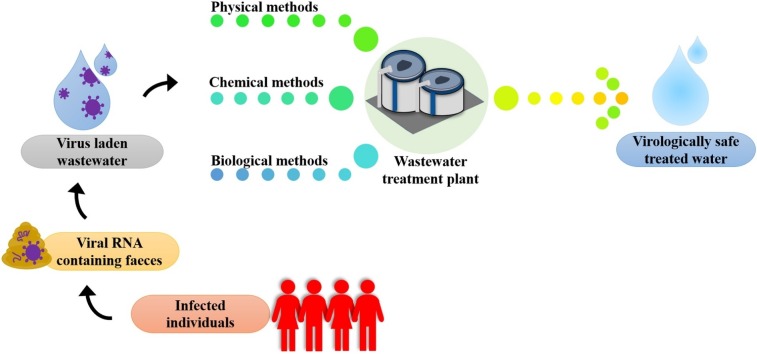

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: ASP, Activated Sludge Process; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; dsDNA, Double stranded Deoxyribonucleic Acid; dsRNA, Double stranded Ribonucleic acid; DUV-LED, Deep Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diode; E.coli, Escherichia coli; EPS, Exopolysaccharide; LRV, Log Reduction Value; MBR, Membrane Bioreactor; MERS-CoV, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus; MLSS, Mixed Liquor Suspended Solids; PMR, Photocatalytic Membrane Reactor; RH, Relative Humidity; SARS-CoV, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; SBBGR, Sequencing Batch Biofilter Granular Reactor; SEM, Scanning Electron Microscopy; SSF, Slow Sand Filtration; ssRNA, Single stranded Ribonucleic Acid; UASB, Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket; UN SDG, United Nations Sustainable Development Goal; UV, Ultraviolet; WHO, World Health Organisation; WWTP, Wastewater Treatment Plant

Keywords: Microalgaee, Phycoremediationn, Waterbornee, COVID-19

Abstract

The world is combating the emergence of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by novel coronavirus; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Further, due to the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in sewage and stool samples, its transmission through water routes cannot be neglected. Thus, the efficient treatment of wastewater is a matter of utmost importance. The conventional wastewater treatment processes demonstrate a wide variability in absolute removal of viruses from wastewater, thereby posing a severe threat to human health and environment. The fate of SARS-CoV-2 in the wastewater treatment plants and its removal during various treatment stages remains unexplored and demands immediate attention; particularly, where treated effluent is utilised as reclaimed water. Consequently, understanding the prevalence of pathogenic viruses in untreated/treated waters and their removal techniques has become the topical issue of the scientific community. The key objective of the present study is to provide an insight into the distribution of viruses in wastewater, as well as the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2, and its possible transmission by the faecal-oral route. The review also gives a detailed account of the major waterborne and non-waterborne viruses, and environmental factors governing the survival of viruses. Furthermore, a comprehensive description of the potential methods (physical, chemical, and biological) for removal of viruses from wastewater has been presented. The present study also intends to analyse the research trends in microalgae-mediated virus removal and, inactivation. The review also addresses the UN SDG ‘Clean Water and Sanitation’ as it is aimed at providing pathogenically safe water for recycling purposes.

1. Introduction

As per WHO, about 80 % of the diseases that occur worldwide are waterborne [1]. The poor water quality and unhygienic water attribute to approximately 1.5–12 million deaths per year [2]. Water pollution and associated waterborne diseases are a major concern in the Indian subcontinent as well. Due to polluted waters, 69.14 million cases of major waterborne diseases, namely diarrhoea, cholera, typhoid, and viral hepatitis, caused 10,378 deaths in the country during 2013–2017 [3].

Viruses are a major causative agent of many lethal diseases, including gastroenteritis, hepatitis, and respiratory illnesses. The present COVID-19 pandemic declared as a health emergency by the WHO is also caused by a novel coronavirus; SARS-CoV-2 [4]. The virus is characterised as a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus belonging to the Betacoronavirus family [5]. Recent reports demonstrated the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the wastewater treatment systems [6,7]. A study in Australia confirmed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater sampled from a catchment area [8], while another study detected SARS-CoV-2 in the wastewater sampled from influent of an urban treatment facility in Massachusetts [9]. Moreover, various studies have reported the presence of viruses in treated wastewater [10,11] thus, increasing the risk of disease outbreaks. Hence, it may be inferred that viral contaminants are present not only in the wastewater but also in the treated water (in case of inefficiency/absence of disinfection). The contaminated water further may serve as transmission routes for the viruses, thus necessitating virus removal from wastewater.

Various conventional approaches have been applied for virus removal from wastewater. However, most of these techniques have been reported to be inefficient for the absolute removal of viruses from the wastewater, and therefore, imposes a serious threat to human health [12]. Hence, alternative approaches are being explored for efficient wastewater disinfection [13]. Further, understanding the fate of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater treatment plants is of prime importance with more research required to comprehend the removal of the virus in various treatment stages; importantly, where the treated wastewater may be utilised for various reclamation purposes [14]. The concept of phycoremediation has been gaining impetuous and involves the use of micro/macro-algae for removal of toxic/non-toxic contaminants from different kinds of solid, liquid, and gaseous waste [15]. Recently, an extremophile Galdieria sulphuraria has been utilised for the development of a microalgae-based wastewater treatment system that demonstrated high removal rates for noroviruses, coliphages, and enteroviruses [16]. Some recent studies have elucidated various removal mechanisms, namely; adsorption [17], pH shift [18], sunlight-mediated inactivation [19], and predation [20] for microalgae-mediated virus inactivation [21].

Considering all the facts related to recent development in the virus removal from wastewater, the present study aims to compile a state-of-the-art consolidated review on (i) occurrence and fates of viruses in wastewater, (ii) associated risks of disease outbreaks and, (iii) possible methods (conventional and advanced) for virus disinfection during wastewater treatment.

2. Viruses and wastewater

2.1. Prevalence of viruses in treated wastewater; a matter of serious concern

A wide variation in the removal of viral pathogens by the conventional wastewater treatment processes have been reported, thereby posing a serious threat to public health. A study by Rosario et al. [22] has shown the presence of a novel DNA virus in both secondary treated and the disinfected wastewater effluent. Another interesting study by Chatterjee et al. [23] has reported strains of giant viruses in three environmental samples, namely a sludge sample and a drying bed sample from the wastewater treatment plant, and a pre-filter of household water purifier. Another study by Prevost et al. [24] revealed a high presence of adenovirus, norovirus, and rotavirus in the wastewater treatment plant effluents, which further contaminated the Seine River in Paris. Hence, there is a high possibility of the presence of other dangerous viruses in the treated effluent, particularly from the wastewater treatment plant having inadequate treatment facilities to handle virus-containing sewage.

For the particular case of SARS-CoV-2, there is a lack of sufficient literature and evidence for their presence in treated or disinfected wastewater effluent. However, various reports are now emerging regarding the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater treatment systems [6,25] (Table 1 ). The wastewater samples collected from the influent of an urban wastewater treatment plant in Massachusetts were found to be positive for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 [9]. The virus was detected in the wastewater samples by Reverse Transcriptase-quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction and DNA sequencing. A similar study by Ahmed et al. [8] detected SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater collected from a catchment region in Australia. In light of the present literature, Table 1 represents the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 and other human pathogenic coronaviruses in the wastewater.

Table 1.

Prevalence of human pathogenic coronaviruses in wastewater.

| Virus | Wastewater | Place | Concentration range | Remarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | WWTP | USA | ⁓100 × 103 with lowest value of ⁓104 copies L−1 sewage | Higher viral titers obtained than expected from clinically confirmed cases | [9] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Catchment regions | Australia | 19 and 120 RNA copies L−1 of untreated wastewater | Results were in agreement with clinically confirmed cases | [8] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Six WWTPs | Spain | 2.5 × 105 RNA copies L−1 of untreated wastewater | 11 % secondary treated samples positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA | [130,131] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Three WWTPs | France | 5 × 104 to 3 × 106 RNA copies L−1 of raw wastewater | Change in virus concentration was in accordance with the trend of diagnosed COVID-19 cases | [132] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | WWTP (influent, secondary treated water); river water | Japan | 2.4 × 103 RNA copies L−1 in one out of 5 secondary-treated samples | No SARS CoV-2 RNA was detected in all the influent and river samples | [131] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Seven cities and airport | Netherlands | n.d. | SARS-CoV-2 was detected in high concentrations in sewage samples, even when COVID-19 incidents were few | [25] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Three WWTPs | Italy | n.d. | SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in 6 out of 12 influent wastewater samples | [133] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | WWTP | India | n.d. | Obtained Ct values in accordance with the increasing COVID-19 cases; SARS-CoV-2 genes detected in all influent samples | [134] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Six WWTPs | India | n.d. | SARS-CoV-2 genome was detected at an ambient temperature of 40−45 °C | [135] |

| Alphacoronavirus Betacoronavirus Hepatitis A virus |

Water channels | Saudi Arabia | HAV - 5.0 × 101 to 1.9 × 104 RNA copies L−1 of surface water | HAV was detected in 38 % of the samples, while one sample was positive for an Alphacoronavirus | [136] |

| Coronaviridae | Lake Balkhash | Kazakhstan | n.d. | 37 families of viruses were identified. Coronaviridae represented 0.02–0.09% of the entire viral population. | [137] |

Abbreviations: WWTP = Wastewater treatment plant, n.d. = not determined.

2.2. Viral contamination of food

One of the major routes of the outbreak of the viral disease has been related to the consumption of contaminated foods, owing to the survival ability of viral pathogens on the food for extended periods [26]. As explained by Richards [27] and Harris et al. [28], the food-borne viral contamination can be categorised as (i) pre-harvest and (ii) post-harvest contamination. The utilisation of reclaimed wastewater and sewage sludge for irrigation and crop fertilizer, respectively, constitute the pre-harvest contamination. Improper handling by workers and consumers, contaminated transport containers or harvesting equipment and, contaminated rinse water has been linked with the post-harvest contamination of the raw food. Some studies have attributed the incidents of enteric viral diseases (hepatitis A, acute gastroenteritis) with the consumption of raw vegetables and unhygienic conditions at the associated places [27,29]. The consumption of shellfish grown in contaminated or sewage polluted marine waters is the most prominent food-borne transmission of enteric viruses [30]. The filter-feeding characteristic of these organisms results in the accumulation of positive-stranded RNA viruses in their gills and digestive glands [31]. It is noteworthy here that SARS-CoV-2 is also a positive single-stranded RNA virus [32]. Hence, it is likely possible that SARS-CoV-2 may also accumulate in the aquatic invertebrates, subject to the survival of the virus in the water and aquatic environments. The SARS-CoV-2 is predicted to be food-borne and reportedly originated from the Wuhan seafood market of China and has resulted in the COVID-19 pandemic [33].

2.3. Plausible faecal-oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2

A recent report by WHO has stated that the novel coronavirus can persist in sewage, faeces, and on surfaces [34]. Besides, in a recent article, Wu et al. [35] reported the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the faecal samples from patients with COVID-19 disease. Similarly, Zhang et al. [36] detected SARS‐CoV‐2 viral RNA in the faecal samples of children during their recovery period of COVID‐19. Notably, live SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the faeces of some patients, thus, highlighting the possibility of SARS-CoV-2 transmission by the faecal route [37].

Concerning the current scenario of increasing cases of the pandemic COVID-19, different transmission routes of SARS-CoV-2 need to be identified to prevent the rapid spread of disease. As emphasised by Qu et al. [38], the faecal transmission routes for SARS-CoV-2 should also be considered owing to its detection in the stool samples of infected patients. Different studies have shown the presence of coronaviruses in stool samples and, thus, the sewage systems. A study by Weber et al. [39] has revealed the survival of SARS-CoV in a stool sample for 4 days. Therefore, these viral pathogens may invade into the surface water bodies if the contaminated wastes, such as sewage having mixed excreta and urine from the patients, are directly discharged to the environment without proper treatment. An inspection of the faecal transmission route can help to elucidate the disease extent prevalent much before the infected persons experience the symptoms [40,41]. Such stringent inspection would help in better management of the disease and prevention of its spread to other areas.

2.4. Waterborne and non-waterborne viruses

In a study by Xagoraraki and O’Brien [2] an interesting approach has been adopted to study the wastewater viruses by their classification into two categories, namely, the waterborne and non-waterborne viruses. The waterborne viruses are characterised as the viral pathogens transmitted by contaminated water while possessing a moderate to high health significance as elucidated by WHO [42]. Some of the prominent examples of waterborne viruses include hepatitis virus, rotavirus, caliciviruses, enteroviruses, and polyomaviruses [43]. On the other hand, the non-waterborne viruses are transmitted by insects (breeding in water), and some can be transmitted between humans and animals by vectors like bats and rodents. Hence, the non-waterborne viral pathogens are also categorised as zoonotic viruses and include Nipah virus, Hantavirus, Zika virus, and the like [2].

2.4.1. Waterborne viruses

The most predominant waterborne viruses are adenoviruses, noroviruses, enteroviruses (especially; the echoviruses, polioviruses, and coxsackieviruses), astroviruses [44], hepatitis A and E viruses [45,46], and rotaviruses [47]. These viruses have been commonly detected in different types of wastewater and effluents; hence, they play a key role in wastewater-based epidemiology [48,49]. The adenoviruses and noroviruses are the most abundant human viruses present in wastewater with concentrations reported as 6.0 × 102 to 1.7 × 108 copies L−1 and 4.9 × 103 to 9.3 × 106 copies L−1 [2]. These have been linked to outbreaks of gastroenteritis and respiratory diseases [48,50]. They have been detected in faeces and urine of infected persons [51] with a 102 to 1011 viral copies reported per gram of the stool sample [52,53]. In addition to these, some other viruses like salivirus (3.7 × 105 to 9.7 × 106 copies L−1 wastewater), torque teno virus (4.0 × 104 to 5.0 × 105 copies L−1 wastewater), sapovirus (1 × 105 to 5 × 105 copies L−1 wastewater), and polyomaviruses (8.3 × 101 to 5.7 × 108 copies L−1 wastewater) are also frequently detected in human faeces and wastewater samples [2]. However, these viruses are rarely studied and thus demand more attention as they are found to be associated with various diseases. For instance, salivirus is reported to be linked with acute flaccid paralysis and gastroenteritis [54], while the polyomaviruses are associated with severe medical conditions like progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, carcinoma, and nephropathy [55].

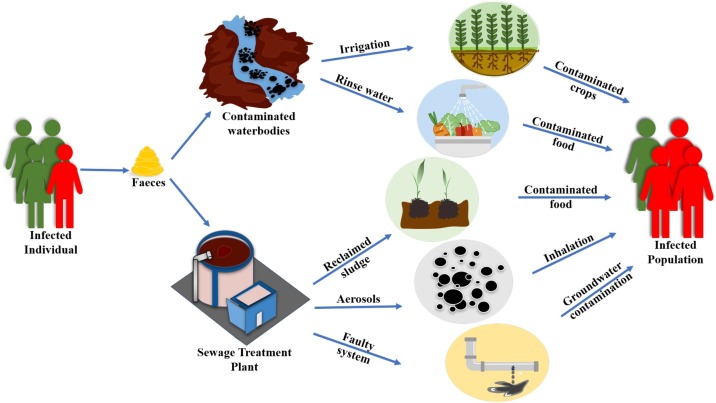

To the best of authors’ knowledge, not much research evidence is available concerning the SARS-CoV-2 transmission as waterborne viruses. However, the presence of SARS-CoV-2 particles in the faecal samples from infected patients, as well as in the wastewater treatment plants, poses a high risk of its transmission through water routes. The possible transmission routes for viral pathogens (including SARS-CoV-2) through contaminated waters have been outlined in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Possible transmission routes of viruses through contaminated water.

2.4.2. Non-waterborne viruses

The non-waterborne viruses have also been detected in human faeces and wastewater. These water-related viruses include various zoonotic viruses like Zika virus, Dengue virus, Yellow fever virus, Nipah virus, and Hantavirus [56,57]. These viruses have the potential to get transmitted from animals to humans through vectors like bats, mosquitos, birds, and rodents. Most non-waterborne viruses have been linked with major disease outbreaks and thus are a significant component of the wastewater-based epidemiology. In studies by Lin et al. [58], the exposure to aerosolised wastewater has been linked with waterborne transmission of zoonotic viruses. Further, high turbulence places like toilet flushing, aeration basins, irrigation systems, and converging sewer pipes served as sites for wastewater aerosolisation [2]. Hence, the transmission risk of SARS-CoV-2 associated with aerosols generated from contaminated sewage and faulty sewage systems also needs to be inspected.

The SARS-CoV-2 also falls under the category of zoonotic viruses. Based on its genome similarity with the bat viruses, the virus is hypothesised to be transmitted to humans from bats [59]. Also, its presence in wastewater systems and further waterborne transmission routes have been elaborated. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 can be considered as both the waterborne and non-waterborne viruses.

2.5. Viral diseases; environmental factors governing virus survival

The presence of viruses in wastewater may lead to various waterborne diseases through contaminated drinking water sources/recreational water and/or food contaminated with sewage wastewater [30]. Over one hundred species of viruses present in sewage-contaminated water are the causative agents of various human diseases like gastroenteritis, conjunctivitis, fever, meningitis, heart anomalies, paralysis, and hepatitis (Table 2 ). It is clear that these viruses easily spread through contaminated waters, and thus their removal from wastewater is a matter of prime concern.

Table 2.

Diseases caused by common waterborne viruses.

| Virus | Genome | Major disease (s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus | dsDNA | Gastroenteritis, pharyngitis, conjunctivitis, fever | [138] |

| Astrovirus | ssRNA | Gastroenteritis, diarrhoea | [139] |

| Coxsackievirus | ssRNA | Hand foot and mouth disease, myocarditis, paralysis, meningitis, fever, vesicular pharyngitis | [140] |

| Echovirus | ssRNA | Gastroenteritis, meningitis, fever, respiratory disease | [12] |

| Hepatitis A virus | ssRNA | Hepatitis A | [141] |

| Hepatitis E virus | ssRNA | Hepatitis E | [141] |

| Norovirus | ssRNA | Gastroenteritis, fever | [142] |

| Poliovirus | ssRNA | Poliomyelitis | [143] |

| Polyomavirus | dsDNA | Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, carcinoma, nephropathy | [144] |

| Rotavirus | dsRNA | Gastroenteritis, diarrhoea | [138] |

| Salivirus | ssRNA | Acute flaccid paralysis, gastroenteritis | [145] |

| Sapovirus | ssRNA | Gastroenteritis | [146] |

Abbreviations: dsDNA = Double stranded deoxyribonucleic acid; dsRNA = Double stranded ribonucleic acid; ssRNA = Single stranded ribonucleic acid;

The survival of viruses in the wastewater is chiefly governed by prevalent temperature and RH [60]. The viruses demonstrate the highest survival at lower temperatures, whereas higher temperatures are associated with protein and nucleic acid denaturation and destruction of the viral capsid structure [61]. The higher temperatures may also be utilised for inactivation of coronaviruses (enveloped viruses) [62] as they demonstrate high susceptibility to environmental changes. Once the envelope is disrupted, the particle loses its pathogenicity and becomes inactive. A recent bench-scale study on SARS-CoV-2 inactivation reported a significant decrease in the number of viral RNA copies at high temperatures and higher survival at lower temperatures [63]. More than 6-log reduction was achieved for heat inactivation assay performed at 92 °C for 15 min than assays performed at 56 °C for 30 min and 60 °C for 60 min [63]. Similarly, the SARS-CoV-2 titre reduced by 1.46 log units at 70 °C within 5 min, whereas only ⁓ 0.7 log unit reduction was obtained after 14 days of incubation at 4 °C [64]. Hence, inactivation protocols employing higher temperatures could be explored for SARS-CoV-2 inactivation.

Reports have also emphasised the role of RH on the survival of SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV [65]. Further, SARS-CoV has been reported to remain viable at 22−25 °C and 40–50 % RH for a period of 5 days and exhibits the potential to survive up to 2 weeks after drying [62]. Similar studies on MERS-CoV have mentioned high viability of virus at 20 °C and 40 % RH on different surfaces for 48 h [66].

The optimum pH for virus survival varies from species to species. However, the SARS-CoV-2 has been reported to be stable under a wide pH range of 3–10 and, thus, possesses a high survival rate in wastewater [64]. Thus, it may be concluded that various climatic conditions influence the spatial and temporal distribution of viruses in wastewater. Therefore, there is an urgent need for multifarious research interventions towards generating the survival data for SARS-CoV-2.

3. Potential methods for virus removal from wastewater

In view of the above literature, it is evident that viruses are abundant in the wastewater, thereby signifying the urgent need for wastewater disinfection. The risk of epidemics is enhanced by constraints of the small size of viruses in the wastewater. An efficient and cost-effective wastewater treatment is thus required to produce safe water for reuse and recycle.

The conventional wastewater treatment systems are comprised of various physical, chemical, and biological processes that are aimed at the removal of biodegradable organics and suspended solids [67]. Moreover, some processes like the conventional activated sludge process, flocculation sedimentation, and sand filtration have been reported efficient for pathogen removal from wastewater [68]. The pathogen removal efficiency of treatment processes is represented by the LRV [69] defined as the relative number of live microbes eliminated from a system by any removal process and expressed as,

| (1) |

where; cb and ca denotes the number of viable microbes before and after treatment.

Various processes like adsorption, filtration, UV disinfection, and activated sludge process have been attempted for the removal of viruses from wastewater (Table 3 ). The conventional treatment systems employing activated sludge process and chlorination achieved the removal of torque teno virus and adenovirus with a lower LRV of 1.6 and 2.1 ± 0.53, respectively [70]. Contrary to the obtained lower LRV, a higher LRV of 5.5 was obtained for adenovirus by MBR, which also achieved efficient removal of enterovirus (5.1 LRV) and norovirus genogroup II (3.9 LRV) [71]. Based on the present literature, Table 3 provides a glimpse of the various conventional and advanced approaches employed for virus removal.

Table 3.

Various methods employed for virus removal.

| Method | Location | Target viruses | Virus removal rate (LRVa or %b) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASP, chlorination | WWTP, Pisa, Italy | Torque teno virus Human adenovirus Rotavirus Norovirus genogroup I Norovirus genogroup II Somatic coliphages |

1.6a 2.1 ± 0.53a 33b 77.8b 11b 2.16 ± 0.42a |

[70] |

| Algae (Galdieria sulphuraria) based WWTP | Primary effluent, WWTP-Las Cruces, New Mexico | Enterovirus Norovirus Somatic coliphages F-specific coliphages |

1.05 ± 0.32a 1.49 ± 0.16a 3.13 ± 0.34a 1.23 ± 0.34a |

[16] |

| Three pond systems and UASB - maturation pond | Two WWT pond systems, Yungas, Bolivia | Enteric viruses (culturable) | 0.8a (3 pond system) 3.1a (UASB - pond) |

[80] |

| Lagooning system | South Catalonia, Spain | Human adenovirus JC polyomavirus Norovirus genogroup I Norovirus genogroup II |

1.18a 0.64a 0.45a 0.72a |

[147] |

| Membrane bioreactor | Traverse City WWTP, USA | Human adenovirus Norovirus genogroup II Enterovirus |

5.5a 3.9a 5.1a |

[71] |

| Pond system | Accra, Ghana | Somatic coliphages F + coliphages |

2.0a 1.5a |

[148] |

| Sedimentation, ASP, UV disinfection | Gold Bar WWTP, Edmonton, Canada | Rotavirus Norovirus Sapovirus Astrovirus Enterovirus Adenovirus JC virus |

1.08 ± 0.5a 1.64 ± 0.39a 1.77 ± 0.39a 1.8 ± 0.54a 2.81 ± 1.06a 2.02 ± 0.36a 2.28 ± 0.52a |

[149] |

Abbreviations: ASP = Activated Sludge Process; UASB = Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket; UV = ultraviolet; WWTP = Wastewater treatment plant.

3.1. Physical treatment methods

The physical wastewater treatment methods rely on the utilisation of various physical barriers and natural forces like Van der Waal forces, gravity, and electrostatic attraction to achieve contaminant removal from wastewater [72]. The physical unit processes like sedimentation, adsorption, and filtration have been reported to remove the viral pathogens to some extent.

3.1.1. Sedimentation

Recent studies have reported virus removal through the sedimentation process [20,73]. The adsorption of virus particles to large settleable solids followed by sedimentation was considered as a major removal mechanism in various treatment plants [20]. The terminal velocity of a discrete suspended solid settling under gravity is described by;

| (2) |

where, V, g, ρp, ρ, D and CD represent the settling velocity (m sec−1), acceleration due to gravity (m sec-2), particle density (kg m-3), water density (kg m-3), particle diameter (m) and drag coefficient. The value of CD is determined by the Reynold’s number (Re), with an increase in Re leading to CD reduction [74]. The Re determines the flow regime and is expressed as;

| (3) |

where; u and μ denote relative velocity and water viscosity, respectively [75].

Thus, it can be inferred that increased velocity will be obtained under conditions of increased volume or diameter of the particle [76]. The same principle may act as the driving force for virus removal from wastewater. As the viruses attach to suspended solids, the overall agglomerated particle possesses a larger diameter and higher density, thereby enhancing sedimentation and subsequent virus removal.

Further, the conventional activated sludge process was reported to achieve 0.65–2.85 LRV for eleven different kinds of viruses [77]. Likewise, a 1.4–1.7 LRV was accomplished for enteroviruses, rotaviruses, and noroviruses during the settling phase of wastewater in the treatment units [78]. The above studies suggested sedimentation as the prime mechanism for reduction of viral titres in the wastewater. On the contrary, it has been demonstrated that sedimentation is not the foremost removal mechanism [79,80], and only selected strains of norovirus and rotavirus get removed by sedimentation in the treatment plant. Hence, based on the present state-of-the-art, the sedimentation-based approach seems to be inadequate for the complete removal of viruses from the wastewater.

3.1.2. Sand and membrane-based filtration

The widely studied filtration processes for virus removal are the membrane and sand filtration, especially the technique of SSF [81]. The SSF holds great potential for the treatment of drinking water, rainwater, and wastewater. Further, various viral and bacterial pathogens like Escherichia virus MS2, Echovirus, PRD-1 virus, Salmonella sp., E.coli, and Streptococci sp., have been reported to be efficiently removed by the SSF process [82,83].

Another common technique called membrane filtration employs the size exclusion principle to achieve virus removal. The throughput of the membrane filtration system is defined by the system flux (flow of filtrate per unit area), represented as;

| (4) |

where, J (m3 m−2hr-1), Qp (m3 sec-1), and Am (m2) represent the flux, filtrate flow, and membrane surface area, respectively [84].

3.1.3. Ultraviolet disinfection

The widely used disinfection processes include UV radiation and chlorination. The demand for an additional dechlorination step after chlorination favours the use of UV radiation over chlorination for disinfection. The wastewater is exposed to a UV-C (100 nm – 280 nm) lamp, which is significantly effective against enteric protozoans, including Giardia sp., Cryptosporidium sp., and the bacterial pathogens [85]. Besides these pathogens, UV-C has been reported to be effective for the inactivation of various viruses, including SARS-CoV-2 [86]. The exposure of viruses to UV radiations results in nucleotide cross-linking in the viral genome, thereby causing viral inactivation [87,88]. The efficient and rapid inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 by DUV-LED has been recently reported by Inagaki et al. [89] where a DUV-LED of 280 ± 5 nm was observed to achieve an 87.4 % reduction in the infectious viral titre within 1 s and 99.9 % reduction within 10 s of UV irradiation. Another study reported the inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 by monochromatic UV-C (254 nm) irradiation and involved different illumination doses (3.7, 16.9 and 84.4 mJ cm−2) against a range of viral titres (0.05, 5 and 1000 multiplicity of infection) [86]. It was observed that a UV-C amount of only 3.7 mJ cm−2 resulted in a 3-log inactivation for viral load. Further, a UV-C dose of 16.9 mJ cm−2 was observed to achieve complete inhibition for all the viral titres [86].

The UV disinfection is associated with various advantages. For instance, the process requires a short contact time without the formation of any disinfection by-products. Also, UV radiation is relatively safer than the handling of chlorine gas or other chlorine derivatives [90]. However, the use of UV radiation is limited by high infrastructure costs and energy-intensive processes [91].

3.1.4. Photocatalytic membrane reactors

The PMRs have gained attention for wastewater disinfection. The PMR, which is defined as a combination of photocatalysis and a membrane process, has emerged as the most promising technology for the efficient removal of wastewater pathogens [92]. The virus removal efficiency of this hybrid reactor was studied by using bacteriophage P22 as a model virus by Guo et al. [93]. A LRV of 5.0 ± 0.7 was obtained for bacteriophage P22 in the presence of PMRs [93]. The removal of bacteriophage f2 by an integrated PMR system was also investigated [94]. An LRV of 5 was achieved with 24 h of continuous operation of the PMR system. It was concluded that the primary inactivation of phage occurred in the photolysis phase, while the membrane attributed mainly to the separation of virus particles. The study demonstrated that PMR could act as a promising technique for efficient virus removal. However, challenges of membrane stability, high capital, and operational costs demand more research [95].

Based on the present discussion, it is evident that filtration is efficient to some extent for the removal of viruses from wastewater. However, the physical methods (filtration, sedimentation) are focussed only on the separation of virus particles. Thus, the pathogens do not get inactivated and remain active for further infection. Further, the method of UV disinfection is limited by a lack of residual disinfection capacity and entails high energy and infrastructure costs. Also, the removal efficiency is highly governed by virus size, other wastewater chemicals, and the operational parameters.

3.2. Chemical treatment methods

In this approach, various chemicals are utilised for the removal of viruses from wastewater, and these are often employed along with other physical and biological processes. Two steps, namely disinfection involving the use of chemicals such as chlorine, chlorine dioxide, ozone, chloramine, detergents, alcohols [12], followed by dechlorination, constitute the chemical process of virus removal [96,97]. The use of the chemical approach is delimited by various drawbacks like the formation of carcinogenic disinfection by-products that demand additional treatment. The dechlorination process utilises various reducing agents (sodium sulphite, sodium bisulphite or sodium thiosulphate) for the removal of free/combined forms of chlorine residues from the wastewater effluent [98]. Also, certain enteric viruses and adenoviruses demonstrate high resistance to disinfection agents [13]. The coronaviruses also demonstrate a high sensitivity towards chlorine [99], thereby signifying the possible inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 by chlorination. Additionally, the ozone treatment has also been discussed to achieve efficient inactivation of viruses [100]. The higher levels of ozone, high temperature, and lower RH were reported to have a negative impact on the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. An increase in the ambient ozone concentration from 48.83 to 94.67 μg m−3, temperature from −13.17 °C–19 °C and a decrease in RH from 23.33 to 82.67% was associated with a reduced spread of SARS-CoV-2 infections [101].

However, the chemical treatment processes are associated with environmental toxicity and increased safety regulations for the handling and storage of chemicals. More cost and time are incurred due to additional dechlorination step, such as in the case of chlorination. Further, the virus removal efficiency of these methods is highly dependent upon the structure and genetic composition of the virus. Thus, alternative disinfection methods are required for the efficient removal of pathogens from wastewater.

3.3. Biological treatment methods

The biological treatment methods rely on the cellular activity of the microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, or algae) to achieve oxidation of organic matter present in the wastewater under aerobic or anaerobic conditions [102]. It includes bioelectrochemical systems, conventional activated sludge, aerated lagoons, oxidation ponds, membrane bioreactors, moving bed biofilm reactors, rotating biological contactors, trickling filters, and anaerobic digesters [103]. Since most studies for virus removal are focussed on granular reactors and membrane bioreactors, hence, the present study is limited to an account of sequencing batch biofilter granular reactors and membrane bioreactors for removal of viruses from wastewater.

3.3.1. Sequencing batch biofilter granular reactors

De Sanctis et al. [104] developed a simplified treatment scheme for the removal of pollutants and pathogens from municipal wastewater to produce safe treated water. The pilot-scale study was based on SBBGR, further enhanced by the sand filtration technique. Since the study aimed at providing treated water for reuse in agriculture, the microbiological quality of treated effluent was considered as the most crucial parameter. The quality was evaluated by monitoring the putative pathogens, namely Salmonella sp., Giardia lamblia, E.coli, Clostridium perfringens, Cryptosporidium parvum, adenovirus, enterovirus, and somatic coliphages. A substantial 3 LRV was obtained for the somatic coliphages while 2–3 LRV for adenovirus and enterovirus. Also, a 4 LRV, 3 LRV, and 1 LRV were achieved for E.coli, G.lamblia, and C.perfringens, respectively, along with the complete removal of Salmonella sp. and C.parvum by the SBBGR.

3.3.2. Membrane bioreactor

Membrane bioreactor, a combination of a membrane-based filtration process and a suspended growth biological reactor, is a useful alternative to achieve the removal of viruses from wastewater [105]. The MBR technology has gained attention due to features like the high quality of effluent and lower environmental footprint [106]. The process of size exclusion has been mentioned as the primary mechanism in MBR for the removal of pathogenic bacteria, while the virus removal mechanism is poorly understood. Some studies have emphasised the role of MLSS and backwashed membrane in virus inactivation [107,108] while the other mechanisms described are attachment to solids, enzymatic breakdown, interruption by membrane and cake layer and, predation [109]. A 6.3 LRV, 4.8 LRV, and 6.8 LRV were achieved for adenoviruses, noroviruses, and enteroviruses, respectively, in MBR [71]. Whereas, Kyria Da Silva et al. [110] reported 5.2–5.5 LRV of norovirus in MBR. In contrast, a study by Zhou et al. [78] concluded that the absolute removal of various viruses, including enteroviruses, noroviruses, and rotaviruses, could not be achieved by the MBR.

As evident, conflicting results are obtained for the utilisation of MBR for virus reduction. Also, the system is focussed mainly on physical separation while the removal is highly governed by virus structure, MLSS concentration, solids retention time, hydraulic retention time, and the system demands frequent membrane cleaning to achieve efficient removal. Further, the MBR is associated with other drawbacks like higher operation cost, energy-intensive process, and appropriate disposal of produced virus-contaminated sludge. These limitations may be overcome with the microalgae-based processes alone or coupled with the membrane technologies to produce a virologically safe treated water [21].

4. Microalgae-based approaches; an underexplored biological treatment method

In view of the above literature, it has become evident that various pathogenic viruses are abundant in the wastewater and linked with significant disease outbreaks. Also, the conventional approaches for pathogen removal are associated with various drawbacks; thus, the scientific community is now shifting its focus towards alternative treatment approaches [111]. The concept of phycoremediation; involving the use of microalgae or macroalgae for the removal of pollutants from wastewater, has been gaining impetuous attention [112].

The microalgae have recently been utilised for the removal of viruses from the wastewater [21,113,114]. Various studies have investigated the cultivation of microalgae in photobioreactors, biofilm reactors, MBRs, and oxidation ponds to evaluate their efficiencies for wastewater disinfection. A microalgae-based wastewater treatment system employing the extremophile Galdieria sulphuraria has been demonstrated to achieve high removal rates for enteroviruses (1.05 ± 0.32), noroviruses (1.49 ± 0.16) and coliphages (1.23 ± 0.343–3.13 ± 0.34) [16]. A team of researchers in Bangladesh developed a Pithophora sp. based sustainable and scalable filter paper for point-of-use purification of drinking water [115]. All types of infectious viruses and bacteria were demonstrated to be removed from the water by Pithophora cellulose filter paper. The surrogate latex nanobeads, in vitro model viruses, and real-life water samples were utilised to validate the performance of the filter paper. A simulated wastewater matrix with surrogate latex nanoparticles at a concentration of 1014 L−1 was prepared to evaluate its filtration properties. The latex nanobeads assay was followed by a SEM analysis of the filter paper before and after the filtration process. The removal study employed PR772 coliphage as large-size model viruses and MS2, ΦX174 as small-size model viruses. The developed filter paper achieved a LRV of more than 4 for all model viruses under different overhead pressures (1, 3 and 5 bar). The high pathogen load of the real-life wastewater samples was also effectively reduced by filter paper. Finally, it was concluded that 3 l of microbiologically safe drinking water could be produced within 25 min by using Pithophora filter paper (300 mm) at moderate overhead pressures. The study could help provide a solution to the lack of access to clean drinking water in Bangladesh and other countries.

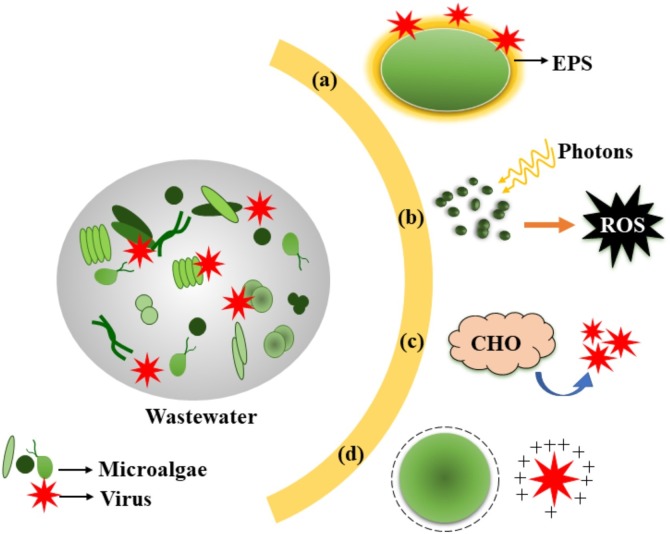

The mechanisms underlying microalgae-mediated virus inactivation has also been elucidated [21] and broadly classified as (i) sunlight-mediated inactivation, (ii) pH shift, (iii) adsorption, (iv) predation (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Graphical illustration of possible modes of microalgae-mediated virus inactivation, (a): EPS entrapment; (b): Sunlight-mediated inactivation (exogenous mode of indirect mechanism); (c) Toxic algal exudates; (d): Electrostatic attraction; (Abbreviations: EPS, exopolysaccharide; ROS, reactive oxygen species).

4.1. Sunlight-mediated inactivation

The microalgae are defined as photosynthetic organisms which utilise sunlight (as an energy source) or other carbon sources (in case of heterotrophs) and carbon dioxide to produce water and oxygen [116]. Various additional benefits are procured by utilisation of these sunlight driven biochemical factories in the wastewater treatment systems. The autotrophic or photoheterotrophic microalgae are cultivated in outdoor conditions, and thus, the sunlight driven microalgal growth governs the treatment efficiency. The presence of appropriate irradiance has been linked with an increase in the growth rate with subsequent production of higher microalgal biomass [117], thereby enhancing virus removal. Likewise, the sunlight also plays a crucial role in removal by directly targeting the viral pathogens. The sunlight-mediated mechanism for virus inactivation has been studied and classified as direct (UV-B) and indirect (UV-A) mechanism (Fig. 2b). The adsorption of photons by the virus, followed by damage of the viral capsid and genomic proteins constitute the direct mechanism while the indirect mechanisms are governed by the sensitizer molecules [19].

Depending upon the source of the sensitizers, the indirect mechanism is further categorised as endogenous (part of virus structure) and exogenous (in solution) processes. The endogenous mechanism of indirect inactivation involves the interaction between photons and amino acid chromophores in proteins of viral capsids [118]. On the other hand, various microalgal particulates and natural organic matter present in the wastewater treatment systems interact with the photons in the exogenous mode of indirect mechanism [119] Thus, the interaction of photosensitizer molecules and photons results in the formation of reactive radicals and intermediates that lead to the destruction of the viruses.

4.2. pH shift towards alkaline/acidic conditions

The microalgal cultivation in wastewater shifts the pH level, resulting in an alkaline/acidic environment. The microalgae-mediated elevation of dissolved oxygen and alkaline pH have been observed to be detrimental to various pathogens present in the wastewater, particularly; the faecal coliforms [120,121]. Alternatively, the cultivation of acidophilic microalgae like Galdieria sulphuraria leads to a shift in wastewater pH towards acidity. The low pH of 4 has been considered as the chief cause for the inactivation of E.coli in the Galdieria sulphuraria-based wastewater treatment system [122]. The pH inactivation can be further enhanced by extreme temperatures and sunlight-mediated inactivation in the wastewater treatment plants [13]. The pH variations during the light and dark cycle have also been found to contribute to bacterial reductions in wastewater [122]. Thus, it may be hypothesised that the shift of wastewater pH towards alkaline/acidic conditions may also play a role in virus inactivation by changing the overall charge of the virus, impacting the structural proteins, and enhancing the adsorption process.

4.3. Adsorption to the microalgal biomass

The removal of viruses from wastewater by adsorption onto the microalgal biomass, followed by sedimentation, is considered as one of the removal mechanisms. The attachment of viruses may be mediated by electrostatic interactions or the microalgal EPS (Fig. 2a, 2d). The surface properties of microalgae and virus cells govern the adsorption efficiency. This interaction can be further influenced by the surface charge on the capsid of the virus particles. The ionization state of the carboxyl and amino groups present in capsid proteins is largely dependent on the pH of the wastewater, thereby imparting an electrical charge to the virus [17]. Alternately, the microalgae are also reported to possess a net negative charge (-7.5 to −40 mV) at the pH levels commonly prevalent in wastewater treatment plants [20,123]. These interactions may lead to aggregation of virus particles onto microalgal cells, which can be further removed by the sedimentation process. Further, the production of cell-bound EPS by microalgae may enhance the adsorption of virus particles by entrapping them in the EPS matrix [19].

4.4. Predation; role of higher trophic level organisms

The microalgae-mediated virus inactivation may be influenced by the predation of viruses by organisms of higher trophic levels present in the ecosystem [20]. The presence of heterotrophic nanoflagellates and ciliates in the wastewater systems has been found to be associated with a reduction in virus viability [124,125]. A reduction in the abundance of virus-like particles was attributed to the feeding patterns of nanoflagellates in a eutrophic freshwater reservoir in Japan [126]. Contrary to this, nanoflagellates in another eutrophic lake in France were observed to achieve less than 1% removal of virus-like particles [127]. Also, the internalization of enteric viruses by protozoa can have both beneficial and detrimental impacts on the viruses. It may lead to virus reduction in wastewater or could help protect the viruses from various inactivation processes, thereby further contributing to the waterborne transmission of the pathogenic viral particles [128]. Further, microalgae also serve as the base of aquatic food webs and fed upon by various predators like zooplanktons and protozoa; particularly the rotifers, copepods, and ciliates [129]. The predation of microalgae may aid in the removal of viruses which are trapped onto the microalgal EPS or adhered by the electrostatic interactions. Alternatively, the death of virus or microalgal predators and their subsequent settlement to the bottom of the water system by sedimentation may also contribute to a reduction in virus numbers from wastewater.

5. Conclusion and future recommendations

There has been a substantial increase in evidence that reveals the presence of pathogenic viruses in the wastewater and/or treatment plants, including the novel coronavirus. The accurate detection and removal of these viruses would help to prevent the spread of the viral disease while producing a safe treated water for reuse. Thus, the efficiency of various treatment approaches is now being explored to combat viral disease outbreaks. This study highlights the inconsistency in the virus removal efficiency of various physical, chemical, and biological processes. Further, in view of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic; understanding the fate of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater treatment plants has emerged as a matter of utmost significance. Additionally, the microalgae-based approach (a biological method) could serve as an alternative to the prevalent energy-intensive and expensive disinfection techniques. The utilisation of microalgal processes, in combination with the natural temperature, pH, or light conditions prevalent in the treatment systems, may facilitate the complete removal of viruses from wastewater. Moreover, extensive research and evaluation are warranted to establish the economic feasibility of phycoremediation-based methods on a commercial scale.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Editor: Z. Wen

References

- 1.Malik A., Yasar A., Tabinda A.B., Abubakar M. Water-borne diseases, cost of illness and willingness to pay for diseases interventions in rural communities of developing countries. Iran. J. Public Health. 2012;41:39–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xagoraraki I., O’Brien E. Springer, Cham; 2020. Wastewater-Based Epidemiology for Early Detection of Viral Outbreaks; pp. 75–97. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tripathi B. 2018. Diarrhoea Took More Lives Than Any Other Water-Borne Disease In India.https://www.indiaspend.com/diarrhoea-took-more-lives-than-any-other-water-borne-disease-in-india-58143/ (accessed April 28, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao X. COVID-19: immunopathology and its implications for therapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:269–270. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0308-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeo C., Kaushal S., Yeo D. Enteric involvement of coronaviruses: is faecal–oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 possible? Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30048-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallapaty S. How sewage could reveal true scale of coronavirus outbreak. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lodder W., de Roda Husman A.M. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: potential health risk, but also data source. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5(6):533–534. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30087-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed W., Angel N., Edson J., Bibby K., Bivins A., O’Brien J.W., Choi P.M., Kitajima M., Simpson S.L., Li J., Tscharke B., Verhagen R., Smith W.J.M., Zaugg J., Dierens L., Hugenholtz P., Thomas K.V., Mueller J.F. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:138764. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu F., Xiao A., Zhang J., Gu X., Lee W.L., Kauffman K., Hanage W., Matus M., Ghaeli N., Endo N., Duvallet C., Moniz K., Erickson T., Chai P., Thompson J., Alm E. SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater are higher than expected from clinically confirmed cases. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.05.20051540. 2020.04.05.20051540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antony A., Blackbeard J., Leslie G. Removal efficiency and integrity monitoring techniques for virus removal by membrane processes. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;42:891–933. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2011.556539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlindwein A.D., Rigotto C., Simõ C.M.O., Barardi C.R.M. Detection of enteric viruses in sewage sludge and treated wastewater effluent. Water Sci. Technol. 2010;61:537–544. doi: 10.2166/wst.2010.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang C.M., Xu L.M., Xu P.C., Wang X.C. Elimination of viruses from domestic wastewater: requirements and technologies. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;32:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dar R., Sharma N., Kaur K., Phutela U. Appl. Microalgae Wastewater Treat. Springer, Cham; 2019. Feasibility of microalgal technologies in pathogen removal from wastewater; pp. 237–268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foladori P., Cutrupi F., Segata N., Manara S., Pinto F., Malpei F., Bruni L., La Rosa G. SARS-CoV-2 from faeces to wastewater treatment: What do we know? A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;743:140444. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rizwan M., Mujtaba G., Memon S.A., Lee K., Rashid N. Exploring the potential of microalgae for new biotechnology applications and beyond: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018;92:394–404. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delanka-Pedige H.M.K., Cheng X., Munasinghe-Arachchige S.P., Abeysiriwardana-Arachchige I.S.A., Xu J., Nirmalakhandan N., Zhang Y. Metagenomic insights into virus removal performance of an algal-based wastewater treatment system utilizing Galdieria sulphuraria. Algal Res. 2020;47:101865. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2020.101865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Templeton M.R., Andrews R.C., Hofmann R. Particle-associated viruses in water: impacts on disinfection processes. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;38:137–164. doi: 10.1080/10643380601174764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delanka-Pedige H.M.K., Munasinghe-Arachchige S.P., Cornelius J., Henkanatte-Gedera S.M., Tchinda D., Zhang Y., Nirmalakhandan N. Pathogen reduction in an algal-based wastewater treatment system employing Galdieria sulphuraria. Algal Res. 2019;39:101423. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2019.101423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rains J.D. 2016. Removal of Pathogenic Bacteria in Algal Turf Scrubbers. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verbyla M.E., Mihelcic J.R. A review of virus removal in wastewater treatment pond systems. Water Res. 2015;71:107–124. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delanka-Pedige H.M.K., Munasinghe-Arachchige S.P., Zhang Y., Nirmalakhandan N. Bacteria and virus reduction in secondary treatment: potential for minimizing post disinfectant demand. Water Res. 2020:115802. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosario K., Morrison C.M., Mettel K.A., Betancourt W.Q. Novel circular rep-encoding single-stranded DNA viruses detected in treated wastewater. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2019 doi: 10.1128/MRA.00318-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chatterjee A., Sicheritz-Pontén T., Yadav R., Kondabagil K. Genomic and metagenomic signatures of giant viruses are ubiquitous in water samples from sewage, inland lake, waste water treatment plant, and municipal water supply in Mumbai, India. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40171-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prevost B., Lucas F.S., Goncalves A., Richard F., Moulin L., Wurtzer S. Large scale survey of enteric viruses in river and waste water underlines the health status of the local population. Environ. Int. 2015;79:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R., Brouwer A. Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 RNA in sewage and correlation with reported COVID-19 prevalence in the early stage of the epidemic in the Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7:511–516. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Guyader F.S., Mittelholzer C., Haugarreau L., Hedlund K.O., Alsterlund R., Pommepuy M., Svensson L. Detection of noroviruses in raspberries associated with a gastroenteritis outbreak. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004;97:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richards G.P. Enteric virus contamination of foods through industrial practices: a primer on intervention strategies. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001;27(2):117–125. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris L.J., Farber J.N., Beuchat L.R., Parish M.E., Suslow T.V., Garrett E.H., Busta F.F. Outbreaks associated with fresh produce: incidence, growth, and survival of pathogens in fresh and fresh-cut produce. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2003;2:78–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sincero T.C.M., Levin D.B., Simões C.M.O., Barardi C.R.M. Detection of hepatitis A virus (HAV) in oysters (Crassostrea gigas) Water Res. 2006;40:895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okoh A.I., Sibanda T., Gusha S.S. Inadequately treated wastewater as a source of human enteric viruses in the environment. Open Access Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2010;7:7. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7062620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rehnstam-Holm A.S., Hernroth B. Shellfish and public health: a Swedish perspective. Ambio. 2005;34:139–144. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-34.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cascella M., Rajnik M., Cuomo A., Dulebohn S.C., Di Napoli R. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jalava K. First respiratory transmitted food borne outbreak? Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2020;226:113490. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Heal. Organ; 2020. WHO, Water, Sanitation, Hygiene and Waste Management for the COVID-19 Virus; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Y., Guo C., Tang L., Hong Z., Zhou J., Dong X., Yin H., Xiao Q., Tang Y., Qu X., Kuang L., Fang X., Mishra N., Lu J., Shan H., Jiang G., Huang X. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5(5):434–435. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang T., Cui X., Zhao X., Wang J., Zheng J., Zheng G., Guo W., Cai C., He S., Xu Y. Detectable SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in feces of three children during recovery period of COVID-19 pneumonia. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R., Lu R., Han K., Wu G., Tan W. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323:1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qu G., Li X., Hu L., Jiang G. An imperative need for research on the role of environmental factors in transmission of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:3732. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c01102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weber D.J., Rutala W.A., Fischer W.A., Kanamori H., Sickbert-Bennett E.E. Emerging infectious diseases: focus on infection control issues for novel coronaviruses (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-CoV and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-CoV), hemorrhagic fever viruses (Lassa and Ebola), and highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses, A(H5N1) and A(H7N9) Am. J. Infect. Control. 2016;44:e91–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mao K., Zhang H., Yang Z. Can a Paper-Based Device Trace COVID-19 Sources with Wastewater-Based Epidemiology? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:3735. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c01174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lesté-Lasserre C. Coronavirus found in Paris sewage points to early warning system. Science. 2020;368:6489. doi: 10.1126/science.abc3799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gall A.M., Mariñas B.J., Lu Y., Shisler J.L. Waterborne Viruses: A Barrier to Safe Drinking Water. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang C., Li Y., Shuai D., Shen Y., Wang D. Progress and challenges in photocatalytic disinfection of waterborne Viruses: a review to fill current knowledge gaps. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;355:399–415. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.08.158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maunula L., Klemola P., Kauppinen A., Söderberg K., Nguyen T., Pitkänen T., Kaijalainen S., Simonen M.L., Miettinen I.T., Lappalainen M., Laine J., Vuento R., Kuusi M., Roivainen M. Enteric viruses in a large waterborne outbreak of acute gastroenteritis in Finland. Food Environ. Virol. 2009;1(1):31–36. doi: 10.1007/s12560-008-9004-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chitambar S.D., Joshi M.S., Sreenivasan M.A., Arankalle V.A. Fecal shedding of hepatitis A virus in Indian patients with hepatitis A and in experimentally infected Rhesus monkey. Hepatol. Res. 2001;19:237–246. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6346(00)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masclaux F.G., Hotz P., Friedli D., Savova-Bianchi D., Oppliger A. High occurrence of hepatitis E virus in samples from wastewater treatment plants in Switzerland and comparison with other enteric viruses. Water Res. 2013;47:5101–5109. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mukhopadhya I., Sarkar R., Menon V.K., Babji S., Paul A., Rajendran P., Sowmyanarayanan T.V., Moses P.D., Iturriza-Gomara M., Gray J.J., Kang G. Rotavirus shedding in symptomatic and asymptomatic children using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. J. Med. Virol. 2013;85:1661–1668. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martínez M.A., De M., Soto-Del Río D., María Gutiérrez R., Chiu C.Y., Greninger A.L., Contreras J.F., López S., Arias C.F., Isa P. DNA microarray for detection of gastrointestinal viruses. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01317-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mori K., Hayashi Y., Akiba T., Nagano M., Tanaka T., Hosaka M., Nakama A., Kai A., Saito K., Shirasawa H. Multiplex real-time PCR assays for the detection of group C rotavirus, astrovirus, and Subgenus F adenovirus in stool specimens. J. Virol. Methods. 2013;191(2):141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hata A., Kitajima M., Katayama H. Occurrence and reduction of human viruses, F-specific RNA coliphage genogroups and microbial indicators at a full-scale wastewater treatment plant in Japan. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013;114:545–554. doi: 10.1111/jam.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ganesh A., Lin J. Waterborne human pathogenic viruses of public health concern. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2013;23:544–564. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2013.769205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berciaud S., Rayne F., Kassab S., Jubert C., Faure-Della Corte M., Salin F., Wodrich H., Lafon M.E., Barat P., Fayon M., Fleury H., Lamireau T., Llanas B., Milpied N., Perel Y., Pillet P., Sarlangue J., Tabrizi R., Vérité C., Vigouroux S. Adenovirus infections in Bordeaux University Hospital 2008-2010: clinical and virological features. J. Clin. Virol. 2012;54:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeulin H., Salmon A., Bordigoni P., Venard V. Diagnostic value of quantitative PCR for adenovirus detection in stool samples as compared with antigen detection and cell culture in haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011;17:1674–1680. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haramoto E., Kitajima M., Otagiri M. Development of a reverse transcription-quantitative PCR assay for detection of Salivirus/Klassevirus. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1128/AEM.00132-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siebrasse E.A., Reyes A., Lim E.S., Zhao G., Mkakosya R.S., Manary M.J., Gordon J.I., Wang D. Identification of MW polyomavirus, a novel polyomavirus in human stool. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01210-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kelly T.R., Machalaba C., Karesh W.B., Crook P.Z., Gilardi K., Nziza J., Uhart M.M., Robles E.A., Saylors K., Joly D.O., Monagin C., Mangombo P.M., Kingebeni P.M., Kazwala R., Wolking D., Smith W., Mazet J.A.K. Implementing one Health approaches to confront emerging and re-emerging zoonotic disease threats: lessons from PREDICT. One Heal. Outlook. 2020;2:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s42522-019-0007-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mackenzie J.S., Smith D.W. COVID-19: a novel zoonotic disease caused by a coronavirus from China: what we know and what we don’t. Microbiol. Aust. 2020;41:45–50. doi: 10.1071/ma20013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin K., Marr L. Aerosolization of ebola virus surrogates in wastewater systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51(5):2669–2675. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b04846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou P., Lou Yang X., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.L., Chen H.D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Di Jiang R., Liu M.Q., Chen Y., Shen X.R., Wang X., Zheng X.S., Zhao K., Chen Q.J., Deng F., Liu L.L., Yan B., Zhan F.X., Wang Y.Y., Xiao G.F., Shi Z.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murphy H. Persistence of pathogens in sewage and other water types. Glob. Water Pathog. Proj. Part. 2017;4 doi: 10.14321/waterpathogens.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Araud E., DiCaprio E., Ma Y., Lou F., Gao Y., Kingsley D., Hughes J.H., Li J. Thermal inactivation of enteric viruses and bioaccumulation of enteric foodborne viruses in live oysters (Crassostrea virginica) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;82:2086–2099. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03573-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chan K.H., Peiris J.S.M., Lam S.Y., Poon L.L.M., Yuen K.Y., Seto W.H. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. Adv. Virol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/734690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pastorino B., Touret F., Gilles M., de Lamballerie X., Charrel R.N. Evaluation of heating and chemical protocols for inactivating SARS-CoV-2. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.11.036855. 2020.04.11.036855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chin A.W.H., Chu J.T.S., Perera M.R.A., Hui K.P.Y., Yen H.-L., Chan M.C.W., Peiris M., Poon L.L.M. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. The Lancet Microbe. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guillier L., Martin-Latil S., Chaix E., Thébault A., Pavio N., Le Poder S., Batéjat C., Biot F., Koch L., Schaffner D., Sanaa M. Modelling the inactivation of viruses from the Coronaviridae family in response to temperature and relative humidity in suspensions or surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/aem.01244-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Munster V. Stability of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) under different environmental conditions. Eurosurveillance. 2013;18:20590. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.38.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Crini G., Lichtfouse E. Advantages and disadvantages of techniques used for wastewater treatment. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019;17:145–155. doi: 10.1007/s10311-018-0785-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fu C.Y., Xie X., Huang J.J., Zhang T., Wu Q.Y., Chen J.N., Hu H.Y. Monitoring and evaluation of removal of pathogens at municipal wastewater treatment plants. Water Sci. Technol. 2010;61:1589–1599. doi: 10.2166/wst.2010.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prado T., de Castro Bruni A., Barbosa M.R.F., Garcia S.C., de Jesus Melo A.M., Sato M.I.Z. Performance of wastewater reclamation systems in enteric virus removal. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;678:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carducci A., Battistini R., Rovini E., Verani M. Viral removal by wastewater treatment: monitoring of indicators and pathogens. Food Environ. Virol. 2009;1:85–91. doi: 10.1007/s12560-009-9013-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simmons F., Kuo D., Xagoraraki I. Removal of human enteric viruses by a full-scale membrane bioreactor during municipal wastewater processing. Water Res. 2011;45(9):2739–2750. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Topare N.S., Attar S.J., Manfe M.M. SEWAGE/WASTEWATER TREATMENT TECHNOLOGIES: A REVIEW. Sci. Revs. Chem. Commun. 2011;1:18–24. www.sadgurupublications.com (accessed July 24, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shin G.A., Sobsey M.D. Removal of norovirus from water by coagulation, flocculation and sedimentation processes. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply. 2015;15:158–163. doi: 10.2166/ws.2014.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lizica-Simona P. Design of a primary clarifier for sedimentation process in a wastewater treatment plant. Analele Univ. Marit. Constanta. 2016;17(26):43–46. https://cmu-edu.eu/anale/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2017/09/Anale-vol-26-.pdf#page=43 (accessed May 14, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reynolds O. XXIX. An experimental investigation of the circumstances which determine whether the motion of water shall be direct or sinuous, and of the law of resistance in parallel channels. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. 1883;174:935–982. doi: 10.1098/rstl.1883.0029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mohammed M.A.R., Halagy D.A.E. Studying the factors affecting the settling velocity of solid particles in non-newtonian fluids. Al-Nahrain J. Eng. Sci. 2013;16:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kitajima M., Iker B.C., Pepper I.L., Gerba C.P. Relative abundance and treatment reduction of viruses during wastewater treatment processes - Identification of potential viral indicators. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;488–489:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou J., Wang X.C., Ji Z., Xu L., Yu Z. Source identification of bacterial and viral pathogens and their survival/fading in the process of wastewater treatment, reclamation, and environmental reuse. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;31:109–120. doi: 10.1007/s11274-014-1770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Da Silva A.K., Le Guyader F.S., Le Saux J.C., Pommepuy M., Montgomery M.A., Elimelech M. Norovirus removal and particle association in a waste stabilization pond. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:9151–9157. doi: 10.1021/es802787v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Symonds E.M., Verbyla M.E., Lukasik J.O., Kafle R.C., Breitbart M., Mihelcic J.R. A case study of enteric virus removal and insights into the associated risk of water reuse for two wastewater treatment pond systems in Bolivia. Water Res. 2014;65:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Verma S., Daverey A., Sharma A. Slow sand filtration for water and wastewater treatment–a review. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2017;6:47–58. doi: 10.1080/21622515.2016.1278278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Katukiza A., Ronteltap M., Niwagaba C., Kansiime F., PNL L. Grey water treatment in urban slums by a filtration system: optimisation of the filtration medium. J. Environ. Manage. 2014;146:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Elliott M., Stauber C., Koksal F., DiGiano F., Sobsey M. Reductions of E. coli, echovirus type 12 and bacteriophages in an intermittently operated household-scale slow sand filter. Water Res. 2008;42(10–11):2662–2670. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.USEPA . United States Environ. Prot. Agency; Washingt. DC: 2005. Membrane Filtration Guidance Manual EPA 815-R-06-009. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hijnen W.A.M., Beerendonk E.F., Medema G.J. Inactivation credit of UV radiation for viruses, bacteria and protozoan (oo)cysts in water: A review. Water Res. 2006;40:3–22. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bianco A., Biasin M., Pareschi G., Cavalieri A., Cavatorta C., Fenizia C., Galli P., Lessio L., Lualdi M., Redaelli E., Saulle I., Trabattoni D., Zanutta A., Clerici M. UV-C irradiation is highly effective in inactivating and inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 replication. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.05.20123463. 2020.06.05.20123463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Young S., Torrey J., Bachmann V., Kohn T. Relationship between inactivation and genome damage of human enteroviruses upon treatment by UV254, free chlorine, and ozone. Food Environ. Virol. 2020;12:20–27. doi: 10.1007/s12560-019-09411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barrett M., Fitzhenry K., O’Flaherty V., Dore W., Keaveney S., Cormican M., Rowan N., Clifford E. Detection, fate and inactivation of pathogenic norovirus employing settlement and UV treatment in wastewater treatment facilities. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;568:1026–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Inagaki H., Saito A., Sugiyama H., Okabayashi T., Fujimoto S. Rapid inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 with Deep-UV LED irradiation. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.06.138149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Collivignarelli M.C., Abbà A., Benigna I., Sorlini S., Torretta V. Overview of the main disinfection processes for wastewater and drinking water treatment plants. Sustain. 2018;10:86. doi: 10.3390/su10010086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Foteinis S., Borthwick A.G.L., Frontistis Z., Mantzavinos D., Chatzisymeon E. Environmental sustainability of light-driven processes for wastewater treatment applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;182:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cheng R., Shen L., Wang Q., Xiang S., Shi L., Zheng X., Lv W. Photocatalytic membrane reactor (PMR) for virus removal in drinking water: effect of humic acid. Catalysts. 2018;8:284. doi: 10.3390/catal8070284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guo B., Pasco E.V., Xagoraraki I., Tarabara V.V. Virus removal and inactivation in a hybrid microfiltration-UV process with a photocatalytic membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015;149:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2015.05.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zheng X., Wang Q., Chen L., Wang J., Cheng R. Photocatalytic membrane reactor (PMR) for virus removal in water: performance and mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2015;277:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2015.04.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zheng X., Shen Z.-P., Shi L., Cheng R., Yuan D.-H. Photocatalytic membrane reactors (PMRs) in water treatment: configurations and influencing factors. Catalysts. 2017;7(8):224. doi: 10.3390/catal7080224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Montemayor M., Costan A., Lucena F., Jofre J., Muñoz J., Dalmau E., Mujeriego R., Sala L. The combined performance of UV light and chlorine during reclaimed water disinfection. Water Sci. Technol. 2008;57:935–940. doi: 10.2166/wst.2008.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wigginton K., Kohn T. Virus disinfection mechanisms: the role of virus composition, structure, and function. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2(1):84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.11.003. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1879625711001684?casa_token=dhAKXnzQImYAAAAA:mA0Eu1r5YnwpHzG-o2oR_kCRDUmCbjEX9RzUE-NCjPrPWGlXtvpFECyzCQVwrt6Hdi5N5Fi5tx8 (accessed April 19, 2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pan L., Zhang X., Yang M., Han J., Jiang J., Li W., Yang B., Li X. Effects of dechlorination conditions on the developmental toxicity of a chlorinated saline primary sewage effluent: Excessive dechlorination is better than not enough. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;692:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Romano-Bertrand S., Aho Glele L.-S., Grandbastien B., Lepelletier D. Preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission in rehabilitation pools and therapeutic water environments. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020;105:625–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.García de Abajo F.J., Hernández R.J., Kaminer I., Meyerhans A., Rosell-Llompart J., Sanchez-Elsner T. Back to normal: an old physics route to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission in indoor spaces. ACS Nano. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c04596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yao M., Zhang L., Ma J., Zhou L. On airborne transmission and control of SARS-Cov-2. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;731:139178. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Samer M. Wastewater Treat. Eng. InTech; 2015. Biological and chemical wastewater treatment processes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Krzeminski P., Tomei M.C., Karaolia P., Langenhoff A., Almeida C.M.R., Felis E., Gritten F., Andersen H.R., Fernandes T., Manaia C.M., Rizzo L., Fatta-Kassinos D. Performance of secondary wastewater treatment methods for the removal of contaminants of emerging concern implicated in crop uptake and antibiotic resistance spread: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;648:1052–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.De Sanctis M., Del Moro G., Chimienti S., Ritelli P., Levantesi C., Di Iaconi C. Removal of pollutants and pathogens by a simplified treatment scheme for municipal wastewater reuse in agriculture. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;580:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Marti E., Monclús H., Jofre J., Rodriguez-Roda I., Comas J., Balcázar J.L. Removal of microbial indicators from municipal wastewater by a membrane bioreactor (MBR) Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102:5004–5009. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Xiao K., Liang S., Wang X., Chen C., Huang X. Current state and challenges of full-scale membrane bioreactor applications: a critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2019;271:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xagoraraki I., Yin Z., Svambayev Z. Fate of viruses in water systems. J. Environ. Eng. New York (New York) 2014;140:04014020. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)EE.1943-7870.0000827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Miura T., Okabe S., Nakahara Y., Sano D. Removal properties of human enteric viruses in a pilot-scale membrane bioreactor (MBR) process. Water Res. 2015;75:282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chaudhry R.M., Nelson K.L., Drewes J.E. Mechanisms of pathogenic virus removal in a full-scale membrane bioreactor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:2815–2822. doi: 10.1021/es505332n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kyria Da Silva A., Le Saux J.-C., Parnaudeau S., Pommepuy M., Elimelech M., Le Guyader F.S. Evaluation of Removal of Noroviruses during Wastewater Treatment, Using Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR: Different Behaviors of Genogroups I and II. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:7891–7897. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01428-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Prajapati S.K., Kaushik P., Malik A., Vijay V.K. Phycoremediation coupled production of algal biomass, harvesting and anaerobic digestion: possibilities and challenges. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013;31:1408–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Prajapati S.K., Choudhary P., Malik A., Vijay V.K. Algae mediated treatment and bioenergy generation process for handling liquid and solid waste from dairy cattle farm. Bioresour. Technol. 2014;167:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]