Abstract

Motivation: High-throughput ‘ChIP-chip’ and ‘ChIP-seq’ methodologies generate sufficiently large data sets that analysis poses significant informatics challenges, particularly for research groups with modest computational support. To address this challenge, we devised a software platform for storing, analyzing and visualizing high resolution genome-wide binding data. GeneTrack automates several steps of a typical data processing pipeline, including smoothing and peak detection, and facilitates dissemination of the results via the web. Our software is freely available via the Google Project Hosting environment at http://genetrack.googlecode.com

1. INTRODUCTION

Current genomic technologies generate millions of data points from a single biological experiment. As these technologies are now mainstream, the resulting data are straining bioinformatics pipelines. Consequently, our understanding of genome regulation is becoming more analysis-limited rather than data-limited. First generation genome technologies (such as microarrays) increased data gathering capacity significantly. Bioinformatics tools to manage, display and analyze this data were developed Quackenbush (2006), including the UC-Santa Cruz genome browser Kent et al. (2002), the Generic Genome Browser Stein et al. (2002), GenoViz platform and the Integrated Genome Browser, NCBI for raw archiving and GALAXY Blankenberg et al. (2007) for data analysis tools. Second generation technologies (such as tiling microarrays and whole-genome sequencing) have the potential to increase data acquisition dramatically. Here, we introduce a new software platform named GeneTrack that we have developed to automate and facilitate large-scale downstream data processing of chromatin immunoprecipitation data obtained via high-throughput sequencing and tiling arrays Albert et al. (2007). Our software is unique in that it integrates multiple steps of a typical data analysis process: smoothing, fitting, peak detection and visualization into a single workflow and that it performs to specifications on limited hardware. GeneTrack employs rapid processing and has low computational demands which make it suitable for exploratory data analyses where different fitting and peak detection parameters are varied and the results compared on the same display. GeneTrack was developed in the Python programming language, using the hierarchical data format (HDF) as its data storage backend and the NumPy library for numerical computation. For a better integration with existing tools final results are written into a relational database with support for all major databases: including MySQL, PostgreSQL, Oracle and MS-SQL. Notably, the system does not require the presence of a separate database or webserver for small-scale deployments. Our software is able to use the SQLite relational database engine that is distributed with Python 2.5, moreover, it can present data through the web via its own embedded web server, thus is ideal for smaller, individual research groups. Setup, maintenance and administration are controlled via a single program to provide the following functionality:

store and retrieve data efficiently,

quickly smooth data over an entire chromosome,

combine strand specific data into a composite value,

detect peaks rapidly over a chromosome-wide scale,

display and publish results via an embedded webserver.

2. METHODS

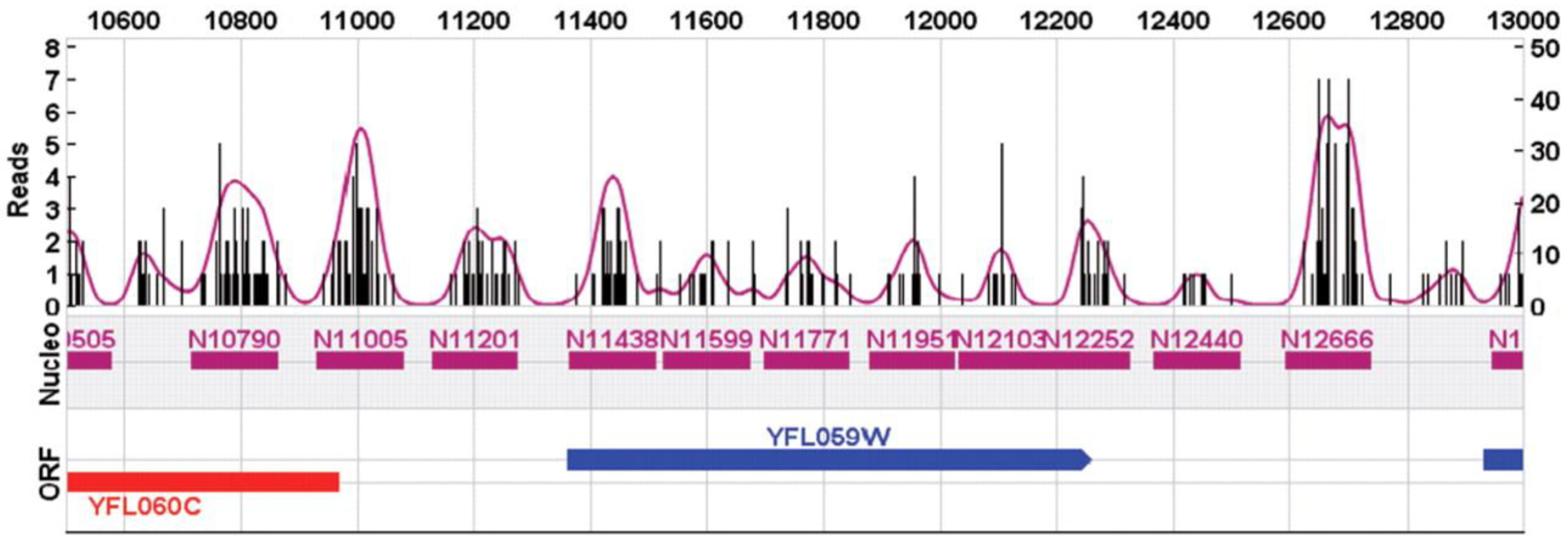

The HDF provides a versatile data model that represents complex data objects and a wide variety of metadata in a portable file format with no limit on the number or size of data objects in the collection. We adopted HDF as the data storage backend for GeneTrack and we chose NumPy to provide high-speed numerical computation. GeneTrack works iteratively, processing data in individual, overlapping chunks, thus keeping the memory consumption low and independent of characteristics of the data. Data smoothing and averaging is accomplished by a Gaussian smoothing procedure as follows: a measurement at a genomic coordinate is approximated by values taken from a normal distribution of height equal to the measurement, centered over the measurement’s coordinate, and, with a standard deviation that acts as an external, tunable parameter (fitting tolerance). Consequently, each measurement is expanded into many values over a contiguous set of coordinates. Next, all individually fitted values are summed at each genomic coordinate resulting in a smooth and continuous ‘probabilistic land-scape’ where the peaks of the curve indicate the most likely positions of the measured genomic feature. Finally, the peak detection algorithm in GeneTrack operates by selecting the maximal non-overlapping subset from all local maxima in the data. That is, the algorithm selects the highest peak along the chromosome, then establishes an exclusion zone (typically a few hundred bp), within which no other subsequent peaks are allowed to fall. In the rare occasion that two close peaks (inside the exclusion zone) have exactly equal height only one of them will be selected as valid. The process is repeated iteratively over the remaining space until no other peaks may be placed. This algorithm is well suited for problems where genomic features have a certain a priori known width (e.g. 147 bp nucleosomal DNA), Setting the exclusion zone to 0 turns off this feature, and allows the algorithm to determine the optimal placement of heterogeneously sized DNA fragments that are typically generated in ChIP-seq experiments. Figure 1 illustrates the output derived from 1.3 million ChIP-seq ‘reads’ of the Saccharomyces genome.

Fig. 1.

GeneTrack Composite Plot. Black vertical bars represent experimental sequencing reads that map to a genomic coordinate. The purple trace represents the smoothed fit over the read values. The purple horizontal tracks represent the 147 bp-wide nucleosome predictions as given by the peak detection algorithm. The blue and red tracks are yeast ORFs on the forward (blue) and reverse (red) strands.

3. RESULTS

GeneTrack is controlled via a single program and a configuration file that specifies the processes that it should perform (various data analysis steps or web serving and/or plotting). The input for the analysis must be a tab-delimited text file that lists chromosome, genomic coordinates and values on forward or reverse strands. For experimental methodologies (ChIP-chip) that do not separate strands, the values on the reverse strand may be set to zero. Detailed documentation is available in a searchable Wiki format, containing installation instructions and other operational details (see main website). The code distribution also includes a data set and configuration files for the work published elsewhere Albert et al. (2007), packaged such that users may repeat a full data analysis and view the results via the embedded web server within minutes.

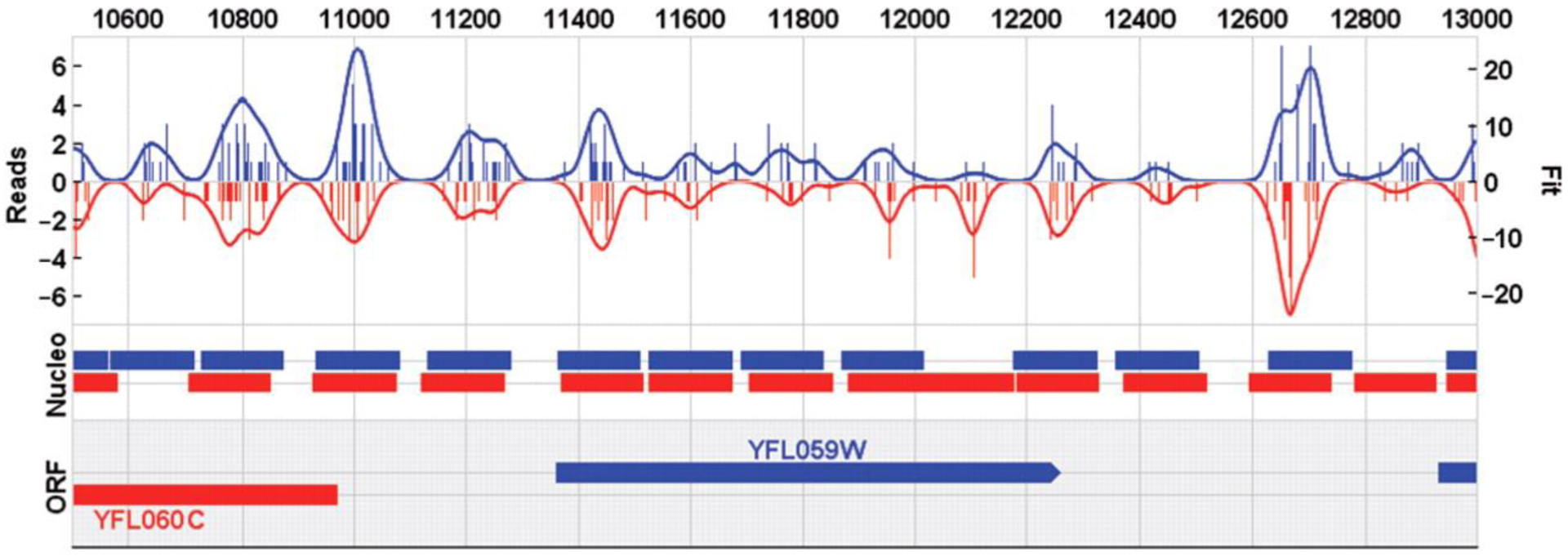

Internally, all information is represented on forward, reverse and ‘composite’ strands, where the composite strand is a combination (in the simplest case a sum) of the data on each individual strand. Since data on the forward and reverse strand represent two independent determinations of binding, this approach allows for individual error evaluations to be made whenever the data on the two strands are in disagreement. GeneTrack will automatically operate on each strand separately (Fig. 2) and will derive the values for the composite strand as well.

Fig. 2.

GeneTrack Two Strand Plot. Within the software full strand information is maintained. The same plot from Figure 1 is now visualized on the separate strands forward (blue) and reverse (red). An ideal signal would be perfectly mirrored; this type of display allows one to identify systematic shifts in the data. Note how the fitting and peak prediction algorithms also operate on separate strands.

The software was designed with extensibility in mind. There is a clear separation of the database schemas, parsing, fitting and prediction modules, to the extent that the schema or prediction algorithm that is to be invoked in a certain analysis run can be changed via the configuration file. Similarly, the output tracks and graphs are fully customizable and may be entirely replaced although this requires Python expertise. The currently distributed schemas are for sequencing data, but we are preparing a set of modules to streamline tiling array data processing. We are committed to providing a smooth data exchange with other existing data analysis and visualization platforms provided by UCSC and Ensemble. To that end we have implemented export functionality that produces results in BED, GFF or wiggle format. The software has been tested on Windows and Linux platforms and is believed to work on all major operating systems that can run Python and its extension libraries for HDF and Numerical Python. We maintain several GeneTrack instances to disseminate our results (see http://atlas.bx.psu.edu). Funding for the project has been provided by NIH R01-HG004160.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Albert I et al. (2007) Translational and rotational settings of H2A.Z nucleosomes across the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature, 446, 572–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberg D et al. (2007) A framework for collaborative analysis of ENCODE data: making large-scale analyses biologist-friendly. Genome Res., 17, 960–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ et al. (2002) The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res., 12, 996–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quackenbush J (2006) Computational approaches to analysis of DNA microarray data. Methods Inf. Med, 45 (Suppl. 1), 91–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein LD et al. (2002) The generic genome browser: a building block for a model organism system database. Genome Res., 12, 1599–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]