Abstract

Adult croup is a distinct disease entity that probably represents a heterogeneous clinical syndrome. Three cases of adult laryngotracheitis characterized by upper airway infection and progression to airway obstruction are illustrated. Close observation and prompt decisions regarding airway intervention are critical in effective management, and complete resolution is expected.

Key Words: dault, rcoup, amnagement, tracheitis

For almost 60 years, laryngotracheobronchitis, or croup, has been recognized as an important cause of upper airway obstruction in children. Adult cases have been rare and it was not until 1990 that Deeb and Einhorn1 first reported seven cases. “Adult croup syndrome” was used to describe the clinical picture of community-acquired acute upper airway obstruction due to an infectious cause in the subglottic area of the larynx. The condition generally has a good prognosis and is to be distinguished from acute bacterial tracheitis, which is caused by staphylococcal infection,2, 3, 4 and tracheitis associated with immunocompromized patients or chronic debilitation.5, 6, 7, 8

We report three cases seen in a regional hospital in Hong Kong between June 1992 and March 1994. The reports are followed by a discussion of clinicopathologic features and management.

CASE REPORTS

CASE 1

A 77-year-old Chinese woman presented with prodromal symptoms of sore throat and diarrhea of 2 days' duration. There was no cough, dyspnea, or hoarseness. On physical examination, she was apyrexial. She had a weak voice and biphasic stridor without intercostal retraction. Throat examination and chest auscultation were unremarkable. A chest radiograph showed normal lung fields. In the emergency room, laryngoscopy was performed with a flexible laryngoscope. Mild subglottic mucosal edema was noted while glottic and supraglottic structures were normal. Her initial WBC count was 12×109/L. A diagnosis of acute subglottitis was made and antibiotics with humidification were prescribed.

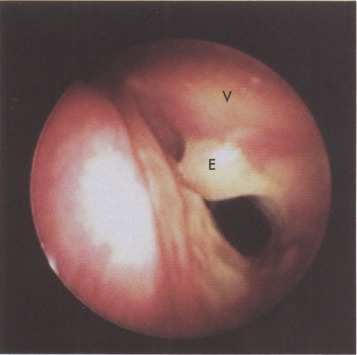

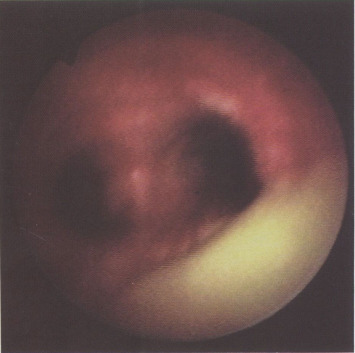

Her condition deteriorated 3 h later when she developed increased inspiratory stridor with suprasternal and supraclavicular retraction. While the patient was breathing room air, oxygen saturation was 93%. Another laryngoscopy with a flexible laryngoscope revealed progression of the subglottic edema with exudation (Fig 1 ). She was immediately intubated with a size 5.0 endotracheal tube under inhalational anesthesia. Direct laryngobronchoscopy in the operating room confirmed the endoscopic findings, and a tracheal aspirate was sent for culture which grew oral commensals only. She was observed in the ICU for another 3 days. Another bronchoscopy with a flexible bronchoscope showed that the exudation affected the entire trachea down to the level of the carina yet spared the bronchial tree (FIGURE 2, FIGURE 3 ). She was treated with intravenous antibiotics (ampicillin and sulbactam sodium, 1.5 g every 8 h; cloxaeillin sodium, 1 g every 6 h), steroids (dexamethasone, 5 mg every 6 h), and nebulized epinephrine. Her condition improved, and she was successfully extubated after a further 24 h. Laryngoscopy with a flexible laryngoscope on day 5 postintubation showed a normal subglottis and tracheal tree. The patient was discharged home after 7 days of hospitalization.

FIGURE 1.

Endoscopic view of the larynx (patient 1) showing the vocal folds (V), subglottic mass, and overlying exudates (E), day 1.

FIGURE 2.

For same patient, view of the stenosed trachea with exudation, day 4.

FIGURE 3.

For same patient, view showing inferior extent of disease at the carina, day 4.

CASE 2

A 97-year-old Chinese woman presented with fever and cough of 2 days' duration as well as progressive dyspnea. She had a medical history of fish bone ingestion 2 day's before presentation, but no foreign body was identified in the larynx. Examination revealed a temperature of 37.1°C and biphasic stridor with suprasternal retraction. Indirect laryngoscopy showed subglottic narrowing, and chest radiography was normal. The WBC count was 5.2×109/L. The presumptive diagnosis was adult croup, and this was confirmed on direct laryngobronchoscopy under inhalational anesthesia which revealed subglottic edema extending 4 to 5 cm down the trachea which was covered with thick secretions. The patient was intubated with a size 6.0 endotracheal tube. A tracheal aspirate grew oral commensals. The patient was treated in the ICU and with humidified oxygen and intravenous antibiotics (cefuroxime, 1.5 g every 8 h). Extubation was attempted after 72 h, but desaturation rapidly occurred and she was reintubated. Dexamethasone, 5 mg every 6 h, was added on day 7. On day 8. plasma sodium concentration was 111 mmol/L, and other biochemical analysis confirmed the diagnosis of a syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, presumably secondary to her airway infection. She was extubated for the second time on day 10, and endoscopy with a flexible endoscope revealed subglottic edema with sloughing. She soon developed biphasic stridor again, and tracheostomy was performed with the patient under local anesthesia. During the procedure, no abnormalities of the tracheal lumen were noted. Histologic examination of a biopsy-specimen of the tracheal wall demonstrated chronic inflammatory cell infiltration. Laryngoscopy with a flexible laryngoscope on day 20 revealed slightly edematous arytenoids, mobile vocal cords, and a normal subglottis. The tracheostomy tube was changed for a cuffless fenestrated tube. Plasma sodium level returned to 137 mmol/L on day 23, and on day 26 the tracheostomy tube was removed. Further recovery was uneventful, and the patient was discharged home after 1 month of hospitalization.

CASE 3

A 29-year-old Chinese woman presented with a 3-day history of sore throat which progressed to dysphagia, hoarseness, and shortness of breath on the day before admission to the hospital. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 38.9°C. There was no stridor, and the pharynx was mildly inflamed. Endoscopic examination with a flexible fiberoptic endoscope showed a normal epiglottis, congested false cords, and edema in the subglottic and tracheal mucosa to 2 cm below the vocal folds. The airway was judged to be adequate. An initial WBC count was 8.7×109/L with lymphocytes predominant. Intravenous antibiotics, including ampicillin, 1 g every 6 h, cefuroxime, 1.5 g, and metronidazole, 500 mg every 8 h, were immediately commenced. The initial oxygen saturation was 95 to 97% with the patient breathing room air. Five hours after admission, the oxygen saturation had fallen to 85%, but this responded to 35% oxygen therapy via a face mask. Repeated endoscopic assessment confirmed an airway of greater that 8 mm in diameter. A decision was made to continue close observation with continuous pulse oximetry and to perform endoscopy as required. The condition improved gradually over 8 h. Follow-up endoscopy on subsequent days confirmed gradual improvement of the laryngotracheitis. She was discharged on the seventh day after admission. There was no bacterial growth from the throat or laryngeal cultures. Viral titers comparing initial (less than 10) and day 14 (80) titers confirmed an episode of influenza virus type B infection.

DISCUSSION

We define adult croup as community-acquired acute laryngotracheitis in adult patients who are otherwise healthy. Together with the only other series from Deeb and Einhom,1 ten cases have been reported in the English-language literature since 1966. All these patients survived with supportive airway management. This fact distinguishes adult croup from other causes of tracheitis, with identifiable pathogens, from which patients have succumbed. In the majority of these cases, staphylococcal infections have been identified.2, 3, 4 , 9 Herpes simplex virus was isolated in one case after prolonged intubation.5 Cytomegalovirus infection6 and aspergillosis7 , 8 of the tracheobronchial tree have been diagnosed in patients with AIDS or in patients who were otherwise immunocompromized. This pattern differs from that identified in pediatric patients.10 , 11 Table 1 summarizes all pathogens identified recently as causing acute tracheitis in adults and children. The organisms responsible for croup in children are not seen in adults because of the presence of viral specific T helper and B lymphocyte memory responses. These memory responses in adults can counter the virus growth in the tracheobronchial tree and impede mucosal reactions resulting in airway obstruction. This has been confirmed in a study showing poor T helper and B lymphocyte memory responses in children with human parainfluenza 1 virus-induced croup when compared with a controlled group of adults.12

Table 1.

Organisms Responsible for Tracheitis-Croup in Adults and Children

| Organism | Adults | Children10 |

|---|---|---|

| Viral | Herpes simplex5 | Parainfluenza type 1,2 |

| Cytomegalovirus6 | Influenza type A, B | |

| Influenza B9 | Respiratory synctial virus, adenoviruses, rhinovirus, varicella-zoster, measles, echovirus, coxsackievirus group A, B, corona virus, enterovirus | |

| Bacterial | Staphylococcus aureus2, 3, 4 | Mycoplasma pneumoniae |

| Haemophilus influenzae1 | Corynebacterium diphtheriae Streptococcus pneumoniae11 | |

| Fungal | Aspergillus7,8 |

In contrast to bacterial tracheitis in which the patients present with toxic symptoms, patients with adult croup have a better prognosis. Classically, microorganisms are not isolated from the tracheal aspirates. These patients (8 of 10 cases) present with a 2- to 4-day history of prodromal illness of upper respiratory tract infection (cough, sore throat, malaise) and no fever or a low-grade fever (37 to 38.5°C). The WBC count is not markedly elevated, ranging from 5×109/L to 19×109/L with predominant lymphocytes in both reported series. Deterioration in clinical status is usually rapid; and airway intervention was required in 5 out of 10 cases (within 24 h of presentation in our 2 cases). Duration of intervention required ranged from 24 h to more than 20 days. The natural history is variable, but recovery has been satisfactory in all cases, with complete remission of airway obstruction.

Pathologic descriptions of adult croup are scarce. Indirect or flexible laryngobronchoscopy reveals mucosal edema extending down from the subglottis, leaving supraglottic structures and vocal cords unaffected. The abnormality may appear to be a subglottic or intratracheal mass resulting in luminal obstruction. In our cases, the bronchi were clearly spared (Fig 3). Our second case provides the only histologic evidence of inflammation. Exudation (Fig 2) has been noted in 3 out of 10 cases. Culture of tracheal aspirates in our cases has shown mixed commensal growth only. Serologic tests in one patient confirmed influenza B infection. Notably nonsuppurative tracheitis which progressed to toxic shock syndrome has been reported in the literature during an influenza B epidemic.9

The etiologic factors for adult croup in “immunocompetent” patients are likely to be similar to those responsible for pediatric laryngotracheobronchitis.10 The disease starts with viral replication in the nasopharynx which gradually spreads down to the tracheal mucosa, causing symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection and then stridor. The extent of mucosal involvement varies between individuals and relates to the degree of airway hyperreactivity. An additional factor we postulate may be the failure of T helper and B lymphocyte memory responses in the elderly (cases 1 and 2) although this has yet to be proven by further immunologic studies.

Management of adult croup remains empirical. The most important aspect is early recognition. We relied heavily on the use of fiberoptic examination with flexible scopes in the emergency room. Lateral neck and chest radiographs may be unreliable and inaccurate.13 Other imaging methods, such as indium 111 WBC scanning,14 are time-consuming and may delay critical airway intervention. In order to secure an adequate airway, intubation with the patient under inhalational anesthesia may be indicated. Adjuvant medical treatment for the critical airway includes oxygen, humidification, steroids, and nebulized epinephrine.1 Steroids are used to reduce edema. The use of nebulized epinephrine is not uniform in these cases but was of benefit in one of our cases (case 1). Broad-spectrum antibiotics are advisable to cover potential pathogens which may cause secondary infection. The importance of close observation of clinical signs cannot be overemphasized because the condition may deteriorate rapidly, and continuous oxygen saturation monitoring is mandatory for early detection of a compromised airway.

CONCLUSION

Adult croup is a unique disease entity in that the pathologic changes are confined to the immediate subglottis and the trachea, sparing the supraglottis and the main bronchi. Early diagnosis with the use of the flexible fiberoptic laryngoscope, close clinical monitoring, and timely airway intervention will result in a favorable outcome.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deeb ZE, Einhorn KH. Infectious adult croup. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:455–457. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson JT, Liston SL. Bacterial tracheitis in adults. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:204–205. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1987.01860020096021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruddy J. Bacterial tracheitis in a young adult. I Laryngol Otol. 1988;102:656–657. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100106036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valor RR, Polnitsky CA, Tanis DJ. Bacterial tracheitis with upper airway obstruction in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:1598–1599. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.6.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Izhak O, Ben-Arieh Y. Necrotizing squamous metaplasia in herpetic tracheitis following prolonged intubation: a lesion similar to necrotizing sialometaplasia. Histopathology. 1993;22:265–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imoto EM, Stein RM, Shellito JE. Central airway obstruction due to cytomegalovirus-induced necrotizing tracheitis in a patient with AIDS. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:884–886. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.4.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dann EJ, Weinberger M, Gillis S. Bacterial laryngotracheitis associated with toxic shock syndrome in an adult. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:437–439. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putnam JB, Jr, Dignani C, Mehra RC. Acute airway obstruction and necrotizing tracheobronchitis from invasive mycosis. Chest. 1994;106:1265–1267. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.4.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDonald KL, Osterholm MT, Hedberg CW. Toxic shock syndrome: a newly recognized complication of influenza and influenzalike illness. JAMA. 1987;257:1053–1058. doi: 10.1001/jama.257.8.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baugh R, Gilmore BB., Jr. Infectious croup: a critical review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;95:40–46. doi: 10.1177/019459988609500110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orenstein JB, Thomsen JR, Baker SB. Pneumococcal bacterial tracheitis. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9:243–245. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(91)90087-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith FS, Portner A, Leggiadro RJ. Age-related development of human memory T-helper and B-cell responses towards parainfluenza virus type-1. Virology. 1994;205:453–461. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stankiewicz JA, Bowes AK. Croup and epiglottitis: a radiological study. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:1159–1160. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198510000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai SP, Yuille DL. Necrotizing tracheobronchitis identified on an indium-111-white blood scan. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1704–1706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]