Abstract

Background

Gallbladder cancer is generally rare but can be more common in some populations. The aim of this study was to present an analysis of gallbladder cancer epidemiology in Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective study of gallbladder cancer cases in Saudi Arabia from 2004 to 2015 was conducted. The gallbladder cancer data were accessed through the Saudi Cancer Registry (SCR) reports for 13 administrative regions. The number of gallbladder cancer cases with percentage, the crude incidence rate (CIR) and the age-standardised incidence rate (ASIR), stratified by regions, gender, and the years of diagnoses were analysed.

Results

A total of 1678 gallbladder cancer cases, 702 in males and 976 in females, were registered between 2004 and 2015. Saudi women and men in the 75 and above age-group were found to have the highest diagnosis rate of gallbladder cancer. In males, the overall ASIR among Saudi males was 1.1 per 100,000 (95% CI, 0.9 to 1.2). The Eastern region had the highest overall ASIR at 1.5 per 100,000 males, followed by Tabuk and Riyadh at 1.4 and 1.3 higher than other regions (F(12,143)=1.930, P<0.001). The overall ASIR among Saudi females was 1.6 per 100,000 (95% CI, 1.4 to 1.7). Riyadh had the highest overall ASIR at 2.4 per 100,000 females, followed by the Eastern region, and Qassim at 1.9 and 1.5, respectively, all higher than other provinces of the country (F(12,143)=2.496, P<0.005). The ASIR and CIR were lower among males than females (ratio 0.7).

Conclusion

Gallbladder cancer incidence is relatively low in Saudi Arabia. The rates were higher in females than males. ASIR showed variations between different provinces of Saudi Arabia. In females, the highest ASIR was in Riyadh. In males, ASIR was highest in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia.

Keywords: gallbladder neoplasms, epidemiology, incidence, Middle East, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

While gallbladder cancer (GBC) is the most common malignancy affecting the gallbladder, it is generally rare in most populations with a global rate of around 1.3% of total cancers.1,2 However, in some regions of the world, GBC is much more widespread, such as in regions of Chile where rates can be as high as 27/100,000 in women and regions of northern India where rates reach 21.5/100,000.1 Alongside high incidence in parts of South America, India, and Pakistan, high rates are also found in East Asia and Eastern Europe.3

GBC is an aggressive disease with a high rate of metastasis, this combined with a lack of symptoms in the early stages and its general rarity result in high mortality rates.4 Patients with GBC have a mean survival of 6 months, and a 5-year survival rate of 5%.5 The disease is often discovered incidentally following cholecystectomy for benign diseases such as polyps, gallstones, and cholecystitis.6

Gallstone disease is the single most commonly identified risk factor for GBC.1 Gallstone formation is increased with age, female sex, high body mass index (BMI), non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and polyps.7 So, these risk factors are important in GBC. For example, in most populations, GBC is more common in females than in males.1 However, the wide variations in the incidence of GBC in different populations suggest that more factors must be involved that place certain populations at higher risk. Similar to many cancers, various genetic8 and environmental factors combine in the development of GBC, such as chronic infection of the gallbladder, environmental exposure to specific chemicals, heavy metals, and even many dietary factors.9 Inflammation over prolonged periods of time seems to be a critical factor for GBC development,10 while the relative risk of genetic variants requires larger, more comprehensive studies.1

Because GBC is generally a rare disease, it is relatively poorly studied.11 However, its high mortality rate means it is important to fully understand this disease and to identify regions with higher incidence rates where risk factors may combine. A good starting point is to establish reliable epidemiological reports in various populations. In Saudi Arabia, the age-standardised incidence rate (ASIR) for GBC was estimated to be 1.3 per 100,000 individuals in 2018, which is relatively low than in other countries.12 However, to date, there have been no detailed epidemiological analyses of GBC in Saudi Arabia. The objective of this study was to undertake a detailed descriptive epidemiological study of male and female incidence of GBC. To compare the trends over time and to compare regional differences. Therefore, we undertook an analysis of the GBC incidence data provided by the Saudi Cancer Registry (SCR) reports between January 2004 and December 2015.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

In Saudi Arabia, a retrospective study involving various cases on GBC was conducted from 2004 to 2015. GBC-specific data in the country are available in the public domain via SCR reports. As a matter of fact, the data made available most recently from the SCR was released in 2015, which is why the present study aims to examine the pattern of GBC among the country’s males as well as females between 2004 and 2015. Accordingly, annual reports are available for 13 administrative provinces in this period that investigated the percentage and number of GBC cases, the crude incidence rate (CIR) and age-standardised incidence rate (ASIR) adjusted by gender, religion, and year of diagnosis. Via these reports, the study was performed to examine gallbladder cancer’s epidemiological pattern across different areas of the kingdom.

Ethical Approval

The data of annual cancer registry in Saudi Arabia are freely available in the public domain via SCR reports. Actually, it is open data for researches to use and study, without restrictions from the SCR. Hence, this study did not require ethical approval at all. Moreover, data on cancer are available from a Saudi cancer registry (SCR) that is based on population and was launched by Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Health (MOH) back in 1994.

Statistical Analysis

The epidemiological data’s elaborative statistics was undertaken through the calculation of the following: CIR/ASIR adjusted on the aforementioned attributes, year of diagnosis, and age-specific incidence rate. This was followed by using the two-sample t-test to ascertain the discrepancies in CIR and ASIR of GBC across both genders from 2004 to 2015 for the purpose of examining GBC-specific pattern in different geographic regions. Additionally, the study entailed Analysis of variance test (ANOVA) for undertaking a comparison CIR and ASIR of GBC (covering both Saudi males and females) in various parts of the nation. Subsequently, GBC gender ratio for the above-mentioned rates was calculated for all variables (independent), including region, age, and the year in which the diagnosis was made.

Results

Gallbladder Cancer Among Male Saudis

Total Cases in Saudi Males

From 2004 to 2015, a total of 702 males’ GBC cases were found to be registered in the SCR, with a slight increase in the number of cases during this period. In 2004, the total number of cases stood at 24 (3.4%), which increased by 4.6% to 56 by 2009-end. In 2010, there was a small decline. Between 2011 and 2015, the total number of GBC cases rose by 1.3% to 82 from 73, the biggest percentage seen in the SCR. Among Saudi males, the overall number of annual cases was 59, an increase of 8.3% (Figure 1).

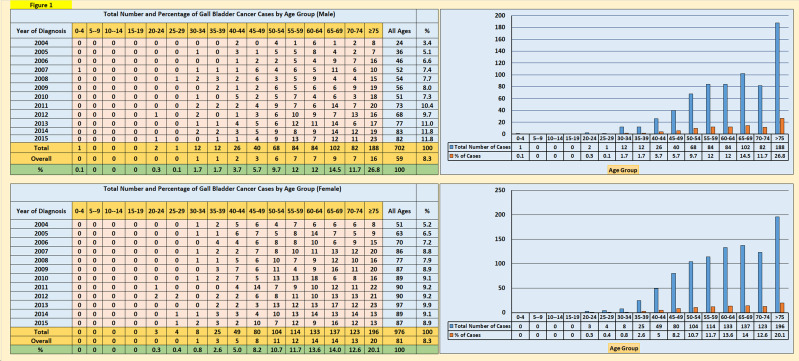

Figure 1.

The total number and percentage of gallbladder cancer cases among male and female Saudis.

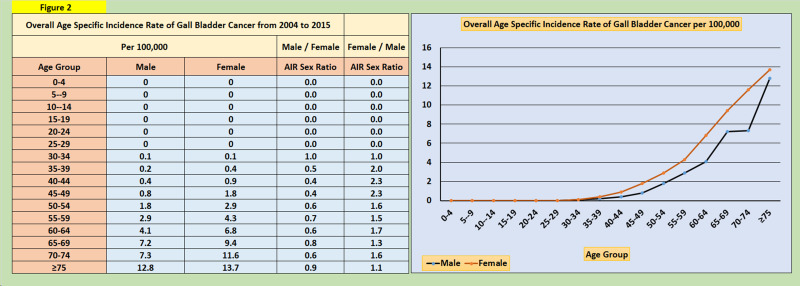

The age groups’ class width from 0 to 4 years was 5 years until 70–74 years. However, all males above the age of 75 were found to be within the same class. Over a 12-year period between 2004 and 2015, the majority of GBC cases were found to be among males above the age of 75, followed by the 65–69 age-group, accounting for 26.8% (16 overall cases annually) and 14.5% (9 overall cases annually). Contrastingly, the lowest percentage and a total number of GBC cases were found in groups in the 0–49 age group (Figure 1). Furthermore, the overall GBC incident rate (age-specific) was found to be high in these age groups: 60–64, 65–69, 70–4, and 75 and above at 4.1, 7.2, 7.3, and 12.8 per 100,000 Saudi males, respectively. However, male-to-female ratio (age-specific incidence) was found to be higher among the 50–75 age group and above in comparison to other age groups aged 0–44 years (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overall incidence rate (age specific) of gallbladder cancer cases among both Saudi genders.

CIR in Saudi Males

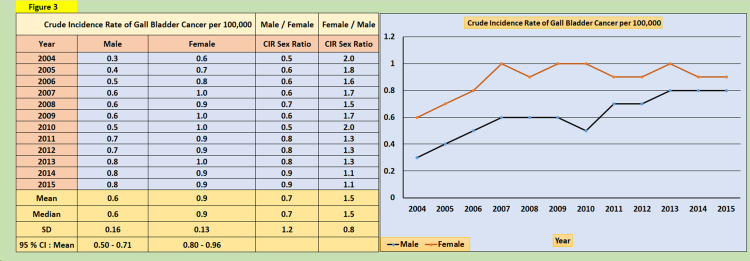

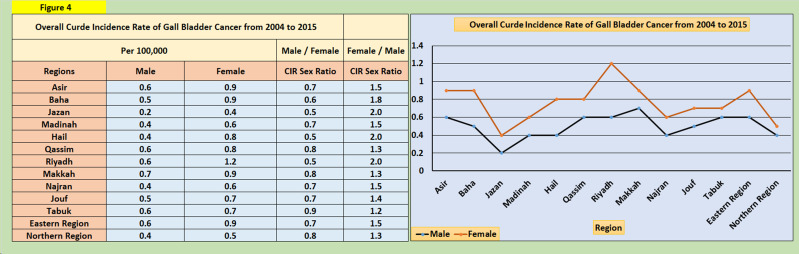

Among Saudi males, GBC cases’ CIR was stratified on the basis of year in which the diagnosis was made between 2004 and 2015. After witnessing a slight rise between 2004 and 2009, a slight reduction was seen a year later in 2010. Meanwhile, stability ensued between 2011 and 2015. In 2004, it was estimated that the GBC’s CIR stood at 0.3/100,000 Saudi males. Between 2011 and 2015, the highest rates witnessed in SCR were CIRs of 0.7 and 0.8/100,000 Saudi males (Figure 3). Additionally, the overall CIR of GBC in males during the study period was 0.6/100,000 males (0.50 to 0.70; 95% CI). According to the findings of two t sample t-tests carried out in an independent manner, the CIR was found to be considerably lower in Saudi males as compared to females P < 0.001; t (22) = −4.568. On the other hand, the overall male-to-female ratio (crude incidence) was 0.7 per 100,000 males from 2004 to 2015. According to Figure 4, the SCR was used to calculate the overall CIR on the basis of region-based stratification across Saudi Arabia per 100,000 males from 2004 to 2015. The ANOVA test did not indicate any major differences in the overall CIR of GBC among Saudi males in all administrative regions, F (12,143) =1.779, P = 0.06. Additionally, the overall male-to-female ratio (crude incidence) was in the 0.5–0.7 range across all areas of the country (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

CIR of gallbladder cancer cases among both Saudi genders.

Figure 4.

Overall CIR of gallbladder cancer cases among both Saudi genders by region.

ASIR in Saudi Males

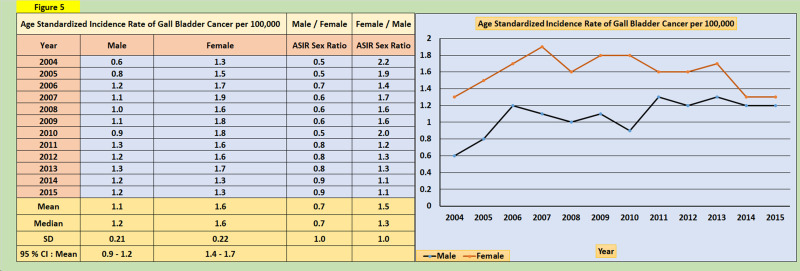

The SCR was also referred to in order to calculate the ASIR of GBC on the basis of year-of-diagnosis stratification between 2004 and 2015 per 100,000 Saudi males. As was observed in CIR, from the 2004–2009 witnessed a marginal increase, before decreasing slightly a year later in 2010, finally increasing steadily between 2011 and 2015 (Figure 5). In 2004, the lowest ASIR was reported at 0.6/100,000 Saudi males. Similarly, the highest rate was in the range of 1.2–1.3 between 2011 and 2015. Meanwhile, the overall ASIR of GBC among the males of Saudi Arabia was found to be 1.1/100,000 males (0.9–1.2; 95% CI) in the twelfth-year period. According to both sample t-tests, Saudi males witnessed a considerably lower ASIR as compared to females P < 0.001; t (22) = −6.322. However, the overall male-to-female ratio (age-standardised incidence) stood at 0.7/100,000 males between 2004 and 2015.

Figure 5.

The ASIR of gallbladder cancer cases among both Saudi genders.

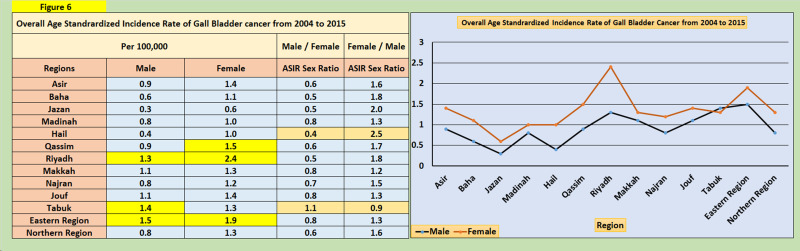

A calculation of the overall ASIR based on region-specific stratification was also made per 100,000 Saudi males between 2004 and 2015, as shown in Figure 6. The highest ASIR of 1.5/100,000 males was found in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern region. Meanwhile, Tabuk’s ASIR was 1.4, followed by Riyadh at 1.3. It was also found that the ANOVA test was more statistically important for these three regions in comparison to other areas (F (12,143)=1.930, P<0.001). At 1.1, Tabuk witnessed the highest male-to-female ratio (age-standardised incidence), thus indicating that the ASIR of GBC was lower among male than female Saudis across all provinces, with the exception of Tabuk (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Overall ASIR of gallbladder cancer cases among both Saudi genders by region.

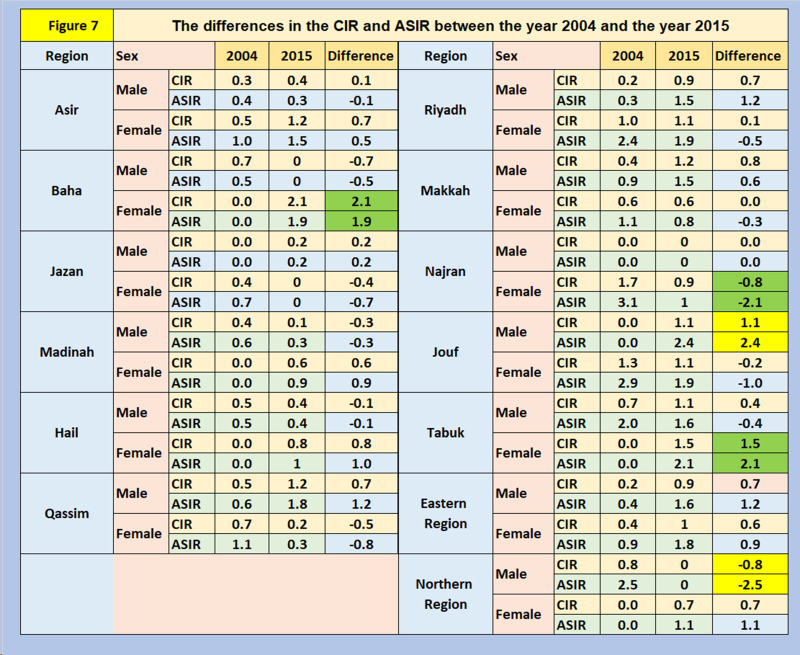

Comparison of CIR and ASIR in Saudi Males

It was deemed necessary to calculate the differences in GBC-based ASIR and CIR among Saudi males from 2004 to 2015 in order to interpret the trend followed by GBC in the country. As far as Saudi males were concerned, the greatest changes in GBC rates were reported in the Jouf region (ASIR: 2.4; CIR, 1.1), whereas the Northern region recorded the lowest changes (ASIR: −2.5; CIR, −0.8). These data provided an indication of the general upward trend of GBC observed among Saudi males residing in the Jouf region, while the ones residing in the Northern region saw a downward trend (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The differences in the CIR and ASIR in Saudi Arabia.

Gallbladder Cancer Among Female Saudis

Total Cases in Saudi Females

From January 2004 to December 2015, 976 GBC cases were recorded among Saudi females. The total number of cases rose slightly during the 12-year period. In 2004, the total number of cases was 51, an equivalent of 5.2%. The number of cases rose to 86 by 2007-end, accounting for an increase of 3.6%. This, in turn, was followed by a slight reduction in 2008. From 2009 to 2015, the number and percentage of GBC cases remained stable between 8.9% and 9.1% with no significant increase during the period. Between 2004 and 2015, the overall percentage and number of GBC among females were 8.3% and 81 cases annually, respectively (Figure 1).

During the same period, Saudi women in the 75 and above age-group were found to have the highest diagnosis rate of GBC, accounting for 20.1% (or 20 cases annually). They were followed by the 65–69 age group, which contributed 14.0% of the overall GBC cases, or a total of 14 cases. Contrastingly, the lowest overall percentage and number of GBC cases were recorded in the 0–49 age group. Moreover, the overall GBC incident rate (age-specific) was high in Saudi females aged 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, and 75 and above, with the corresponding figures at 6.8, 9.4, 11.6 and 13.7/100,000 females (Figure 2).

CIR in Saudi Females

The CIRs of GBC cases among female Saudis increased slightly between 2004 and 2007, before being stable from 2008 to 2015. In 2004, the estimated CIR stood at 0.6/100,000 females. Between 2005 and 2015, the estimated range of CIRs was stable (0.7–1.0/100,000 females). Between 2004 and 2015, the overall GBC’s CIR was 0.9 per 100,000 females (0.80 to 0.96; 95% CI) (Figure 3). Meanwhile, according to the overall GBC’s CIR calculated based on region-specific stratification between 2004 and 2015 per 100,000 females, Riyadh recorded the highest total CIR (1.2/100,000 females). At the same time, the result of ANOVA test for Riyadh was found to be significant (P=0.04; F (12,143) =1.871) in comparison to Saudi Arabia’s Northern region and Jazan, which recorded 0.5 and 0.4 per 100,000 females (Figure 4).

ASIR in Saudi Females

From the SCR, a calculation was made of GBC’s ASIRs whose stratification was done based on year-of-diagnosis between 2004 and 2015 per 100,000 Saudi females. It is noteworthy that the 2004–2007 period witnessed a small increase. However, this was followed by a steady decline between 2008 and 2015. It was in the year 2007 that the highest GBC’s ASIRs were witnessed at 1.9/100,000 females. In a similar vein, the lowest ASIRs were recorded in 2014 as well as 2015, with the figure being 1.3/100,000 Saudi females. It is also pertinent to note that the ASIR within females in Saudi Arabia was 1.6/100,000 females between 2004 and 2015 (95% CI, 1.4 to 1.7) (Figure 5). In that context, the overall ASIR whose stratification was done in a region-specific manner between 2004 and 2015 demonstrated that Riyadh witnessed the highest total ASIR at 2.4/100,000 females. The Eastern region witnessed the second-highest total ASIR at 1.9, followed by Qassim at 1.5/100,000 females. For this reason, it was observed that the ANOVA test showed statistical importance for these areas in comparison to other regions of the kingdom, F (12,143) =2.496, P < 0.005 (Figure 6).

Comparison of CIR and ASIR in Saudi Females

Discrepancies in ASIR and CIR among females in Saudi Arabia from 2004 to 2015 were deduced as well for examining the trend of GBC in various parts of the country. Tabuk and Baha witnessed the highest changes with regard to GBC rates among females (CIR, 1.5 and 2.1; ASIR, 2.1 and 1.9), while the Najran was found to record the lowest changes (ASIR, −2.1; CIR, −0.8). These data provided an indication of the general upward trend of GBC observed among Saudi females residing in Tabuk as well as Baha. On the other hand, the females residing in the Najran region witnessed a downward trend (Figure 7).

Discussion

It is essential to investigate the epidemiological rates of GBC cases among the Saudi population for all provinces in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, the aim of this study was to undertake a descriptive analysis of the epidemiology of GBC in Saudi Arabia from 2004 to 2015. Based on the PubMed database, this is the first study on spatial-temporal pattern of GBC among Saudi males and females in various provinces of the country. The results provide real trends in GBC at different periods of time in Saudi Arabia. It showed that 1678 GBC cases, 702 in males and 976 in females, were registered between 2004 and 2015 in Saudi Arabia and those aged 75 years and over were the highest exposed to GBC among both sexes. In males, the overall CIR was 0.6 per 100,000 with similar rates in the administrative provinces of the country. The overall CIR among Saudi females was 0.9 per 100,000. Riyadh had the highest overall CIR (1.2 per 100,000), significantly higher than Jazan and the Northern region of the country (0.4 and 0.5 per 100,000). The CIR was lower among males than females with a ratio of 0.7 (range 0.2 and 0.7 in all regions of Saudi Arabia). Overall ASIR was 1.1 per 100,000 among Saudi males and 1.6 per 100,000 among Saudi females showing a significant difference. The overall male-to-female ratio for both CIR and ASIR was 0.7. For females, Riyadh had the highest overall ASIR for GBC at 2.4 per 100,000. For males, the Eastern Region of Saudi Arabia had the highest overall ASIR for GBC at 1.5 per 100,000.

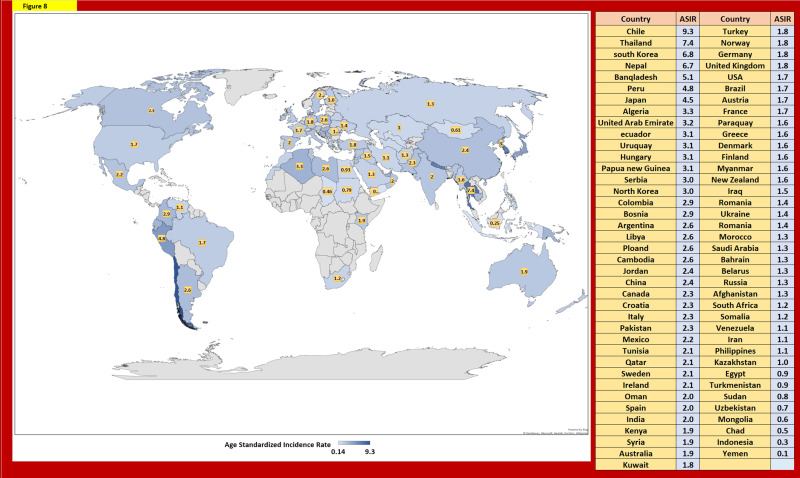

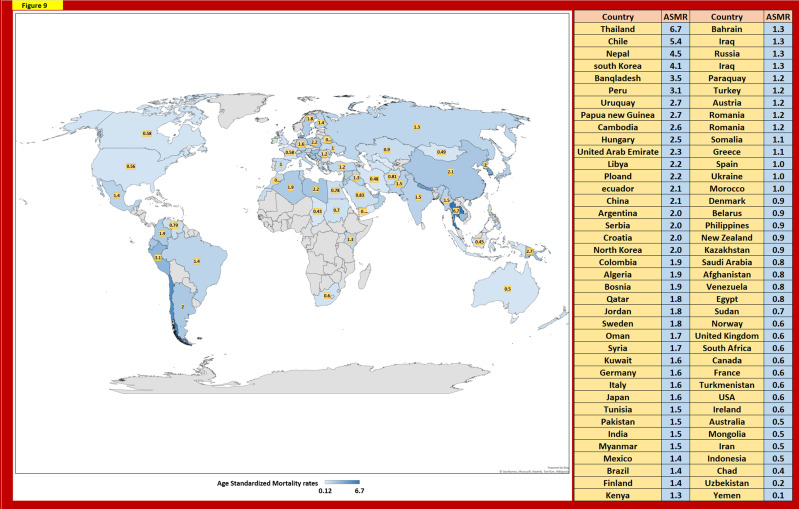

In 2018, it is estimated that the ASIR for GBC in Saudi Arabia among both genders was 1.3 per 100,000 persons. The rate is slightly low in comparison with Arabian countries.12 The approximate ASIR of GBC worldwide in 2018 was 2.2 per 100,000 according to GLOBOCAN.13 In the Arabian Gulf, the United Arab Emirates had the highest rate of GBC among both genders at 3.2 per 100,000 persons; this rate was 2.5 times higher than Saudi Arabia (Figure 8). Furthermore, the mortality rate (age-standardised) of GBC among both genders were documented in Saudi Arabia at 0.8 per 100,000 persons.12 This mortality rate was slightly low in comparison with other Arab states (Figure 9). In addition, the United Arab Emirates had the highest mortality rate (age-standardised) of GBC among both genders at 2.3 per 100,000 persons; this rate was 2.9 times higher than Saudi Arabia.12 The results of this study also suggest that the incidence of GBC is relatively low in Saudi Arabia. Comparison of the Saudi ASIR of 1.1 per 100,000 males and 1.6 per 100,000 females is similar to the USA with an overall ASIR from 1973 to 2009 of 1.4 per 100,000,14 or 1.6 per 100,000 from 1999 to 2013.15 Another study from the US found a rate of 1.13 cases per 100,000 persons each year between 2007 and 2011.16 This compares to the CIRs of 0.6 per 100,000 males and 0.9 per 100,000 females in this study. However, the incidence of GBC differs widely in various populations. The highest recorded incidence rates are in Chile with 9.7 new cases for every 100,000 persons each year and in the regions of Los Lagos and Los Ríos, rates as high as 28.5 per 100,000 women.17 The results of this study show variations in pattern and trend of GBC in different populations within Saudi Arabia. So, they highlight that GBC should not be ignored because of the overall low incidence-mortality rate (age-standardised).

Figure 8.

ASIR of gallbladder cancer (World) in 2018, all ages, both genders.

Figure 9.

ASMR of gallbladder cancer (World) in 2018, all ages, both genders.

This study found that overall, the total number of GBC cases increased slightly from 2004 to 2015; however, while the number in males showed an increasing trend over the whole period, in females it seemed to reach a peak in 2013 and then decreased slightly. Worldwide the rates of GBC increased slightly from ASIR 2.0 per 100,000 in 2008 to 2.2 per 100,000 in 2012 and then appear to have remained fairly constant until 2018.2,13,18 So, the results of this study appear to be generally similar to the situation worldwide.

GBC rates tend to increase with age in most populations.3 The results of this study show that the disease occurred in a significant proportion among those aged 75 years and over, while those aged younger than 50 years were less affected by GBC. These findings are consistent with the findings of other studies that showed the average age of diagnosis for GBC in the USA was 72 years old, with more two thirds of patients with GBC over the age of 65 years.19 Similar average ages of diagnosis are found in Western European populations3 However, some other populations find differences, for example, the mean age of diagnosis is as low as 51±11 years in India.20

In Saudi Arabia, GBC is more common in Saudi females than males. The overall CIR and ASIR of GBC from 2004 to 2015 were both two-fold higher in Saudi women than men. Globally, GBC also occurs more commonly in females than in males, and the risk of developing it increases approximately two to six times among women than men.21 The incidence rates in the USA were also significantly higher in females than males (1.7 vs 1.0).14 In India, the female to male ratio varies from 3:1 to 4.5:1.20 The most likely reason for these elevations is that the female hormone oestrogen raises the saturation of cholesterol in the bile, and then enhances the risk of gallstone formation.22 It is known that gallstones and biliary duct stones are positively correlated with chronic inflammation of the gallbladder, which leads to the development of metaplasia, hyperplasia, dysplasia and finally gallbladder carcinoma.19,23

The results of this study showed variations in ASIRs between regions in Saudi Arabia for both males and females. For males, the ASIR was highest in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia then Tabuk and Riyadh and these three areas were significantly higher than in other areas. In females, the highest ASIR was in Riyadh but Jazan was also significantly lower than in other regions. Males showed no regional differences in CIR, but females also showed a significantly higher CIR in Riyadh than Jazan or the Northern region of Saudi Arabia. The most likely reasons for variations in the incidence of GBC are that Saudis in Riyadh and Eastern region were frequently exposed to the factors associated with a higher risk of GBC, while those in Jazan were frequently exposed to the factors protective elements of GBC in comparison with other provinces of the country. Among other risk factors, obesity with high BMI >30 kg/m2 and diabetes may play a major role in increasing the risk of developing GBC.24 The relative risk of getting GBC is increased among overweight and obese individuals by 1.15 and 1.66, respectively.19 In addition, a systematic review of 20 published studies found that the relative risk of getting GBC among people with diabetes is increased by 1.56 times compared to people without diabetes.25 The highest prevalence of obesity in Saudi Arabia is thought to be in Riyadh at 35%, while the rate of diabetes in Riyadh among males and females is 20 times greater than in Jazan.26 In the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia, Aldossary et al27 reported that 50% of GBC Saudi patients had diabetes and hypertension. They also found that 75% of GBC Saudi patients had gallstones, which is a significant risk factor for GBC.27 These findings may support our results that GBC is a significant type of cancer in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia, which contributes to the increase of overall ASIR from 2004 to 2015. These studies also suggest reasons why the results of this study indicated the highest overall incidence of GBC among male and female Saudis were recorded in Riyadh and the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia.

The present study indicates that the ASIR of GBC is higher among Saudi females than males in all regions of Saudi Arabia, except in Tabuk. This result highlights that pattern of the disease is different in the region of Tabuk compared to other parts of Saudi Arabia. The most likely explanation for this higher ASIR of GBC among men than women is that males in that region are more exposed to specific risk factors of GBC than females. However, it is very difficult to identify the causes without conducting analytical epidemiological studies to examine the risk factors associated with GBC among both genders of Saudis. So, a case-control study must be carried out in Tabuk, to determine the factors that increase the risk of GBC. However, it is suggested that experts of cancer epidemiology may also need to examine the relationship between the risk-protective factors and GBC in Riyadh, the Eastern region, Tabuk, and Jazan, which contribute to the variations in the incidence of GBC in Saudi Arabia to fully understand this pattern.

The changes in the CIR and ASIR of GBC from 2004 to 2015 were analysed in different provinces of Saudi Arabia. The largest changes in rates were documented in Tabuk and Baha among female Saudis, and in Jouf among male Saudis, which indicated that rates were increasing in these regions and the populations became more at risk of GBC. Furthermore, the smallest changes in rates of GBC were detected in the Northern region among male Saudis, and in Najran among female Saudis. These regions showed a decreasing-trend in rates and suggest that male and female Saudis living in these regions were less affected by GBC over the 12-year period.

This study has some limitations. As a retrospective epidemiological analysis, we can only present data on the characteristics of the population with no cause and effect analysis. Therefore, we can only speculate on reasons for variations in incidence rates between regions. Further study is needed to fully investigate these factors. The data from the SCR were limited to 2015, so the current situation for GBC in Saudi Arabia will need to be evaluated at a later date.

Conclusions

The results of this epidemiological analysis of GBC incidence show that the overall rate is relatively low in Saudi Arabia compared to other countries worldwide. GBC was most frequently diagnosed in the over 75 years age group. The rates were higher in females than males in all regions except Tabuk. The pattern of GBC incidence varied according to the region of Saudi Arabia. In females, the highest ASIR was in Riyadh, Eastern region, and Qassim but Jazan was also significantly lower than other regions. In males, ASIR was highest in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia then Tabuk and Riyadh and these three areas were significantly higher than in other areas. Further analytical epidemiological studies should be conducted to identify the potential risk factors of GBC in Saudi Arabia.

Ethical Approval and Patient Confidentiality

The authors declare that there is no ethical concern regarding the publication of this article.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Schmidt MA, Marcano-Bonilla L, Roberts LR. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and genetic risk associations. Chin Clin Oncol. 2019;8(4):31. doi: 10.21037/cco.2019.08.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hundal R, Shaffer EA. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wernberg JA, Lucarelli DD. Gallbladder cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2014;94(2):343–360. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2014.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy AD, Murakata LA, Rohrmann CA Jr. Gallbladder carcinoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21(2):295–314;questionnaire, 549–255. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr16295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavallaro A, Piccolo G, Di Vita M, et al. Managing the incidentally detected gallbladder cancer: algorithms and controversies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(Suppl 2):S108–S119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.08.367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shabanzadeh DM, Sorensen LT, Jorgensen T. Determinants for gallstone formation - a new data cohort study and a systematic review with meta-analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(10):1239–1248. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1182583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sicklick JK, Fanta PT, Shimabukuro K, Kurzrock R. Genomics of gallbladder cancer: the case for biomarker-driven clinical trial design. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(2):263–275. doi: 10.1007/s10555-016-9602-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma A, Sharma KL, Gupta A, Yadav A, Kumar A. Gallbladder cancer epidemiology, pathogenesis and molecular genetics: recent update. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(22):3978–3998. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i22.3978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui X, Zhu S, Tao Z, et al. Long-term outcomes and prognostic markers in gallbladder cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(28):e11396. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aloia TA, Jarufe N, Javle M, et al. Gallbladder cancer: expert consensus statement. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17(8):681–690. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2018. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today. Accessed September 14, 2020.

- 13.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahman R, Simoes EJ, Schmaltz C, Jackson CS, Ibdah JA. Trend analysis and survival of primary gallbladder cancer in the United States: a 1973–2009 population-based study. Cancer Med. 2017;6(4):874–880. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Dyke AL, Shiels MS, Jones GS, et al. Biliary tract cancer incidence and trends in the United States by demographic group, 1999–2013. Cancer. 2019;125(9):1489–1498. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henley SJ, Weir HK, Jim MA, Watson M, Richardson LC. Gallbladder cancer incidence and mortality, United States 1999–2011. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(9):1319–1326. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villanueva L. Cancer of the gallbladder-Chilean statistics. Ecancermedicalscience. 2016;10:704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rawla P, Sunkara T, Thandra KC, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of gallbladder cancer. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019;5(2):93–102. doi: 10.5114/ceh.2019.85166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutta U, Bush N, Kalsi D, Popli P, Kapoor VK. Epidemiology of gallbladder cancer in India. Chin Clin Oncol. 2019;8(4):33. doi: 10.21037/cco.2019.08.03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konstantinidis IT, Deshpande V, Genevay M, et al. Trends in presentation and survival for gallbladder cancer during a period of more than 4 decades: a single-institution experience. Arch Surg. 2009;144(5):441–447; discussion 447. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schirmer BD, Winters KL, Edlich RF. Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2005;15(3):329–338. doi: 10.1615/JLongTermEffMedImplants.v15.i3.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Everson GT, McKinley C, Kern F Jr. Mechanisms of gallstone formation in women. Effects of exogenous estrogen (Premarin) and dietary cholesterol on hepatic lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest. 1991;87(1):237–246. doi: 10.1172/JCI114977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver. 2012;6(2):172–187. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.2.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu J, Yan S, Wang B, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of gallbladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(1):63–72. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alghamdi IG, Alghamdi MS. The incidence rate of liver cancer in Saudi Arabia: an observational descriptive epidemiological analysis of data from the Saudi Cancer Registry (2004–2014). Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:1101–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aldossary MY, Alayed AA, Amr SS, Alqahtani S, Alnahawi M, Alqahtani MS. Gallbladder cancer in Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2018;35:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]