Abstract

AML1 is one of the most frequently mutated genes associated with human acute leukemia and encodes the DNA-binding subunit of the heterodimering transcriptional factor complex, core-binding factor (CBF) (or polyoma enhancer binding protein 2 [PEBP2]). A null mutation in either AML1 or its dimerizing partner, CBFβ, results in embryonic lethality secondary to a complete block in fetal liver hematopoiesis, indicating an essential role of this transcription complex in the development of definitive hematopoiesis. The hematopoietic phenotype that results from the loss of AML1 can be replicated in vitro with a two-step culture system of murine embryonic stem (ES) cells. Using this experimental system, we now demonstrate that this hematopoietic defect can be rescued by expressing the PEBP2αB1 (AML1b) isoform under the endogenous AML1-regulatory sequences through a knock-in (targeted insertion) approach. Moreover, we demonstrate that the rescued AML1−/− ES cell clones contribute to lymphohematopoiesis within the context of chimeric animals. Rescue requires the transcription activation domain of AML1 but does not require the C-terminal VWRPY motif, which is conserved in all AML1 family members and has been shown to interact with the transcriptional corepressor, Groucho/transducin-like Enhancer of split. Taken together, these data provide compelling evidence that the phenotype seen in AML1-deficient mice is due solely to the loss of transcriptionally active AML1.

Hematopoietic development in mammals is supported by two discrete cellular populations which are believed to be derived from distinct cellular origins (5, 22). In the mouse, for example, the first wave of primitive hematopoiesis emerges around day 7.5 postcoitus (E 7.5) in the yolk sac and consists primarily of large nucleated primitive erythrocytes, which diminish midgestation. By contrast, around E 9.5, the second wave of hematopoiesis emerges in the fetal liver and consists of so-called definitive hematopoietic cells, including enucleated erythrocytes containing adult-type globin molecules, myeloid cells, and lymphoid progenitors. The site of this second wave of hematopoiesis is subsequently shifted to the bone marrow and spleen prior to birth.

Recent studies have revealed that a number of transcriptional factors play critical roles in regulating the fate of the hematopoietic stem cell populations. These factors are divided into two groups: one contains factors which regulate both primitive and definitive hematopoiesis, and the other contains factors whose activities are required for the development of some or all of the definitive hematopoietic lineages (reviewed in reference 44). The acute myeloid leukemia (AML) 1 gene, AML1, belongs to the latter group and is unique in that loss of this gene in mice results in the complete absence of all definitive hematopoietic lineages (37, 51).

AML1 was originally cloned from the breakpoint of chromosome 21 in t(8;21)(q22;q22), which is associated with 40% of the AML cases of the French-British-American classification M2 subtype (6, 27, 29). AML1 has subsequently been shown to be one of the most frequent targets of leukemia-associated gene aberrations, including t(3;21), which is found in the blastic crisis of chronic myelocytic leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes (26, 31), t(12;21), which is observed in pediatric B-lineage acute lymphocytic leukemia (9, 40), and t(16;21), which is associated with secondary leukemias (7). Together, these translocations comprise ∼12% of AML cases and ∼20% of acute lymphocytic leukemia in pediatric and young adult populations (20). Moreover, recent studies have revealed that AML1 is also disrupted by several other rare chromosomal translocations (41) and is inactivated by point mutations in occasional cases of adult AML (39), thus further documenting the high prevalence of AML1 alterations in human leukemia.

AML1 encodes the DNA-binding subunit of the heterodimering transcriptional factor complex, core-binding factor (CBF) (or polyoma enhancer binding protein 2 [PEBP2]) (12, 33), and binds to the DNA sequence TGT/cGGT, which is essential for the transcriptional regulation of a number of hematopoietic specific genes, including those for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), M-CSF receptor, myeloperoxidase, neutrophil elastase, and each of the subunits of the T-cell antigen receptor genes (reviewed in references 16 and 47). AML1's DNA binding is mediated through a central 128-amino-acid domain with 69% identity to the product of the Drosophila pair-rule gene, runt (3, 13) (Runt domain), and its DNA-binding affinity is increased by binding to its heterodimeric partner CBFβ (or PEBP2β) (32, 53) through the Runt domain (12, 23). Interestingly, CBFβ has been demonstrated to be the target of the leukemia-associated chromosomal abnormalities inv(16)(p13q22) and t(16;16)(p13;q22) (19). Homozygous disruptions in either AML1 or CBFβ result in an embryonic lethal phenotype secondary to a complete block in fetal liver hematopoiesis, thus demonstrating an essential role for this transcription factor complex in normal definitive hematopoiesis (30, 37, 42, 51, 52). Moreover, recent studies have demonstrated that mice expressing the t(8;21)-encoded AML1-ETO (eleven twenty-one, or myeloid translocation gene on chromosome 8 [MTG8]) (6, 27) leukemic gene through a knock-in approach die from a similar phenotype, suggesting that this fusion protein functions at least in part as a dominant negative repressor of normal AML1-mediated transcription (34, 55). Importantly, however, fetal liver cells from AML1-ETO-expressing embryos showed abnormal differentiation and an increased self-renewal capacity, suggesting that AML1-ETO directly contributes to the promotion of early steps in leukemic transformation of the hematopoietic stem cells (34; reviewed in references 4 and 46).

In an attempt to directly define the structural features of AML1 required for its biological role in establishing definitive hematopoiesis, we examined the ability of wild-type or mutant AML1 genes to rescue the hematopoietic defect that results from the loss of AML1. Using an in vitro hematopoietic differentiation assay with murine embryonic stem (ES) cells, we now demonstrate that the C-terminal transactivation domain of AML1 is required for its biological activity. By contrast, the five C-terminal amino acids that mediate interaction with the Groucho/transducin-like Enhancer of split corepressor are not necessary for its role in early definitive hematopoiesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of the plasmids.

The full-length mouse cDNA for the AML1 gene, PEBP2αB1 (2), equivalent to human AML1b (28), was kindly provided by Yoshiaki Ito, Institute for Viral Research, Kyoto University. The deletion mutations of AML1b, at codons 293 (AML1bΔ293), 320 (AML1bΔ320), and 390 (AML1bΔ390), were introduced by cleaving the PEBP2αB1 cDNA with the restriction endonucleases SalI, SphI, and NcoI, respectively, followed by the insertion of double-stranded oligonucleotides containing stop codons in all three frames, TAATTAATTAATTA, surrounded by corresponding cohesive overhangs. To construct an AML1 mutant, AML1bΔ446, that lacks the genetic code for the C-terminal VWRPY motif, a GT-to-TA nonsense mutation was introduced at codon 447 by PCR with the primer pair 5′-TCCTACCATCTATACTACGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCCACTAGGCCTCCTCCAGG-3′ (antisense). The NcoI-restricted fragment of the resultant PCR product, which contained an artificial stop codon at residue 447, was inserted into the corresponding site of the PEBP2αB1 cDNA.

To produce replacement-type vectors for creating knock-in alleles, a genomic DNA fragment of ca. 12 kb encompassing exon 4 of the mouse AML1 gene, which corresponds to the middle of the Runt domain, was cloned into a pBluescript II plasmid vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), followed by an insertion of a diphtheria toxin-A suicide cassette (34) at the 3′ end of the insert in the sense orientation. Next, a SacII-restricted fragment from either the full-length or each of the C-terminal deletion mutants of PEBP2αB1 cDNA, accompanied by a DNA fragment of the polyadenylation signal from the rabbit globin gene, was inserted into the corresponding SacII site of exon 4 of the AML1 genomic DNA fragment so as to create an artificial exon which then contained the entire cDNA sequence of mouse AML1b (PEBP2αB1) or one of the designed mutations downstream from exon 4. Finally, a puromycin resistance cassette was inserted just downstream of the polyadenylation signal sequence for sense orientation. This cassette was constructed by replacing the neomycin phosphotransferase coding sequence of a neomycin resistance cassette (37) with the puromycin N-acetyltransferase coding sequence. The vectors were named pRES-AML1b, pRES-AML1b(Δ293), pRES-AML1b(Δ320), pRES-AML1b(Δ390), and pRES-AML1b(Δ446) and were linearized at a unique ScaI site within the cloning vector just prior to being transfected into ES cells.

To construct the eukaryotic expression vectors of hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged AML1b or its mutants, a site-directed mutagenesis was performed to introduce a T-to-G substitution at nucleotide 253 and a G-to-C substitution at nucleotide 257 of PEBP2αB1 cDNA (2) to convert the initiation codon into an isoleucine codon followed by an artificial BamHI site. The BamHI-cleaved mutant cDNA was fused to a cohesive double-stranded oligonucleotide encoding an HA peptide (sense, 5′-AGCTTGCCGCCACCATGTATGATGTTCCTGATTATGCTAGCCTCTT-3′; antisense, 5′-GATCAAGAGGCTAGCATAATCAGGAACATCATACATGGTGGCGGCA-3′) and then subcloned into the multiple-cloning site of a cytomegalovirus promoter-based eukaryotic expression vector, pRc/CMV (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). A DNA fragment downstream from the unique SacII site of PEBP2αB1 was then replaced with the corresponding fragments of the AML1 mutants to construct expression vectors for each of the mutants. The resulting plasmids were named pRc:HA-AML1b, pRc:HA-AML1b(Δ293), pRc:HA-AML1b(Δ320), pRc:HA-AML1b(Δ390), and pRc:HA-AML1b(Δ446) to indicate the name of the replacing mutant.

All ligated and mutated sites of the constructs were sequenced for both strands to confirm their integrity prior to use for the subsequent experiments.

Transient expression of AML1 proteins in COS-7 cells.

One million COS-7 cells were transfected by the DEAE-dextran method (21, 48) with 5 μg of the supercoiled plasmid DNA of each pRc construct (mentioned above). Cells were lysed for Western blot analysis after a 72-h culture.

Isolating the knock-in clones.

E14 cell clones which had undergone homologous recombination for both AML1 alleles at exon 4, with a neomycin cassette replacement vector for one allele and a hygromycin B-resistance cassette vector for the other, were cultured as previously described (37) so as to preserve the undifferentiated phenotype. Twenty micrograms of the linearized targeting vector for each of the above mentioned pRES constructs was electroporated into 107 ES cells, and the subsequent clones were selected in the presence of puromycin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at 1.3 μg/ml. Resistant clones for the targeted integration were serially evaluated by Southern blot analysis under conventional conditions (36) with 5′ and 3′ outside probes (see Fig. 1) as previously described (37). Single-copy integration of the vector DNA to the clones was then confirmed by Southern blot analysis with an internal probe corresponding to the puromycin N-acetyltransferase sequence. ES clones showing successful homologous recombination at either of the disrupted alleles were cultured for expansion and then kept frozen until further analyses.

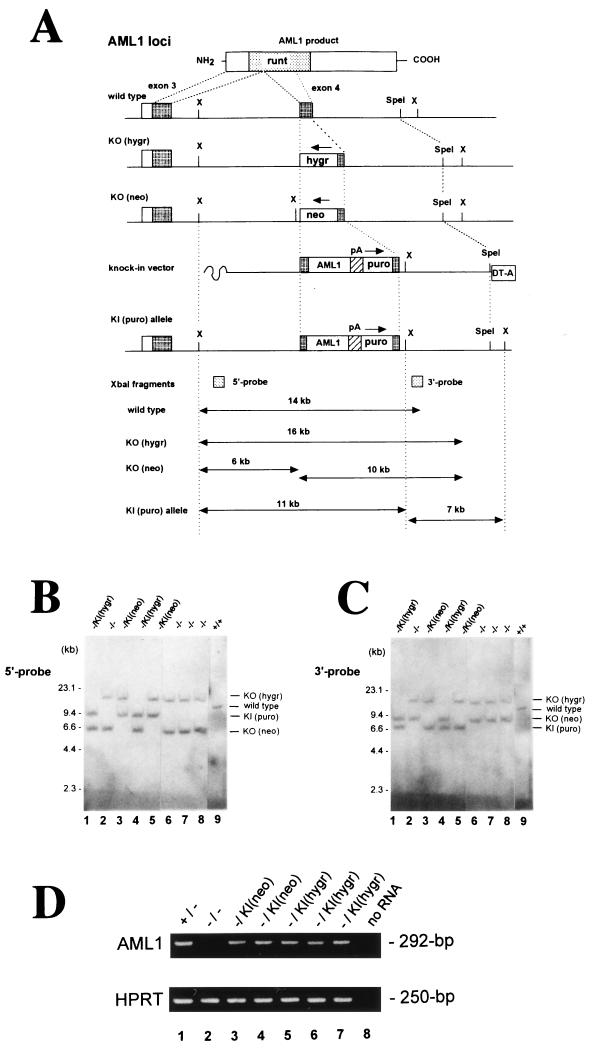

FIG. 1.

Rescue strategy of AML1-deficient ES cells by expressing PEBP2αB1 (AML1b) cDNA from a knock-in allele. (A) The AML1 loci of the ES cell lines were disrupted by targeting exon 4, which encodes the middle of the Runt domain; one allele was replaced by a hygromycin resistance cassette [KO(hygr)] and the other by a neomycin resistance cassette [KO(neo)] (37). To rescue the AML1-deficient ES cell phenotype, we designed a replacement-type vector (knock-in vector) which creates an artificial allele [KI(puro)] that expresses the PEBP2αB1 isoform of the AML1 protein in place of the disrupted exon 4 by means of homologous recombination. Clones which had undergone targeted insertion at either of the hygromycin or neomycin alleles were detected by Southern blot analyses with a 5′ outside probe (B) and 3′ outside probe (C), in which the knock-in alleles were detectable as XbaI-restricted fragments of ca. 11 and 7 kb, respectively. Abbreviations: hygr, hygromycin B resistance cassette; neo, neomycin resistance cassette; puro, puromycin resistance cassette; DT-A, diphtheria toxin-A suicide cassette. Arrows above selection cassettes indicate the orientation of the transcription. (D) Expression of the AML1 message in the knock-in ES clones was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis, which amplified the 292-bp fragment of the cDNA with a primer pair corresponding to exons 3 and 4 of the gene locus (top panel). Parallel amplification for the HPRT gene (bottom panel) demonstrates the integrity of the RNA samples obtained from the undifferentiated ES cell clones.

Reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR analysis for expression of the AML1 gene.

Total RNA was isolated from undifferentiated ES cells or embryoid bodies (EBs), and cDNA was subsequently synthesized with random hexamers as described elsewhere (35). A part of the AML1 messages was amplified by PCR with a pair of oligonucleotide primers which bracketed the targeted site within the Runt domain and corresponded to the respective sequences in exons 3 and 4 (37). Parallel reactions were performed with hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase primers (15) to ensure the integrity of the RNA samples. Amplified PCR products were size fractionated by electrophoresis through an agarose gel and detected on a UV transilluminator after staining with ethidium bromide.

Western blot analysis for expressed AML1 proteins.

Cells were lysed in boiling radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, electrophoretically separated on a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Proteins were detected with an AML1 N-terminal peptide (34) or the monoclonal antibody against HA peptide (BAbCO, Berkeley, Calif.) with ECL detection substrate (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) as described previously (34).

In vitro differentiation of EBs.

The procedure for the in vitro differentiation of EBs was based on a previously described method (15, 54), with some modifications (37). In brief, ES cells were adapted to grow without a feeder cell layer. Triplicated cell suspensions of 3 × 102 adapted ES cells were plated in 1-ml mixtures of 1.2% methylcellulose in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium containing 15% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, and 450 μM monothioglycerol. The cultures were supplemented with 2 U of human erythropoietin per ml and 50 ng of human G-CSF (both purchased from Kirin Brewery Co., Tokyo, Japan) per ml and 10 ng of murine GM-CSF per ml, 20 ng of murine stem cell factor per ml, and 5 ng of murine interleukin-3 (IL-3) (all from R & D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) per ml for hematopoietic differentiation of EBs, which were scored by visual examination with an inverted microscope for the presence of primitive erythrocytes on day 9 and of surrounding macrophages on day 14. The presence of individual hematopoietic cell lineages was confirmed by microscopic examination of cytocentrifuge preparations of single EBs.

Second-step in vitro cultures for hematopoietic progenitors.

Second-step cultures for hematopoietic progenitors were performed according to the methods described by Keller et al. (15). EBs, which were grown under the culture conditions described earlier (supplemented with 20 ng of murine stem cell factor per ml), were recovered on day 6 of culture for the examination of erythroid precursors of primitive origin and on day 10 for that of hematopoietic progenitors of definitive origin. The EBs were disrupted by collagenase treatment, and 105 recovered single cells were then recultured in triplicate in 1-ml mixtures of Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium containing 1.2% methylcellulose, 30% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Cultures for the replated primitive erythroid colonies were supplemented with 2 U of human erythropoietin per ml, and cultures for definitive progenitors were supplemented with the same combination of CSF as described for the EB cultures above (see Fig. 3A). Colonies were scored by visual examination with an inverted microscope on days 4 and 12 for primitive erythroid progenitors (Ery-P) and colonies of definitive origin, respectively. The hematopoietic lineages of the colonies were confirmed by microscopical examination of the May-Gruenwald-Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations.

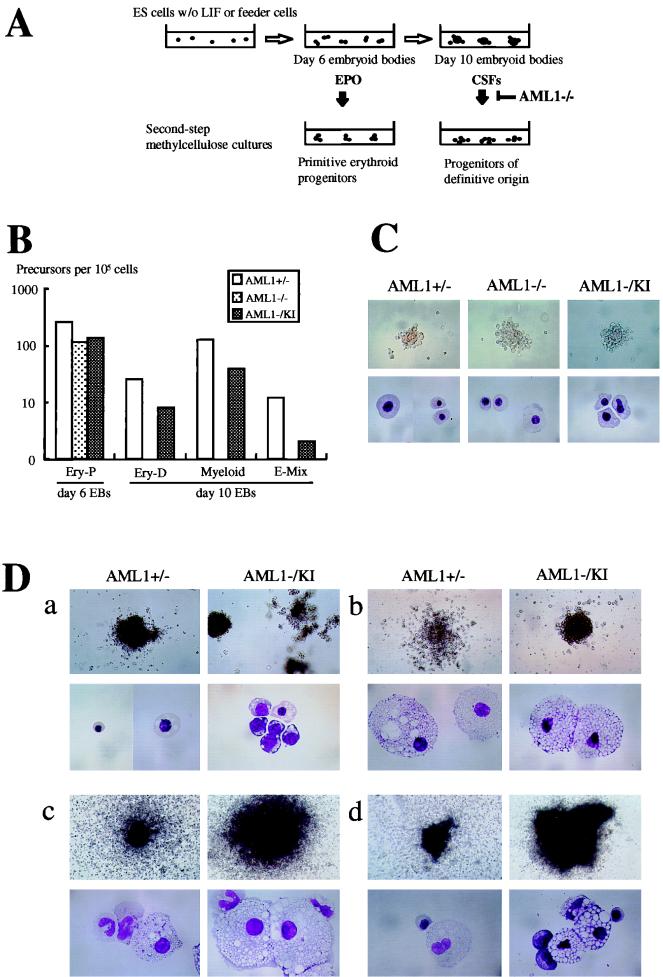

FIG. 3.

Results of the two-step differentiation experiments of the knock-in clones. (A) Schematic representation of the method used in the present study to induce the hematopoietic differentiation of ES cells. When ES cells are cultured to form EBs in semisolid media without feeder cells or leukemia inhibitory factor, they develop hematopoietic cells of primitive and definitive origins, which are detectable by second-step cultures in the presence of appropriate CSF. In contrast, when AML1−/− ES cells were subjected to this analysis, they failed to develop hematopoietic cells of definitive origin. (B) In vitro differentiation of ES cell clones of each of the AML1 genotypes into hematopoietic precursors in a representative experiment. Colonies of Ery-P, definitive erythroid (Ery-D), and granulocyte-macrophage and macrophage (Myeloid), as well as mixed lineages including definitive erythroid (E-Mix), were scored in a two-step replating assay. ES cells were cultured to form EBs and then disrupted on day 6 for Ery-P and on day 10 for definitive precursors, after which 105 cells were subjected to second-step cultures with appropriate CSF (see Materials and Methods). Open bars, grey bars, and dark bars represent AML1+/−, AML1−/−, and AML1−/− with knock-in clones, respectively. (C) Representative colonies of the primitive erythroid lineage observed in the two-step replating assay with EBs on day 6 of culture. The morphology of the colonies in situ (top panels) and of composing primitive erythroid cells stained with May-Gruenwald-Giemsa staining (lower panels) was almost identical among the clones. Magnifications: top panels, ×50; bottom panels, ×330. (D) Representative hematopoietic colonies of definitive origin observed in the second-step cultures of day 10 EBs derived from AML1+/− and knock-in clones. As shown, the appearance of the colonies and the morphology of the composing cells of definitive erythroid (a), macrophage (b), granulocyte-macrophage (c), and mixed lineages including definitive erythroid (d) of the rescued knock-in clones (AML1−/KI) were indistinguishable from those observed in the cultures of the control heterozygous clones (AML1+/−). Magnifications: upper panels of a, ×50; upper panels of b to d, ×20; lower panels, ×198.

Chimeric mice production.

The generation of chimeric mice was essentially as previously described (49). In brief, ES cell clones of normal ploidy and with a single vector insertion were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts. Manipulated blastocysts were then transferred into the uterines of pseudopregnant mother mice, and the chimerism of the subsequently born mice was evaluated on the basis of the coat color.

GPI isoenzyme analysis.

Glucose phosphate isomerase (GPI) isoenzyme analysis was performed as described elsewhere (37). Briefly, frozen tissue samples were homogenized in 50 mM Tris-HCl containing 0.1% Triton X-100, and aliquots of the appropriately diluted supernatant were subjected to electrophoretical fractionation on cellulose acetate membranes (Helena Laboratories, Beaumont, Tex.). The bands of the enzyme were visualized by treating the membranes with a 10-ml mixture of 0.9% agarose containing 5 mM magnesium acetate, 15 mg of fructose-6-phosphate, 2 mg of methylthiazolium tetrazolium, 0.36 mg of phenazine methosulfate, 2 mg of NADP, and 10 U of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (all from Sigma) for 10 to 15 min.

RESULTS

Creating a knock-in allele which expresses PEBP2αB1 (AML1b) cDNA in AML1-deficient ES cells.

AML1 is known to be expressed in a cell-lineage-specific and developmental-stage-specific manner in hematopoietic cells (17, 28, 43, 45). Interestingly, an analysis of AML1's own transcriptional regulatory sequences revealed multiple AML1-binding sites in both its proximal and distal promoters, suggesting that its actual transcription may be autoregulated (8). Consistent with this interpretation, our preliminary attempts to rescue the AML1-deficient phenotype by expressing PEBP2αB1 (murine AML1b) from a ubiquitous promoter, the cis element of the mouse phosphoglycerate kinase 1 gene, failed (not shown). In order to overcome the inability of ubiquitously expressed AML1 to rescue the phenotype, we chose to use a knock-in approach that would achieve the expression of the exogenous gene from the endogenous AML1 regulatory elements. We designed a replacement-type vector which created an artificial exon 4 that generates a full-length transcript for the PEBP2αB1 (AML1b) isoform of the murine AML1 protein, followed by a polyadenylation signal and puromycin resistance cassette (Fig. 1; see Materials and Methods). We examined 110 single AML1−/− ES cell clones which became resistant to puromycin after electroporation of the linearized replacement vector, pRES-AML1b, by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1B and C) and found that the homologous recombination of the vector had occurred within the hygromycin allele in 28 single-cell clones and at the neomycin allele in 21 single-cell clones (45% targeting efficiency). Expression of the AML1b gene from the resultant knock-in allele was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis with primers corresponding to the genomic sequence for AML1 exons 3 and 4. As shown in Fig. 1D, the mRNA for the knocked-in PEBP2αB1 gene was expressed in all knock-in clones regardless of which allele was targeted.

Knock-in clones restore the ability of ES cells to undergo hematopoietic differentiation of definitive origin in vitro.

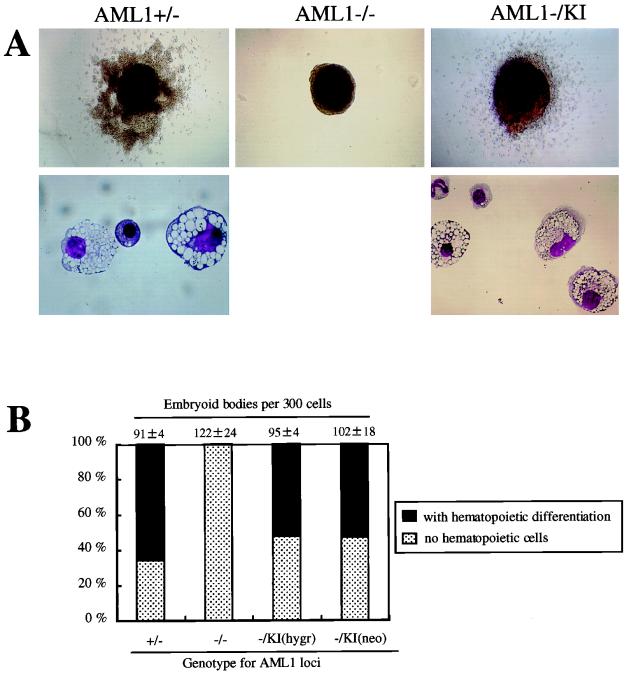

To determine if the knock-in AML1 allele could restore the ability of these ES cell clones to differentiate into hematopoietic cells of definitive origin, the clones were assessed by an in vitro differentiation assay system. As reported by us and others, homozygous mice deficient in AML1 die in midgestation as a result of a complete block in definitive fetal liver-derived hematopoiesis, thus pointing to a pivotal role for AML1 in the establishment of definitive hematopoiesis (37, 51). This in vivo phenotype can be replicated in vitro by the ES cell system (37). When AML1+/+ or AML1+/− ES cells were cultured in semisolid media without leukemia inhibitory factor, they formed EBs, which consisted of tight cell aggregates that contained all three germ cell layers (15, 54). The AML1+/− clone-derived EBs developed primitive erythrocytes inside them after 8 to 10 days in culture as well as surrounding definitive macrophages (Fig. 2A, upper left panel) by 12 to 14 days (15, 54). Microscopic examination of the cytospin preparations showed that most of the hematopoietic cells within these EBs were mature macrophages, while a few erythroid and granulocytic cells were also observed (Fig. 2A, lower left panel). EBs derived from AML1−/− clones, in contrast, failed to develop any definitive hematopoietic cells (Fig. 2A, center panel), thus replicating the AML1-deficient phenotype in vitro. When knock-in ES clones (AML1−/K1) were examined, cultured EBs were surrounded by macrophages and were similar in appearance to those formed with wild-type or AML1+/− cells, as expected (five clones examined, representative results are shown) (Fig. 2A, upper right panel). Cytospin preparations of these EBs demonstrated the cells to be mostly macrophages with occasional granulocytes and erythrocytes (Fig. 2A, lower right panel). The morphology of the cells derived from the knock-in clones was indistinguishable from that of cells developed from control AML1+/+ or AML1+/− clones. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 2B, the plating efficiencies and the incidence of visible macrophage differentiation within EBs of AML1+/− and knock-in clones were similar. In addition, knock-in clones with a targeted insertion of the cDNA either at the hygromycin allele (three clones analyzed) or the neomycin allele (two clones analyzed) showed a similar capability of hematopoietic differentiation (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Results of the EB differentiation experiments of knock-in clones. (A) Appearance of the representative day 14 EBs derived from the ES cell clones of AML1+/− and AML1−/− and knock-in with wild-type AML1b (AML1−/KI) genotypes. AML1+/− ES cell clones formed EBs, the majority of which was surrounded by hematopoietic cells (upper left panel) consisting primarily of mature macrophages and a few erythroid and granulocytic cells (lower left panel). EBs derived from AML1−/− clones developed no such cells (center). In contrast, knock-in ES clones (AML1−/KI) formed hematopoietic cells around the EBs (upper right panel), consisting of macrophages with occasional granulocytes and erythrocytes (lower right panel). The morphology of the cells derived from the knock-in clones was indistinguishable from that of cells developed from control AML1+/− clones. Original magnifications: upper panels ×20, lower panels, ×132. (B) Incidence of hematopoietic differentiation of the day 14 EBs derived from ES cell clones of AML1+/−, AML1−/−, AML1−/− with a knock-in AML1b at the hygromycin allele [AML1−/KI(hygr)], and AML1−/− with a knock-in AML1b for the neomycin allele [AML1−/KI(neo)] genotypes in a representative experiment. Dark bars indicate the percentage of the EBs with visible hematopoietic cells whereas light bars represent those without a hematopoietic element. Actual numbers of the EBs grown per 300 ES cells are given above each bar as the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate cultures.

We then used a two-step culture system to analyze the frequency of individual progenitors developing within EBs. To assess Ery-P, day 6 EBs were disrupted and recultured in the presence of erythropoietin, as schematically outlined in Fig. 3A. As shown in Fig. 3B, comparable numbers of Ery-P were detected in all analyzed clones, including AML1+/−, AML1−/−, and AML1−/KI, with representative colonies shown in Fig. 3C. As expected, no definitive progenitors were detected in day 10 EBs derived from AML1-deficient ES cell clones (Fig. 3B). In contrast, hematopoietic progenitors of definitive origin were identified in EBs derived from ES cells containing the knock-in allele (Fig. 3B). Moreover, both the number of colonies (Fig. 3B) and the morphology of the cells of the developing colonies (Fig. 3D) of AML1+/− and knock-in clones were similar although there was a tendency for the formation of fewer colonies in cultures from the knock-in EBs. Thus, the expression of the PEBP2αB1 (AML1b) isoform through a knock-in strategy restored the ability of the AML1-deficient ES cells to differentiate into hematopoietic lineages in vitro.

Knock-in clones can contribute to both myeloid and lymphoid tissues in vivo.

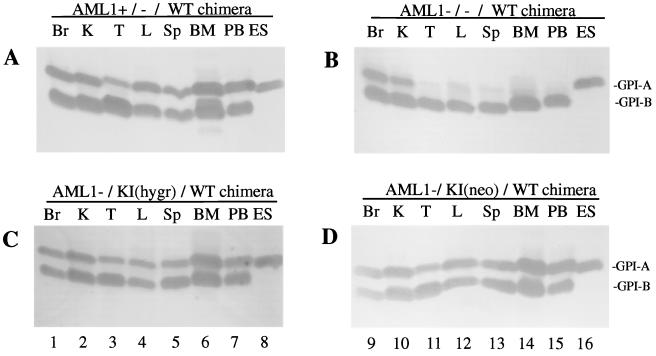

To determine whether the knock-in clones have the capacity to differentiate into hematopoietic lineages in vivo, these ES cells were injected into blastocysts and the resultant chimeric mice were analyzed for the contribution of the ES cells to hematopoietic tissues. The relative contribution of AML1+/−, AML1−/−, and AML1−/KI cells to the chimeric animals, as estimated by an agouti coat color, was similar and typically ranged from 30 to 50%. The extent of contribution of the injected ES cells to individual organs was determined by means of GPI isoform analysis (37). The E14 ES cells contain the GPI-A isoform, whereas the C57BL/6 of the host strain are GPI-B isoform specific. We examined 11 different tissues from 1-month-old chimeric mice, and representative results are illustrated in Fig. 4. As described previously (37), AML1−/− ES cells failed to contribute to hematopoietic tissues, whereas they made significant contributions to nonhematopoietic tissues. In contrast, the knock-in clones, regardless of which allele underwent a targeted insertion of the cDNA, made a major contribution to all tissues, including sites of lymphohematopoiesis, i.e., peripheral blood, bone marrow, spleen, and thymus. These results clearly indicate that the expression of the AML1b (PEBP2αB1) isoform from the knock-in allele is sufficient to enable the AML1-deficient ES cells to develop into lymphoid and myeloid-erythroid lineages within the context of the animal.

FIG. 4.

Contribution of AML1−/−, AML1+/−, and AML1−/KI ES cells to tissues in chimeric mice. Representative results for the GPI analysis of chimeric mice derived from AML1+/− (A) and AML1−/− (B) and knock-in clones for the hygromycin allele [AMLl−/KI(hygr)] (C) and neomycin allele [AML1−/KI(neo)] (D). ES cells contain the GPI-A isoform as indicated in lanes 8 and 16, whereas the host contains the GPI-B isoform. Results from the following tissues are shown: brain (Br), kidney (K), thymus (T), liver (L), spleen (Sp), bone marrow (BM), and peripheral blood (PB), and ES cells (ES) were controls. WT, wild type.

Hematopoietic rescue depends on the transactivation domain of the PEBP2αB1 (AML1b), but not on the C-terminus, including the VWRPY motif.

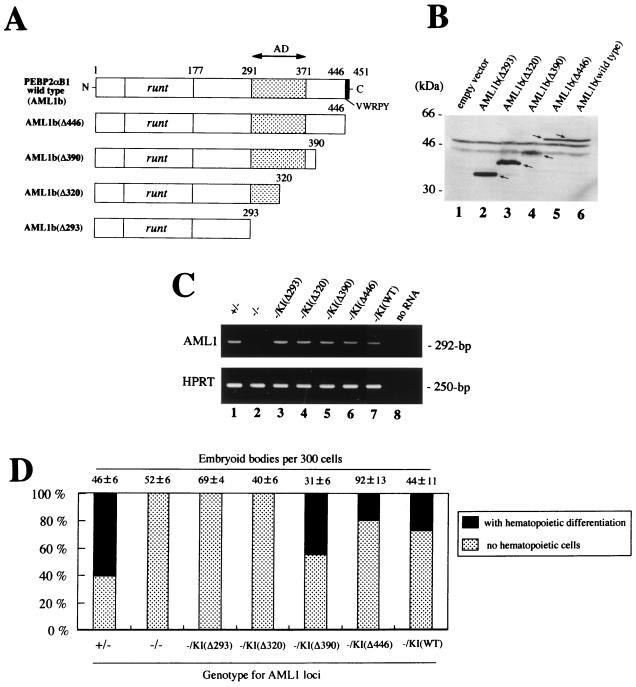

As an initial attempt to dissect the subdomains of the AML1 molecule required for its biological role in hematopoietic development, we expressed a series of C-terminal deletion mutants of PEBP2αB1 (AML1b) in AML1−/− ES cells by using the knock-in approach (see Materials and Methods). In each transfection, 20 to 38% of the puromycin-resistant clones underwent homologous recombination at either allele, and two to six clones for each of the knock-in constructs, whose expression was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 5C), were assessed for hematopoietic differentiation, and representative results are illustrated in Fig. 5. When the AML1bΔ446 mutant, which lacks the five most C-terminal amino acids of the VWRPY motif, was expressed, the AML1-deficient ES cell clones showed a restored ability to differentiate into definitive hematopoietic lineages (Fig. 5D). Similarly, the clones with a knock-in allele for the AML1bΔ390 mutant, which lacks the 61 C-terminal amino acid residues, retained the ability to rescue the AML1-deficient phenotype. The phenotype was reproducible when the procedure was repeated with multiple clones regardless of which allele was targeted. The morphology of the hematopoietic cells that developed from these clones was similar to those observed in AML1+/− clones (not shown). In contrast, AML1bΔ320 and AML1bΔ293 failed to rescue the hematopoietic defect (Fig. 5D). Thus, the in vitro rescue assay revealed that the 390 N-terminal amino acid residues of AML1b (451 full-length residues) are sufficient to maintain its biological activity in definitive hematopoiesis. By contrast, the 61 C-terminal residues, including the VWRPY motif at the terminus, were not required for this function.

FIG. 5.

Biological properties of the C-terminal deletion mutants of AML1b. (A) Schematic representation of the module structure according to Kanno et al. (14) of the wild-type PEBP2αB1 (AML1b) and each mutant analyzed. (B) The integrity of the mutant constructs was confirmed by Western blot analysis of transiently transfected COS-7 cells. (C) Expression of the exogenous genes in ES cells were confirmed by RT-PCR analysis with primers from exons 3 and 4 (see the legend for Fig. 1D). (D) Hematopoietic differentiation of AML1−/− ES knock-in clones expressing the different AML1b mutants in a representative experiment. Dark bars indicate the percentage of the EBs with visible hematopoietic cells whereas light bars represent those without a hematopoietic element. Actual numbers of the EBs grown per 300 ES cells are given above each bar as the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate cultures.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we established an in vitro ES cell experimental system that replicates the hematopoietic defect resulting from the loss of AML1. Using this system, we demonstrated that the hematopoietic defect can be rescued by expressing a PEBP2αB1 (AML1b) isoform under the control of the endogenous AML1-regulatory sequences through a knock-in approach. The ES cell clones containing the AML1 knock-in allele showed a restored ability to differentiate into all lineages of definitive hematopoiesis. These results provide direct evidence that the hematopoietic phenotype found in AML1-deficient mice is due solely to the lack of this gene, thus excluding any possibility that the phenotype of the mice might have been influenced by so-called positional artifacts (38). Importantly, the knock-in clones could participate in lymphohematopoiesis in vivo as demonstrated in the chimera mouse analysis, thus suggesting that the behavior observed in the in vitro ES cell experimental system should correspond to their behavior within the context of an intact animal.

We successfully adopted a knock-in strategy to rescue the AML1-deficient phenotype in the present study. The experimental strategy that we used targeted AML1 exon 4, thus resulting in the generation of an artificial allele that retained the ability to be alternatively spliced to produce AML1b, AML1c, and AML1ΔN (17, 28, 56). These AML1 isoforms contain the presumably full-length C terminus, including the conserved VWRPY motif at the end, and are differentially produced by alternative splicing in their 5′ sequences upstream to exon 4 (17, 28, 56). Therefore, our results do not directly assess differences in the biological activities of these isoforms. However, our results demonstrate that the AML1 isoform(s) which has the longer C terminus is responsible for the biological activity of this gene and that the isoform(s) which lacks the C terminus, such as that encoded by AML1a (29), is not required for stem cells to undergo hematopoietic differentiation into definitive lineages. Consistent with these observations, Northern blot analyses revealed that AML1b and AML1c, which encode polypeptides of 453 and 480 amino acid residues, respectively, are the most common forms expressed in hematopoietic cells in humans in contrast to the minor amount of the AML1a message (28). Furthermore, by mobility shift assay analysis with AML1-binding oligonucleotide probes and specific antibodies raised to the AML1 protein, it has been reported that only a full-length AML1 protein was consistently detected in a panel of hematopoietic cell lines (25). While AML1b and AML1c isoforms have been shown to activate transcription in reporter gene assays with cis elements of putative target genes, including the M-CSF receptor, GM-CSF, and T-cell antigen receptor genes (1, 24, 50), the AML1a isoform, which contains 250 residues and lacks most of the carboxyl terminus downstream from the Runt domain, lacks the ability to activate transcription although it retains the ability to bind to CBF sites and to associate with CBFβ (1, 12, 23). Therefore, AML1a is believed to interfere, in a dominant manner, with normal AML1 (or CBF/PEBP2) activity (50), and thus regulation of alternative splicing has been proposed to function in the modulation of the biological activity of AML1. It will be of interest to define the biological role, if any, of the AML1a isoform in later stages of hematopoiesis or in other nonhematopoietic cell lineages through the production of genetically engineered mice that homozygously carry the knock-in AML1b allele in their germ line.

Conventional biochemical studies suggest that the transactivation domain of AML1 resides within its C-terminal portion (1, 24, 50). Specifically, a classic transactivating domain is localized to the region between residues 291 and 371, whereas a transcription repression domain is located between 371 and 411 (Fig. 5A) (14). In addition, the C-terminal VWRPY motif (Fig. 5A) was conserved throughout evolution among all known AML1-related molecules and is believed to mediate binding to the transcriptional corepressor Groucho/transducin-like enhancer of split (10, 11, 18), but deletion of this region has little effect on transcriptional activation (14). We used the AML1-deficient ES cell rescue system to dissect the functional domains in the C-terminal region. Our results indicate that the transcription activation domain is required for AML1's role in early hematopoiesis. By contrast, the C-terminal region of the protein appears to be dispensable for this biological function. Thus, the biological significance of the conserved C-terminal VWRPY motif remains to be clarified.

In summary, our data demonstrate a critical role for AML1-mediated transcriptional activation in establishing definitive hematopoiesis. These findings, together with the experimental system established in the present study, should contribute to further clarification of the molecular mechanisms of normal and leukemic hematopoiesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shuji Takao, Katsuya Ashida, Yoshio Yanase, and Nobuhisa Onoda for excellent technical assistance. We are also grateful to Tomoko Asada for secretarial assistance in preparing figures.

This work was supported by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, Japan; by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Japan; by The Kowa Life Science Foundation; by The Shimizu Foundation for the Promotion of Immunology Research; by The Naito Foundation; by grants from CREST of Japan Science and Technology Corporation; by National Institute of Health (NIH) grant P01 CA71907-03; by NIH Cancer Center CORE grant CA-21765; and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bae S-C, Ogawa E, Maruyama M, Oka H, Satake M, Shigesada K, Jenkins N A, Gilbert D J, Copeland N G, Ito Y. PEBP2αB/mouse AML1 consists of multiple isoforms that possess differential transactivation potentials. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3242–3252. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae S C, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Ogawa E, Maruyama M, Inuzuka M, Kagoshima H, Shigesada K, Satake M, Ito Y. Isolation of PEBP2 alpha B cDNA representing the mouse homolog of human acute myeloid leukemia gene, AML1. Oncogene. 1993;8:809–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daga A, Tighe J E, Calabi F. Leukaemia/Drosophila homology. Nature. 1992;356:484. doi: 10.1038/356484b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downing J R. The AML1-ETO chimaeric transcription factor in acute myeloid leukaemia: biology and clinical significance. Br J Haematol. 1999;106:296–308. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dzierzak E, Medvinsky A. Mouse embryonic hematopoiesis. Trends Genet. 1995;11:359–366. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erickson P, Gao J, Chang K S, Look T, Whisenant E, Raimondi S, Lasher R, Trujillo J, Rowley J, Drabkin H. Identification of breakpoints in t(8;21) acute myelogenous leukemia and isolation of a fusion transcript, AML1/ETO, with similarity to Drosophila segmentation gene, runt. Blood. 1992;80:1825–1831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gamou T, Kitamura E, Hosoda F, Shimizu K, Shinohara K, Hayashi Y, Nagase T, Yokoyama Y, Ohki M. The partner gene of AML1 in t(16;21) myeloid malignancies is a novel member of the MTG8(ETO) family. Blood. 1998;91:4028–4037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghozi M C, Bernstein Y, Negreanu V, Levanon D, Groner Y. Expression of the human acute myeloid leukemia gene AML1 is regulated by two promoter regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1935–1940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golub T R, Barker G F, Lovett M, Gilliland D G. Fusion of PDGF receptor beta to a novel ets-like gene, tel, in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with t(5;12) chromosomal translocation. Cell. 1994;77:307–316. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imai Y, Kurokawa M, Tanaka K, Friedman A D, Ogawa S, Mitani K, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. TLE, the human homolog of groucho, interacts with AML1 and acts as a repressor of AML1-induced transactivation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252:582–589. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jimenez G, Pinchin S M, Ish-Horowicz D. In vivo interactions of the Drosophila Hairy and Runt transcriptional repressors with target promoters. EMBO J. 1996;15:7088–7098. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kagoshima H, Shigesada K, Satake M, Ito Y, Miyoshi H, Ohki M, Pepling M, Gergen P. The Runt domain identifies a new family of heteromeric transcriptional regulators. Trends Genet. 1993;9:338–341. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90026-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kania M A, Bonner A S, Duffy J B, Gergen J P. The Drosophila segmentation gene runt encodes a novel nuclear regulatory protein that is also expressed in the developing nervous system. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1701–1713. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanno T, Kanno Y, Chen L F, Ogawa E, Kim W Y, Ito Y. Intrinsic transcriptional activation-inhibition domains of the polyomavirus enhancer binding protein 2/core binding factor alpha subunit revealed in the presence of the beta subunit. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2444–2454. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller G, Kennedy M, Papayannopoulou T, Wiles M V. Hematopoietic commitment during embryonic stem cell differentiation in culture. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:473–486. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenny N, Westendorf J J, Hiebert S W. Transcriptional regulation during myelopoiesis. Mol Biol Rep. 1997;24:157–168. doi: 10.1023/a:1006859700409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levanon D, Bernstein Y, Negreanu V, Ghozi M C, Bar-Am I, Aloya R, Goldenberg D, Lotem J, Groner Y. A large variety of alternatively spliced and differentially expressed mRNAs are encoded by the human acute myeloid leukemia gene AML1. DNA Cell Biol. 1996;15:175–185. doi: 10.1089/dna.1996.15.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levanon D, Goldstein R E, Bernstein Y, Tang H, Goldenberg D, Stifani S, Paroush Z, Groner Y. Transcriptional repression by AML1 and LEF-1 is mediated by the TLE/Groucho corepressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11590–11595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu P, Tarle S A, Hajra A, Claxton D F, Marlton P, Freedman M, Siciliano M J, Collins F S. Fusion between transcription factor CBF beta/PEBP2 beta and a myosin heavy chain in acute myeloid leukemia. Science. 1993;261:1041–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.8351518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Look A T. Oncogenic transcription factors in the human acute leukemias. Science. 1997;278:1059–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopata M A, Cleveland D W, Sollner-Webb B. High level transient expression of a chloramphenicol acetyl transferase gene by DEAE-dextran mediated DNA transfection coupled with a dimethyl sulfoxide or glycerol shock treatment. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:5707–5717. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.14.5707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medvinsky A, Dzierzak E. Definitive hematopoiesis is autonomously initiated by the AGM region. Cell. 1996;86:897–906. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyers S, Downing J R, Hiebert S W. Identification of AML-1 and the (8;21) translocation protein (AML-1/ETO) as sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins: the runt homology domain is required for DNA binding and protein-protein interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6336–6345. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyers S, Lenny N, Hiebert S W. The t(8;21) fusion protein interferes with AML-1B-dependent transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1974–1982. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers S, Lenny N, Sun W, Hiebert S W. AML-2 is a potential target for transcriptional regulation by the t(8;21) and t(12;21) fusion proteins in acute leukemia. Oncogene. 1996;13:303–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitani K, Ogawa S, Tanaka T, Miyoshi H, Kurokawa M, Mano H, Yazaki Y, Ohki M, Hirai H. Generation of the AML1-EVI-1 fusion gene in the t(3;21)(q26;q22) causes blastic crisis in chronic myelocytic leukemia. EMBO J. 1994;13:504–510. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyoshi H, Kozu T, Shimizu K, Enomoto K, Maseki N, Kaneko Y, Kamada N, Ohki M. The t(8;21) translocation in acute myeloid leukemia results in production of an AML1-MTG8 fusion transcript. EMBO J. 1993;12:2715–2721. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyoshi H, Ohira M, Shimizu K, Mitani K, Hirai H, Imai T, Yokoyama K, Soeda E, Ohki M. Alternative splicing and genomic structure of the AML1 gene involved in acute myeloid leukemia. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2762–2769. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.14.2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyoshi H, Shimizu K, Kozu T, Maseki N, Kaneko Y, Ohki M. t(8;21) breakpoints on chromosome 21 in acute myeloid leukemia are clustered within a limited region of a single gene, AML1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10431–10434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niki M, Okada H, Takano H, Kuno J, Tani K, Hibino H, Asano S, Ito Y, Satake M, Noda T. Hematopoiesis in the fetal liver is impaired by targeted mutagenesis of a gene encoding a non-DNA binding subunit of the transcription factor, polyomavirus enhancer binding protein 2/core binding factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5697–5702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nucifora G, Begy C R, Kobayashi H, Roulston D, Claxton D, Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Parganas E, Ihle J N, Rowley J D. Consistent intergenic splicing and production of multiple transcripts between AML1 at 21q22 and unrelated genes at 3q26 in (3;21)(q26;q22) translocations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4004–4008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogawa E, Inuzuka M, Maruyama M, Satake M, Naito-Fujimoto M, Ito Y, Shigesada K. Molecular cloning and characterization of PEBP2 beta, the heterodimeric partner of a novel Drosophila runt-related DNA binding protein PEBP2 alpha. Virology. 1993;194:314–331. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogawa E, Maruyama M, Kagoshima H, Inuzuka M, Lu J, Satake M, Shigesada K, Ito Y. PEBP2/PEA2 represents a family of transcription factors homologous to the products of the Drosophila runt gene and the human AML1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6859–6863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okuda T, Cai Z, Yang S, Lenny N, Lyu C J, van Deursen J M, Harada H, Downing J R. Expression of a knocked-in AML1-ETO leukemia gene inhibits the establishment of normal definitive hematopoiesis and directly generates dysplastic hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 1998;91:3134–3143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okuda T, Cleveland J L, Downing J R. PCTAIRE-1 and PCTAIRE-3, two members of a novel cdc2/CDC28-related protein kinase gene family. Oncogene. 1992;7:2249–2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okuda T, Shurtleff S A, Valentine M B, Raimondi S C, Head D R, Behm F, Curcio-Brint A M, Liu Q, Pui C H, Sherr C J, Beach D, Look A T, Downing J R. Frequent deletion of p16INK4a/MTS1 and p15INK4b/MTS2 in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1995;85:2321–2330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okuda T, van Deursen J, Hiebert S W, Grosveld G, Downing J R. AML1, the target of multiple chromosomal translocations in human leukemia, is essential for normal fetal liver hematopoiesis. Cell. 1996;84:321–330. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olson E N, Arnold H H, Rigby P W, Wold B J. Know your neighbors: three phenotypes in null mutants of the myogenic bHLH gene MRF4. Cell. 1996;85:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osato M, Asou N, Abdalla E, Hoshino K, Yamasaki H, Okubo T, Suzushima H, Takatsuki K, Kanno T, Shigesada K, Ito Y. Biallelic and heterozygous point mutations in the runt domain of the AML1/PEBP2alphaB gene associated with myeloblastic leukemias. Blood. 1999;93:1817–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romana S P, Mauchauffe M, Le Coniat M, Chumakov I, Le Paslier D, Berger R, Bernard O A. The t(12;21) of acute lymphoblastic leukemia results in a tel-AML1 gene fusion. Blood. 1995;85:3662–3670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roulston D, Espinosa R, 3rd, Nucifora G, Larson R A, Le Beau M M, Rowley J D. CBFA2 (AML1) translocations with novel partner chromosomes in myeloid leukemias: association with prior therapy. Blood. 1998;92:2879–2885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sasaki K, Yagi H, Bronson R T, Tominaga K, Matsunashi T, Deguchi K, Tani Y, Kishimoto T, Komori T. Absence of fetal liver hematopoiesis in mice deficient in transcriptional coactivator core binding factor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12359–12363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satake M, Nomura S, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Takahama Y, Hashimoto Y, Niki M, Kitamura Y, Ito Y. Expression of the Runt domain-encoding PEBP2α genes in T cells during thymic development. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1662–1670. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shivdasani R A, Orkin S H. The transcriptional control of hematopoiesis. Blood. 1996;87:4025–4039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simeone A, Daga A, Calabi F. Expression of runt in the mouse embryo. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:61–70. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Speck N A, Stacy T, Wang Q, North T, Gu T L, Miller J, Binder M, Marin-Padilla M. Core-binding factor: a central player in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Cancer Res. 1999;59(Suppl):1789S–1793S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Speck N A, Terryl S. A new transcription factor family associated with human leukemias. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1995;5:337–364. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v5.i3-4.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sussman D J, Milman G. Short-term, high-efficiency expression of transfected DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:1641–1643. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.8.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takeda K, Tsutsui H, Yoshimoto T, Adachi O, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Okamura H, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Defective NK cell activity and Th1 response in IL-18-deficient mice. Immunity. 1998;8:383–390. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanaka T, Tanaka K, Ogawa S, Kurokawa M, Mitani K, Nishida J, Shibata Y, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. An acute myeloid leukemia gene, AML1, regulates hemopoietic myeloid cell differentiation and transcriptional activation antagonistically by two alternative spliced forms. EMBO J. 1995;14:341–350. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Q, Stacy T, Binder M, Marin-Padilla M, Sharpe A H, Speck N A. Disruption of the Cbfa2 gene causes necrosis and hemorrhaging in the central nervous system and blocks definitive hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3444–3449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Q, Stacy T, Miller J D, Lewis A F, Gu T L, Huang X, Bushweller J H, Bories J C, Alt F W, Ryan G, Liu P P, Wynshaw-Boris A, Binder M, Marin-Padilla M, Sharpe A H, Speck N A. The CBFbeta subunit is essential for CBFalpha2 (AML1) function in vivo. Cell. 1996;87:697–708. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang S, Wang Q, Crute B E, Melnikova I N, Keller S R, Speck N A. Cloning and characterization of subunits of the T-cell receptor and murine leukemia virus enhancer core-binding factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3324–3339. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiles M V, Keller G. Multiple hematopoietic lineages develop from embryonic stem (ES) cells in culture. Development. 1991;111:259–267. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yergeau D A, Hetherington C J, Wang Q, Zhang P, Sharpe A H, Binder M, Marin-Padilla M, Tenen D G, Speck N A, Zhang D E. Embryonic lethality and impairment of haematopoiesis in mice heterozygous for an AML1-ETO fusion gene. Nat Genet. 1997;15:303–306. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Y-W, Bae S-C, Huang G, Fu Y-X, Lu J, Ahn M-Y, Kanno Y, Kanno T, Ito Y. A novel transcript encoding an N-terminally truncated AML1/PEBP2αB protein interferes with transactivation and blocks granulocytic differentiation of 32Dcl3 myeloid cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4133–4145. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]