As a way of escaping from the humoral immunological response, several pathogens colonize cells and reproduce intracellularly.1 These microorganisms, however, still need to deal with intracellular antimicrobial defense mechanisms. The production of reactive nitrogen and oxygen species2, 3 as well as fusion with the lysosomal compartment are part of the innate immune cellular response. Pathogens have evolved clever ways to evade host-defense mechanisms. Typical examples are the subversion of the endocytic/phagocytic pathway to avoid acidification and fusion with lysosomes or the lysis of the phagosomal membrane in order to escape into the cytoplasm evading the harsh environment of the degradative compartments.1

A less-well-studied – and underestimated – defensive pathway is autophagy. Autophagy is a carefully orchestrated process that degrades cytoplasmic components, including organelles.4, 5 Autophagosomes are double or multimembranous vacuoles, likely emerging from specialized regions of the ER, which fuse with endosomes and lysosomes to finally degrade the sequestered materials. Activation of this pathway is an effective way of eliminating intracellular pathogens, not only those that access the cytoplasm after disrupting the phagosomal membrane6, 7, 8 but also the infectious agents that remain in the phagosomal compartment. Indeed, we have recently shown that activation of autophagy is an efficient way to eliminate Mycobacterium tuberculosis9 (see also accompanying News and Commentary in this issue). However, several thriving pathogens have developed strategies to modify and use this pathway to their own advantage.10, 11, 12 Over the last few years, accumulating evidence indicates that several pathogenic bacteria interact with the autophagic pathway.10, 12 Porphyromonas gingivalis, Brucella abortus and Legionella pneumophila gain access to and replicate in vacuoles with autophagic features. It has been postulated that autophagic vacuoles function as a shelter that protects the invading microorganisms from lytic compartments. Another advantage of using the autophagic pathway is the acquisition of nutrients given that autophagic compartments are a continuous source of small peptides and amino acids, which can be used by the bacteria via transporters.

Shortly after invasion, P. gingivalis internalized by endothelial cells is targeted to vacuoles with autophagosomal characteristics.13 When cells are treated with autophagy inhibitors, bacterial persistence decreases dramatically, suggesting that these inhibitors prevent the establishment of an intracellular niche for replication. In HeLa cells, B. abortus localizes to autophagosome-like vacuoles that contain ER markers.14 Additionally, a potential role for host autophagy in Chlamydia trachomatis pathogenesis has been proposed.15 Similar to the results obtained with P.gingivalis, exposing infected cultures to autophagy inhibitors – such as 3-methyladenine and amino acids – altered the inclusion maturation and Chlamydia growth.15

Work from our own laboratory demonstrated that Coxiella burnetii, a gram-negative bacterium, replicates in a compartment labeled by the autophagosomal protein Atg8/LC3.16 Furthermore, we have recently shown that both physiologically and pharmacologically induced autophagy favor the development of the Coxiella replicative vacuole.19 Our results also indicate that overexpression of proteins involved in the autophagic pathway accelerate the biogenesis of the Coxiella-parasitophorous vacuole, favoring bacterial replication at early times after infection.19 Likewise, immediately after L. pneumophila internalization, the autophagic markers Atg7 and Atg8 are recruited to the Legionella phagosomal compartment.17 These results clearly indicate that similarities exist between these two pathogenic bacteria.

L. pneumophila and C. burnetii are indeed very close relatives. These two bacteria are known to utilize a type-IVB secretion system for pathogenesis.18 Type IV secretion systems are molecular devices present in numerous pathogenic microorganims that deliver molecules to subvert or bypass host defenses. This machinery consists of bacterial membrane proteins assembled in an apparatus that injects bacterial proteins into the host. An interesting new finding is that autophagy is activated by molecules secreted via the Legionella Type IV system, as indicated by the processing of Atg8 and the formation of autophagic vacuoles.17 Similarly, we have observed that numerous LC3/Atg8 decorated vesicles are formed in Coxiella-infected CHO cells19 and we have proposed that Type IV secretion of bacterial molecules activates autophagy in the host cell. A protein secreted by the Type III system in Salmonella also induced autophagy in infected macrophages.20 These secreted molecules may promote the formation of sequestering vacuoles, or may delay their maturation in order to allow the bacteria to become resistant to lysosomal degradation. Indeed, it has been shown that vacuoles that harbor Legionella, as well as the autophagic vacuoles stimulated by the Legionella-released factors, mature more slowly than normal cellular autophagosomes.17

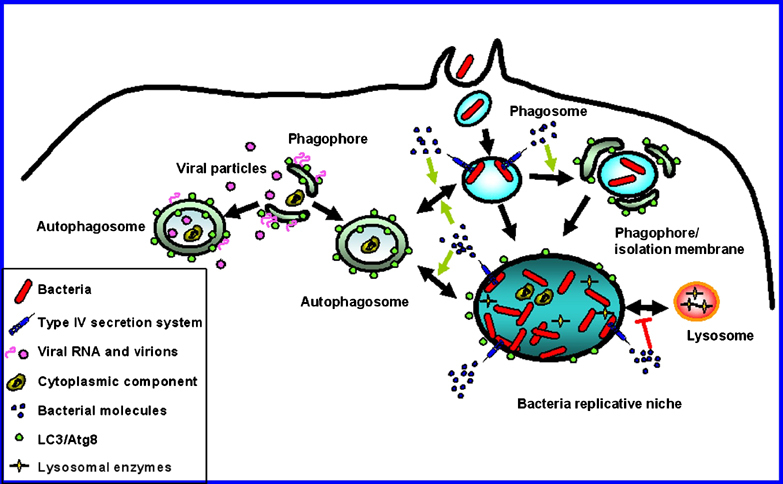

It has been proposed that cells are also protected against viral infection by autophagy.10, 12 However, in the case of mouse hepatitis coronavirus, replication complexes colocalize with the autophagy proteins LC3 and Atg12.21 Furthermore, in cells deficient for the autophagy gene Atg5, a marked reduction in extracellular virus yield was reported. A very recent publication evinced that reduction in Atg12 and LC3 by siRNA resulted not only in a reduction of extracellular polio virus but also in decreased intracellular pools.22 Viral RNA replication complexes localize to the surface of double membrane structures with the hallmarks of immature autophagosomes. Thus, present evidence suggests that RNA viruses subvert the cellular autophagosomal machinery to facilitate virus replication. It has also been proposed that nonenveloped viruses such as poliovirus use the autophagic pathway as a nonlytic mechanism for viral release. As viral infection progresses, some double-membrane vesicles would contain virions that are prevalent in the cytoplasm late in infection. Viral particles would subsequently be released into the extracellular media after fusion of these membrane bound structures with the plasma membrane.22 In Figure 1, a model is shown depicting how both bacterial pathogens and virus subvert the autophagy pathway to promote bacterial and viral RNA replication.

Figure 1.

Subvertion of the autophagic pathway by both bacteria and viruses. Shortly after internalization, bacteria secrete molecules via a Type IV secretion system. The secreted molecules likely activate fusion of bacteria-containing phagosomes with LC3-labeled autophagosomes. Alternatively, the sequestration of phagosomes by phagophores or isolation membranes may also be promoted. Interaction with the autophagic pathway favors the development of the bacterial replicative niche delaying fusion with lysosomes until a resistant bacterial form is generated. Viral RNA replication complexes localize to the surface of double-membrane structures with the hallmarks of immature autophagosomes. Late in infection, viral particles present in the cytoplasm are engulfed in autophagosomes upon phagophore closure. Double-headed arrows indicate interaction or fusion between the compartments

Increasing evidence supports a link between autophagy and apoptosis.23 An interesting point is that Naip proteins (Neuronal Apoptosis Inhibitor Proteins) are involved in pathogen infection. Mice A/J – susceptible to L. pneumophila, Trypanosoma cruzi and Listeria monocytogenes infection – present a mutation in Naip5, a member of the Naip family that function as endogenous caspase inhibitors. In a recent publication, it was shown that autophagosomes mature more slowly in A/J mouse macrophages,17 suggesting that Naip5, a negative regulator of apoptosis, may control whether cells respond to infection by executing autophagy or apoptosis.

It is evident that modulation of host cell apoptosis or autophagy by intracellular bacterial pathogens plays an important role in pathogenesis.24 Induction of apoptosis could contribute to the escape and dissemination of certain intracellular bacteria. Pathogens might also regulate the expression of antiapoptotic genes to avoid triggering apoptosis until the microorganism has sufficiently replicated in the host cell. On the other hand, they may regulate the autophagic response not only as a prosurvival mechanism but also to generate a more permissive niche for intracellular replication. It is clear that switching between one or other mechanism would vary between different pathogens. Comprehensive studies of each particular case would allow us not only to evaluate their contribution to pathogenesis but also to advance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of autophagic and apoptotic pathways.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Karla Kirkegaard (Stanford University, California) for useful comments. MIC's own work is funded by grants from Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT2002 # 01-11004), NIH Fogarty International Center grant RO3 TW06982, Secyt (Universidad Nacional de Cuyo) and UJAM (Universidad Juan A. Maza).

References

- 1.Alonso A and Garcia-del Portillo F (2004) Int. Microbiol.7: 181–191 [PubMed]

- 2.Nathan C and Shiloh MU (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.97: 8841–8848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Fang FC (2004) Nat. Rev. Microbiol.2: 820–832 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Yoshimori T (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.313: 453–458 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Levine B and Klionsky DJ (2004) Dev. Cell6: 463–477 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Rich Kathryn A., Burkett Chelsea, Webster Paul. Cytoplasmic bacteria can be targets for autophagy. Cellular Microbiology. 2003;5(7):455–468. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakagawa I. Autophagy Defends Cells Against Invading Group A Streptococcus. Science. 2004;306(5698):1037–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.1103966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogawa M. Escape of Intracellular Shigella from Autophagy. Science. 2005;307(5710):727–731. doi: 10.1126/science.1106036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutierrez Maximiliano G., Master Sharon S., Singh Sudha B., Taylor Gregory A., Colombo Maria I., Deretic Vojo. Autophagy Is a Defense Mechanism Inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis Survival in Infected Macrophages. Cell. 2004;119(6):753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorn Brian R., Dunn William A., Progulske-Fox Ann. Bacterial interactions with the autophagic pathway. Cellular Microbiology. 2002;4(1):1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson Michele S., Fernandez-Moreia Esteban. A Microbial Strategy to Multiply in Macrophages: The Pregnant Pause. Traffic. 2002;3(3):170–177. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.030302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkegaard K et al. (2004) Nat. Rev. Microbiol.2: 301–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Dorn BR et al. (2001) Infect. Immun.69: 5698–5708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Pizarro-Cerda J et al. (1998) Infect. Immun.66: 5711–5724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Al Younes HM et al. (2004) Infect. Immun.72: 4751–4762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Berón W et al. (2002) Infect. Immun.70: 5816–5821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Amer Amal O., Swanson Michele S. Autophagy is an immediate macrophage response to Legionella pneumophila. Cellular Microbiology. 2005;7(6):765–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segal G et al. (2005) FEMS Microbiol. Rev.29: 65–81 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Gutierrez MG et al. (2005) Cell Microbiol.7: 981–994 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hernandez LD et al. (2003) J. Cell Biol.163: 1123–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Prentice E et al. (2004) J. Biol. Chem.279: 10136–10141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Jackson WT et al. (2005) PLoS. Biol.3: e156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Lockshin RA and Zakeri Z (2004) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol.36: 2405–2419 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Gao LY and Kwaik YA (2000) Trends Microbiol.8: 306–313 [DOI] [PubMed]