Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) first reported in Wuhan, China in December 2019 is a global pandemic that is threatening the health and wellbeing of people worldwide. To date there have been more than 274 million reported cases and 5.3 million deaths. The Omicron variant first documented in the City of Tshwane, Gauteng Province, South Africa on 9 November 2021 led to exponential increases in cases and a sharp rise in hospital admissions. The clinical profile of patients admitted at a large hospital in Tshwane is compared with previous waves.

METHODS

466 hospital COVID-19 admissions since 14 November 2021 were compared to 3962 admissions since 4 May 2020, prior to the Omicron outbreak. Ninety-eight patient records at peak bed occupancy during the outbreak were reviewed for primary indication for admission, clinical severity, oxygen supplementation level, vaccination and prior COVID-19 infection. Provincial and city-wide daily cases and reported deaths, hospital admissions and excess deaths data were sourced from the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, the National Department of Health and the South African Medical Research Council.

RESULTS

For the Omicron and previous waves, deaths and ICU admissions were 4.5% vs 21.3% (p<0.00001), and 1% vs 4.3% (p<0.00001) respectively; length of stay was 4.0 days vs 8.8 days; and mean age was 39 years vs 49,8 years.

Admissions in the Omicron wave peaked and declined rapidly with peak bed occupancy at 51% of the highest previous peak during the Delta wave.

Sixty two (63%) patients in COVID-19 wards had incidental COVID-19 following a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test . Only one third (36) had COVID-19 pneumonia, of which 72% had mild to moderate disease. The remaining 28% required high care or ICU admission. Fewer than half (45%) of patients in COVID-19 wards required oxygen supplementation compared to 99.5% in the first wave. The death rate in the face of an exponential increase in cases during the Omicron wave at the city and provincial levels shows a decoupling of cases and deaths

compared to previous waves, corroborating the clinical findings of decreased severity of disease seen in patients admitted to the Steve Biko Academic Hospital.

CONCLUSION

There was decreased severity of COVID-19 disease in the Omicron-driven fourth wave in the City of Tshwane, its first global epicentre.

Keywords: NICD, National Institute of Communicable Diseases (South Africa); NDOH, National Department of Health (South Africa); SAMRC, South African Medical Research Council; SBAH, Steve Biko Academic Hospital; UP, University of Pretoria

Keywords: Omicron, COVID-19, Tshwane, disease severity, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) first reported in Wuhan China in December 2019, is a global pandemic that is threatening the health and wellbeing of people worldwide. To date there have been more than 274 million reported cases and 5.3 million deaths (World Health Organisation 2021). South Africa has borne the brunt of COVID-19 on the African continent, registering in excess of 3 million cases and 90 000 officially reported deaths (National Department of Health 2021). The number of deaths could be as high as 275,976 (Bradshaw et al., 2021), putting this country's death toll among the highest in the world with a cumulative excess death rate of 464 per 100,000. South Africa is currently experiencing its fourth COVID-19 wave, being driven by the recently identified Omicron variant. Previous waves were associated with the Ancestral, Beta and Delta variants.

The City of Tshwane (incorporating Pretoria and surrounding areas just north of Johannesburg), with its population of 3.31 million people (Office of the Executive Mayor 2021) has had 241,794 cases of SARS-CoV-2, 35 090 hospital admissions and 7,086 deaths (National Institute for Communicable Diseases 2021) since the first COVID-19 admission at the Steve Biko Academic Hospital on 4 May 2020.

The first case of Omicron was documented in the City of Tshwane on 9 November 2021 (World Health Organization 2021). This was followed by a rapid rise in SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 associated hospitalisations from 14 November 2021, heralding the onset of the fourth wave in South Africa. Omicron rapidly displaced the Delta variant in the City of Tshwane and the Gauteng Province of South Africa (Network for Genomics Surveillance in South Africa (NGS-SA) 2021).

During the resurgence in Tshwane, we observed a difference in the clinical picture of COVID-19 ward patients compared with prior COVID-19 waves. We report from the first global epicentre of Omicron-driven resurgence on the patient profile of admissions to the Steve Biko Academic Hospital in Pretoria, the heart of the Tshwane District. In the current study, we compare the clinical profile of 466 COVID-19 patients admitted in the first 33 days since the commencement of the Omicron driven fourth wave with that of 3962 patients admitted during the 3 pandemic waves over the previous 18 months since May 2020 and provide a description of the clinical profile of 98 patients in the hospital at the peak of the Omicron wave on 14-15 December 2021.

METHODS

The Steve Biko Academic Hospital (SBAH) is an 800 bed tertiary academic hospital to which is attached the 240-bed Tshwane District Hospital and the University of Pretoria's Health Sciences Faculty. Sections of the hospital, including ICU, high care and general wards were repurposed for the management of adult and paediatric COVID-19 patients. This included areas in the Emergency Units, labour wards and theatres. All clinical departments provided both staff and services to the COVID-19 areas as required.

At the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020, a national hospital admissions surveillance system (DATCOV) was established by the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD). Hospital level data were extracted from the COVID-19 hospital surveillance system for patients admitted to the Steve Biko Academic Hospital (SBAH) from 4 May 2020 to 16 December 2021. These hospital records were reviewed for a comparison between patients admitted during the Omicron wave and previous waves. All patients were included in the sample.

466 records from DATCOV of patients admitted during the Omicron wave were compared to all 3962 records of patients admitted during three previous waves over a period of 18 months. In addition, a snapshot analysis of 98 records of patients occupying COVID-19 beds in the hospital at peak bed occupancy were reviewed for severity of illness, primary indication for admission, oxygen supplementation level, self-reported vaccination and prior COVID-19 infection status. These data were entered into the internal hospital information system. Oxygen supplementation levels for 588 patients admitted to the hospital during the first wave were reviewed (Boswell et al., 09 December 2021).

The record files of 21 deceased patients for the period 14 November through 16 December 2021 were requested from the hospital registries and reviewed for cause of death.

Hospital COVID-19 bed occupancy was obtained from daily statistics captured by the Nursing Services Manager responsible for bed management at the facility.

Data for the city and province-wide cases, deaths and hospital admissions were provided by the NDOH (National Department of Health 2021) and the NICD (National Institute for Communicable Diseases 2021). Data analysis was done using Excel and STATA 16. Data smoothing was performed using LOWESS in STATA 16 (Stata/IC 16 2020).

RESULTS

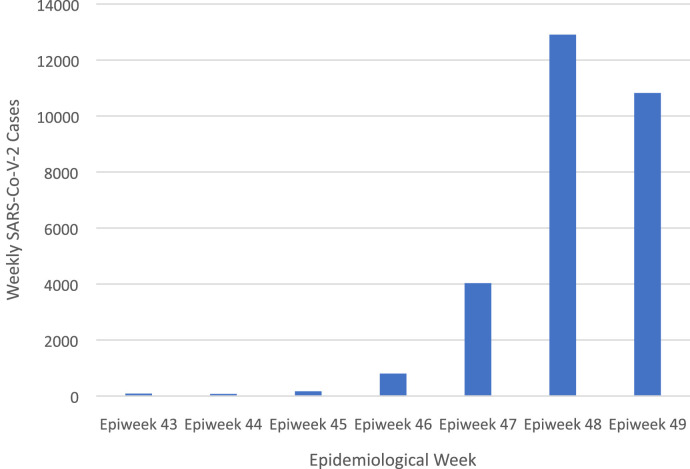

There was an exponential increase in SARS-CoV-2 infections in the City of Tshwane, commencing in the week of 7 November 2021 as shown in Figure 1, reaching 11 010 cases in the week of 28 November 2021 and peaking in the week of 5 December 2021.

Figure 1.

Weekly number of SARS-CoV-2 cases in Tshwane District, 24 October through 11 December 2021 (NICD)

The highest single day occupancy of COVID beds during the Omicron wave was 108 on 13 December 2021, much lower than the highest level of COVID bed occupancy over previous waves, which was 213 beds occupied on 13 July 2021 at the peak of the Delta wave.

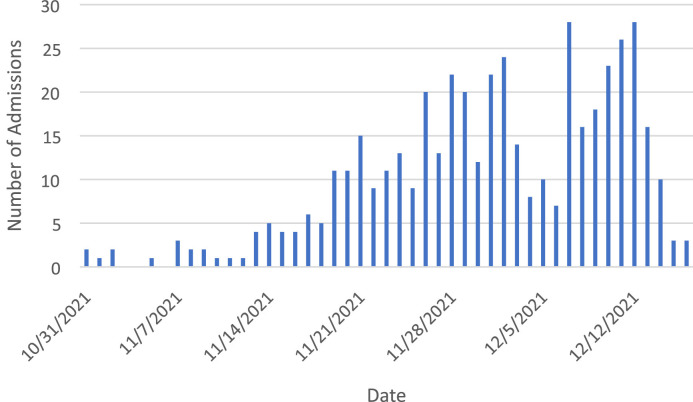

There were 466 admissions to the COVID-19 wards between 14 November and 16 December 2021 compared to 20 admissions in the preceding two weeks, showing the rapid rise in hospital admissions during this period (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Daily number of COVID-19 hospital admissions for Steve Biko Academic Hospital, 31 October to 16 December 2021

Table 1 compares 466 patients admitted during the Omicron wave and 3962 during previous waves, showing significant differences in the age distribution, outcomes, level of care required, and length of hospital stay. Mean age was significantly lower (39 vs 49.8 years), most admissions were in the 30 – 39 year age group, 68% of admissions were for those below age 50 compared to 44.5% previously, and the proportion of admissions in 0-9 year old age group doubled.

Table 1.

Description of COVID-19 admissions at Steve Biko Academic Hospital Complex, fourth wave compared to previous waves

| INDICATORS | 14/11/21 – 16/12/21 | 4/5/2020-13/11/21 | TEST PARAMETER | SIGNIFICANCE LEVEL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n(%) or mean(SD) | n(%) or mean(SD) | |||

| # Admissions | 466 | 3962 | ||

| Mean age | 39(22.4) | 49.8(21.8) | t= - 10.2 | p< 0.00001 |

| Proportions in age groups | ||||

| 0-9 | 62(13.3) | 284(7.17) | z= 5.1 | p< 0.00001 |

| 10-19 | 17(3.7) | 91(2.3) | z = 2 | P = 0.044 |

| 20-29 | 83(17.8) | 255(6.4) | z=8.8 | p< 0.00001 |

| 30-39 | 105(22.5) | 551(13.9) | z=5.1 | p< 0.00001 |

| 40-49 | 49(10.5) | 582(14.7) | z= - 1.9 | p = 0.15 |

| <50 | 316(67.8) | 1763(44.5) | Z=8.9 | p< 0.00001 |

| >=50 | 150(32.2) | 2169(54,7) | Z=-8.9 | p< 0.00001 |

| 50-59 | 41(8.8) | 757(19.1) | z = -5.5 | p< 0.00001 |

| 60-69 | 68(14.6) | 797(20.1) | z= -2.7 | P = 0.0061 |

| 70+ | 41(8.8) | 615(15.5) | z= -5.1 | p< 0.00001 |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 30 (0.8) | ||

| Length of stay | 4.0(3.7) | 8.8(19) | t = - 5.4 | p< 0.00001 |

| ICU | 5(1%) | 172(4.3%) | z= -3.4 | P 0.0007 |

| Deaths | 21(4.5%) | 847(21.3%) | z= - 8.7 | P< 0.00001 |

There were 21 (4.5%) hospital deaths compared to 847 (21.3%) and 5 (1%) ICU admissions compared to 172 (4.3%) in the Omicron wave compared to previous waves. Length of hospital stay was significantly shorter (4.0 days) in the Omicron wave compared to 8.8 days in previous waves.

A cause of death analysis for 21 deceased patients in the Omicron wave at the hospital showed COVID-19 with a confirmed COVID pneumonia as the cause of death in 10 (48%) patients, another cause exacerbated by COVID pneumonia in 4 (19%), and a cause unrelated to COVID pneumonia in 7 (33%).

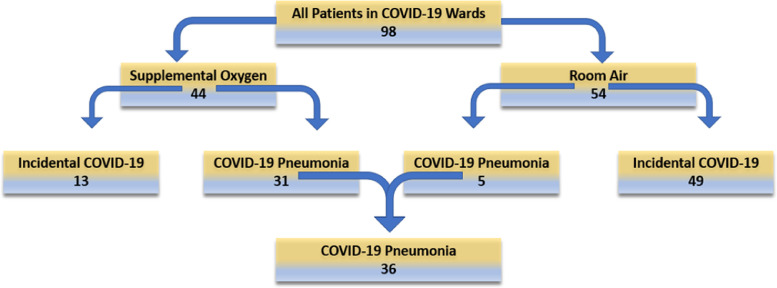

Figure 3 and Table 2 show clinical severity of 98 patients in the COVID wards on 14-15 December 2021.

Figure 3.

Tree diagram showing COVID-19 disease severity in patients at the Steve Biko Academic Hospital on 14-15 December 2021

Table 2.

Levels of oxygen supplementation for COVID pneumonia patients at Steve Biko Academic Hospital Complex 14-15 December 2021

| Oxygen Supplementation Modality | Room Air | Nasal Prongs Oxygen | Face Mask Oxygen | Double Oxygen Nasal Prongs+ Face Mask Oxygen | High Flow Nasal Oxygen | Non Invasive Ventilation | Mechanical Ventilation | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed COVID Pneumonia | 5 (14%) | 13 (36%) | 8 (22%) | 1(3%) | 1 (3%) | 4 (11%) | 4 (11%) | 36 (100%) |

Thirty-six patients (37%) had a confirmed diagnosis of COVID pneumonia, of which 31 (86%) required oxygen supplementation.

Sixty-two (63%) patients were incidental COVID admissions, having been admitted for another serious primary medical, surgical, obstetric or psychiatric diagnosis. These cases have been labelled ‘incidental COVID’ as they were diagnosed as the result of hospital admission procedures, rather than having the typical clinical profile or meeting a case definition for COVID-19. This phenomenon of ‘incidental COVID’ is not a phenomenon observed before in South Africa and most likely reflects high levels of asymptomatic disease in the community with Omicron infection. As all patients being admitted to the hospital are tested for SARS-CoV-2 as per the policy, those testing positive are admitted to the designated COVID wards.

Fifty-four patients (55%) coped on room air without supplemental oxygen. Fewer than half (45%) of patients in COVID-19 wards compared to 99.5% (Boswell et al., 09 December 2021) in the first wave required oxygen supplementation.

Table 2 shows the level of oxygen supplementation as an index of severity among patients with COVID-19 pneumonia of whom 26 (72%) required no or low levels of oxygen supplementation. Ten patients (28%) required high care or ICU admission. Among the 4 ICU admissions, 3 patients exhibited features of a COVID-19 pneumonia, however only 1 patient required invasive mechanical ventilation primarily for COVID-19 associated respiratory failure. One (1) patient required invasive mechanical ventilation for confirmed pneumonia with severe COPD and cardiogenic shock in the Emergency Care Unit. The six paediatric admissions to paediatric high care/ICU were attributed to diagnoses unrelated to COVID-19.

The Emergency Medical Unit in the SBAH complex reported a marked decline in the use of reticulated oxygen volumes compared to previous waves.

Among 55 pregnant women admitted to the COVID-19 labour ward only 2 required face-mask oxygen, mirroring the 'incidental COVID-19' picture seen in the adult and paediatric COVID-19 wards. One of these two patients had a mild COVID-19 pneumonia requiring supplemental oxygen for 3 days. The second required supplemental oxygen for a diagnosis unrelated to COVID-19.

The findings described above for the Steve Biko Academic Hospital were comparable to city-wide trends when cases and admissions from all public and private hospitals reported in the national hospital surveillance system were observed. The data from the NICD DATCOV database showed that there was a total of 33,643 SARS-CoV-2 cases, 3,233 COVID-19 hospitalisations and 130 deaths reported in the City of Tshwane in the same period (14 November to 16 December 2021), reflecting a lower admission per case ratio, lower death rate and lower rates of admission to the ICU compared to previous waves.

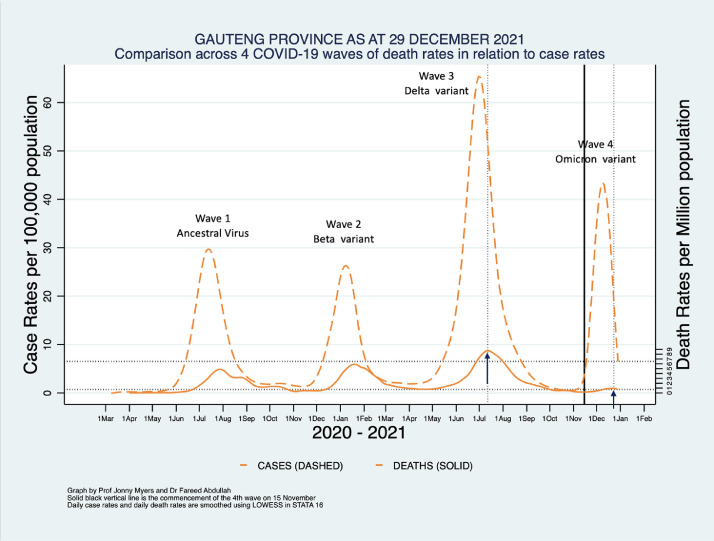

Figure 4 further shows an uncoupling of the case and death rates for the Gauteng Province as a whole, confirming the local hospital experience of significantly fewer admissions to the ICU and deaths compared to previous waves.

Figure 4.

COVID-19 cases and reported deaths rates for the Gauteng Province (National Department of Health 2021)

DISCUSSION

As it has been demonstrated elsewhere that the Omicron variant rapidly displaced Delta in the region in which this study was conducted (Viana et al., 2021), the assumption that the clinical profile described in this paper represents disease caused by the Omicron variant is reasonable. The Omicron outbreak has spread and declined in the City of Tshwane with unprecedented speed, peaking within 4 weeks of its commencement. Hospital admissions increased rapidly and began to decline within a period of 33 days. This demonstrates a significantly different transmission trajectory and epidemiological profile from that of previous variants of concern and can be expected to be replicated in other parts of the world.

Peak bed occupancy was about half that of the third (Delta) wave suggesting a lower rate of hospital admissions relative to the number of cases in the Omicron wave compared to previous waves. The mean age of hospitalized patients in the Omicron wave was 11 years younger than previous waves and may reflect the higher rate of vaccination in the elderly population. Fewer ICU admissions and deaths and a shorter length of hospital stay indicate decreased severity of disease caused by the Omicron variant. A third of deaths resulted from a cause other than COVID-19, and there were no paediatric deaths related to severe COVID-19 disease. Sixty three percent of COVID-19 patients in the snapshot at peak bed occupancy were in hospital for an alternative primary diagnosis, and were ‘incidental COVID’ patients as they were diagnosed as the result of hospital admission procedures, rather than having the typical clinical profile or meeting a case definition for COVID. This phenomenon has not been observed to this extent before in the Steve Biko Academic Hospital or anywhere in South Africa and most likely reflects high levels of asymptomatic disease in the community with Omicron infection.

The low percentage of patients in the COVID-19 wards with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia has implications for the application of clinical skill and expertise being deployed to the COVID-19 wards, with all specialties required to manage their ‘incidental COVID' patients under COVID-19 infection control standards. It also implies much lower oxygen utilization levels in the COVID-19 wards. The categorization of patients into ‘incidental SARS-CoV-2’ and moderate to severe COVID-19 disease may lead to a radically different internal organization of COVID-19 wards at the hospital.

A similar profile of patients is being seen in COVID-19 wards in the Western Cape Province of South Africa (Mendelsohn et al., 2021) and reports of similar patterns of the clinical profile of patients have been described by one of South Africa's largest private hospital groups (Maslo, 2021).

The changing clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection is likely due to high levels of prior infection and vaccination coverage in this setting. The estimated seroprevalence of immunity from prior infection and vaccine induced immunity for the City of Tshwane is 66.7% (95% CI, 54.2 to 69.0) (Madhi Shabir et al., 2021). About 36% of adults aged 18 to 49 and 58% over age 50 in the Gauteng Province are vaccinated. Another plausible cause for the lower number of admissions and decreased severity is a decrease in pathogenicity or virulence of the highly mutated Omicron variant, though more research is required to fully establish this theory.

A similar pattern is likely to emerge in other provinces in South Africa as Omicron spreads rapidly across the country, but may differ in countries where levels of hybrid immunity or the mix of immunity from prior infection and vaccination are different.

Limitations of the study include the inability to compare the Omicron wave to each of the three previous waves separately due to the difficulty of defining the beginning and end dates of previous waves. Another limitation of the study is that it was unable to compare clinical parameters of patients in the COVID-19 wards across waves due to poor electronic record-keeping of these parameters, including clinician evaluations, chest-xray finding and blood biomarkers for COVID-19 disease.

CONCLUSION

There was decreased severity of disease in the Omicron-driven fourth wave in the City of Tshwane, its first global epicentre, with fewer deaths, ICU admissions and a shorter length of hospital stay. The younger age profile of patients is likely to have been a factor of this clinical profile.

The wave increased at a faster rate than previous waves, completely displacing the Delta variant within weeks and began its decline in both cases and hospital admissions in the fifth week following its commencement.

There are clear signs that case and admission rates in South-Africa may decline further over the next few weeks. If this pattern continues and is repeated globally, we are likely to see a complete decoupling of case and death rates, suggesting that Omicron may be a harbinger of the end of the epidemic phase of the Covid pandemic, ushering in its endemic phase.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This study was supported by the South African Medical Research Council.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was granted by the University of the Witwatersrand (DATCOV MED2010093) and the University of Pretoria's Research Ethics Committee (637/2020).

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all the participants involved in this study, and all the members the Steve Biko Academic and Tshwane District Hospital for their sterling work in caring for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.12.357.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Boswell T. et al. COVID-19 severity and in-hospital mortality in an area with high HIV prevalence, 09 December 2021, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square [ https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1156502/v1 ]

- Bradshaw D. et al. Estimated natural deaths of persons 1+years. South Africa Medical Research Council. https://www.samrc.ac.za/reports/report-weekly-deaths-south-africa (accessed 20 December 2021) 2021

- Madhi Shabir A., et al. South African Population Immunity and Severe Covid-19 with Omicron Variant. Shabir A. Madhi, et al 2021, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.12.20.21268096v1

- Maslo C, et al. JAMA. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn A.S., et al. COVID-19 wave 4 in Western Cape Province, South Africa: Fewer hospitalisations, but new challenges for a depleted workforce. S Afr Med J. 2021 doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2022.v112i2.16348. Published online 21 December. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Department of Health. COVID-19 statistics in South Africa. https://sacoronavirus.co.za/ (accessed 11 December 2021) 2021

- National Institute for Communicable Diseases. https://www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/COVID-19-Weekly-Epidemiology-Brief-week-48-2021.pdf. COVID-19 Wkly. Epidemiol. BRIEF, WEEK 48 2021. https://www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/COVID-19-Weekly-Epidemiology-Brief-week-48-2021.pdf (accessed 20 December 2021) 2021.

- Network for Genomics Surveillance in South Africa (NGS-SA). SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Surveillance Update. https://www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Update-of-SA-sequencing-data-from-GISAID-17-Dec-21_Final.pdf (accessed 20 December 2021) 2021.

- Office of the Executive Mayor https://www.tshwane.gov.za/sites/Council/Ofiice-Of-The-Executive-Mayor/20162017%20IDP/01.%20Tabling%20of%20the%20City%20of%20Tshwane%202021%202026%20IDP.pdf (accessed 20 December 2021) 2021

- Stata/IC 16. 1 for Mac Revision 31 Mar 2020 https://www.stata.com/products/mac/ (accessed 23 December 2021)

- Viana R. et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. medRxiv, MEDRXIV-2021-268028v1-deOliveira: (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed 22 December 2021) 2021.

- World Health Organization. Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern (accessed Dec 10, 2021) 2021

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.