseases by 2060.

Dramatic increases in risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia are projected to disproportionately affect ethnic and racial minority groups, resulting in a parallel rise of ischemic heart disease and heart failure in these populations.

A particularly striking result in this analysis is the projected prevalence of DM affecting Black and Hispanic populations; such a rise may be multifactorial, including immigration and growth of these populations and disparities in socioeconomic status and other social determinants of health, along with a continued increase in risk factors such as gestational diabetes and environmental risks.10–12 In a similar manner, prevalence of hypertension is projected to increase during this time frame, with a rate of increase greatest in populations already with a high prevalence of the diagnosis.13 As well, continuing trends seen in NHANES 2015–2018 (in which nearly 12% of adults aged ≥20 years had total cholesterol levels >240 mg/dL),14 the number of persons with dyslipidemia are projected in this analysis to increase to 126 million individuals (38.76%) by 2060, with the highest rate of projected increase in prevalence among Hispanic individuals. As clinical practice guidelines have continuously expanded prevention criteria for diagnoses such as dyslipidemia,15 these results may not be stable; however, those persons with poor access to health care are more likely to go unscreened or untreated, further exposing them to risk of developing CV disease.

Somewhat unexpectedly, a slight decrease was projected in the prevalence of obesity, from 39.4% to 38.8% (−1.3%). These results differ from others16 that did not consider the effect of aging of the population, future immigration patterns, future birth, and death rates. One explanation for the divergent results might be loss of lean body mass in an aging U.S. population, something reflected in the decreased prevalence of obesity among the elderly population as shown in Supplemental Table 1.

In parallel with an increase in CV risk factors, the prevalence of IHD and MI is projected to increase by 2060, with the greatest rates of increase in the prevalence of IHD projected in Black and Hispanic persons, consistent with a disproportionate projected rise of CV risk factors and relatively earlier age of onset of CV disease in these groups.17 As well, projected HF prevalence is expected to continue to rise substantially, also with relative increases disproportionately affecting Black and Hispanic populations, groups with low representation in clinical trials of HF therapies18 and experiencing substantial gaps in treatment.19 Lastly, stroke will also be increasingly common among multiple racial and ethnic minority groups, owing to shared risk factors with other CV diseases; these at-risk populations are also more likely to experience stroke at a younger age and develop recurrent stroke.20

The results from this study suggest an ongoing shift in prevalence of CV disease that was initially predicted from the 2008 U.S. Census by Heidenreich et al21 using the same methodology but with even more worrisome projections to the year 2060. Although other studies have attempted to predict the future of CV disease,22,23 they are limited due to using preceding trends rather than the most contemporary census counts and NHANES data, and they do not consider the influence of changing demographic characteristics in sex, race, and ethnicity.

The results of this analysis have financial implications, particularly because the cost of treatment for prevalent CV disease is greater than the cost of preventative strategies. With rising total numbers of risk factors and CV disease disproportionately affecting an aging population from populations with restricted access to quality preventative care, the potential burden on the U.S. health care system is large. However, the results from the current analysis assume no modification in health care policies or other changes in access to care for at-risk populations: reducing health disparities in health care literacy, preventative care, and treatment of CV disease might be expected to attenuate projected trends and minimize rise in costs.24 Emphasis on education regarding CV risk factors, improving access to quality health care, and facilitating lower cost access to effective therapies for treatment of CV risk factors may stem the rising tide of CV disease in at-risk individuals; such advances need to be applied in a more equitable way throughout the United States, however. The results from this study may serve as a motivator to policy development to improve health care access to historically neglected populations and may motivate the implementation of preventive strategies using a more customized approach.25 Improved risk stratification, interventions focused on improving socioeconomic status, and provision of better access to affordable health care will be critical. Emphasis on ethnocultural empathy and awareness will also be critical, to better address the root causes of CV risk factor differences in growing and changing populations. Given that impact of structural racism is associated with CV risk factors,26 treatment access, and clinical outcomes and spans many domains, including access to care, socioeconomic status, insurance coverage, and residential environment, a critical evaluation and dismantling of systems that have left racial and ethnic minority populations with inferior care is essential to reduce inequities and improve CV health for all.

STUDY LIMITATIONS.

Importantly, in generating predictions for future CV disease, the approach used assumes that patterns of CV risk factors and CV disease according to age/sex/race and ethnicity group will continue for the duration of the time examined. This conventional method assumes that any current estimate of the disease will cease at the beginning of the forecast period, and the prevalence is held constant when projecting numbers of cases into the future. This method has been used by several high-impact efforts to estimate future disease, including from the International Diabetes Federation,27 Heidenreich et al,21 Huovinen et al,28 Odden et al,29 Huffman et al,30 Heidenreich et al,31 Ovbiagele et al,32 and Nelson et al.33 Lending credence to the results of this study, the near-term projections in our estimates for the year 2030 were entirely consistent with the outer horizon of estimates from Heidenreich et al28; although we have derived our CVD prevalence estimate from a different NHANES data set and different U.S. census counts, our projection numbers were similar. This implies the accuracy and reproducibility of the method. Importantly, in multivariable logistic regression, age, sex, and ethnicity (but not survey year) were associated with CV disease. This implies that demographic factors are determinants of CV disease rather than the survey year. Second, we did not take into account the effect of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) on our estimates; nearly 1 million deaths caused by COVID-19 have occurred so far in the United States, and many individuals have been left with morbid complications of the diagnosis. The long-term consequences of COVID-19 on the CV system remain unclear, but this is an obvious concern.34 Importantly, minoritized populations have been disproportionality affected by COVID-19, which may further influence our projections.35 Third, CV diseases were defined based on self-report, which is important as some populations with limited health literacy may not self-report past illness with the same frequency.36 Moreover, self-reporting can potentially lead to many epidemiologic biases, including misclassification, ascertainment, and survivor bias, which can ultimately affect our projection results. This is a fundamental bias embedded in NHANES. However, NHANES is one of the most accurate survey data sets available, and the methodology used is consistent with other efforts similar to ours.37–42 Clair et al43 compared 2 methods of measuring disease prevalence: 1) using self-reported disease from survey responses; and 2) using disease diagnosis codes from administrative data. Multiple sources were included: Medicare claims data, NHANES, and the Health and Retirement Study. The investigators concluded that surveys provide less biased samples and may be the preferred method because they are nationally representative. Conversely, claim data provide more accurate diagnosis and may be more suited for research on specific disease likely to be less well-defined in surveys. Lastly, we need to mention that we used history of treatment as part of the CV risk definition. This may lead to underestimation of prevalence of CV risk factors in minoritized individuals with limited health access.

CONCLUSIONS

This study projects substantial changes in the prevalence of CV risk factors and CV disease in the U.S. population by 2060, with an increasing prevalence among Black and Hispanic populations who have historically experienced poor access to quality health care. Targeted efforts toward improved screening and equitable access to quality health care in populations with the greatest growth in CV risk factors or disease would be expected to have a substantial impact to reduce future CV risk for the population overall.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN SYSTEMS-BASED PRACTICE:

Substantial increases in the prevalence of CV risk factors and manifest disease are expected to disproportionately affect populations with limited access to health care.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK:

Strategies are needed for health care professionals and policy makers to target preventive and treatment measures to specific populations at greatest risk.

FUNDING SUPPORT AND AUTHOR DISCLOSURES

Dr Mohebi is supported by the Barry Fellowship. Dr McCarthy is supported by a National. Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute T32 postdoctoral training grant (5T32HL094301-12). Dr Hyle is supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG069575). Dr Januzzi is supported by the Hutter Family Professorship. Dr Ibrahim has received honoraria from Cytokinetics, Medtronic, Novartis, and Roche. Dr Gaggin has received research grant support from Roche Diagnostics, Jana Care, Ortho Clinical, Novartis, Pfizer, Alnylam, and Akcea; has received consulting income from Amgen, Eko, Merck, Roche Diagnostics, and Pfizer; has stock ownership for Eko; has received research payments for clinical endpoint committees from Radiometer; and has received research payment for clinical endpoint committees from the Baim Institute for Clinical Research for Abbott, Siemens, and Beckman Coulter. Dr Singer receives research support from Bristol Myers Squibb; and has received consulting income from Bristol Myers Squibb, Fitbit, Medtronic, and Pfizer. Dr Wasfy is supported by a grant from the American Heart Association (18 CDA 34110215); and has received consulting income from Pfizer and Bio-tronik. Dr Januzzi is supported by the Hutter Family Professorship; is a Trustee of the American College of Cardiology; is a board member of Imbria Pharmaceuticals; has received grant support from Abbott Diagnostics, Applied Therapeutics, Innolife, and Novartis; has received consulting income from Abbott Diagnostics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics; and participates in clinical endpoint committees/data safety monitoring boards for AbbVie, Siemens, Takeda, and Vifor. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease-2019

- CV

cardiovascular

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- HF

heart failure

- IHD

ischemic heart disease

- MI

myocardial infarction

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

APPENDIX For supplemental tables, please see the online version of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mackenbach JP. The epidemiologic transition theory. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 1994;48(4):329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olshansky SJ, Ault AB. The fourth stage of the epidemiologic transition: the age of delayed degenerative diseases. Milbank Q. 1986:355–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magliano DJ, Islam RM, Barr ELM, et al. Trends in incidence of total or type 2 diabetes: systematic review. BMJ. 2019;366:l5003. 10.1136/bmj.l5003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254–e743. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(9):873–898. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. Curr Pop Rep. 2015:1125–1143. [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau releases national population projections reports on life expectancy and alternative migration scenarios. Accessed February 13, 2020. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/population-projections.html.

- 9.U.S. Census Bureau. Population projections for 2020 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.pdf.

- 10.Lawrence JM, Divers J, Isom S, et al. Trends in prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents in the US, 2001–2017. JAMA. 2021;326(8):717–727. 10.1001/jama.2021.11165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deputy NP, Kim SY, Conrey EJ, Bullard KM. Prevalence and changes in preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes among women who had a live birth—United States, 2012–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(43):1201–1207. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thayer KA, Heindel JJ, Bucher JR, Gallo MA. Role of environmental chemicals in diabetes and obesity: a National Toxicology Program workshop review. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(6):779–789. 10.1289/ehp.1104597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foti K, Wang D, Appel LJ, Selvin E. Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in US adults: trends in the hypertension control cascade by population subgroup (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2016). Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(12):2165–2174. 10.1093/aje/kwz177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult obesity facts. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html.

- 15.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(24): e285–e350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, et al. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(25):2440–2450. 10.1056/NEJMsa1909301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carnethon MR, Pu J, Howard G, et al. Cardiovascular health in African Americans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(21):e393–e423. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azam TU, Colvin MM. Representation of Black patients in heart failure clinical trials. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2021;36(3):329–334. 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewsey SC, Breathett K. Racial and ethnic disparities in heart failure: current state and future directions. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2021;36(3):320–328. 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamel H, Zhang C, Kleindorfer DO, et al. Association of black race with early recurrence after minor ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: secondary analysis of the POINT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(5):601–605. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(8):933–944. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huffman MD, Capewell S, Ning H, Shay CM, Ford ES, Lloyd-Jones DM. Cardiovascular health behavior and health factor changes (1988–2008) and projections to 2020: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Circulation. 2012;125(21):2595–2602. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.070722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandya A, Gaziano TA, Weinstein MC, Cutler D. More Americans living longer with cardiovascular disease will increase costs while lowering quality of life. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1706–1714. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Essien UR, Dusetzina SB, Gellad WF. A policy prescription for reducing health disparities—achieving pharmacoequity. JAMA. 2021;326(18):1793–1794. 10.1001/jama.2021.17764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schultz WM, Kelli HM, Lisko JC, et al. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular outcomes: challenges and interventions. Circulation. 2018;137(20):2166–2178. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30569-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):137–149. 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huovinen E, Harkanen T, Martelin T, Koskinen S, Aromaa A. Predicting coronary heart disease mortality—assessing uncertainties in population forecasts and death probabilities by using Bayesian inference. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(5): 1246–1252. 10.1093/ije/dyl128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Odden MC, Coxson PG, Moran A, Lightwood JM, Goldman L, Bibbins-Domingo K. The impact of the aging population on coronary heart disease in the United States. Am J Med. 2011;124(9):827–833. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.04.010. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huffman MD, Lloyd-Jones DM, Ning H, et al. Quantifying options for reducing coronary heart disease mortality by 2020. Circulation. 2013;127(25):2477–2484. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–619. 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ovbiagele B, Goldstein LB, Higashida RT, et al. Forecasting the future of stroke in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(8):2361–2375. 10.1161/STR.0b013e31829734f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson SA. Projections of cardiovascular disease prevalence and costs. https://www.heart.org/-/media/Files/Get-Involved/Advocacy/CVD-Predictions-Through-2035.pdf.

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home.

- 35.Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, Sia IG, Wieland ML. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(4):703–706. 10.1093/cid/ciaa815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu Y, Liu Y, Dhingra LS, et al. National trends in racial and ethnic disparities in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among adults with hypertension, 2011–2018. Hypertension. 2022;79(1):207–217. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rethy L, Petito LC, Vu THT, et al. Trends in the prevalence of self-reported heart failure by race/ethnicity and age from 2001 to 2016. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(12):1425–1429. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He J, Ogden LG, Bazzano LA, Vupputuri S, Loria C, Whelton PK. Risk factors for congestive heart failure in US men and women: NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(7):996–1002. 10.1001/archinte.161.7.996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gartside PS, Wang P, Glueck CJ. Prospective assessment of coronary heart disease risk factors: the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study (NHEFS) 16-year follow-up. J Am Coll Nutr. 1998;17(3):263–269. 10.1080/07315724.1998.10718757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saydah S, Bullard KM, Cheng Y, et al. Trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors by obesity level in adults in the United States, NHANES 1999–2010. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(8):1888–1895. 10.1002/oby.20761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo F, Garvey WT. Trends in cardiovascular health metrics in obese adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1988–2014. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(7). 10.1161/JAHA.116.003619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ford ES. Trends in mortality from all causes and cardiovascular disease among hypertensive and nonhypertensive adults in the United States. Circulation. 2011;123(16):1737–1744. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.005645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.St Clair P, Gaudette E, Zhao H, Tysinger B, Seyedin R, Goldman DP. Using self-reports or claims to assess disease prevalence: it’s complicated. Med Care. 2017;55(8):782–788. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.