Abstract

Mitochondrial dynamics shape the mitochondrial network and contribute to mitochondrial function and quality control. Mitochondrial fusion and division are integrated into diverse cellular functions and respond to changes in cell physiology. Imbalanced mitochondrial dynamics are associated with a range of diseases that are broadly characterized by impaired mitochondrial function and increased cell death. In various disease models, modulating mitochondrial fusion and division with either small molecules or genetic approaches has improved function. Although additional mechanistic understanding of mitochondrial fusion and division will be critical to inform further therapeutic approaches, mitochondrial dynamics represent a powerful therapeutic target in a wide range of human diseases.

Introduction

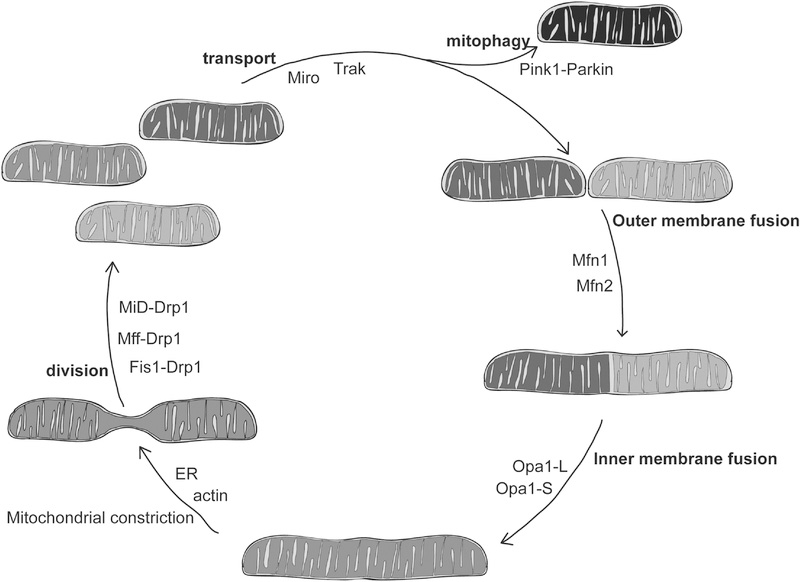

Mitochondrial structure and function vary remarkably across different cell and tissue types (Kuznetsov et al., 2009). The structure of the mitochondrial network changes through fusion, division and transport based on cellular needs (Figure 1). The balance between fusion and division is required to support the metabolic functions of mitochondria that power diverse cellular processes (Wai and Langer, 2016). For example, mitochondrial dynamics change during the cellular response to stress (Eisner et al., 2018). In some conditions that adversely impact cellular health, such as nutrient limitation (Gomes et al., 2011) or modest inhibition of cytosolic protein synthesis (Tondera et al., 2009), the mitochondrial network becomes highly interconnected, which facilitates ATP production and promotes cell survival. Mitochondria are also integrated into cell cycle progression and cell death pathways, placing them at the heart of cellular life and death decisions (Horbay and Bilyy, 2016; Kalkavan and Green, 2018; Otera and Mihara, 2012; Salazar-Roa and Malumbres, 2017). In proliferating cells, increased mitochondrial division prior to mitosis fragments the network to facilitate mitochondrial inheritance during cell division, while decreased division upon entry to S-phase results in a more highly connected network (Mitra et al., 2009; Taguchi et al., 2007). High levels of DNA damage, on the other hand, activate apoptotic pathways and induce mitochondrial fragmentation (Frank et al., 2001; Karpinich et al., 2002). Together, the complex regulation of mitochondrial dynamics is essential to facilitate diverse cellular functions.

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial fusion, division and transport mediate changes in mitochondrial structure and function.

Mitochondrial dynamics are required during development, particularly in the heart (Dorn et al., 2015; Gong et al., 2015) and brain (Flippo and Strack, 2017), and also have a role in stem cell self-renewal and differentiation (Chen and Chan, 2017; Seo et al., 2018). Consistent with this, diseases caused by loss or dysfunction of the mitochondrial fusion or division machines are broadly characterized by developmental delays and neurodegeneration (Bertholet et al., 2016; Burté et al., 2015). Many other diseases with diverse genetic and environmental causes are associated with altered mitochondrial shape, including common neurodegenerative diseases (J. Gao et al., 2017), heart failure (Brown et al., 2017), diabetes (Rovira-Llopis et al., 2017), and cancer (Trotta and Chipuk, 2017). In some cases, disease-associated changes in mitochondrial structure can be attributed to altered expression of the mitochondrial fusion and division proteins. In other cases, aberrant signaling pathways are predicted to alter mitochondrial dynamics. In either case, aberrant mitochondrial structure is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, which contributes to disease pathology.

Therapeutics that address mitochondrial dysfunction have a potentially broad clinical impact. In particular, treatments that re-establish the balance of fusion and division might improve cellular function and survival, leading to improved patient outcomes. Balanced mitochondrial dynamics are required for the inheritance and integrity of the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA), which encodes essential components of the electron transport chain (Chen et al., 2010; Mishra and Chan, 2014). Aberrant mitochondrial structure and accumulation of mutations in mtDNA are both reported to increase with age and have been hypothesized to contribute to declining mitochondrial and cellular function (Sun et al., 2016). Imbalanced mitochondrial fusion and division also impact the turnover of damaged proteins and organelles by mitophagy (Burman et al., 2017; Chen and Dorn, 2013; Narendra et al., 2008; Song et al., 2015). Specifically, a connected mitochondrial network can protect against mitochondrial turnover, in particular during cellular autophagy in response to starvation (Gomes et al., 2011), while mitochondrial division can promote turnover of dysfunctional organelles (Pickles et al., 2018). In some cases, preventing mitochondrial fragmentation could impact cell death decisions by reducing cellular sensitivity to apoptotic signals (Cereghetti et al., 2010). However, there are exceptions to these general trends. For example, in many cancerous cells, mitochondrial fragmentation is associated with metabolic changes that support rapid growth and survival (Anderson et al., 2018; Inoue-Yamauchi and Oda, 2012) and in this case, it may slow growth and sensitize these cells to death if the network were more connected.

Given the critical role of mitochondrial structure and function in cellular physiology, mitochondrial dynamics have been targeted in several disease model systems utilizing both genetic and pharmacological approaches to restore balanced mitochondrial fusion and division (Archer, 2013; Flippo and Strack, 2017; Suárez-Rivero et al., 2016; Wai and Langer, 2016). In fact, rebalancing mitochondrial dynamics in a genetic disease animal model has been shown to improve tissue function and extend lifespan (Chen et al., 2015). Genetic therapies have altered the expression of the genes encoding mitochondrial fusion and division proteins to rebalance mitochondrial dynamics. Chemical therapeutics have targeted known elements of the mitochondrial fusion and division mechanisms, including their enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions, and post-translational modifications (PTMs). In this review, we first present an overview of the mechanisms of mitochondrial division and fusion to provide a framework for describing existing and potential therapeutic approaches. We then discuss approaches to restore mitochondrial dynamics in model systems that target abnormal expression of the mitochondrial fusion and division machines and finally the development of small molecules that affect the activity of these proteins. We conclude with a brief discussion of other potential druggable targets that could improve mitochondrial structure and function in disease states.

The mitochondrial division machine, Drp1

Mitochondrial division requires the coordinated action of many factors (Kraus and Ryan, 2017). Division occurs primarily at mitochondria-ER contact sites (Friedman et al., 2011) where actin-mediated constriction of the mitochondria activates downstream steps in the division pathway (Moore and Holzbaur, 2018). These mitochondria-ER contact sites also couple mtDNA synthesis to mitochondrial division, facilitating the distribution of mtDNA (Lewis et al., 2016). Dynamin-related protein 1, Drp1, is a large GTPase required for mitochondrial division from yeast to mammals (Bleazard et al., 1999; Labrousse et al., 1999; Smirnova et al., 2001). Drp1 is recruited to the mitochondrial outer membrane by resident protein receptors including Mff, Fis1, MiD49, and MiD51 (Losón et al., 2013). Higher order assembly of Drp1 at mitochondrial constriction sites is stimulated by cardiolipin (Francy et al., 2017) to form large helical structures (Clinton et al., 2016; Fröhlich et al., 2013). Nucleotide binding and hydrolysis by Drp1 promote its assembly, conformational changes and disassembly to drive mitochondrial division (Kalia et al., 2018). In some cases, Dynamin-2 may also be required to further constrict the mitochondria following Drp1 (Kamerkar et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2016).

The Drp1 receptor proteins, Mff, Fis1, MiD49 and MiD51, are functionally distinct. MiD49 and MiD51 can act independently from Fis1 and Mff in Drp1 recruitment (Losón et al., 2013; Palmer et al., 2013). Loss of both MiD49 and Mff was more severe than loss of either one alone, suggesting that these receptors impact division in distinct ways (Osellame et al., 2016). MiD49 and MiD51, but not Mff, have also been implicated in cristae remodeling during apoptosis (Otera et al., 2016). Notably, the role of Fis1 in Drp1-mediated mitochondrial division has recently been challenged as new evidence suggests that Fis1 does not interact with Drp1, but with components of the fusion machine to inhibit their activity (Osellame et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2019).

Post-translational modification of Drp1 and its mitochondrial receptors, Mff and MiD49, promotes rapid changes in mitochondrial division activity based on cellular needs. Drp1 assembly and GTPase activity can be stimulated by nitrosylation of its C-terminal GTPase effector domain (Cho et al., 2009). Phosphorylation and SUMOylation of Drp1 regulate the activity and mitochondrial recruitment of cytosolic Drp1 (Otera et al., 2013). Drp1 phosphorylation by Cdk1 at S616 promotes mitochondrial fragmentation during mitosis (Taguchi et al., 2007). Other kinases such as MAPK, Cdk5 and CAMKII can also phosphorylate Drp1-S616 to promote mitochondrial division, which has been associated with tumor growth (Kashatus et al., 2015; Serasinghe et al., 2015), as well as cell death in neurons (Guo et al., 2018) and hearts (Shangcheng Xu et al., 2016). PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Drp1-S637 inhibits its activity (Chang and Blackstone, 2007; Cribbs and Strack, 2007), while calcineurin-mediated dephosphorylation of S637 promotes division by recruiting Drp1 to the mitochondria (Cereghetti et al., 2008; Cribbs and Strack, 2007). Interestingly, phosphorylation of S637 by CaMK1α (Han et al., 2008) and ROCK1 (Wang et al., 2012) increased division activity, suggesting that in addition to the site of phosphorylation, the cellular context influences how phosphorylation affects Drp1 activity.

Drp1 can also be modified by different SUMO paralogs (SUMO-1 or SUMO-2/3). During apoptosis, SUMOylation of Drp1 with SUMO-1 promotes mitochondrial division by stabilizing Drp1 on the mitochondria (Harder et al., 2004; Prudent et al., 2015; Wasiak et al., 2007). In contrast, removal of SUMO-2/3 from Drp1 by SENP3 also increased division by promoting the interaction of Drp1 with Mff (Guo et al., 2017). The interaction of Mff and Drp1 is also regulated by phosphorylation. Mitochondrial division was stimulated by AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of Mff, which promoted Drp1 recruitment to mitochondria (Toyama et al., 2016). Finally, mitochondrial division activity can be modulated by ubiquitination of Drp1 (Horn et al., 2011; H. Wang et al., 2011) and its receptor MiD49 (Cherok et al., 2017; S. Xu et al., 2016), which promotes protein turnover and therefore reduced division activity. Together, the distinct post-translational modifications of Drp1 and its receptors highlight how mitochondrial division is integrated with numerous cellular pathways.

The mitochondrial fusion machines, Mitofusin and Opa1

Outer membrane fusion

Mitochondrial fusion is also mediated by dynamin-related GTPase proteins. Mitofusin 1 (Mfn1) and Mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) mediate mitochondrial outer membrane fusion in vertebrates (Chen et al., 2003; Santel and Fuller, 2001). Mfn2 has additional cellular functions including mitochondria-ER contact site formation and stability (de Brito and Scorrano, 2008; Filadi et al., 2015; Naon et al., 2016), mitochondria-lipid droplet interactions (Boutant et al., 2017), cellular proliferation (Chen et al., 2014; 2004), metabolic signaling (Bach et al., 2003; Zorzano et al., 2015), and mitophagy (McLelland et al., 2018). The topology of the Mitofusin proteins is under debate. Recent biochemical analyses are consistent with a single transmembrane domain resulting in the C-terminus residing in the intermembrane space (Mattie et al., 2018), while the structural data for the Mitofusin suggests that the C-terminus is a component of the helical bundle proximal to the GTPase domain in the cytoplasm (Cao et al., 2017; Y. Qi et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2018). Mitochondrial fusion is most efficient when both Mitofusin paralogs are present, indicating that they are functionally distinct (Chen et al., 2003; Detmer and Chan, 2007; Hoppins et al., 2011a). Mitofusin proteins are predicted to initiate fusion in a membrane tethering step through interactions between proteins on opposing membranes of a fusion pair (Hoppins et al., 2011b; Ishihara et al., 2004). While atomic resolution structures of a partial Mfn1 construct suggest that an intermolecular interface of the globular GTPase domains mediates tethering (Cao et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2018), an alternative model proposes that the C-terminal domain is required for this step (Franco et al., 2016; Koshiba et al., 2004). Biochemical analysis indicates that Mitofusins assemble into higher order oligomers (Ishihara et al., 2004; Karbowski et al., 2006; Pyakurel et al., 2015; Shutt et al., 2012). Although the role of Mitofusin assembly in membrane fusion is not well defined, visualization of tethered mitochondria by electron cryo-tomography suggests that Fzo1, the yeast Mitofusin homolog, forms a docking ring that precedes mitochondrial outer membrane fusion (Brandt et al., 2016).

Post-translational modification of the Mitofusins regulates both protein turnover and activity. Acetylation of Mfn1 at K222 and K491 was reported to decrease mitochondrial connectivity and increase oxidative damage (Lee et al., 2014) and ubiquitination of Mfn1 (Park et al., 2014). Deacetylation of Mfn1 in response to glucose withdrawal was associated with highly connected mitochondrial networks and improved mitochondrial function (Lee et al., 2014). Mfn1 phosphorylation at multiple sites can also inhibit fusion activity through distinct mechanisms (Ferreira et al., 2019; Pyakurel et al., 2015). In failing hearts, phosphorylation of Mfn1 at S86 by beta II protein kinase C (ßIIPKC) reduced the GTPase activity of Mfn1 and led to mitochondrial fragmentation (Ferreira et al., 2019). ERK phosphorylation of Mfn1 at T562 attenuated Mfn1 assembly and increased its interaction with the pro-apoptotic protein, Bak, which together inhibited fusion and promoted cell death (Pyakurel et al., 2015). Finally, mitochondrial fusion activity can be modulated by both phosphorylation of Mfn2 (Chen and Dorn, 2013) and ubiquitination (Covill-Cooke et al., 2018). Mfn2 ubiquitination has also been implicated in mitochondrial-ER contact site remodeling and increased mitophagy, although the mechanism by which ubiquitin alters mitochondrial-ER contact sites is disputed (Basso et al., 2018; McLelland et al., 2018; Sugiura et al., 2013). Therefore, PTMs of Mitofusins also serve to regulate their activity and integrate mitochondrial dynamics into a variety of cellular pathways.

Inner membrane fusion

Mitochondrial outer membrane fusion is spatially and temporally coupled to inner membrane fusion (Cipolat et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2009). The dynamin-related GTPase Optic atrophy 1 (Opa1) is required for inner membrane fusion (Olichon et al., 2003; Song et al., 2007). Multiple forms of Opa1 are found in different tissues due to alternative splicing and proteolytic processing by the inner membrane peptidases Oma1 and Yme1, which generate two topologically distinct isoforms of Opa1. The unprocessed long form (Opa1-L), is anchored to the inner membrane and the cleaved form lacks the transmembrane domain, generating short, soluble form in the intermembrane space (Opa1-S). While some studies suggest that both Opa1-L and Opa1-S are required for inner membrane fusion (Song et al., 2007), recent data indicate that Opa1-L and cardiolipin are sufficient to mediate membrane fusion (Anand et al., 2014; Ban et al., 2017). Opa1 is primarily regulated through its proteolytic cleavage by inner membrane proteases whose activities are altered by ATP and membrane potential. The increased proteolytic processing of Opa1 inhibited fusion and was proposed to function as a mechanism to sequester damaged mitochondria from the network for turnover (Ehses et al., 2009; Griparic et al., 2007; Head et al., 2009; Mishra et al., 2014; Song et al., 2007). In addition to its role in membrane fusion, Opa1 is also important for maintaining the organization and structure of the mitochondrial inner membrane (Frezza et al., 2006; Olichon et al., 2003). Therefore, modulating Opa1 activity could impact both the connectivity of the mitochondrial network and inner membrane structure, which both influence mitochondrial functions in health, such as oxidative phosphorylation, and in disease, such as membrane permeabilization during apoptotic cell death.

Genetic models of disease and therapeutic approaches

Loss of fusion or division activity as the primary cause of human disease

Diseases caused by loss of fusion and division activity share common clinical features, including developmental defects and neurological dysfunction. Consistent with a vital role for mitochondrial dynamics during development, homozygous deletion of MFN1, MFN2, OPA1 or DNM1L in mice does not support viable embryonic development (Chen et al., 2003; Davies et al., 2007; Ishihara et al., 2009). Placental defects likely contributed to embryonic lethality in Mfn2 and Drp1 knockout mice (Chen et al., 2003; Wakabayashi et al., 2009), while cardiac and neuronal developmental defects were also observed Drp1 knockout embryos (Wakabayashi et al., 2009). The impact of imbalanced mitochondrial dynamics on neuronal development is emphasized by the perinatal lethality after pan-neuronal (Ishihara et al., 2009) or cerebellar knockout (Wakabayashi et al., 2009) of DNM1L in the mouse brain. While mice died primarily from a suckling defect, giant mitochondria were aggregated in neuronal cell bodies, which was associated with impaired synapse formation (Ishihara et al., 2009; Wakabayashi et al., 2009).

Human mutations in DNM1L impair Drp1 enzymatic activity, assembly and mitochondrial recruitment and cause a range of diseases characterized broadly by developmental delays and neurological dysfunction (Chang et al., 2010; Chao et al., 2016; Fahrner et al., 2016; Sheffer et al., 2016; Vanstone et al., 2016; Waterham et al., 2007; Whitley et al., 2018; Zaha et al., 2016). Cells isolated from patients with de novo, heterozygous DNM1L mutations had elongated and extensively connected mitochondria (Sheffer et al., 2016; Vanstone et al., 2016; Waterham et al., 2007; Whitley et al., 2018; Zaha et al., 2016) that mirrored the morphology observed in MEFs lacking Drp1 (Wakabayashi et al., 2009). Expression of mutant Drp1 variants in wild type cells interfered with normal division activity, consistent with the dominant inheritance pattern (Chang et al., 2010; Fahrner et al., 2016; Waterham et al., 2007; Whitley et al., 2018). Elongated, or highly fused mitochondria are also observed in diseases caused by mutations in the genes encoding the Drp1 receptors Mff (MFF) (Koch et al., 2016; Nasca et al., 2018; Shamseldin et al., 2012) and MiD49 (MIEF2) (Bartsakoulia et al., 2018). Mutations in MFF are associated with developmental delay, Leigh Syndrome-like neuropathy (Koch et al., 2016; Nasca et al., 2018; Shamseldin et al., 2012), and cardiomyopathy (H. Chen et al., 2015) while a recently reported mutation in MIEF2 was associated with skeletal muscle dysfunction instead of neuronal dysfunction (Bartsakoulia et al., 2018).

Mutations in MFN2 cause the peripheral, sensorimotor neuropathy Charcot Marie Tooth Syndrome Type 2A (CMT2A) (Barbullushi et al., 2019; Stuppia et al., 2015; Züchner et al., 2004). In addition to altered mitochondrial fusion, some of the neuronal defects in CMT2A models have been attributed to impaired mitochondrial transport and distribution in cultured rodent (Baloh et al., 2007; Misko et al., 2010) and fly neurons (Fissi et al., 2018). Molecular characterization in model systems suggest that Mfn2 disease-associated variants may fall into unique functional classes that differently alter mitochondrial structure (Detmer and Chan, 2007; Fissi et al., 2018). In cell culture models of CMT2A, Mfn1 expression rescued morphological (Detmer and Chan, 2007) and transport (Misko et al., 2010) defects in a subset of Mfn2 CMT2A mutant variants. Recently, expression of Mfn1 was shown to rescue the neurodegenerative phenotype in mice expressing a CMT2A mutant variant of Mfn2 (Zhou et al., 2019). Therefore, gene therapies that increase Mfn1 in affected tissues may alleviate patient symptoms. Charcot Marie Tooth (CMT) disease is one of the most common inherited neurological disorders, with several distinct classes and many different genes that are mutated in patients. Gene therapies targeting other CMT neuropathies have alleviated cellular dysfunction caused by either dominant-negative alleles (Kagiava et al., 2018) or haploinsufficiency (Sahenk et al., 2014), suggesting that a similar approach may be a viable disease treatment for CMT2A.

Neuronal degeneration in dominant optic atrophy (DOA) is caused by mutation or heterozygous loss of OPA1 (Alavi et al., 2009; Chun and Rizzo, 2016; Kushnareva et al., 2016; Sarzi et al., 2012). Knock-in of a common, non-functional DOA-causing OPA1 variant, OPA1delTTAG caused progressive degeneration of the retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) in mice. RGC degeneration was rescued by exogenous expression of wild type OPA1 in the surviving neurons of these Opa1+/delTTAG mice (Sarzi et al., 2018). Optic atrophy is also associated with a mutation in YME1L, which encodes one of the inner membrane proteases that cleaves Opa1-L. In this patient, YME1L missense mutations resulted in instability of Yme1 protein, causing improper Opa1 processing and mitochondrial fragmentation (Hartmann et al., 2016).

As exome sequencing has become more feasible and widely used, amino acid substitutions in mitochondrial fusion proteins have been associated with additional diseases. Missense mutations in OPA1 have recently been linked to a type of parkinsonism (Carelli et al., 2015) and an MFN2 polymorphism was associated with Alzheimer’s disease in a large Korean population (Y. Kim et al., 2017). Additionally, mutations in another pro-fusion factor, MSTO1, have been recently associated with increased mitochondrial fragmentation, myopathy and ataxia (Gal et al., 2017; Nasca et al., 2017), providing additional support for the important role for mitochondrial dynamics in disease.

Evidence for the role of imbalanced mitochondrial dynamics in neurological disorders

Many of the diverse human diseases that are associated with aberrant mitochondrial structure and function have been recapitulated in genetic models. In neurons, mitochondrial dynamics support energy production and calcium buffering at synapses through directed and regulated transport mechanisms (Flippo and Strack, 2017). Cerebellar knockout of DNM1L in post-mitotic cells resulted in mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal degeneration, leading to an age-related loss of motor coordination (Kageyama et al., 2012). Similarly, loss of Mfn2 in cerebellar neurons leads to dendrite degeneration and cell death (Chen et al., 2007). These models highlight not only the central importance of mitochondrial dynamics in disease, but also their potential as a therapeutic target. Abnormal, fragmented mitochondria are observed in neurodegenerative disease models with diverse genetic and environmental causes, including Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Park et al., 2018), Huntington’s disease (HD) (Reddy, 2014), Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Kandimalla and Reddy, 2016) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Smith et al., 2017). Several lines of clinical evidence support the hypothesis that mitochondrial division activity predominates over fusion activity in neurodegenerative disease. First, increased Drp1 expression and reduced Mitofusin and Opa1 mRNA and protein levels have been reported in samples obtained from the brain tissue of patients with AD (Manczak et al., 2011) and HD (Kim et al., 2010). Drp1 interactions with tau (Manczak and Reddy, 2012) and mutant huntingtin (Song et al., 2011) both stimulated its enzymatic activity. Consistent with a role in disease pathology, enhanced interactions between Drp1 and huntingtin or tau were observed in human patients with HD (Shirendeb et al., 2012) and AD (Manczak and Reddy, 2012), respectively. Finally, reduced levels of Mitofusin and Opa1 are also correlated with symptom onset and disease progression in HD (Kim et al., 2010) and ALS (Liu et al., 2013). Therefore, unbalanced mitochondrial fusion and division likely contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular degeneration in these diseased states.

Genetic approaches to decrease Drp1 expression or activity, and therefore increase mitochondrial connectivity, have been applied to a number of neurodegenerative disease models (Table 1). For example, expression of a dominant negative variant of Drp1 by neuronal adenovirus injection successfully reduced dopaminergic neuron degeneration in both genetic and environmental PD mouse models (Rappold et al., 2014). Reduction of Drp1 levels by crossing Drp1+/− mice with genetic mouse models of AD also reduced mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration (Kandimalla et al., 2016; Manczak et al., 2016). Inhibition of Drp1 phosphorylation (Kim et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2015) was also protective against neurodegeneration in an AD model, likely due to reduced Drp1 recruitment to mitochondria. These data highlight that aberrant mitochondrial structure and function contributes to multiple types of neuronal dysfunction and indicate that reduced Drp1 expression or activity are both appealing therapeutic approaches.

Table 1.

Mitochondrial dynamics in disease models and therapeutic approaches.

| Disease Model | Reference(s) | Mitochondrial morphology | Cell type | Genoty pe | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodegenerative disease | ||||||

| Dominant optic atrophy (DOA) | Sarzi et al., 2018 | fragmented | retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) | OPA1 +/delTTAG | AAV injection of WT Opa1 | attenuated loss of RGCs in DOA model |

| Parkinson’s disease (PD) | Rappold et al., 2014 | dopaminergic neurons | PINK1−/−; WT (MPTP-induced) | AAV injection of dominant negative Drp1 | restored mitochondrial shape; reduces dopaminergic degeneration | |

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | Manczak et al., 2016 | ubiquitous | Tg2576, APP variant | Heterozygous Drp1 knockout | improved mitochondrial function; reduced neuronal death | |

| Kandimalla et al., 2016 | neurons | Tau P301L | Heterozygous Drp1 knockout | improved mitochondrial function; reduced neuronal death | ||

| Cardiac dysfunction | ||||||

| Cardiomyopathy, heart failure | Wai et al., 2015 | fragmented | cardiomyocytes | YME1L−/− | Concomitant deletion of OMA1 | improved mitochondrial morphology and cardiac function |

| Chen et al., 2015 | heterogenous shape and abundance | ubiquitous | MFF−/− | Concomitant deletion of MFN1 | rescued mitochondrial & cardiac function; restored lifespan defects | |

| Song et al., 207 | elongated in Drp1−/−; fragmented in Mfn1−/−, Mfn2−/− | cardiomyocytes | DNM1L−/− or MFN1−/, MFN2−/− | Triple knockout: DNM1L, MFN1, MFN2 | improved cardiac function partially, but created distinct abnormalities; early senescence instead of death | |

| Ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury | Hall et al., 2016 | fragmented | cardiomyocytes | WT | Deletion of MFN1 and MFN2 | reduced cell death/increased survival |

| Papanicolau et al., 2011 | cardiomyocytes | Deletion of MFN2 | improved cardiac performance; protection from cell death | |||

| Gall et al., 2015 | proximal tubules (kidney) | Deletion of MFN2 | improved recovery and survival after renal IR injury | |||

| Metabolic dysfunction | ||||||

| Diet-induced insulin resistance | Boutant et al., 2017 | fragmented | adipose tissue | WT | Deletion of MFN2 | protected against high fat induced insulin-resistance |

| Kulkarni et al., 2016 | liver | Deletion of MFN1 | protected against high fat induced insulin-resistance; increased complex I abundance | |||

| Diabetic nephropathy | Ayanga et al., 2016 | podocytes (kidney) | Deletion of DNM1L | rescued mitochondrial fragmentation; protected against mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic neuropathy | ||

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | Yamada et al., 2018 | accumulation of giant mitochondria | liver | Deletion of OPA1 | reduces giant mitochondria; attenuated liver damage in fatty livers |

Evidence for the role of imbalanced dynamics in cardiac dysfunction

As with neurons, the high metabolic demand of the heart requires balanced mitochondrial dynamics for normal function. Heart failure in humans is associated with reduced protein levels of Mfn2 and Opa1 (Ahuja et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2009). Levels of Mfn1, Mfn2, Opa1 and Drp1 are also altered in hypertrophy-related heart failure (Fang et al., 2007; Javadov et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2014). In a screen for genetic modifiers of congestive heart failure, a mutation in DNM1L was associated with dilated inherited cardiomyopathy and impaired Drp1 disassembly (Ashrafian et al., 2010; Cahill et al., 2016). Additionally, several conditional knockouts of DNM1L in the mouse heart caused mitochondrial elongation and impaired mitochondrial function, which was associated with reduced cardiac function and survival (Ikeda et al., 2015; Ishihara et al., 2015; Kageyama et al., 2014). Mitochondrial division is also required for cardiac function after development. Cardiac-specific loss of Drp1 in adult mice caused mitochondrial elongation and dysfunction, similar to the mitochondrial defects observed in embryonic DNM1L knockouts (Ikeda et al., 2015). Impaired mitochondrial fusion activity is also detrimental to cardiac function, as heart-specific knockdown (Dorn et al., 2011) and knockout (Chen et al., 2011) of the outer membrane fusion DRP led to mitochondrial fragmentation and cardiac dysfunction in flies and mice, respectively. Conditional knockout of the Mitofusins in adult mouse hearts resulted in similar cellular dysfunction and led to rapidly progressive cardiomyopathy (Chen et al., 2011). Cardiac dysfunction was also reported in Opa1+/− mice (Chen et al., 2012) and in a mouse model harboring a cardiac-specific deletion of the Opa1-processing protease, YME1L, where improper Opa1 processing was associated with cardiomyopathy and heart failure (Wai et al., 2015). Interestingly, concomitant deletion of Oma1 in the YME1L mutants rebalanced Opa1 processing and led to improved mitochondrial morphology and cardiac function (Wai et al., 2015). Together, these models illustrate the important role of mitochondrial fusion and division in heart development and function.

The importance of balanced mitochondrial dynamics in cardiac function is supported by genetic mouse models. The cardiomyopathy-related defects in Mff knockout mice can be significantly rescued by concomitant deletion of MFN1 (Chen et al., 2015). Similarly, the cardiac defects in a triple knockout mouse (Mfn1−/−, Mfn2−/−, Drp1−/−) are unique and less severe than any of the single knockouts (Song et al., 2017). The relationship between mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics is unique in the heart. Specifically, loss of mitochondrial division was associated with increased mitophagy despite the highly connected network, while the fragmented mitochondria that result from loss of mitochondrial fusion were resistant to mitophagic turnover. These data suggest that in some tissues, balanced fusion and division is more important to maintain function than the absolute rate of fusion or division. The protective effects observed in these models supports the argument that targeting the balance of mitochondrial dynamics may be a promising therapeutic approach (Table 1).

While loss of fusion activity is generally associated with mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunction, some models of MFN1 and/or MFN2 genetic ablation exhibit protective effects (Table 1). Cardiac-specific knockout of one or both Mitofusins was associated with attenuated cell death and increased survival during ischemic-reperfusion (IR) injury (Hall et al., 2016; Papanicolaou et al., 2011). Additionally, conditional knockdown of Mfn2 in the proximal tubules of the kidney was protective against cell death after renal IR injury (Gall et al., 2015; 2012). It could be that the loss of Mfn2 can be protective in the short-term due to increased cellular proliferation (Chen et al., 2014), while prolonged reduction of Mfn2 may lead to more serious cardiomyopathy defects due to a lack of fusion (Gall et al., 2015).

Evidence for the role of imbalanced dynamics in metabolic disease

Genetic approaches have also addressed imbalanced mitochondrial dynamics associated with metabolic sensing and signaling in type 2 diabetes (Kelley et al., 2002; Toledo et al., 2006; Williams and Caino, 2018) (Table 1). MFN2 deletion in adipose tissue was protective against diet-induced insulin resistance (Boutant et al., 2017) and mice with a liver specific deletion of MFN1 were protected against high fat induced insulin resistance (Kulkarni et al., 2016). Interestingly, loss of Drp1 in podocytes reduced diabetic nephropathy in mice that had already developed diabetes (Ayanga et al., 2016). In a distinct disease model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, liver-specific knockout of OPA1 reduced the formation of giant mitochondria and partially rescued defects associated with a fatty liver (Yamada et al., 2018).

In sum, the genetic models discussed demonstrate the critical role of balanced mitochondrial dynamics during development and through adulthood. Consequently, aberrant mitochondrial dynamics are associated with tissue dysfunction in a wide range of human diseases. In these model systems, genetic approaches that re-establish balanced fusion and division indicate that genetic therapy may be a viable approach to improve patient health in disease.

Altering mitochondrial division activity with small molecules

Mitochondrial dynamics have also been rebalanced through the application of small molecules that alter Drp1 activity. In diseases characterized by excessive mitochondrial fragmentation, small molecule inhibition of Drp1 has effectively improved function and cell survival in several diverse disease models (Table 2). There appear to be two common factors that improve upon restoration of mitochondrial connectivity: mitochondrial metabolic function and reduced susceptibility to cell death signals. It is likely that by impacting these core mitochondrial functions, disease progression is slowed, and health is improved.

Table 2.

Small molecules altering mitochondrial fusion and division.

| Drug Name | Reference(s) [discovery, creation] | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Division | ||

| Dynasore | Macia et al., 2006 | Inhibited GTPase activity of Dynamin 1, Dynamin 2, Drp1 |

| mdivi-1 | Cassidy-Stone et al., 2008, Bordt et al., 2017 | Inhibited Drp1 (18267088) and/or Complex I (28350990) |

| P110 | Qi et al., 2013 | Inhibited GTPase activity of Drp1 and its interaction with Fis1 |

| TAT-Drp1SpS | Yan et al., 2015 | Blocked Drp1 phosporylation by GSK3B |

| 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxamide compounds | Mallat et al., 2018 | Inhibited GTPase activity of Drp1 |

| Fusion | ||

| MP1Gly | Franco et al., 2016 | Stimulated Mitofusins |

| MP2Gly | Franco et al., 2016 | Inhibited Mitofusins |

| Chimera BA/I | Rocha et al., 2018 | Stimulated Mfn2 |

| SAMβA | Ferreira et al., 2019 | Inhibited interaction between Mfn1 and βIIPKC |

| BGP-15 | Szabo et al., 2018 | Stimulated GTPase activity and assembly of Opa1; activated diverse other signaling pathways |

| S3 | Yue et al., 2014 | Inhibited USP30, increased non-degradative Mitofusin ubiquitination |

| Leflunomide | Miret-Casals et al., 2018 | Inhibited dihydorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) or Complex III, increased Mitofusin levels |

| M1 | Wang et al., 2012 | Increased levels of ATP5A/B |

Both the enzymatic activity of Drp1 and its recruitment to mitochondria have been modulated by small molecules. To date, several biochemical screens for enzymatic inhibitors of Drp1 have been performed. Dynasore was an early drug identified that inhibited GTPase activity of dynamin and Drp1, but not the related DRP, MxA, or the small GTPase, Cdc42 (Macia et al., 2006). While Dynasore is not a viable therapeutic given the non-specific inhibition of both Drp1 and dynamin, its discovery established that the DRP family can be effectively targeted by small molecules. Soon after Dynasore was characterized, mdivi-1 was identified as a specific inhibitor of the yeast mitochondrial division protein, Dnm1 (Cassidy-Stone et al., 2008). Unlike Dynasore, mdivi-1 specifically inhibited the GTPase activity of Dnm1 and abolished its assembly in vitro. Furthermore, treatment of Cos7 cells with mdivi-1 resulted in mitochondrial elongation and enhanced resistance to apoptotic stimuli, which are both consistent with the conclusion that the drug inhibited mammalian Drp1 activity. While mdivi-1 has been utilized extensively in various disease models, the mechanism of mdivi-1 activity has recently been challenged (Bordt et al., 2017). This group reported that mdivi-1 did not elongate mitochondria in cell culture, but instead inhibited complex I activity and ROS generation, which could explain its therapeutic effects. The reason for the different effects on mitochondrial structure in various studies is not clear. Further characterization of mdivi-1 is required to determine its mechanism of action and its potential as a therapeutic to treat human disease.

Despite the controversial mechanism of mdivi-1, its direct or indirect effects on mitochondrial morphology can be examined to infer how changes in mitochondrial structure and function can alter disease outcomes. Therefore, we only discuss studies in which mdivi-1 has been specifically reported to restore mitochondrial morphology in disease models associated with excessive mitochondrial division. In neurons, several lines of evidence indicate that mdivi-1 is a promising therapeutic to attenuate neuronal cell death in neurodegenerative disease and neurotoxicity models. Both apoptosis and mitophagy were inhibited by mdivi-1 treatment using in vitro genetic and environmental PD models (Alaimo et al., 2014; Cui et al., 2010; Solesio et al., 2012). Similarly, mdivi-1 treatment of in vitro neuronal models for AD restored the mitochondrial dynamic balance and alleviated mitochondrial dysfunction associated with excessive amyloid beta-induced autophagy (Gan et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016). Furthermore, mouse models of PD and AD showed improved behavior outcomes and reduced neurodegeneration following mdivi-1 treatment (Bido et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017), suggesting that the functional benefits of mdivi-1 treatment extend beyond the cellular level. While the mechanism of neurodegeneration in the peripheral neuropathy hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) is not well understood, cells derived from HSP patients had dysfunctional mitochondria, characterized by the prevalence of few, short, mitochondria with low membrane potential (Denton et al., 2018). Treatment with mdivi-1 suppressed major disease symptoms in these neurons, including neurite growth defects and neuronal cell death (Denton et al., 2018). Stress-induced neuronal apoptosis has also been observed in pediatric anesthesia models and cell death was alleviated by mdivi-1 treatment (Gao et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2017; F. Xu et al., 2016). Application of mdivi-1 also reduced neuronal death after prolonged seizure activity (Kim and Kang, 2017), traumatic brain injury (Wu et al., 2018), and spinal injury (X. Chen et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2017). Finally, the cognitive dysfunction (Zhao et al., 2018) and neuronal death caused by disrupted glucose regulation in diabetic individuals (Huang et al., 2015; S. Kim et al., 2017) can be partially rescued by mdivi-1 treatment. Together, these studies suggest that improved mitochondrial function improves disease outcome in a wide range of neurodegenerative disorders.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a common feature of a range of cardiovascular diseases and therefore mitochondrial dynamics represent a potentially powerful therapeutic target (Brown et al., 2017). Consistent with this, mdivi-1 partially rescued cardiac dysfunction in diverse mouse cardiomyopathy models, likely due to reduced autophagy (Z. Chen et al., 2018) and apoptosis (Alam et al., 2018; Qi et al., 2018). Mitochondrial fragmentation is associated with cell death during ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury and mdivi-1 has been reported to prevent excessive cell death of both cardiac and neuronal cells during IR injuries in several model systems. In cardiac stem cells (Rosdah et al., 2017), ex vivo hearts (Sharp et al., 2014) and an in vivo mouse model (Maneechote et al., 2018), mdivi-1 treatment before, during or after cardiac IR injury was protective. Following stroke or cardiac arrest in mouse models, neuronal death and associated neurological dysfunction occur, but were rescued when mdivi-1 treatment was administered immediately after injury (Fan et al., 2017; P. Wang et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2017).

Notably, pretreatment with mdivi-1 before renal IR injury exacerbated cell death due to impaired mitophagy (Li et al., 2018), indicating that this approach is not universally effective. Further characterization of mdivi-1 and its activity in IR are needed to clarify both the drug mechanism and how it impacts the response to IR in different tissues. Nevertheless, these results suggest that modulating mitochondrial structure and function in acute injury is a viable approach to improve the outcome.

In addition to diseases and stress responses where mitochondrial dysfunction have been clearly implicated, mdivi-1 has been administered in a wide variety of other disorders. For example, mdivi-1 treatment has been utilized in treating bone (H. Wang et al., 2018) and muscle atrophy (Troncoso et al., 2014), acetaminophen-induced liver injury (Gao et al., 2017), cisplatin-induced kidney injury (Liu et al., 2018), cisplatin-induced hair cell loss (Vargo et al., 2017) and cocksackie virus B viral infections (Sin et al., 2017). Mdivi-1 has also been reported to have anti-inflammatory effects in glial cells (Park et al., 2013), osteoblasts (Zhang et al., 2017) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Hecker et al., 2018). In addiction therapy, mdivi-1 was shown to blunt cocaine-seeking behavior in rats (Chandra et al., 2017). Therefore, the range of disease states that could be potentially treated by targeting mitochondrial dynamics is very broad.

Another small molecule developed to disrupt mitochondrial division activity is P110, a small peptide that specifically blocks the interaction between Drp1 and Fis1 (Qi et al., 2013). Although some Drp1 was localized to mitochondria due to interactions with other receptors, treatment of cells with P110 significantly reduced the mitochondrial population of Drp1. Consistent with a role for mitochondrial division in promoting apoptotic cell death, P110 treatment protected against cell death by inhibiting the mitochondrial recruitment of pro-apoptotic proteins, including p53, Bax and PUMA (Filichia et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2014). P110 inhibition of mitochondrial division has also improved function in many models of neurodegenerative diseases, similar to mdivi1. P110 reduced mitochondrial fragmentation and cell death in primary and iPSC-derived PD and HD patient neurons (Guo et al., 2013; Qi et al., 2013; Su and Qi, 2013). P110 treatment also prevented neuronal degeneration and motor dysfunction in mouse models for PD (Filichia et al., 2016) and HD (Guo et al., 2013). Similarly, P110 slowed neuronal degeneration and demyelination in multiple sclerosis (Luo et al., 2017). Interestingly, an enhanced interaction between Drp1 and Fis1 was observed in patient-derived fibroblasts and neurons treated with amyloid beta, a model of AD (Joshi et al., 2018a). Consistent with a pathological role for this interaction, P110 treatment of mouse models for AD rescued mitochondrial function and cognitive defects (Joshi et al., 2018a). P110 treatment also improved locomotion and muscle structure in a mouse model for ALS (Joshi et al., 2018b). Importantly there were no observable effects on a wild type mouse, suggesting that P110 may selectively inhibit pathological division while maintaining other normal physiological division activity (Joshi et al., 2018b). Notably, both the neuronal and cardiac defects in a mouse model for HD can be ameliorated by P110 (Joshi et al., 2019). Consistent with this, P110 has also been described as a possible treatment for other cardiac dysfunction, including IR injury. In rat hearts, treatment with P110 after IR injury improved cardiac structure and attenuated some mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunction (Disatnik et al., 2013; Tian et al., 2017).

Together, studies assessing the application of P110 and mdivi-1 emphasize the potential of Drp1 as a therapeutic target (Table 2). Novel Drp1 GTPase inhibitors continue to be identified, highlighted by a recent study that identified compounds that inhibited Drp1 assembly and were able to restore mtDNA copy numbers in Mfn1−/− cells (Mallat et al., 2018). However, significantly more work is required to understand how small molecule modulation of Drp1 activity by mdivi-1, P110 or other drugs modulates disease outcomes. Moving forward, the design of effective therapeutics that target mitochondrial division will rely on improved understanding of the mechanism of mitochondrial division in normal and diseased states.

Altering mitochondrial fusion activity with small molecules

Chemical therapeutic approaches that target the activity and regulation of the mitochondrial fusion machines can also rebalance aberrant mitochondrial dynamics in cells (Table 2). To our knowledge, the first small molecules that have been shown to directly modulate Mitofusin activity were small peptides corresponding to different regions of the Mitofusins that either enhanced (MP1Gly) or inhibited (MP2Gly) mitochondrial fusion when added to cells in culture (Franco et al., 2016). Using a cell culture model of CMT2A, a small molecule Mitofusin agonist (Chimera B-A/I) restored mitochondrial morphology and motility by activating wild-type Mitofusin (Rocha et al., 2018). These data establish that either small peptides or small molecules can directly modulate the activity of the mitochondrial fusion DRPs.

Another drug that enhanced mitochondrial fusion activity was recently reported to reduce cardiac apoptotic cell death in vivo. βIIPKC contributes to heart failure through phosphorylation of Mfn1, which increased its turnover and impaired mitochondrial fusion. The novel small peptide SAMβA inhibited the interaction of Mfn1 with βIIPKC, which in turn improved mitochondrial and cardiac function in a rat model for heart failure (Ferreira et al., 2019).

The GTPase activity and self-assembly of Opa1 has been modulated by the small molecule BGP-15. BGP-15 prevented mitochondrial fragmentation in lung epithelial cells treated with hydrogen peroxide (Szabo et al., 2018). However, the cytoprotective activity of BGP-15 also required Mfn1, Mfn2 and protein kinase B (AKT), suggesting that the mechanism of action is potentially more complex. Nevertheless, this suggests that modulating mitochondrial fusion could help prevent reactive oxygen species-induced cell death.

Altering the post-translational modification state of Mitofusins may be another way to alter mitochondrial fusion activity. USP30 is a deubiquitinase that removes ubiquitin from Mitofusin, which is associated with increased mitochondrial fusion and decreased mitophagy (Hou et al., 2017). Treatment of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with the small molecule 15-oxospiramilactone (S3) led to increased mitochondrial connectivity and the retention of nondegradative ubiquitin modifications on Mfn1 and Mfn2 (Yue et al., 2014) through interactions with the active site of USP30 that block its deubiquitinase activity. Treatment with S3 was associated with increased mitochondrial fusion activity, ATP production and oxidative capacity of MEFs. In adult cardiomyocytes, S3 treatment was also associated with increased steady-state mitochondrial connectivity; however, cellular respiration was unchanged suggesting that the effects may be cell type specific (Zhang et al., 2017).

Screens for compounds that disrupt the balance of mitochondrial dynamics have identified other small molecules that may directly or indirectly increase mitochondrial fusion activity. Recent work established that increased pyrimidine biosynthesis correlated with increased mitochondrial connectivity and cellular resistance to stress-induced apoptosis (Miret-Casals et al., 2018). Pyrimidine biosynthesis was promoted by chemical inhibition of either dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) or Complex III, which upregulated both Mfn1 and Mfn2 mRNA levels. The resulting increased Mitofusin protein expression corresponded to increased mitochondrial fusion and resistance of these cells to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis. Therefore, to increase mitochondrial connectivity in disease states, mitochondrial fusion could be augmented indirectly by molecules that moderately increase protein expression levels.

In another screen to identify small molecules that alter mitochondrial morphology, hydrazone M1 (M1) restored mitochondrial fusion in Mfn1 and Mfn2 knockout MEFs (D. Wang et al., 2012). While the mechanism of this drug is not well understood, M1 treatment increased protein expression of ATP5A/B, subunits of the ATP synthase complex, and protected cells against apoptosis. In primary hippocampal neurons exposed to β-amyloid peptide, which has been shown to cause mitochondrial fragmentation, mitochondrial connectivity was restored and oxidative damage was inhibited following M1 treatment (Hung et al., 2018). M1 treatment is also being explored as an immune therapy because changes in mitochondrial structure have been shown to drive immune cell function (Buck et al., 2016; Du et al., 2018; Rambold and Pearce, 2018). For instance, the impaired clearance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is associated with high levels of cholesterol and altered mitochondrial shape (Kaul et al., 2004) and clearance was improved by treating cholesterol-inhibited macrophages with M1 (Asalla et al., 2017). High cholesterol levels can similarly impair cellular function in pancreatic beta cells and M1 treatment restored mitochondrial morphology in culture and improved glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (Asalla et al., 2016). Although the mechanism of M1 action remains unclear, these data suggest that targeting the mitochondrial fusion machinery is a viable approach to treat a range of human diseases.

Related therapeutic approaches

Mitochondrial transport and disease

While we have emphasized therapeutic approaches that target the mitochondrial fusion and division DRPs, mitochondrial trafficking could also be modulated to improve cellular function in disease. Normal neuronal function requires mitochondrial transport from the cell body to the presynaptic terminal (Course and Wang, 2016; Devine and Kittler, 2018). Mitochondrial fusion (Misko et al., 2010) and division (Nemani et al., 2018) may influence mitochondrial trafficking, suggesting significant interplay between the different mitochondrial dynamic pathways. Indeed, aberrant mitochondrial accumulation is often observed in the cell body of neuronal models of neurodegeneration, including CMT2A, consistent with trafficking defects (Baloh et al., 2007; Fissi et al., 2018). Mitochondria are distributed by directed and regulated transport on microtubules by kinesin and dynein motors (Pilling et al., 2006). Motor proteins attach to Miro½ GTPases on the mitochondrial outer membrane through the adaptor proteins TRAK½ (Schwarz, 2013). Deletion of MIRO1 in mouse neurons phenocopied human upper motor neuron disease due to mitochondrial transport and distribution defects (Nguyen et al., 2014). Similarly, loss of Miro1 in mature, adult neurons caused loss of dendrite complexity and reduced neuronal survival (López-Doménech et al., 2016). Loss of Miro has also been reported in AD and ALS (Kay et al., 2018), suggesting that mitochondrial transport is altered in diverse neurodegenerative diseases.

Miro accumulation due to dysregulated turnover is observed in Parkinson’s disease (Hsieh et al., 2016; Shaltouki et al., 2018). In healthy cells, PINK1, Parkin and LRRK2 integrate mitochondrial function and transport by identifying dysfunctional organelles and promoting Miro degradation (Hsieh et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2011). Like Miro, altered activity of PINK1, Parkin and LRRK2 are also associated with PD (Hernandez et al., 2016). Importantly, reduction of Miro in a fly PD model rescued mitochondrial movement and neurodegeneration (Hsieh et al., 2016; Shaltouki et al., 2018).

Mitochondria-ER contact sites

Defective mitochondrial distribution and dynamics also affect mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum (mito-ER) contacts, which have been implicated in Ca2+ and ROS signaling between the organelles (Csordas et al., 2018). Although the biology that occurs at these sites is extensive and likely to be tissue specific, altered calcium signaling at mito-ER contacts is associated with neuronal degeneration in a fly model for PD (K.-S. Lee et al., 2018). Furthermore, defects in lipid synthesis, lipid droplet regulation and mito-ER contact formation were reported in patient-derived CMT2A cells (Larrea et al., 2019). Therefore, proteins at mito-ER contact sites, such as Mfn2 and VDAC, represent additional potential targets to modulate mitochondrial dynamics and function in diseased states (Tubbs and Rieusset, 2017).

Conclusion

Many lines of evidence indicate that aberrant mitochondrial structure and function contribute to cellular dysfunction, cell death and disease pathology. Imbalanced mitochondrial dynamics are observed in a range of diseases including neurodegenerative and cardiac disorders, all despite divergent genetic and environmental causes. Consistent with an important role for mitochondrial dynamics, mutations in the genes encoding the mitochondrial fusion and division proteins are associated with developmental defects and neurodegeneration. When fragmented mitochondrial networks are a component of disease pathophysiology, increased fusion or decreased division activity would both augment mitochondrial connectivity in these cells and would be expected to protect against deteriorating function. While excessive mitochondrial connectivity is less common in diseased states, it is observed in patients with mutations in genes encoding mitochondrial division proteins. These patients could be treated by attenuating mitochondrial fusion or increased mitochondrial division. While the causal relationship between imbalanced mitochondrial dynamics and disease progression remains unclear in many models, it is apparent that therapies restoring balanced mitochondrial dynamics are a promising tool to reduce cellular dysfunction, tissue degeneration and functional and behavioral outcomes. As with all disease interventions, therapeutics targeting mitochondria will face delivery and specificity challenges to ameliorate pathological symptoms without inducing negative side effects. Nevertheless, both genetic and chemical approaches implemented in model systems that have rebalanced mitochondrial dynamics, the restored mitochondrial structure and function alleviates disease-associated symptoms. Research focused on dissecting the mechanism of mitochondrial fusion and division as well as understanding the integration of these processes with other cellular pathways will be essential aspects of developing effective therapeutics.

Dynamic processes contributing to changes in mitochondrial structure are bolded. The proteins or protein-protein interactions that mediate these processes are noted inside the circle. Mitochondria are shaded to illustrate changes in membrane potential that may occur during mitochondrial fusion and division (black indicates dysfunctional mitochondria and light grey indicates high membrane potential).

Mitochondrial division supports distribution of mitochondria throughout the cell, as well as the selective degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria by mitophagy. Mitochondrial outer membrane fusion occurs first, but is coupled to mitochondrial inner membrane fusion, which allows for content mixing and promotes the formation of a connected, homogeneous network.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahuja P, Wanagat J, Wang Z, Wang Y, Liem DA, Ping P, Antoshechkin IA, Margulies KB, Maclellan WR, 2013. Divergent mitochondrial biogenesis responses in human cardiomyopathy. Circulation 127, 1957–1967. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaimo A, Gorojod RM, Beauquis J, Muñoz MJ, Saravia F, Kotler ML, 2014. Deregulation of mitochondria-shaping proteins Opa-1 and Drp-1 in manganese-induced apoptosis. PLoS ONE 9, e91848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam S, Abdullah CS, Aishwarya R, Miriyala S, Panchatcharam M, Peretik JM, Orr AW, James J, Robbins J, Bhuiyan MS, 2018. Aberrant Mitochondrial Fission Is Maladaptive in Desmin Mutation-Induced Cardiac Proteotoxicity. J Am Heart Assoc 7. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavi MV, Fuhrmann N, Nguyen HP, Yu-Wai-Man P, Heiduschka P, Chinnery PF, Wissinger B, 2009. Subtle neurological and metabolic abnormalities in an Opa1 mouse model of autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Experimental Neurology 220, 404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand R, Wai T, Baker MJ, Kladt N, Schauss AC, Rugarli E, Langer T, 2014. The i-AAA protease YME1L and OMA1 cleave OPA1 to balance mitochondrial fusion and fission. J. Cell Biol. 204, 919–929. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201308006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GR, Wardell SE, Cakir M, Yip C, Ahn Y-R, Ali M, Yllanes AP, Chao CA, McDonnell DP, Wood KC, 2018. Dysregulation of mitochondrial dynamics proteins are a targetable feature of human tumors. Nat Commun 9, 1677. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04033-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, 2013. Mitochondrial dynamics--mitochondrial fission and fusion in human diseases. N. Engl. J. Med 369, 2236–2251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1215233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asalla S, Girada SB, Kuna RS, Chowdhury D, Kandagatla B, Oruganti S, Bhadra U, Bhadra MP, Kalivendi SV, Rao SP, Row A, Ibrahim A, Ghosh PP, Mitra P, 2016. Restoring Mitochondrial Function: A Small Molecule-mediated Approach to Enhance Glucose Stimulated Insulin Secretion in Cholesterol Accumulated Pancreatic beta cells. Sci Rep 6, 27513. doi: 10.1038/srep27513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asalla S, Mohareer K, Banerjee S, 2017. Small Molecule Mediated Restoration of Mitochondrial Function Augments Anti-Mycobacterial Activity of Human Macrophages Subjected to Cholesterol Induced Asymptomatic Dyslipidemia. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7, 439. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafian H, Docherty L, Leo V, Towlson C, Neilan M, Steeples V, Lygate CA, Hough T, Townsend S, Williams D, Wells S, Norris D, Glyn-Jones S, Land J, Barbaric I, Lalanne Z, Denny P, Szumska D, Bhattacharya S, Griffin JL, Hargreaves I, Fernandez-Fuentes N, Cheeseman M, Watkins H, Dear TN, 2010. A mutation in the mitochondrial fission gene Dnm1l leads to cardiomyopathy. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayanga BA, Badal SS, Wang Y, Galvan DL, Chang BH, Schumacker PT, Danesh FR, 2016. Dynamin-Related Protein 1 Deficiency Improves Mitochondrial Fitness and Protects against Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 27, 2733–2747. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015101096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach D, Pich S, Soriano FX, Vega N, Baumgartner B, Oriola J, Daugaard JR, Lloberas J, Camps M, Zierath JR, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Wallberg-Henriksson H, Laville M, Palacín M, Vidal H, Rivera F, Brand M, Zorzano A, 2003. Mitofusin-2 determines mitochondrial network architecture and mitochondrial metabolism. A novel regulatory mechanism altered in obesity. J Biol Chem 278, 17190–17197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212754200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloh RH, Schmidt RE, Pestronk A, Milbrandt J, 2007. Altered axonal mitochondrial transport in the pathogenesis of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease from mitofusin 2 mutations. J Neurosci 27, 422–430. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4798-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban T, Ishihara T, Kohno H, Saita S, Ichimura A, Maenaka K, Oka T, Mihara K, Ishihara N, 2017. Molecular basis of selective mitochondrial fusion by heterotypic action between OPA1 and cardiolipin. Nat. Cell Biol 19, 856–863. doi: 10.1038/ncb3560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbullushi K, Abati E, Rizzo F, Bresolin N, Comi GP, Corti S, 2019. Disease Modeling and Therapeutic Strategies in CMT2A: State of the Art. Mol. Neurobiol 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12035-019-1533-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsakoulia M, Pyle A, Troncoso-Chandía D, Vial-Brizzi J, Paz-Fiblas MV, Duff J, Griffin H, Boczonadi V, Lochmüller H, Kleinle S, Chinnery PF, Grünert S, Kirschner J, Eisner V, Horvath R, 2018. A novel mechanism causing imbalance of mitochondrial fusion and fission in human myopathies. Hum Mol Genet 27, 1186–1195. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso V, Marchesan E, Peggion C, Chakraborty J, Stockum, von S, Giacomello M, Ottolini D, Debattisti V, Caicci F, Tasca E, Pegoraro V, Angelini C, Antonini A, Bertoli A, Brini M, Ziviani E, 2018. Regulation of ER-mitochondria contacts by Parkin via Mfn2. Pharmacol. Res. 138, 43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet AM, Delerue T, Millet AM, Moulis MF, David C, Daloyau M, Arnauné-Pelloquin L, Davezac N, Mils V, Miquel MC, Rojo M, Belenguer P, 2016. Mitochondrial fusion/fission dynamics in neurodegeneration and neuronal plasticity. Neurobiol. Dis 90, 3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bido S, Soria FN, Fan RZ, Bezard E, Tieu K, 2017. Mitochondrial division inhibitor-1 is neuroprotective in the A53T-α-synuclein rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep 7, 7495. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07181-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleazard W, McCaffery JM, King EJ, Bale S, Mozdy A, Tieu Q, Nunnari J, Shaw JM, 1999. The dynamin-related GTPase Dnm1 regulates mitochondrial fission in yeast. Nat. Cell Biol 1, 298–304. doi: 10.1038/13014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordt EA, Clerc P, Roelofs BA, Saladino AJ, Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V, Cherok E, Khalil A, Yadava N, Ge SX, Francis TC, Kennedy NW, Picton LK, Kumar T, Uppuluri S, Miller AM, Itoh K, Karbowski M, Sesaki H, Hill RB, Polster BM, 2017. The Putative Drp1 Inhibitor mdivi-1 Is a Reversible Mitochondrial Complex I Inhibitor that Modulates Reactive Oxygen Species. Dev. Cell 40, 583–594.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutant M, Kulkarni SS, Joffraud M, Ratajczak J, Valera-Alberni M, Combe R, Zorzano A, Cantó C, 2017. Mfn2 is critical for brown adipose tissue thermogenic function. EMBO J 36, 1543–1558. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt T, Cavellini L, Kühlbrandt W, Cohen MM, 2016. A mitofusin-dependent docking ring complex triggers mitochondrial fusion in vitro. Elife 5, 36634. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Perry JB, Allen ME, Sabbah HN, Stauffer BL, Shaikh SR, Cleland JGF, Colucci WS, Butler J, Voors AA, Anker SD, Pitt B, Pieske B, Filippatos G, Greene SJ, Gheorghiade M, 2017. Expert consensus document: Mitochondrial function as a therapeutic target in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 14, 238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck MD, O’Sullivan D, Klein Geltink RI, Curtis JD, Chang C-H, Sanin DE, Qiu J, Kretz O, Braas D, van der Windt GJW, Chen Q, Huang SC-C, O’Neill CM, Edelson BT, Pearce EJ, Sesaki H, Huber TB, Rambold AS, Pearce EL, 2016. Mitochondrial Dynamics Controls T Cell Fate through Metabolic Programming. Cell 166, 63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman JL, Pickles S, Wang C, Sekine S, Vargas JNS, Zhang Z, Youle AM, Nezich CL, Wu X, Hammer JA, Youle RJ, 2017. Mitochondrial fission facilitates the selective mitophagy of protein aggregates. J. Cell Biol 216, 3231–3247. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201612106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burté F, Carelli V, Chinnery PF, Yu-Wai-Man P, 2015. Disturbed mitochondrial dynamics and neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 11, 11–24. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill TJ, Leo V, Kelly M, Stockenhuber A, Kennedy NW, Bao L, Cereghetti GM, Harper AR, Czibik G, Liao C, Bellahcene M, Steeples V, Ghaffari S, Yavari A, Mayer A, Poulton J, Ferguson DJP, Scorrano L, Hettiarachchi NT, Peers C, Boyle J, Hill RB, Simmons A, Watkins H, Dear TN, Ashrafian H, 2016. Resistance of dynamin-related protein 1 oligomers to disassembly impairs mitophagy, resulting in myocardial inflammation and heart failure. J Biol Chem 291, 25762–25762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.A115.665695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y-L, Meng S, Chen Y, Feng J-X, Gu D-D, Yu B, Li Y-J, Yang J-Y, Liao S, Chan DC, Gao S, 2017. MFN1 structures reveal nucleotide-triggered dimerization critical for mitochondrial fusion. Nature 542, 372–376. doi: 10.1038/nature21077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carelli V, Musumeci O, Caporali L, Zanna C, La Morgia C, Del Dotto V, Porcelli AM, Rugolo M, Valentino ML, Iommarini L, Maresca A, Barboni P, Carbonelli M, Trombetta C, Valente EM, Patergnani S, Giorgi C, Pinton P, Rizzo G, Tonon C, Lodi R, Avoni P, Liguori R, Baruzzi A, Toscano A, Zeviani M, 2015. Syndromic parkinsonism and dementia associated with OPA1 missense mutations. Ann. Neurol 78, 21–38. doi: 10.1002/ana.24410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy-Stone A, Chipuk JE, Ingerman E, Song C, Yoo C, Kuwana T, Kurth MJ, Shaw JT, Hinshaw JE, Green DR, Nunnari J, 2008. Chemical inhibition of the mitochondrial division dynamin reveals its role in Bax/Bak-dependent mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. Dev. Cell 14, 193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereghetti GM, Costa V, Scorrano L, 2010. Inhibition of Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation and apoptosis by a polypeptide antagonist of calcineurin. Cell Death Differ 17, 1785–1794. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereghetti GM, Stangherlin A, Martins de Brito O, Chang CR, Blackstone C, Bernardi P, Scorrano L, 2008. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 105, 15803–15808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808249105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra R, Engeln M, Schiefer C, Patton MH, Martin JA, Werner CT, Riggs LM, Francis TC, McGlincy M, Evans B, Nam H, Das S, Girven K, Konkalmatt P, Gancarz AM, Golden SA, Iñiguez SD, Russo SJ, Turecki G, Mathur BN, Creed M, Dietz DM, Lobo MK, 2017. Drp1 Mitochondrial Fission in D1 Neurons Mediates Behavioral and Cellular Plasticity during Early Cocaine Abstinence. Neuron 96, 1327–1341.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-R, Blackstone C, 2007. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation of Drp1 regulates its GTPase activity and mitochondrial morphology. J Biol Chem 282, 21583–21587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700083200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-R, Manlandro CM, Arnoult D, Stadler J, Posey AE, Hill RB, Blackstone C, 2010. A lethal de novo mutation in the middle domain of the dynamin-related GTPase Drp1 impairs higher order assembly and mitochondrial division. J Biol Chem 285, 32494–32503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.142430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao Y-H, Robak LA, Xia F, Koenig MK, Adesina A, Bacino CA, Scaglia F, Bellen HJ, Wangler MF, 2016. Missense variants in the middle domain of DNM1L in cases of infantile encephalopathy alter peroxisomes and mitochondria when assayed in Drosophila. Hum Mol Genet 25, 1846–1856. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chan DC, 2017. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Regulating the Unique Phenotypes of Cancer and Stem Cells. Cell Metabolism 26, 39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffin EE, Fraser SE, Chan DC, 2003. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J. Cell Biol 160, 189–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, McCaffery JM, Chan DC, 2007. Mitochondrial fusion protects against neurodegeneration in the cerebellum. Cell 130, 548–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Ren S, Clish C, Jain M, Mootha V, McCaffery JM, Chan DC, 2015. Titration of mitochondrial fusion rescues Mff-deficient cardiomyopathy. J. Cell Biol 211, 795–805. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201507035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Vermulst M, Wang YE, Chomyn A, Prolla TA, McCaffery JM, Chan DC, 2010. Mitochondrial fusion is required for mtDNA stability in skeletal muscle and tolerance of mtDNA mutations. Cell 141, 280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K-H, Dasgupta A, Ding J, Indig FE, Ghosh P, Longo DL, 2014. Role of mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) in controlling cellular proliferation. FASEB J. 28, 382–394. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-230037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K-H, Guo X, Ma D, Guo Y, Li Q, Yang D, Li P, Qiu X, Wen S, Xiao R-P, Tang J, 2004. Dysregulation of HSG triggers vascular proliferative disorders. Nat. Cell Biol 6, 872–883. doi: 10.1038/ncb1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Gong Q, Stice JP, Knowlton AA, 2009. Mitochondrial OPA1, apoptosis, and heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res 84, 91–99. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Liu T, Tran A, Lu X, Tomilov AA, Davies V, Cortopassi G, Chiamvimonvat N, Bers DM, Votruba M, Knowlton AA, 2012. OPA1 mutation and late-onset cardiomyopathy: mitochondrial dysfunction and mtDNA instability. J Am Heart Assoc 1, e003012. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.003012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X-G, Chen L-H, Xu R-X, Zhang H-T, 2018. Effect evaluation of methylprednisolone plus mitochondrial division inhibitor-1 on spinal cord injury rats. Childs Nerv Syst 34, 1479–1487. doi: 10.1007/s00381-018-3792-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Dorn GW, 2013. PINK1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science 340, 471–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1231031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Liu Y, Dorn GW, 2011. Mitochondrial fusion is essential for organelle function and cardiac homeostasis. Circ Res 109, 1327–1331. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Li Y, Wang Y, Qian J, Ma H, Wang X, Jiang G, Liu M, An Y, Ma L, Kang L, Jia J, Yang C, Zhang G, Chen Y, Gao W, Fu M, Huang Z, Tang H, Zhu Y, Ge J, Gong H, Zou Y, 2018. Cardiomyocyte-Restricted Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 6 (LRP6) Deletion Leads to Lethal Dilated Cardiomyopathy Partly Through Drp1 Signaling. Theranostics 8, 627–643. doi: 10.7150/thno.22177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherok E, Xu S, Li S, Das S, Meltzer WA, Zalzman M, Wang C, Karbowski M, 2017. Novel regulatory roles of Mff and Drp1 in E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH5-dependent degradation of MiD49 and Mcl1 and control of mitochondrial dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell 28, 396–410. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-04-0208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho D-H, Nakamura T, Fang J, Cieplak P, Godzik A, Gu Z, Lipton SA, 2009. S-nitrosylation of Drp1 mediates beta-amyloid-related mitochondrial fission and neuronal injury. Science 324, 102–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1171091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun BY, Rizzo JF, 2016. Dominant optic atrophy: updates on the pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of the optic atrophy 1 mutation. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 27, 475–480. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Dal Zilio B, Scorrano L, 2004. OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 101, 15927–15932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407043101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinton RW, Francy CA, Ramachandran R, Qi X, Mears JA, 2016. Dynamin-related Protein 1 Oligomerization in Solution Impairs Functional Interactions with Membrane-anchored Mitochondrial Fission Factor. J Biol Chem 291, 478–492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.680025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Course MM, Xinnan Wang, 2016. Transporting mitochondria in neurons. F1000Res 5, 1735. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7864.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covill-Cooke C, Howden JH, Birsa N, Kittler JT, 2018. Ubiquitination at the mitochondria in neuronal health and disease. Neurochem. Int 117, 55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribbs JT, Strack S, 2007. Reversible phosphorylation of Drp1 by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and calcineurin regulates mitochondrial fission and cell death. EMBO Rep 8, 939–944. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas G, Weaver D, Hajnóczky G, 2018. Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Contactology: Structure and Signaling Functions. Trends Cell Biol 28, 523–540. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Tang X, Christian WV, Yoon Y, Tieu K, 2010. Perturbations in mitochondrial dynamics induced by human mutant PINK1 can be rescued by the mitochondrial division inhibitor mdivi-1. J Biol Chem 285, 11740–11752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies VJ, Hollins AJ, Piechota MJ, Yip W, Davies JR, White KE, Nicols PP, Boulton ME, Votruba M, 2007. Opa1 deficiency in a mouse model of autosomal dominant optic atrophy impairs mitochondrial morphology, optic nerve structure and visual function. Hum Mol Genet 16, 1307–1318. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brito OM, Scorrano L, 2008. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature 456, 605–610. doi: 10.1038/nature07534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton K, Mou Y, Xu C-C, Shah D, Chang J, Blackstone C, Li X-J, 2018. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics underlie axonal defects in hereditary spastic paraplegias. Hum Mol Genet 27, 2517–2530. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detmer SA, Chan DC, 2007. Complementation between mouse Mfn1 and Mfn2 protects mitochondrial fusion defects caused by CMT2A disease mutations. J. Cell Biol 176, 405–414. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine MJ, Kittler JT, 2018. Mitochondria at the neuronal presynapse in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 19, 63–80. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disatnik M-H, Ferreira JCB, Campos JC, Gomes KS, Dourado PMM, Qi X, Mochly-Rosen D, 2013. Acute inhibition of excessive mitochondrial fission after myocardial infarction prevents long-term cardiac dysfunction. J Am Heart Assoc 2, e000461. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn GW, Clark CF, Eschenbacher WH, Kang M-Y, Engelhard JT, Warner SJ, Matkovich SJ, Jowdy CC, 2011. MARF and Opa1 control mitochondrial and cardiac function in Drosophila. Circ Res 108, 12–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.236745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn GW, Vega RB, Kelly DP, 2015. Mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics in the developing and diseased heart. Genes Dev. 29, 1981–1991. doi: 10.1101/gad.269894.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Wen J, Wang Y, Karmaus PWF, Khatamian A, Tan H, Li Y, Guy C, Nguyen T-LM, Dhungana Y, Neale G, Peng J, Yu J, Chi H, 2018. Hippo/Mst signalling couples metabolic state and immune function of CD8α+ dendritic cells. Nature 558, 141–145. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0177-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehses S, Raschke I, Mancuso G, Bernacchia A, Geimer S, Tondera D, Martinou J-C, Westermann B, Rugarli EI, Langer T, 2009. Regulation of OPA1 processing and mitochondrial fusion by m-AAA protease isoenzymes and OMA1. J. Cell Biol 187, 1023–1036. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner V, Picard M, Hajnóczky G, 2018. Mitochondrial dynamics in adaptive and maladaptive cellular stress responses. Nat. Cell Biol 20, 755–765. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0133-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]