Abstract

Background

The role of two recently identified polyomaviruses, KI and WU, in the causation of respiratory disease has not been established.

Objectives

To determine the prevalence of KI and WU viruses (KIV and WUV) in 371 respiratory samples and evaluate their contribution to respiratory disease.

Study Design

Specimens were screened for KIV and WUV using single, multiplex or real time PCR; co-infection with other respiratory viruses was evaluated.

Results

Of the 371 samples analysed, 10 (2.70%) were positive for KIV and 4 (1.08%) were positive for WUV yielding an overall case prevalence of KIV and WUV infection of 3.77%. KIV and WUV were identified in patients aged <15 years (11 patients) with upper or lower respiratory tract infection and >45 years (3 patients) with upper respiratory tract infection. Co-infections were found in 5 (50%) and 3 (75%) of the KIV and WUV positive samples, respectively.

Conclusions

This study supports previous conclusions that KIV and WUV detection in the respiratory tract may be coincidental and reflect reactivation of latent or persistent infection with these viruses. The age distribution of KIV and WUV infection in this study mirrors that found for the other human polyomaviruses, BK and JC.

Keywords: Human polyomavirus, KI, WU, Respiratory infection, PCR, Co-infection

1. Introduction

In 2007, two new human viruses, KI and WU, were identified in respiratory tract specimens. Phylogenetic analyses of the complete genome of these viruses revealed them to be polyomaviruses.1, 2

In the first descriptions of these viruses KIV DNA was detected in 6 (1%) of 637 nasopharyngeal aspirates of Swedish patients 1 and WU virus infection was found with a prevalence of 3.0% in respiratory samples in Brisbane, Australia and 0.7% in St. Louis, USA.2 Subsequent molecular studies reported incidences of 2.5% (Australia) 3 and 1.5% (Scotland) 4 for KIV and 7% (South Korea),5 0.4% (China),6 4.9% (Germany),7 2.5% (Canada),8 and 2.7% (St. Louis, Missouri, USA) 9 for WUV suggesting worldwide distribution of these viruses. KI and WU polyomaviruses have been mainly detected in nasopharyngeal aspirates from children and the presence of one or more additional respiratory viruses in the specimens appears to be common.

Some reports have suggested that detection of these viruses among very young children implies that KIV and WUV have an aetiological role in childhood respiratory diseases.2, 3, 10 An alternative proposal is that KIV and WUV are simply latent viruses that are reactivated during respiratory disease of other cause.4

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of KI and WU viruses in respiratory specimens collected from Manchester, UK and evaluate their contribution to respiratory disease alone or in combination with other respiratory viruses.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Specimens collection and processing

A total of 371 specimens from patients with respiratory tract disease were randomly selected from 1335 nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPA) collected by the Clinical Virology Laboratory, Manchester Royal Infirmary, between October 2006 and February 2007 and stored at −70 °C until use. Specimens were re-used for this study in accordance with current Royal College of Pathologists Guideline (G035) (www.rcpath.org/index.asp?PageID=38) on re-use of diagnostic specimens. Specimens and associated clinical data were collected; the specimens were anonymised by renumbering and removal of all patient identifiers from the data before use in this study.

2.2. Respiratory virus screening

All specimens were examined by multiplex RT-PCR for Influenza A, B, and C; real time PCR for bocavirus (hBoV) and parainfluenza viruses types 1–3; single RT-PCRs for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) types A and B, and human metapneumovirus (HMPV) (manuscript in preparation, Al-Hammadi et al.).

2.3. KI and WU PCR assays

Nucleic acid was extracted from nasopharyngeal aspirates using the QIAampDNA Blood BioRobot MDx Kit (Qiagen Ltd., West Sussex, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions and stored at −20 °C until use. Samples were analysed by PCR using POLVP1-39F and POLVP1-363R for KIV 1 and AG0044 and AG0045 for WUV2. KIV and WUV positive sample extracts were then subjected to a second PCR analysis using primers targeting an alternative region of the genome (POLVP1-118F and POLVP1-324R for KIV; AG0048 and AG0049 for WUV).1, 2

2.4. Sequencing

Sequencing was performed using the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems UK Ltd.) on the ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer. Contiguous sequences were assembled using Sequencher software version 4.6. To identify KIV and WUV specific sequences a Blast search (NCBI) was performed.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

The median age of the 371 patients was 8 months (mean 10 years; range 7 days–79 years), and the male to female ratio was 1.3:1 (213:158). The age distribution of the study population was as follows: 298 patients <15 years (80.32%), 26 patients 15–44 years (7.00%), 26 patients 45–60 years (7.00%) and 21 patients >60 years old (5.66%).

3.2. Prevalence of KIV and WUV

KIV and WUV DNA were detected in 10 (2.7%) and 4 (1.08%) respectively of the 371 nasopharyngeal specimens yielding an overall case prevalence of KIV and WUV infection of 3.77%. Sequence analysis of the KIV and WUV PCR products from both assays (VP1, VP2, and LT-Ag regions) revealed 99% homology with the published sequences of these viruses in GenBank (NCBI) (EF127906–EF127908 and EF444549–EF444554, respectively).

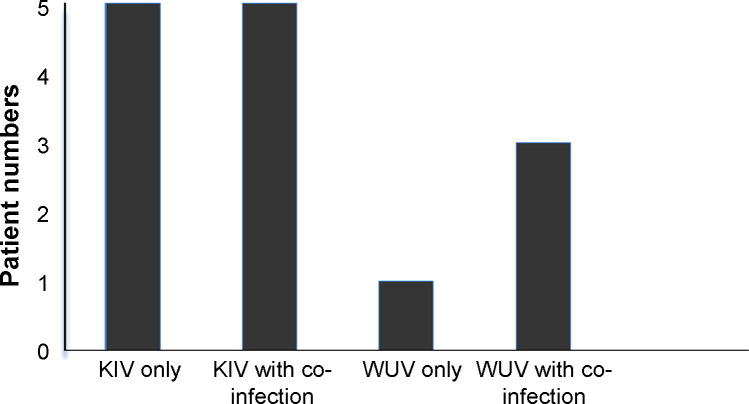

The co-detection of KIV and WUV with other respiratory viruses was found in 57.14% (n = 8 [5 KI/3 WU]) of cases (Fig. 1 ). Most common was HMPV (n = 4 [2 KI/2 WU]; 28.57%) followed by RSV-B (n = 1 [KI]; 7.14%), bocavirus (n = 1 [WU]; 7.14%) and parainfluenza virus type 1 (n = 1 [KI]; 7.14%). One KIV infected patient also had both RSV-B and bocavirus (7.14%).

Fig. 1.

Co-detection of KIV and WUV with other respiratory viruses.

3.3. Clinical findings associated with the presence of KIV and WUV infection

The age distribution of patients with KIV and WUV infection is shown in Table 1 . The 10 KIV-infected patients (5 males and 5 females; ratio: 1:1) had a median age of 10 months (mean 18.5 years; range 21 days–69 years). The male to female ratio of the WUV positive patients was 1:1 (2:2) and the median age of WUV positive patients was 9 months (mean 4 years; range 5 month–14 years). KIV and WUV infections were found in patients aged less than 15 years of age or 45 years and above. Three and a half percent of children in the youngest age group (0–5 years) were positive, and the figure rose to 6% at 6–14 years. This declined in the mid range years and thereafter rose to reach 9.52% at >60 years. KIV and WUV cases showed weekly variation over the study period but there was no evidence for a higher frequency of detection of these viruses in early winter.

Table 1.

Age distribution of KIV and WUV infected patients

| Age (years) | Samples tested | KIV positive no. (%) | WUV positive no. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 224 | 6(2.67) | 2(0.89) |

| 1–5 | 58 | 1(1.72) | 1(1.72) |

| 6–14 | 16 | 0(0) | 1(6.25) |

| 15–29 | 11 | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| 30–44 | 15 | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| 45–60 | 26 | 1(3.84) | 0(0) |

| >60 | 21 | 2(9.52) | 0(0) |

| Total | 371 | 10(2.7) | 4(1.08) |

4. Discussion

KIV and WUVDNA were found in 2.7% and 1.08%, respectively of NPAs obtained from patients with respiratory tract disease. The frequency of KIV and WUV detection in this study is similar to that found in some previous reports.1, 2, 3, 4, 6 A higher proportion of co-infections with KIV or WUV and other respiratory viruses is reported here. Further, as several other respiratory pathogens including rhinovirus, adenovirus, coronavirus and enterovirus were not tested in this study the proportion of co-infections is possibly even higher. These data agree with previous findings 4, 8, 9 suggesting that KIV and WUV infection may be incidental without a significant role in the causation of respiratory infections.

In the present study, KIV and WUV infected individuals were found in two main age groups: <15 years and >45 years. A relatively high proportion of KIV and WUV infections were observed in the oldest (>60 years) age group. Infection in patients <15 years was more frequently associated with lower respiratory tract symptoms. They also showed more frequent co-infections with other respiratory viruses. The older age group patients (>45 years old) were more likely to have symptoms associated with upper respiratory tract infection. Samples collected from patients whose age was >18 months tended to be patients undergoing solid organ or bone marrow transplantation, treatment of cancer (particularly leukaemia), or were hospitalised because of severe, life threatening, acute respiratory distress. These data suggest that infection with KIV and WUV occurs early in childhood. The viruses may then establish persistent infection possibly in the respiratory tract and become reactivated during respiratory disease of any cause. The age distribution of positive cases in this study presents a pattern of infection similar to that seen with JCV and BKV. Further studies of the seroprevalence of KIV and WUV in different age groups will shed light on this issue.

References

- 1.Allander T., Andreasson K., Gupta S., Bjerkner A., Bogdanovic G., Persson M.A. Identification of a third human polyomavirus. J Virol. 2007;81:4130–4136. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00028-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaynor A.M., Nissen M.D., Whiley D.M., Mackay I.M., Lambert S.B., Wu G. Identification of a novel polyomavirus from patients with acute respiratory tract infections. PLoS Pathogens. 2007;3:e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bialasiewicz S., Whiley D.M., Lambert S.B., Wang D., Nissen M.D., Sloots T.P. A newly reported human polyomavirus, KI virus, is present in the respiratory tract of Australian children. J Clin Virol. 2007;40:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norja P., Ubillos I., Templeton K., Simmonds P. No evidence for an association between infections with WU and KI polyomaviruses and respiratory disease. J Clin Virol. 2007;40:307–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han T.H., Chung J., Koo J.W., Kim S.W., Hwang E.S. WU polyomavirus in children with acute lower respiratory tract infections, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1766–1768. doi: 10.3201/eid1311.070872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin F., Zheng M., Li H., Zheng C., Li X., Rao G. WU polyomavirus in children with acute lower respiratory tract infections, China. J Clin. Virol. 2008;42:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neske F., Blessing K., Ullrich F., Prottel A., Wolfgang Kreth H., Weissbrich B. WU polyomavirus infection in children, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:680–681. doi: 10.3201/eid0104.071325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abed Y., Wang D., Boivin G. WU polyomavirus in children, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1939–1941. doi: 10.3201/eid1312.070909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le B-M., Demertzis L.M., Wu G., Tibbets R.J., Buller R., Arens M.Q. Clinical and epidemiological characterization of WU polyomavirus infection, St. Louis, Missouri. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1936–1938. doi: 10.3201/eid1312.070977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan X.H., Xu Z.Q., Xie ZP, Gao HC, Zhang R.F., Song J.R. WU polyomavirus and KI polyomavirus detected in specimens from children with acute respiratory tract infection in China. Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi. 2008;22:21–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]