Abstract

Background

Laying hens supplemented with betaine demonstrate activated adrenal steroidogenesis and deposit higher corticosterone (CORT) in the egg yolk. Here we further investigate the effect of maternal betaine on the plasma CORT concentration and adrenal expression of steroidogenic genes in offspring pullets.

Results

Maternal betaine significantly reduced (P < 0.05) plasma CORT concentration and the adrenal expression of vimentin that is involved in trafficking cholesterol to the mitochondria for utilization in offspring pullets. Concurrently, voltage-dependent anion channel 1 and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, the two mitochondrial proteins involved in cholesterol influx, were both down-regulated at mRNA and protein levels. However, enzymes responsible for steroid syntheses, such as cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily A member 1 and cytochrome P450 family 21 subfamily A member 2, were significantly (P < 0.05) up-regulated at mRNA or protein levels in the adrenal gland of pullets derived from betaine-supplemented hens. Furthermore, expression of transcription factors, such as steroidogenic factor-1, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 and cAMP response element-binding protein, was significantly (P < 0.05) enhanced, together with their downstream target genes, such as 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, LDL receptor and sterol regulatory element-binding protein cleavage-activating protein. The promoter regions of most steroidogenic genes were significantly (P < 0.05) hypomethylated, although methyl transfer enzymes, such as AHCYL, GNMT1 and BHMT were up-regulated.

Conclusions

These results indicate that the reduced plasma CORT in betaine-supplemented offspring pullets is linked to suppressed cholesterol trafficking into the mitochondria, despite the activation of cholesterol and corticosteroid synthetic genes associated with promoter hypomethylation.

Keywords: Adrenal gland, Chicken, Cholesterol, Corticosterone, Maternal betaine, Steroidogenesis

Background

Corticosterone (CORT) synthesis in the adrenal gland requires a continuous supply of cholesterol that is delivered to mitochondria as a substrate for steroidogenesis [1]. Mobilization of cholesterol from the cytoplasm into mitochondria is the rate-limiting step in steroidogenesis, which involves the actions of intermediate cytoskeleton filament proteins [2], such as vimentin (VIM) [3]. The role of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) in shuttling cholesterol to the inner mitochondria membrane (IMM) has been well documented [4–8]. Also, the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) not only regulates StAR activity at the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) [9, 10], but also interacts with StAR to assist the transfer of cholesterol into the IMM [11]. However, it is unknown whether feeding betaine to laying hens may affect the adrenal steroidogenesis in their progeny by targeting cholesterol shuttling machinery.

Steroidogenesis necessitates complex inter-communication among several subcellular compartments which demand regulation of cholesterol synthesis [12]. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBP) drive the expression of genes involved in cholesterol synthesis [13]. In mammals, SREBP2 is more involved in cholesterol synthesis, while SREBP-1a is involved in both fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis [14]. In chickens, SREBP1 is highly homologous to SREBP1a in mammals [15]. However, less information is available regarding the role of SREBP1 in cholesterol synthesis in the adrenal glands of chickens.

Betaine is a feed additive to improve the growth performance in livestock [16] and to attenuate heat stress in poultry [17]. A number of studies have implicated a close relationship between betaine and glucocorticoids to coordinate the body functions for the recovery from stress. For instance, athletes subjected to intense exercise were detected increased betaine and decreased cortisol levels in the blood [18]. In another study, dietary betaine supplementation in sows during gestation reduced plasma cortisol level in neonatal piglets [19]. Also, dietary betaine alleviates heat stress in poultry by decreasing the plasma CORT level [20]. Nevertheless, the effect of betaine on plasma CORT level in the chicken is not consistent, which depends on the level and timing of betaine administration as well as the physiological status of the birds. Previously, we reported that dietary betaine supplementation to laying hens led to increased CORT deposition in the egg yolk [21]. Therefore, questions arise whether maternal betaine supplementation affects the adrenal CORT production and plasma CORT concentrations in chicken offspring later in life.

Betaine is an essential component of the methionine cycle [22] and can affect intracellular metabolism via modulating DNA methylation [23]. We reported previously that in ovo injection of betaine affects hepatic cholesterol metabolism in newly hatched chicks through epigenetic modifications [24]. However, it remains unknown whether maternal betaine would affect adrenal steroidogenic genes through epigenetic modifications in offspring chickens.

Therefore, here we sought to investigate the effect of maternal betaine supplementation on the adrenal expression of cholesterol trafficking genes in association with alterations in plasma corticosterone concentration; and to elucidate the mechanisms by determining the expression of methyl transfer genes and DNA methylation status on the promoter of relevant genes in offspring pullets.

Methods

Experimental design

One hundred and twenty Rugao yellow-feathered laying hens (1.4 ± 0.10 kg, mean ± SEM) were obtained from Poultry Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Yangzhou, China. Hens were randomly allocated into control (CON) and betaine-supplemented (BET) groups at 38 weeks of age, fed basal and betaine-supplemented diets, respectively, for 28 d. Betaine hydrochloride (98% purity, Skystone Feed Co., Ltd, Jiangsu, China) was added to the basal diet at the level of 0.5%. Laying hens were artificially inseminated at the 18th and 24th day post dietary treatment. Fertilized eggs were collected from 25th to 28th day post dietary treatment (200 eggs from each group) and incubated under standard conditions. Newly hatched chicks were raised following the standard established by the breeder. All the chicks were fed the same diet until 56 days of age when 15 pullets in each group were randomly selected and killed by rapid decapitation. The detailed procedure for rearing and slaughtering has been described in a previous publication [25]. Blood samples were taken from the jugular vein, and plasma was separated and stored at − 20 °C. Adrenal glands were dissected and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for further analyses.

Determination of plasma total cholesterol

Total cholesterol concentration in the plasma was determined with an automatic biochemical analyzer (Beckman coulter, AU2700), using a commercial kit purchased from Maccura Biology Co., Ltd. (ECH0103152, Chengdu, China). The intra-assay coefficient of variation was less than 3.0%.

Plasma corticosterone assay

Corticosterone concentration in the plasma was measured with a commercial Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) kit (No.ADI-900-097, Enzo, USA). The detection limit was 26.99 pg/mL and the intra-assay coefficient of variation was 8%.

Total RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from 20 mg adrenal samples using 1 mL of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and 2 μg of total RNA was subjected to RT-PCR as previously described [21]. The technical variations were normalized using beta-actin as an internal control. Samples were run in duplicates. Primers for real-time PCR (Table 1) were synthesized by Genewiz (Suzhou, China). Data were analyzed using the method of 2−△△CT [26], and the results are presented as the fold change relative to the average value of the control group.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequences of specific primers used for real-time PCR

| Target genes | GenBank accession | Primer sequences (5′ to 3′) | PCR products, bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| StAR | NM_204686.2 | F:ATGGCATCCAAGGAGTGA | 103 |

| R: GGGAGACAGAAGGGAACAG | |||

| CYP11A1 | NM_001001756.1 | F: AGCACTTCAAGGGACTGAGC | 147 |

| R:ACTTGGTCCCAACTTCCACC | |||

| 3BHSD2 | XM_417988.5 | F: CTGGAAGAAGATGAGGCGCT | 249 |

| R: ACCTGTCACGTTGACTTCCC | |||

| CYP21A2 | >NM_001099358.1 | F: CTTTGAGGCGTTCACGTTCC | 169 |

| R: CTGGGACTCCACAAAGGCAT | |||

| CYP19A1 | NM_001364699.1 | F: CATGCACCCAATAGAAAGGCA | 130 |

| R: GCATTTCTTAAAGTGACTGCAAAC | |||

| CYP17A1 | NM_001001901.2 | F: TCTGCTCCCTCTGCTTCAA | 250 |

| R: AGGTCCCTCACAGTGTCCC | |||

| SF-1 | XM_015279334.1 | F: TCTTCCTGAATTTCCCTT | 151 |

| R: TGAACATCCCATCTAGTGA | |||

| CREB | XM_015294628.2 | F: GTCAGACACACCAGAGCCTT | 128 |

| R: CATTCCTGCTCCCCTTCCTC | |||

| BHMT | XM_414685.3 | F: CGAGTGGGACGGCTTCTT | 144 |

| R: AGGCGATAGGTGTCAGGGA | |||

| AHCYL1 | NM_001030913.1 | F:TGGTGTTGTTGGGGGAGAT | 227 |

| R:CCCCATCAATACTCATCCAAC | |||

| DNMT1 | NM_206952.1 | F:TGATAYGTTGGATGAGTATTGATGG | 264 |

| R: AAAAAAACTCTCACTCAACTCCAC | |||

| GNMT1 | XM_015283546.1 | F: GGAGGAGGGCTTCCAAGTGA | 140 |

| R: GCTCCAGCGTCAGCCAGTT | |||

| VIM | AH002482.2 | F: CTTTGCCCAGTGCTGTAGTC | 171 |

| R: AAACACGGGCTGTCAGTCA | |||

| VDAC1 | NM_001033869.2 | F: GAACAGGGACGGGGACAG | 136 |

| R: CAGACTTGCCCAGATCAGCA |

Total protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from 15 mg frozen adrenal samples, as previously described [24]. BCA Protein Assay kit (No. 23225, Thermo Scientific) was used to measure protein concentrations following manufacturer’s instructions. Fifty micrograms of protein were used for electrophoresis on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. Western blot analysis was performed following the protocols provided by the manufacturers. Tublin-β (AP0064, Bioworld, USA, diluted 1:5,000) was used as an internal reference. VersaDoc 4000MP system (Bio-Rad, USA) was employed to capture the images and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, USA) was used to analyze the band density.

Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) analysis

MeDIP analysis was executed according to a previous publication [27]. A small aliquot of MeDIP DNA and control input DNA was used to amplify the proximal promoter sequence of chicken VIM, VDAC1, StAR, CYP11A1, CYP21A2, SF-1, CREB and SREBP1 genes by RT-PCR with specific primers listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Nucleotide sequences of primers used for MeDIP

| Target genes | Primer sequences (5′ to 3′) | PCR products, bp |

|---|---|---|

| StAR | ||

| Segment 1 | F: CAGGGACACCTCGGTTCTTC | 177 |

| R: GCTGTTATCCCAATGGAGCG | ||

| Segment 2 | F: CTCGGGGTCTTTCATTGCCA | 129 |

| R: CAGGGAGCAGGCGATAAGAT | ||

| Segment3 | F: GGCGGTTTCTGTTCAGAGGT | 160 |

| R:: CAGAGCAACACCCCAAACAC | ||

| Segment 4 | F: GGCGGTTTCTGTTCAGAGGT | 196 |

| RACAGAGCAACACCCCAAACAC | ||

| CYP11A1 | ||

| Segment 1 | F: TAAGGGCCGTGTTTTGGAGG | 194 |

| R: TGGGGACTCAGCAGATTTCG | ||

| Segment 2 | F: AACTGACAGCGTAATGCCCA | 164 |

| R: AAAGAGGGGGTTGGAAACGG | ||

| Segment3 | F: CAGGGTATGGGTTGCAGGTT | 116 |

| R: GTGGAAAACCCCCATCGTCT | ||

| CYP21A2 | F: CTCAACGTGAGATCTGGGGG | 148 |

| R: TTGAAAGGTCCAGTTGGGGG | ||

| VIM | ||

| Segment 1 | F: GTGGGGACGCCGCTCTT | 181 |

| R: GGGTGCTGGACGTGATGTAG | ||

| Segment2 | F: GGGACGCCGCTCTTCTT | 110 |

| R: GAGGAGTTCTTGCTGCTGGT | ||

| SF-1 | ||

| Segment 1 | F: CATTTACCCCCGCAAACACC | 187 |

| F: CTCTAGCAGGTTCAAGGTCCC | ||

| Segment 2 | F: TATCGCCAAAGTCCTCACCG | 193 |

| R: CTCCATCCACGCGGCTTATC | ||

| VDAC1 | F: AAGTGATCTGCCTGTCTCGG | 144 |

| R: TTGAGGCTGGGAGCAAATGT | ||

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. The normality and homogeneity of variances were checked before using parametric analyses. When the data were not normally distributed, the log10 transformation was performed before statistical analysis. T-test for independent samples was performed for comparisons using SPSS 20.0 for windows. The differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

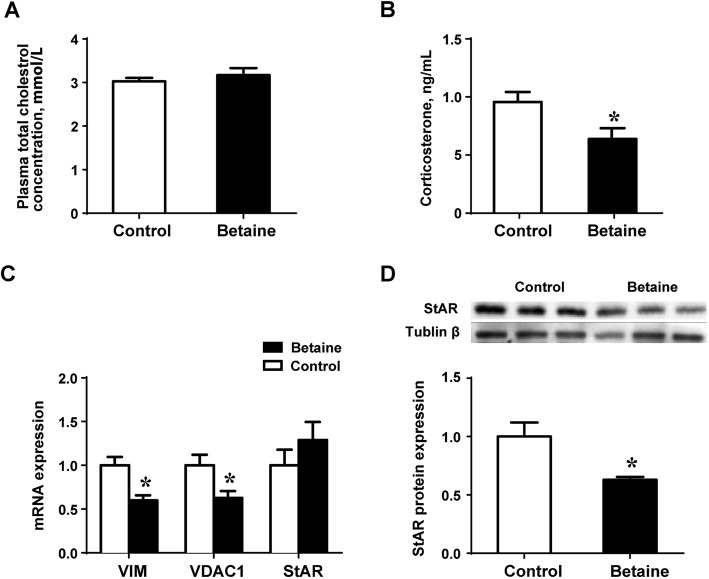

Plasma corticosterone, total cholesterol and adrenal expression of cholesterol trafficking genes

Maternal betaine did not affect plasma total cholesterol in the young pullets (Fig. 1a). However, plasma corticosterone concentration was significantly decreased (P < 0.05) in the betaine group, together with the mRNA abundance of VIM and VADC1 genes (Fig. 1b and c). StAR protein content was significantly (P < 0.05) down-regulated (Fig. 1d) in the adrenal glands of pullets derived from betaine-supplemented hens, although no difference was detected at the mRNA level.

Fig. 1.

Plasma corticosterone, total cholesterol and adrenal expression of cholesterol trafficking genes in pullets. a) Plasma total cholesterol; b) Plasma corticosterone c) mRNA abundance of genes involved in cholesterol trafficking d) StAR protein expression. Values are means ± SEM, *P < 0.05, compared with control for the mRNA (n = 7), for protein expression (n = 4)

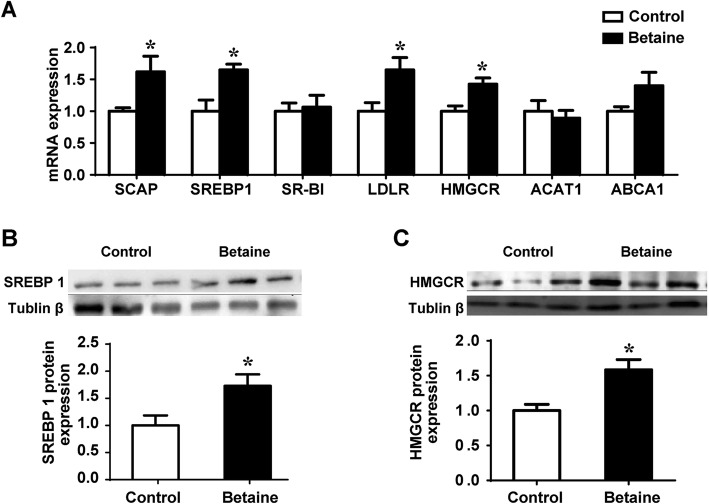

Adrenal expression of cholesterol metabolic genes

SCAP, the escort protein that engages SREBP in de novo cholesterol synthesis, and low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) that involved in cholesterol uptake, were both significantly (P < 0.05) up-regulated at mRNA level (Fig. 2a). Also, both SREBP1 and 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), the rate-limiting enzyme for cholesterol synthesis, were significantly (P < 0.05) increased at both mRNA (Fig. 2b) and protein levels (Fig. 2c) in the adrenal glands of pullets derived from betaine-supplemented hens.

Fig. 2.

Adrenal expression of cholesterol metabolic genes in pullets. a) Cholesterol biosynthetic genes mRNA expression; b) SREBP1 protein expression; c) HMGCR protein expression. Values are means ± SEM, *P < 0.05, compared with control for the mRNA (n = 7), for protein expression (n = 4)

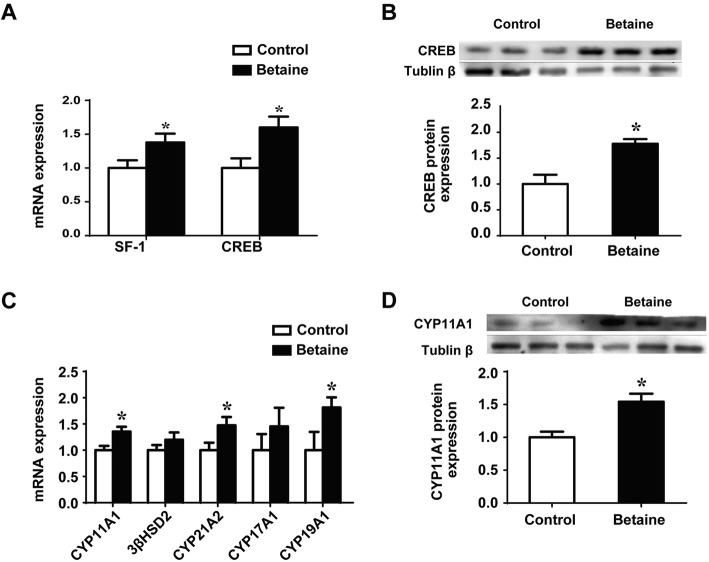

Adrenal expression of transcription factors and downstream corticosteroid biosynthetic enzymes

The adrenal expression of SF1 was significantly (P < 0.05) up-regulated at mRNA level, while that of CREB was significantly (P < 0.05) increased at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 3a and b) in pullets derived from betaine-supplemented hens. Additionally, both mRNA abundance (Fig. 3c) and protein content (Fig. 3d) of CYP11A1 were significantly (P < 0.05) increased in the betaine group. Concurrently, CYP21A2 and CYP19A1 mRNA abundances were also significantly elevated (P < 0.05), in comparison with their control counterparts (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Adrenal expression of transcription factors and downstream corticosteroid biosynthetic enzymes in pullets. a) SF-1 and CREB mRNA expression b) CREB protein expression; c) mRNA expression of corticosteroid biosynthesis enzymes; d) CYP11A1 protein expression. Values are means ± SEM, *P < 0.05, compared with control for the mRNA (n = 7), for protein expression (n = 4)

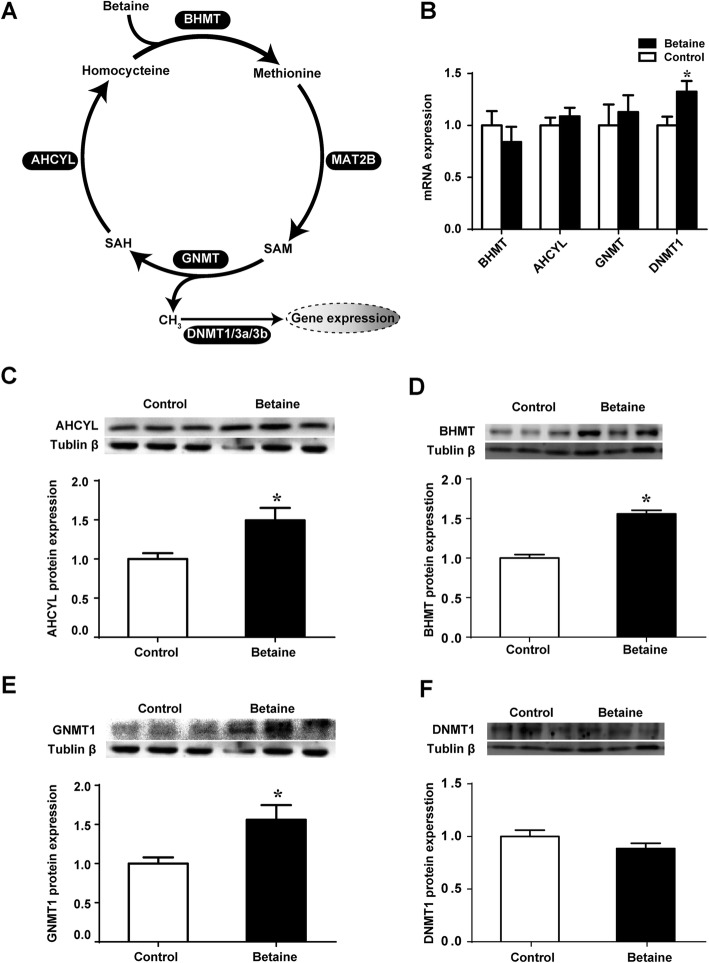

Adrenal expression of methionine metabolic genes

Enzymes involved in the methionine cycle are shown in the schematic diagram (Fig. 4a). No changes were detected for AHCYL, BHMT or GNMT at the level of mRNA (Fig. 4b), but all three of them were significantly up-regulated (P < 0.05) at the protein levels (Fig. 4c, d and e). Interestingly, DNMT1 mRNA was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the betaine group compared with the control group, but no alterations were detected at the protein level (Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4.

Adrenal expression of methionine metabolic genes in pullets. a) Schematic diagram of methionine cycle; b) Adrenal expression of key enzymes involved in methionine metabolic cycle at the mRNA; c) AHCYL protein expression; d) BHMT protein expression; e) GNMT1 protein expression; f) DNMT1 protein expression. Values are means ± SEM, *P < 0.05, compared with control. mRNA (n = 7), for protein expression (n = 4)

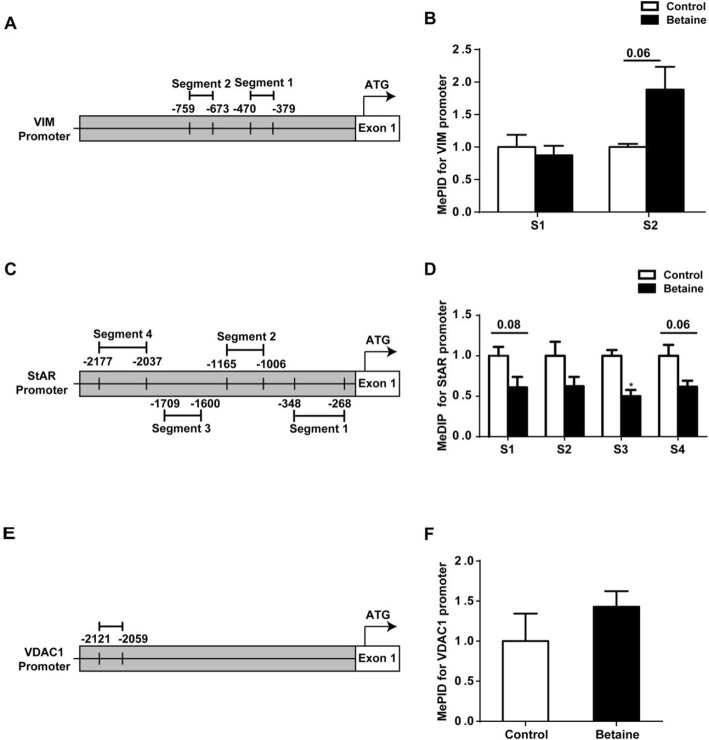

DNA methylation of cholesterol trafficking gene promoters

Different segments (S) of the promoter sequences of chicken VIM (Fig. 5a), StAR (Fig. 5c), and VDAC1 (Fig. 5e) were analyzed with MeDIP-PCR technique. Maternal betaine tended (P = 0.06) to increase DNA methylation level on the S2 of VIM gene promoter (Fig. 5b), while S3 on StAR gene promoter was significantly (P < 0.05) hypomethylated in betaine group, together with S1 (P = 0.08) and S4 (P = 0.06) that showed a tendency of hypomethylation (Fig. 5c). No alteration was detected for the methylation status on VDAC1 gene (Fig. 5f).

Fig. 5.

DNA methylation of cholesterol trafficking gene promoters in adrenal glands of pullets. a) Schematic diagram showing the amplified segments (S) on the promoter sequence of VIM. b) DNA methylation status on the promoter of VIM; c) Schematic diagram showing the amplified StAR segments (S); d) DNA methylation status on the promoter of StAR; e) Schematic diagram showing the amplified VDAC1 (S); f) DNA methylation status on the promoter of VDAC1. Values are means ± SEM, *P < 0.05, compared with control (n = 3)

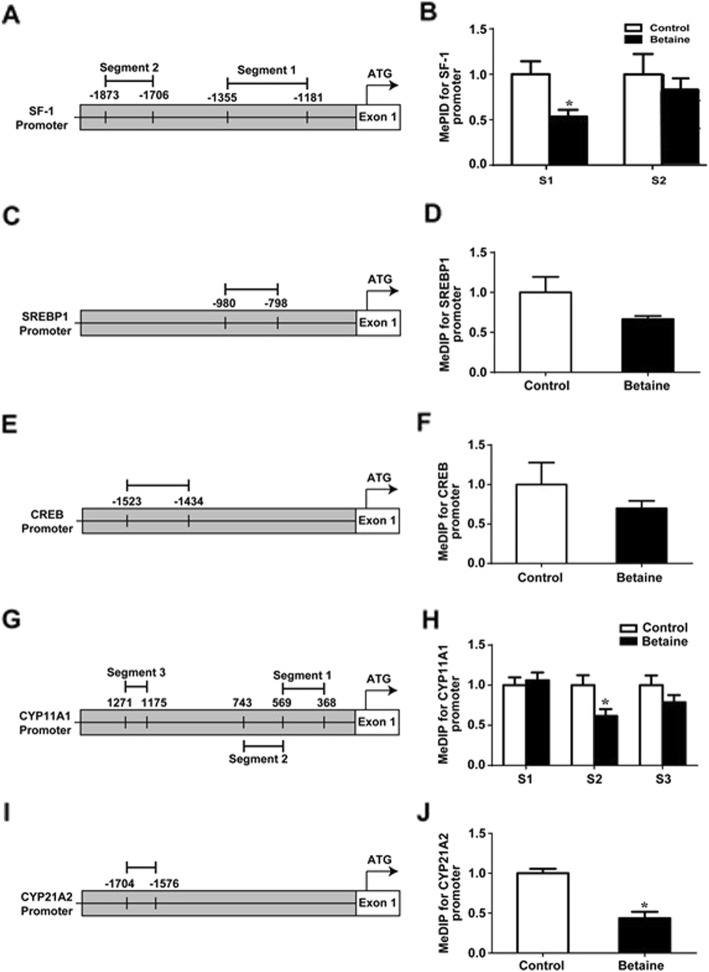

DNA methylation of transcription factors and steroidogenic genes promoters

Moreover, the promoter sequences of genes coding for relevant transcription factors, including SF-1 (Fig. 6a), SREBP1 (Fig. 6c) and CREB (Fig. 6e), as well as steroidogenic enzymes, such as CYP11A1 (Fig. 6g) and CYP21A2 (Fig. 6i), were also analyzed. S1 of the SF-1 gene promoter showed a significant (P < 0.05) hypomethylation in betaine group (Fig. 6b), while no differences were detected for either SREBP1 or CREB gene promoters (Fig. 6d and f). S2 of the CYP11A1 promoter (Fig. 6h), together with CYP21A2 gene promoter sequence (Fig. 6j), was significantly (P < 0.05) hypomethylated in the adrenal gland of pullets derived from betaine-exposed hens.

Fig. 6.

DNA methylation of transcript factors and steroidogenic genes promoters in adrenal glands of pullets. a) Schematic diagram showing the amplified segments (S) on the promoter sequence of SF-1. b) DNA methylation status on the promoter of SF-1; c) Schematic diagram showing the amplified CREB; d) DNA methylation status on the promoter of CREB. e) Schematic diagram showing the amplified segments (S) on the promoter sequence of SREBP1. f) DNA methylation status on the promoter of SREBP1; g) Schematic diagram showing the amplified CYP11A1; h) DNA methylation status on the promoter of CYP11A1.; i) Schematic diagram showing the amplified CYPA2(S); j) DNA methylation status on the promoter of CYP21A2. Values are means ± SEM, *P < 0.05, compared with control (n = 3)

Discussion

Developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) has attracted attention in the field of biomedical research. Several studies demonstrated the effect of maternal nutrition during pregnancy on serum CORT level in rat offspring. For example, feeding dams with a protein-restricted diet led to increased plasma CORT level in rat offspring [28]. Also, maternal high-fructose consumption increases plasma CORT concentration in adult rat offspring [29]. The adverse effects of maternal malnutrition on offspring are considered to be mediated, at least partly, by dysregulated CORT production.

In this study, maternal betaine reduced plasma CORT concentration in offspring chicken, which was associated with suppressed expression of cholesterol trafficking genes, such as VIM, StAR and VDAC1, in adrenal glands of the pullets. Shen et al. [30] found a marked reduction of plasma CORT and progesterone levels in VIM null mice. Likewise, shuttling cholesterol into the mitochondria requires the interplay of VDAC with StAR [19]. The abundant presence of VDAC on cholesterol ester (CE)-enriched LDs points to the role of VDAC in promoting CE mobilization into the mitochondria [31]. Also, CORT production was depressed in StAR null mice [32]. In this study, no alteration was detected in plasma total cholesterol concentration, and the adrenal content of cholesterol was not measured due to limited sample size. However, the consistent suppression of all the three cholesterol trafficking genes led to an assumption that maternal betaine decreased the plasma CORT concentration in offspring pullets via inhibiting the process of cholesterol shuttling to mitochondria for CORT biosynthesis.

SREBP1 serves as a cholesterol sensor to activate or suppress the cholesterol biosynthesis to maintain the intracellular cholesterol homeostasis [33]. Shortage of intracellular cholesterol will activate the cholesterol synthesis loop by LDLR and HMGCR. Conversely, when intracellular cholesterol concentrations are high, this process will be inhibited [34]. In this study, the SREBP1-mediated cholesterol feedback machinery was activated in the adrenal gland of pullets exposed prenatally to betaine. Both SCAP and SREBP1, alongside its downstream HMGCR and LDLR, were up-regulated. SREBPs triggering requires SCAP and many transcription factors, such as CREB and SF-1 [10, 35]. In this study, maternal betaine also significantly up-regulated SF1 at the mRNA level and CREB at both mRNA and protein levels. In accordance with these findings, the downstream enzymes responsible for steroidogeneses such as cytochrome P450 family members, including CYP11A1, CYP21A2 and CYP19A1, were all significantly up-regulated in the betaine group. Together, our results indicate that the increase of SREBP1-mediated cholesterol biosynthesis and SF-1-activated steroidogenesis in the adrenal gland of young pullets from the betaine group may represent a compensatory adaptation to the decrease in plasma CORT concentration.

DNA methylation is recognized as a fundamental mechanism in the regulation of steroidogenic genes [36]. For instance, prenatal caffeine exposure decreased SF-1 mRNA expression in association with DNA hypermethylation in the SF1 gene promoter [37]. DNMTs are responsible for DNA methylation required for normal cellular metabolism [38]. In this study, maternal betaine enhanced the expression of the methionine cycle and methyl transfer enzymes such as GNMT1, AHCYL1 and DNMT1. Up-regulation of SF1, CYP11A1 and CYP21A2 genes coincided with hypomethylation of their promoters. However, a clear link between mRNA expression and promoter DNA methylation was missing for cholesterol trafficking genes. Further investigations are required to unravel the mechanisms by which maternal betaine suppresses the expression of cholesterol trafficking genes in adrenal glands of offspring pullets.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that maternal betaine decreases plasma CORT level with suppressed expression of cholesterol trafficking genes in the adrenal gland of offspring chickens. The lower basal plasma CORT concentration may allow pullets better coping with stress during the laying period. However, future studies are required to evaluate the long-term effect of maternal betaine on the laying performance of their female progeny.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACTH

Adrenocorticotrophic hormone

- AHCYL1

Adenosylhomocysteinase-like 1

- BHMT

Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase

- CREB

CAMP response element-binding protein

- CYP

Cytochrome P450

- DNMTS

DNA methyltransferases

- GNMT

Glycine N-methyltransferase

- HPA

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- HSD

Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases

- IMM

Inner mitochondrial membrane

- MeDIP

Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation

- OMM

Outer mitochondrial membrane

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SF-1

Steroidogenic factor-1

- SREBPS

Sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- StAR

Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- VDAC1

Voltage-dependent anion channel 1

- VIM

Vimentin

Authors’ contributions

HA, performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. YH, NO, ZH performed the animal experiment, recorded and analysed the phenotypic data and took the samples. AI analysed the data. RZ contributed to experimental concepts and design, provided scientific direction, analysed and interpreted the results, and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31672512), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KYZ201212), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD) and Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Centre of Meat Production and Processing, Quality and Safety Control.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Animal Ethics Committee of Nanjing Agricultural University approved the experimental protocol, with project number 31672512. The sampling procedures complied with the “Guidelines on Ethical Treatment of Experimental Animals” (2006) No. 398 set by the Ministry of Science and Technology, China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Halima Abobaker, Email: halima450@hotmail.com.

Yun Hu, Email: 821517588@qq.com.

Nagmeldin A. Omer, Email: ngmo410@hotmail.com

Zhen Hou, Email: 295273571@qq.com.

Abdulrahman A. Idriss, Email: abdodr@gmail.com

Ruqian Zhao, Phone: 00862584395047, Email: zhao.ruqian@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Hu J, Zhang Z, Shen W-J, Azhar S. Cellular cholesterol delivery, intracellular processing and utilization for biosynthesis of steroid hormones. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2010;7(1):47. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sewer MB, Li D. Regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis by the cytoskeleton. Lipids. 2008;43(12)):1109. doi: 10.1007/s11745-008-3221-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraemer FB, Khor VK, Shen W-J, Azhar S. Cholesterol ester droplets and steroidogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinal. 2013;371(1–2):15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stocco DM, Clark BJ. Role of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) in steroidogenesis. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;51(3):197–205. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stocco DM, Clark BJ, Reinhart AJ, Williams SC, Dyson M, Dassi B, et al. Elements involved in the regulation of the StAR gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;177(1):55–59. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsujishita Y, Hurley JH. Structure and lipid transport mechanism of a StAR-related domain. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(5):408–414. doi: 10.1038/75192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Liu Z, Eimerl S, Timberg R, Weiss AM, Orly J, et al. Effect of truncated forms of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein on intramitochondrial cholesterol transfer. Endocrinology. 1998;139(9):3903–3912. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.9.6204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajapaksha M, Kaur J, Bose M, Whittal RM, Bose HS. Cholesterol-mediated conformational changes in the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein are essential for steroidogenesis. Biochemistry. 2013;52(41):7242–7253. doi: 10.1021/bi401125v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad M, Kaur J, Pawlak KJ, Bose M, Whittal RM, Bose HS. Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM) regulates steroidogenic activity via steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR)-voltage-dependent anion channel 2 (VDAC2) interaction. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(5):2604–2616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.605808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajapaksha M, Kaur J, Prasad M, Pawlak KJ, Marshall B, Perry EW, et al. Outer mitochondrial translocase, Tom22, is crucial for inner mitochondrial steroidogenic regulation in adrenal and gonadal tissues. Mol Cell Biol. 2016;36(6):1032–1047. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01107-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bose M, Whittal RM, Miller WL, Bose HS. Steroidogenic activity of StAR requires contact with mitochondrial VDAC1 and phosphate carrier protein. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(14):8837–8845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709221200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papadopoulos V, Miller WL. Role of mitochondria in steroidogenesis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(6):771–790. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tontonoz P, Kim J, Graves R, Spiegelman B. ADD1: a novel helix-loop-helix transcription factor associated with adipocyte determination and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(8):4753–4759. doi: 10.1128/MCB.13.8.4753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eberle D, Hegarty B, Bossard P, Ferre P, Foufelle F. SREBP transcription factors: master regulators of lipid homeostasis. Biochimie. 2004;86(11):839–848. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Hillgartner FB. Starvation and feeding a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet regulate the expression sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 in chickens. J Nutr. 2004;134(9):2205–2210. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eklund M, Bauer E, Wamatu J, Mosenthin R. Potential nutritional and physiological functions of betaine in livestock. Nutr Res Rev. 2005;18(1):31–48. doi: 10.1079/NRR200493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saeed M, Babazadeh D, Naveed M, Arain MA, Hassan FU, Chao S. Reconsidering betaine as a natural anti-heat stress agent in poultry industry. A review Trop Anim Health Prod. 2017;49(7):1329–1338. doi: 10.1007/s11250-017-1355-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apicella JM, Lee EC, Bailey BL, Saenz C, Anderson JM, Craig SA, et al. Betaine supplementation enhances anabolic endocrine and Akt signaling in response to acute bouts of exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113(3):793–802. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai D, Wang J, Jia Y, Liu H, Yuan M, Dong H, Zhao R. Gestational dietary betaine supplementation suppresses hepatic expression of lipogenic genes in neonatal piglets through epigenetic and glucocorticoid receptor-dependent mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1861(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratriyanto A, Mosenthin R. Osmoregulatory function of betaine in alleviating heat stress in poultry. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2018;102(6):1634–1650. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abobaker H, Hu Y, Hou Z, Sun Q, Idriss AA, Omer NA, et al. Dietary betaine supplementation increases adrenal expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein and yolk deposition of corticosterone in laying hens. Poult Sci. 2017;96(12):4389–4398. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lever M, Slow S. The clinical significance of betaine, an osmolyte with a key role in methyl group metabolism. Clin Biochem. 2010;43(9):732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinclair KD, Allegrucci C, Singh R, Gardner DS, Sebastian S, Bispham J, et al. DNA methylation, insulin resistance, and blood pressure in offspring determined by maternal periconceptional B vitamin and methionine status. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104(49):19351–19356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707258104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Y, Sun Q, Li X, Wang M, Cai D, Li X, Zhao R. In ovo injection of betaine affects hepatic cholesterol metabolism through epigenetic gene regulation in newly hatched chicks. PloS One. 2015;10(4):e0122643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Hou Z, Sun Q, Hu Y, Yang S, Zong Y, Zhao R. Maternal betaine administration modulates hepatic type 1 iodothyronine deiodinase (Dio1) expression in chicken offspring through epigenetic modifications. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;218:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Y, Sun Q, Liu J, Jia Y, Cai D, Idriss AA, et al. In ovo injection of betaine alleviates corticosterone-induced fatty liver in chickens through epigenetic modifications. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40251. doi: 10.1038/srep40251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fagundes A, Moura E, Passos M, Oliveira E, Toste F, Bonomo I, Trevenzoli I, et al. Maternal low-protein diet during lactation programmes body composition and glucose homeostasis in the adult rat offspring. Br J Nutr. 2007;98(5):922–928. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507750924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munetsuna E, Yamada H, Yamazaki M, Ando Y, Mizuno G, Hattori Y, et al. Maternal high-fructose intake increases circulating corticosterone levels via decreased adrenal corticosterone clearance in adult offspring. J Nutr Biochem. 2019;67:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen W-J, Zaidi SK, Patel S, Cortez Y, Ueno M, Azhar R, et al. Ablation of vimentin results in defective steroidogenesis. Endocrinology. 2012;153(7):3249–3257. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khor VK, Ahrends R, Lin Y, Shen W-J, Adams CM, Roseman AN, et al. The proteome of cholesteryl-ester-enriched versus triacylglycerol-enriched lipid droplets. PloS One. 2014;9(8):e105047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stocco DM, Zhao AH, Tu LN, Morohaku K, Selvaraj V. A brief history of the search for the protein(s) involved in the acute regulation of steroidogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;441:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The SREBP pathway regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 1997;89(3):331–340. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai D, Yuan M, Liu H, Pan S, Ma W, Hong J, et al. Maternal betaine supplementation throughout gestation and lactation modifies hepatic cholesterol metabolic genes in weaning piglets via AMPK/LXR-mediated pathway and histone modification. Nutrients. 2016;8(10):646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Brown AJ, Sun L, Feramisco JD, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Cholesterol addition to ER membranes alters conformation of SCAP, the SREBP escort protein that regulates cholesterol metabolism. Mol Cell. 2002;10(2):237–245. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez-Arguelles DB, Papadopoulos V. Epigenetic regulation of the expression of genes involved in steroid hormone biosynthesis and action. Steroids. 2010;75(7):467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ping J, Wang J-F, Liu L, Yan Y-E, Liu F, Lei Y-Y, Wang H. Prenatal caffeine ingestion induces aberrant DNA methylation and histone acetylation of steroidogenic factor 1 and inhibits fetal adrenal steroidogenesis. Toxicology. 2014;321:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen T, Li E. Establishment and maintenance of DNA methylation patterns in mammals. In. DNA methylation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;301:179–201. doi: 10.1007/3-540-31390-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author upon request.